- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

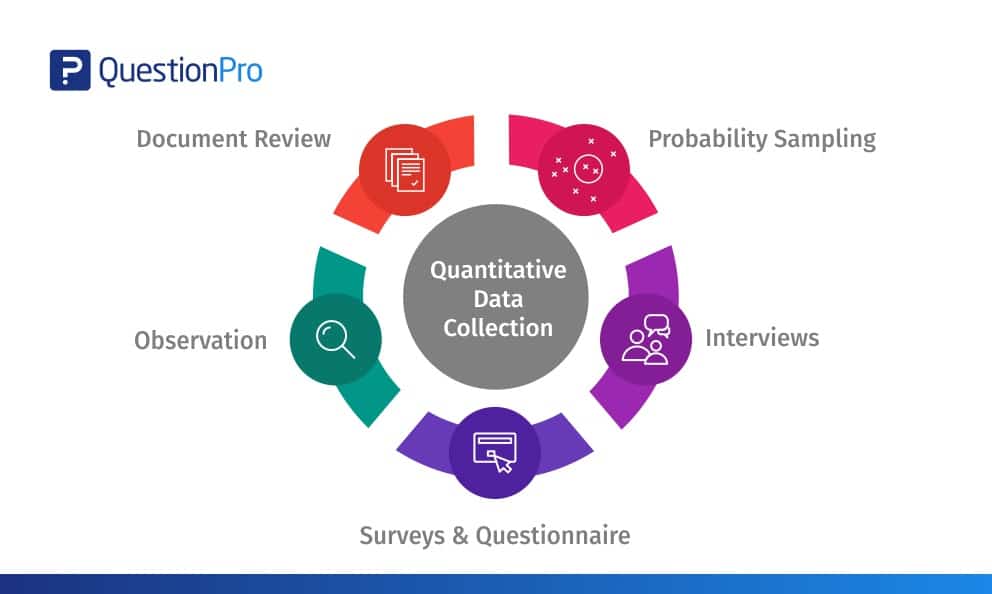

Quantitative Data Collection: Best 5 methods

In contrast to qualitative data , quantitative data collection is everything about figures and numbers. Researchers often rely on quantitative data when they intend to quantify attributes, attitudes, behaviors, and other defined variables with a motive to either back or oppose the hypothesis of a specific phenomenon by contextualizing the data obtained via surveying or interviewing the study sample.

Content Index

What is Quantitative Data Collection?

Importance of quantitative data collection, probability sampling, surveys/questionnaires, observations, document review in quantitative data collection.

Quantitative data collection refers to the collection of numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical methods. This type of data collection is often used in surveys, experiments, and other research methods. It measure variables and establish relationships between variables. The data collected through quantitative methods is typically in the form of numbers, such as response frequencies, means, and standard deviations, and can be analyzed using statistical software.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

As a researcher, you do have the option to opt either for data collection online or use traditional data collection methods via appropriate research. Quantitative data collection is important for several reasons:

- Objectivity: Quantitative data collection provides objective and verifiable information, as the data is collected in a systematic and standardized manner.

- Generalizability: The results from quantitative data collection can be generalized to a larger population, making it an effective way to study large groups of people.

- Precision: Numerical data allows for precise measurement and unit of analysis , providing more accurate results than other data collection forms.

- Hypothesis testing: Quantitative data collection allows for testing hypotheses and theories, leading to a better understanding of the relationships between variables.

- Comparison: Quantitative data collection allows for data comparison and analysis. It can be useful in making decisions and identifying trends or patterns.

- Replicability: The numerical nature of quantitative data makes it easier to replicate research results. It is essential for building knowledge in a particular field.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Overall, quantitative data collection provides valuable information for understanding complex phenomena and making informed decisions based on empirical evidence.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Methods used for Quantitative Data Collection

A data that can be counted or expressed in numerical’s constitute the quantitative data. It is commonly used to study the events or levels of concurrence. And is collected through a Structured Question & structured questionnaire asking questions starting with “how much” or “how many.” As the quantitative data is numerical, it represents both definitive and objective data. Furthermore, quantitative information is much sorted for statistical analysis and mathematical analysis, making it possible to illustrate it in the form of charts and graphs.

Discrete and continuous are the two major categories of quantitative data where discreet data have finite numbers and the constant data values falling on a continuum possessing the possibility to have fractions or decimals. If research is conducted to find out the number of vehicles owned by the American household, then we get a whole number, which is an excellent example of discrete data. When research is limited to the study of physical measurements of the population like height, weight, age, or distance, then the result is an excellent example of continuous data.

Any traditional or online data collection method that helps in gathering numerical data is a proven method of collecting quantitative data.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Sampling

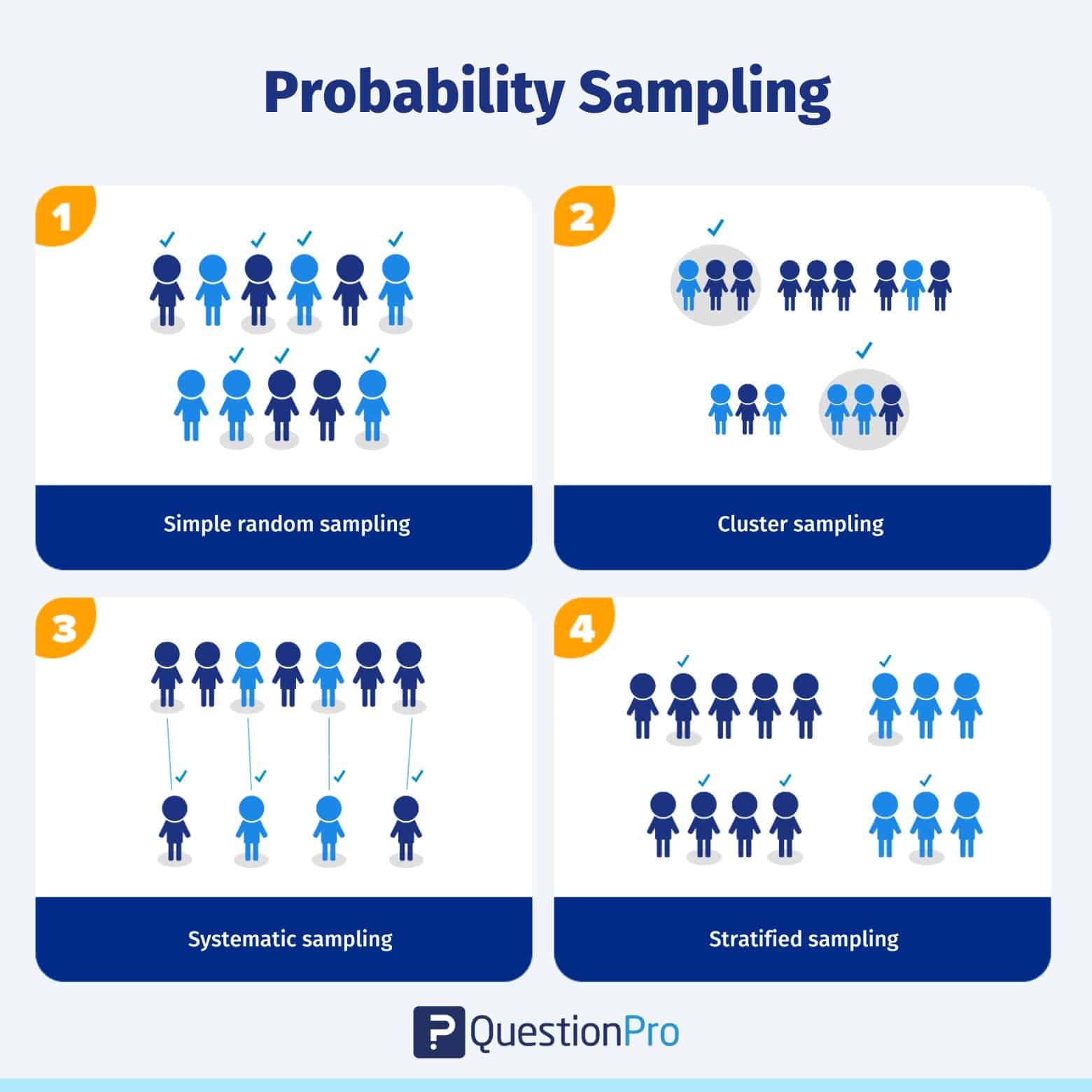

There are four significant types of probability sampling:

- Simple random sampling : More often, the targeted demographic is chosen for inclusion in the sample.

- Cluster sampling : Cluster sampling is a technique in which a population is divided into smaller groups or clusters, and a random sample of these clusters is selected. This method is used when it is impractical or expensive to obtain a random sample from the entire population .

- Systematic sampling : Any of the targeted demographic would be included in the sample, but only the first unit for inclusion in the sample is selected randomly, rest are selected in the ordered fashion as if one out of every ten people on the list .

- Stratified sampling : It allows selecting each unit from a particular group of the targeted audience while creating a sample. It is useful when the researchers are selective about including a specific set of people in the sample, i.e., only males or females, managers or executives, people working within a particular industry.

Interviewing people is a standard method used for data collection . However, the interviews conducted to collect quantitative data are more structured, wherein the researchers ask only a standard set of online questionnaires and nothing more than that.

There are three major types of interviews conducted for data collection

- Telephone interviews: For years, telephone interviews ruled the charts of data collection methods. Nowadays, there is a significant rise in conducting video interviews using the internet, Skype, or similar online video calling platforms.

- Face-to-face interviews: It is a proven technique to collect data directly from the participants. It helps in acquiring quality data as it provides a scope to ask detailed questions and probing further to collect rich and informative data. Literacy requirements of the participant are irrelevant as F2F surveys offer ample opportunities to collect non-verbal data through observation or to explore complex and unknown issues. Although it can be an expensive and time-consuming method, the response rates for F2F interviews are often higher.

- Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI): It is nothing but a similar setup of the face-to-face interview where the interviewer carries a desktop or laptop along with him at the time of interview to upload the data obtained from the interview directly into the database. CAPI saves a lot of time in updating and processing the data and also makes the entire process paperless as the interviewer does not carry a bunch of papers and questionnaires.

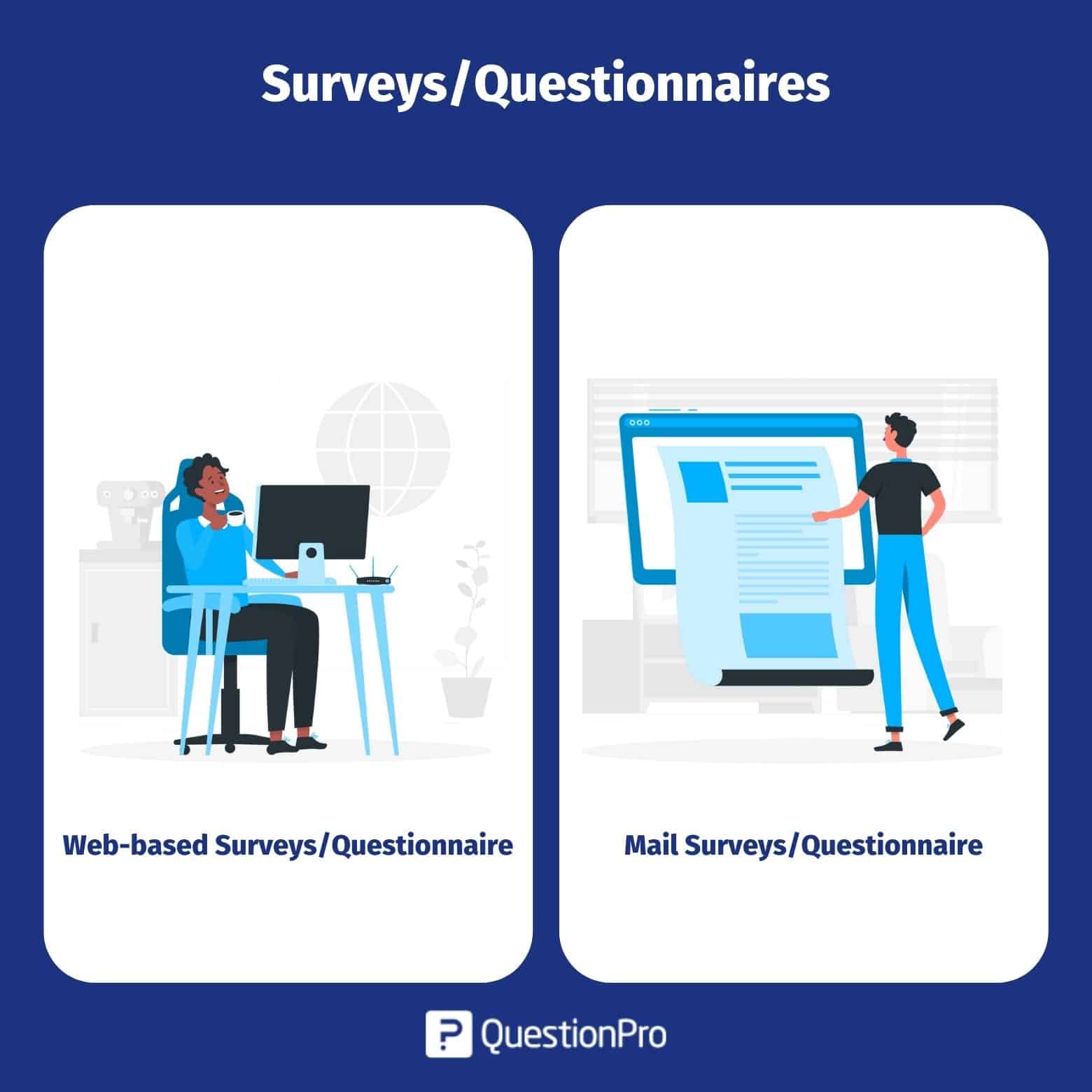

There are two significant types of survey questionnaires used to collect online data for quantitative market research.

- Web-based questionnaire : This is one of the ruling and most trusted methods for internet-based research or online research. In a web-based questionnaire, the receive an email containing the survey link, clicking on which takes the respondent to a secure online survey tool from where he/she can take the survey or fill in the survey questionnaire. Being a cost-efficient, quicker, and having a wider reach, web-based surveys are more preferred by the researchers. The primary benefit of a web-based questionnaire is flexibility. Respondents are free to take the survey in their free time using either a desktop, laptop, tablet, or mobile.

- Mail Questionnaire : In a mail questionnaire, the survey is mailed out to a host of the sample population, enabling the researcher to connect with a wide range of audiences. The mail questionnaire typically consists of a packet containing a cover sheet that introduces the audience about the type of research and reason why it is being conducted along with a prepaid return to collect data online. Although the mail questionnaire has a higher churn rate compared to other quantitative data collection methods, adding certain perks such as reminders and incentives to complete the survey help in drastically improving the churn rate. One of the major benefits of the mail questionnaire is all the responses are anonymous, and respondents are allowed to take as much time as they want to complete the survey and be completely honest about the answer without the fear of prejudice.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

As the name suggests, it is a pretty simple and straightforward method of collecting quantitative data. In this method, researchers collect quantitative data through systematic observations by using techniques like counting the number of people present at the specific event at a particular time and a particular venue or number of people attending the event in a designated place. More often, for quantitative data collection, the researchers have a naturalistic observation approach. It needs keen observation skills and senses for getting the numerical data about the “what” and not about “why” and ”how.”

Naturalistic observation is used to collect both types of data; qualitative and quantitative. However, structured observation is more used to collect quantitative rather than qualitative data collection .

- Structured observation: In this type of observation method, the researcher has to make careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a more comprehensive or structured setting compared to naturalistic or participant observation . In a structured observation, the researchers, rather than observing everything, focus only on very specific behaviors of interest. It allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. When the qualitative observations require a judgment on the part of the observers – it is often described as coding, which requires a clearly defining a set of target behaviors.

Document review is a process used to collect data after reviewing the existing documents. It is an efficient and effective way of gathering data as documents are manageable. Those are the practical resource to get qualified data from the past. Apart from strengthening and supporting the research by providing supplementary research data document review has emerged as one of the beneficial methods to gather quantitative research data.

Three primary document types are being analyzed for collecting supporting quantitative research data.

- Public Records: Under this document review, official, ongoing records of an organization are analyzed for further research. For example, annual reports policy manuals, student activities, game activities in the university, etc.

- Personal Documents: In contrast to public documents, this type of document review deals with individual personal accounts of individuals’ actions, behavior, health, physique, etc. For example, the height and weight of the students, distance students are traveling to attend the school, etc.

- Physical Evidence: Physical evidence or physical documents deal with previous achievements of an individual or of an organization in terms of monetary and scalable growth.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Quantitative data is not about convergent reasoning, but it is about divergent thinking. It deals with the numerical, logic, and an objective stance, by focusing on numeric and unchanging data. More often, data collection methods are used to collect quantitative research data, and the results are dependent on the larger sample sizes that are commonly representing the population researcher intend to study.

Although there are many other methods to collect quantitative data. Those mentioned above probability sampling, interviews, questionnaire observation, and document review are the most common and widely used methods for data collection.

With QuestionPro, you can precise results, and data analysis . QuestionPro provides the opportunity to collect data from a large number of participants. It increases the representativeness of the sample and providing more accurate results.

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

The Power of AI in Customer Experience — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Apr 16, 2024

Employee Lifecycle Management Software: Top of 2024

Apr 15, 2024

Top 15 Sentiment Analysis Software That Should Be on Your List

Top 13 A/B Testing Software for Optimizing Your Website

Apr 12, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Qualitative Data Collection and Quantitative Data Collection

- Published: January 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Practitioner/scholars often use more than one type of data collection in order to provide a robust answer to a research problem or question. At times, practitioner–researchers will have very specific quantitative questions, and they will also create additional research questions (utilizing qualitative data collection methods) in order to provide a more well-rounded answer to an overarching research problem or question. This chapter 4 discusses the practical issues of data collection methods. It shows how a study’s research questions should be the driving force behind the choice of data collection methods, and it explains the utility/supportive nature of a variety of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods resources. Vignettes of practice in using diverse data collection methods are included.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari .

Data collection is a systematic process of gathering observations or measurements. Whether you are performing research for business, governmental, or academic purposes, data collection allows you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem .

While methods and aims may differ between fields, the overall process of data collection remains largely the same. Before you begin collecting data, you need to consider:

- The aim of the research

- The type of data that you will collect

- The methods and procedures you will use to collect, store, and process the data

To collect high-quality data that is relevant to your purposes, follow these four steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: define the aim of your research, step 2: choose your data collection method, step 3: plan your data collection procedures, step 4: collect the data, frequently asked questions about data collection.

Before you start the process of data collection, you need to identify exactly what you want to achieve. You can start by writing a problem statement : what is the practical or scientific issue that you want to address, and why does it matter?

Next, formulate one or more research questions that precisely define what you want to find out. Depending on your research questions, you might need to collect quantitative or qualitative data :

- Quantitative data is expressed in numbers and graphs and is analysed through statistical methods .

- Qualitative data is expressed in words and analysed through interpretations and categorisations.

If your aim is to test a hypothesis , measure something precisely, or gain large-scale statistical insights, collect quantitative data. If your aim is to explore ideas, understand experiences, or gain detailed insights into a specific context, collect qualitative data.

If you have several aims, you can use a mixed methods approach that collects both types of data.

- Your first aim is to assess whether there are significant differences in perceptions of managers across different departments and office locations.

- Your second aim is to gather meaningful feedback from employees to explore new ideas for how managers can improve.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Based on the data you want to collect, decide which method is best suited for your research.

- Experimental research is primarily a quantitative method.

- Interviews , focus groups , and ethnographies are qualitative methods.

- Surveys , observations, archival research, and secondary data collection can be quantitative or qualitative methods.

Carefully consider what method you will use to gather data that helps you directly answer your research questions.

When you know which method(s) you are using, you need to plan exactly how you will implement them. What procedures will you follow to make accurate observations or measurements of the variables you are interested in?

For instance, if you’re conducting surveys or interviews, decide what form the questions will take; if you’re conducting an experiment, make decisions about your experimental design .

Operationalisation

Sometimes your variables can be measured directly: for example, you can collect data on the average age of employees simply by asking for dates of birth. However, often you’ll be interested in collecting data on more abstract concepts or variables that can’t be directly observed.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations. When planning how you will collect data, you need to translate the conceptual definition of what you want to study into the operational definition of what you will actually measure.

- You ask managers to rate their own leadership skills on 5-point scales assessing the ability to delegate, decisiveness, and dependability.

- You ask their direct employees to provide anonymous feedback on the managers regarding the same topics.

You may need to develop a sampling plan to obtain data systematically. This involves defining a population , the group you want to draw conclusions about, and a sample, the group you will actually collect data from.

Your sampling method will determine how you recruit participants or obtain measurements for your study. To decide on a sampling method you will need to consider factors like the required sample size, accessibility of the sample, and time frame of the data collection.

Standardising procedures

If multiple researchers are involved, write a detailed manual to standardise data collection procedures in your study.

This means laying out specific step-by-step instructions so that everyone in your research team collects data in a consistent way – for example, by conducting experiments under the same conditions and using objective criteria to record and categorise observations.

This helps ensure the reliability of your data, and you can also use it to replicate the study in the future.

Creating a data management plan

Before beginning data collection, you should also decide how you will organise and store your data.

- If you are collecting data from people, you will likely need to anonymise and safeguard the data to prevent leaks of sensitive information (e.g. names or identity numbers).

- If you are collecting data via interviews or pencil-and-paper formats, you will need to perform transcriptions or data entry in systematic ways to minimise distortion.

- You can prevent loss of data by having an organisation system that is routinely backed up.

Finally, you can implement your chosen methods to measure or observe the variables you are interested in.

The closed-ended questions ask participants to rate their manager’s leadership skills on scales from 1 to 5. The data produced is numerical and can be statistically analysed for averages and patterns.

To ensure that high-quality data is recorded in a systematic way, here are some best practices:

- Record all relevant information as and when you obtain data. For example, note down whether or how lab equipment is recalibrated during an experimental study.

- Double-check manual data entry for errors.

- If you collect quantitative data, you can assess the reliability and validity to get an indication of your data quality.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

When conducting research, collecting original data has significant advantages:

- You can tailor data collection to your specific research aims (e.g., understanding the needs of your consumers or user testing your website).

- You can control and standardise the process for high reliability and validity (e.g., choosing appropriate measurements and sampling methods ).

However, there are also some drawbacks: data collection can be time-consuming, labour-intensive, and expensive. In some cases, it’s more efficient to use secondary data that has already been collected by someone else, but the data might be less reliable.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research , you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, May 04). Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/data-collection-guide/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, triangulation in research | guide, types, examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples.

- A/B Monadic Test

- A/B Pre-Roll Test

- Key Driver Analysis

- Multiple Implicit

- Penalty Reward

- Price Sensitivity

- Segmentation

- Single Implicit

- Category Exploration

- Competitive Landscape

- Consumer Segmentation

- Innovation & Renovation

- Product Portfolio

- Marketing Creatives

- Advertising

- Shelf Optimization

- Performance Monitoring

- Better Brand Health Tracking

- Ad Tracking

- Trend Tracking

- Satisfaction Tracking

- AI Insights

- Case Studies

quantilope is the Consumer Intelligence Platform for all end-to-end research needs

5 Methods of Data Collection for Quantitative Research

In this blog, read up on five different data collection techniques for quantitative research studies.

Quantitative research forms the basis for many business decisions. But what is quantitative data collection, why is it important, and which data collection methods are used in quantitative research?

Table of Contents:

- What is quantitative data collection?

- The importance of quantitative data collection

- Methods used for quantitative data collection

- Example of a survey showing quantitative data

- Strengths and weaknesses of quantitative data

What is quantitative data collection?

Quantitative data collection is the gathering of numeric data that puts consumer insights into a quantifiable context. It typically involves a large number of respondents - large enough to extract statistically reliable findings that can be extrapolated to a larger population.

The actual data collection process for quantitative findings is typically done using a quantitative online questionnaire that asks respondents yes/no questions, ranking scales, rating matrices, and other quantitative question types. With these results, researchers can generate data charts to summarize the quantitative findings and generate easily digestible key takeaways.

Back to Table of Contents

The importance of quantitative data collection

Quantitative data collection can confirm or deny a brand's hypothesis, guide product development, tailor marketing materials, and much more. It provides brands with reliable information to make decisions off of (i.e. 86% like lemon-lime flavor or just 12% are interested in a cinnamon-scented hand soap).

Compared to qualitative data collection, quantitative data allows for comparison between insights given higher base sizes which leads to the ability to have statistical significance. Brands can cut and analyze their dataset in a variety of ways, looking at their findings among different demographic groups, behavioral groups, and other ways of interest. It's also generally easier and quicker to collect quantitative data than it is to gather qualitative feedback, making it an important data collection tool for brands that need quick, reliable, concrete insights.

In order to make justified business decisions from quantitative data, brands need to recruit a high-quality sample that's reflective of their true target market (one that's comprised of all ages/genders rather than an isolated group). For example, a study into usage and attitudes around orange juice might include consumers who buy and/or drink orange juice at a certain frequency or who buy a variety of orange juice brands from different outlets.

Methods used for quantitative data collection

So knowing what quantitative data collection is and why it's important , how does one go about researching a large, high-quality, representative sample ?

Below are five examples of how to conduct your study through various data collection methods :

Online quantitative surveys

Online surveys are a common and effective way of collecting data from a large number of people. They tend to be made up of closed-ended questions so that responses across the sample are comparable; however, a small number of open-ended questions can be included as well (i.e. questions that require a written response rather than a selection of answers in a close-ended list). Open-ended questions are helpful to gather actual language used by respondents on a certain issue or to collect feedback on a view that might not be shown in a set list of responses).

Online surveys are quick and easy to send out, typically done so through survey panels. They can also appear in pop-ups on websites or via a link embedded in social media. From the participant’s point of view, online surveys are convenient to complete and submit, using whichever device they prefer (mobile phone, tablet, or computer). Anonymity is also viewed as a positive: online survey software ensures respondents’ identities are kept completely confidential.

To gather respondents for online surveys, researchers have several options. Probability sampling is one route, where respondents are selected using a random selection method. As such, everyone within the population has an equal chance of getting selected to participate.

There are four common types of probability sampling .

- Simple random sampling is the most straightforward approach, which involves randomly selecting individuals from the population without any specific criteria or grouping.

- Stratified random sampling divides the population into subgroups (strata) and selects a random sample from each stratum. This is useful when a population includes subgroups that you want to be sure you cover in your research.

- Cluster sampling divides the population into clusters and then randomly selects some of the clusters to sample in their entirety. This is useful when a population is geographically dispersed and it would be impossible to include everyone.

- Systematic sampling begins with a random starting point and then selects every nth member of the population after that point (i.e. every 15th respondent).

Learn how to leverage AI to help generate your online quantitative survey inputs:

While online surveys are by far the most common way to collect quantitative data in today’s modern age, there are still some harder-to-reach respondents where other mediums can be beneficial; for example, those who aren’t tech-savvy or who don’t have a stable internet connection. For these audiences, offline surveys may be needed.

Offline quantitative surveys

Offline surveys (though much rarer to come across these days) are a way of gathering respondent feedback without digital means. This could be something like postal questionnaires that are sent out to a sample population and asked to return the questionnaire by mail (like the Census) or telephone surveys where questions are asked of respondents over the phone.

Offline surveys certainly take longer to collect data than online surveys and they can become expensive if the population is difficult to reach (requiring a higher incentive). As with online surveys, anonymity is protected, assuming the mail is not intercepted or lost.

Despite the major difference in data collection to an online survey approach, offline survey data is still reported on in an aggregated, numeric fashion.

In-person interviews are another popular way of researching or polling a population. They can be thought of as a survey but in a verbal, in-person, or virtual face-to-face format. The online format of interviews is becoming more popular nowadays, as it is cheaper and logistically easier to organize than in-person face-to-face interviews, yet still allows the interviewer to see and hear from the respondent in their own words.

Though many interviews are collected for qualitative research, interviews can also be leveraged quantitatively; like a phone survey, an interviewer runs through a survey with the respondent, asking mainly closed-ended questions (yes/no, multiple choice questions, or questions with rating scales that ask how strongly the respondent agrees with statements). The advantage of structured interviews is that the interviewer can pace the survey, making sure the respondent gives enough consideration to each question. It also adds a human touch, which can be more engaging for some respondents. On the other hand, for more sensitive issues, respondents may feel more inclined to complete a survey online for a greater sense of anonymity - so it all depends on your research questions, the survey topic, and the audience you're researching.

Observations

Observation studies in quantitative research are similar in nature to a qualitative ethnographic study (in which a researcher also observes consumers in their natural habitats), yet observation studies for quant research remain focused on the numbers - how many people do an action, how much of a product consumer pick up, etc.

For quantitative observations, researchers will record the number and types of people who do a certain action - such as choosing a specific product from a grocery shelf, speaking to a company representative at an event, or how many people pass through a certain area within a given timeframe. Observation studies are generally structured, with the observer asked to note behavior using set parameters. Structured observation means that the observer has to hone in on very specific behaviors, which can be quite nuanced. This requires the observer to use his/her own judgment about what type of behavior is being exhibited (e.g. reading labels on products before selecting them; considering different items before making the final choice; making a selection based on price).

Document reviews and secondary data sources

A fifth method of data collection for quantitative research is known as secondary research : reviewing existing research to see how it can contribute to understanding a new issue in question. This is in contrast to the primary research methods above, which is research that is specially commissioned and carried out for a research project.

There are numerous secondary data sources that researchers can analyze such as public records, government research, company databases, existing reports, paid-for research publications, magazines, journals, case studies, websites, books, and more.

Aside from using secondary research alone, secondary research documents can also be used in anticipation of primary research, to understand which knowledge gaps need to be filled and to nail down the issues that might be important to explore further in a primary research study. Back to Table of Contents

Example of a survey showing quantitative data

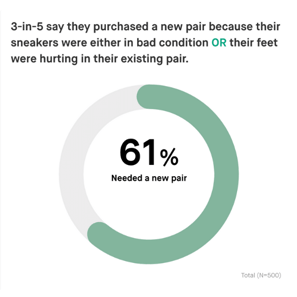

The below study shows what quantitative data might look like in a final study dashboard, taken from quantilope's Sneaker category insights study .

The study includes a variety of usage and attitude metrics around sneaker wear, sneaker purchases, seasonality of sneakers, and more. Check out some of the data charts below showing these quantitative data findings - the first of which even cuts the quantitative data findings by demographics.

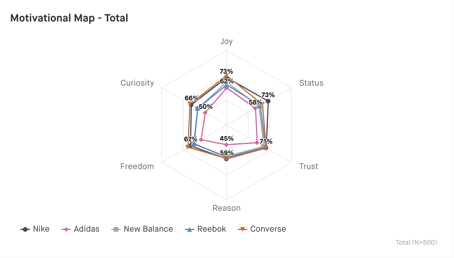

Beyond these basic usage and attitude (or, descriptive) data metrics, quantitative data also includes advanced methods - such as implicit association testing. See what these quantitative data charts look like from the same sneaker study below:

These are just a few examples of how a researcher or insights team might show their quantitative data findings. However, there are many ways to visualize quantitative data in an insights study, from bar charts, column charts, pie charts, donut charts, spider charts, and more, depending on what best suits the story your data is telling. Back to Table of Contents

Strengths and weaknesses of quantitative data collection

quantitative data is a great way to capture informative insights about your brand, product, category, or competitors. It's relatively quick, depending on your sample audience, and more affordable than other data collection methods such as qualitative focus groups. With quantitative panels, it's easy to access nearly any audience you might need - from something as general as the US population to something as specific as cannabis users . There are many ways to visualize quantitative findings, making it a customizable form of insights - whether you want to show the data in a bar chart, pie chart, etc.

For those looking for quick, affordable, actionable insights, quantitative studies are the way to go.

quantitative data collection, despite the many benefits outlined above, might also not be the right fit for your exact needs. For example, you often don't get as detailed and in-depth answers quantitatively as you would with an in-person interview, focus group, or ethnographic observation (all forms of qualitative research). When running a quantitative survey, it’s best practice to review your data for quality measures to ensure all respondents are ones you want to keep in your data set. Fortunately, there are a lot of precautions research providers can take to navigate these obstacles - such as automated data cleaners and data flags. Of course, the first step to ensuring high-quality results is to use a trusted panel provider. Back to Table of Contents

Quantitative research typically needs to undergo statistical analysis for it to be useful and actionable to any business. It is therefore crucial that the method of data collection, sample size, and sample criteria are considered in light of the research questions asked.

quantilope’s online platform is ideal for quantitative research studies. The online format means a large sample can be reached easily and quickly through connected respondent panels that effectively reach the desired target audience. Response rates are high, as respondents can take their survey from anywhere, using any device with internet access.

Surveys are easy to build with quantilope’s online survey builder. Simply choose questions to include from pre-designed survey templates or build your own questions using the platform’s drag & drop functionality (of which both options are fully customizable). Once the survey is live, findings update in real-time so that brands can get an idea of consumer attitudes long before the survey is complete. In addition to basic usage and attitude questions, quantilope’s suite of advanced research methodologies provides an AI-driven approach to many types of research questions. These range from exploring the features of products that drive purchase through a Key Driver Analysis , compiling the ideal portfolio of products using a TURF , or identifying the optimal price point for a product or service using a Price Sensitivity Meter (PSM) .

Depending on the type of data sought it might be worth considering a mixed-method approach, including both qual and quant in a single research study. Alongside quantitative online surveys, quantilope’s video research solution - inColor , offers qualitative research in the form of videoed responses to survey questions. inColor’s qualitative data analysis includes an AI-drive read on respondent sentiment, keyword trends, and facial expressions.

To find out more about how quantilope can help with any aspect of your research design and to start conducting high-quality, quantitative research, get in touch below:

Get in touch to learn more about quantitative research studies!

Related posts, what are brand perceptions and how can you measure them, how can brands build, measure, and manage brand equity, how to use a brand insights tool to improve your branding strategy, quantilope's 5th consecutive year as a 'fastest growing tech company'.

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Data Mining — Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods

- Categories: Data Mining Information Age

About this sample

Words: 838 |

Published: Aug 16, 2019

Words: 838 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1802 words

2 pages / 985 words

1 pages / 594 words

3 pages / 1146 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Data Mining

Databases play a critical role in managing and organizing large amounts of information, making them an essential tool in various fields. This essay aims to highlight the importance of databases in managing and organizing large [...]

Podcasting is the process of capturing and posting an audio event in digital sound object online. The word podcast was primarily formed as an amalgam of ‘iPod’ and ‘broadcast’, so that can give one a general idea of the nature. [...]

Internet of everything is when people, process and data is brought together so that networked connections are made, and so the connections are more relevant and valuable. It creates more capabilities and can help an economy with [...]

Ahmad Aldhafiri CEGR 4802/1/2018 GISA geographic information system (GIS) is a system designed to capture, store, manipulate, analyze, manage, and present all types of geographic data. The key word to this technology is [...]

Regardless of the criticalness of having the preferred standpoint and wonderful information in a relationship, there is with everything considered a general endorsement in the made work that low-quality information is an issue [...]

The paper will first define and describe what is data mining. It will also seek to determine why data mining is useful and show that data mining is concerned with the analysis of data and the use of techniques for finding [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Qualitative v. Quantitative Research Reflection

Initially, after learning, reading, and researching about these to methods of approaching research in the social work field, I found myself immediately drawn towards quantitative research. Numbers make sense to me and it seems incredibly logical and convenient in theory for me to be able to reduce the human experience into a data set of numbers which I can then calculate and compute to give me a meaningful answer. However, it’s become clear to me over these past few weeks through studying and reading more qualitative studies, that they can be an incredibly valuable resource to actually understanding with and sympathizing with the material we are researching. I believe that qualitative research gives the researcher as well as the person applying the conclusions reached from the research into practice a good understanding of the human component and nuances that go into implementing interventions. Often, it seems that qualitative research can explore the complexities a little more delicately than quantitative research might be able to because the data is becoming synthesized into numbers. Qualitative research does have it’s downfalls though. While all forms of research is subject to various biases, it would seem that qualitative research has a higher risk because, instead of interpreting numbers and calculations, we must interpret human thoughts, feelings, and experiences, which are much less concrete variables. It also may be harder to reach a definitive, mathematically supported answer to the question being posed. Ultimately, I believe mixed methods approach could take the advantages of both methods and combine them so that the research covers both the concrete evidence presented through quantitative researched with the complex insight of the qualitative research.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- JMIR Form Res

- v.6(4); 2022 Apr

The Strategies for Quantitative and Qualitative Remote Data Collection: Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic

Keenae tiersma.

1 Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

2 Department of Psychiatric Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Mira Reichman

3 Integrated Brain Health Clinical and Research Program, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Paula J Popok

Maura barry, a rani elwy.

4 Implementation Science Core, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, RI, United States

5 Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, VA Bedford Healthcare System, Bedford, MA, United States

Efrén J Flores

Kelly e irwin, ana-maria vranceanu.

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a rapid shift to web-based or blended design models for both ongoing and future clinical research activities. Research conducted virtually not only has the potential to increase the patient-centeredness of clinical research but may also further widen existing disparities in research participation among underrepresented individuals. In this viewpoint, we discuss practical strategies for quantitative and qualitative remote research data collection based on previous literature and our own ongoing clinical research to overcome challenges presented by the shift to remote data collection. We aim to contribute to and catalyze the dissemination of best practices related to remote data collection methodologies to address the opportunities presented by this shift and develop strategies for inclusive research.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is transforming the landscape of clinical research. The pandemic has necessitated the unexpected adaptation of ongoing clinical research activities to web-based or blended design (ie, part web-based, part in-person) models [ 1 ] and has rapidly accelerated a shift within clinical research toward web-based study designs. Despite the high levels of patient and health care provider satisfaction with telemedicine and virtually conducted clinical research [ 2 , 3 ], many challenges exist to the web-based conduct of rigorous, efficient, and patient-centered clinical research, particularly related to the engagement of diverse and marginalized populations [ 4 ]. The aim of this paper is to discuss practical strategies to guide researchers in the remote collection of quantitative and qualitative data, derived from both previous literature and our own ongoing clinical research.

Many health care providers and clinical researchers have marveled at the way the COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the widespread adoption and expansion of telemedicine, seemingly overnight [ 5 , 6 ]. Despite the sluggish adoption of telemedicine observed in academic medical centers over the past several decades [ 7 , 8 ], the pandemic has spurred rapid changes in public and organizational policy regulating telemedicine in the United States, facilitating a tipping point toward the web-based provision of both health care and conduct of clinical research [ 1 , 2 , 5 , 6 ]. Enabled by fast-tracked institutional review board policies and amendments [ 1 ], researchers have adapted clinical research study procedures in innovative ways: engaging in web-based outreach for study recruitment, collecting electronic informed consent, conducting study visits, delivering interventions over the phone or live video, and using remote methods to collect data [ 1 ]. Several studies have reported high satisfaction of both providers and patients with the use of telemedicine during COVID-19 and a willingness to continue using telemedicine after the pandemic, including for clinical research [ 2 , 3 ].