By the People: Essays on Democracy

Harvard Kennedy School faculty explore aspects of democracy in their own words—from increasing civic participation and decreasing extreme partisanship to strengthening democratic institutions and making them more fair.

Winter 2020

By Archon Fung , Nancy Gibbs , Tarek Masoud , Julia Minson , Cornell William Brooks , Jane Mansbridge , Arthur Brooks , Pippa Norris , Benjamin Schneer

The basic terms of democratic governance are shifting before our eyes, and we don’t know what the future holds. Some fear the rise of hateful populism and the collapse of democratic norms and practices. Others see opportunities for marginalized people and groups to exercise greater voice and influence. At the Kennedy School, we are striving to produce ideas and insights to meet these great uncertainties and to help make democratic governance successful in the future. In the pages that follow, you can read about the varied ways our faculty members think about facets of democracy and democratic institutions and making democracy better in practice.

Explore essays on democracy

Archon fung: we voted, nancy gibbs: truth and trust, tarek masoud: a fragile state, julia minson: just listen, cornell william brooks: democracy behind bars, jane mansbridge: a teachable skill, arthur brooks: healthy competition, pippa norris: kicking the sandcastle, benjamin schneer: drawing a line.

Get smart & reliable public policy insights right in your inbox.

- About Democracy Web

- How To Use Democracy Web

- About Freedom in the World

- About the Authors

- Questionnaire 1

- Introduction: What Is Democracy?

- Essential Principles

- South Africa

- Study Questions

- Essential Principles and History

- Netherlands

- Philippines

- Saudi Arabia

- North Korea

- General Resources

- Map of freedom

- Albert Shanker Institute

Introduction: What Is Democracy? by Danielle Allen

| Danielle Allen Democracy is a word that is over 2500 years old. It comes from ancient Greece and means “the power of the people.” When democracy was first invented, in ancient Athens, the most stunning feature of this new form of government was that poor men were allowed to participate alongside rich men in determining the fate of the city: whether to go to war; how to distribute the proceeds from public silver mines; whether to put those convicted of treason to death. In ancient Athens, all male citizens could gather together in the assembly to vote on issues of this kind. In ancient Rome, by contrast, the republic of Rome established a “mixed” regime in which some offices were held by the wealthy and some by representatives of the poor. Rather than throwing everyone together in a single decision-making group, the Romans tried to balance the interests of the rich and of the poor by giving them different roles in the political system. Nonetheless, both Athens and Rome understood themselves to have built political systems that rested on the voice of the people and that secured the freedom of a body of free and equal citizens strong enough to protect themselves from outside sources of domination and also committed enough to the rule of law to protect all citizens from domination by one another. The light went out for ancient democratic and republican forms of government respectively when Alexander the Great conquered Athens and when Julius Caesar overthrew the free Roman Republic and transformed it into an empire, headed by an emperor. Democracy would be revived, however, in Italian city-states in the early modern period and then in its modern form with the American Revolution in 1776. The modern revival of democracy has brought us twelve key concepts that the ancients didn’t have, or that vary significantly from their ancient variants. These are: (1) Consent of the Governed; (2) Free Elections; (3) Constitutional Limits; (4) Majority Rule, Minority Rights; (5) Transparency and Accountability; (6) Multiparty System; (7) Economic Freedom; (8) Rule of Law; (9) Human Rights; (10) Freedom of Expression; (11) Freedom of Association; and (12) Freedom of Religion. Taken together, these twelve concepts are the building blocks of modern, representative democracies. Our democracies are too big for all citizens to gather together to decide questions of state and the public good. Instead, we have representation. We elect people, our representatives, to make those decisions for us. With every election, we hold our representatives to account. Have they taken the country in a general direction to which we consent? We ensure that our governments rest on the consent of the governed by routinely holding free and fair elections. To make these elections meaningful, we need transparency about what our representatives have done. Only if we know what they have done, can we hold them to account for their actions. Why do we care that governments should rest on the consent of each and every one of us? Being human involves seeking to control one’s life. Achieving that requires having a role in politics because political decisions have such a big impact on our life. The idea of human rights captures the notion that every human being ought to have a chance to control his or her own life, including through political participation. Of course, being able to control one’s own life requires a lot more than just participating in politics. It also requires being able to spend time with those whom one chooses. It requires being able to express one’s views and to develop one’s beliefs as one chooses. This explains the importance of freedom of association, freedom of expression, and freedom of religion. Of course, it’s also important to point out that those freedoms—to speak one’s mind, to gather together with those whom one chooses, and to control one’s own beliefs—are necessary if one is going to participate politically. These freedoms give us the chance to control our private lives but they are also the necessary tools of political participation. Economic freedom-the freedom to control one’s own property—is equally necessary if one is going to control one’s own life and one’s public role. Now, making it possible for people to control their own lives, both privately and in public through politics, is not merely a matter of listing some important rights that we hold up as ideals. We also have to build institutions that work to protect those rights. Modern democracy differs the most from the ancient variants in the kinds of institutions it has invented to secure these rights. Some of the key inventions include written constitutions that identify the powers of government and how they should be wielded as well as the limits on those powers; a recognition that constitutions need to protect minorities from the power held by majority voting blocs; and formal political parties with platforms that help citizens organize their disputes and contests with one another. These basic building blocks—an overarching goal of consent of the governed; a set of rights that give people the chance to control their own fates; and institutions whose purpose is to balance power so that it does remain, ultimately, in the hands of the people—show up again and again in democracies all over the world. But every democracy describes the overarching goal slightly differently; it establishes its own priorities among the rights, especially when they come into conflict; and it arranges its institutions to suit its own people. Nonetheless, by looking at many comparative cases of democracy, one can come to see how beneath the surface differences, they share a basic DNA, a combination of ideals and institutions that work to put power in the hands of ordinary people. is Director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics at Harvard University and professor in Harvard’s Department of Government and Graduate School of Education. She is a political theorist who has published broadly in democratic theory, political sociology, and the history of political thought.

|

Introductory essay

Written by the educators who created Cyber-Influence and Power, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in their field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

Each and every one of us has a vital part to play in building the kind of world in which government and technology serve the world’s people and not the other way around. Rebecca MacKinnon

Over the past 20 years, information and communication technologies (ICTs) have transformed the globe, facilitating the international economic, political, and cultural connections and exchanges that are at the heart of contemporary globalization processes. The term ICT is broad in scope, encompassing both the technological infrastructure and products that facilitate the collection, storage, manipulation, and distribution of information in a variety of formats.

While there are many definitions of globalization, most would agree that the term refers to a variety of complex social processes that facilitate worldwide economic, cultural, and political connections and exchanges. The kinds of global connections ICTs give rise to mark a dramatic departure from the face-to-face, time and place dependent interactions that characterized communication throughout most of human history. ICTs have extended human interaction and increased our interconnectedness, making it possible for geographically dispersed people not only to share information at an ever-faster rate but also to organize and to take action in response to events occurring in places far from where they are physically situated.

While these complex webs of connections can facilitate positive collective action, they can also put us at risk. As TED speaker Ian Goldin observes, the complexity of our global connections creates a built-in fragility: What happens in one part of the world can very quickly affect everyone, everywhere.

The proliferation of ICTs and the new webs of social connections they engender have had profound political implications for governments, citizens, and non-state actors alike. Each of the TEDTalks featured in this course explore some of these implications, highlighting the connections and tensions between technology and politics. Some speakers focus primarily on how anti-authoritarian protesters use technology to convene and organize supporters, while others expose how authoritarian governments use technology to manipulate and control individuals and groups. When viewed together as a unit, the contrasting voices reveal that technology is a contested site through which political power is both exercised and resisted.

Technology as liberator

The liberating potential of technology is a powerful theme taken up by several TED speakers in Cyber-Influence and Power . Journalist and Global Voices co-founder Rebecca MacKinnon, for example, begins her talk by playing the famous Orwell-inspired Apple advertisement from 1984. Apple created the ad to introduce Macintosh computers, but MacKinnon describes Apple's underlying narrative as follows: "technology created by innovative companies will set us all free." While MacKinnon examines this narrative with a critical eye, other TED speakers focus on the ways that ICTs can and do function positively as tools of social change, enabling citizens to challenge oppressive governments.

In a 2011 CNN interview, Egyptian protest leader, Google executive, and TED speaker Wael Ghonim claimed "if you want to free a society, just give them internet access. The young crowds are going to all go out and see and hear the unbiased media, see the truth about other nations and their own nation, and they are going to be able to communicate and collaborate together." (i). In this framework, the opportunities for global information sharing, borderless communication, and collaboration that ICTs make possible encourage the spread of democracy. As Ghonim argues, when citizens go online, they are likely to discover that their particular government's perspective is only one among many. Activists like Ghonim maintain that exposure to this online free exchange of ideas will make people less likely to accept government propaganda and more likely to challenge oppressive regimes.

A case in point is the controversy that erupted around Khaled Said, a young Egyptian man who died after being arrested by Egyptian police. The police claimed that Said suffocated when he attempted to swallow a bag of hashish; witnesses, however, reported that he was beaten to death by the police. Stories about the beating and photos of Said's disfigured body circulated widely in online communities, and Ghonim's Facebook group, titled "We are all Khaled Said," is widely credited with bringing attention to Said's death and fomenting the discontent that ultimately erupted in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, or what Ghonim refers to as "revolution 2.0."

Ghonim's Facebook group also illustrates how ICTs enable citizens to produce and broadcast information themselves. Many people already take for granted the ability to capture images and video via handheld devices and then upload that footage to platforms like YouTube. As TED speaker Clay Shirky points out, our ability to produce and widely distribute information constitutes a revolutionary change in media production and consumption patterns. The production of media has typically been very expensive and thus out of reach for most individuals; the average person was therefore primarily a consumer of media, reading books, listening to the radio, watching TV, going to movies, etc. Very few could independently publish their own books or create and distribute their own radio programs, television shows, or movies. ICTs have disrupted this configuration, putting media production in the hands of individual amateurs on a budget — or what Shirky refers to as members of "the former audience" — alongside the professionals backed by multi-billion dollar corporations. This "democratization of media" allows individuals to create massive amounts of information in a variety of formats and to distribute it almost instantly to a potentially global audience.

Shirky is especially interested in the Internet as "the first medium in history that has native support for groups and conversations at the same time." This shift has important political implications. For example, in 2008 many Obama followers used Obama's own social networking site to express their unhappiness when the presidential candidate changed his position on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. The outcry of his supporters did not force Obama to revert to his original position, but it did help him realize that he needed to address his supporters directly, acknowledging their disagreement on the issue and explaining his position. Shirky observes that this scenario was also notable because the Obama organization realized that "their role was to convene their supporters but not to control their supporters." This tension between the use of technology in the service of the democratic impulse to convene citizens vs. the authoritarian impulse to control them runs throughout many of the TEDTalks in Cyber-Influence and Power.

A number of TED speakers explicitly examine the ways that ICTs give individual citizens the ability to document governmental abuses they witness and to upload this information to the Internet for a global audience. Thus, ICTs can empower citizens by giving them tools that can help keep their governments accountable. The former head of Al Jazeera and TED speaker Wadah Khanfar provides some very clear examples of the political power of technology in the hands of citizens. He describes how the revolution in Tunisia was delivered to the world via cell phones, cameras, and social media outlets, with the mainstream media relying on "citizen reporters" for details.

Former British prime minister Gordon Brown's TEDTalk also highlights some of the ways citizens have used ICTs to keep their governments accountable. For example, Brown recounts how citizens in Zimbabwe used the cameras on their phones at polling places in order to discourage the Mugabe regime from engaging in electoral fraud. Similarly, Clay Shirky begins his TEDTalk with a discussion of how cameras on phones were used to combat voter suppression in the 2008 presidential election in the U.S. ICTs allowed citizens to be protectors of the democratic process, casting their individual votes but also, as Shirky observes, helping to "ensure the sanctity of the vote overall."

Technology as oppressor

While smart phones and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook have arguably facilitated the overthrow of dictatorships in places like Tunisia and Egypt, lending credence to Gordon Brown's vision of technology as an engine of liberalism and pluralism, not everyone shares this view. As TED speaker and former religious extremist Maajid Nawaz points out, there is nothing inherently liberating about ICTs, given that they frequently are deployed to great effect by extremist organizations seeking social changes that are often inconsistent with democracy and human rights. Where once individual extremists might have felt isolated and alone, disconnected from like-minded people and thus unable to act in concert with others to pursue their agendas, ICTs allow them to connect with other extremists and to form communities around their ideas, narratives, and symbols.

Ian Goldin shares this concern, warning listeners about what he calls the "two Achilles heels of globalization": growing inequality and the fragility that is inherent in a complex integrated system. He points out that those who do not experience the benefits of globalization, who feel like they've been left out in one way or another, can potentially become incredibly dangerous. In a world where what happens in one place very quickly affects everyone else — and where technologies are getting ever smaller and more powerful — a single angry individual with access to technological resources has the potential to do more damage than ever before. The question becomes then, how do we manage the systemic risk inherent in today's technology-infused globalized world? According to Goldin, our current governance structures are "fossilized" and ill-equipped to deal with these issues.

Other critics of the notion that ICTs are inherently liberating point out that ICTs have been leveraged effectively by oppressive governments to solidify their own power and to manipulate, spy upon, and censor their citizens. Journalist and TED speaker Evgeny Morozov expresses scepticism about what he calls "iPod liberalism," or the belief that technology will necessarily lead to the fall of dictatorships and the emergence of democratic governments. Morozov uses the term "spinternet" to describe authoritarian governments' use of the Internet to provide their own "spin" on issues and events. Russia, China, and Iran, he argues, have all trained and paid bloggers to promote their ideological agendas in the online environment and/or or to attack people writing posts the government doesn't like in an effort to discredit them as spies or criminals who should not be trusted.

Morozov also points out that social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter are tools not only of revolutionaries but also of authoritarian governments who use them to gather open-source intelligence. "In the past," Morozov maintains, "it would take you weeks, if not months, to identify how Iranian activists connect to each other. Now you know how they connect to each other by looking at their Facebook page. KGB...used to torture in order to get this data." Instead of focusing primarily on bringing Internet access and devices to the people in countries ruled by authoritarian regimes, Morozov argues that we need to abandon our cyber-utopian assumptions and do more to actually empower intellectuals, dissidents, NGOs and other members of society, making sure that the "spinternet" does not prevent their voices from being heard.

The ICT Empowered Individual vs. The Nation State

In her TEDTalk "Let's Take Back the Internet," Rebecca MacKinnon argues that "the only legitimate purpose of government is to serve citizens, and…the only legitimate purpose of technology is to improve our lives, not to manipulate or enslave us." It is clearly not a given, however, that governments, organizations, and individuals will use technology benevolently. Part of the responsibility of citizenship in the globalized information age then is to work to ensure that both governments and technologies "serve the world's peoples." However, there is considerable disagreement about what that might look like.

WikiLeaks spokesperson and TED speaker Julian Assange, for example, argues that government secrecy is inconsistent with democratic values and is ultimately about deceiving and manipulating rather than serving the world's people. Others maintain that governments need to be able to keep secrets about some topics in order to protect their citizens or to act effectively in response to crises, oppressive regimes, terrorist organizations, etc. While some view Assange's use of technology as a way to hold governments accountable and to increase transparency, others see this use of technology as a criminal act with the potential to both undermine stable democracies and put innocent lives in danger.

ICTs and global citizenship

While there are no easy answers to the global political questions raised by the proliferation of ICTs, there are relatively new approaches to the questions that look promising, including the emergence of individuals who see themselves as global citizens — people who participate in a global civil society that transcends national boundaries. Technology facilitates global citizens' ability to learn about global issues, to connect with others who care about similar issues, and to organize and act meaningfully in response. However, global citizens are also aware that technology in and of itself is no panacea, and that it can be used to manipulate and oppress.

Global citizens fight against oppressive uses of technology, often with technology. Technology helps them not only to participate in global conversations that affect us all but also to amplify the voices of those who have been marginalized or altogether missing from such conversations. Moreover, global citizens are those who are willing to grapple with large and complex issues that are truly global in scope and who attempt to chart a course forward that benefits all people, regardless of their locations around the globe.

Gordon Brown implicitly alludes to the importance of global citizenship when he states that we need a global ethic of fairness and responsibility to inform global problem-solving. Human rights, disease, development, security, terrorism, climate change, and poverty are among the issues that cannot be addressed successfully by any one nation alone. Individual actors (nation states, NGOs, etc.) can help, but a collective of actors, both state and non-state, is required. Brown suggests that we must combine the power of a global ethic with the power to communicate and organize globally in order for us to address effectively the world's most pressing issues.

Individuals and groups today are able to exert influence that is disproportionate to their numbers and the size of their arsenals through their use of "soft power" techniques, as TED speakers Joseph Nye and Shashi Tharoor observe. This is consistent with Maajid Nawaz's discussion of the power of symbols and narratives. Small groups can develop powerful narratives that help shape the views and actions of people around the world. While governments are far more accustomed to exerting power through military force, they might achieve their interests more effectively by implementing soft power strategies designed to convince others that they want the same things. According to Nye, replacing a "zero-sum" approach (you must lose in order for me to win) with a "positive-sum" one (we can both win) creates opportunities for collaboration, which is necessary if we are to begin to deal with problems that are global in scope.

Let's get started

Collectively, the TEDTalks in this course explore how ICTs are used by and against governments, citizens, activists, revolutionaries, extremists, and other political actors in efforts both to preserve and disrupt the status quo. They highlight the ways that ICTs have opened up new forms of communication and activism as well as how the much-hailed revolutionary power of ICTs can and has been co-opted by oppressive regimes to reassert their control.

By listening to the contrasting voices of this diverse group of TED speakers, which includes activists, journalists, professors, politicians, and a former member of an extremist organization, we can begin to develop a more nuanced understanding of the ways that technology can be used both to facilitate and contest a wide variety of political movements. Global citizens who champion democracy would do well to explore these intersections among politics and technology, as understanding these connections is a necessary first step toward MacKinnon's laudable goal of building a world in which "government and technology serve the world's people and not the other way around."

Let's begin our exploration of the intersections among politics and technology in today's globalized world with a TEDTalk from Ian Goldin, the first Director of the 21st Century School, Oxford University's think tank/research center. Goldin's talk will set the stage for us, exploring the integrated, complex, and technology rich global landscape upon which the political struggles for power examined by other TED speakers play out.

Navigating our global future

i. "Welcome to Revolution 2.0, Ghonim Says," CNN, February 9, 2011. http://www.cnn.com/video/?/video/world/2011/02/09/wael.ghonim.interview.cnn .

Relevant talks

Gordon Brown

Wiring a web for global good.

Clay Shirky

How social media can make history.

Wael Ghonim

Inside the egyptian revolution.

Wadah Khanfar

A historic moment in the arab world.

Evgeny Morozov

How the net aids dictatorships.

Maajid Nawaz

A global culture to fight extremism.

Rebecca MacKinnon

Let's take back the internet.

Julian Assange

Why the world needs wikileaks.

Global power shifts

Shashi Tharoor

Why nations should pursue soft power.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

democracy summary

Understand the meaning and types of democracy.

democracy , Form of government in which supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodic free elections. In a direct democracy, the public participates in government directly (as in some ancient Greek city-state s, some New England town meetings, and some cantons in modern Switzerland). Most democracies today are representative. The concept of representative democracy arose largely from ideas and institutions that developed during the European Middle Ages and the Enlightenment and in the American and French Revolutions. Democracy has come to imply universal suffrage, competition for office, freedom of speech and the press, and the rule of law. See also republic.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.1: What is Democracy?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135838

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define democracy.

- Recognize the origins and characteristics of democracies.

- Distinguish between (the) types of democracy.

Introduction

“Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…” — Winston Churchill, November 11th, 1947

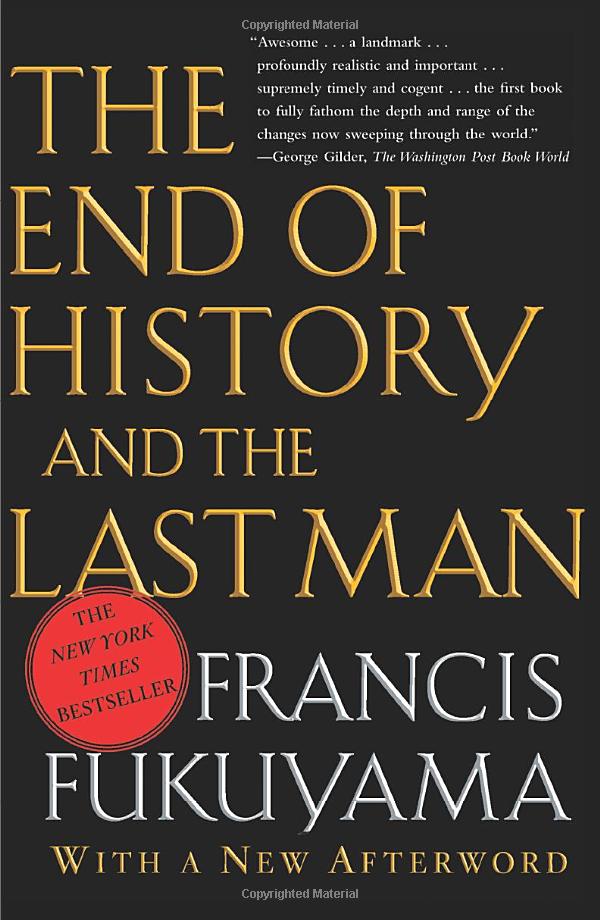

More than half of the governments currently in existence operate under some variation of democracy. The global trends towards democratization worldwide during the twentieth century prompted some to conclude that democracy is simply the best, or most ideal, form of government. Indeed, near the end of the twentieth century, political scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote a book entitled, The End of History and the Last Man , where he argued humanity had reached the end of history because many countries had adopted forms of liberal democracy. His book was a best-seller which energized many about the prospects of a world which embraces democracy and will not again suffer the likes of major World Wars and conflicts. Twenty years after this publication, however, and in light of events like the September 11th attacks on the United States, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the rise of China, the backsliding of Russia, the COVID-19 pandemic and the eventual fall of Afghanistan back to authoritarian rule, Fukuyama mostly retracted his conclusion that the world had accepted democracy as the standard. Instead, he now asserts that issues related to political identity now threaten the security of geo-political stability. The many challenges facing democracy, democratization, and democratic backsliding (discussed in Chapter 5), prompts us to take a hard look at democracy, its types, its institutions and models, and various manifestations throughout the world. Is democracy the best form of government? What are its advantages and disadvantages?

Francis Fukuyama is an American Political Scientist, economist, and author of books and journal articles. From left to right, his 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, prompted discussion over whether the world had reached the end of history because so many countries had been adopting liberal democracy as their form of government. One of his more recent books, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, came out in 2018, and his conclusions began veering away from the belief that the world had accepted liberal democracy. Instead, political identity and the weight of historical disputes potentially impede global geopolitical potential for long-term peace.

Origins, Definitions and Characteristics of Democracy

Although there is evidence of what anthropologists have designated primitive democracy , wherein small communities have face-to-face discussions in order to make decisions, as far back as 2,500 years ago, the first formal application of democratic institutions and processes is generally attributed to ancient Greece. Athens, Greece is generally credited with being the birthplace of democracy. In its simplest terms, democracy is a government system in which the supreme power of government is vested in the people. Democracy comes from the Greek word, dēmokratiā, where “demos” means “people”, and “kratos” meaning “power” or “rule.” Prior to the formation of legal reforms, Athens had operated as an aristocracy.

An aristocracy is a form of government where power is held by nobility or those concerned to be of the highest classes within a society. Aristocracy proved troublesome for Athens, and the people eventually rallied under an Athenian leader named Solon (circa 640 - 560 B.C.E.). In trying to meet the demands of the people, Solon attempted to satisfy all classes of the Athenian population, rich and poor alike, to devise a form of government which satisfied all. To this end, in 594 B.C.E., Solon created legal reforms and a constitution, which provided the foundations for citizen participation in government affairs, and abolished slavery of Athenian citizens. Under this construct, adult males who had completed their military training were given the right to vote, and as much as 20% of the population was considered to be active in making laws. Eventually, democracy in Athens failed, due to both internal and external factors. Internally, there was heavy criticism that the aristocracy was still in force, and able to pervert and manipulate legal outcomes to their own benefit. Further, the works of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, all of whom were critical of the merits and feasibility of democracy, led to the erosion of trust in democracy in Athens. Generally, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, though they had their own unique critiques of democracy, tended to value political stability over the potential of “rule of the mob.” Externally, and tied to the prospect of political stability, Athens faced frequent challenges to its democracy from the outside. The Peloponnesian War, the changes in leadership from King Phillip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great, and finally, the rise of the Roman Empire, all are also attributed to the eventual decline of democracy in ancient Greece. After the fall of democracy in Greece, the prospect of democracy did not re-emerge as a feasible, or even desired, option until the early modern era in the 1600s.

Ancient concepts and manifestations of democracy differ greatly from modern conceptualization and application of democracy. One of the key differences is in the way power from the people is channeled; the difference becomes apparent in comparing a direct democracy versus an indirect democracy. A direct democracy enables citizens to vote directly, or participate directly, in the formation of laws, public policy and government decisions. In this system, citizens personally get involved in all aspects of politics, and are able to change constitutional laws, recommend referendums and make suggestions for laws, and mandate the activities and actions of government officials. To some extent, Athens exercised a direct democracy in that adult male citizens, who had completed their military training, could participate directly in the making of laws. It was not a 'perfect' democracy in that not all citizens, male and female, rich and poor, could participate, but it did have a mechanism for a certain class of citizen participating, i.e. males. In contrast, indirect democracy channels the power of the people through representation, where citizens elect representatives to make laws and government decisions on their behalf. In this scenario, citizens of the country are granted suffrage , which is the right to vote in political elections and propose referendums. In a healthy democracy, elections are both free and fair . Free elections are those where all citizens are able to vote for the candidate of their choice. The election is free if all citizens who meet the requirements to vote (e.g. are of lawful age and meet the citizenship requirements, if they exist), are not prevented from participating in the election process. Fair elections are those in which all votes carry equal weight, are counted accurately, and the election results are able to be accepted by parties. Ideally, the following standards are met to ensure elections are free and fair:

Before the Election

- Eligible citizens are able to register to vote;

- Voters are given access to reliable information about the ballot and the elections;

- Citizens are able to run for office.

During the Election

- All voters have access to a polling station or some method of casting their vote;

- Voters are able to vote free from intimidation;

- The voting process is free of fraud and tampering.

After the Election

- Ballots are accurately counted and the results are announced;

- The results of the election are accepted / respected / honored.

The integrity of the election is of paramount importance in democracies, for if the process is not found to be free or fair, it violates the core principles of what constitutes a democracy: by the people, for the people.

Indirect democracy is what most democratic countries today practice, partly because of logistics (In the U.S., how would every single adult citizen directly participate in the making of laws? Would requiring a vote for every decision be time efficient?), and to another extent, a question over whether voting is always the best option for determining just, equitable or ideal outcomes. In a representative democracy, citizens, to some extent, outsource the power of lawmaking to those who, ideally, either have expertise in making laws or who may be granted a greater depth of information in order to make decisions.In this sense, not every citizen necessarily wants to be involved in every government decision, but would prefer selecting a representative to getting political work done. Further, although most democratic countries do practice indirect democracy, there are often some mechanisms that align with some characteristics of a direct democracy. For instance, the U.S. has a representative democracy, but voters in some states have the ability to put forth initiatives and referendums, also referred to as Ballot Propositions. Overall, democracy’s definition, if practiced as indirect democracy, can be understood as: a government system in which the supreme power of the government is vested in the people, and exercised by the people through a system of representation which includes the continued practice of holding free and fair elections.

Importantly, democracy has a number of characteristics which can be central to understanding the variation in democracies that exist worldwide today. These differences also highlight the difference between concepts of ancient democracy versus contemporary democracy. Ancient democracy had no concept or foundations for widespread suffrage or the protection of civil liberties. Some of these modern accepted democratic themes include (but are not limited to): free, fair and regular elections (ideally, with the inclusion of more than one viable political party), respect for civil liberties (freedom of religion, speech, the press, peaceful assembly; freedom to criticize the government) as well as the protection of civil rights (freedom from discrimination based on various characteristics deemed important in society). Democracies which not only facilitate free and fair elections, but also ensure the protection of civil liberties are called liberal democracies . Although these are the general themes, there is still ample debate among scholars about the importance and weight of these characteristics. Larry Diamond, an American political sociologist and a scholar of democratic studies, put forth the following four characteristics which make a democracy, a democracy. A democracy must include:

- A system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections;

- Active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life;

- The protection of human rights of all citizens;

- A rule of law in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens. (Diamond 2004)

Karl Popper, an Austrian-British academic and philosopher (whom you may recognize from Chapter 2 for his work on the nature of inquiry and the recognition of falsification theory), had a more blunt definition for democracy, “I personally call the type of government which can be removed without violence ‘democracy,’ and the other, ‘tyranny.’ (Popper 2002). Instead of citing specific characteristics of democracy, which Popper was hesitant to do given the wide variation in democracies that exist, he simply contrasted it with outright tyranny. In general, Popper emphasized the importance not in how the people could exercise authority, but that they have access, availability and opportunity, through some means, to control their leaders without violence, retribution or revolution.

Other scholars have noted more rigid qualifications for democracy. In looking at the world of Robert Dahl, Ian Shapiro and Jose Antonio Cheibub, all political scientists, they assert that every vote in a representative democracy must carry equal weight, and that the rights of citizens must be equally protected by a well-defined and clear “law of the land;” in most cases, the “law of the land,” rests with a written constitution. The rights and liberties of citizens must be protected by the law of the land. (Dahl, Shapiro, Cheibub, 2003)

Overall, there are hundreds of critiques and frameworks for defining democracies and noting its characteristics, and scholars are generally not in full agreement on what constitutes a perfect democracy. Nevertheless, reaching some consensus on the characteristics is important if scholars want to advance the understanding of regime types like democracy. The difference in perception of democracy can be seen in how some organizations choose to measure democracy across countries. At present, there are at least eight organizations which attempt to quantify the existence and health of democracies worldwide. These eight include: Freedom House, Economist Intelligence Unit, V-Dem, the Human Freedom Index, Polity IV, World Governance Indicators, Democracy Barometer, and Vanhanen’s Polyarchy Index. In Table 4.1.1, a few of these are highlighted based on what they identify as main characteristics of democracy. This table shows the differences in components considered when trying to measure democracy. From left to right, Freedom House, Economist Intelligence Unit, and Varieties of Democracy; all are organizations which attempt to determine whether countries are democratic and assess the strength of their democratic institutions.

Table 4.1.1 : Measuring Democracy

| Index | Freedom House | Economist Intelligence Unit | Varieties of Democracy |

| Components/ Characteristics Measured | -Elections -Participation -Functioning of Government -Free Expression -Organizational Rights -Rule of Law -Individual Rights | -Elections -Participation -Functioning of Government -Political Culture -Civil Liberties | -Elections -Participation -Deliberation -Egalitarianism -Individual Rights |

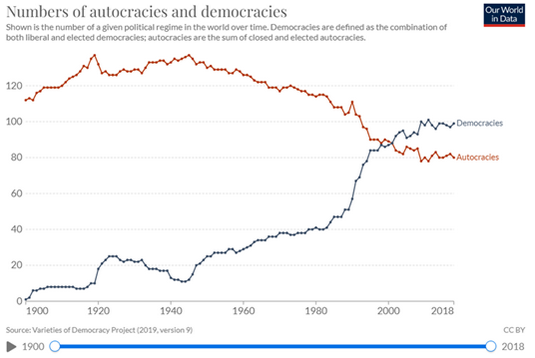

The different organizations, choosing different areas of emphasis and weight for characteristics of democracy, yield different outcomes in terms of identifying whether a country is a democracy, as well as judging the healthiness of a democracy. For instance, as of 2018, the Varieties of Democracies Project finds there are currently 99 democracies, and 80 autocracies. Autocracies are forms of government where countries are ruled either by a single person or group, who/which holds total power and control. For this same time-period, the Polity IV Index disagrees, finding 57 full democracies, 28 mixed-regime types, and 13 autocratic regimes. Importantly, the Polity IV Index does not take suffrage into consideration as a meaningful indicator of democracy. Freedom House also arrives at different outcomes for this same time-period, asserting that 86 countries are democracies, with 109 non-democracies. Finally, the Economist Intelligence Unit found 20 countries to be fully democratic, and 55 countries have “flawed democracies.” Given that scholars and these organizations have acknowledged that different types of democracies exist, it is now useful to discuss these types, as well as the implications for these types on the institution of democracy.

The number of democracies has significantly grown worldwide since 1900. Political scientists have sometimes called jumps in the number of democracies ‘waves.’ In this way, there have been three major waves of democratization: World War I (First wave, 1828-1926), with subsequent “waves” of democratization coming following World War II (Second wave) and the democratic transitions in Portugal, Spain and Latin American in the 1970s (Third wave).

Types of Democracy

The different organizations, choosing different areas of emphasis and weight for characteristics of democracy, yield different outcomes in terms of identifying whether a country is a democracy, as well as judging the healthiness of a democracy. For instance, as of 2018, the Varieties of Democracies Project finds there are currently 99 democracies, and 80 autocracies. Recall, autocracies are forms of government where countries are ruled either by a single person or group, who/which holds total power and control. For this same time-period, the Polity IV Index disagrees, finding 57 full democracies, 28 mixed-regime types, and 13 autocratic regimes. Importantly, the Polity IV Index does not take suffrage into consideration as a meaningful indicator of democracy. Freedom House also arrives at different outcomes for this same time-period, asserting that 86 countries are democracies, with 109 non-democracies. Finally, the Economist Intelligence Unit found 20 countries to be fully democratic, and 55 countries have “flawed democracies.” Given that scholars and these organizations have acknowledged that different types of democracies exist, it is now useful to discuss these types, as well as the implications for these types on the institution of democracy.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Democracy Essay for Students in English

Essay on Democracy

Introduction.

Democracy is mainly a Greek word which means people and their rules, here peoples have the to select their own government as per their choice. Greece was the first democratic country in the world. India is a democratic country where people select their government of their own choice, also people have the rights to do the work of their choice. There are two types of democracy: direct and representative and hybrid or semi-direct democracy. There are many decisions which are made under democracies. People enjoy few rights which are very essential for human beings to live happily.

Our country has the largest democracy. In a democracy, each person has equal rights to fight for development. After the independence, India has adopted democracy, where the people vote those who are above 18 years of age, but these votes do not vary by any caste; people from every caste have equal rights to select their government. Democracy, also called as a rule of the majority, means whatever the majority of people decide, it has to be followed or implemented, the representative winning with the most number of votes will have the power. We can say the place where literacy people are more there shows the success of the democracy even lack of consciousness is also dangerous in a democracy. Democracy is associated with higher human accumulation and higher economic freedom. Democracy is closely tied with the economic source of growth like education and quality of life as well as health care. The constituent assembly in India was adopted by Dr B.R. Ambedkar on 26 th November 1949 and became sovereign democratic after its constitution came into effect on 26 January 1950.

What are the Challenges:

There are many challenges for democracy like- corruption here, many political leaders and officers who don’t do work with integrity everywhere they demand bribes, resulting in the lack of trust on the citizens which affects the country very badly. Anti-social elements- which are seen during elections where people are given bribes and they are forced to vote for a particular candidate. Caste and community- where a large number of people give importance to their caste and community, therefore, the political party also selects the candidate on the majority caste. We see wherever the particular caste people win the elections whether they do good for the society or not, and in some cases, good leaders lose because of less count of the vote.

India is considered to be the largest democracy around the globe, with a population of 1.3 billion. Even though being the biggest democratic nation, India still has a long way to becoming the best democratic system. The caste system still prevails in some parts, which hurts the socialist principle of democracy. Communalism is on the rise throughout the globe and also in India, which interferes with the secular principle of democracy. All these differences need to be set aside to ensure a thriving democracy.

Principles of Democracy:

There are mainly five principles like- republic, socialist, sovereign, democratic and secular, with all these quality political parties will contest for elections. There will be many bribes given to the needy person who require food, money, shelter and ask them to vote whom they want. But we can say that democracy in India is still better than the other countries.

Basically, any country needs democracy for development and better functioning of the government. In some countries, freedom of political expression, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, are considered to ensure that voters are well informed, enabling them to vote according to their own interests.

Let us Discuss These Five Principles in Further Detail

Sovereign: In short, being sovereign or sovereignty means the independent authority of a state. The country has the authority to make all the decisions whether it be on internal issues or external issues, without the interference of any third party.

Socialist: Being socialist means the country (and the Govt.), always works for the welfare of the people, who live in that country. There should be many bribes offered to the needy person, basic requirements of them should be fulfilled by any means. No one should starve in such a country.

Secular: There will be no such thing as a state religion, the country does not make any bias on the basis of religion. Every religion must be the same in front of the law, no discrimination on the basis of someone’s religion is tolerated. Everyone is allowed to practice and propagate any religion, they can change their religion at any time.

Republic: In a republic form of Government, the head of the state is elected, directly or indirectly by the people and is not a hereditary monarch. This elected head is also there for a fixed tenure. In India, the head of the state is the president, who is indirectly elected and has a fixed term of office (5 years).

Democratic: By a democratic form of government, means the country’s government is elected by the people via the process of voting. All the adult citizens in the country have the right to vote to elect the government they want, only if they meet a certain age limit of voting.

Merits of Democracy:

better government forms because it is more accountable and in the interest of the people.

improves the quality of decision making and enhances the dignity of the citizens.

provide a method to deal with differences and conflicts.

A democratic system of government is a form of government in which supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodic free elections. It permits citizens to participate in making laws and public policies by choosing their leaders, therefore citizens should be educated so that they can select the right candidate for the ruling government. Also, there are some concerns regarding democracy- leaders always keep changing in democracy with the interest of citizens and on the count of votes which leads to instability. It is all about political competition and power, no scope for morality.

Factors Affect Democracy:

capital and civil society

economic development

modernization

Norway and Iceland are the best democratic countries in the world. India is standing at fifty-one position.

India is a parliamentary democratic republic where the President is head of the state and Prime minister is head of the government. The guiding principles of democracy such as protected rights and freedoms, free and fair elections, accountability and transparency of government officials, citizens have a responsibility to uphold and support their principles. Democracy was first practised in the 6 th century BCE, in the city-state of Athens. One basic principle of democracy is that people are the source of all the political power, in a democracy people rule themselves and also respect given to diverse groups of citizens, so democracy is required to select the government of their own interest and make the nation developed by electing good leaders.

FAQs on Democracy Essay for Students in English

1. What are the Features of Democracy?

Features of Democracy are as follows

Equality: Democracy provides equal rights to everyone, regardless of their gender, caste, colour, religion or creed.

Individual Freedom: Everybody has the right to do anything they want until it does not affect another person’s liberty.

Majority Rules: In a democracy, things are decided by the majority rule, if the majority agrees to something, it will be done.

Free Election: Everyone has the right to vote or to become a candidate to fight the elections.

2. Define Democracy?

Democracy means where people have the right to choose the rulers and also people have freedom to express views, freedom to organise and freedom to protest. Protesting and showing Dissent is a major part of a healthy democracy. Democracy is the most successful and popular form of government throughout the globe.

Democracy holds a special place in India, also India is still the largest democracy in existence around the world.

3. What are the Benefits of Democracy?

Let us discuss some of the benefits received by the use of democracy to form a government. Benefits of democracy are:

It is more accountable

Improves the quality of decision as the decision is taken after a long time of discussion and consultation.

It provides a better method to deal with differences and conflicts.

It safeguards the fundamental rights of people and brings a sense of equality and freedom.

It works for the welfare of both the people and the state.

4. Which country is the largest democracy in the World?

India is considered the largest democracy, all around the world. India decided to have a democratic Govt. from the very first day of its independence after the rule of the British. In India, everyone above the age of 18 years can go to vote to select the Government, without any kind of discrimination on the basis of caste, colour, religion, gender or more. But India, even being the largest democracy, still has a long way to become perfect.

5. Write about the five principles of Democracy?

There are five key principles that are followed in a democracy. These Five Principles of Democracy of India are - secular, sovereign, republic, socialist, and democratic. These five principles have to be respected by every political party, participating in the general elections in India. The party which got the most votes forms the government which represents the democratic principle. No discrimination is done on the basis of religion which represents the secular nature of democracy. The govt. formed after the election has to work for the welfare of common people which shows socialism in play.

Democratic Governance Concept Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Plan of action to consolidate and spread the values of democratic governance.

Democratic governance is based on legitimacy, order, stability, accountability, and transparency. It mainly involves promoting durable governance; this includes introducing of politics participation, a stable society, and freedom of media. In addition, democratic governance promotes the involvement of women and other minority groups in government levels and in society levels as well. Democratic governance also involves working hard to ensure that children’s rights and human rights are in place and followed to the later. A state that practices democratic governance establishes policies that are sustainable beyond government changes, which are capable of resolving any conflicts within the state in an orderly and legal manner.

These policies should be imposed in the right manner and are capable of fighting corruption and dictatorship; indeed, in a democratic state, criticism should not be shunned by the government (Frank, 1992). Most countries globally try to exercise democratic governance especially to curb poverty. Some of the non-governmental organizations that contribute to the democratic governance include the United Nations development programme, which promotes participation, and effectiveness in member countries.

Such organizations assist countries to improve on their justice levels and the public administration. However, “good governance should be democratic in both an institutional and social sense; it should also include individual liberties, human rights, economic progress, and social justice” (Carty, n.d, pp 2). The presence of United States military in Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan represent a democratic future, since these troops promote peace and harmony in the three countries. It is through the peaceful environment that the United States government is able to promote governance in such countries, thus helping the country to recover by promoting peace, reviving the country’s economy, as well as creating a democratic government.

According to Morgan (2011), “united states is fighting three wars, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, while struggling under huge budget deficit and national debt.” The United States proves to be a main player in the promotion of democratic governance in countries where conflict dictatorship and war is involved. In this case, the US has used millions of dollars in order to sustain the troops based in Iraq; this has however met critics from the US citizen, who argue that such money should be invested in their country for development purposes, rather than in the war hit countries. For instance, the United States is spending almost $550 for the military operations in Libya alone, which is a large sum of cash that could be utilized to other major issues of development in the US.

However, the United States president noted that, if the US military was to overthrow the current Libyan president, Gadaffi, by force, this would only mean that the military lives would be endangered, which should not be the case. The Afghanistan military operation for a year cost $110 billion, meaning that approximately $300 million is used in a day. In addition, in 2008, Iraq military operation cost the United States approximately, $ 140 billion, which adds up to $383 million in a day. However, this year there is a reduction of the troops sent to Iraq, which will be approximately 100,000, hence a reduction in salaries, health costs and allowances. However, this is a wise decision since the United States is incurring a large sum of dollars on the many troops it posts to Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan, of which these huge sums of money could have been used on development programmes in the United States (Morgan, 2011).

The current situation in Libya entails the United States first priority to be protecting the Libyan citizens by eliminating any threats to the lives of the innocent civilians. The US government has however declared that Libya is a no fly zone and has put in place diplomatic and political tools. They have also freezed president Gadaffi’s assets, this are some of the strategies that the US hopes that will lead to the stepping down of Gaddafi. However, one of the fundamental values that the United States government has applied in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya is the protection of innocent human life by ensuring that they do not make any drastic decision that may comprise the lives of civilians. Such actions by the United States enhance democratic governance.

The right to democracy is the right for people to participate and to be consulted in the process of making political choices (Frank, 1994, pp 73). In fact, the United States government has tried to practice democratic governance as a way of solving conflict in war-torn and conflict-hit countries. Though these involvements have cost the United States a fortune, some fruits have been yielded due to these engagements. Democratic governance however cannot work without its values; hence, it is appropriate for the adoption of values in any governance.

The United States should hence involve the non- profitable and non-governmental institution in its journey to effective governance. Such institutions may include, the United Nations development programme (UNDP), which supports and promotes human rights by supporting programmes aimed at building institutions, promoting and protecting human rights, and engaging in human right practices in member nations. UNDP provides support, advice, and guidance tools, when dealing with the governments that are interested in promoting human rights.

According to the Africa – EU partnership, another human rights organization, on the issue of democratic governance and human rights (2011), its main aim is to work with countries and implement programmes that tackle corruption, prevent torture, and promote human rights. This partnership enhances the promotion of human rights by funding projects that are geared towards protecting innocent lives globally. In addition, it also focuses on promoting awareness of the African peer mechanism and supporting the African charter on democracy, elections, and ethics. However, “a good government is associated with democratic governance in that strong institutions help legitimate and strengthen the system they serve and strengthen; functioning democracy helps provide the transparency and accountability to enable government to be more relevant and attendant to the society” (Carty, n.d, pp 4).

According to Sen. A, (1999, pp 6), there are various functions of democracy; first, countries that practice democracy have the political freedom which results to human freedom. Democracy ensure that both civil and political rights are exercised, thus promoting social lives of citizens of a particular country. In addition, democracy promotes the listening of citizen’s claims and agendas regarding their political views. Democracy also promotes socialization in a society such that, citizens of a particular country are able to learn from each other, hence enabling the society to be able to create its values and major priorities.

In addition, the main plan of action that should be implemented in order to consolidate and spread the values of democratic governance should involve the United States working hand in hand with non-governmental organizations like the United Nations and European Union in supporting and promoting human right initiative and programmes. In addition, the national democratic institute (NDI) is another non- profitable organization, which is geared towards working with democratic institutions globally on improving the lives of citizens through citizen’s participation, openness, and accountability. While working together with such organizations, there is a possibility for the enactment of democratic governance to be fast and effective, and this plan will save on the many millions that United States is spending on its military troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya.

Secondly, the United States should find other means of promoting the democratic governance in the war-affected areas, apart from sending its military troops to life-risking missions. The United States can try to hold peace talks with the affected countries’ representatives and find measure that will curb conflicts and ruthless leadership. Implementing human rights institutions in different countries could also help in solving problems of bad governance. Since these institutions will act as a link between the United States government and the affected countries, this will be an effective method of ensuring that democratic governance is practiced to the fullest. The main aim of democratic governance is to enhance effective leadership of a country by curbing dictatorship and promoting peace, enhancing political freedom and promoting human rights of all citizens of a state.

Democratic governance is a process that involves participation of both the government of a state and the citizens of that state. In a democratic state, issues of dictatorship and misuse of power are rare. The government normally concentrates on welfare of its citizen, ensuring that human rights policies are implemented and followed. However, in war-hit areas, democratic governance may be promoted by major countries such as the United States, which send its troops to these countries to promote peace and protect the lives of innocent citizens of the affected countries. United States is however spending billions of dollars in trying to promote peace in countries like Libya, Afghanistan, and Iraq. However, too much involvement of the United States to these countries is costing the country in terms of money and its own development, rather than focusing on issues such as education, health, and poverty.

Nevertheless, democratic governance can be promoted in the affected countries by cooperation between the United States, the great seven nations, and the non-governmental organizations like the United Nations. Finally, it is important to note that the democratic governance of any country involves citizens of that country and its government respectively. A nation which has good governance should be capable of promoting peace throughout its territories, support and promote human rights of its citizens, and ensure that there is room for its citizen’s expression in terms of politics. The right of speech and media press should also be encouraged by the government but not shunned, as a good democratic nation always listens to its citizens, and sometimes, uses those critics to govern and lead the country in a better way.

Carty, W. and Rizvi, G. (N. D). The Legitimacy Challenge for Good Government and Democratic Governance: The Imperative to Innovate. Web.

Democratic Governance . (N.d). National democratic institute (NDI). Web.

Democratic governance and human rights. (2011). African and Europe Partnership. Web.

Frank, T. (1994). Democracy as a human right . Web.

Frank, T. (1992). The Emerging Right to Democratic Governance. The American Journal of International Law , Vol. 86, No. 1, pp. 46-91. Web.

Morgan, D. (2011). Washington. Web.

Sen, A. (1999). Democracy as a Universal Value . Journal of Democracy, Volume 10, Number 3, pp. 3-17. University press publishers. Web.

- Libya: Moammar Gaddafi

- Globalization and Democratization Effects on Libya

- International Intervention in Libya and Syria

- The U.S Government Drug Policy

- Egyptian Government Interference in Media

- Mine Resistant Ambush Protected Program

- Government: Formal and Informal Powers

- US President vs. the Canadian Prime Minister

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, June 2). Democratic Governance Concept. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democratic-governance-concept/

"Democratic Governance Concept." IvyPanda , 2 June 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/democratic-governance-concept/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Democratic Governance Concept'. 2 June.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Democratic Governance Concept." June 2, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democratic-governance-concept/.

1. IvyPanda . "Democratic Governance Concept." June 2, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democratic-governance-concept/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Democratic Governance Concept." June 2, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/democratic-governance-concept/.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Democratic Theory

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works and Bibliographies

- Classical Philosophy and Democracy

- Reference Works

- Early Modern Republicanism

- Enlightenment Liberalism

- Enlightenment Republicanism

- The Democratic Revolutions

- Post-Revolutionary Democratic Thought

- Contemporary Democratic Theory

- Empirical Democratic Theory

- Competitive Elitism

- Interest-Group Pluralism

- Contemporary Liberal Democracy

- Communitarianism

- Democracy and Capitalism

- Civil Society and Democracy

- Deliberative Democracy

- Radical Democracy

- Gender and Democracy

- Global Democracy

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Constitutionalism

- Democratic Citizenship

- Democratic Consolidation

- Democratization

- The Political Thought of the American Founders

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Cross-National Surveys of Public Opinion

- Politics of School Reform

- Ratification of the Constitution

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Democratic Theory by Michael Laurence LAST REVIEWED: 22 February 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 22 February 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756223-0162

Democratic theory is an established subfield of political theory that is primarily concerned with examining the definition and meaning of the concept of democracy, as well as the moral foundations, obligations, challenges, and overall desirability of democratic governance. Generally speaking, a commitment to democracy as an object of study and deliberation is what unites democratic theorists across a variety of academic disciplines and methodological orientations. When this commitment takes the form of a discussion of the moral foundations and desirability of democracy, normative theory results. When theorists concern themselves with the ways in which actual democracies function, their theories are empirical. Finally, when democratic theorists interrogate or formulate the meaning of the concept of democracy, their work is conceptual or semantic in orientation. Democratic theories typically operate at multiple levels of orientation. For example, definitions of democracy as well as normative arguments about when and why democracy is morally desirable are often rooted in empirical observations concerning the ways in which democracies have actually been known to function. In addition to a basic commitment to democracy as an object of study, most theorists agree that the concept democracy denotes some form or process of collective self-rule. The etymology of the word traces back to the Greek terms demos (the people, the many) and kratos (to rule). Yet beyond this basic meaning, a vast horizon of contestation opens up. Important questions arise: who constitutes the people and what obligations do individuals have in a democracy? What values are most important for a democracy and which ones make it desirable or undesirable as a form of government? How is democratic rule to be organized and exercised? What institutions should be used and how? Once instituted, does democracy require precise social, economic, or cultural conditions to survive in the long term? And why is it that democratic government is preferable to, say, aristocracy or oligarchy? These questions are not new. In fact, democratic theory traces its roots back to ancient Greece and the emergence of the first democratic governments in Western history. Ever since, philosophers, politicians, artists, and citizens have thought and written extensively about democracy. Yet democratic theory did not arise as an institutionalized academic or intellectual discipline until the 20th century. The works cited here privilege Anglo-American, western European, and, more generally, institutional variants of democratic theory, and, therefore, they do not exhaust the full range of thought on the subject.

A number of works have been published that provide overviews of the different historical and contemporary forms of democratic thought. Written by one of the most renowned democratic theorists in the United States, Dahl 2000 offers a brief and highly readable introduction to democratic thought that brings together normative and empirical strands of research. Crick 2002 offers another brief and accessible guide to the various traditions of democratic thought, while Cunningham 2002 presents a more comprehensive survey of the different currents of democratic theory and their historical developments. The text is notable for its discussion of theories of deliberative democracy and theories of radical pluralism, two of the more recent and popular trends in democratic theory. Held 2006 provides one of the most popular overviews of the various models of democracy coupled with a critical account of what democracy means in light of globalization. Another critical account of the field of contemporary democratic theory is offered by Shapiro 2003 , while Keane 2009 provides a historical narrative of sweeping scope that tells the story of democratic governments and ideals as they have developed and transformed since classical Greece. Dryzek and Dunleavy 2009 focuses on theories of the liberal democratic state, while Christiano 2008 provides an introductory exploration of normative democratic thought. Dunn 1992 offers a collection of essays written by leading political theorists that charts the development and contemporary significance of the idea of democracy.

Christiano, Tom. “ Democracy .” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2008.

An introductory survey of some of the major debates in the field of normative democratic theory. Emphasis is placed on the tasks of defining democracy, articulating the moral foundations of democracy, and explaining the requirements of democratic citizenship in large societies.

Crick, Bernard. Democracy: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

A brief guide to the history of the major traditions of democratic thought from ancient Greece to the present. Included are discussions of some of the major issues surrounding republicanism, populism, democratic citizenship, and the conditions required for the institution of a democracy.

Cunningham, Frank. Theories of Democracy: A Critical Introduction . London: Routledge, 2002.

Presents a summary of some of the major problems that confront democracies in the real world followed by a comprehensive discussion of historical and current paradigms of democratic thought.

Dahl, Robert. On Democracy . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.