ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Academic performance in adolescent students: the role of parenting styles and socio-demographic factors – a cross sectional study from peshawar, pakistan.

- 1 Institute of Public Health & Social Sciences, Khyber Medical University, Peshawar, Pakistan

- 2 Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

Academic performance is among the several components of academic success. Many factors, including socioeconomic status, student temperament and motivation, peer, and parental support influence academic performance. Our study aims to investigate the determinants of academic performance with emphasis on the role of parental styles in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. A total of 456 students from 4 public and 4 private schools were interviewed. Academic performance was assessed based on self-reported grades in the latest internal examinations. Parenting styles were assessed through the administration of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI). Regression analysis was conducted to assess the influence of socio-demographic factors and parenting styles on academic performance. Factors associated with and differences between “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers were analyzed. Higher socio-economic status, father’s education level, and higher care scores were independently associated with better academic performance in adolescent students. Affectionless control was the most common parenting style for fathers and mothers. When adapted by the father, it was also the only parenting style independently improving academic performance. Overall, mean “care” scores were higher for mothers and mean “overprotection” scores were higher for fathers. Parenting workshops and school activities emphasizing the involvement of mothers and fathers in the parenting of adolescent students might have a positive influence on their academic performance. Affectionless control may be associated with improved academics but the emotional and psychosocial effects of this style of parenting need to be investigated before recommendations are made.

Introduction

Despite residual ambiguity in the term, definitions over time have identified several elements of “academic success” ( Kuh et al., 2006 ; York et al., 2015 ). Used interchangeably with “student success,” it encompasses academic achievement, attainment of learning objectives, acquisition of desired skills and competencies, satisfaction, persistence, and post-college performance ( Kuh et al., 2006 ; York et al., 2015 ). Linked to happiness in undergraduate students ( Flynn and MacLeod, 2015 ) and low health risk behavior in adolescents ( Hawkins, 1997 ), a vast amount of literature is available on the determinants of academic success. Studies have shown socioeconomic characteristics ( Vacha and McLaughlin, 1992 ; Ginsburg and Bronstein, 1993 ; Chow, 2000 ; McClelland et al., 2000 ; Tomul and Savasci, 2012 ), student characteristics including temperament, motivation and resilience ( Ginsburg and Bronstein, 1993 ; Linnenbrink and Pintrich, 2002 ; Farsides and Woodfield, 2003 ; Valiente et al., 2007 ; Beauvais et al., 2014 ) and peer ( Dennis et al., 2005 ), and parental support ( Cutrona et al., 1994 ; Sanders, 1998 ; Dennis et al., 2005 ; Bean et al., 2006 ) to have a bearing on academic performance in students.

The influence of parenting styles and parental involvement is particularly in focus when assessing determinants of academic success in adolescent children ( Shute et al., 2011 ; Rahimpour et al., 2015 ; Weis et al., 2016 ; Checa and Abundis-Gutierrez, 2017 ; Zhang et al., 2019 ). The influence may be of significance from infancy through adulthood ( Steinberg et al., 1989 ; Weiss and Schwarz, 1996 ; Zahedani et al., 2016 ) and can be appreciated across a range of ethnicities ( Desimone, 1999 ; Battle, 2002 ; Jeynes, 2007 ). Previously, the authoritative parenting style has been most frequently associated with better academic performance among adolescent students ( Steinberg et al., 1989 , 1992 ; Deslandes et al., 1997 , 1998 ; Aunola et al., 2000 ; Adeyemo, 2005 ; Checa et al., 2019 ), while purely restrictive and negligent styles have shown to have a negative influence on academic performance ( Hillstrom, 2009 ; Parsasirat et al., 2013 ; Osorio and González-Cámara, 2016 ). Parenting styles have also been linked to academic performance indirectly through regulation of emotion, self-expression ( Deslandes et al., 1997 ; Weis et al., 2016 ), and self-esteem ( Zakeri and Karimpour, 2011 ).

Significant efforts have been made to explore and integrate factors which influence parenting stress and behaviors ( Belsky, 1984 ; Abidin, 1992 ; Östberg and Hagekull, 2000 ). A number of factors, including parent personality and psychopathology (in terms of extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, depression and emotional stability), parenting beliefs, parent-child relationship, marital satisfaction, parenting style of spouse, work stress, child characteristics, education level, and socioeconomic status have been highlighted for their role in determining parenting styles ( Belsky, 1984 ; Simons et al., 1990 , 1993 ; Bluestone and Tamis-LeMonda, 1999 ; Huver et al., 2010 ; Smith, 2010 ; McCabe, 2014 ). Studies have also highlighted differences between fathers and mothers in how these factors influence them ( Simons et al., 1990 ; Ponnet et al., 2013 ).

Insight into determinants of academic success and the role of parenting styles can have significant impact on policy recommendations. However, most existing data comes from western cultures where individualistic themes predominate. While some studies highlight differences between the two ( Wang and Leichtman, 2000 ), evidence from eastern collectivist cultures, including Pakistan, is scarce ( Masud et al., 2015 ; Khalid et al., 2018 ).

The aim of this study is to identify the determinants of academic performance, including the influence of parenting styles, in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. We also aim to investigate the factors affecting parenting styles and the differences between parenting behaviors of father and mothers.

Materials and Methods

The manuscript has been reported in concordance with the STROBE checklist ( Vandenbroucke et al., 2014 ).

Study Design

A cross sectional study was conducted by interviewing school-going students (grades 8, 9, and 10) to assess determinants of academic grades including the influence of parenting styles.

The study took place in the city of Peshawar in Pakistan at eight schools, four from the public sector and four from the private sector. The data collection process began in January 2017 concluded in December 2017.

The prevalence of high grades (A and A plus) among adolescent students was between 42.6 and 57.4% in a previous study ( Cohen and Rice, 1997 #248). Based on this, a sample size of 376 students was calculated to study the determinants of high grades in adolescent students with a confidence level of 95%. Assuming a non-response rate of approximately 20%, we decided to target 500 students from four public and four private schools. A total of 456 students participated in our study.

Participants

Inclusion criteria.

From the eight schools which provided admin consent to conduct the study, students enrolled in grade 8, 9, or 10 were invited to take part in the study. Following consent from the parents and assent from the student, he or she was included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Any student unable to understand or fill out the interview pro forma or questionnaire independently.

Data Sources and Measurement

Data was collected through a one on one interaction between each student and the data collector individually. The following tools were used.

Demographic pro forma ( Supplementary Datasheet 1 )

A brief and simple pro forma was structured to address all demographic related variables needed for the study.

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) ( Supplementary Datasheet 2 )

The original version of the Parental Bonding Instrument ( Parker et al., 1979 ), previously validated for internal consistency, convergent validity, satisfactory construct, and independence from mood effects in several different populations, including Turkish and Chinese ( Parker et al., 1979 ; Parker, 1983 , 1990 ; Cavedo and Parker, 1994 ; Dudley and Wisbey, 2000 ; Wilhelm et al., 2005 ; Murphy et al., 2010 ; Liu et al., 2011 ; Behzadi and Parker, 2015 ), was employed in our study. This tool, composed of 25 questions, assesses parenting styles as two independent measures of “care” and “control” as perceived by the child. It is filled out separately for the father and the mother. It is available online for use without copyright. The use of PBI has been validated for British Pakistanis ( Mujtaba and Furnham, 2001 ) and Pakistani women ( Qadir et al., 2005 ). A paper by Qadir et al. on the validity of PBI for Pakistani women, reports the Cronbach alpha scores to be 0.91 and 0.80 for the “care” and “overprotection” scales, respectively ( Qadir et al., 2005 ).

The demographic pro forma and the parental bonding index were translated into Urdu by an individual fluent in both languages and validated with the help of an epidemiologist and two experts in the field ( Supplementary Datasheet 3 ). Pilot testing of translated versions was done with 20 students to ensure clarity and assess understanding and comprehension by the students. Both versions for the two tools were provided in hard copy to each student to fill out whichever one he/she preferred. The data collector first verbally explained the items on the demographic pro forma and the PBI to the student following which the student was allowed to fill it out independently.

Using the data sources mentioned above, data was collected for the following variables.

Student Related

Gender, type of school (public or private), class grade (8th, 9th, and 10th) and academic performance.

In Pakistan, public and private schools may differ in several aspects including fee structures, class strength and difficulty levels of internal examinations, with private schools being more expensive, with fewer students per classroom, and subjectively tougher internal examinations.

The academic performance was judged as the overall grade (a combination of all subjects including English, Mathematics and Science) in the latest internal examinations sat by the student as A+, A, B, C, or D.

Family Related

Family structure and type of accommodation (rented or owned).

Parent Related

Information on living status, education level, employment status, employment type and parenting styles was obtained from the student separately for the father and mother.

Quantitative Variables

Academic performance.

The grades A+, A were categorized as “high” grades and grades B, C, and D were categorized as “low” grades.

Socio-Economic Status

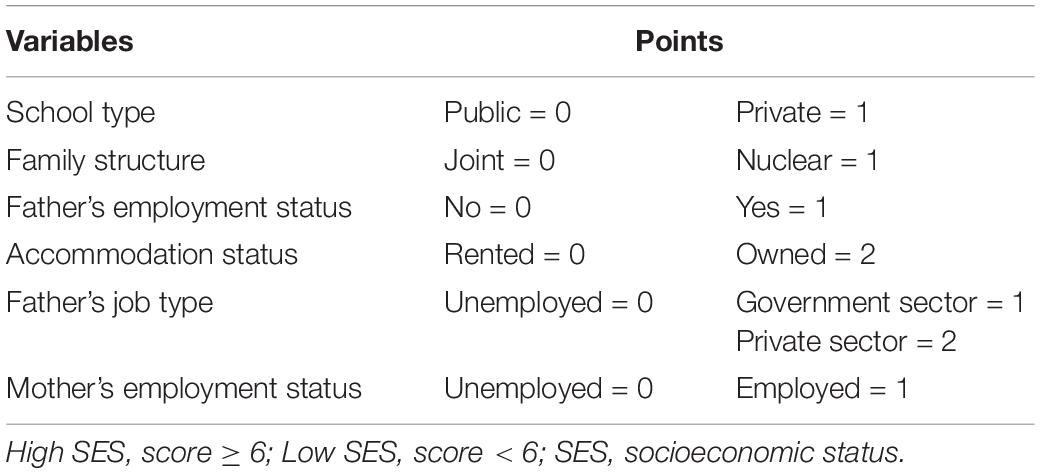

We used variables which adolescent students are expected to have knowledge of to calculate a score which categorized students as belonging to either a high or low socioeconomic status. The points assigned to each variable are show in Table 1 .

Table 1. Calculation of an estimated socioeconomic status.

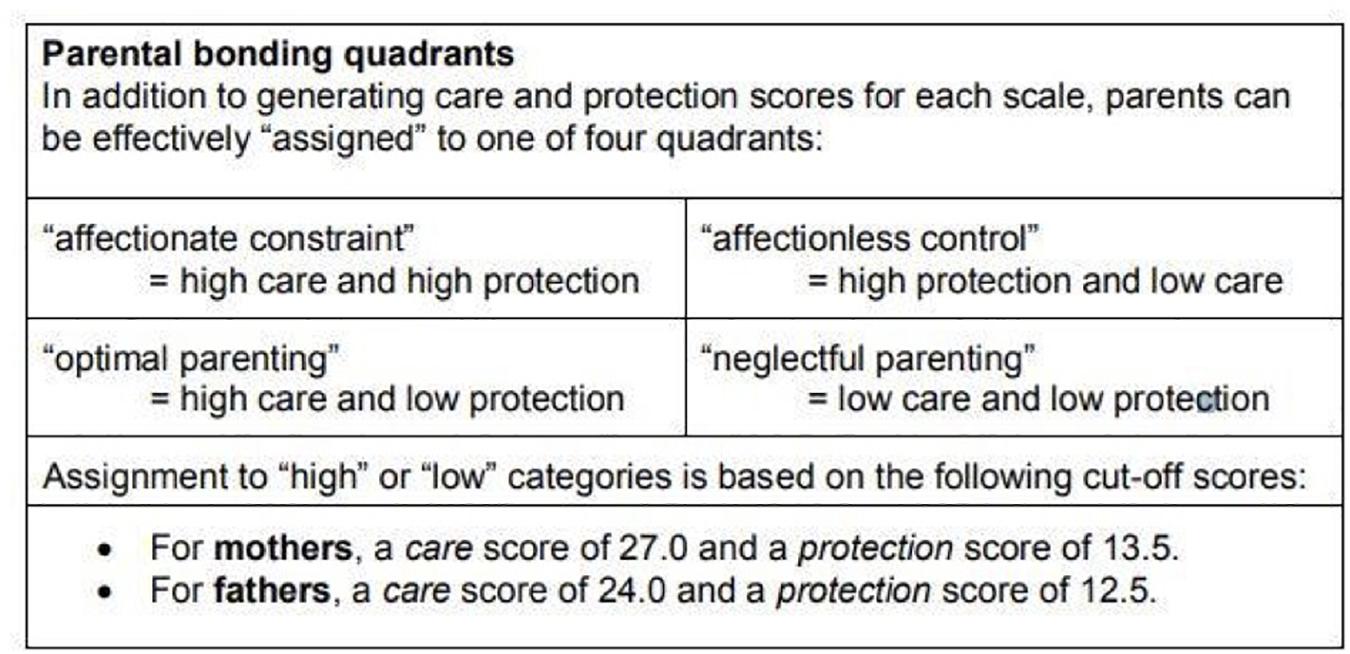

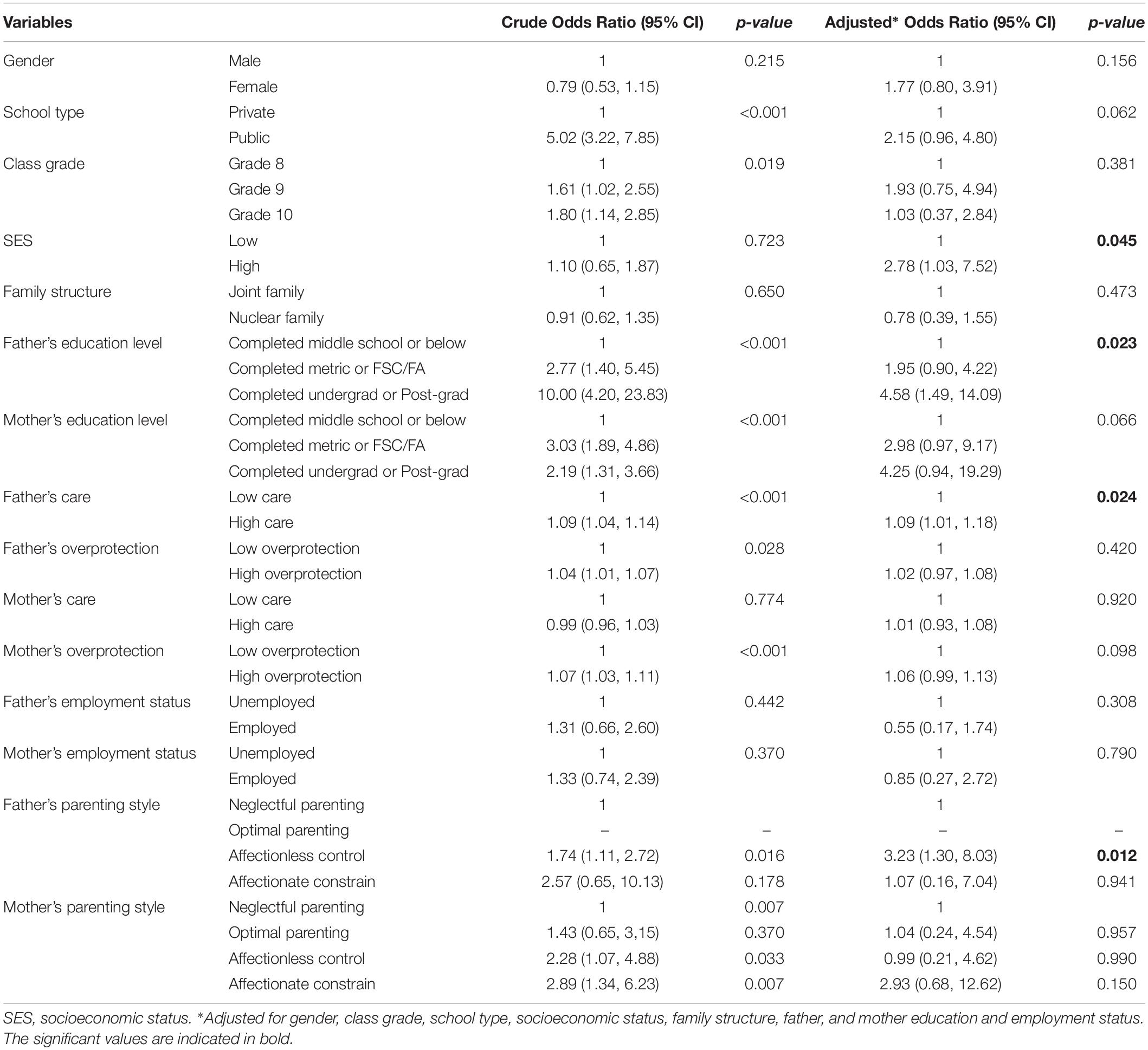

Parenting Styles

The PBI is a 25 item questionnaire, with 12 items measuring “care” and 13 items measuring “overprotection.” All responses have a 4 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very unlikely) to 3 (very likely). The responses are summed up to categorize each parent to exhibit low or high “care” and low or high “overprotection.” Based on these findings, each parent can then be put into one of the 4 quadrants representing parenting styles including “affectionate constraint,” “affectionless control,” “optimal parenting,” and “neglectful parenting.” This computation is explained in Figure 1 obtained from the information provided with the PBI ( Parker et al., 1979 ).

Figure 1. Assigining parenting styles using the PBI ( Parker, 1979 #192).

Students were allowed to fill in the pro forma and questionnaire independently to avoid bias during the data collection process. However, self-reporting of grades in latest examination may be subject to recall bias.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive analyses were conducted on all study variables including socio-demographic factors and parenting styles. Categorical variables were reported as proportions and continuous variables as measures of central tendency. All continuous variables were subjected to a normality test. Mean and median values were reported for variables with normally distributed and skewed data, respectively.

The summary t -test was used to study the differences between mean “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers. The independent sample t -test was used to study the factors associated with “care” and “overprotection” scores of fathers and mothers. Threshold for significance was p = 0.05.

The determinants of high grades including the influence of parenting styles were assessed using regression analysis. The outcome variable, student grades, was treated as binary (high grades and low grades). The threshold for statistical significance was p = 0.05. Crude Odds Ratios were adjusted for gender, school type, socioeconomic status, family structure, class grade, parents’ employments and education status.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Khyber Medical University, Advance Studies and Research Board (KMU-AS&RB) in August 2016. Identifying information of students was not obtained. Permissions were obtained from the relevant authorities in the school administration before approaching the students and their parents. Written consent was obtained from the parents through the home-work diary of the students and verbal assent of each student was obtained.

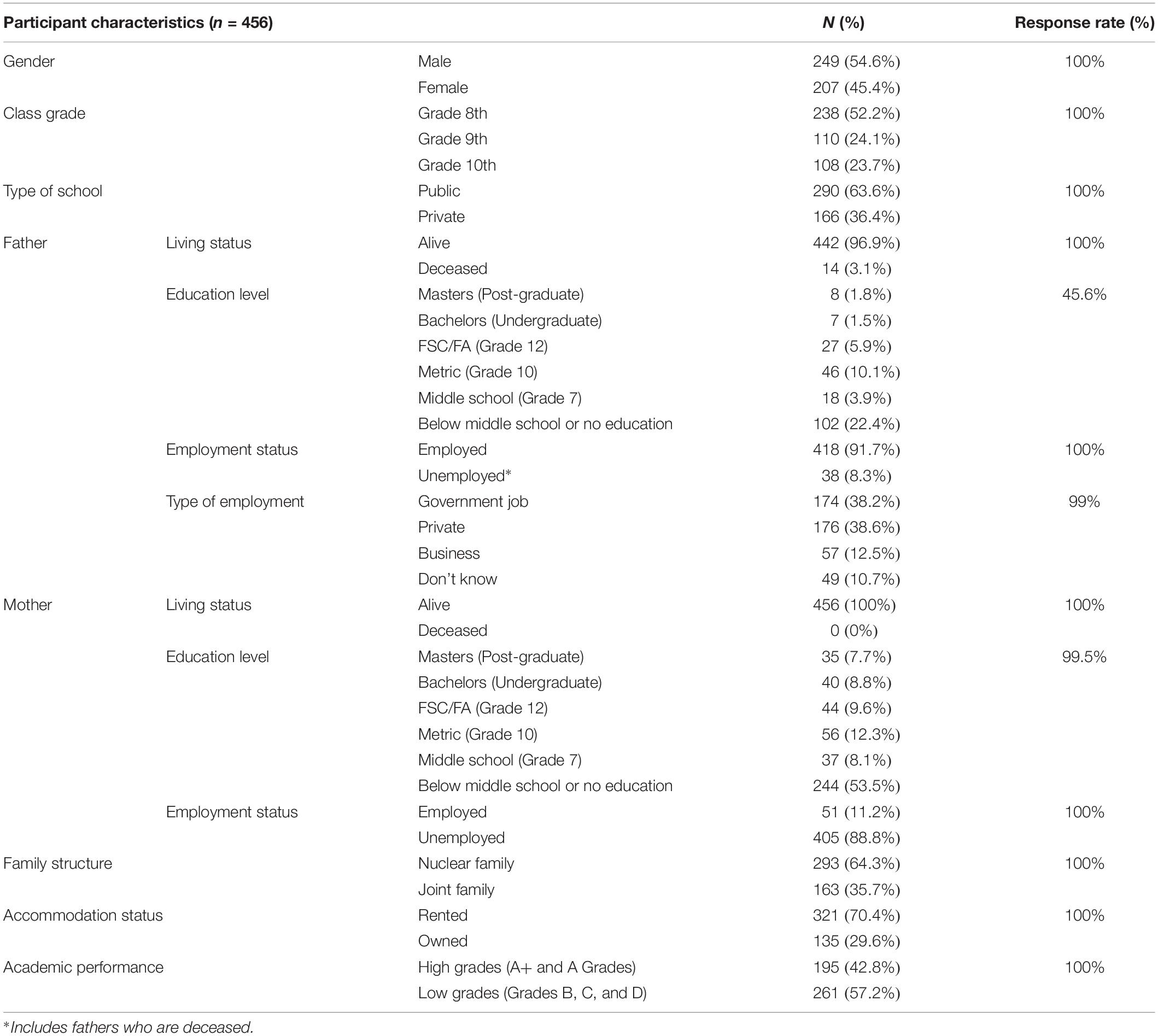

Participants and Descriptive Data

A total of 456 students were interviewed, with 249 (54.6%) males and 207 (45.4%) females. The majority (52.5%) were students of grade 8. Despite including an equal number of public and private schools, 63.6% of the students belonged to a public sector school. The reason may be due to the larger class strength in public schools in comparison to private schools. The nuclear family structure was dominant (64.3%), with most students living in rented accommodation (70.4%) with 42.8% reporting to have obtained high grades (A plus or A) in their latest internal examinations ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Participant and descriptive data.

Majority of the students had both parents alive at the time of the interview. While all students’ mothers were alive, 14 students reported their father to have passed away. Surprisingly, only 46% of the students were able to report their father’s level of education compared to 99.5% for their mother. 9.2% of students reported their father to have an education level of grade 12 or above compared to 26% regarding their mother’s qualification. This was in contrast to 90% of the fathers being employed compared to only 11% of the mothers ( Table 2 ).

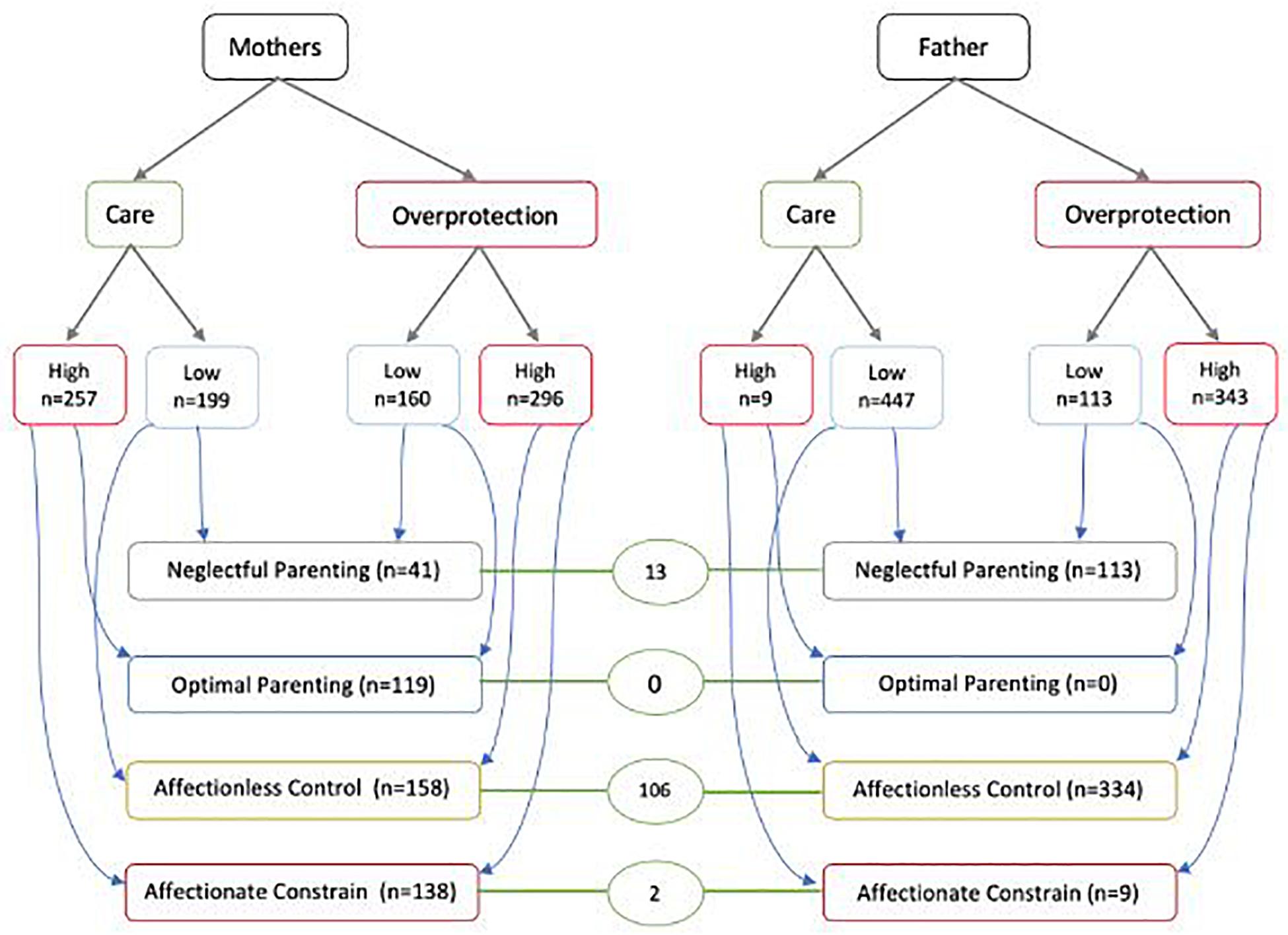

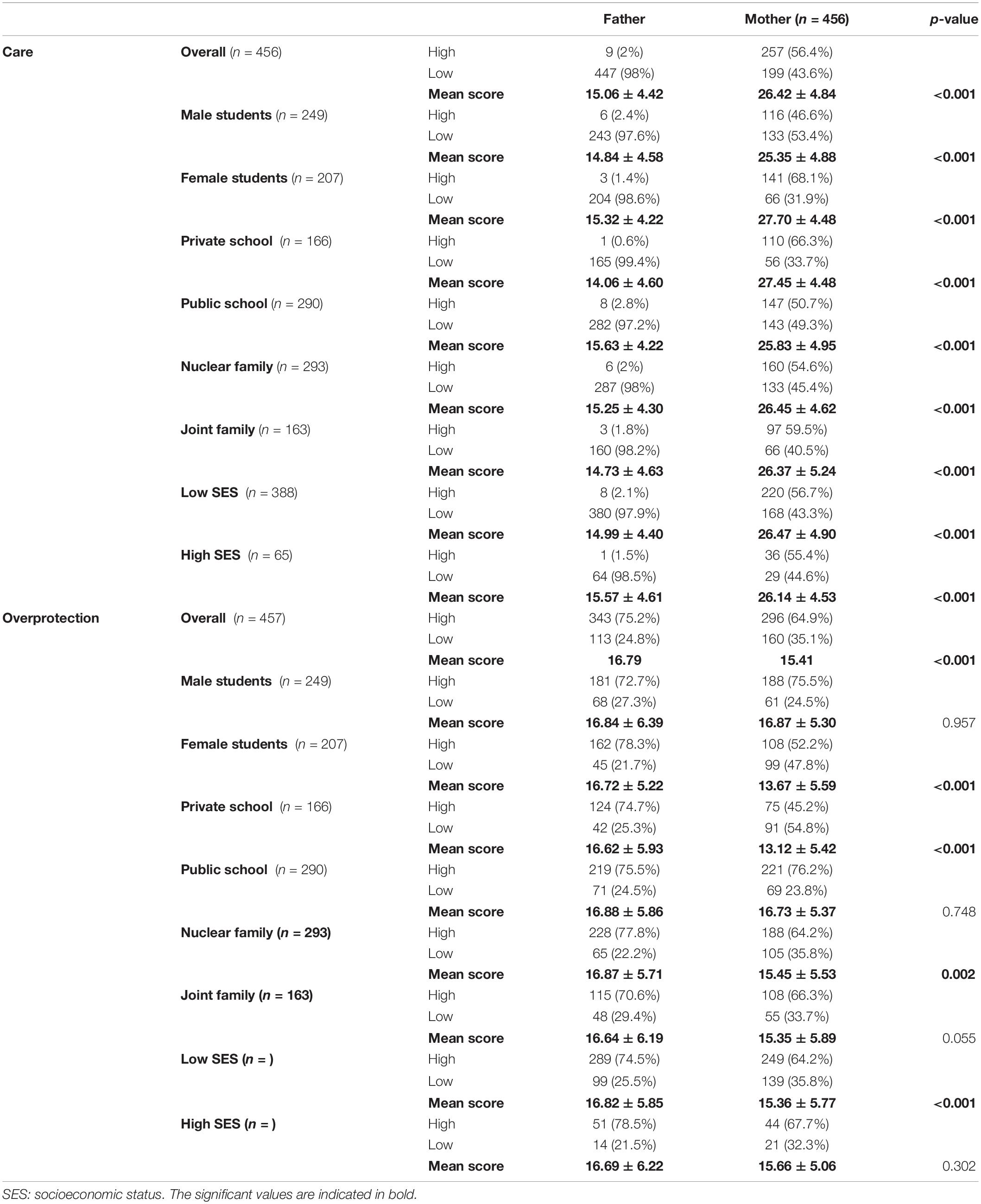

A Total of 257 (56%) students reported their mother to exhibit a high level of “care” vs. only 9 (2%) students reporting the same for their father. In terms of “overprotection,” 343 (75%) and 296 (65%) students reported a high level for their father and mother, respectively. Based on combinations of these measures, the most common parenting style for both fathers (73%) and mothers (35%) was affectionless control and the least common for fathers was optimal parenting (0%) and neglectful parenting for mothers (9%). 121 (26%) students had both parents with the same parenting style, with 23% students having both parents show affectionless control and not a single student with both parents showing optimal parenting ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. “Care,” “overprotection” and parenting styles for fathers and mothers as reported by students ( n = 456). Green circles represent students with both parents showing the same parenting style – none of the students received “Optimal parenting” from both parents while 106 students received affectionless control from both parents.

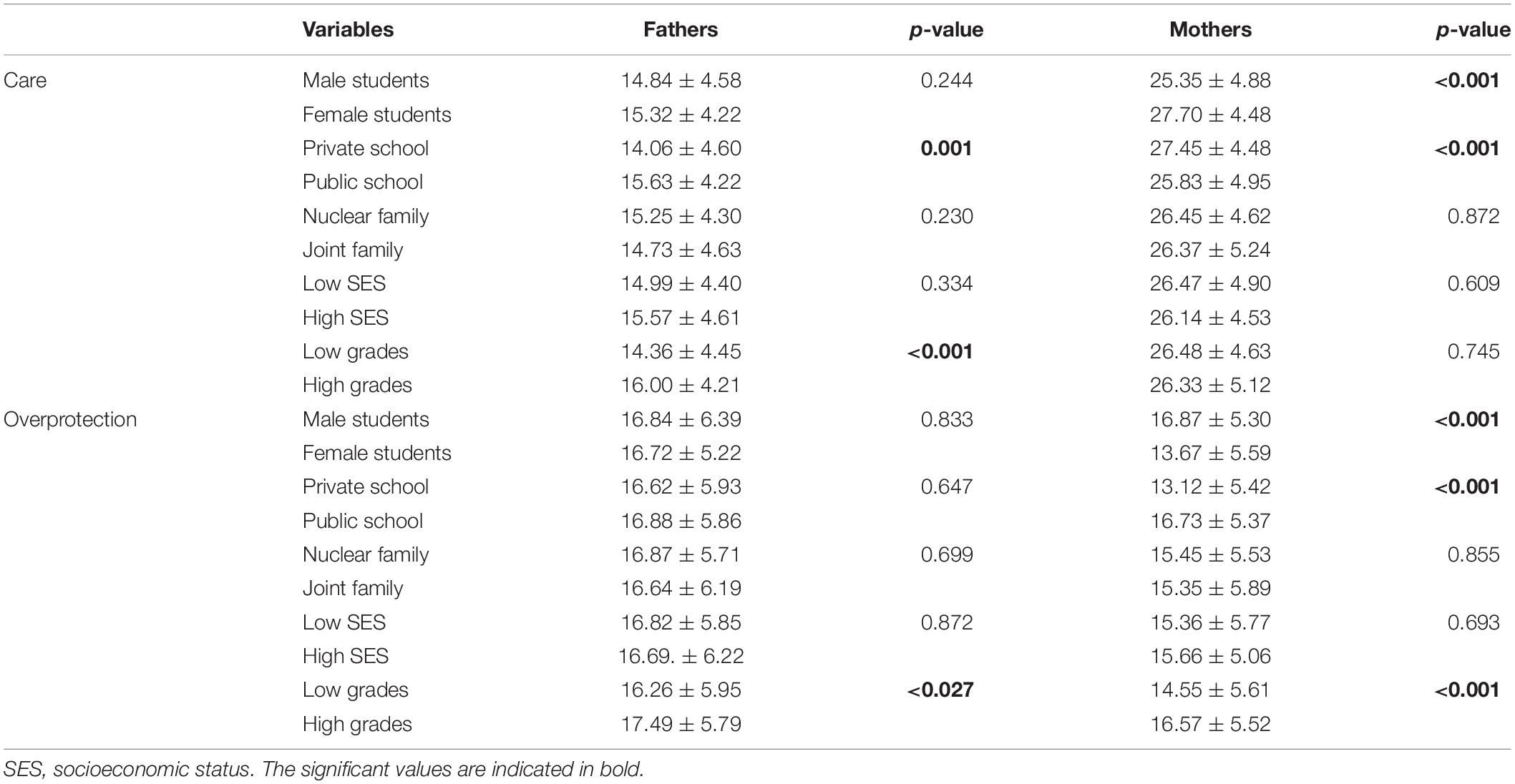

Determinants of High Grades

Our results show that high socioeconomic status [adjusted OR 2.78 (1.03, 7.52)], father’s education level till undergrad or above [adjusted OR 4.58 (1.49, 14.09)], father’s high “care” [adjusted OR 1.09 (1.01, 1.18)] and father’s affectionless control style of parenting [adjusted OR 3.23 (1.30, 8.03)] are significant factors contributing to high grades ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Academic performance: Determinants of “high” grades in the latest internal examinations.

Differences in “Care” and “Overprotection” Between Fathers and Mothers

The mean “care” score for mothers were significantly higher than fathers overall. The difference remained significant for male and female students, public and private schools, joint and nuclear family structures and low and high socioeconomic statuses ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Differences between mean “care” and “overprotection” scores between fathers and mothers.

Overprotection

The mean “overprotection” score was significantly higher for fathers overall. The difference remained significant for female students, private schools, nuclear family structure, and low socioeconomic status. However, there was no significant difference in mean “overprotection” scores between fathers and mothers for male students, public schools, joint family structures and high socioeconomic status ( Table 4 ).

Factors Associated With “Care” and “Overprotection” in Fathers and Mothers

The mean “care” score was significantly higher for fathers as reported by children in public schools and with higher grades. There was no significant difference in mean care scores based on student gender, socioeconomic status or family structure ( Table 5 ).

Table 5. Factors associated with “care” and “overprotection” for mothers and fathers.

For “overprotection” the only factor associated with a significantly higher mean score was “high” grades ( Table 5 ).

A significantly higher mean “care” score for mothers was reported by female students and students in public schools. No significant differences were observed for the other factors ( Table 5 ).

A significantly higher mean “overprotection” score was reported by male students, students in public schools and those with “high” grades for mothers ( Table 5 ).

Summary of Findings

Results of regression analysis show that socioeconomic status, father’s education level and fathers’ care scores have a significantly positive influence on the academic performance of adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. The most common parenting style for both fathers and mothers was affectionless control. However, affectionless control exhibited by the father was the only parenting style significantly contributing to improved academic performance.

Overall, the mean “care” score was higher for mothers and the mean “overprotection” score was higher for fathers. However, differences in “overprotection” were eliminated for male students, public schooling, joint family structures and high socioeconomic status.

Public schooling was associated with a significantly higher mean “care” score for both fathers and mothers and a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score for mothers. High grades were associated with a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score for both fathers and mothers and a significantly higher mean “care” score for fathers. For mothers, female students reported a significantly higher mean care score and male students reported a significantly higher mean “overprotection” score.

An additional interesting finding from the results of the study was that only about half the students were able to report their father’s level of education compared to almost a 100% for their mother. From amongst those who did report, less than 10% of the father’s had an education level equal or above grade 12 compared to a quarter of the mothers. However, only 11% of the mothers were employed in contrast to 90% of the fathers.

Previous Literature and Comparison of Main Findings

The results of our study have identified socioeconomic status, father’s education level and high care scores for fathers to be significant predictors of academic success in adolescent students. Previous literature has shown socioeconomic status to be a predictor of academic success ( Gamoran, 1996 ; Sander, 1999 ; Lubienski and Lubienski, 2006 ).

Parental education has been frequently associated with improved academic performance ( Dumka et al., 2008 ; Dubow et al., 2009 ; Masud et al., 2015 ). In 2011, a study by Farooq et al. described the factors affecting academic performance in 600 students at the secondary school level in a public school in Lahore, Pakistan. Results of their study also associate parental education level with academic success in students. However, their results are significant for the education level of the mother as well as the father. Additionally, they also reported significantly higher academic performance in females and in students belonging to a higher socioeconomic status, factors not significant in our study ( Farooq et al., 2011 ). Differences may be explained by cultural variations in Lahore and Peshawar within Pakistan, which should be explored further.

The description of parenting styles and behaviors has evolved over the years. With some variation in terminologies, the essence lies in a few common principles. Diana Baumrind initially described three main parenting styles based on variations in normal parenting behaviors: authoritative, authoritarian and permissive ( Baumrind, 1966 , 1967 ). Building on the concepts put forth by Baumrind, Maccoby and Martin identified two dimensions, “responsiveness” and “demandingness,” which could classify parenting styles into 4 types, three of those described by Baumrind with the addition of neglectful parenting ( Maccoby et al., 1983 ). The two dimensions, “responsiveness” and “demandingness,” often referred to as “warmth” and “control” in literature ( Lamborn et al., 1991 ; Tagliabue et al., 2014 ), are similar to the two measures, “care” and “overprotection” assessed by the parental bonding instrument ( Parker et al., 1979 ; Parker, 1989 ; Dudley and Wisbey, 2000 ). Based on this, the authoritative, authoritarian, permissive and neglectful parenting styles described by Baumrind and Maccoby are similar to the affectionate constraint, affectionless control, optimal, and neglectful styles as classified by the parental bonding instrument, respectively ( Baumrind, 1991 ; Cavedo and Parker, 1994 ).

Results of our study show that affectionless control, similar to the authoritarian style of parenting, adapted by the father is significantly associated with improved academic performance. This differs from the popularity of the authoritative parenting style, similar to affectionate constraint, in determining academic success in literature from western cultures ( Steinberg et al., 1989 , 1992 ; Deslandes et al., 1998 ; Aunola et al., 2000 ; Adeyemo, 2005 ; Masud et al., 2015 ; Pinquart, 2016 ; Checa et al., 2019 ). Evidence from societies with cultural similarities with Pakistan presents varied findings. A study from Iran shows support for the authoritarian parenting style similar to our study ( Rahimpour et al., 2015 ). A review of 39 studies published by Masud et al. (2015) in 2015 assesses the effect of parenting styles on academic performance ( Masud et al., 2015 #205). The review very aptly described how the authoritative parenting style is the dominant and most effective style in terms of determining academic performance in the West and European countries while Asian cultures show more promising results for academic success for the authoritarian style ( Dornbusch et al., 1987 ; Lin and Fu, 1990 ; Masud et al., 2015 ). The results of our study are in synchrony with these findings. However, our results also show that high father’s “care” scores are significant contributors to higher academic grades. Since no father showed optimal parenting and only 9 fathers had affectionate constraint, both parenting styles with high care scores, these results may be a reflection of the importance of father’s role in determining academic performance in Asian cultures. Findings supporting the authoritarian/affectionless control style may be due to the abundance of this parenting style. Perhaps a fairer comparison may be possible with a larger sample population with fathers showing all types of parenting styles equally.

Interpretation and Explanation of Other Findings

Observations of factors associated with and differences in “care” and “overprotection” between fathers and mothers may be attributed to reverse causality and should be used as hypothesis generating.

Our results show that mothers have higher mean “care” score and fathers have a higher mean “overprotection” score. Since these scores are based on perceptions of the child, part of these observations may be explained by the cultural norms of expression of love and concern by fathers and mothers. With the difference in “overprotection” being eliminated for male and female children, it is possible that mothers are more overprotective of their sons. Male gender preference in Pakistan may be an explanation for this ( Qadir et al., 2011 ).

Our results show lower employment rates for women despite higher education levels. The finding of higher education levels for females compared to males does not agree with national data, which reports findings from rural areas as well where education opportunities are limited for females ( Hussain, 2005 ; Chaudhry and Rahman, 2009 ). Our results provide a zoomed in look at an urban population, which may have progressed enough to improve women’s education but cultural norms, gender discrimination and lack of opportunity still prevent women from stepping into the workface ( Chaudhry, 2007 ; Begum and Sheikh, 2011 ).

Implications and Future Direction

The findings of our study may have implications for future research and policy making.

Affectionless control is associated with improved academic performance but further research investigating the effects of this style on other aspects of child development, particularly emotional and psychological health, is needed. Factors affecting care and overprotection need to be studied in more detail so that parenting workshops and interventions are tailored to our population. Results also suggest that fathers should play a stronger role in parenting of adolescent students. School policies should make it mandatory for both parents to attend parent-teacher meetings and assigned home activities should include both parents.

Limitations

Since the study is based on the urban population of Peshawar, results may not be generalizable to the adolescent students of the country which includes large rural populations. Academic performance was judged on latest internal examinations, the marking criteria for which may vary across schools. The use of external examinations would have standardized grades across schools but limited the sample to students of grade 9 and 10.

Our study concludes that socioeconomic status, father’s level of education and high care scores for fathers are associated with improved academic outcomes in adolescent students in Peshawar, Pakistan. Affectionless control is the most common parenting style as perceived by the students and when adapted by the father, contributes to better grades. Further research investigating the effects of demonstrating affectionless control on the emotional and psychological health of students needs to be conducted. Parenting workshops and school policies should include recommendations to increase involvement of fathers in the parenting of adolescent children.

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and stored as part of this study is available upon reasonable request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Khyber Medical University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

SM contributed in conceiving, designing, data acquisition, grant submission, and manuscript review. SHM involved in data analysis and manuscript writing. NQ involved in manuscript writing. MK was the principal investigator and supervisor for the project. FK and SK contributed in literature review and data management. All authors proofread and agreed on the final draft and accept responsibility for the work.

This project was graciously funded by the Research Promotion and Development World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (RPPH Grant 2016-2017, TSA reference: 2017/719467-0).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nazish Masud (King Saud bin Abdulaziz University), and Dr. Khabir Ahmad and Dr. Bilal Ahmad (The Aga Khan University) for their contributions to the project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02497/full#supplementary-material

Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 21, 407–412. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_12

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Adeyemo, D. A. (2005). Parental involvement, interest in schooling and school environment as predictors of academic self-efficacy among fresh secondary school students in Oyo State, Nigeria. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 3, 163–180.

Google Scholar

Aunola, K., Stattin, H., and Nurmi, J.-E. (2000). Parenting styles and adolescents’ achievement strategies. J. Adolesc. 23, 205–222. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0308

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Battle, J. (2002). Longitudinal analysis of academic achievement amonga nationwide sample of hispanic students in one-versus dual-parent households. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 24, 430–447. doi: 10.1177/0739986302238213

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Dev. 37, 887–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1966.tb05416.x

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genet. Psychol. Monogr. 75, 43–88.

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 11, 56–95. doi: 10.1177/0272431691111004

Bean, R. A., Barber, B. K., and Crane, D. R. (2006). Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: the relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. J. Fam. Issues 27, 1335–1355. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06289649

Beauvais, A. M., Stewart, J. G., DeNisco, S., and Beauvais, J. E. (2014). Factors related to academic success among nursing students: a descriptive correlational research study. Nurse Educ. Today 34, 918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.005

Begum, M. S., and Sheikh, Q. A. (2011). Employment situation of women in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 38, 98–113. doi: 10.1108/03068291111091981

Behzadi, B., and Parker, G. (2015). A Persian version of the parental bonding instrument: factor structure and psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 225, 580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.042

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev. 55, 83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836

Bluestone, C., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (1999). Correlates of parenting styles in predominantly working- and middle-class African American mothers. J. Marriage Fam. 61, 881–893. doi: 10.2307/354010

Cavedo, L., and Parker, G. (1994). Parental bonding instrument. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 29, 78–82.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Chaudhry, I. S. (2007). Gender inequality in education and economic growth: case study of Pakistan. Pakistan Horizon 60, 81–91.

Chaudhry, I. S., and Rahman, S. (2009). The impact of gender inequality in education on rural poverty in Pakistan: an empirical analysis. Eur. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci. 15, 174–188.

Checa, P., and Abundis-Gutierrez, A. (2017). Parenting and temperament influence on school success in 9–13 year olds. Front. Psychol. 8:543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00543

Checa, P., Abundis-Gutierrez, A., Pérez-Dueñas, C., and Fernández-Parra, A. (2019). Influence of maternal and paternal parenting style and behavior problems on academic outcomes in primary school. Front. Psychol. 10:378. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00378

Chow, H. P. (2000). The determinants of academic performance: Hong Kong immigrant students in Canadian schools. Can. Ethn. Stud. J. 32, 105–105.

Cohen, D. A., and Rice, J. (1997). Parenting styles, adolescent substance use, and academic achievement. J. Drug Educ. 27, 199–211. doi: 10.2190/QPQQ-6Q1GUF7D-5UTJ

Cutrona, C. E., Cole, V., Colangelo, N., Assouline, S. G., and Russell, D. W. (1994). Perceived parental social support and academic achievement: an attachment theory perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 66, 369–378. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.369

Dennis, J. M., Phinney, J. S., and Chuateco, L. I. (2005). The role of motivation, parental support, and peer support in the academic success of ethnic minority first-generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 46, 223–236. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0023

Desimone, L. (1999). Linking parent involvement with student achievement: do race and income matter? J. Educ. Res. 93, 11–30. doi: 10.1080/00220679909597625

Deslandes, R., Bouchard, P., and St-Amant, J.-C. (1998). Family variables as predictors of school achievement: sex differences in Quebec adolescents. Can. J. Educ. 23, 390–404.

Deslandes, R., Royer, E., Turcotte, D., and Bertrand, R. (1997). School achievement at the secondary level: influence of parenting style and parent involvement in schooling. McGill J. Educ. 32

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., and Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev. 58, 1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x

Dubow, E. F., Boxer, P., and Huesmann, L. R. (2009). Long-term effects of parents’ education on children’s educational and occupational success: mediation by family interactions, child aggression, and teenage aspirations. Merrill Palmer Q. 55, 224–249. doi: 10.1353/mpq.0.0030

Dudley, R. L., and Wisbey, R. L. (2000). The relationship of parenting styles to commitment to the church among young adults. Relig. Educ. 95, 38–50. doi: 10.1080/0034408000950105

Dumka, L. E., Gonzales, N. A., Bonds, D. D., and Millsap, R. E. (2008). Academic success of Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: the role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles 60, 588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z

Farooq, M. S., Chaudhry, A. H., Shafiq, M., and Berhanu, G. (2011). Factors affecting students’ quality of academic performance: a case of secondary school level. J. Qual. Technol. Manag. 7, 1–14.

Farsides, T., and Woodfield, R. (2003). Individual differences and undergraduate academic success: the roles of personality, intelligence, and application. Pers. Individ. Differ. 34, 1225–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00111-3

Flynn, D. M., and MacLeod, S. (2015). Determinants of Happiness in Undergraduate University Students. Coll. Stud. J. 49, 452–460.

Gamoran, A. (1996). Student achievement in public magnet, public comprehensive, and private city high schools. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 18, 1–18. doi: 10.3102/01623737018001001

Ginsburg, G. S., and Bronstein, P. (1993). Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Dev. 64, 1461–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02964.x

Hawkins, J. D. (1997). “Academic performance and school success: sources and consequences,” in Healthy Children 2010: Enhancing Children’s Wellness , eds R. P. Weissberg, T. P. Gullotta, R. L. Hampton, B. A. Ryan, and G. R. Adams, (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc), 278–305.

Hillstrom, K. A. (2009). Are Acculturation and Parenting Styles Related to Academic Achievement Among Latino students? dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Hussain, I. (2005). “Education, employment and economic development in Pakistan,” in Education Reform in Pakistan: Building for the Future , ed. R. M. Hathaway, (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars), 33–45.

Huver, R. M. E., Otten, R., de Vries, H., and Engels, R. C. (2010). Personality and parenting style in parents of adolescents. J. Adolesc. 33, 395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.012

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Urban Educ. 42, 82–110. doi: 10.1177/0042085906293818

Khalid, A., Qadir, F., Chan, S. W., and Schwannauer, M. (2018). Parental bonding and adolescents’ depressive and anxious symptoms in Pakistan. J. Affect. Disord. 228, 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.050

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J. L., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., and Hayek, J. C. (2006). What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative.

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., and Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 62, 1049–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x

Lin, C. Y. C., and Fu, V. R. (1990). A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Dev. 61, 429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02789.x

Linnenbrink, E. A., and Pintrich, P. R. (2002). Motivation as an enabler for academic success. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31, 313–327. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1471169

Liu, J., Li, L., and Fang, F. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Parental Bonding Instrument. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48, 582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.008

Lubienski, C., and Lubienski, S. (2006). Charter, Private, Public Schools and Academic Achievement: New Evidence from NAEP Mathematics Data. New York, NY: Columbia University.

Maccoby, E., Martin, J., Hetherington, E., and Mussen, P. (1983). “Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction,” in Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development , 4th Edn, Vol. 4, ed. E. M. Hetherington, (Hoboken. NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 101.

Masud, H., Thurasamy, R., and Ahmad, M. S. (2015). Parenting styles and academic achievement of young adolescents: a systematic literature review. Qual. Quant. 49, 2411–2433. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0120-x

McCabe, J. E. (2014). Maternal personality and psychopathology as determinants of parenting behavior: a quantitative integration of two parenting literatures. Psychol. Bull. 140, 722–750. doi: 10.1037/a0034835

McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., and Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: the role of learning-related social skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 15, 307–329. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(00)00069-7

Mujtaba, T., and Furnham, A. (2001). A cross-cultural study of parental conflict and eating disorders in a non-clinical sample. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 47, 24–35. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700103

Murphy, E., Wickramaratne, P., and Weissman, M. (2010). The stability of parental bonding reports: a 20-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 125, 307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.003

Osorio, A., and González-Cámara, M. (2016). Testing the alleged superiority of the indulgent parenting style among Spanish adolescents. Psicothema 28, 414–420.

Östberg, M., and Hagekull, B. (2000). A structural modeling approach to the understanding of parenting stress. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 29, 615–625. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_13

Parker, G. (1979). Reported parental characteristics in relation to trait depression and anxiety levels in a non-clinical group. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 13, 260–264. doi: 10.3109/00048677909159146

Parker, G. (1983). Parental Overprotection: A Risk Factor in Psychosocial Development. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton.

Parker, G. (1989). The parental bonding instrument: psychometric properties reviewed. Psychiatr. Dev. 7, 317–335.

Parker, G. (1990). The parental bonding instrument. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 25, 281–282.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., and Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 52, 1–10.

Parsasirat, Z., Montazeri, M., Yusooff, F., Subhi, N., and Nen, S. (2013). The most effective kinds of parents on children’s academic achievement. Asian Soc. Sci. 9, 229–242.

Pinquart, M. (2016). Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 475–493. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9338-y

Ponnet, K., Mortelmans, D., Wouters, E., Van Leeuwen, K., Bastaits, K., and Pasteels, I. (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Pers. Relat. 20, 259–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x

Qadir, F., Khan, M. M., Medhin, G., and Prince, M. (2011). Male gender preference, female gender disadvantage as risk factors for psychological morbidity in Pakistani women of childbearing age - a life course perspective. BMC Public Health 11:745. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-745

Qadir, F., Stewart, R., Khan, M., and Prince, M. (2005). The validity of the Parental Bonding Instrument as a measure of maternal bonding among young Pakistani women. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 40, 276–282. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0887-0

Rahimpour, P., Direkvand-Moghadam, A., Direkvand-Moghadam, A., and Hashemian, A. (2015). Relationship between the parenting styles and students’ educational performance among Iranian girl high school students, a cross- sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9:JC05–JC07. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15981.6914

Sander, W. (1999). Private schools and public school achievement. J. Hum. Resour. 34, 697–709. doi: 10.2307/146413

Sanders, M. G. (1998). The effects of school, family, and community support on the academic achievement of African American adolescents. Urban Educ. 33, 385–409. doi: 10.1177/0042085998033003005

Shute, V. J., Hansen, E. G., Underwood, J. S., and Razzouk, R. (2011). A review of the relationship between parental involvement and secondary school students’ academic achievement. Educ. Res. Int. 2011:915326.

Simons, R. L., Beaman, J., Conger, R. D., and Chao, W. (1993). Childhood experience, conceptions of parenting, and attitudes of spouse as determinants of parental behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 55, 91–106. doi: 10.2307/352961

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., and Melby, J. N. (1990). Husband and wife differences in determinants of parenting: a social learning and exchange model of parental behavior. J. Marriage Fam. 52, 375–392. doi: 10.2307/353033

Smith, C. L. (2010). Multiple determinants of parenting: predicting individual differences in maternal parenting behavior with toddlers. Parenting 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/15295190903014588

Steinberg, L., Elmen, J. D., and Mounts, N. S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Dev. 60, 1424–1436. doi: 10.2307/1130932

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., and Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. 63, 1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x

Tagliabue, S., Olivari, M. G., Bacchini, D., Affuso, G., and Confalonieri, E. (2014). Measuring adolescents’ perceptions of parenting style during childhood: psychometric properties of the parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. Psicol. Teoria e Pesquisa 30, 251–258. doi: 10.1590/s0102-37722014000300002

Tomul, E., and Savasci, H. S. (2012). Socioeconomic determinants of academic achievement. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 24, 175–187. doi: 10.1007/s11092-012-9149-9143

Vacha, E. F., and McLaughlin, T. F. (1992). The social structural, family, school, and personal characteristics of at-risk students: policy recommendations for school personnel. J. Educ. 174, 9–25. doi: 10.1177/002205749217400303

Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., and Castro, K. S. (2007). Children’s effortful control and academic competence: mediation through school liking. Merrill Palmer Q. 53, 1–25. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2007.0006

Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., et al. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 12, 1500–1524.

Wang, Q., and Leichtman, M. D. (2000). Same beginnings, different stories: a comparison of American and Chinese children’s narratives. Child Dev. 71, 1329–1346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00231

Weis, M., Trommsdorff, G., and Muñoz, L. (2016). Children’s self-regulation and school achievement in cultural contexts: the role of maternal restrictive control. Front. Psychol. 7:722. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00722

Weiss, L. H., and Schwarz, J. C. (1996). The relationship between parenting types and older adolescents’ personality, academic achievement, adjustment, and substance use. Child Dev. 67, 2101–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01846.x

Wilhelm, K., Niven, H., Parker, G., and Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. (2005). The stability of the parental bonding instrument over a 20-year period. Psychol. Med. 35, 387–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003538

York, T., Gibson, C., and Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and measuring academic success. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 20, 1–20.

Zahedani, Z. Z., Rezaee, R., Yazdani, Z., Bagheri, S., and Nabeiei, P. (2016). The influence of parenting style on academic achievement and career path. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 4, 130–134.

Zakeri, H., and Karimpour, M. (2011). Parenting styles and self-esteem. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 758–761. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.302

Zhang, X., Hu, B. Y., Ren, L., Huo, S., and Wang, M. (2019). Young Chinese children’s academic skill development: identifying child-, family-, and school-level factors. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2019, 9–37. doi: 10.1002/cad.20271

Keywords : parenting styles, academic performance, adolescent students, Pakistan, care, overprotection, parental bonding instrument

Citation: Masud S, Mufarrih SH, Qureshi NQ, Khan F, Khan S and Khan MN (2019) Academic Performance in Adolescent Students: The Role of Parenting Styles and Socio-Demographic Factors – A Cross Sectional Study From Peshawar, Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 10:2497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02497

Received: 16 May 2019; Accepted: 22 October 2019; Published: 08 November 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Masud, Mufarrih, Qureshi, Khan, Khan and Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarwat Masud, [email protected] ; Muhammad Naseem Khan, [email protected] ; [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Academic performance of children in relation to gender, parenting styles, and socioeconomic status: What attributes are important

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Sociology, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Rural Sociology, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Sociology & Psychology, University of Swabi, Swabi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Data curation

Affiliation Head of Department of Pakistan Studies, Islamia College, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Affiliation Department of Social Work, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Conceptualization

Affiliation Department of Sociology, The Women University, Multan, Punjab, Pakistan

Roles Methodology

Affiliation University of Malakand Women Campus, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Affiliation Department of Tourism & Hotel Management, University of Swabi, Swabi, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Business Administration, ILMA University, Karachi, Pakistan

Affiliation Department of Law, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Roles Project administration

Roles Investigation

- Nayab Ali,

- Asad Ullah,

- Abdul Majid Khan,

- Yunas Khan,

- Sajid Ali,

- Aisha Khan,

- Bakhtawar,

- Asad Khan,

- Maaz Ud Din,

- Published: November 15, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286823

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

What are the effects of parenting styles on academic performance and how unequal are these effects on secondary school students from different gender and socioeconomic status families constitute the theme of this paper. A cross-sectional and purposive sampling technique was adopted to gather information from a sample of 448 students on a Likert scale. Chi-square, Kendall’s Tau-c tests and hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to determine the extent of the relationship among the variables. Chi-square and Kendall’s Tau-c (T c ) test results established that the socioeconomic status of the respondent’s family explained variation in children’s academic performance due to parenting style; however, no significant difference was observed in the academic performance of students based on gender. Furthermore, hierarchal multiple regression analysis established that the family’s socioeconomic status, authoritative parenting, permissive parenting, the interaction of socioeconomic status and authoritative parenting, and the interaction of socioeconomic status and permissive parenting were significant predictors (P<0.05) of students’ academic performance. These predictor variables explained 59.3 percent variation in the academic performance of children (R2 = 0.593). Results of hierarchal multiple regression analysis in this study ranked ordered the most significant predictors of the academic performance of children in the following order. Family socioeconomic status alone was the strongest predictor (β = 18.25), interaction of socioeconomic status and authoritative parenting was the second important predictor (β = 14.18), authoritative parenting alone was third in importance (β = 13.38), the interaction of socioeconomic status and permissive parenting stood at fourth place in importance (β = 11.46), and permissive parenting was fifth (β = 9.2) in influencing academic performance of children in the study area. Children who experienced authoritative parenting and were from higher socioeconomic status families perform better as compared to children who experienced authoritarian and permissive parenting and were from low socioeconomic status families.

Citation: Ali N, Ullah A, Khan AM, Khan Y, Ali S, Khan A, et al. (2023) Academic performance of children in relation to gender, parenting styles, and socioeconomic status: What attributes are important. PLoS ONE 18(11): e0286823. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286823

Editor: Ikram Shah, COMSATS University Islamabad, PAKISTAN

Received: September 9, 2022; Accepted: May 24, 2023; Published: November 15, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Ali et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Academic performance is the process of acquiring knowledge and skills that provide the foundation for development [ 1 ]. Academic performance refers to the “achievement of educational benchmarks”, therefore, most of the educational efforts of students, teachers, parents and educational institutions revolve around achieving these educational goals to provide a sound foundation for national development and meet the challenges of the modern world [ 2 – 4 ]. Measurement of academic performance via standardized tests and examinations and its verification in a system of grade marks or percentage points is a universally accepted norm [ 5 , 6 ]. Good academic performance has been related to successful development trajectories and better life performance for the persons possessing it as well as for national development. On the contrary, poor academic behavior is linked to academic failure, maladjustment, poor access to services and opportunities or alternatively access to low-paying and less rewarding jobs and low productivity in later life. Also, when a state has a larger population of people with inferior academic credentials, it is less able to implement productivity-boosting technology and innovative working methods, which ultimately causes the nation to fall in the international rankings for its socioeconomic standing [ 7 ]. The reasons for the poor academic achievements of students in poor and developing countries are almost similar. Several factors are associated with the academic performance of students. These factors include individual, social, economic and institutional. Some of the most important predictors of child academic achievements include school attendance, student’s interest in the study, hard work, dedication, self-confidence, family support, parenting style, family socioeconomic status, school environment and neighborhood facilities [ 8 – 10 ], peer influence and parent involvement in children education [ 11 , 12 ]. Similarly, Radhika found that classroom size, teaching methodology, teachers’ capabilities, facilities and learning environment at school affect the academic performance of students [ 13 ].

This study is designed in light of Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model. Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological framework provides a theoretical foundation to connect multi-layered patterns of interaction of personal relationships and social settings in institutions that shape students’ behaviour, learning motivation and academic performance. Thus, the academic performance of children from the study area is supposedly having links with some micro-, meso-, exo- and macro-level systems that are explained under Bronfenbrenner socio-ecological model. However, due to time and financial constraints, as well as the direct influence of the two levels (Micro and Meso levels) of Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model, the current study focused only on these two levels. This research study has three main objectives: (1) to examine the association between parenting style and academic performance of children, (2) to know about the variation in academic performance of children with respect to parenting style on the basis of student gender and family socioeconomic status, and (3) to measure the relationship between parenting style and family socioeconomic status on the academic performance in isolation and interaction with each other.

National and international scenario

According to the Global Human Capital ranking of 130 countries, the less-developed and developing countries like African and South Asian countries lack behind the developed countries and make up the lower end of the regional rankings due to poor investment in education, low-skilled workforce, poor utilization of skills and little know-how of utilization of skills. Moreover, out of 214 million children in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Central and Southern Asia states do not achieve minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics and 81% of these children have ages of 6 to 14 years [ 14 ]. According to the Global Human Capital ranking of 130 countries, Pakistan stands at 125 th , which is well below the neighboring countries in South Asia such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh and India which ranks 70, 98, 111 and 103 respectively [ 15 ]. Pakistan, the 5 th most populous country in the world, has a population of more than 200 million. More than two third of its population live in rural areas. Between urban and rural populations, there are substantial disparities. For instance, the literacy rate is 53% in rural areas whereas 76% in urban ones. Urban areas (18% rural compared to 74% urban) have approximately four times the likelihood of having access to vital developmental services [ 16 ]. According to UNICEF in addition to the 40 million that are enrolled in school, there are presently 22.8 million more Pakistani children not in school. Following Nigeria, this country has the second-highest proportion of out-of-school children worldwide. 5.3 million of the 22.8 million children in this group are dropouts, and 17.5 million have never attended school [ 17 ]. The average percentage of students who passed all subjects in the science and arts groups in 2019 was 68.24% and 36.83% respectively. In 2018, the scientific group had a cumulative average pass percentage of 54.99%, while the arts group had a pass percentage of 38.99%. In 2017, the science group had a cumulative average pass percentage of 60.05%, while the arts group had a pass percentage of 42.29%. In 2016, the science group’s cumulative average pass rate was 54.11%, while the arts group was 44.95%. In 2015, the science group’s cumulative average pass rate was 46.92%, while the arts group was 34.22%. In the same way, a high number of students took the exams in 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015, but fewer students passed with low marks, which was an alarming situation in secondary education in Pakistan [ 18 , 19 ]. On a regional basis in the country, District Malakand is on top as per the last report of Alif Ailaan and SDPI on education scores. However, the last result of passing students in the Secondary Schools Certificate (SSC) examination is 69.73 percent and 30.27 percent of students remained unsuccessful [ 20 ].

Theoretical background

From long ago educationists and researchers are interested in exploring various determinants of students’ academic performance ranging from child personal factors to contextual factors. Some of the most echoed theories are achievement goal theory, self-determination theory, social learning theory, and socio-ecological model. The achievement goal theory explains that students’ academic achievements are associated with students’ personal factors i.e. their personal goal orientations and self-determination. The theory bifurcates the personal goal into two main categories namely mastery goal (goals for personal improvement and gaining knowledge for one’s own sake) and performance goals (to perform to supersede others in terms of academic output). These two types of goals help children in their development and learning (understanding and performing hard tasks) and keep them from failing through performance (to outperform and beat others) respectively [ 21 – 24 ]. Empirical research based on achievement goal theory made it evident that mastery goal improved students’ interest in learning, and enhanced their self-efficacy, self-determination and cognitive skills, whereas performance goal focused on the exercise of abilities for success [ 25 – 27 ]. A combination of mastery and performance goals contributes towards overall academic achievements [ 28 ]. The achievement goal theory was criticized for its broader applicability as its main focuses are on interpersonal predictors of achievements at individuals’ personal or at a very micro level [ 29 ]. Other researchers found some conflicting outcomes that were associated with performance goal orientations. Furthermore, some of the students, despite their maladaptive behavior towards performance and goal orientations, secured better grades which are inconsistent with the achievement goal literature [ 30 ]. Moreover, this theory could not take into consideration multiple dimensions at broader levels to explain the academic performance of children holistically [ 31 ].

Self-determination theory (SDT) is another theory to explain students’ classroom performance and is based on the premise of motivation. The theory assumes that all students possess innate tendencies for growth (intrinsic motivation) which is the motivational foundation for better classroom engagement and appropriate school functioning [ 32 – 37 ]. The theory further explains that motivation from teachers and enabling facilities at school (extrinsic motivation) provide a further boost to the inner motivational resources of students in facilitating their high-quality engagement, therefore, the academic achievements of students are reliant on intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [ 38 ]. This motivational phenomenon presented and explained self-determination theory along with its associated five other theories i.e. basic needs theory, organismic integration theory, goal contents theory, cognitive evaluation theory and causality orientations theory.

The basic needs theory focuses on psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) and magnifies the importance of intrinsic motivation, positive engagement, effective functioning and psychological well-being [ 39 ]. Organismic integration theory explains extrinsic motivation and its relationship with students’ academic socialization [ 40 , 41 ]. Goal contents theory compares intrinsic goals and extrinsic goals to elucidate how intrinsic goals support psychological well-being, whereas, extrinsic goals poster psychological ill-being [ 42 , 43 ]. Cognitive evaluation theory is another micro theory that emerged from SDT that was developed to predict the positive and negative effects of extrinsic goals on intrinsic motivation Causality orientation theory is the fifth offshoot of SDT that identifies individual differences among students in terms of their motivation and engagement. It also reflects on the fact that some students prefer autonomy, whereas others perform better in a controlled environment [ 44 ].

The SDT theory, however, is criticized on its conceptual grounds as empirical studies have revealed some adverse effects of rewards on motivation. Moreover, the application of this theory to real life is considered doubtful due to complex social events. Furthermore, the motivation that is generated by rewards, in the context of complex tasks that make up most of the human lives in their profession, is short-term and shallow. Excessive focus on rewards is also found detrimental to creativity and true engagement. The critique of SDT, therefore, rightly says that the creation of an atmosphere in which people feel free to act independently and creatively towards shared goals is much harder. Other social psychologists say that self-determination theory (SDT) is still under development and searching for new avenues in social psychology to explore [ 45 ].

Social learning theory is based on Banduras’ Bobo Doll experiments during the 1960s. This theory tries to establish that social learning is the outcome of observing and interacting with others. The theory was later on named “social cognitive theory” according to which learning occurs when there is reciprocal interaction of person between environments which results in a specific behavior. The interaction of a person with the environment stimulates behavior which in turn affects the person and the environment. Therefore, the learning process is a complex interplay of these factors which is termed by Banduras’ as reciprocal determinism [ 46 , 47 ]. Therefore, it is not only the students’ belief in their abilities that shape their academic achievements, rather, the social environment at family, school, neighborhood, peers and mass media are also important in shaping the learning outcomes of children [ 48 ].

The social learning theory is criticized for disregarding the emotional or motivational basis of learning behavior. Moreover, the operationalization of this theory in its entirety is also questioned. Some of the assumptions of the theory are disproved through empirical research for example the assumption that “the environment will bring changes in the person automatically”, does not always stand true. In addition, the extent to which the factors of person, environment and behavior influence the actual learning behavior is not clear. The theory has also overlooked the biological determinism and maturation effect on the learning process [ 49 ].

After discussing the major theme and criticisms on the above theories, there emerges a desire to focus on such a model that can help understand the multiple layers of youth ecology that promote academic growth and limit negative educational outcomes in the children.

One of the most widely used models in this regard is Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model which explains various factors of child development at different levels [ 50 – 53 ]. This model visualizes the environment of each individual residing in society into individually observable distinct patterns of layers. The multi-layered pattern of interaction of personal relationships, social settings and institutions shapes students’ behaviour, learning motivation and academic performance [ 54 – 56 ]. This theory divides these patterns of interaction into a system of four levels i.e. micro-level systems, meso-level systems, exo-level systems and macro-level systems. The micro-level system is the closest environment in which a student lives and interacts; it includes home, neighbourhood, and school. The meso-level system includes the interaction of two micro-level systems such as the interaction between parents and teachers and between parents and neighbours. The micro- and meso-level systems have a direct influence on child learning and performance. The other two levels, exo-level (parents, workplace and their association) and macro-level (culture, policies) system have no direct effect on the children and the children are not directly involved in that [ 57 – 59 ].

Empirical studies have also identified multiple determinants of children’s academic performance that are systematically framed in Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model [ 60 – 62 ]. However, parenting style (a micro-level factor refers to specific behaviours and strategies used by parents to control, socialize and establish an emotional relationship with their children) and family socioeconomic standing seems to be the most emphasized factors [ 63 – 66 ]. Numerous studies show overwhelming evidence of the important role played by parenting style in influencing the academic performance of children [ 67 , 68 ]. Based on various dimensions and characteristics of parenting, Baumrind identified three types of parenting styles that had profound effects on behaviour of children. The typology of parenting style included authoritative, authoritarian and permissive parenting. This typology of parenting style is based on responsiveness (warmth, clarity of communication, acceptance and involvement) and demandingness (control, supervision and maturity demands) as valued by parents [ 69 ]. Authoritative parenting is linked with a high level of both responsiveness and positive demandingness, the authoritarian parenting style is characterized by low responsiveness and high demandingness, and the permissive parenting style is based on high responsiveness and low demandingness [ 70 ]. Specific parental behaviour that influences the academic performance of children via authoritative parenting includes warmth and a democratic environment in the family, under which children openly participate in decision-making, discuss their concerns and have a positive relationship with their parents. From the parental side, authoritative parents enforce rules and norms, provide guidance and impose sanctions when necessary. Authoritarian parents are strict to the extent of harshness that limits child’s participation in family discussions and sharing problems with parents. On the other extreme, permissive parents provide limitless freedom to the children and ignore their deviance with no or very low guidance to discipline the children [ 71 ].

Parenting style is an important predictor of the academic performance of children to the extent that in some cases it may even offset the negative effects of socioeconomic status and poor neighbourhood in achieving better academic grades. However, Sirin reported based on a meta-analysis of 58 studies that parental socioeconomic status (education, occupation and income) is the strongest predictor of academic achievements and that low socioeconomic status leads to lower academic achievements of students [ 72 , 73 ]. For some researchers, a secured socioeconomic status is at par with other micro-level variables such as parenting style, home, school and neighbourhood. in shaping the academic achievements of the children, and for others, the effect of socioeconomic status was merely like a catalyst that boosted the academic performance of children when combined with appropriate parenting, positive peers, secure living and conducive school environment. The home locality, access to health and access to educational and recreational services are the functions of high socioeconomic status. Whereas, low enrolment and low academic performance are common in families with low socioeconomic status [ 74 , 75 ]. Gender is another dividing line that distinguishes the academic performance of male and female children. In egalitarian societies, the gender-based distinction is not as wider as compared to that in a patriarchal society where males are preferred over females [ 76 , 77 ]. Furthermore, some aspects of academic learning like engagement with school, self-esteem and enthusiasm for studies were excelled more by girls than boys, however, the socioeconomic system in patriarchal families was more favourable to boys than girls to support them in achieving higher academic grades [ 78 ].

Literature review

Biological determinists lay huge emphasis on hereditary and biological factors in understanding behaviour-related problems in children. At the same time, certain social factors may also prove deterministic in putting youth in a disadvantaged position in an unequal society, as the benefits of some interventions may yield different consequences for youth from different socioeconomic groups. Therefore, the stories of psychological stresses, mental illnesses, academic failures and unsuccessful life are more pronounced in the poor segment of society [ 79 ]. A review of international and national literature discloses a gradual decrease in school dropout rates during past decades. However, a major chunk of educated folk did not acquire appropriate academic grades. As a result, most of them remain unemployed because they barely manage to enter the labour force [ 80 , 81 ].

The global picture of human capital ranking shows that the poor and developing countries of South Asia and Africa including Pakistan are placed near the bottom of this ranking due to poor investment in education, low-skilled workforce, poor utilization of skills and little know-how of utilization of skills. The government in Central and Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa invested heavily in the education sector to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education for all children by 2015. This investment resulted in an increase in the net enrolment rate. However, these countries are still faced with the challenges of retention rate and quality education [ 82 ]. World Bank carried out a survey and reported that worldwide 617 million children and adolescents are not been able to achieve minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. Among these children, next to Sub-Saharan Africa are the Central and Southern Asia states where 81% of children and adolescents are not achieving proficiency outcomes [ 83 ]. The literacy percentage in Pakistan, at 57%, is significantly lower than that of its neighbouring countries. Given that primary school is where formative learning occurs, the dropout rate of 22.7 Percent (third highest in the region after Bangladesh and Nepal) is a grave issue. According to the 2016 Global Education Monitoring Report of the United Nations, Pakistan is 60 years behind in secondary education and 50 years behind in basic education in terms of meeting international educational standards. The children not attending school at the elementary, secondary, and upper secondary are 5.6, 5.5, and 10.4 million in numbers respectively. This results in an alarming and mind-boggling situation for the whole nation [ 84 , 85 ].