The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Order vs. Liberty: The Alien and Sedition Acts

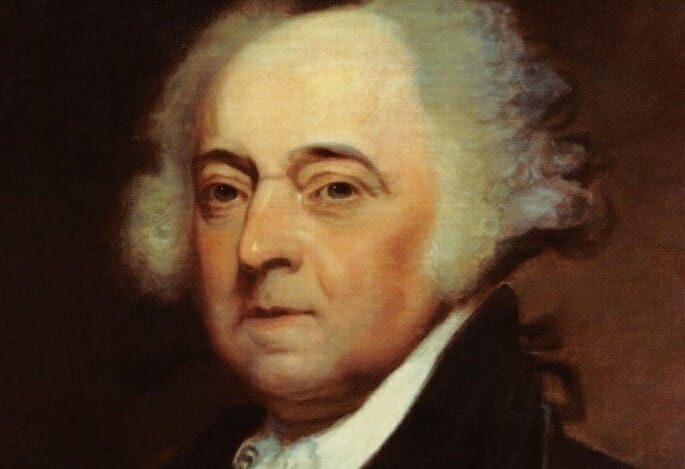

O n July 4, 1798, the citizens of the capital city of Philadelphia turned out in large numbers to celebrate the nation’s independence day. While militia companies marched through the streets, church bells rang, and artillery units fired salutes, members of the United States Senate were trying to conduct a debate on a critical bill. One senator noted “the military parade so attracted the attention of the majority that much the greater part of them stood with their bodies out of the windows and could not be kept to order.” Once they resumed their deliberations, however, the Federalist majority succeeded in gaining passage of an implausible bill, one quickly approved by the House of Representatives and signed on July 14 by President John Adams.

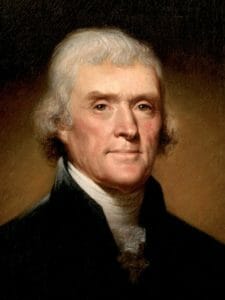

Ironically, as senators celebrated the freedom they had won from Britain, they approved a sedition bill that made it illegal to publish or utter any statements about the government that were “false, scandalous and malicious” with the “intent to defame” or to bring Congress or the president into “contempt or disrepute.” This bill, seemingly a violation of the Constitution’s First Amendment free speech protections, had a chilling effect on members of the Republican Party and its leader, Thomas Jefferson, who admitted that he feared “to write what I think.”

Support for this restrictive legislation had grown out of Federalist belief that the young nation was facing its gravest crisis yet, in the possibility of war with France and the spread of anti-immigrant feeling. The new law violated the beliefs of many Republicans, who regarded Federalists as reactionary defenders of privilege intent on bringing back the monarchy. Federalists saw their Republican opposites as irresponsible radicals eager to incite a social revolution as democratic as the one that had torn through France.

Recommended for you

This British Officer Developed a Revolutionary Rifle Whose Worth He Was Never Able to Prove in Battle

Abigail Adams Persevered Through Siege and Smallpox to Support the Revolution

Revolutionary War Soldiers Slated for Reburial 243 Years After Battle

Nothing divided Federalist from Republican more than their response to the French Revolution. Republicans applauded the revolutionaries’ destruction of aristocratic privileges, the overthrow of the monarchy, and the implementation of constitutional government. Yet, Federalists saw the same dramatic changes as the degeneration of legitimate government into mob rule, particularly during the bloody “Reign of Terror” when “counterrevolutionaries” lost their lives on the guillotine.

Federalist fears deepened as they watched the new French republican government encourage wars of liberation and conquest in Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, and the Italian peninsula. Rumors were rampant in 1798 about a possible French invasion of America, one that allegedly would be supported by American traitors and a population of French émigrés that had grown to more than 20,000.

The nation’s rapidly growing immigrant population deeply troubled Federalists. One Pennsylvania newspaper argued that “none but the most vile and worthless” were inundating the country. William Shaw, the president’s nephew, arguing that “all our present difficulties may be traced” to the “hordes of Foreigners” in the land, contended America should “no longer” be “an asylum to all nations.” Federalists worried about the 60,000 Irish immigrants in the new nation, some of whom had been exiled for plotting against British rule. These malcontents, they argued, along with French immigrants, and a sprinkling of British radicals like the liberal theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley, presented a grave challenge to the nation. The Federalists feared that the extremist ideas of the dissenters would corrupt and mobilize the destitute.

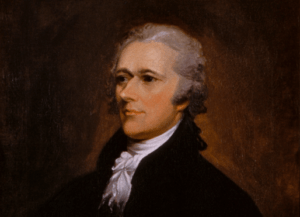

The British government, even more terrified than the Americans that ideas from the radical French regime might spread, had been at war with France for five years, trying to contain it. Both nations had seized neutral American ships headed to their enemy’s ports. President Adams initiated a two-pronged plan to stop the French from seizing any further ships. He sent three emissaries to negotiate with the French government, and he worked to push bills through Congress to increase the size of the navy and army. Federalist revulsion at anything associated with France reached a peak in spring 1798 when word arrived in Philadelphia that three French agents, identified only as X, Y, and Z, had demanded a bribe from the American diplomats before they would begin negotiations.

Insulted by the French government, convinced that war was inevitable, and anxious over a “dangerous” alien population in their midst, Federalists in Philadelphia were ready to believe any rumor. They saw no reason to doubt the warning in a letter found outside the president’s residence in late April. It supposedly contained information about a plot by a group of Frenchmen “to sit [sic] fire to the City in various parts, and to Massacre the inhabitants.” Hundreds of militiamen patrolled the city streets as a precaution, and a special guard was assigned to the president’s home. John Adams ordered “chests of arms from the war-office,” as he was “determined to defend my house at the expense of my life.”

In such a crisis atmosphere, Federalists took action to prevent domestic subversion. They supported four laws passed in June and July 1798 to control the threats they believed foreigners posed to the security of the nation and to punish the opposition party for its seditious libel.

Two of these laws represented the Federalist effort to address perceived threats from the nation’s immigrant groups. The Alien Enemies Act permitted the deportation of aliens who hailed from a nation with which the United States was at war, while the Alien Friends Act empowered the president, during peacetime, to deport any alien whom he considered dangerous.

Although some historians acknowledge that there were legitimate national security concerns involved in the passage of the two alien acts, others conclude that the two additional pieces of legislation were blatant efforts to destroy the Republican Party, which had gained many immigrant supporters.

The Naturalization Act extended the residency requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years. For a few politicians, such as Congressmen Robert Goodloe Harper and Harrison Gray Otis, even this act was insufficient. They believed that citizenship should be limited to those born in the United States.

Apart from its limitations on speech, the Sedition Act, the last of the four laws, made it illegal to “unlawfully combine or conspire together, with intent to oppose any measure or measures of the government.” While the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution established that Congress couldn’t pass laws “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,” there had been little discussion about the amendment’s precise meaning since its adoption seven years earlier.

In 1798 many Federalists drew upon Commentaries on the Laws of England written by Sir William Blackstone–the man considered by the framers of the Constitution to be the oracle of the common law–for their definition of liberty of the press. Blackstone wrote, “liberty of the press . . . consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications.” However, if a person “publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his own temerity.” In other words, if a person spoke or wrote remarks that could be construed as seditious libel, they weren’t entitled to free speech protection.

According to the Federalists, if seditious libel meant any effort to malign or weaken the government, then the Republican press was repeatedly guilty. Republican papers, claimed the Federalists, such as the Philadelphia Aurora, the New York Argus, the Richmond Examiner, and Boston’s Independent Chronicle printed the most scurrilous statements, lies, and misrepresentations about President Adams and the Federalist Party.

The president’s wife, Abigail, complained bitterly about journalistic “abuse, deception and falsehood.” Particularly galling to her were the characterizations of her husband in editor Benjamin Bache’s Aurora. In April 1798 Bache called the president “old, querulous, Bald, blind, crippled, Toothless Adams.” Bache, she argued, was a “lying wretch” given to the “most insolent and abusive” language. He wrote with the “malice” of Satan. The First Lady repeatedly demanded that something be done to stop this “wicked and base, violent and calumniating abuse” being “leveled against the Government.” She argued that if journalists like Bache weren’t stopped, the nation would be plunged into a “civil war.”

At the same time, Federalists were hardly models of decorum when describing Republicans. Their opponents were, one Federalist wrote, “democrats, mobocrats and all other kinds of rats.” Federalist Noah Webster characterized Republicans as “the refuse, the sweepings of the most depraved part of mankind from the most corrupt nations on earth.”

Although President Adams neither framed the Sedition Act nor encouraged its introduction, he certainly supported it. He issued many public statements about the evils of the opposition press. Adams believed that journalists who deliberately distorted the news to mislead the people could cause great harm to a representative democracy.

Letters and remarks of John and Abigail Adams made passage of a sedition bill easier, but the task of pushing it through Congress fell to Senator James Lloyd of Maryland and Congressmen Robert Goodloe Harper and Harrison Gray Otis. Although it passed by a wide margin in the Senate, the bill barely gained approval in the House of Representatives, where the vote was 44 to 41. To win even that small majority, Harper and Otis had to change the original bill in significant ways. Prosecutors would have to prove malicious intent, and truth would be permitted as a defense. Juries, not judges, would determine whether a statement was libelous. To underscore its political purpose, the act was to expire on March 3, 1801, the last day of President Adams’ term of office.

Prosecutions began quickly. On June 26, even before the Sedition Act was passed, Supreme Court Justice Richard Peters issued a warrant for the arrest of Benjamin Bache. Bache, the most powerful of all the Republican newspaper editors, was charged with “libeling the President and the Executive Government in a manner tending to excite sedition and opposition to the laws.” Less than two weeks later, federal marshals arrested John Daly Burk, editor of the New York newspaper Time Piece, for making “seditious and libelous” statements against the president. Neither faced trial, however. Bache died in Philadelphia during the yellow fever epidemic of September 1798, and Burk, who wasn’t a citizen, agreed to deportation if charges were dropped. He then fled to Virginia to live under an assumed name.

During the next two years 17 people were indicted under the Sedition Act, and 10 were convicted. Most were journalists. Included among them were William Duane, who had succeeded Benjamin Bache as editor of the Aurora; Thomas Cooper, a British radical who edited a small Pennsylvania newspaper; Charles Holt, editor of a New London, Connecticut, newspaper; and James Callender, who had worked on the Aurora before moving to Virginia’s Richmond Examiner. Like Benjamin Bache, Callender delighted in condemning the president.

The Federalists didn’t target only journalists. They went after other individuals, including David Brown of Dedham, Massachusetts, who spouted anti-government rhetoric wherever a crowd gathered. Brown was arrested in April 1799, charged with “uttering seditious pieces” and helping to erect a liberty pole with a placard that read “A Speedy Retirement to the President. No Sedition bill, No Alien bill, Downfall to the Tyrants of America.”

Incredibly, even an inebriated Republican, Luther Baldwin of Newark, New Jersey, became a victim. Following the adjournment of Congress in July 1798, President Adams and his wife were traveling through Newark on their way to their home in Quincy, Massachusetts. Residents lined the streets as church bells rang, and ceremonial cannon fire greeted the party. As the procession made its way past a local tavern owned by John Burnet, one of the patrons remarked, “There goes the President and they are firing at his a__.” According to the Newark Centinel of Freedom, Baldwin added that, “he did not care if they fired thro’ his a__.” Burnet overheard the exchange and exclaimed, “That is seditious.” Baldwin was arrested and later convicted of speaking “seditious words tending to defame the President and Government of the United States.” He was fined $150, assessed court costs and expenses, and sent to jail until he paid the fine and fees.

The most outrageous case, however, involved Congressman Matthew Lyon, a Republican from Vermont. This fiery Irishman was one of the sharpest critics of President Adams and the Federalists. He had even engaged in a brawl on the House floor with Federalist Roger Griswold. Convinced that the Federalists intended to use the Sedition Act to silence their congressional opposition, Lyon confided to a colleague that it “most probably would be brought to bear upon himself first victim of all.”

While not the initial victim, Lyon quickly felt the wrath of the majority party. In the summer of 1798, he wrote an article criticizing President Adams’ “continual grasp for power” and his “unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice.” During his fall re-election campaign, Lyon also quoted from a letter that suggested Congress should dispatch the president to a “mad house” for his handling of the French crisis. In October, a federal grand jury indicted Lyon for stirring up sedition and bringing “the President and government of the United States into contempt.”

United States Supreme Court justices, sitting as circuit court judges, presided in the sedition trials. These judges, all Federalists, rejected the efforts of defendants and their counsel to challenge the law’s constitutionality. Samuel Chase, who sat in three of the cases, clearly was on a mission. “There is nothing we should more dread,” he argued, “than the licentiousness of the press.”

Chase and the other judges handed down tough sentences. While none imposed the statute’s maximum penalties of a $2,000 fine or a jail sentence of two years, they often sent the guilty to jail. Most of the convicted endured three- or four-month sentences. James Callender, however, served nine months, and David Brown twice as long. The average fines were about $300, although Luther Baldwin’s fine was $150 and Matthew Lyon’s was $1,000.

As the trials progressed, two Republican Party leaders, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, tried to overturn the Sedition Act. Concluding that the Bill of Rights couldn’t prevent abuses of power by the federal government, the two men collaborated on a set of protest resolutions asserting that the government was a compact created by the states and that citizens, speaking through their state legislatures, had the right to judge the constitutionality of actions taken by the government. In this instance, they called upon the states to join them in declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts to be “void, and of no force.”

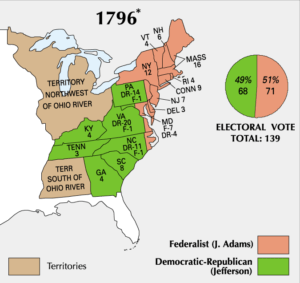

While only Kentucky and Virginia endorsed the resolutions, the efforts of Jefferson and Madison encouraged Republicans to make the Alien and Sedition Acts major issues in the campaign of 1800. Voter anger over these bills, along with higher taxes and the escalating federal debt resulting from increased defense spending, gave Republicans a majority in the House of Representatives. The Federalists lost almost 40 seats, leaving the new Congress with 66 Republicans and only 40 Federalists.

There were other unexpected results from the passage of the Sedition Act. Clearly, Federalists had hoped to stifle the influence of the fewer than 20 Republican newspapers published in 1798. Some, like John Daly Burk’s Time Piece, did cease publication; others suspended operation while their editors were in jail. However, circulation increased for the majority of the periodicals. Most discouraging to the Federalists, particularly as the campaigns for the 1800 election got under way, was the fact that more than 30 new Republican newspapers began operation following passage of the Sedition Act.

Not even prison stopped Republican Congressman Matthew Lyon. The most visible target of the Federalists, Lyon conducted his re-election campaign from his jail cell in Vergennes, Vermont. Considered a martyr by his supporters, Lyon regularly contributed to this image through letters and newspaper articles. “It is quite a new kind of jargon to call a Representative of the People an Opposer of the Government because he does not, as a legislator, advocate and acquiesce in every proposition that comes from the Executive,” he wrote. In a December run-off election, Lyon won easily.

By 1802, in the wake of the Federalist election defeat, the Alien Friends Act, the Sedition Act, and the Naturalization Act had expired or been repealed. The Alien Enemies Act remained in effect, but no one had been prosecuted under its provisions because the United States hadn’t declared war on France, a necessary condition for the law’s implementation. After winning the presidency in the 1800 election, Thomas Jefferson pardoned all those convicted of violating the Sedition Act who remained in prison.

By virtually every measure, the Federalist effort to impose a one-party press and a one-party government on the fledgling nation had failed. Ironically, the Sedition Act prompted the opposition to expand its view of free speech and freedom of the press. In a series of essays, tracts, and books, Republicans began to argue that the First Amendment protected citizens from any federal restraint on the press or speech. Notable among them was a pamphlet entitled An Essay on the Liberty of the Press, published in 1799 by George Hay, a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. Hay argued “that if the words freedom of the press have any meaning at all they mean a total exemption from any law making any publication whatever criminal.” In his 1801 inaugural address, Thomas Jefferson echoed Hay’s sentiments, stressing the necessity of preserving the right of citizens “to think freely and to speak and to write what they think.”

For most, the arguments of Hay and Jefferson have prevailed, although even the Republicans were willing to acknowledge that states could and should impose speech restrictions under certain conditions. Moreover, there have been occasions, most notably during World War I, when the federal government declared that free expression was secondary to military necessity. In an effort to suppress dissent and anti-war activity in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, a law that made it a felony to try to cause insubordination in the armed forces or to convey false statements with intent to interfere with military operations. It was followed by the Sedition Act of 1918, which banned treasonable or seditious material from the mail. Under this provision the mailing of many publications, including the New York Times as well as radical and dissident newspapers, was temporarily halted.

In the 200 years since the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, each generation of Americans has struggled to determine the limits of free speech and freedom of the press. In large part, it has been a dilemma of reconciling freedom and security with liberty and order. For the Federalist Party in 1798, however, the answer was simple; order and security had to prevail.

Larry Gragg, professor of history at the University of Missouri-Rolla, is the author of two books on the Virginia Quakers and the Salem witch crisis.

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

10 Pivotal Events in the Life of Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (1846-1917) led a signal life, from his youthful exploits with the Pony Express and in service as a U.S. Army scout to his globetrotting days as a showman and international icon Buffalo Bill.

During the War Years, Posters From the American Homefront Told You What to Do — And What Not to Do

If you needed some motivation during the war years, there was probably a poster for that.

Liberty And Order: A Clear But Delicate Balance

- James V. DeLong • 10/02/2001

- Telecommunications

In Defense of Freedom, an ad hoc group ("coalition" was thought to imply too much chumminess) of 130 organizations of wildly v

Delong Op-Ed in National Review Online

In Defense of Freedom, an ad hoc group ("coalition" was thought to imply too much chumminess) of 130 organizations of wildly varying basic views recently released a 10-point statement on the importance of defending civil liberties. Unanimity was possible only because the statement was all generalizations. "We can, as we have in the past, in times of war and of peace, reconcile the requirements of security with the demands of liberty," and so on.

These lofty sentiments are universally shared, but they provide little specific guidance. Suppose five people with Middle Eastern names board an airplane and the guard looks extra at their bags — racial profiling or common sense? The FBI wants wiretaps to cover a person rather than a single telephone — minor adaptation to the wireless era or octopus-like expansion of power? Should information on financial transactions collected by the government to cut off economic support to terrorists be passed on to the IRS or the drug enforcers? None of these issues were dealt with at the group's press conference, which was wise, since the occasion would have dissolved in mutual antipathies.

When not overly general, discussion tends to be ensnared in minutiae of civil-liberties jurisprudence. Constitutionally, the government can tap telephone calls only with a warrant issued upon "probable cause." However, it can upon mere suspicion install devices to capture the telephone numbers dialed. So how should capture devices be used on e-mail, where they pick up more than just the telephone numbers? Should the government get the deep link? The subject line? The issue is hotly debated.

A prime reason for the oscillation between the hopelessly abstract and the numbingly specific is that the authorities are charged with two different tasks, and, to anyone of common sense, the balance between liberty and order is different in each context.

One task is the investigation of crimes such as the recent attacks. This is a criminal case, and the normal principles apply — however horrendous the crime, it is as important that the innocent not be punished as that the guilty be called to account. Even here, however, our principles begin to bend. What might be regarded as probable cause for a warrant in the case of another crime, even a serious one, is not necessarily the same as probable cause in this case, as any sensible judge deciding on a warrant would recognize.

A second task is a combination of the prevention of further attacks and conduct of foreign affairs. We are at war, but we are having a problem figuring out who with. It is the job of the security agencies to find out. We also have good reason to believe that our foe is planning further actions. Most of us would rather not die, and if capturing the deep links on e-mails will save us, we would like to get the information, and be damned to minutiae of civil-liberties law. As anyone who did not go to law school understands immediately, prevention presents different issues than does prosecution.

What one thinks of any proposal depends on which function one has in mind. For example, civil-liberties groups are appalled that the FBI wants information on students who are from the Middle East or have had flight training. In the context of prevention, collecting such information is a sensible quick screen. But one's attitude changes if the effort turns into a dragnet for minor criminal violations, or the beginning of systematic surveillance.

Clearly, at the moment we need to focus on prevention, but we need — and lack — both legal doctrines and law-enforcement practices that recognize the extraordinary nature of the situation, and that allow some information to be collected and used only for prevention, or, if used for prosecution at all, used only in the context of terrorism.

The first need is for the government to recognize that prevention is indeed a different and special function, a state of mind which is not so far evident. For example, analogizing the antiterrorist effort to other criminal-justice "wars," such as the War on Drugs, is a mistake. How can one trust people who are indifferent to the distinction between preventing terrorism and preventing pot, or who refuse to recognize what a civil-liberties disaster that war is?

Nor has the government recognized the importance of keeping the law-enforcement community from using terrorism to expand its powers generally. The first-draft antiterrorist bill would have expanded asset forfeiture, which is already a cesspool of corruption, in all criminal cases, regardless of the connection to terrorism. The draft would also have made into special terrorist offenses some crimes that have nothing to with terrorism, such as illicit computer entry or firearms violations.

We also need to focus on institutional competence. Anyone who has worked for the government knows that every agency assumes its own competence and dedication. All failures are due to insufficient power or money. A crisis provides the chance to get more of both, immediately, and old wish lists are promptly resurrected.

This dynamic is already operating. FBI personnel were aware of suicide bombings in Israel, in possession of multiple reports of people connected with terrorist cells taking flight lessons, fully informed of a 1995 plot to blow up a number of airliners, and even familiar with the Tom Clancy novel is which a kamikaze pilot crashes an airliner into the Capitol. Yet officials given a specific report from a flight school that a man with known links to terrorists wanted lessons on how to steer a 767, but not to take off or land, "had no context in which his odd request made sense," according to the Washington Post.

The bureau's immediate response to the disaster is that it needs more driftnet power to collect more information about e-mail, computer keystrokes, or encrypted messages, and needs to shed irksome restrictions on warrants and wiretaps. This is unpersuasive, when the agency cannot coordinate and process what it already has.

Deep concern about the basic competence of other agencies is also in order. The FBI had Hanson but the CIA had Aldrich Ames. The CIA just revealed that the head of its Cuban desk was a spy. The INS cannot account for dozens of computers, including many holding secret information, an announcement that tracks a similar confession by the FBI a few months ago. The former head of the FAA gave the familiar "who could have imagined it?" to the use of an airliner as a bomb.

Again, emergency prevention powers may be needed; we are stuck with the organizations we have, and prevention is urgent. But nothing long term should be granted until there has been thorough organizational reform. Any new power should be limited by time and use restrictions.

A focus on prevention also highlights a need for error correction. For example, it is clear that people of Middle Eastern descent, especially non-citizens, will receive closer attention. This is common sense, not racial profiling. If the IRA becomes active in the U.S., the Irish will get special scrutiny.

We can fairly ask those subjected to this to tolerate it. But there is a quid pro quo. They must be treated courteously, efficiently, and apologetically, not only because of the demands of human decency and democratic values, but out of pragmatism. Middle Easterners are vital to the struggle because of their special knowledge. Many are in the U.S. because they prefer this society to that of their origin, and their experience makes them acutely aware of the stakes.

Those who get caught in the net unjustly should also be compensated generously for any harm they suffer. If the government holds someone as a material witness, all right — but pay his salary to his family. And if it ruins his business, pay him for it. Continuing judicial review of detention should ensure that investigators do not inhume their mistakes in jails.

An interesting parallel is Korematsu, the Supreme Court case upholding the government's 1942 order that Japanese Americans leave the West Coast. One can make a case that, contrary to all respectable opinion, the case was rightly decided. But a large reservation is necessary. Largely due to the dynamics of bureaucracy, the order was not rescinded even when it became obvious to the most cretinous both that Japan did not have the logistics to invade the U.S. and that any security risks in the evacuee population had been identified. The evacuees were not compensated for massive financial losses, and their welfare became a low-priority during the war, which left many of them stuck in internment camps.

These failures do not fit into the formal categories of the law, so they are never regarded as violations of civil liberties. All focus has been on the original order, as if once that is found to be valid the legal system has no further interest. But the subsequent failures, much more than the original decision, are cause for national embarrassment. A focus on prevention would emphasis that power need not be all or nothing; its exercise can be made highly conditional on ameliorating any injustices.

At a recent discussion, one participant commented: "I hope all of you who are so concerned about the details of civil liberties are aware that we are about one incident away from having very few." He is right, which makes it imperative that we hunt down and kill every vapid cliché and get serious about protecting civil liberty.

Copyright © 2001 National Review Online

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, the declaration, the constitution, and the bill of rights.

by Jeffrey Rosen and David Rubenstein

At the National Constitution Center, you will find rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. These are the three most important documents in American history. But why are they important, and what are their similarities and differences? And how did each document, in turn, influence the next in America’s ongoing quest for liberty and equality?

There are some clear similarities among the three documents. All have preambles. All were drafted by people of similar backgrounds, generally educated white men of property. The Declaration and Constitution were drafted by a congress and a convention that met in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (now known as Independence Hall) in 1776 and 1787 respectively. The Bill of Rights was proposed by the Congress that met in Federal Hall in New York City in 1789. Thomas Jefferson was the principal drafter of the Declaration and James Madison of the Bill of Rights; Madison, along with Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, was also one of the principal architects of the Constitution.

Most importantly, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are based on the idea that all people have certain fundamental rights that governments are created to protect. Those rights include common law rights, which come from British sources like the Magna Carta, or natural rights, which, the Founders believed, came from God. The Founders believed that natural rights are inherent in all people by virtue of their being human and that certain of these rights are unalienable, meaning they cannot be surrendered to government under any circumstances.

At the same time, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are different kinds of documents with different purposes. The Declaration was designed to justify breaking away from a government; the Constitution and Bill of Rights were designed to establish a government. The Declaration stands on its own—it has never been amended—while the Constitution has been amended 27 times. (The first ten amendments are called the Bill of Rights.) The Declaration and Bill of Rights set limitations on government; the Constitution was designed both to create an energetic government and also to constrain it. The Declaration and Bill of Rights reflect a fear of an overly centralized government imposing its will on the people of the states; the Constitution was designed to empower the central government to preserve the blessings of liberty for “We the People of the United States.” In this sense, the Declaration and Bill of Rights, on the one hand, and the Constitution, on the other, are mirror images of each other.

Despite these similarities and differences, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are, in many ways, fused together in the minds of Americans, because they represent what is best about America. They are symbols of the liberty that allows us to achieve success and of the equality that ensures that we are all equal in the eyes of the law. The Declaration of Independence made certain promises about which liberties were fundamental and inherent, but those liberties didn’t become legally enforceable until they were enumerated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In other words, the fundamental freedoms of the American people were alluded to in the Declaration of Independence, implicit in the Constitution, and enumerated in the Bill of Rights. But it took the Civil War, which President Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address called “a new birth of freedom,” to vindicate the Declaration’s famous promise that “all men are created equal.” And it took the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868 after the Civil War, to vindicate James Madison’s initial hope that not only the federal government but also the states would be constitutionally required to respect fundamental liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights—a process that continues today.

Why did Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence?

When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in 1775, it was far from clear that the delegates would pass a resolution to separate from Great Britain. To persuade them, someone needed to articulate why the Americans were breaking away. Congress formed a committee to do just that; members included John Adams from Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin from Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman from Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston from New York, and Thomas Jefferson from Virginia, who at age 33 was one of the youngest delegates.

Although Jefferson disputed his account, John Adams later recalled that he had persuaded Jefferson to write the draft because Jefferson had the fewest enemies in Congress and was the best writer. (Jefferson would have gotten the job anyway—he was elected chair of the committee.) Jefferson had 17 days to produce the document and reportedly wrote a draft in a day or two. In a rented room not far from the State House, he wrote the Declaration with few books and pamphlets beside him, except for a copy of George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and the draft Virginia Constitution, which Jefferson had written himself.

The Declaration of Independence has three parts. It has a preamble, which later became the most famous part of the document but at the time was largely ignored. It has a second part that lists the sins of the King of Great Britain, and it has a third part that declares independence from Britain and that all political connections between the British Crown and the “Free and Independent States” of America should be totally dissolved.

The preamble to the Declaration of Independence contains the entire theory of American government in a single, inspiring passage:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

When Jefferson wrote the preamble, it was largely an afterthought. Why is it so important today? It captured perfectly the essence of the ideals that would eventually define the United States. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” Jefferson began, in one of the most famous sentences in the English language. How could Jefferson write this at a time that he and other Founders who signed the Declaration owned slaves? The document was an expression of an ideal. In his personal conduct, Jefferson violated it. But the ideal—“that all men are created equal”—came to take on a life of its own and is now considered the most perfect embodiment of the American creed.

When Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address during the Civil War in November 1863, several months after the Union Army defeated Confederate forces at the Battle of Gettysburg, he took Jefferson’s language and transformed it into constitutional poetry. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” Lincoln declared. “Four score and seven years ago” refers to the year 1776, making clear that Lincoln was referring not to the Constitution but to Jefferson’s Declaration. Lincoln believed that the “principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society,” as he wrote shortly before the anniversary of Jefferson’s birthday in 1859. Three years later, on the anniversary of George Washington’s birthday in 1861, Lincoln said in a speech at what by that time was being called “Independence Hall,” “I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

It took the Civil War, the bloodiest war in American history, for Lincoln to begin to make Jefferson’s vision of equality a constitutional reality. After the war, the Declaration’s vision was embodied in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which formally ended slavery, guaranteed all persons the “equal protection of the laws,” and gave African-American men the right to vote. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, when supporters of gaining greater rights for women met, they, too, used the Declaration of Independence as a guide for drafting their Declaration of Sentiments. (Their efforts to achieve equal suffrage culminated in 1920 in the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.) And during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said in his famous address at the Lincoln Memorial, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In addition to its promise of equality, Jefferson’s preamble is also a promise of liberty. Like the other Founders, he was steeped in the political philosophy of the Enlightenment, in philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, Francis Hutcheson, and Montesquieu. All of them believed that people have certain unalienable and inherent rights that come from God, not government, or come simply from being human. They also believed that when people form governments, they give those governments control over certain natural rights to ensure the safety and security of other rights. Jefferson, George Mason, and the other Founders frequently spoke of the same set of rights as being natural and unalienable. They included the right to worship God “according to the dictates of conscience,” the right of “enjoyment of life and liberty,” “the means of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety,” and, most important of all, the right of a majority of the people to “alter and abolish” their government whenever it threatened to invade natural rights rather than protect them.

In other words, when Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and began to articulate some of the rights that were ultimately enumerated in the Bill of Rights, he wasn’t inventing these rights out of thin air. On the contrary, 10 American colonies between 1606 and 1701 were granted charters that included representative assemblies and promised the colonists the basic rights of Englishmen, including a version of the promise in the Magna Carta that no freeman could be imprisoned or destroyed “except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” This legacy kindled the colonists’ hatred of arbitrary authority, which allowed the King to seize their bodies or property on his own say-so. In the revolutionary period, the galvanizing examples of government overreaching were the “general warrants” and “writs of assistance” that authorized the King’s agents to break into the homes of scores of innocent citizens in an indiscriminate search for the anonymous authors of pamphlets criticizing the King. Writs of assistance, for example, authorized customs officers “to break open doors, Chests, Trunks, and other Packages” in a search for stolen goods, without specifying either the goods to be seized or the houses to be searched. In a famous attack on the constitutionality of writs of assistance in 1761, prominent lawyer James Otis said, “It is a power that places the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty officer.”

As members of the Continental Congress contemplated independence in May and June of 1776, many colonies were dissolving their charters with England. As the actual vote on independence approached, a few colonies were issuing their own declarations of independence and bills of rights. The Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, written by George Mason, began by declaring that “all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

When Jefferson wrote his famous preamble, he was restating, in more eloquent language, the philosophy of natural rights expressed in the Virginia Declaration that the Founders embraced. And when Jefferson said, in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, that “[w]hen in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another,” he was recognizing the right of revolution that, the Founders believed, had to be exercised whenever a tyrannical government threatened natural rights. That’s what Jefferson meant when he said Americans had to assume “the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.”

The Declaration of Independence was a propaganda document rather than a legal one. It didn’t give any rights to anyone. It was an advertisement about why the colonists were breaking away from England. Although there was no legal reason to sign the Declaration, Jefferson and the other Founders signed it because they wanted to “mutually pledge” to each other that they were bound to support it with “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” Their signatures were courageous because the signers realized they were committing treason: according to legend, after affixing his flamboyantly large signature John Hancock said that King George—or the British ministry—would be able to read his name without spectacles. But the courage of the signers shouldn’t be overstated: the names of the signers of the Declaration weren’t published until after General George Washington won crucial battles at Trenton and Princeton and it was clear that the war for independence was going well.

What is the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution?

In the years between 1776 and 1787, most of the 13 states drafted constitutions that contained a declaration of rights within the body of the document or as a separate provision at the beginning, many of them listing the same natural rights that Jefferson had embraced in the Declaration. When it came time to form a central government in 1776, the Continental Congress began to create a weak union governed by the Articles of Confederation. (The Articles of Confederation was sent to the states for ratification in 1777; it was formally adopted in 1781.) The goal was to avoid a powerful federal government with the ability to invade rights and to threaten private property, as the King’s agents had done with the hated general warrants and writs of assistance. But the Articles of Confederation proved too weak for bringing together a fledgling nation that needed both to wage war and to manage the economy. Supporters of a stronger central government, like James Madison, lamented the inability of the government under the Articles to curb the excesses of economic populism that were afflicting the states, such as Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, where farmers shut down the courts demanding debt relief. As a result, Madison and others gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 with the goal of creating a stronger, but still limited, federal government.

The Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia in the Pennsylvania State House, in the room where the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Jefferson, who was in France at the time, wasn’t among them. After four months of debate, the delegates produced a constitution.

During the final days of debate, delegates George Mason and Elbridge Gerry objected that the Constitution, too, should include a bill of rights to protect the fundamental liberties of the people against the newly empowered president and Congress. Their motion was swiftly—and unanimously—defeated; a debate over what rights to include could go on for weeks, and the delegates were tired and wanted to go home. The Constitution was approved by the Constitutional Convention and sent to the states for ratification without a bill of rights.

During the ratification process, which took around 10 months (the Constitution took effect when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify in late June 1788; the 13th state, Rhode Island, would not join the union until May 1790), many state ratifying conventions proposed amendments specifying the rights that Jefferson had recognized in the Declaration and that they protected in their own state constitutions. James Madison and other supporters of the Constitution initially resisted the need for a bill of rights as either unnecessary (because the federal government was granted no power to abridge individual liberty) or dangerous (since it implied that the federal government had the power to infringe liberty in the first place). In the face of a groundswell of popular demand for a bill of rights, Madison changed his mind and introduced a bill of rights in Congress on June 8, 1789.

Madison was least concerned by “abuse in the executive department,” which he predicted would be the weakest branch of government. He was more worried about abuse by Congress, because he viewed the legislative branch as “the most powerful, and most likely to be abused, because it is under the least control.” (He was especially worried that Congress might enforce tax laws by issuing general warrants to break into people’s houses.) But in his view “the great danger lies rather in the abuse of the community than in the legislative body”—in other words, local majorities who would take over state governments and threaten the fundamental rights of minorities, including creditors and property holders. For this reason, the proposed amendment that Madison considered “the most valuable amendment in the whole list” would have prohibited the state governments from abridging freedom of conscience, speech, and the press, as well as trial by jury in criminal cases. Madison’s favorite amendment was eliminated by the Senate and not resurrected until after the Civil War, when the 14th Amendment required state governments to respect basic civil and economic liberties.

In the end, by pulling from the amendments proposed by state ratifying conventions and Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, Madison proposed 19 amendments to the Constitution. Congress approved 12 amendments to be sent to the states for ratification. Only 10 of the amendments were ultimately ratified in 1791 and became the Bill of Rights. The first of the two amendments that failed was intended to guarantee small congressional districts to ensure that representatives remained close to the people. The other would have prohibited senators and representatives from giving themselves a pay raise unless it went into effect at the start of the next Congress. (This latter amendment was finally ratified in 1992 and became the 27th Amendment.)

To address the concern that the federal government might claim that rights not listed in the Bill of Rights were not protected, Madison included what became the Ninth Amendment, which says the “enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” To ensure that Congress would be viewed as a government of limited rather than unlimited powers, he included the 10th Amendment, which says the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Because of the first Congress’s focus on protecting people from the kinds of threats to liberty they had experienced at the hands of King George, the rights listed in the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights apply only to the federal government, not to the states or to private companies. (One of the amendments submitted by the North Carolina ratifying convention but not included by Madison in his proposal to Congress would have prohibited Congress from establishing monopolies or companies with “exclusive advantages of commerce.”)

But the protections in the Bill of Rights—forbidding Congress from abridging free speech, for example, or conducting unreasonable searches and seizures—were largely ignored by the courts for the first 100 years after the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. Like the preamble to the Declaration, the Bill of Rights was largely a promissory note. It wasn’t until the 20th century, when the Supreme Court began vigorously to apply the Bill of Rights against the states, that the document became the centerpiece of contemporary struggles over liberty and equality. The Bill of Rights became a document that defends not only majorities of the people against an overreaching federal government but also minorities against overreaching state governments. Today, there are debates over whether the federal government has become too powerful in threatening fundamental liberties. There are also debates about how to protect the least powerful in society against the tyranny of local majorities.

What do we know about the documentary history of the rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights on display at the National Constitution Center?

Generally, when people think about the original Declaration, they are referring to the official engrossed —or final—copy now in the National Archives. That is the one that John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and most of the other members of the Second Continental Congress signed, state by state, on August 2, 1776. John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, published the official printing of the Declaration ordered by Congress, known as the Dunlap Broadside, on the night of July 4th and the morning of July 5th. About 200 copies are believed to have been printed. At least 27 are known to survive.

The document on display at the National Constitution Center is known as a Stone Engraving, after the engraver William J. Stone, whom then Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned in 1820 to create a precise facsimile of the original engrossed version of the Declaration. That manuscript had become faded and worn after nearly 45 years of travel with Congress between Philadelphia, New York City, and eventually Washington, D.C., among other places, including Leesburg, Virginia, where it was rolled up and hidden during the British invasion of the capital in 1814.

To ensure that future generations would have a clear image of the original Declaration, William Stone made copies of the document before it faded away entirely. Historians dispute how Stone rendered the facsimiles. He kept the original Declaration in his shop for up to three years and may have used a process that involved taking a wet cloth, putting it on the original document, and creating a perfect copy by taking off half the ink. He would have then put the ink on a copper plate to do the etching (though he might have, instead, traced the entire document by hand without making a press copy). Stone used the copper plate to print 200 first edition engravings as well as one copy for himself in 1823, selling the plate and the engravings to the State Department. John Quincy Adams sent copies to each of the living signers of the Declaration (there were three at the time), public officials like President James Monroe, Congress, other executive departments, governors and state legislatures, and official repositories such as universities. The Stone engravings give us the clearest idea of what the original engrossed Declaration looked like on the day it was signed.

The Constitution, too, has an original engrossed, handwritten version as well as a printing of the final document. John Dunlap, who also served as the official printer of the Declaration, and his partner David C. Claypoole, who worked with him to publish the Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser , America’s first successful daily newspaper founded by Dunlap in 1771, secretly printed copies of the convention’s committee reports for the delegates to review, debate, and make changes. At the end of the day on September 15, 1787, after all of the delegations present had approved the Constitution, the convention ordered it engrossed on parchment. Jacob Shallus, assistant clerk to the Pennsylvania legislature, spent the rest of the weekend preparing the engrossed copy (now in the National Archives), while Dunlap and Claypoole were ordered to print 500 copies of the final text for distribution to the delegates, Congress, and the states. The engrossed copy was signed on Monday, September 17th, which is now celebrated as Constitution Day.

The copy of the Constitution on display at the National Constitution Center was published in Dunlap and Claypoole’s Pennsylvania Packet newspaper on September 19, 1787. Because it was the first public printing of the document—the first time Americans saw the Constitution—scholars consider its constitutional significance to be especially profound. The publication of the Constitution in the Pennsylvania Packet was the first opportunity for “We the People of the United States” to read the Constitution that had been drafted and would later be ratified in their name.

The handwritten Constitution inspires awe, but the first public printing reminds us that it was only the ratification of the document by “We the People” that made the Constitution the supreme law of the land. As James Madison emphasized in The Federalist No. 40 in 1788, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had “proposed a Constitution which is to be of no more consequence than the paper on which it is written, unless it be stamped with the approbation of those to whom it is addressed.” Only 25 copies of the Pennsylvania Packet Constitution are known to have survived.

Finally, there is the Bill of Rights. On October 2, 1789, Congress sent 12 proposed amendments to the Constitution to the states for ratification—including the 10 that would come to be known as the Bill of Rights. There were 14 original manuscript copies, including the one displayed at the National Constitution Center—one for the federal government and one for each of the 13 states.

Twelve of the 14 copies are known to have survived. Two copies —those of the federal government and Delaware — are in the National Archives. Eight states currently have their original documents; Georgia, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania do not. There are two existing unidentified copies, one held by the Library of Congress and one held by The New York Public Library. The copy on display at the National Constitution Center is from the collections of The New York Public Library and will be on display for several years through an agreement between the Library and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; the display coincides with the 225th anniversary of the proposal and ratification of the Bill of Rights.

The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are the three most important documents in American history because they express the ideals that define “We the People of the United States” and inspire free people around the world.

Read More About the Constitution

The constitutional convention of 1787: a revolution in government, on originalism in constitutional interpretation, democratic constitutionalism, modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle

- Lance Banning (editor)

An anthology of primary sources which documents the first great party struggle in American history between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists over the proper construction of the new Constitution, political economy, the appropriate level of popular participation in a republican polity, and foreign policy.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- LF Printer PDF This text-based PDF was prepared by the typesetters of the LF book.

Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle, ed. and with a Preface by Lance Banning (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2004).

The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

- Political Institutions and Public Administration (United States)

Related Collections:

- Introduction to the Study of Liberty - Works to Begin with

- Freedom of Speech

- American Revolution and Constitution

- Primary Sources

- Books Published by Liberty Fund

- Textbooks published by Liberty Fund

- Liberty Fund E-Books

Parties & Elections

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Locke On Freedom

John Locke’s views on the nature of freedom of action and freedom of will have played an influential role in the philosophy of action and in moral psychology. Locke offers distinctive accounts of action and forbearance, of will and willing, of voluntary (as opposed to involuntary) actions and forbearances, and of freedom (as opposed to necessity). These positions lead him to dismiss the traditional question of free will as absurd, but also raise new questions, such as whether we are (or can be) free in respect of willing and whether we are free to will what we will, questions to which he gives divergent answers. Locke also discusses the (much misunderstood) question of what determines the will, providing one answer to it at one time, and then changing his mind upon consideration of some constructive criticism proposed by his friend, William Molyneux. In conjunction with this change of mind, Locke introduces a new doctrine (concerning the ability to suspend the fulfillment of one’s desires) that has caused much consternation among his interpreters, in part because it threatens incoherence. As we will see, Locke’s initial views do suffer from clear difficulties that are remedied by his later change of mind, all without introducing incoherence.

Note on the text: Locke’s theory of freedom is contained in Book II, Chapter xxi of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding . The chapter underwent five revisions in Locke’s lifetime [E1 (1689), E2 (1694), E3 (1695), E4 (1700), and E5 (1706)], with the last edition published posthumously. Significant changes, including a considerable lengthening of the chapter, occur in E2; and important changes appear in E5.

1. Actions and Forbearances

2. will and willing, 3. voluntary vs. involuntary action/forbearance, 4. freedom and necessity, 5. free will, 6. freedom in respect of willing, 7. freedom to will, 8. determination of the will, 9. the doctrine of suspension, 10. compatibilism or incompatibilism, select primary sources, select secondary sources, additional secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries.

For Locke, the question of whether human beings are free is the question of whether human beings are free with respect to their actions and forbearances . As he puts it:

[T]he Idea of Liberty , is the Idea of a Power in any Agent to do or forbear any Action, according to the determination or thought of the mind, whereby either of them is preferr’d to the other. (E1–4 II.xxi.8: 237)

In order to understand Locke’s conception of freedom, then, we need to understand his conception of action and forbearance.

There are three main accounts of Locke’s theory of action. According to what we might call the “Doing” theory of action, actions are things that we do (actively), as contrasted to things that merely happen to us (passively). If someone pushes my arm up, then my arm rises, but, one might say, I did not raise it. That my arm rose is something that happened to me, not something I did . By contrast, when I signal to a friend who has been looking for me, I do something inasmuch as I am not a mere passive recipient of a stimulus over which I have no control. According to some interpreters (e.g., Stuart 2013: 405, 451), Locke’s actions are doings in this sense. According to the “Composite” or “Millian” theory of action, an action is “[n]ot one thing, but a series of two things; the state of mind called a volition, followed by an effect” (Mill 1974 [1843]: 55). On this view, for example, the action of raising my hand is composed of (i) willing to produce the effect of my hand’s rising and (ii) the effect itself, where (ii) results from (i). According to some interpreters (arguably, Lowe 1986: 120–121; Lowe 1995: 141—though it is possible that Lowe’s theory applies only to voluntary actions), Locke’s actions are composite in this sense. Finally, according to what we might call the “Deflationary” conception of action, actions are simply motions of bodies or operations of minds.

Some of what Locke says suggests that he holds the “Doing” theory of action: “when [a Body] is set in motion it self, that Motion is rather a Passion, than an Action in it”, for “when the Ball obeys the stroke of a Billiard-stick, it is not any action of the Ball, but bare passion” (E1–5 II.xxi.4: 235—see also E4–5 II.xxi.72: 285–286). Here Locke is clearly working with a sense of “action” according to which actions are opposed to passions. But, on reflection, it is unlikely that this is what Locke means by “action” when he writes about voluntary/involuntary actions and freedom of action. For Locke describes “a Man striking himself, or his Friend, by a Convulsive motion of his Arm, which it is not in his Power…to…forbear” as “acting” (E1–5 II.xxi.9: 238), and describes the convulsive leg motion caused by “that odd Disease called Chorea Sancti Viti [St. Vitus’s Dance]” as an “Action” (E1–5 II.xxi.11: 239). It would be a mistake to think of these convulsive motions as “doings”, for they are clearly things that “happen” to us in just the way that it happens to me that my arm rises when someone else raises it. Examples of convulsive actions also suggest that the Millian account of Locke’s theory of action is mistaken. For in the case of convulsive motion, there is no volition that one’s limbs move; indeed, if there is volition in such cases, it is usually a volition that one’s limbs not move. Such actions, then, cannot be composed of a volition and the motion that is willed, for the relevant volition is absent (more on volition below).

We are therefore left with the Deflationary conception of action, which is well supported by the text. There are, Locke says, “but two sorts of Action, whereof we have any Idea , viz. Thinking and Motion” (E1–5 II.xxi.4: 235—see also E1–5 II.xxi.8: 237 and E4–5 II.xxi.72: 285); “Thinking, and Motion…are the two Ideas which comprehend in them all Action” (E1–5 II.xxii.10: 293). It may be that, in the sense in which “action” is opposed to “passion”, some corporeal motions and mental operations, being produced by external causes rather than self-initiated, are not actions. But that is not the sense in which all motions and thoughts are “called and counted Actions ” in Locke’s theory of action (E4–5 II.xxi.72: 285). As seems clear, convulsive motions are actions inasmuch as they are motions, and thoughts that occur in the mind unbidden are actions inasmuch as they are mental operations.

What, then, according to Locke, are forbearances? On some interpretations (close counterparts to the Millian conception of action), Locke takes forbearances to be voluntary not-doings (e.g., Stuart 2013: 407) or voluntary omissions to act (e.g., Lowe 1995: 123). There are texts that suggest as much:

sitting still , or holding one’s peace , when walking or speaking are propos’d, [are] mere forbearances, requiring…the determination of the Will . (E2–5 II.xxi.28: 248)

However, Locke distinguishes between voluntary and involuntary forbearances (E2–5 II.xxi.5: 236), and it makes no sense to characterize an involuntary forbearance as an involuntary voluntary not-doing. So it is unlikely that Locke thinks of forbearances as voluntary not-doings. This leaves the Deflationary conception of forbearance, according to which a forbearance is the opposite of an action, namely an episode of rest or absence of thought. On this conception, to say that someone forbore running is to say that she did not run, not that she voluntarily failed to run. Every forbearance would be an instance of inaction, not a refraining.

In E2–5, Locke stipulates that he uses the word “action” to “comprehend the forbearance too of any Action proposed”, in order to “avoid the multiplying of words” (E2–5 II.xxi.28: 248). The reason he so stipulates is not that he literally takes forbearances to be actions (as he puts it, they “pass for” actions), but that most everything that he wants to say about actions (in particular, the distinction between voluntary and involuntary actions, and the account of freedom of action) applies pari passu to forbearances (see below).

Within the category of actions, Locke distinguishes between those that are voluntary and those that are involuntary. To understand this distinction, we need to understand Locke’s account of the will and his account of willing (or volition). For Locke, the will is a power (ability, faculty—see E1–5 II.xxi.20: 244) possessed by a person (or by that person’s mind). Locke explains how we come by the idea of power (in Humean vein, as the result of observation of constant conjunctions—“like Changes [being] made, in the same things, by like Agents, and by the like ways” (E1–5 II.xxi.1: 233)), but does not offer a theory of the nature of power. What we are told is that “ Powers are Relations” (E1–5 II.xxi.19: 243), relations “to Action or Change” (E1–5 II.xxi.3: 234), and that powers are either active (powers to make changes) or passive (powers to receive changes) (E1–5 II.xxi.2: 234). In this sense, the will is an active relation to actions.

Locke’s predecessors had thought of the will as intimately related to the faculty of desire or appetite. For the Scholastics (whose works Locke read as a student at Oxford), the will is the power of rational appetite. For Thomas Hobbes (by whom Locke was deeply influenced even though this was not something he could advertise, because Hobbes was a pariah in Locke’s intellectual and political circles), the will is simply the power of desire itself. Remnants of this desiderative conception of the will remain in Locke’s theory, particularly in the first edition of the Essay . Here, for example, is Locke’s official E1 account of the will:

This Power the Mind has to prefer the consideration of any Idea to the not considering it; or to prefer the motion of any part of the body to its rest. (E1 II.xxi.5: 236)

And here is Locke’s official E1 account of preferring:

Well, but what is this Preferring ? It is nothing but the being pleased more with the one , than the other . (E1 II.xxi.28: 248)

So, in E1, the will is the mind’s power to be more pleased with the consideration of an idea than with the not considering it, or to be more pleased with the motion of a part of one’s body than with its remaining at rest. When we lack something that would deliver more pleasure than we currently experience, we become uneasy at its absence. And this kind of uneasiness (or pain: E1–5 II.vii.1: 128), is what Locke describes as desire (E1–5 II.xx.6: 230; E2–5 II.xxi.31–32: 251) (though also as “joined with”, “scarce distinguishable from”, and a “cause” of desire—see Section 8 below). So, in E1, the will is the mind’s power to desire or want the consideration of an idea more than the not considering it, or to desire or want the motion of a part of one’s body more than its remaining at rest. (At E2–5 II.xxi.5: 236, Locke adds “and vice versâ ”, to clarify that it can also happen, even according to the E1 account, that one prefers not considering an idea to considering it, or not moving to moving.) [ 1 ]

In keeping with this conception of the will as desire, Locke in E1 then defines an exercise of the will, which he calls “willing” or “volition”, as an “actual preferring” of one thing to another (E1 II.xxi.5: 236). For example, I have the power to prefer the upward motion of my arm to its remaining at rest by my side. This power, in E1, is one aspect of my will. When I exercise this power, I actually prefer the upward motion of my arm to its remaining at rest, i.e., I am more pleased with my arm’s upward motion than I am with its continuing to rest. This is what Locke, in E1, thinks of as my willing the upward motion of my arm (or, as he sometimes puts it, my willing or volition to move my arm upward ).

In E2–5, Locke explicitly gives up this conception of the will and willing, explaining why he does so, making corresponding changes in the text of the Essay , even while leaving passages that continue to suggest the desiderative conception. He writes: “[T]hough a Man would preferr flying to walking, yet who can say he ever wills it?” (E2–5 II.xxi.15: 241). The thought here is that, as Locke (rightly) recognizes, my being more pleased with flying than walking does not consist in (or even entail) my willing to fly. This is in large part because it is necessarily implied in willing motion of a certain sort that one exert dominion that one takes oneself to have (E2–5 II.xxi.15: 241), that “the mind [endeavor] to give rise…to [the motion], which it takes to be in its power” (E2–5 II.xxi.30: 250). So if I do not believe that it is in my power to fly, then it is impossible for me to will the motion of flying, even though I might be more pleased with flying than I am with any alternative. Locke concludes (with the understatement) that “ Preferring which seems perhaps best to express the Act of Volition , does it not precisely” (E2–5 II.xxi.15: 240–241).

In addition, Locke points out that it is possible for “the Will and Desire [to] run counter”. For example, as a result of being coerced or threatened, I might will to persuade someone of something, even though I desire that I not succeed in persuading her. Or, suffering from gout, I might desire to be eased of the pain in my feet, and yet at the same time, recognizing that the translation of such pain would affect my health for the worse, will that I not be eased of my foot pain. In concluding that “ desiring and willing are two distinct Acts of the mind”, Locke must be assuming (reasonably) that it is not possible to will an action and its contrary at the same time (E2–5 II.xxi.30: 250). [ 2 ]

With what conception of the will and willing does Locke replace the abandoned desiderative conception? The answer is that in E2–5 Locke describes the will as a kind of directive or commanding faculty, the power to direct (or issue commands to) one’s body or mind: it is, he writes,

a Power to begin or forbear, continue or end several actions of our minds, and motions of our Bodies, barely by a thought or preference of the mind ordering, or as it were commanding the doing or not doing such or such particular action. (E2–5 II.xxi.5: 236)

Consonant with this non-desiderative, directive conception of the will, Locke claims that

Volition , or Willing , is an act of the Mind directing its thought to the production of any Action, and thereby exerting its power to produce it, (E2–5 II.xxi.28: 248)

Volition is nothing, but that particular determination of the mind, whereby, barely by a thought, the mind endeavours to give rise, continuation, or stop to any Action, which it takes to be in its power. (E2–5 II.xxi.30: 250)

Every volition, then, is a volition to act or to forbear , where willing to act is a matter of commanding one’s body to move or one’s mind to think, and willing to forbear is a matter of commanding one’s body to rest or one’s mind not to think. Unlike a desiderative power, which is essentially passive (as involving the ability to be more pleased with one thing than another), the will in E2–5 is an intrinsically active power, the exercise of which involves the issuing of mental commands directed at one’s own body and mind.

Within the category of actions/forbearances, Locke distinguishes between those that are voluntary and those that are involuntary. Locke does not define voluntariness and involuntariness in E1, but he does in E2–5:

The forbearance or performance of [an] action, consequent to such order or command of the mind is called Voluntary . And whatsoever action is performed without such a thought of the mind is called Involuntary . (E2–4 II.xxi.5: 236—in E5, “or performance” is omitted from the first sentence)

Locke is telling us that what makes an action/forbearance voluntary is that it is consequent to a volition, and that what makes an action/forbearance involuntary is that it is performed without a volition. The operative words here are “consequent to” and “without”. What do they mean? (Henceforth, following Locke’s lead, I will not distinguish between actions and forbearances unless the context calls for it.)

We can begin with something Locke says only in E1:

Volition, or the Act of Willing, signifies nothing properly, but the actual producing of something that is voluntary. (E1 II.xxi.33: 259)

On reflection, this is mistaken, but it does provide a clue to Locke’s conception of voluntariness. The mistake (of which Locke likely became aware, given that the statement clashes with the rest of his views and was removed from E2–5) is that not every instance of willing an action is followed by the action itself. To use one of Locke’s own examples, if I am locked in a room and will to leave, my volition will not result in my leaving (E1–5 II.xxi.10: 238). So willing cannot signify the “actual producing” of a voluntary action. However, it is reasonable to assume that, for Locke, willing will “produce” a voluntary action if nothing hinders the willed episode of motion or thought. And this makes it likely that Locke takes a voluntary action to be not merely temporally consequent to, but actually caused by, the right kind of volition (Yaffe 2000; for a contrary view, see Hoffman 2005).