173 Case Studies: Real Stories Of People Overcoming Struggles of Mental Health

At Tracking Happiness, we’re dedicated to helping others around the world overcome struggles of mental health.

In 2022, we published a survey of 5,521 respondents and found:

- 88% of our respondents experienced mental health issues in the past year.

- 25% of people don’t feel comfortable sharing their struggles with anyone, not even their closest friends.

In order to break the stigma that surrounds mental health struggles, we’re looking to share your stories.

Overcoming struggles

They say that everyone you meet is engaged in a great struggle. No matter how well someone manages to hide it, there’s always something to overcome, a struggle to deal with, an obstacle to climb.

And when someone is engaged in a struggle, that person is looking for others to join him. Because we, as human beings, don’t thrive when we feel alone in facing a struggle.

Let’s throw rocks together

Overcoming your struggles is like defeating an angry giant. You try to throw rocks at it, but how much damage is one little rock gonna do?

Tracking Happiness can become your partner in facing this giant. We are on a mission to share all your stories of overcoming mental health struggles. By doing so, we want to help inspire you to overcome the things that you’re struggling with, while also breaking the stigma of mental health.

Which explains the phrase: “Let’s throw rocks together”.

Let’s throw rocks together, and become better at overcoming our struggles collectively. If you’re interested in becoming a part of this and sharing your story, click this link!

Case studies

October 15, 2024

How I Stopped Obsessively Controlling My Body and Accepted My Values Instead

“I became interested in health and wellness and started to learn about healthy foods, nervous system exercises, energy, etc. And the same pattern of control started again disguised as health and wellness. Because of the way I was treated growing up and as a young adult, I felt there was something deeply wrong with me- like I was not loveable as I was. I needed to control my body to feel like I was enough, to make myself loveable so that I could be happy.”

Struggled with: Eating disorder Negative body image

Helped by: Self-acceptance Self-improvement

October 8, 2024

My Struggle with Depression While Finding Strength Through Mental Health Advocacy

“While I have a great support system, I did not feel like they truly understood what it felt like to be me. I really wished I could talk to people unfiltered about how sad I was and how I did not see a light at the end of the tunnel. I was still on my medicine and in therapy, but I had quit my fancy finance job, ended my relationship and urgently needed to work on myself.”

Struggled with: Depression

Helped by: Medication Self-Care

October 1, 2024

From Burnout to Balance: How I Found Happiness After Career Overload

“I experienced burnout. It was so severe that I could barely get out of bed or feed myself anything more than a bag of chips. I had also ground my teeth so badly that I was experiencing shooting pain in my jaw. When I saw the dentist, she told me that the damage to my teeth was permanent. To this day I often have pain when eating or drinking very hot or cold items.”

Struggled with: Burnout

Helped by: Self-Care Self-improvement

September 24, 2024

My Journey From Constant Self-Doubt and Anxiety to Becoming a Bestselling Author

“I’m honestly not sure if others knew or noticed because I kept it inside. People definitely noticed (and commented) that I was quiet or shy or didn’t speak up much – which didn’t help! But nobody knew what was really going on in my head and I didn’t talk about it, but I did write about it and writing has been my safe space ever since!”

Struggled with: Anxiety Self-doubt

Helped by: Self-improvement

September 17, 2024

My Fight Against Anxiety, PTSD, and Depression After Being Laid Off

“Neglect, abuse, and the profound impact of my mother’s involvement in the witness protection program marked my childhood. These experiences left deep emotional scars that have taken years to understand and manage. These challenges have ebbed and flowed over time. Yet, they’ve always been a constant presence, influencing how I see the world and interact with it.”

Struggled with: ADHD Anxiety Depression PTSD

Helped by: Reinventing yourself Self-improvement

September 10, 2024

My Journey of Overcoming Postpartum Depression and an Eating Disorder

“I was concerned about how my struggles might affect others’ perceptions of me and my competence as a mother and professional. This led me to mask my feelings and put on a brave face, even when I was feeling my lowest. Seeking help was a pivotal moment, but until then, I often felt like I had to navigate these challenges alone, despite the support and understanding that others might have been willing to offer.”

Struggled with: Eating disorder Postpartum depression

Helped by: Social support Therapy

September 3, 2024

Exercise, Therapy and Religion Helped Me Climb Out Of Alcoholism and Unhappiness

“The moment I felt something change for the better was when I was sitting at a bar sipping on a beer, and I called my father. I told him I truly didn’t want to drink anymore and really wanted to get sober. He sighed and said, “We tried to help you. Now it’s up to you just to stop drinking.” I asked him how that was going to be possible considering all of my options ran out. He screamed into the phone, “JUST STOP” and hung up.”

Struggled with: Addiction Assault

Helped by: Exercise God Therapy

August 27, 2024

A Bipolar Diagnosis Finally Helped Me understand How To Be Happy In Life

“After I was diagnosed, it took another 3 years before I found what balance of medication and therapy worked for me. I had to try to keep my grades up and maintain my friendships while battling severe mood swings and extreme tiredness, in addition to all of the regular drama that comes along with adolescence.”

Struggled with: Bipolar Disorder

Helped by: Medication Therapy

August 20, 2024

Overcoming Reactive Attachment Disorder and Depression with Self-Care and Therapy

“Despite experiencing severe depressive symptoms, including suicidal ideation, I made a concerted effort to appear upbeat and engaged in social settings. This involved forcing myself to smile, laugh, and participate in conversations as if everything was fine, even when I was internally battling intense emotional pain that I felt I was not safe to reveal.”

Struggled with: Childhood trauma Depression People-pleasing Reactive Attachment Disorder

Helped by: Self-Care Therapy

August 13, 2024

Finding Happiness At Sea As A Yacht Captain After Overcoming Depression and Anxiety

“If a situation is making you unhappy – a marriage, a job, a family member – anything – change the situation. You can leave, you can stop speaking to someone (yes, even a parent or another family member), and you can do so free of guilt because you are in charge of your own happiness, and life is too short to choose anything different for yourself.”

Struggled with: Anxiety Depression Suicidal

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Business How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Sep 07, 2023

Okay, let’s get real: case studies can be kinda snooze-worthy. But guess what? They don’t have to be!

In this article, I will cover every element that transforms a mere report into a compelling case study, from selecting the right metrics to using persuasive narrative techniques.

And if you’re feeling a little lost, don’t worry! There are cool tools like Venngage’s Case Study Creator to help you whip up something awesome, even if you’re short on time. Plus, the pre-designed case study templates are like instant polish because let’s be honest, everyone loves a shortcut.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study presentation?

What is the purpose of presenting a case study, how to structure a case study presentation, how long should a case study presentation be, 5 case study presentation examples with templates, 6 tips for delivering an effective case study presentation, 5 common mistakes to avoid in a case study presentation, how to present a case study faqs.

A case study presentation involves a comprehensive examination of a specific subject, which could range from an individual, group, location, event, organization or phenomenon.

They’re like puzzles you get to solve with the audience, all while making you think outside the box.

Unlike a basic report or whitepaper, the purpose of a case study presentation is to stimulate critical thinking among the viewers.

The primary objective of a case study is to provide an extensive and profound comprehension of the chosen topic. You don’t just throw numbers at your audience. You use examples and real-life cases to make you think and see things from different angles.

The primary purpose of presenting a case study is to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs, persuades and engages your audience.

Here’s the juicy part: presenting that case study can be your secret weapon. Whether you’re pitching a groundbreaking idea to a room full of suits or trying to impress your professor with your A-game, a well-crafted case study can be the magic dust that sprinkles brilliance over your words.

Think of it like digging into a puzzle you can’t quite crack . A case study lets you explore every piece, turn it over and see how it fits together. This close-up look helps you understand the whole picture, not just a blurry snapshot.

It’s also your chance to showcase how you analyze things, step by step, until you reach a conclusion. It’s all about being open and honest about how you got there.

Besides, presenting a case study gives you an opportunity to connect data and real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative. It helps to make your argument more relatable and accessible, increasing its impact on your audience.

One of the contexts where case studies can be very helpful is during the job interview. In some job interviews, you as candidates may be asked to present a case study as part of the selection process.

Having a case study presentation prepared allows the candidate to demonstrate their ability to understand complex issues, formulate strategies and communicate their ideas effectively.

The way you present a case study can make all the difference in how it’s received. A well-structured presentation not only holds the attention of your audience but also ensures that your key points are communicated clearly and effectively.

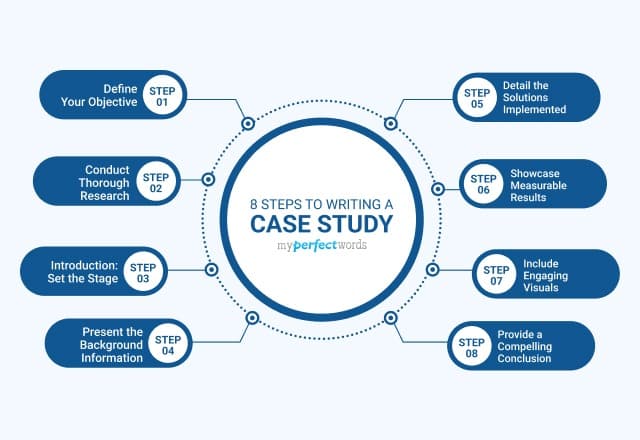

In this section, let’s go through the key steps that’ll help you structure your case study presentation for maximum impact.

Let’s get into it.

Open with an introductory overview

Start by introducing the subject of your case study and its relevance. Explain why this case study is important and who would benefit from the insights gained. This is your opportunity to grab your audience’s attention.

Explain the problem in question

Dive into the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. Provide enough background information for the audience to understand the issue. If possible, quantify the problem using data or metrics to show the magnitude or severity.

Detail the solutions to solve the problem

After outlining the problem, describe the steps taken to find a solution. This could include the methodology, any experiments or tests performed and the options that were considered. Make sure to elaborate on why the final solution was chosen over the others.

Key stakeholders Involved

Talk about the individuals, groups or organizations that were directly impacted by or involved in the problem and its solution.

Stakeholders may experience a range of outcomes—some may benefit, while others could face setbacks.

For example, in a business transformation case study, employees could face job relocations or changes in work culture, while shareholders might be looking at potential gains or losses.

Discuss the key results & outcomes

Discuss the results of implementing the solution. Use data and metrics to back up your statements. Did the solution meet its objectives? What impact did it have on the stakeholders? Be honest about any setbacks or areas for improvement as well.

Include visuals to support your analysis

Visual aids can be incredibly effective in helping your audience grasp complex issues. Utilize charts, graphs, images or video clips to supplement your points. Make sure to explain each visual and how it contributes to your overall argument.

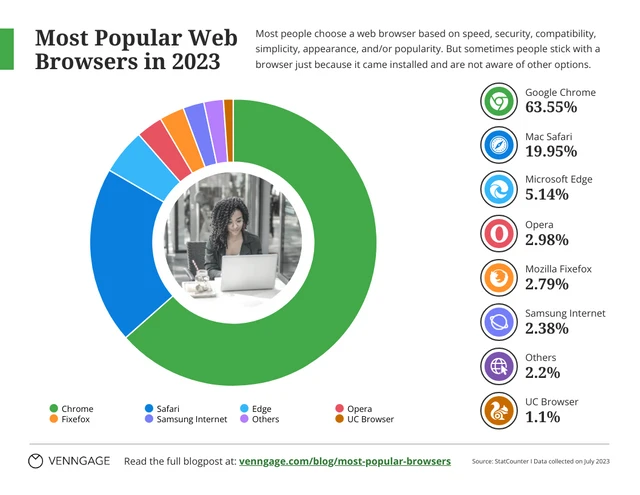

Pie charts illustrate the proportion of different components within a whole, useful for visualizing market share, budget allocation or user demographics.

This is particularly useful especially if you’re displaying survey results in your case study presentation.

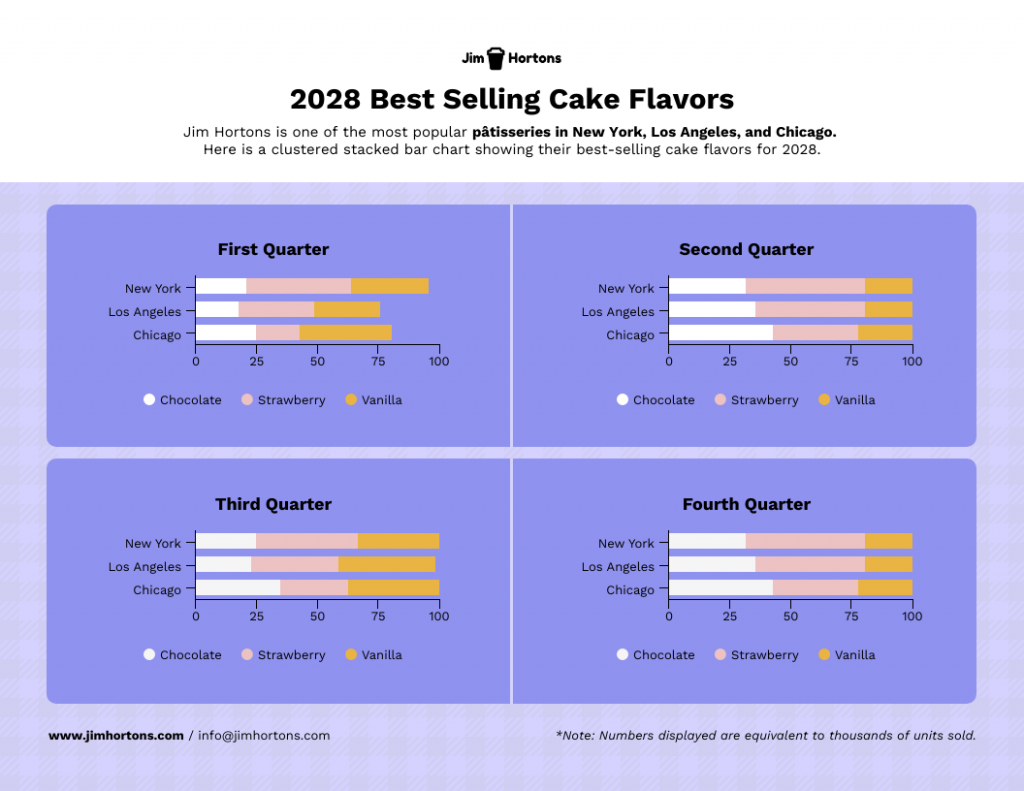

Stacked charts on the other hand are perfect for visualizing composition and trends. This is great for analyzing things like customer demographics, product breakdowns or budget allocation in your case study.

Consider this example of a stacked bar chart template. It provides a straightforward summary of the top-selling cake flavors across various locations, offering a quick and comprehensive view of the data.

Not the chart you’re looking for? Browse Venngage’s gallery of chart templates to find the perfect one that’ll captivate your audience and level up your data storytelling.

Recommendations and next steps

Wrap up by providing recommendations based on the case study findings. Outline the next steps that stakeholders should take to either expand on the success of the project or address any remaining challenges.

Acknowledgments and references

Thank the people who contributed to the case study and helped in the problem-solving process. Cite any external resources, reports or data sets that contributed to your analysis.

Feedback & Q&A session

Open the floor for questions and feedback from your audience. This allows for further discussion and can provide additional insights that may not have been considered previously.

Closing remarks

Conclude the presentation by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the takeaways. Thank your audience for their time and participation and express your willingness to engage in further discussions or collaborations on the subject.

Well, the length of a case study presentation can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the needs of your audience. However, a typical business or academic presentation often lasts between 15 to 30 minutes.

This time frame usually allows for a thorough explanation of the case while maintaining audience engagement. However, always consider leaving a few minutes at the end for a Q&A session to address any questions or clarify points made during the presentation.

When it comes to presenting a compelling case study, having a well-structured template can be a game-changer.

It helps you organize your thoughts, data and findings in a coherent and visually pleasing manner.

Not all case studies are created equal and different scenarios require distinct approaches for maximum impact.

To save you time and effort, I have curated a list of 5 versatile case study presentation templates, each designed for specific needs and audiences.

Here are some best case study presentation examples that showcase effective strategies for engaging your audience and conveying complex information clearly.

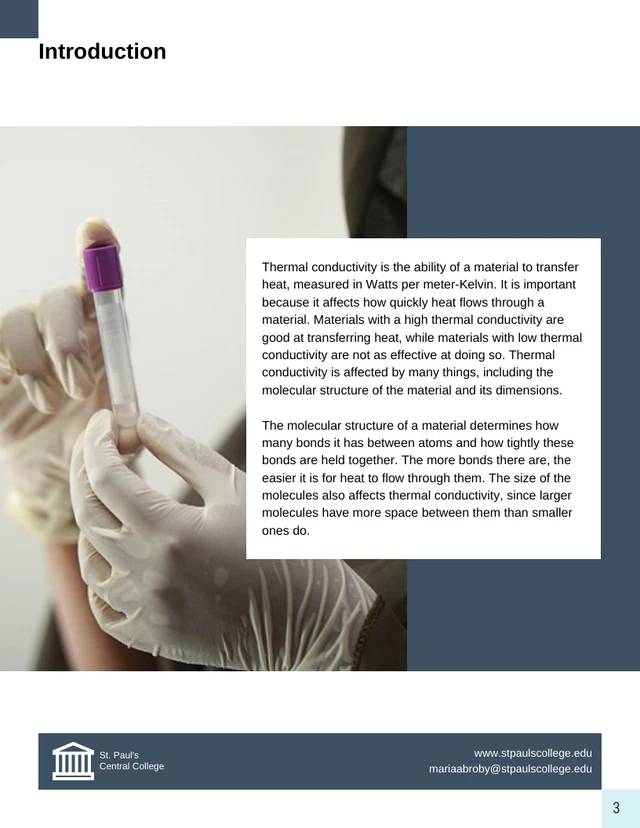

1 . Lab report case study template

Ever feel like your research gets lost in a world of endless numbers and jargon? Lab case studies are your way out!

Think of it as building a bridge between your cool experiment and everyone else. It’s more than just reporting results – it’s explaining the “why” and “how” in a way that grabs attention and makes sense.

This lap report template acts as a blueprint for your report, guiding you through each essential section (introduction, methods, results, etc.) in a logical order.

Want to present your research like a pro? Browse our research presentation template gallery for creative inspiration!

2. Product case study template

It’s time you ditch those boring slideshows and bullet points because I’ve got a better way to win over clients: product case study templates.

Instead of just listing features and benefits, you get to create a clear and concise story that shows potential clients exactly what your product can do for them. It’s like painting a picture they can easily visualize, helping them understand the value your product brings to the table.

Grab the template below, fill in the details, and watch as your product’s impact comes to life!

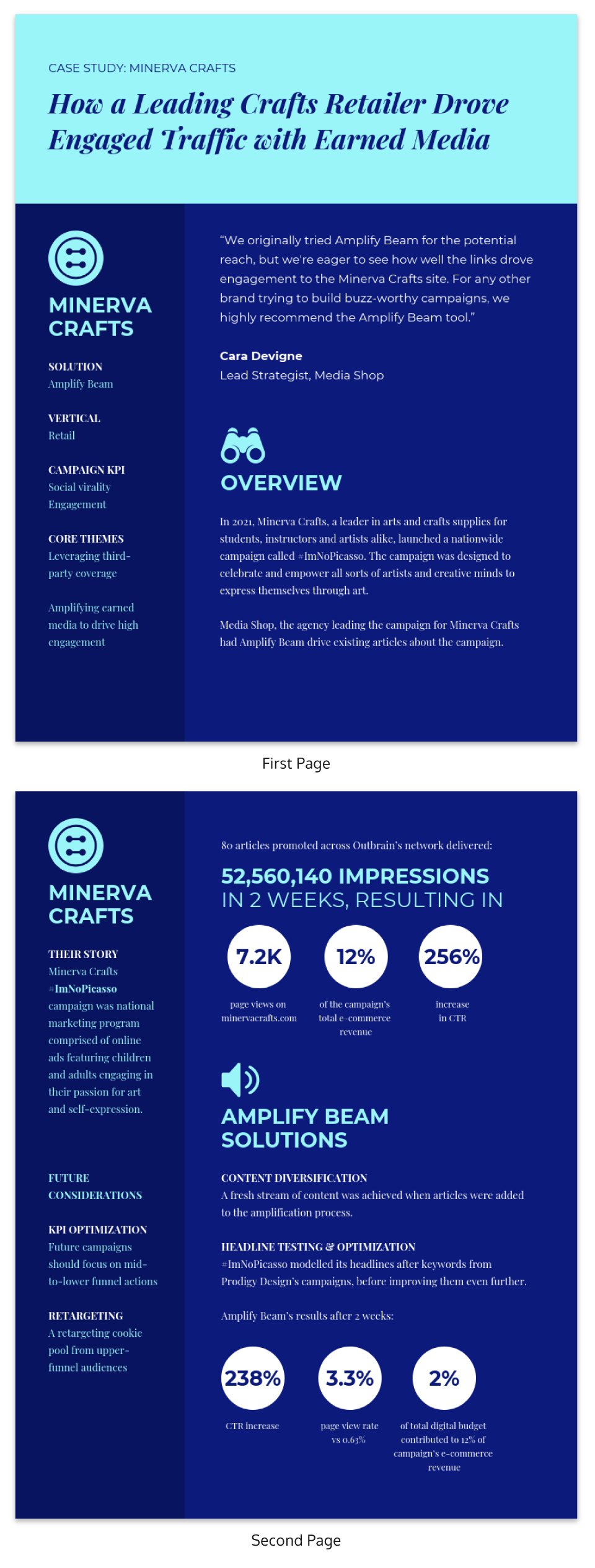

3. Content marketing case study template

In digital marketing, showcasing your accomplishments is as vital as achieving them.

A well-crafted case study not only acts as a testament to your successes but can also serve as an instructional tool for others.

With this coral content marketing case study template—a perfect blend of vibrant design and structured documentation, you can narrate your marketing triumphs effectively.

4. Case study psychology template

Understanding how people tick is one of psychology’s biggest quests and case studies are like magnifying glasses for the mind. They offer in-depth looks at real-life behaviors, emotions and thought processes, revealing fascinating insights into what makes us human.

Writing a top-notch case study, though, can be a challenge. It requires careful organization, clear presentation and meticulous attention to detail. That’s where a good case study psychology template comes in handy.

Think of it as a helpful guide, taking care of formatting and structure while you focus on the juicy content. No more wrestling with layouts or margins – just pour your research magic into crafting a compelling narrative.

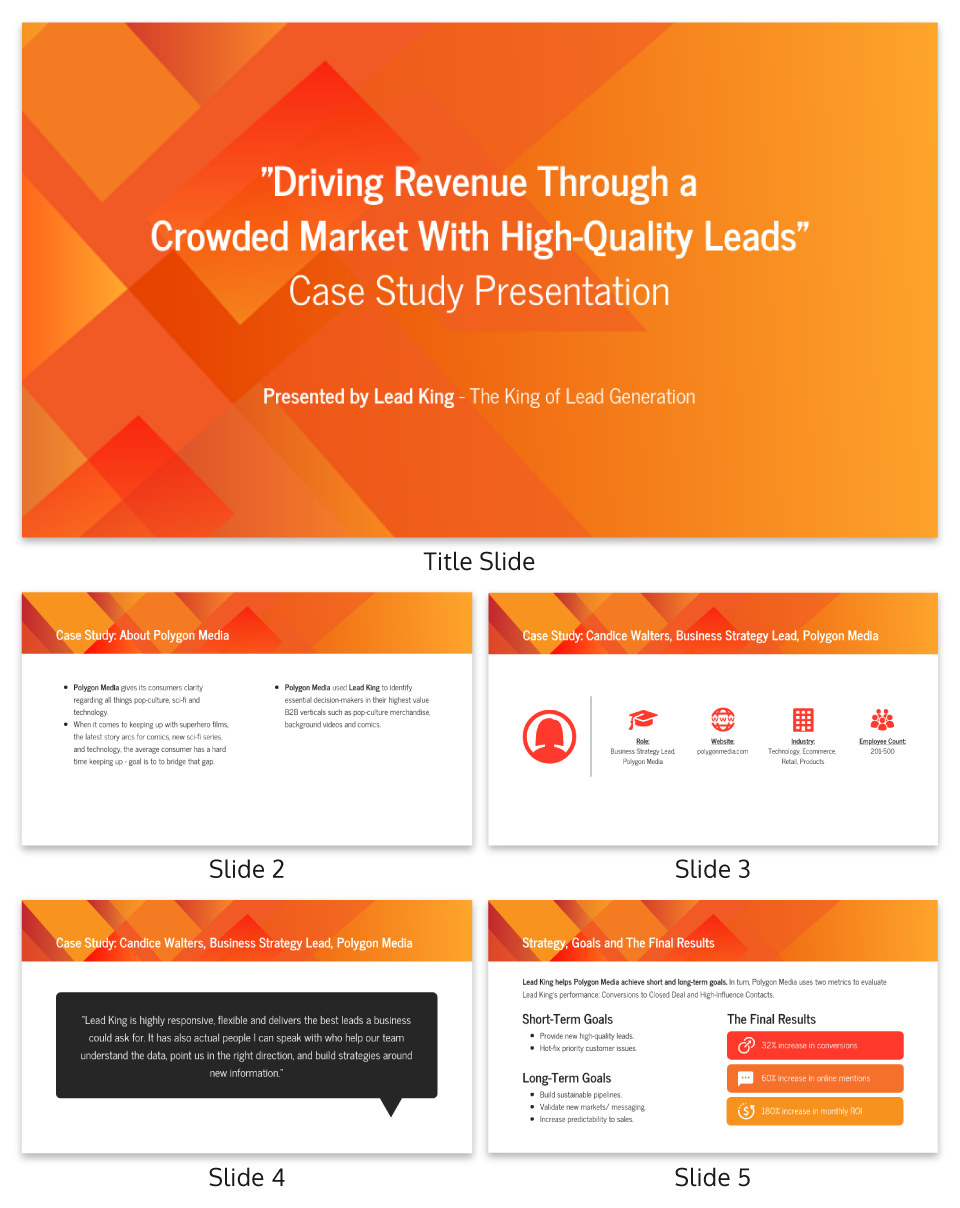

5. Lead generation case study template

Lead generation can be a real head-scratcher. But here’s a little help: a lead generation case study.

Think of it like a friendly handshake and a confident resume all rolled into one. It’s your chance to showcase your expertise, share real-world successes and offer valuable insights. Potential clients get to see your track record, understand your approach and decide if you’re the right fit.

No need to start from scratch, though. This lead generation case study template guides you step-by-step through crafting a clear, compelling narrative that highlights your wins and offers actionable tips for others. Fill in the gaps with your specific data and strategies, and voilà! You’ve got a powerful tool to attract new customers.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

So, you’ve spent hours crafting the perfect case study and are now tasked with presenting it. Crafting the case study is only half the battle; delivering it effectively is equally important.

Whether you’re facing a room of executives, academics or potential clients, how you present your findings can make a significant difference in how your work is received.

Forget boring reports and snooze-inducing presentations! Let’s make your case study sing. Here are some key pointers to turn information into an engaging and persuasive performance:

- Know your audience : Tailor your presentation to the knowledge level and interests of your audience. Remember to use language and examples that resonate with them.

- Rehearse : Rehearsing your case study presentation is the key to a smooth delivery and for ensuring that you stay within the allotted time. Practice helps you fine-tune your pacing, hone your speaking skills with good word pronunciations and become comfortable with the material, leading to a more confident, conversational and effective presentation.

- Start strong : Open with a compelling introduction that grabs your audience’s attention. You might want to use an interesting statistic, a provocative question or a brief story that sets the stage for your case study.

- Be clear and concise : Avoid jargon and overly complex sentences. Get to the point quickly and stay focused on your objectives.

- Use visual aids : Incorporate slides with graphics, charts or videos to supplement your verbal presentation. Make sure they are easy to read and understand.

- Tell a story : Use storytelling techniques to make the case study more engaging. A well-told narrative can help you make complex data more relatable and easier to digest.

Ditching the dry reports and slide decks? Venngage’s case study templates let you wow customers with your solutions and gain insights to improve your business plan. Pre-built templates, visual magic and customer captivation – all just a click away. Go tell your story and watch them say “wow!”

Nailed your case study, but want to make your presentation even stronger? Avoid these common mistakes to ensure your audience gets the most out of it:

Overloading with information

A case study is not an encyclopedia. Overloading your presentation with excessive data, text or jargon can make it cumbersome and difficult for the audience to digest the key points. Stick to what’s essential and impactful. Need help making your data clear and impactful? Our data presentation templates can help! Find clear and engaging visuals to showcase your findings.

Lack of structure

Jumping haphazardly between points or topics can confuse your audience. A well-structured presentation, with a logical flow from introduction to conclusion, is crucial for effective communication.

Ignoring the audience

Different audiences have different needs and levels of understanding. Failing to adapt your presentation to your audience can result in a disconnect and a less impactful presentation.

Poor visual elements

While content is king, poor design or lack of visual elements can make your case study dull or hard to follow. Make sure you use high-quality images, graphs and other visual aids to support your narrative.

Not focusing on results

A case study aims to showcase a problem and its solution, but what most people care about are the results. Failing to highlight or adequately explain the outcomes can make your presentation fall flat.

How to start a case study presentation?

Starting a case study presentation effectively involves a few key steps:

- Grab attention : Open with a hook—an intriguing statistic, a provocative question or a compelling visual—to engage your audience from the get-go.

- Set the stage : Briefly introduce the subject, context and relevance of the case study to give your audience an idea of what to expect.

- Outline objectives : Clearly state what the case study aims to achieve. Are you solving a problem, proving a point or showcasing a success?

- Agenda : Give a quick outline of the key sections or topics you’ll cover to help the audience follow along.

- Set expectations : Let your audience know what you want them to take away from the presentation, whether it’s knowledge, inspiration or a call to action.

How to present a case study on PowerPoint and on Google Slides?

Presenting a case study on PowerPoint and Google Slides involves a structured approach for clarity and impact using presentation slides :

- Title slide : Start with a title slide that includes the name of the case study, your name and any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Introduction : Follow with a slide that outlines the problem or situation your case study addresses. Include a hook to engage the audience.

- Objectives : Clearly state the goals of the case study in a dedicated slide.

- Findings : Use charts, graphs and bullet points to present your findings succinctly.

- Analysis : Discuss what the findings mean, drawing on supporting data or secondary research as necessary.

- Conclusion : Summarize key takeaways and results.

- Q&A : End with a slide inviting questions from the audience.

What’s the role of analysis in a case study presentation?

The role of analysis in a case study presentation is to interpret the data and findings, providing context and meaning to them.

It helps your audience understand the implications of the case study, connects the dots between the problem and the solution and may offer recommendations for future action.

Is it important to include real data and results in the presentation?

Yes, including real data and results in a case study presentation is crucial to show experience, credibility and impact. Authentic data lends weight to your findings and conclusions, enabling the audience to trust your analysis and take your recommendations more seriously

How do I conclude a case study presentation effectively?

To conclude a case study presentation effectively, summarize the key findings, insights and recommendations in a clear and concise manner.

End with a strong call-to-action or a thought-provoking question to leave a lasting impression on your audience.

What’s the best way to showcase data in a case study presentation ?

The best way to showcase data in a case study presentation is through visual aids like charts, graphs and infographics which make complex information easily digestible, engaging and creative.

Don’t just report results, visualize them! This template for example lets you transform your social media case study into a captivating infographic that sparks conversation.

Choose the type of visual that best represents the data you’re showing; for example, use bar charts for comparisons or pie charts for parts of a whole.

Ensure that the visuals are high-quality and clearly labeled, so the audience can quickly grasp the key points.

Keep the design consistent and simple, avoiding clutter or overly complex visuals that could distract from the message.

Choose a template that perfectly suits your case study where you can utilize different visual aids for maximum impact.

Need more inspiration on how to turn numbers into impact with the help of infographics? Our ready-to-use infographic templates take the guesswork out of creating visual impact for your case studies with just a few clicks.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

Congrats on mastering the art of compelling case study presentations! This guide has equipped you with all the essentials, from structure and nuances to avoiding common pitfalls. You’re ready to impress any audience, whether in the boardroom, the classroom or beyond.

And remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Venngage’s Case Study Creator is your trusty companion, ready to elevate your presentations from ordinary to extraordinary. So, let your confidence shine, leverage your newly acquired skills and prepare to deliver presentations that truly resonate.

Go forth and make a lasting impact!

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

Due to recent expansions in US sanctions against Russia and Belarus as well as existing country-level sanctions in Iran, North Korea, Syria, Cuba, and the Crimea region (each a “sanctioned country”), Zapier will no longer be able to provide services in any sanctioned country starting September 12, 2024. These sanctions prohibit US companies from offering certain IT and enterprise software services in a sanctioned region.

Starting September 12, 2024, Zapier customers will no longer be able to access Zapier services from a sanctioned country. We understand this may be inconvenient and appreciate your understanding as we navigate these regulatory requirements.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

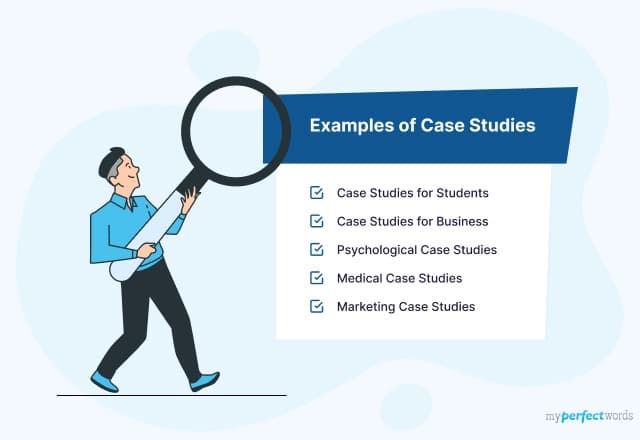

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to Write a Case Study: The Compelling Step-by-Step Guide

Is there a poignant pain point that needs to be addressed in your company or industry? Do you have a possible solution but want to test your theory? Why not turn this drive into a transformative learning experience and an opportunity to produce a high-quality business case study? However, before that occurs, you may wonder how to write a case study.

You may also be thinking about why you should produce one at all. Did you know that case studies are impactful and the fifth most used type of content in marketing , despite being more resource-intensive to produce?

Below, we’ll delve into what a case study is, its benefits, and how to approach business case study writing:

Definition of a Written case study and its Purpose

A case study is a research method that involves a detailed and comprehensive examination of a specific real-life situation. It’s often used in various fields, including business, education, economics, and sociology, to understand a complex issue better.

It typically includes an in-depth analysis of the subject and an examination of its context and background information, incorporating data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and existing literature.

The ultimate aim is to provide a rich and detailed account of a situation to identify patterns and relationships, generate new insights and understanding, illustrate theories, or test hypotheses.

Importance of Business Case Study Writing

As such an in-depth exploration into a subject with potentially far-reaching consequences, a case study has benefits to offer various stakeholders in the organisation leading it.

- Business Founders: Use business case study writing to highlight real-life examples of companies or individuals who have benefited from their products or services, providing potential customers with a tangible demonstration of the value their business can bring. It can be effective for attracting new clients or investors by showcasing thought leadership and building trust and credibility.

- Marketers through case studies and encourage them to take action: Marketers use a case studies writer to showcase the success of a particular product, service, or marketing campaign. They can use persuasive storytelling to engage the reader, whether it’s consumers, clients, or potential partners.

- Researchers: They allow researchers to gain insight into real-world scenarios, explore a variety of perspectives, and develop a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to success or failure. Additionally, case studies provide practical business recommendations and help build a body of knowledge in a particular field.

How to Write a Case Study – The Key Elements

Considering how to write a case study can seem overwhelming at first. However, looking at it in terms of its constituent parts will help you to get started, focus on the key issue(s), and execute it efficiently and effectively.

Problem or Challenge Statement

A problem statement concisely describes a specific issue or problem that a written case study aims to address. It sets the stage for the rest of the case study and provides context for the reader.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study problem statement:

- Identify the problem or issue that the case study will focus on.

- Research the problem to better understand its context, causes, and effects.

- Define the problem clearly and concisely. Be specific and avoid generalisations.

- State the significance of the problem: Explain why the issue is worth solving. Consider the impact it has on the individual, organisation, or industry.

- Provide background information that will help the reader understand the context of the problem.

- Keep it concise: A problem statement should be brief and to the point. Avoid going into too much detail – leave this for the body of the case study!

Here is an example of a problem statement for a case study:

“ The XYZ Company is facing a problem with declining sales and increasing customer complaints. Despite improving the customer experience, the company has yet to reverse the trend . This case study will examine the causes of the problem and propose solutions to improve sales and customer satisfaction. “

Solutions and interventions

Business case study writing provides a solution or intervention that identifies the best course of action to address the problem or issue described in the problem statement.

Here are some steps to help you write a case study solution or intervention:

- Identify the objective , which should be directly related to the problem statement.

- Analyse the data, which could include data from interviews, observations, and existing literature.

- Evaluate alternatives that have been proposed or implemented in similar situations, considering their strengths, weaknesses, and impact.

- Choose the best solution based on the objective and data analysis. Remember to consider factors such as feasibility, cost, and potential impact.

- Justify the solution by explaining how it addresses the problem and why it’s the best solution with supportive evidence.

- Provide a detailed, step-by-step plan of action that considers the resources required, timeline, and expected outcomes.

Example of a solution or intervention for a case study:

“ To address the problem of declining sales and increasing customer complaints at the XYZ Company, we propose a comprehensive customer experience improvement program. “

“ This program will involve the following steps:

- Conducting customer surveys to gather feedback and identify areas for improvement

- Implementing training programs for employees to improve customer service skills

- Revising the company’s product offerings to meet customer needs better

- Implementing a customer loyalty program to encourage repeat business “

“ These steps will improve customer satisfaction and increase sales. We expect a 10% increase in sales within the first year of implementation, based on similar programs implemented by other companies in the industry. “

Possible Results and outcomes

Writing case study results and outcomes involves presenting the impact of the proposed solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study results and outcomes:

- Evaluate the solution by measuring its effectiveness in addressing the problem statement. That could involve collecting data, conducting surveys, or monitoring key performance indicators.

- Present the results clearly and concisely, using graphs, charts, and tables to represent the data where applicable visually. Be sure to include both quantitative and qualitative results.

- Compare the results to the expectations set in the solution or intervention section. Explain any discrepancies and why they occurred.

- Discuss the outcomes and impact of the solution, considering the benefits and drawbacks and what lessons can be learned.

- Provide recommendations for future action based on the results. For example, what changes should be made to improve the solution, or what additional steps should be taken?

Example of results and outcomes for a case study:

“ The customer experience improvement program implemented at the XYZ Company was successful. We found significant improvement in employee health and productivity. The program, which included on-site exercise classes and healthy food options, led to a 25% decrease in employee absenteeism and a 15% increase in productivity . “

“ Employee satisfaction with the program was high, with 90% reporting an improved work-life balance. Despite initial costs, the program proved to be cost-effective in the long run, with decreased healthcare costs and increased employee retention. The company plans to continue the program and explore expanding it to other offices .”

Case Study Key takeaways

Key takeaways are the most important and relevant insights and lessons that can be drawn from a case study. Key takeaways can help readers understand the most significant outcomes and impacts of the solution or intervention.

Here are some steps to help you write case study key takeaways:

- Summarise the problem that was addressed and the solution that was proposed.

- Highlight the most significant results from the case study.

- Identify the key insights and lessons , including what makes the case study unique and relevant to others.

- Consider the broader implications of the outcomes for the industry or field.

- Present the key takeaways clearly and concisely , using bullet points or a list format to make the information easy to understand.

Example of key takeaways for a case study:

- The customer experience improvement program at XYZ Company successfully increased customer satisfaction and sales.

- Employee training and product development were critical components of the program’s success.

- The program resulted in a 20% increase in repeat business, demonstrating the value of a customer loyalty program.

- Despite some initial challenges, the program proved cost-effective in the long run.

- The case study results demonstrate the importance of investing in customer experience to improve business outcomes.

Steps for a Case Study Writer to Follow

If you still feel lost, the good news is as a case studies writer; there is a blueprint you can follow to complete your work. It may be helpful at first to proceed step-by-step and let your research and analysis guide the process:

- Select a suitable case study subject: Ask yourself what the purpose of the business case study is. Is it to illustrate a specific problem and solution, showcase a success story, or demonstrate best practices in a particular field? Based on this, you can select a suitable subject by researching and evaluating various options.

- Research and gather information: We have already covered this in detail above. However, always ensure all data is relevant, valid, and comes from credible sources. Research is the crux of your written case study, and you can’t compromise on its quality.

- Develop a clear and concise problem statement: Follow the guide above, and don’t rush to finalise it. It will set the tone and lay the foundation for the entire study.

- Detail the solution or intervention: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed solution or intervention.

- Present the results and outcomes: Remember that a case study is an unbiased test of how effectively a particular solution addresses an issue. Not all case studies are meant to end in a resounding success. You can often learn more from a loss than a win.

- Include key takeaways and conclusions: Follow the steps above to detail your proposed business case study solution or intervention.

Tips for How to Write a Case Study

Here are some bonus tips for how to write a case study. These tips will help improve the quality of your work and the impact it will have on readers:

- Use a storytelling format: Just because a case study is research-based doesn’t mean it has to be boring and detached. Telling a story will engage readers and help them better identify with the problem statement and see the value in the outcomes. Framing it as a narrative in a real-world context will make it more relatable and memorable.

- Include quotes and testimonials from stakeholders: This will add credibility and depth to your written case study. It also helps improve engagement and will give your written work an emotional impact.

- Use visuals and graphics to support your narrative: Humans are better at processing visually presented data than endless walls of black-on-white text. Visual aids will make it easier to grasp key concepts and make your case study more engaging and enjoyable. It breaks up the text and allows readers to identify key findings and highlights quickly.

- Edit and revise your case study for clarity and impact: As a long and involved project, it can be easy to lose your narrative while in the midst of it. Multiple rounds of editing are vital to ensure your narrative holds, that your message gets across, and that your spelling and grammar are correct, of course!

Our Final Thoughts

A written case study can be a powerful tool in your writing arsenal. It’s a great way to showcase your knowledge in a particular business vertical, industry, or situation. Not only is it an effective way to build authority and engage an audience, but also to explore an important problem and the possible solutions to it. It’s a win-win, even if the proposed solution doesn’t have the outcome you expect. So now that you know more about how to write a case study, try it or talk to us for further guidance.

Are you ready to write your own case study?

Begin by bookmarking this article, so you can come back to it. And for more writing advice and support, read our resource guides and blog content . If you are unsure, please reach out with questions, and we will provide the answers or assistance you need.

Categorised in: Resources

This post was written by Premier Prose

© 2024 Copyright Premier Prose. Website Designed by Ubie

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

More information about our Cookie Policy

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).

Encourage faculty teams that teach common courses to build appropriate instructional materials, grading rubrics, videos, sample cases, and teaching notes.

When selecting case studies, we have found that the best ones for PACADI analyses are about 15 pages long and revolve around a focal management decision. This length provides adequate depth yet is not protracted. Some of our tested and favorite marketing cases include Brand W , Hubspot , Kraft Foods Canada , TRSB(A) , and Whiskey & Cheddar .

Art Weinstein , Ph.D., is a professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He has published more than 80 scholarly articles and papers and eight books on customer-focused marketing strategy. His latest book is Superior Customer Value—Finding and Keeping Customers in the Now Economy . Dr. Weinstein has consulted for many leading technology and service companies.

Herbert V. Brotspies , D.B.A., is an adjunct professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University. He has over 30 years’ experience as a vice president in marketing, strategic planning, and acquisitions for Fortune 50 consumer products companies working in the United States and internationally. His research interests include return on marketing investment, consumer behavior, business-to-business strategy, and strategic planning.

John T. Gironda , Ph.D., is an assistant professor of marketing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research has been published in Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing , and Journal of Marketing Management . He has also presented at major marketing conferences including the American Marketing Association, Academy of Marketing Science, and Society for Marketing Advances.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

How to Write a Case Study Analysis

Before writing a case study analysis, it is important to identify a relevant subject and research problem. While preparing to write, the author should critically assess the potential problem and the need for in-depth analysis. For example, hidden problems, outdated information, or a feasible recommendation are all indications that a problem lends itself to a case study. The introduction should not only include a problem statement but should also note its importance, provide background information, supply a rationale for applying a case study method, and suggest potential advancement of knowledge in the given field.

Literature Review

The key purpose of the literature review in a case study analysis is to present the historical context of a problem and its background based on academic evidence. Synthesis of existing studies contributes to the subsequent substantial aspects that should be taken into account:

- Identify the context of the problem under consideration and locate related studies, showing the link between them. Each of the academic pieces used to write a case study should make a particular contribution to understanding or resolving the target problem.

- Connect all the studies together and provide a critical appraisal. One of the most common mistakes is to merely present existing evidence without any analysis or clarification of how one or another research investigation relates to the problem.

- Discover and discuss any gaps in the literature, demonstrating how the case study adds more value and credibility to the available evidence. For example, if the case study focuses on strategies used to promote feminism, it is possible to explore the gap of how this movement is developing in the Middle East, where it is not as evident as in Western countries.

- Identify conflicts and contradictory issues that can be found in the literature. This helps in coming closer to the resolution of the problem. If, for example, two different approaches are regarded as mutually exclusive in one study, and the same approaches are considered compatible in another, it is an evident conflict. A discussion of such contradictory issues should be placed in the case study to suggest feasible solutions.

- Locate the case study in the context of the literature and within the larger scale. More to the point, by synthesizing the pertinent literature and indicating the role of the case study, the researcher shows that he or she has made essential efforts toward addressing the problem.

In this section, it is important to clarify why a specific subject and problem were chosen for study. A range of subjects is possible, and the type chosen will impact how the method will be described. The key types of subjects include phenomena, places, persons, and events.

- The investigation of a phenomenon as a target of a case study implies that certain facts or circumstances exist and require change and improvement. The behavioral and social sciences often require the study of challenging issues such as the causes of high employee turnover or a low level of motivation on the part of managers. In such a case, cause-and-effect relationships should be established to evaluate the environment.

- If an accident or event composes the basis of the case study, its time and place will set the specifics of the research. A rare or critical event as well as any one of a number of common situations may be selected; in any case, a rationale should be provided to support the choice. As a rule, rare events require forging a new way of thinking regarding the occurrence, while dealing with a commonly encountered situation is associated with challenging existing hypotheses. In both types of cases, the following elements should be included in the case analysis: timeframe, circumstances, and consequences.

- A focus on a person as the subject of a study refers to scrutinizing the individual’s experience, relationships, and behaviors. For example, a discussion of Mark Zuckerberg as the creator of Facebook requires identifying the background, conflicts, and positive and negative consequences of his contributions to society.

- A place as the subject of a case study should be special, and it should be clear to readers why a particular area or neighborhood was chosen. What is, for example, the aim of focusing on China and Japan instead of the United States when exploring homelessness issues?

An important part of case study research or development in the field of the social and behavioral sciences involves discussing and interpreting findings. Therefore, after a thorough literature review, it is necessary to compare, reiterate, and revise the findings based on the experiences reported in previous studies along with the writer’s personal understanding of the subject studied.

- The discussion section may start with a brief summary of the findings that are of the greatest importance and particularly thought-provoking.

- The results should be assessed in terms of the hypothesis and objectives of the research. Briefly reiterating these, indicate whether the data obtained have confirmed the hypothesis, the goal has been achieved, and the research tasks have been addressed.