Search form

Thinking lab, professor woo-kyoung ahn.

- Publications

- Joining The Lab

Welcome to the Thinking Lab at Yale University!

The Thinking Lab is directed by Woo-kyoung Ahn, Professor of Psychology, Yale University. We are interested in any topics related to thinking, including causal learning and reasoning, and concepts and categorization. We study not only basic issues, but also applied issues, such as how different kinds of causal explanations for mental disorders affect how people think about mental disorders. Please visit our Research page to learn more about recent projects.

Announcement

- Thinking 101: How to reason better to live better is out. Click HERE for more information about the author and the book.

- Professor Ahn is currently accepting new graduate students. If you are interested in joining our lab as a graduate student, please click HERE .

Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

- Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Chapter 4: increasing critical thinking and motivation.

Different Perspectives

Think for a moment about how you got here. Presumably you like doing what you do; you were probably naturally better at it and more interested in it than anything else you studied in college. You might think of “Yale” almost exclusively as the department in which you study. You probably enjoy spending long hours alone, reading and writing about your subject, or carrying out your bench work. Maybe you’re one of those people who are incapable of discussing anything other than dissertation topics. And that’s all fine… for graduate school and graduate students. When you enter the undergraduate classroom, however, you need to keep the bigger picture in mind.

For undergraduates, Yale is a smorgasbord of opportunities and experiences (only a fraction of which are academic in nature). Undergraduates fill their plates from the chafing dishes of macroeconomics, poetry, organic chemistry, Italian, field hockey, and improvisational comedy. As a graduate student, you’re apt to think that your field is the tastiest dish on the buffet—it’s the most interesting and the most important. As a result, you’re likely to think about—and, consequently, teach—your subject in the way you first encountered it.

If your teaching philosophy is “There is one tried and true way to learn this material, and it is the best way,” then your teaching is laid out for you. You are carrying on a tradition. However, if you are willing to consider that there might be other ways to teach the subject, and other (possibly better) ways for students to learn it—if, in other words, you are open to experimentation—then you may want to consider the strategies presented in this section.

All of the strategies described here have one thing in common: they move the focus of attention away from the teacher to the student. Rather than focusing on what you’ll say in class, you’ll have to think more deeply about what your students will do and learn in class.

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

Associates in teaching program.

The competitive Associates in Teaching (AT) program, offered in collaboration between the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and the Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, allows Ph.D. students to expand their teaching experiences and responsibilities in partnership with a faculty member.

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

The Center for Teaching and Learning routinely assists members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Open Yale Courses

"To understand the structure of the human soul we must understand the structure of society; to understand the structure of society we must understand the structure of the human soul."

"To construct soaring vaults out of concrete, to face them with brick, to create windows large enough to dematerialize the wall - to do that at this kind of scale is an incredible architectural feat."

"In our collective cultural consciousness, whether we like him or not, we tend to think of John Milton as powerful."

"The moral dilemma is to prevent big, bad things from happening, and that takes a sort of entrepreneurship and big thinking to manage."

"Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Faulkner are the iconic figures of American Literature."

Open Yale Courses provides free and open access to a selection of introductory courses taught by distinguished teachers and scholars at Yale University. The aim of the project is to expand access to educational materials for all who wish to learn.

- All lectures were recorded in the Yale College classroom and are available in video, audio, and text transcript formats

- Registration is not required

- No course credit, degree, or certificate is available through the Open Yale Courses website. However, courses for Yale College credit are offered online through Yale Summer Online including OYC professors John Rogers and Craig Wright."

A Welcome From Diana E. E. Kleiner Founding Director and Principal Investigator We welcome you to explore Open Yale Courses where you can discover a wide range of timely and timeless topics taught by Yale professors, each with a unique perspective and an individual interpretation of a particular field of study. We hope the lectures and other course materials, which reflect the values of a Yale liberal arts education, inspire your own critical thinking and creative imagination. We greatly appreciate your enthusiastic response to this initiative and hope you will stay in touch!

Jump to content

- Recognition

- Directories

- Campus Services

- Financial Management

- Integrity and Ethical Conduct

- Learn and Grow

- Manager Toolkit

- Staff Resources

- Technology at Yale

- University Policies, Procedures, Forms, and Guides

- Office of Research Administration

- Office of Sponsored Projects

- Human Research Protection Program

- Animal Research Support

- Conflict of Interest Office

- Export Controls

- Office of Research Compliance

- Faculty Research Management Services

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Public Safety

Developing Soft Skills

Soft skills are among the most coveted skills sought by hiring managers. These are easily transferrable skills and are not necessarily associated to a specific job. Soft skills revolve around personal relationships, character, and attitude. By nurturing these interpersonal attributes, you will build stronger relationships and increase your work performance.

Please review the behavioral attributes for each soft skill below, then access the learning module in LinkedIn Learning to begin developing your skills.

Search form

Bias on the brain: a yale psychologist examines common ‘thinking problems’.

Woo-kyoung Ahn (Credit: Studio DUDA Photography)

The sometimes counterintuitive ways that our brains work can raise big questions. Why is it that we procrastinate, dragging our feet when we know we will regret it later? Why are misunderstandings and miscommunications so common? And why do people often turn a blind eye to evidence that contradicts their beliefs?

For Yale’s Woo-kyoung Ahn, the John Hay Whitney Professor of Psychology, a better understanding of these kinds of questions is crucial.

In her new book, “ Thinking 101: How to Reason Better to Live Better ,” Ahn explores the ins and outs of so-called “reasoning fallacies” — or, as she describes them, “thinking problems” — and how they affect our lives, from influencing how we view time to why we stereotype and profile other people. Her work examines the inherent complexities in the science of how we think and ultimately promotes solutions to overcome these reasoning fallacies.

The book is based on lessons Ahn teaches in her undergraduate course “Thinking,” which has become one of Yale’s most popular courses.

In an interview with Yale News, Ahn discusses the nuances of these “thinking problems” and the steps we should take to reduce biases. The interview has been edited and condensed.

The book is based on your popular course, “Thinking.” What inspired you to create the class itself — and to condense a semester-long course into a book?

Woo-kyoung Ahn: I have been teaching over 30 years and I have always covered some of these materials in various courses, and I was also teaching a seminar and an upper-level psych course on thinking too. But in 2016, I felt that it was time to disseminate this content more broadly for those who are not majoring in psychology.

The inspiration is this: it’s now quite well known that people commit a variety of reasoning fallacies, but they have been mostly discussed in the context of behavioral economics, or, to put it differently, psychology in the economic context. For example, people talked about the “negativity bias” — the bias to overweigh negative information compared to positive [information] — in terms of loss aversion in transaction or endowment effects. But I believe these irrational behaviors influence us in other situations in our everyday life. And I wanted to teach that rationality matters not just in dealing with money [and other material things] but much more broadly.

Another inspiration is that there has not been much discussion about what to do next once we notice that we commit thinking biases. Merely recognizing them isn’t enough; it’s like one can recognize that they have insomnia, but that’s not enough to cure insomnia. So, I’ve provided as many actional strategies as possible.

Which concepts did you choose to highlight in the book – and how did you choose to focus on them?

Ahn: In the course I cover many topics, like creativity, moral judgments, effects of language on thoughts, among many others — which I might, or might not, cover in a book at another time. But to be honest, I really have no good answer as to why these were chosen; I could have written a completely different book with the same title! One thing that I tried was not to cover too much in a single book. There are now websites with titles like “61 Cognitive Biases.” I just don’t want to overwhelm the readers. I also cover in the course more technical issues, [like] models of causal learning or mathematical proofs for irrational choices, which I don’t think was needed for a book written for the general public.

One valuable insight that became a running theme for the book is that these thinking “problems” aren’t really about what is wrong with us. I’ve mentioned this issue in my course at times, but I became more convinced about it while writing the book.

How would you define or diagnose these “thinking problems”?

Ahn: The kind of bad thinking that I care most about is unfair thinking. We can be unfair to ourselves and also to others when we are inconsistent, biased, overconfident, or underconfident.

For example, I don’t think the well-known confirmation bias is necessarily a thinking problem.

It refers to a tendency to confirm what we hypothesize or what we believe. That is, we tend to search for evidence that supports what we believe or interpret evidence to fit with what we know. That sounds pretty bad, but it is actually a quite adaptive mechanism. For instance, you go to a Stop & Shop three miles away from your house, and you find that their apples are good. Next time when you want apples, you could try a different supermarket, but if your goal is to just get good apples, you might as well go to the same supermarket again. That is, when our goal is to survive, it’s a better bet to continue with what you know rather than to try to explore other possibilities.

The confirmation bias becomes a thinking problem when it makes us draw conclusions that are unfair to ourselves or others. For example, let’s say a CEO of a company hires only white people for their top executive positions. They all do a reasonably good job, so now the CEO believes that race matters and continues hiring only white people. However, this CEO hasn’t even checked what would have happened if non-white people had been hired for those positions.

The confirmation bias can even hurt those who commit it. An experiment I conducted illustrates this. In the experiment, participants carried out a saliva test. Half the participants were told that the test results indicated that they have elevated genetic risks for major depressive disorder, and the other half were told that they don’t have the risks. Then, we asked all participants about the symptoms of depression they experienced in the past two weeks. These participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions, so there’s no reason why one group would have been more depressed for the last two weeks than the other.

But those who learned that they have genetic risks for major depression reported that they were significantly more depressed, and their average score is higher than what could be clinically considered mild depression.

One recurring theme of the book is how we might better communicate ideas, especially when there is evidence that using metrics — like data, statistics, et cetera — may be ineffective. How do you think public messaging campaigns can best incorporate some of these ideas and concepts?

Ahn: I think public messaging campaigns should acknowledge how we’re wired. For instance, when a charity organization asks for donations, they shouldn’t use just statistics or abstract data, but also an anecdote of a person who suffers from the issues that they are concerned about. In my recent study, we presented highly disgusting pictures of COVID-19 to the participants: pictures of COVID toes, burials of those who died of COVID, et cetera. As we know, politically conservative people were generally less willing to comply with the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guidelines than politically liberal people, at least at the time of the study. However, when presented with these vivid examples of those who suffer from COVID-19, they became much more willing to comply with the guidelines.

You seem to be a big proponent of promoting greater dialogue between people, in that doing so will help combat many of these cognitive biases we have.

Ahn: Again, I tried to underscore that those who commit cognitive biases are not bad people; these errors are part of our highly adaptive cognitive mechanisms. Let’s return to confirmation bias again to illustrate this one more time. My favorite example is what happened when my son was four years old. He asked me why a yellow traffic light is called a “yellow” light. I didn’t understand the question but was patient enough to tell him that it’s called a yellow light because it’s yellow. Then he told me it’s [not yellow, but] orange. I said no way. He insisted that I just look at it, so I did. And it is orange.

I had no ulterior motives to call it a yellow light or to interpret the amber color as being yellow, but because everybody called it a yellow light, I saw it as being yellow all my life until he pointed it out. But what I committed was confirmation bias; I interpreted the color of a traffic light in light of what I already believe. We do this every moment in our lives. Thus, we shouldn’t think that those who disagree with our views are different kinds of people; they are just seeing the world from their point of view.

Of course, there are people with ulterior motives and self-righteous people, but if we are to start a dialogue, we should first recognize [the biases] we all share.

Also, because these biases are essential components of how we survive, they are not easy to counteract. So, sometimes, I do present actionable strategies — don’t guess what others might like, ask! — but in some cases, we may just need to try to focus on solving problems at hand rather than trying to change others.

Campus & Community

Social Sciences

Creating a culture of courage and collegiality in academia

Library Shelving Facility offers students a look behind the scenes

Ecology and equity – an interview with Rob Nixon

Sixteen global leaders named 2024 World Fellows

- Show More Articles

Ask Yale Library

My Library Accounts

Find, Request, and Use

Help and Research Support

Visit and Study

Explore Collections

Christian Ethics Guide: Decision Making

- Reference Works

- Journals & Databases

- Intro and History of

- Bioethics and Environment

- Contextual Ethics

- Denominational Studies

- Decision Making

- Ethics and Bible

- Globalization

- Virtue Ethics

- Other Social Topics

- Special Collections This link opens in a new window

- ATLA Religion Database

Moral Choices

Subject Headings

Christian ethics

Christian ethics--Biblical teaching

Critical thinking

Decision making--Moral and ethical aspects

- << Previous: Denominational Studies

- Next: Ethics and Bible >>

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2023 4:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/ethics

Site Navigation

P.O. BOX 208240 New Haven, CT 06250-8240 (203) 432-1775

Yale's Libraries

Bass Library

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Classics Library

Cushing/Whitney Medical Library

Divinity Library

East Asia Library

Gilmore Music Library

Haas Family Arts Library

Lewis Walpole Library

Lillian Goldman Law Library

Marx Science and Social Science Library

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Center for British Art

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

@YALELIBRARY

Yale Library Instagram

Accessibility Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Giving Privacy and Data Use Contact Our Web Team

© 2022 Yale University Library • All Rights Reserved

University Preparation for International High School Students

You are here.

Prepare Yourself for College in the U.S.

This five-week program is for international high school students with strong English skills who want to prepare for undergraduate study at an American university. You will improve your overall abilities in both spoken and written English, as well as your understanding of U.S. academic culture. Enjoy the opportunity to visit a variety of American university campuses in the northeastern part of the United States. All students in the program will be housed together with other pre-college students attending Yale Summer Session.

Date: Program Dates: July 1 - August 2, 2024 Application Deadline: May 6, 2024

Tip: Pre-College students who wish to apply to Yale Summer Session: Must be entering the senior year of high school (summer after junior year) or freshman year of college (summer after senior year). Must be 16 years of age or older by their program start date.

Our application for Summer 2024 courses and programs is now open.

University Preparation Daily Schedule*

*Individual student schedules may vary. This is for reference only.

Summer Courses for High School Students

Academic reading and writing.

Improve your reading and critical thinking skills to prepare for study in the U.S. This class also polishes your writing skills with daily, intensive practice. Writing exercises will emphasize grammatical accuracy, clarity of content, and fluency, while focusing on well-organized and effectively developed paragraphs and essays. In addition, learn about the research process—including paraphrasing, summary, and proper citation—in the context of writing longer papers.

- Expand your vocabulary and ability to use new words and word forms

- Improve your reading comprehension and speed and gain confidence in your ability to master difficult texts

- Write essays for college applications

Academic Listening and Speaking

Develop the confidence and skills you need to be an active learner in American university classes. This class is designed to be eclectic, broad, interesting, provocative, and interactive. Learn to analyze, synthesize, and produce facts and information, while also improving your critical thinking skills.

- Develop listening skills and improve your academic note-taking abilities

- Enhance your ability to interact, discuss, argue, debate and give oral reports

- Expand your vocabulary and review grammatical structures

- Practice interview skills for university admissions

Academic Coaching

Learn about the American university system and admissions process while improving your academic skills. Academic coaching will help you understand how you study and learn best, how you exercise your personal brand of leadership, and how to be more proactive in your life.

- Explore the different types of academic institutions

- Learn about the college application process

- Improve your study skills

Critical and Creative Thinking

Explore the nature and technique of critical thought—a process used to establish a reliable basis for our claims, beliefs, and attitudes about the world. Learn to use strategies, materials, and interventions in your own educational setting. This class also seeks to deepen your understanding of creativity by improving your creative problem-solving skills and enhancing your ability to promote these skills in others.

- Learn what critical thinking is and how to apply the skills and strategies of critical thinking in a wide variety of settings

- Develop critical thinking skills

- Make connections between critical thinking and practices in life and education

Evening Elective Classes

Choose one evening elective class in an area that interests you. Evening electives meet two evenings per week. Elective class offerings vary, but offerings may include:

- English Pronunciation

- TOEFL Practice

- SAT Practice

- Art Appreciation

- American Music

College Visits

During week five of the program, students will visit local colleges. There will be at least four college visits planned during this week. Some college visits in the past have included: Brown University, Quinnipiac University, Wesleyan University, and the University of Connecticut. College visits will be announced as soon as they are reserved.

Tuition and Fees

For other fees and residential costs, please visit our Tuition and Fees page . All tuition and fees, including room and meal charges, must be paid in full by Friday, June 7, 2024.

Financial Assistance

Yale Summer Session only offers financial assistance to Yale College students. Financial assistance is not available for visiting students at this time. Visiting students should contact the financial aid office at their home institutions to discuss their options for financial assistance.

Application Information

The application for the University Prep Program is now open.

When prompted to select a program in the application, select Yale Summer Sessio n. Then, select 2019 Session B: July 1 - August 2 (please note that this program is only three weeks as opposed to six weeks). You will see Preparation for International High School Students (SUMR S010) listed on the course selection page.

To be considered for admission, you must submit the following materials before May 20, 2019:

- Online application

- Application fee and visa processing fee

- Financial documents

- Photocopy of passport

- Two letters of recommendation

- High school transcript

This is a full time program. You may not take a second YSS course in addition to this program.

Point: Admissions Note Students wishing to apply to the University Preparation Program must currently be in their junior or senior year of high school. Sophomores (students who will be juniors in the fall) are not eligible to apply. Applicants must be 16 years of age or older by their program start date.

Summer 2019 application is now open.

Courses & Programs

- Courses at Yale

- Yale Summer Online

- Intensive English

- Postgraduate Seminar

- Law Seminar

- Business Seminar

- University Preparation

- Conservatory for Actors

- Yale Writers' Workshop

- Yale Young Writers' Workshop

- Programs Abroad

How to Read Others and Express Myself: Imagination and Critical Thinking

The Program

In the “How to Read Others and Express Myself: Imagination and Critical Thinking” program, to be held on August 14-15, 2021, Jinyi Chu, Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University, will introduce participants to the art of understanding others and expressing oneself through literature. By engaging with the world’s foremost thinkers and texts, participants will cultivate their imagination and develop their critical thinking skills, which are essential elements of a liberal arts education at a top university. Participants who choose to submit a 250-word short essay (modeled after admissions essays) will receive feedback for their work from Yale Center Beijing staff who have served as Yale College admissions interviewers.

- Overview: Five Dimensions of Literature

- Literature as Imagination

- Literature as Communication

- Literature as Representation

- Literature as Emotion

- Literature as Illumination

Language : The language of the program will be English .

The Speaker

Jinyi chu assistant professor of slavic languages and literature, yale university.

Jinyi Chu is Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University. He obtained his Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures from Stanford University. His research focuses on Russian Literature, Russo-Chinese cultural connections, and global modernism. He was also a visiting scholar of Russian Academy of Sciences and Fudan University. He translated Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time and Smugglers, Rebels, Pirates: Itineraries in the Publishing History of ‘Doctor Zhivago’. He is now working on a Book Project of Russian Modernism’s China: Fin-de-siècle Geopoetics.

Offline Participation

- Regular 4,999元 , Flash Sale RMB 3,999

- At least 2 persons or more Group Discount Price RMB 3,599

Fees cover lunches and refreshments. All fees are non-refundable.

- Lectures and discussions: Saturday, Aug 14, 9:30-10:40, 11:00-12:10, 13:30-14:40, 15:00-16:10; Sunday, Aug 15, 9:30-10:40, 11:00-12:10

- Lunch: Saturday, Aug 14, 12:10-13:30; Sunday, Aug 15, 12:10-13:30

- Closing Ceremony: Sunday, Aug 15 afternoon

- 6 70-minute in-person lectures and discussion sessions (a total of 7 hours) with Prof. Chu

- Pre-program reading of 5 selected short literary pieces

- Participants may opt to submit a short essay (<250 words), modeled after typical admissions essays, to receive feedback from Yale College admissions interviewers.

*Those who attend 100% of the sessions will each receive a certificate of completion.

Yale Center Beijing 36th Floor Tower B of IFC Building 8 Jianguomenwai Avenue Chaoyang District, Beijing (Yong'anli Subway Station, Exit C)

Online Participation

- Regular 4,599元 , Flash Sale RMB 3,599

- At least 2 persons or more Group Discount Price RMB 3,199

Fees DO NOT cover lunches and refreshments. All fees are non-refundable.

- Saturday, Aug 14, 9:30-10:40, 11:00-12:10, 13:30-14:40, 15:00-16:10

- Sunday, Aug 15, 9:30-10:40, 11:00-12:10

Participation Format

*Please download and install the Zoom Application beforehand. Yale Center Beijing’s staff will contact confirmed participants for further testing in advance of the program to ensure a pleasant experience.

Registration:

To apply, scan the QR code below, or click HERE .

Contact person of Yale Beijing Center Phone: +86 139 1131 9551

Yale Center Beijing Liberal Arts Forum

Yale Center Beijing aims to bring the best of Yale to China and enable people in China to be exposed to the “best and brightest” at Yale.

A key aspect of the quintessential Yale experience is the commitment to liberal arts education. In hopes of creating a platform for next generation leaders to engage in intellectual exchange and discover new interests and abilities, Yale Center Beijing is launching the Yale Liberal Arts Forum series for eligible participants to experience the essence of liberal arts.

Through interacting with Yale faculty and thought leaders of various fields, participants will engage in critical thinking, evidence-based discussions, and collaborative activities, which are the keystones of a liberal arts education so as to better tackle issues in an ever-changing, complex, and globally interconnected world.

Public Event

Academic Requirements

Yale College’s academic requirements are designed to ensure that all students are exposed to a broad variety of fields of inquiry and approaches to knowledge.

Yale College's academic requirements, together with a student’s major requirements, comprise the foundation of an undergraduate education at Yale. As students fulfill the area and skills distributional requirements, they engage in critical thinking across a wide variety of disciplines.

Area Requirements

- two course credits in the humanities and arts

- two course credits in the sciences

- two course credits in the social sciences

Skills Requirements

- two course credits in quantitative reasoning

- two course credits in writing

- course(s) to further their foreign language proficiency

Depending on their level of language proficiency at matriculation, students may fulfill the foreign language requirement with one, two, or three courses or by a combination of course work and approved study abroad. The Language Chart offers an overview of language requirements for most students. Students from non-English-speaking countries who demonstrate native proficiency in a language other than English should consult their residential college dean.

Academic Requirement Resources

For more information, see the pages on Distributional Requirements and Requirements for the B.A. or B.S. Degree in the Yale College Programs of Study.

- Distributional Requirements (YCPS) catalog.yale.edu external

- Requirements for the B.A. or B.S. Degree (YCPS) catalog.yale.edu external

- Yale College Programs of Study (YCPS) catalog.yale.edu external

- Foreign Language Chart arrow

- Distributional Requirement Chart (PDF) file

Recently Visited

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

How Social Media Rewards Misinformation

A majority of false stories are spread by a small number of frequent users, suggests a new study co-authored by Yale SOM’s Gizem Ceylan. But they can be taught to change their ways.

- Gizem Ceylan Postdoctoral Researcher, Yale School of Management

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, posts and videos promoting natural remedies for the virus—everything from steam inhalation to ginger— proliferated online . What explains the storm of likes and shares that propels online misinformation through a social media network?

It’s not that people are lazy or don’t want to know the truth. The platforms’ reward systems are wrong.

Some scholars suggest that people share falsehoods out of bias, while others argue that failures of critical thinking or media literacy are to blame. But new research from Gizem Ceylan, a postdoctoral scholar at Yale SOM, suggests that these explanations miss something important. In a new study co-authored by Ian Anderson and Wendy Wood of the University of Southern California, Ceylan found that the reward systems of social media platforms are inadvertently encouraging users to spread misinformation.

By constantly reinforcing sharing—any sharing—with likes and comments, platforms have created habitual users who are largely unconcerned with the content they post. And these habitual users, the research shows, spread a disproportionate share of misinformation.

“It’s not that people are lazy or don’t want to know the truth,” Ceylan says. “The platforms’ reward systems are wrong.”

The researchers conducted several experiments to test how different kinds of social media users interact with true and false headlines. In the first, they asked participants to review eight true and eight false headlines and decide whether to share them to a simulated Facebook feed. They also asked several questions designed to assess how habitually participants used Facebook—that is, how much time they spent on the platform and how automatically they shared content.

The results showed that, overall, participants shared many more true headlines than false ones. However, the patterns were markedly different for the most habitual Facebook users. These participants not only shared more headlines overall, but also shared a roughly equal percentage of true (43%) and false (38%) ones. Less frequent users, by contrast, shared 15% of true and just 6% of false headlines.

Ceylan and her co-authors calculated that the 15% most habitual Facebook users were responsible for 37% of the false headlines shared in the study, suggesting that a relatively small number of people can have an outsized impact on the information ecosystem.

But why do the heaviest users share the most misinformation? Is it because the misinformation is in line with their beliefs? Not so, a subsequent experiment found. Habitual users will even share misinformation that goes against their political beliefs, the researchers discovered.

In this experiment, Ceylan and her colleagues asked participants to consider headlines that reflected partisan bias. Then, they examined concordant sharing (that is, liberals sharing liberal headlines or conservatives sharing conservative headlines) and discordant sharing (Iiberals sharing conservative headlines and vice-versa) among both habitual Facebook users and less frequent ones.

Interestingly, while less frequent users showed a stark preference for sharing concordant as compared to discordant headlines (that is, reflecting the partisan bias found in prior research), the pattern was less marked among the heaviest users. These habitual users shared more overall and also showed a less strong preference for concordant as compared to discordant information—another indication that habit was driving their behavior.

To Ceylan, this does not suggest that heavy Facebook users are not ideologically motivated or lazy in their processing when they spread misinformation. Instead, when users’ sharing habits are activated with cues from the social platform, the content they are sharing—its accuracy and partisan slant—is largely irrelevant to them. They post simply because the platform rewards posting with engagement in the form of likes, comments, and re-shares.

“This was kind of a shocker for the misinformation research community,” she says. “What we showed is that, if people are habitual sharers, they’ll share any type of information, because they don’t care [about the content]. All they care about is likes and attention. The content that gets attention become part of habitual users’ mental representations. Over time, they just share content that fits this mental representation. Thus, rewards on a social platform are critical in shaping people’s habits and what they are attuned to share with others.”

It’s a system issue, not an individual issue. We need to create better environments on social media platforms to help people make better decisions.

The study also suggests a potential way out of this trap. In their last experiment, the researchers simulated a new structure that rewarded participants for accuracy. When they share accurate information, participants were awarded points that were redeemable for an Amazon gift card.

“In this simulation, everyone shared lots of true headlines and few false headlines. Their previous social media habits did not matter,” Ceylan explains. “What this means is that, when you reward people for accuracy, people learn the type of content that gets rewards and build habits for sharing that content (i.e., accuracy in this case).” What’s more, surprisingly, the users continued to share accurate headlines even after the researchers removed the reward for accuracy. These results show that users can be incentivized to develop a new habit: accuracy.

To Ceylan, the research demonstrates how powerfully social media has shaped our habits. Platforms aim for more profit and engagement —i.e., more users spending longer hours using them. By rewarding and amplifying any type of engagement regardless of its quality or accuracy, platforms have created users who will share indiscriminately. “It’s a system issue, not an individual issue. We need to create better environments on social media platforms to help people make better decisions. We cannot keep on blaming users for showing political biases or being lazy for the misinformation problem. We have to change the reward structure on these platforms.”

Academic Skills

- Academic Skills Home

- Learning Preference

- Identifying and Leveraging your Support Systems

- Critical Thinking Skills

Defining Critical Thinking

Blooms taxonomy, student experience feedback buttons.

- Professional Communication

- Achieving Balance: Structure and schedule

- Time Management

- Overcoming Coursework Challenges

- Taking Ownership of your Success

- Success Tips from your AFA

- Utilizing Faculty Feedback

- ASC Writing Resources Guide This link opens in a new window

- Academic Integrity Basics

- Academic Integrity Violation (AIV) and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Self Plagiarism

- Academic Integrity Checklist

- Turnitin and Draft Coach

- Organization and Format

- Reviewing, Revising, Proofreading and Editing

- NU Library Research Process Guide This link opens in a new window

“Critical thinking relies on content, because you can't navigate masses of information if you have nothing to navigate to.” -Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Professor of Psychology, Temple University

One of the most sought-after skills in nearly every workplace is critical thinking (Doyle, 2018, October 30). But what is critical thinking, exactly? Better yet … what does it take to think critically? To some, it is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment; for others, it simply involves thinking “outside-the-box”. Either way, to think critically is to possess the unique ability to think reflectively and independently in order to make thoughtful decisions (Figliuolo, 2016, August 2). In other words, critical thinking is not just the accumulation of facts and knowledge; rather, it’s a process of approaching whatever is on your mind in order to come up with the best possible conclusion (Patel, 2018, October 24). Figure 1 illustrates the critical thinking process.

Figure 1. Critical thinking process

Three Essential Skills

To think critically, it begins with three essential skills:

- linking ideas,

- structuring arguments, and

- recognizing incongruences.

In order for you to become a better critical thinker, each of the three skills needs to be practiced and applied accordingly. The first skill, linking ideas, involves finding connections between seemly unrelatable, even irrelevant ideas, thoughts, etc. The second skill involves creating structured practical, relevant, and sound arguments. Lastly, to recognize incongruences is to find the real truth by being able to find holes in a theory or argument (MindValley, n.d.).

Food for Thought “No problem can withstand the assault of sustained thinking.” -Voltaire, French philosopher

Six Low-Level Questions

Once you have the three essential skills down, then you can ask yourself six low-level questions that you can use in nearly any situation (TeachThought Staff, 2018, July 29):

- What’s happening? Here, you will need to establish the basics and begin forming questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why the situation at hand is or is not significant.

- What don’t I see? Ask yourself whether or not there is any important information you might be missing.

- How do I know? Ponder on not only how you know what you think you know, but how that thought process was generated.

- Who is saying it? Identify the speaker and their position on the situation, then consider how that position could be influencing that person’s thinking.

- What else? What if? Think of anything else you be considering when making your decision. In addition, ponder the repercussions of what you’ve considered that might change/alter the outcome of your decision.

Food for Thought “Learn to use your brain power. Critical thinking is the key to creative problem solving in business.” -Richard Branson, Entrepreneur

In order to better understand higher-level critical thinking, it helps to be familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy, a classification of educational objectives and skills that educators establish for their students. In Bloom’s Taxonomy, there are three overarching domains known as KSA: (a) Knowledge [cognitive], (b) Skills [psychomotor], and (c) Attitudes [affective]. This taxonomy of learning behaviors is referred to as “the goals of the learning process.” In other words, after a period of learning, the student will have acquired a new knowledge, skill and/or attitude (Bloom et al., 1956). In this resource, we will focus on the Knowledge (cognitive) domain. According to Bloom et al. (1956), the cognitive domain involves the development of intellectual skills. There are six major categories of the cognitive process (Figure 2), beginning with the development with the simplest skills (e.g., remembering basic facts and concepts), through a learning of procedural patterns and concepts that facilitate the development of intellectual abilities, before eventually moving to the highest, most complex skills (e.g., creation of new or original ideas).

Figure 2. Bloom's Taxonomy

- To further explain, the first level of Bloom’s Taxonomy involves remembering specific information. This includes recalling basic vocabulary, dates, and math facts.

- Moving up the taxonomy, understanding is demonstrated by a student’s ability to comprehend, organize, compare and to verbalize main concepts. At this level, questions require the ability to understand meaning, not just basic facts. For example, a study might be asked to explain the difference between apples and oranges.

- The third level, application, is being able to actually use the new knowledge. Within this level, questions often require the student taking what s/he just learned, then applying it in a different way. For example, the student may be asked to take a list of food items, then select four items to make a healthy breakfast.

- The next level, analysis, involves breaking down information into different parts for a more thorough examination. Here, questions require proven facts (evidence) to support the answer. For example, the student is asked to compare and contrast Republicans to Democrats with regard to their views on supporting or repealing the Affordable Care Act.

- Evaluation, the fifth level, is the ability to make judgments about information by presenting and defending one’s own opinions. It is important to note that at this level, questions don’t necessarily have a right (or wrong) answer. For example, a student may be asked how s/he would handle observing a friend who cheated on a final exam.

- The top of the taxonomy involves the synthesis of new information and compiling it in new ways. It is at this level where more abstract, creative, “outside-the-box” thinking comes into play. For example, a student may be asked to design and construct a robot that can walk a certain distance.

While the first three levels of the taxonomy are important to solidify core knowledge, it is within the last three levels – analysis, evaluation, and creativity – that require critical thinking skills. (Anderson et al., 2001).

Practice Activity

In a study by Gottfried and Shearer (2016, May 26), the authors stated that 62% of adults get their news from social networking sites. In fact, the results show that 70% of Reddit users, 66% of Facebook users, and 59% of Twitter users get their news from one or more of these platforms. According to the study, among these three social networking sites, Facebook had the greatest reach with 67% of American adults using the platform. This suggests that the two-thirds of adults who use Facebook to get their news, which amount to 44% of the general population. Unfortunately, social media platforms don’t go through the stringent review process to which most major news outlets are required in order to be in compliance with Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations. Therefore, information can be shared publicly without “fact-checking” to make sure that what’s being shared is truly accurate. With this in mind, one can’t help but ask: What’s the truth versus what isn’t? Better yet … what’s real news and what’s fake?

Your task involves the use of Bloom’s Taxonomy to decipher “fake news” from real news. Using the eight-step infographic on the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) website (https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11174) as a guide, review the following news stories to determine which are real and which are fake. Explain your rationale.

1. Strasbourg market attacker ‘pledged allegiance to ISIS’ – source.

2. Lawmakers in California propose a new law called the “Check Your Oxygen Privilege Act”.

3. Four AI-controlled robots kill 29 scientists in Japan.

4. North Korea says it will not denuclearize until the US eliminates ‘nuclear threat’.

5. Two men found living underneath the Calico Mine Ride at Knott’s Berry Farm.

6. Scientists find a brain circuit that could explain seasonal depression.

7. Amazon customer receives 1,700 audio files of a stranger who used Alexa.

8. NFL fines Pittsburgh Steelers $1M each for skipping National Anthem.

9. FBI raids CDC for data on vaccines and autism.

10. Only 60 of 1,566 churches in Houston opened to help Hurricane Harvey victims.

References:

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York, NY: Pearson, Allyn & Bacon. Bloom, B. (Ed.), Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, NY: McCay. Doyle, A. (2018, October 30). Critical thinking definition, skills, and examples. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/critical-thinking-definition-with-examples-2063745 Figliuolo, M. (2016, August 2). Critical thinking. Retrieved from https://www.lynda.com/Business-Skills-tutorials/Critical-Thinking/424116-2.html Gottfried, J., & Shearer, E. (2016, May 26). News use across social media platforms 2016. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2016/ MindValley. (n.d.). How to solve the biggest problems with critical thinking exercises [blog]. Retrieved from https://blog.mindvalley.com/critical-thinking-exercises/# Patel, D. (2018, October 24). 16 characteristics of critical thinkers. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/321660 TeachThought Staff. (2018, July 29). 6 critical thinking questions for any situation. Retrieved from https://www.teachthought.com/critical-thinking/6-critical-thinking-questions-situation/

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Identifying and Leveraging your Support Systems

- Next: Professional Communication >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 7:59 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/ata/academicskills

- Yale Directories

Institution for Social and Policy Studies

Advancing research • shaping policy • developing leaders, the dispersion of power: samuel bagg’s urgent call to redefine democracy.

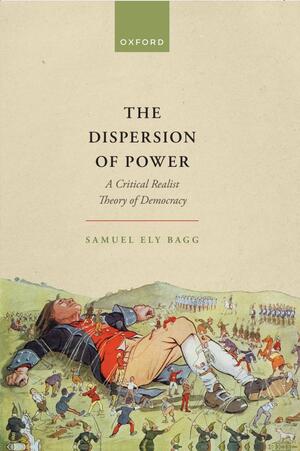

Samuel Bagg’s publisher, Oxford University Press, bills his new book, “The Dispersion of Power” as “an urgent call to rethink centuries of conventional wisdom about what democracy is, why it matters, and how to make it better.”

But it wasn’t always so urgent.

The book began more than a decade ago as his Ph.D. thesis, which was a largely theoretical exploration of democracy. And after the domestic and global political “upheavals” of the late 2010s, he felt he needed to grapple more directly with the demands of democracy in practice.

“It quickly became clear to me that my issues with common ways of thinking about democracy weren’t just abstract — they had real consequences,” Bagg said. “I wanted to highlight those consequences and show how thinking differently about democracy could help us get out of some of the problems that we’re now facing.”

The Institution for Social and Policy Studies’ Democratic Innovations Program invited Bagg, an assistant professor of political science at South Carolina University , for a two-week residency at Yale, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Ethics, Politics, and Economics in 2009. Democratic Innovations seeks to identify and test new ideas for improving the quality of democratic representation and governance.

“We could not be happier to have Sam here for what has been a wonderfully productive and thought-provoking visit,” said Alan Gerber, director of ISPS and Sterling Professor of Political Science. “Sam’s sharp, compelling work deploys political science, history, psychology, and critical theory to challenge common views of democracy. He is asking big questions, pointing toward new and hopefully more effective ways of dealing with the problem of special interest capture of policymaking so we can build a more functional and equitable society.”

During his stay, we spoke with him about his new book and how he envisions democracy’s purpose not primarily as the expression of a population’s collective self-rule but as the need to prevent the capture of state power by private interests.

ISPS: You note in your book’s conclusion that you intentionally de-emphasized current specific challenges to democracy, such as polarization and disinformation, which are now roiling politics in the United States, Brazil, India, Hungary, Turkey and elsewhere. Why make that choice?

Sammuel Bagg: The first reason is just that many other people have been writing about those issues. So, they are important, and we need to address them directly, but I didn’t know how much I had to add to what’s already been said. The place where I saw a gap is that when people discuss those problems, they are not always getting at the underlying issues causing them. They are often looking at the symptoms, which are important to consider. But it’s also important to see where those symptoms come from and address those causes as well.

ISPS: And in the case of challenges to democracy, you argue the underlying causes relate primarily to power dynamics.

SB: Exactly. The electoral institutions we have, the rights that are protected, the way people access trustworthy information — all these things are crucial, and they are all under threat right now. So, we need to protect them. But unless we address underlying imbalances of economic and social power, similar threats are going to keep emerging.

ISPS: You write about how the power imbalance itself has not been the primary focus of most democratic theorists and reformers. Why do you think that is?

SB: Most of us associate the idea of democracy with processes of collective decision-making on equal terms, or in other words, collective self-rule. For some people, that ideal is realized by the way we elect representatives. Plenty of others see that our current systems do not reflect everyone’s views equally, and they look for other methods of incorporating people’s views, preferences, and ideas on a more equal basis more directly into decision-making. Maybe that means people need to have a more direct say in politics through referendums. Or maybe we need smaller-scale deliberative bodies to define people’s preferences and then incorporate them into decisions.

SB: I think many people recognize that improving democracy is going to require confronting the wealthy and powerful groups who currently dominate our political and economic systems. The issue that I have is not with the diagnosis of the problem, which a lot of people share. The problem comes when they suggest that the way to fix the problem is to fix the decision-making procedures. I agree that it could help on the margins. Some ways of making decisions are certainly fairer and better than others. But I believe that focusing exclusively on it will just lead us into a kind of never-ending cycle of reform and disappointment. Because whatever set of procedures we settle on will never be enough. Whatever institutions we use will still be influenced by these underlying imbalances of power.

ISPS: You said earlier that most people mistakenly define democracy as collective self-rule. Are you saying that collective self-rule is not necessary to a functioning society so long as state institutions operate for the public good?

SB: I would say the problem I have with collective self-rule has to do primarily with the way it structures our aspirations for reform. Because it focuses our attention on these particular decision-making procedures. We can still uphold self-rule as an abstract ideal and just reinterpret what it requires in practice in terms of resisting the capture of state power.

ISPS: So it can be an important ideal, just not the only one.

SB: Some people are very committed to this idea of collective self-rule, believing that’s just what democracy means. I say, great. The best way to achieve the outcome you want is to focus less on decision-making procedures and more on the underlying distribution of power.

ISPS: You devote a chapter to providing a realistic defense of elections without inflating the legitimacy or authority of their results. Why should we support such a flawed system?

SB: It’s true that I don’t think that elections and universal suffrage help achieve collective self-rule, which, as discussed, many people treat as a valuable ideal. There are too many problems identifying electoral procedures as a means for reflecting the unique individual will of each person and allowing them to make decisions on equal terms. That is simply not what elections do.

ISPS: Don’t elections at least provide some accountability for elected officials?

SB: The accountability offered by elections is extremely attenuated. You often have only a couple of choices, and trying to evaluate someone on thousands of policy decisions — all at once — it’s just way too much.

ISPS: And yet you still think elections are valuable. Why?

SB: For any response to any political problem, elections with universal suffrage are absolutely necessary. The reason is simply that any other way of selecting the leaders in a gigantic modern state enables those leaders or those affiliated with them to accrue too much power and corrupt the power of the state for their own private interests. Of course, they can still do that to some extent under an electoral system, which is why they are not perfect. But compared to all the other ways that people compete for power, democratic elections are more transparent, more open, and relatively peaceful. They give at least some incentive to the people competing to gain the respect of and perhaps promote the interests of other groups. And elections incentivize candidates to frame their polices in terms of a broad public interest.

ISPS: Your book posits a negative goal of resisting state capture that you call “a deliberately imprecise term” … “designed to encompass an ever-shifting variety of concrete threats.” That sounds exhausting. How might reformers with this mindset rally public support to assume and indefinitely maintain this posture?

SB: Part of the reason people feel so despairing and disappointed is their expectations are set by this fantasy of collective self-rule, which is never going to be achieved. People have an idea that public policy should reflect their individual views. They feel they should be co-authors and co-owners of the law. And that if they don’t feel that way, then it’s not really a democracy.

ISPS: Are you proposing that American citizens reject the idea of collective self-rule? Even if it’s a fantasy, it’s a potent one that we learn in grade school.

SB: Sure. I don’t think it is necessarily a problem for the public to embrace collective self-rule as an abstract ideal. My argument is more about how we should best make use of limited resources. If our goal is to advance democracy, what is worth prioritizing in terms of time and money?

ISPS: And for the typical voter?

SB: I think they should reorient how they view their task as voters and citizens more broadly.

ISPS: Meaning?

SB: One of the reasons people hate voting for what they perceive as the lesser of two evils is they see democracy as this thing where they get to choose their favorite candidate. Someone who serves as an expression of their values and political ideals. But elections rarely if ever promise such a choice. If they do anything consistently, it’s that they prevent the worst kinds of outcomes, such as tyranny. If you want more than that, you need to do more than vote.

ISPS: Your remedies include what you call “the dramatic expansion of radical practices that redistribute private power.” What are some examples of these types of reforms?

SB: One helpful question to ask at the outset is what kind of structure of society we should look toward as a utopian horizon. What does it look like in this best possible world? For me, a lynchpin of that is something I call unconditional wealth transfers. This builds on the idea of a universal basic income (UBI). But UBI is only a floor, a minimum people need to survive. The idea of unconditional wealth transfer is the constant rebalancing of power.

ISPS: OK, that does sound radical. And utopian.

SB: Right. It’s an ideal. Something to work toward. Not to make sure everyone has a minimum of sufficiency but to make sure that nobody gets too wealthy compared to others.

ISPS: Importantly, you are not calling for pure socialism. Your reforms embrace economic competition.

SB: I certainly believe there’s a lot more room for public ownership and control of certain industries, such as health care. And at least some public participation in housing. At the same time, we definitely need to keep markets alive.

SB: There is a real danger in eliminating all private ownership and competition and placing it in public hands. Even in communist countries, someone always has outsized power. In the U.S.S.R., for example, nobody had any wealth, but power was distributed unequally through access to political officials, status within the ruling party, and so on. Who was going to live in the nicest apartments? It was not determined by the amount of money you had to spend but who was in with the right people. Markets throw some degree of unpredictability into the mix that shakes up hierarchies. We need private ownership and markets to sustain a dynamic society.

ISPS: OK, but setting aside the idealized utopian horizon, what are some reforms we might implement now to oppose state capture by private interests?

SB: I think there are three basic categories of reform. One is substantive policies to help transfer power. For example, Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Kahn is trying to enforce anti-trust policy more effectively. That’s an important way to reduce the kinds of concentrations of power that make capture more likely.

ISPS: What’s the second category of reform?

SB: Then there is procedural reform — changing not which policies are made, but rather how they are made. One example I discuss in the book is oversight by ordinary citizens, which is really important but also really difficult to get right. When you invite citizens into a process, there is a big power imbalance between them and the special interest groups that work in politics. These groups have much more experience, power, organization, and information. Nevertheless, it’s valuable to incorporate citizens precisely because they are not part of these networks of influence and capture. We need to find ways to make use of their unique ordinariness in ways that are not susceptible to the same types of influences.

ISPS: And the third type?

SB: The third category is the most important, and it exists outside the state entirely. To achieve policies that are going to genuinely threaten the influence of wealthy elites — the people too often making the rules — you first need to change the terrain, the balance of power. In order to do that, you have to make use of the power of numbers rather than wealth. You need to get people to build their collective ability to contest the power of these wealthy and entrenched elites.

ISPS: This is what you mean by “countervailing power” and “organizing for power.”

SB: That’s correct. If we are to overcome the influence of wealthy and entrenched interests on our government, we must cultivate robust and durable organizations that genuinely represent the interests of ordinary people and which are powerful enough to counterbalance those special interests.

ISPS: What might that look like?

SB: I realize that much of my book and our conversation might sound pessimistic. But we’ve seen similar efforts succeed before. History has shown us how something like the Montgomery bus boycott can threaten the material interests of people in power and force them to make concessions. Unions can go on strike. Teachers can demand changes to educational policy. As I write in the book, cracks always appear in the political order. There may be disagreements among elite factions or external shocks that offer openings to disrupt and redirect the way policy is made and carried out. Building organizations that can take advantage of those opportunities when they arise must be our first priority.

ISPS: Is your book cynical or realist? Is it both? Is cynicism a realistic way to view democratic governments in capitalistic societies?

SB: Well, I subtitled the book “A Critical Realist Theory of Democracy,” so I definitely consider myself a realist. And if a cynical point of view would be to expect the worst of everyone or everything, I guess a certain kind of cynicism can be useful.

ISPS: How so?

SB: The book makes a baseline assumption that most things we do are going to fail. Most forms of participation are going to be coopted by elites. Most forms of organization are not going to be effective at countering elite power. You have to be incredibly skeptical and disciplined when thinking about how to use the limited resources we have. And you have to be skeptical, perhaps to the extent of cynicism, about proposals for making things better.

ISPS: Does that make you a pessimist?

SB: I’ll be the first to admit that the things that I think are most promising are not even that promising. They are just less likely to fail when compared to everything else. And maybe that is a kind of pessimism. But I prefer to think of it as realism. Because the point is not that progress is impossible. The point is that progress is really difficult and rare, and in order to get it, you have to be really clear-eyed about what the obstacles are. So, whatever we call it, I firmly believe that this kind of perspective is necessary to at least have a chance of making things better.

- How to apply critical thinking in learning

Sometimes your university classes might feel like a maze of information. Consider critical thinking skills like a map that can lead the way.

Why do we need critical thinking?

Critical thinking is a type of thinking that requires continuous questioning, exploring answers, and making judgments. Critical thinking can help you:

- analyze information to comprehend more thoroughly

- approach problems systematically, identify root causes, and explore potential solutions

- make informed decisions by weighing various perspectives

- promote intellectual curiosity and self-reflection, leading to continuous learning, innovation, and personal development

What is the process of critical thinking?

1. understand .

Critical thinking starts with understanding the content that you are learning.

This step involves clarifying the logic and interrelations of the content by actively engaging with the materials (e.g., text, articles, and research papers). You can take notes, highlight key points, and make connections with prior knowledge to help you engage.

Ask yourself these questions to help you build your understanding:

- What is the structure?

- What is the main idea of the content?

- What is the evidence that supports any arguments?

- What is the conclusion?

2. Analyze

You need to assess the credibility, validity, and relevance of the information presented in the content. Consider the authors’ biases and potential limitations in the evidence.

Ask yourself questions in terms of why and how:

- What is the supporting evidence?

- Why do they use it as evidence?

- How does the data present support the conclusions?

- What method was used? Was it appropriate?

3. Evaluate

After analyzing the data and evidence you collected, make your evaluation of the evidence, results, and conclusions made in the content.

Consider the weaknesses and strengths of the ideas presented in the content to make informed decisions or suggest alternative solutions:

- What is the gap between the evidence and the conclusion?

- What is my position on the subject?

- What other approaches can I use?

When do you apply critical thinking and how can you improve these skills?

1. reading academic texts, articles, and research papers.

- analyze arguments

- assess the credibility and validity of evidence

- consider potential biases presented

- question the assumptions, methodologies, and the way they generate conclusions

2. Writing essays and theses

- demonstrate your understanding of the information, logic of evidence, and position on the topic

- include evidence or examples to support your ideas

- make your standing points clear by presenting information and providing reasons to support your arguments

- address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints

- explain why your perspective is more compelling than the opposing viewpoints

3. Attending lectures

- understand the content by previewing, active listening , and taking notes

- analyze your lecturer’s viewpoints by seeking whether sufficient data and resources are provided

- think about whether the ideas presented by the lecturer align with your values and beliefs

- talk about other perspectives with peers in discussions

Related blog posts

- A beginner's guide to successful labs

- A beginner's guide to note-taking

- 5 steps to get the most out of your next reading

- How do you create effective study questions?

- An epic approach to problem-based test questions

Recent blog posts

Blog topics.

- assignments (1)

- Graduate (2)

- Learning support (25)

- note-taking and reading (6)

- organizations (1)

- tests and exams (8)

- time management (3)

- Tips from students (6)

- undergraduate (27)

- university learning (10)

Blog posts by audience

- Current undergraduate students (27)

- Current graduate students (3)

- Future undergraduate students (9)

- Future graduate students (1)

Blog posts archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (8)

- August (10)

Contact the Student Success Office

South Campus Hall, second floor University of Waterloo 519-888-4567 ext. 84410

Immigration Consulting

Book a same-day appointment on Portal or submit an online inquiry to receive immigration support.

Request an authorized leave from studies for immigration purposes.

Quick links

Current student resources

SSO staff links

Employment and volunteer opportunities

- Contact Waterloo

- Maps & Directions

- Accessibility

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations .

Yale Alumni Logo

Yale Day of Service: CT, Storrs - Invention Convention Judging

The Yale Club of Hartford invites you to join over 350 engineers, scientists, academics, entrepreneurs, and legal professionals who will judge student inventions and inspire young minds to pursue science and engineering. We have a unique opportunity to sponsor and judge the regional virtual event of hundreds of Connecticut student inventors who have prepared to demonstrate their achievement in creative and critical thinking skills and their active role as inventors.

The Yale Club of Hartford will select three inventors, representing an elementary, a middle, and a high school level. The three Yale Club awards will be presented during an in-person finals event on Saturday, June 8th at Gampel Pavilion on the campus of University of Connecticut.

Please consider volunteering some time to support our young inventors and/or sharing this invitation with any friends or colleagues who may want to judge!

Upcoming Events:

- Connecticut State Semi-Finals : April 5th-19th, Asynchronous Virtual Judging - Judge from Anywhere!

- Connecticut State Finals : Saturday, June 8th 2024, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

These registration forms are managed by the Connecticut Invention Convention team. If you decide to register as a judge, please note “Yale Club of Hartford” in the field for Employer.

Once you have registered, please e-mail Club of Hartford Vice President Katherine McCormack so we can include you on Team Yale Club of Hartford and keep you connected with other Club members who will be also be serving as judges, and also enter you onto the list for Yale Day of Service!

Thank you for supporting student innovation!

Contact: Katherine McCormack '81 MPH

- Get Involved ,

- Regional Clubs ,

You May Also Be Interested In

Yale day of service: ca, san diego - ocean beach clean up.

1950 Abbott Street San Diego , CA United States

Yale Day of Service: CA, Los Angeles - Elevating Foster Youth Futures

1370 N St Andrews Pl Los Angeles , CA 90028 United States

Yale Alumni Unscripted: Xiaoyan Huang ’91

Yale day of service: virtual - ct invention convention judging.

United States

COMMENTS

The Thinking Lab is directed by Woo-kyoung Ahn, Professor of Psychology, Yale University. We are interested in any topics related to thinking, including causal learning and reasoning, and concepts and categorization. We study not only basic issues, but also applied issues, such as how different kinds of causal explanations for mental disorders ...

Chapter 4: Increasing Critical Thinking and Motivation. Think for a moment about how you got here. Presumably you like doing what you do; you were probably naturally better at it and more interested in it than anything else you studied in college. You might think of "Yale" almost exclusively as the department in which you study.

Psych 179S: Thinking Summer, 2021 (Updated on Jan 25th, 2021) Instructor : Woo-kyoung Ahn e-mail: [email protected] Teaching Fellow: Emily Gerdin e-mail: [email protected] Course Description A survey of research findings and theories of how we "think," and their real-life applications.

Open Yale Courses provides free and open access to a selection of introductory courses taught by distinguished teachers and scholars at Yale University.The aim of the project is to expand access to educational materials for all who wish to learn. All lectures were recorded in the Yale College classroom and are available in video, audio, and text transcript formats

Some characteristics of critical thinking are: . Problem Solving . This is the process of finding solutions to difficult or complex issues. Analyzing and evaluating key information clearly and precisely. Extrapolate meaning from data and draw conclusions or inferences. Reflecting. Or Critical Reflection is a process of identifying, questioning ...

In organizations, critical thinking, problem solving, and decision making are among the most important tasks people perform on a daily basis. However, increasing levels of complexity can put a significant strain on our judgement, often leading to poor choices that can have a long-term impact. ... Yale University alumni; small groups of 3-6; and ...

Neat, clean, and appropriate attire and personal hygiene; a positive attitude, excellent attendance and acceptable standards of treatment in relationships with colleagues. Dressing for Success. Dealing with Disrespect. Office Politics and Gossip. Emotional Intelligence. Pursuing Excellence. Keeping the Gate. Personal Branding. Soft skills are ...

Bias on the brain: A Yale psychologist examines common 'thinking problems'. In her new book, "Thinking 101: How to Reason Better to Live Better," Woo-kyoung Ahn explores so-called "reasoning fallacies" and how they affect our lives. The sometimes counterintuitive ways that our brains work can raise big questions.

Scientific Thinking and Reasoning ANTH S018 SUMMER 2021 . Tuesdays/Thursdays 1 - 4:15 pm . Eduardo Fernandez-Duque . Professor . Anthropology and School of the Environment . I am writing this syllabus in mid-November 2020 when it is still uncertain what the situation will be like in Summer 2021. On normal semesters, the syllabus of my courses ...

This book is an introductory text on critical thinking for upper-level undergraduates and graduate students. It shows students how to think critically about key topics such as experimental research, statistical inference, case studies, logical fallacies, and ethical judgments. Robert J. Sternberg is Dean of Arts and Sciences at Tufts University.

CRITical Thinking is a blog written by staff, directors, and friends of the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT), a joint program of Yale Law School, Yale School of Public Health, and Yale School of Medicine. ... It does not purport to represent Yale University's institutional views, if any. No representation is made ...

Metrics. There are two popular views regarding the origin of critical thinking: (1) The concept of critical thinking began with Socrates and his Socratic method of questioning. (2) The term 'critical thinking' was first introduced by John Dewey in 1910 in his book How We Think. This paper argues that both claims are incorrect.

It makes you a well-rounded individual, one who has looked at all of their options and possible solutions before making a choice. According to the University of the People in California, having critical thinking skills is important because they are [ 1 ]: Universal. Crucial for the economy. Essential for improving language and presentation skills.

In essence, this critical analysis forms an integral part of our exploration into the rich tapestry of intellectual curiosity at Yale University, transcending mere historical documentation to ...

Critical thinking comprises the mental processes, strategies, and representations people use to solve problems, make decisions, and learn new concepts. The study of critical thinking combines the educational, philosophical, and psychological traditions of thought. R. Ennis offers a philosophical taxonomy suggesting that critical thinking results from the interaction of a set of dispositions ...

Ethical Argument: Critical Thinking in Ethics by Hugh Mercer Curtler This brief introduction combines a discussion of ethical theory with fundamental elements of critical thinking--including informal fallacies and the basics of logic--and uses case studies and practical applications to illustrate concepts.