An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Biology of Viruses and Viral Diseases

James d chappell, terence s dermody.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Issue date 2015.

Keywords: antiviral, apoptosis, cancer, innate immunity, pathogenesis, receptor, tropism, vaccine, virulence, virus

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

Viruses exact an enormous toll on the human population and are the single most important cause of infectious disease morbidity and mortality worldwide. Viral diseases in humans were first noted in ancient times and have since shaped our history. Scientific approaches to the study of viruses and viral disease began in the 19th century and led to the identification of specific disease entities caused by viruses. Careful clinical observations enabled the identification of many viral illnesses and allowed several viral diseases to be differentiated (e.g., smallpox vs. chickenpox and measles vs. rubella). Progress in an understanding of disease at the level of cells and tissues, exemplified by the pioneering work of Virchow, allowed the pathology of many viral diseases to be defined. Finally, the work of Pasteur ushered in the systematic use of laboratory animals for studies of the pathogenesis of infectious diseases, including those caused by viruses.

The first viruses were identified as the 19th century ended. Ivanovsky and Beijerinck identified tobacco mosaic virus, and Loeffler and Frosch discovered foot-and-mouth disease virus. These observations were quickly followed by the discovery of yellow fever virus and the seminal research on the pathogenesis of yellow fever by Walter Reed and the U. S. Army Yellow Fever Commission. 1 By the end of the 1930s, tumor viruses, bacteriophages, influenza virus, mumps virus, and many arthropod-borne viruses had been identified. This process of discovery has continued with growing momentum to the present, with recently identified skin cancer–associated Merkel cell polyomavirus, 2 novel Old World arenaviruses causing fatal disease, 3 , 4 bat-related respiratory coronavirus 5 and reoviruses, 6 , 7 and novel swine- and avian-origin influenza viruses 8 , 9 counted among the most recent entries in the catalog of human disease-causing viruses.

In the 1940s, Delbruck, Luria, and others 10 , 11 used bacteriophages as models to establish many basic principles of microbial genetics and molecular biology and identified key steps in viral replication. The pioneering experiments of Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty 12 on the transformation of pneumococci established DNA as the genetic material and set the stage for corroborating experiments by Hershey and Chase using bacteriophages. 13 In the late 1940s, Enders and colleagues 14 cultivated poliovirus in tissue culture. This accomplishment led to the development of both formalin-inactivated (Salk) 15 and live-attenuated (Sabin) 16 vaccines for polio and ushered in the modern era of experimental and clinical virology.

In recent years, x-ray crystallography has allowed visualization of virus structures at an atomic level of resolution. Nucleotide sequences of entire genomes of most human viruses are known, and functional domains of many viral structural and enzymatic proteins have been defined. This information is being applied to the development of new strategies to diagnose viral illnesses and design effective antiviral therapies. Techniques to detect viral genomes, such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its derivatives, have proven superior to conventional serologic assays and culture techniques for the diagnosis of many viral diseases. Nucleic acid–based strategies are now used routinely in the diagnosis of infections caused by enteroviruses, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), herpesviruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and, with increasing frequency, respiratory and enteric viral pathogens. Furthermore, rapid developments in mass spectrometry and nucleotide sequencing technology are permitting the application of these tools to highly sensitive and specific virus detection in clinical specimens.

Perhaps an even more exciting development is the means to introduce new genetic material into viral genomes. Strategies now exist whereby specific mutations or even entire genes can be inserted into the genomes of many viruses. Such approaches can be exploited in the rational design of vaccines and the development of viral vectors for use in gene delivery. Furthermore, these powerful new techniques are leading to breakthroughs in foundational problems in viral pathogenesis, such as the nature of virus–cell interactions that produce disease, immunoprotective and immunopathologic host responses to infection, and viral and host determinants of contagion. Improved understanding of these aspects of viral infection will facilitate new approaches to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of viral diseases.

Virus Structure and Classification

The first classification of viruses as a group distinct from other microorganisms was based on the capacity to pass through filters of a small pore size (filterable agents). Initial subclassifications were based primarily on pathologic properties such as specific organ tropism (e.g., hepatitis viruses) or common epidemiologic features such as transmission by arthropod vectors (e.g., arboviruses). Current classification systems are based on the following: (1) the type and structure of the viral nucleic acid and the strategy used in its replication; (2) the type of symmetry of the virus capsid (helical vs. icosahedral); and (3) the presence or absence of a lipid envelope ( Table 134-1 ).

TABLE 134-1.

Classification of Viruses

(+), message sense; (−), complement of message sense; DS, double-stranded; H, helical; I, icosahedral; S, spherical; SS, single-stranded.

Reovirus and orbivirus, 10 segments; rotavirus, 11 segments; Colorado tick fever virus, 12 segments.

Data from Condit RC. Principles of virology. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields Virology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Press; 2007:25-57.

Virus particles—virions—can be functionally conceived as a delivery system that surrounds a payload. The delivery system consists of structural components used by the virus to survive in the environment and bind to host cells. The payload contains the viral genome and often includes enzymes required for the initial steps in viral replication. In almost all cases, the delivery system must be removed from the virion to allow viral replication to commence.

In addition to mediating attachment to host cells, the delivery system also plays a crucial role in determining the mode of transmission between hosts. Viruses containing lipid envelopes are sensitive to desiccation in the environment and, for the most part, are transmitted by the respiratory, parenteral, and sexual routes. Nonenveloped viruses are stable to harsh environmental conditions and are often transmitted by the fecal-oral route.

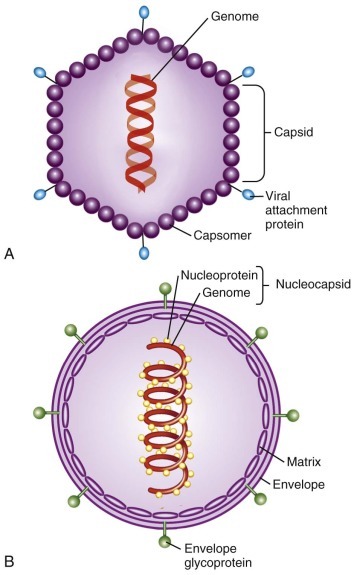

Viral genomes exist in a variety of forms and sizes and consist of RNA or DNA (see Table 134-1 ). Animal virus genomes range in size from 3 kb, encoding only three or four proteins in small viruses such as the hepadnaviruses, to more than 300 kb, encoding several hundred proteins in large viruses such as the poxviruses. Viral genomes are single- or double-stranded and circular or linear. RNA genomes are composed of a single molecule of nucleic acid or multiple discrete segments, which can vary in number from as few as two in the arenaviruses up to 12 in some members of the Reoviridae. Viral nucleic acid is packaged in a protein coat, or capsid, that consists of multiple protein subunits. The combination of the viral nucleic acid and the surrounding protein capsid is often referred to as the nucleocapsid ( Fig. 134-1 ).

FIGURE 134-1.

Schematic diagrams illustrating the structure of a nonenveloped icosahedral virus (A) and an enveloped helical virus (B). Nucleocapsid: combination of a viral nucleic acid and surrounding protein capsid.

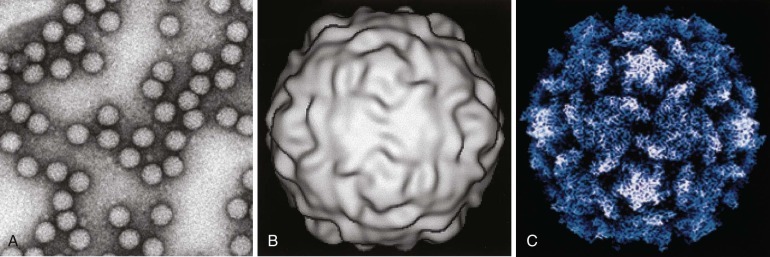

Structural details of many viruses have now been defined at an atomic level of resolution ( Fig. 134-2 ). General features of virus structure can be gained from examination of electron micrographs of negatively stained virions and thin-section electron micrographs of virus-infected tissues and cultured cells. These techniques allow rapid identification of viral size, shape, symmetry, and surface features, presence or absence of an envelope, and intracellular site of viral assembly. Cryoelectron microscopy and computer image processing techniques are used to determine the three-dimensional structures of spherical viruses at a level of resolution far superior to that of negatively stained electron micrographs. A major advantage of cryoelectron microscopy is that it allows structural studies of viruses to be performed under conditions that do not alter native virion structure. Moreover, recent advances in cryoelectron microscopy have extended the achievable resolution of particle-associated proteins to near-atomic levels, sufficient to recognize characteristic features of secondary structural elements. 17 Image reconstructions of cryoelectron micrographs, sometimes in combination with x-ray crystallography, can also be used to investigate structural aspects of various virus functions, including receptor binding 18 , 19 , 20 and interaction with antibodies. 21 , 22 Identification of key motifs, such as receptor binding sites or immunodominant domains, provides the framework for understanding the structural basis of virus–cell interactions. Electron tomography with image reconstruction has been applied to architectural studies of viruses and intracellular foci of virus replication, rendering exquisite three-dimensional representations of particle organization and revealing the structure and subcellular origins of virus manufacturing centers. 23 , 24

FIGURE 134-2.

Structural studies of poliovirus.

A, Negative-stained electron micrograph. B, Three-dimensional image reconstruction of cryoelectron micrographs. C, Structure determined by x-ray crystallography.

(Courtesy Dr. James Hogle, Harvard University.)

A number of general principles have emerged from studies of virus structure. In almost all cases, the capsid is composed of a repeating series of structurally similar subunits, each of which in turn is composed of only a few different proteins. The parsimonious use of structural proteins in a repetitive motif minimizes the amount of genetic information required to encode the viral capsid and leads to structural arrangements with symmetrical features. All but the most complex viruses exhibit either helical or icosahedral symmetry (see Table 134-1 ). Viruses with helical symmetry contain repeating protein subunits bound at regular intervals along a spiral formed by the viral nucleic acid. Interestingly, all known animal viruses that show this type of symmetry have RNA genomes. Viruses with icosahedral symmetry display twofold, threefold, and fivefold axes of rotational symmetry, and viral nucleic acid is intimately associated with specific capsid proteins in an ordered packing arrangement.

The use of repeating subunits with symmetrical protein-protein interactions facilitates the assembly of the viral capsid. In most cases, viral assembly appears to be a spontaneous process that occurs under the appropriate physiologic conditions and often can be reproduced when recombinant viral proteins are expressed in the absence of viral replication. 25 , 26 For many viruses, assembly of the capsid proceeds through a series of intermediates, each of which nucleates the addition of subsequent components in the assembly sequence.

One of the most poorly understood aspects of viral assembly is the process that ensures that the viral nucleic acid is correctly packaged into the capsid. In the case of viruses with helical symmetry, there may be an initiation site on the nucleic acid to which the initial capsid protein subunit binds, triggering the addition of subsequent subunits. The genomes of most DNA-containing viruses are inserted into preassembled capsid intermediates (procapsids) through adenosine triphosphate–driven mechanisms. 27 In preparations of many icosahedral viruses, empty capsids (i.e., capsids lacking nucleic acid) are frequently observed, indicating that assembly may proceed to completion without a requirement for the viral genome.

In some viruses, the nucleocapsid is surrounded by a lipid envelope acquired as the virus particle buds from the host cell cytoplasmic, nuclear, or endoplasmic reticular membrane (see Fig. 134-1 ). Inserted into this lipid bilayer are virus-encoded proteins (e.g., the hemagglutinin [HA] and neuraminidase proteins of influenza virus and gp41 and gp120 of HIV), which are exposed on the surface of the virus particle. These viral proteins usually contain a glycosylated hydrophilic external portion and internal hydrophobic domains that span the lipid membrane and anchor the protein into the viral envelope. In some cases, another viral protein, often termed a matrix protein, associates with the internal (cytoplasmic) surface of the lipid envelope, where it can interact with the cytoplasmic domains of the envelope glycoproteins. Matrix proteins may play roles in stabilizing the interaction between viral glycoproteins and the lipid envelope, directing the viral genome to intracellular sites of viral assembly, or facilitating viral budding. Matrix proteins can also influence a diverse set of cellular functions, such as inhibition of host cell transcription 28 , 29 and evasion of the cellular innate antiviral response. 30

Virus–Cell Interactions

Viruses require an intact cell to replicate and can direct the synthesis of hundreds to thousands of progeny viruses during a single cycle of infection. In contrast to other microorganisms, viruses do not replicate by binary fission. Instead, the infecting particle must disassemble in order to direct synthesis of viral progeny.

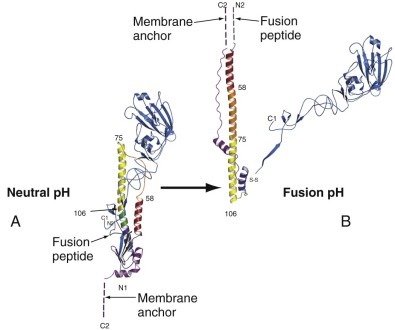

The interaction between a virus and its host cell begins with attachment of the virus particle to specific receptors on the cell surface. Viral proteins that mediate the attachment function (viral attachment proteins) include the following: single-capsid components that extend from the virion surface, such as the attachment proteins of adenovirus, 31 reovirus, 32 and rotavirus 33 , 34 ; surface glycoproteins of enveloped viruses, such as influenza virus 35 , 36 ( Fig. 134-3 ) and HIV 37 , 38 ; viral capsid proteins that form binding pockets that engage cellular receptors, such as the canyon formed by the capsid proteins of poliovirus 39 and rhinovirus 40 ; and viral capsid proteins that contain extended loops capable of binding receptors, such as foot-and-mouth disease virus. 41 Studies of the attachment of several diverse virus groups, including adenoviruses, coronaviruses, herpesviruses, lentiviruses, and reoviruses, indicate that multiple interactions between virus and cell occur during the attachment step. These observations indicate that a specific sequence of binding events between virus and cell optimizes specificity and contributes significant stability to the association. 42

FIGURE 134-3.

The folded structure of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) and its rearrangement when exposed to low pH.

A, The HA monomer. HA1 is blue, and HA2 is multicolored. The receptor-binding pocket resides in the virion-distal portion of HA1. The viral membrane would be at the bottom of this figure. B, Conformational change in HA induced by exposure to low pH. Note the dramatic structural rearrangement in HA2, in which amino acid residues 40-105 become a continuous alpha helix. Dashed lines indicate regions of undetermined structure. This model of HA in its fusion conformation is a composite of the HA1 domain structure and the low-pH HA2 structure.

(Modified from Russell RJ, Kerry PS, Stevens DJ, et al. Structure of influenza hemagglutinin in complex with an inhibitor of membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17736-17741.)

One of the most dynamic areas of virology concerns the identification of virus receptors on host cells. This interest stems in part from the critical importance of the attachment step as a determinant of target cell selection by many viruses. Several virus receptors have now been identified ( Table 134-2 ), and three important principles have emerged from studies of these receptors. First, viruses have adapted to use cell surface molecules designed to facilitate a variety of normal cellular functions. Virus receptors may be highly specialized proteins with limited tissue distribution, such as complement receptors, growth factor receptors, or neurotransmitter receptors, or more ubiquitous components of cellular membranes, such as integrins and other intercellular adhesion molecules, glycosaminoglycans, or sialic acid–containing oligosaccharides. Second, many viruses use more than a single receptor to mediate multistep attachment and internalization. For example, adenovirus binds coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) 43 and the integrins α v β 3 or α v β 5 44 ; herpes simplex virus (HSV) binds heparan sulfate 45 , 46 , 47 and herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM/HveA), 48 nectin 1 (PRR1/HveC), 49 or nectin 2 (PRR2/HveB) 50 ; HIV binds CD4 51 , 52 and chemokine receptors CXCR4 53 , 54 or CCR5 55 , 56 , 57 ; and reovirus binds sialylated glycans 58 , 59 and JAM-A. 60 , 61 Third, in many cases, receptor expression is not the sole determinant of viral tropism for particular cells and tissues in the host. Therefore, although receptor binding is the first step in the interaction between virus and cell, subsequent events in the viral replication cycle must also be supported for productive viral infection to occur.

TABLE 134-2.

Receptors and Entry Mediators Used by Selected Human Viruses

Several viruses bind receptors expressed at regions of cell-cell contact. 62 Junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A), which serves as a receptor for reovirus 60 and feline calicivirus, 63 and CAR, which serves as a receptor for some coxsackieviruses and adenoviruses, 43 are expressed at tight junctions 64 , 65 and adherens junctions. 66 , 67 Junctional regions are sites of enhanced membrane recycling, endocytic uptake, and intracellular signaling. 68 Therefore, it is possible that viruses have selected junction-associated proteins as receptors to usurp the physiologic functions of these molecules. In this regard, interactions of coxsackievirus with decay-accelerating factor elicit a tyrosine kinase–based signaling cascade that mediates subsequent interactions of the virus with CAR in tight junctions. 69 Structures of viral proteins or whole viral particles in complex with sialic acid have been determined for some viruses, including the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) 36 , 70 (see Fig. 134-3 ), polyomavirus, 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 foot-and-mouth disease virus, 75 reovirus attachment protein σ1, 58 , 59 and the VP8 domain of rotavirus capsid protein VP4. 34 Sialic acid binding in each of these cases occurs in a shallow groove at the surface of the viral protein. However, the architectures of the binding sites differ. Structures of complexes of viral proteins or viral particles and cell surface protein receptors have also been determined. These include adenovirus fiber knob and CAR, 76 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) gp42 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II protein, 77 HSV glycoprotein D and HVEM/HveA, 78 HIV gp120 and CD4, 38 measles virus HA and CD46 79 and SLAM (signaling lymphocyte-activation molecule), 80 reovirus σ1 and JAM-A, 61 and rhinovirus and ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1). 81 In several of these cases, the viral attachment proteins engage precisely the same domains used by their cognate receptors to bind natural ligands.

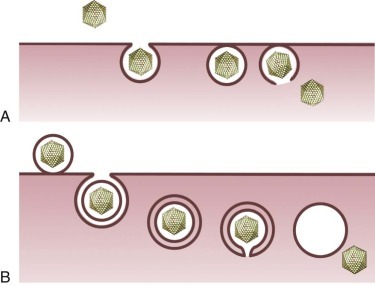

Penetration and Disassembly

Once attachment has occurred, the virus must penetrate the cell membrane, and the capsid must undergo a series of disassembly steps (uncoating) that prepare the virus for the next phases in viral replication. Enveloped viruses such as the paramyxoviruses and retroviruses enter cells by fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane ( Fig. 134-4 ). Attachment of these viruses to the cell surface induces changes in viral envelope proteins required for membrane fusion. For example, the binding of CD4 and certain chemokine receptors by HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 induces a series of conformational changes in gp120 that lead to the exposure of transmembrane protein gp41. 82 , 83 Fusion of viral and cellular membranes proceeds through subsequent interactions of the hydrophobic gp41 fusion peptide with the cell membrane. 84 , 85 , 86 , 87

FIGURE 134-4.

Mechanisms of viral entry into cells.

Nonenveloped (A) and enveloped (B) virus internalization by receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Other viruses enter cells by some form of receptor-mediated endocytic uptake (see Fig. 134-4 ). For several viruses, virus–receptor complexes induce formation of clathrin-coated pits that invaginate from the cell membrane to form coated vesicles. 88 These vesicles are rapidly uncoated and fuse with early endosomes, which sort internalized proteins for recycling to the cell surface or other cellular compartments, such as late endosomes or lysosomes. For other viruses, virus–receptor complexes are taken into cells by caveolae in lipid rafts. 88 Enveloped viruses such as dengue virus, 89 influenza virus, 90 and Semliki Forest virus 91 exploit the acidic environment of the endocytic compartment to induce conformational changes in surface glycoproteins required for membrane fusion. High-resolution structures of the influenza virus HA at acidic pH illustrate a dramatic conformational alteration leading to the fusion-active state (see Fig. 134-3 ). 90

Endocytic uptake and acidification are also required for entry of some nonenveloped viruses such as adenovirus, 92 , 93 parvovirus, 94 and reovirus. 95 , 96 In these cases, acidic pH may facilitate disassembly of the viral capsid to enable subsequent penetration of endosomal membranes. In addition to acidic pH, endocytic cathepsin proteases are required for disassembly of several viruses, including Ebola virus, 97 Hendra virus, 98 reovirus, 99 and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. 100

In contrast to enveloped viruses, nonenveloped viruses cross cell membranes using mechanisms that do not involve membrane fusion. This group of viruses includes several human pathogens, with adenoviruses, picornaviruses, and rotaviruses serving as prominent examples. Despite differences in genome and capsid composition, each of these viruses must penetrate cell membranes to deliver the genetic payload to the interior of the cell. Capsid rearrangements triggered by receptor binding, 101 , 102 acidic pH, 92 , 93 or proteolysis 103 , 104 serve essential functions in membrane penetration by some nonenveloped viruses. Although a precise understanding of the biochemical mechanisms that underlie viral membrane penetration is incomplete, small capsid proteins of several nonenveloped viruses, such as adenovirus, 105 poliovirus, 106 and reovirus, 107 are required for membrane penetration, perhaps by forming pores in host cell membranes.

Genome Replication

Once a virus has entered a target cell, it must replicate its genome and proteins. Replication strategies used by single-stranded RNA-containing viruses depend on whether the genome can be used as messenger (m)RNA. Translation-competent genomes, which include those of the coronaviruses, flaviviruses, picornaviruses, and togaviruses, are termed plus (+) sense and are translated by cellular ribosomes immediately following entry of the genome into the cytoplasm. For most viruses containing (+) sense RNA genomes, translation results in the synthesis of a large polyprotein that is cleaved into several smaller proteins through the action of viral and sometimes host proteases. One of these proteins is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which replicates the viral RNA. Genome replication of (+) sense RNA-containing viruses requires synthesis of a minus (–) sense RNA intermediate, which serves as template for production of (+) sense genomic RNA.

A different strategy is used by viruses containing (−) sense RNA genomes. The genomes of these viruses, which include the filoviruses, orthomyxoviruses, paramyxoviruses, and rhabdoviruses, cannot serve directly as mRNA. Therefore, viral particles must contain a co-packaged RdRp to transcribe (+) sense mRNAs using the (−) sense genomic RNA as template. Genome replication of (−) sense RNA-containing viruses requires synthesis of a (+) sense RNA intermediate, which serves as a template for production of (−) sense genomic RNA. Mechanisms that determine whether (+) sense RNAs are used as templates for translation or genome replication are not well understood.

RNA-containing viruses belonging to the family Reoviridae have segmented double-stranded (ds) RNA genomes. The innermost protein shell of these viruses (termed a single-shelled particle or core ) contains an RdRp that catalyzes the synthesis of (+) sense mRNA using as a template the (−) sense strand of each dsRNA segment. The mRNAs of these viruses are capped at their 5′-termini by virus-encoded enzymes and then extruded into the cytoplasm through channels in the single-shelled particle. 108 The (+) sense mRNAs also serve as a template for replication of dsRNA gene segments. Viral genome replication is thus completely conservative; neither strand of parental dsRNA is present in newly formed genomic segments.

The retroviruses are RNA-containing viruses that replicate using a DNA intermediate. The viral genomic RNA is (+) sense and single stranded; however, it does not serve as mRNA following viral entry. Instead, the retrovirus RNA genome is a template for synthesis of a double-stranded DNA copy, termed the provirus. Synthesis of the provirus is mediated by a virus-encoded RNA-dependent DNA polymerase or reverse transcriptase, so named because of the reversal of genetic information from RNA to DNA. The provirus translocates to the nucleus and integrates into host DNA. Expression of this integrated DNA is regulated for the most part by cellular transcriptional machinery. However, the human retroviruses HIV and human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV) encode proteins that augment transcription of viral genes. Intracellular signaling pathways are capable of activating retroviral gene expression and play important roles in inducing high levels of viral replication in response to certain stimuli. 109 Transcription of the provirus yields mRNAs that encode viral proteins and genome-length RNAs that are packaged into progeny virions. Such a replication strategy results in persistent infection in the host because the viral genome is maintained in the host cell genome and replicated with each cell division.

With the exception of the poxviruses, viruses containing DNA genomes replicate in the nucleus and for the most part use cellular enzymes for transcription and replication of their genomes. Transcription of most DNA-containing viruses is tightly regulated and results in the synthesis of early and late mRNA transcripts. The early transcripts encode regulatory proteins and proteins required for DNA replication, whereas the late transcripts encode structural proteins. Several DNA-containing viruses, such as adenovirus and human papillomavirus (HPV), induce cells to express host proteins required for viral DNA replication by stimulating cell-cycle progression. For example, the HPV E7 protein binds the retinoblastoma gene product pRB and liberates transcription factor E2F, which induces the cell cycle. 110 , 111 To prevent programmed cell death in response to E7-mediated unscheduled cell cycle progression, the HPV E6 protein mediates the ubiquitylation and degradation of tumor suppressor protein p53. 112 , 113 , 114

Some DNA-containing viruses, such as the herpesviruses, can establish latent infections in the host. Unlike the retroviruses, genomes of the herpesviruses do not integrate into host chromosomes but instead exist as plasmid-like episomes. Mechanisms that govern establishment of latency and subsequent reactivation of replication are not well understood. However, microRNAs encoded by cytomegalovirus (CMV) and perhaps other herpesviruses may promote persistence by targeting viral and cellular mRNAs that control viral gene expression and replication and innate immune responses to viral infection. 115 , 116

A fascinating aspect of virus–cell interactions is the replication microenvironments established in infected cells. Viral replication is a sophisticated interplay of transcription, translation, nucleic acid amplification, and particle assembly. Furthermore, infection must proceed under sensitive pathogen surveillance systems trained on virus-associated molecular patterns (e.g., unmethylated CpG dinucleotides in DNA viral genomes) and replicative intermediates (e.g., dsRNA generated during RNA virus replication) that may impose impassable blocks to infection. 117 Partitioning of the viral replication machinery from the surrounding intracellular milieu satisfies a spatial requirement to concentrate viral proteins and nucleic acid for efficient genome amplification and encapsidation while simultaneously shielding viral products from cellular sensors that provoke antiviral innate immune responses. Hence, as a rule, viral replication is a localized process, occurring within morphologically discrete cytoplasmic or nuclear structures variously termed viral inclusions (or inclusion bodies ), virosomes, viral factories, or viroplasm. These entities are novel, metabolically active organelles formed by contributions from both virus and cell. Many highly recognizable features of viral cytopathic effect observed using light microscopy, such as dense nuclear inclusions or refractile cytoplasmic densities, represent locally concentrated regions of viral nucleic acid and protein.

Membrane-associated replicase complexes appropriated by (+) sense RNA viruses are perhaps the most conspicuous examples of compartmentalized viral replication. In cells infected by these viruses, intracellular membranes originating from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; e.g., picornaviruses 118 , 119 ), ER-Golgi intermediate compartment and trans -Golgi network (e.g., flaviviruses 120 ), endolysosomal vesicles (e.g., alphaviruses 121 ), and autophagic vacuoles (e.g., poliovirus 122 ) are reduplicated and reorganized by viral proteins into platforms that anchor viral replication complexes consisting of the RdRp and other RNA-modifying enzymes necessary for RNA synthesis. Curiously, dsRNA viruses are thought to generate nonmembranous intracytoplasmic replication factories, even though their life cycles pass through a (+) polarity RNA intermediate. However, in an interesting functional parallel with (+) sense RNA viruses, the assembly pathway of rotavirus, a dsRNA virus, involves budding of immature particles into the ER, where a lipid envelope is transiently acquired and subsequently replaced by the outermost protein shell. 123 Perhaps additional roles for cellular membranes in non–membrane-bound viral replication complexes await discovery.

The tight relationship of RNA virus replication to cellular membranes is less predictable for DNA viruses. For example, in distinction to the supporting role of autophagy in the replication of some RNA viruses, autophagosomes (stress-induced, double-membraned vesicles that remove noxious cytoplasmic materials to lysosomes for degradation) defend against infection by HSV-1, which encodes a protein that inhibits induction of autophagy and accentuates viral virulence. 124 , 125 The replication and assembly complexes of many DNA viruses, including adenoviruses, herpesviruses, papillomaviruses, polyomaviruses, and parvoviruses, are associated with promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies, 126 , 127 which have been ascribed functions in diverse nuclear processes encompassing gene regulation, tumor suppression, apoptosis, and removal of aggregated or foreign proteins. 128 It appears that DNA viruses exploit PML bodies in a variety of ways, which include consolidation and disposal of misfolded viral proteins, sequestration of host-cell stress response factors that block infection, and segregation of interfering cellular DNA repair proteins from sites of viral replication. 129

The life cycles of all viruses that replicate in eukaryotic cells are physically and functionally intertwined with the cytoskeleton. Many viruses with nuclear replication programs, such as adenovirus, HSV, and influenza virus, are transported by motor proteins along microtubules toward the nucleus, resulting ultimately in release of the viral genome into the nucleoplasm through nuclear pores. 130 The microtubule network is also conscripted as an egress pathway by a number of enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV, HSV, vaccinia virus) for conveyance of immature particles to cytolemmal sites of virion budding. 131 Furthermore, microtubules and actin filaments may serve as anchorage points for nucleoprotein complexes that coordinate genome expression or replication with cytoplasmic replication programs, exemplified by parainfluenza virus (PIV), 132 reovirus, 133 and vaccinia virus. 134 Because the cytoskeleton is a decentralized organelle linking cellular structural elements to the metabolic and transport machineries, it is not surprising that viruses capitalize on this highly integrative system, which provides a stable platform for replication and enables purposeful movement of virions or subviral components within cells to facilitate the requisite partitioning of viral assembly and disassembly.

Cell Killing

Viral infection can compromise numerous cellular processes, such as nucleic acid and protein synthesis, maintenance of cytoskeletal architecture, and preservation of membrane integrity. 135 Many viruses are also capable of inducing the genetically programmed mechanism of cell death that leads to apoptosis of host cells. 136 , 137 Apoptotic cell death is characterized by cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, condensation of nuclear chromatin, and activation of an endogenous endonuclease, which results in cleavage of cellular DNA into oligonucleosome-length DNA fragments. 138 These changes occur according to predetermined developmental programs or in response to certain environmental stimuli. In some cases, apoptosis may serve as an antiviral defense mechanism to limit viral replication by destruction of virus-infected cells or reduction of potentially harmful inflammatory responses elicited by viral infection. 139 In other cases, apoptosis may result from viral induction of cellular factors required for efficient viral replication. 136 , 137 Generally, RNA-containing viruses, including influenza virus, measles virus, poliovirus, reovirus, and Sindbis virus, induce apoptosis of host cells, whereas DNA-containing viruses, including adenovirus, CMV, EBV, HPV, and the poxviruses, encode proteins that block apoptosis. For some viruses, the duration of the viral infectious cycle may determine whether apoptosis is induced or inhibited. Viruses capable of completing an infectious cycle before induction of apoptosis would not require a means to inhibit this cellular response to viral infection. Interestingly, several viruses that cause encephalitis are capable of inducing apoptosis of infected neurons ( Fig. 134-5 ). 140 , 141 , 142

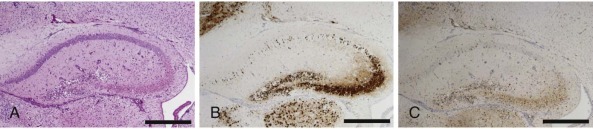

FIGURE 134-5.

Reovirus-induced apoptosis in the murine central nervous system.

Consecutive sections of the hippocampus prepared from a newborn mouse 10 days following intracranial inoculation with reovirus strain type 3 Dearing. Cells were stained with (A) hematoxylin and eosin, (B) reovirus antigen, and (C) the activated form of apoptosis protease caspase-3. Cells that stain positive for reovirus antigen or activated caspase 3 contain a dark precipitate in the cytoplasm, including neuronal processes. Scale bars, 100 µm.

(Modified from Danthi P, Coffey CM, Parker JS, et al. Independent regulation of reovirus membrane penetration and apoptosis by the µ 1 Φ domain. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000248.)

Antiviral Drugs

(Also see Chapters 43 to 47Chapter 43Chapter 44Chapter 45Chapter 46Chapter 47.)

Knowledge of viral replication strategies has provided insights into critical steps in the viral life cycle that can serve as potential targets for antiviral therapy. For example, drugs can be designed to interfere with virus binding to target cells or prevent penetration and disassembly once receptor engagement has occurred. Steps involved in the replication of the viral genome are also obvious targets for antiviral therapy. A number of antiviral agents inhibit viral polymerases, including those active against herpesviruses (e.g., acyclovir), HIV (e.g., zidovudine), and HBV (e.g., entecavir). Drugs that inhibit viral proteases have been developed; several are used to treat HCV 143 , 144 and HIV 145 infection. These drugs block the proteolytic processing of viral precursor polyproteins and serve as potent inhibitors of replication. Other viral enzymes also serve as targets for antiviral therapy. The influenza virus neuraminidase is required for the release of progeny influenza virus particles from infected cells. Oseltamivir and zanamivir bind the neuraminidase catalytic site and efficiently inhibit the enzyme. 146 These drugs have been used in the prophylaxis and treatment of influenza virus infection. 147

Better understanding of viral replication strategies and mechanisms of virus-induced cell killing is paving the way for the rational design of novel antiviral therapeutics. One of the most exciting approaches to the development of antiviral agents is the use of high-resolution x-ray crystallography and molecular modeling to optimize interactions between these inhibitory molecules and their target viral proteins. Such structure-based drug design has led to the development of synthetic peptides (e.g., enfuvirtide) that inhibit HIV entry by blocking gp41-mediated membrane fusion. 148 Other vulnerable steps in HIV replication are targets of drugs approved for patient treatment, including entry inhibitors that interfere with gp120 binding to CCR5 149 and agents that prevent proviral integration into cellular DNA through inhibition of viral integrase activity 150 (see Chapter 130). Several inhibitors of the HCV protease and polymerase are also in clinical development 151 (see Chapter 46).

Despite promising advances in rational antiviral drug design, current therapeutic approaches to some viral infections rely heavily on compounds with less specific mechanisms of action. One such agent, interferon (IFN)-α, efficiently inhibits a broad spectrum of viruses and is secreted by diverse cell types as part of the host innate immune response. Recombinant IFN-α is presently used to treat HBV and HCV infections. Ribavirin, a synthetic guanosine analogue, inhibits the replication of many RNA- and DNA-containing viruses through complex mechanisms involving inhibition of viral RNA synthesis and disturbances in intracellular pools of guanosine triphosphate. 152 , 153 This drug is routinely used to treat HCV infection and sometimes administered in aerosolized form to treat respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) lower respiratory tract infection in hospitalized children and in severely ill and immunocompromised patients. Ribavirin therapy reduces the mortality associated with certain viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as that caused by Lassa virus. 154 Broader-spectrum therapies exemplified by IFN-α and ribavirin remain part of the first-line defense against emerging pathogens and other susceptible viruses for which biochemical and structural information is insufficient to design high-potency agent-specific drugs.

Virus–Host Interaction

One of the most formidable challenges in virology is to apply knowledge gained from studies of virus–cell interactions in tissue culture systems to an understanding of how viruses interact with host organisms to cause disease. Virus–host interactions are often described in terms of pathogenesis and virulence. Pathogenesis is the process whereby a virus interacts with its host in a discrete series of stages to produce disease ( Table 134-3 ). Virulence is the capacity of a virus to produce disease in a susceptible host. Virulence is often measured in terms of the quantity of virus required to cause illness or death in a predefined fraction of experimental animals infected with the virus. Virulence is dependent on viral and host factors and must be measured using carefully defined conditions (e.g., virus strain, dose, and route of inoculation; host species, age, and immune status). In many cases, it has been possible to identify roles played by individual viral and host proteins at specific stages in viral pathogenesis and to define the importance of these proteins in viral virulence.

TABLE 134-3.

Stages in Virus–Host Interaction

The first step in the process of virus–host interaction is the exposure of a susceptible host to viable virus under conditions that promote infection ( Fig. 134-6 ). Infectious virus may be present in respiratory droplets or aerosols, in fecally contaminated food or water, or in a body fluid or tissue (e.g., blood, saliva, urine, semen, or a transplanted organ) to which the susceptible host is exposed. In some cases, the virus is inoculated directly into the host through the bite of an animal vector or through the use of a contaminated needle. Infection can also be transmitted from mother to infant through virus that has infected the placenta or birth canal or by virus in breast milk. In some cases, acute viral infections result from the reactivation of endogenous latent virus (e.g., reactivation of HSV giving rise to herpes labialis) rather than de novo exposure to exogenous virus.

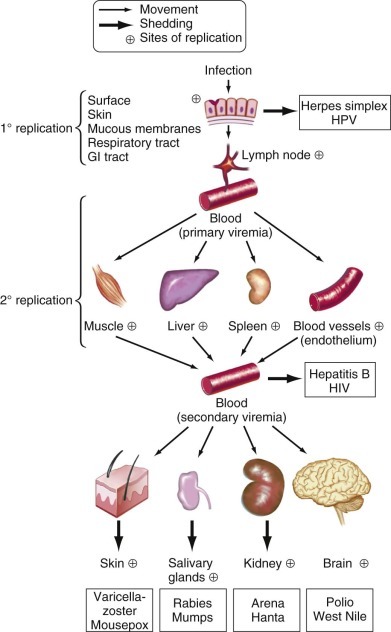

FIGURE 134-6.

Entry and spread of viruses in human hosts.

Some major steps in viral spread and invasion of target organs are shown. Neural spread is not illustrated. GI, gastrointestinal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus.

(Modified from Nathanson N, Tyler KL. Entry, dissemination, shedding, and transmission of viruses. In: Nathanson N, ed. Viral Pathogenesis. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:13-33.)

Exposure of respiratory mucosa to virus by direct inoculation or inhalation is an important route of viral entry into the host. A simple cough can generate up to 10,000 small, potentially infectious aerosol particles, and a sneeze can produce nearly 2 million. The distribution of these particles depends on a variety of environmental factors, the most important of which are temperature, humidity, and air currents. In addition to these factors, particle size is an important determinant of particle distribution. In general, smaller particles remain airborne longer than larger ones. Particle size also contributes to particle fate after inhalation. Larger particles (>6 µm) are generally trapped in the nasal turbinates, whereas smaller particles may ultimately travel to the alveolar spaces of the lower respiratory tract.

Fecal-oral transmission represents an additional important route of viral entry into the host. Food, water, or hands contaminated by infected fecal material can facilitate the entry of a virus via the mouth into the gastrointestinal tract, the environment of which requires viruses that infect by this route to have certain physical properties. Viruses capable of enteric transmission must be acid stable and resistant to bile salts. Because conditions in the stomach and intestine are destructive to lipids contained in viral envelopes, most viruses that spread by the fecal-oral route are nonenveloped. Interestingly, many viruses that enter the host via the gastrointestinal tract require proteolysis of certain capsid components to infect intestinal cells productively. Treatment of mice with inhibitors of intestinal proteases blocks infection by reovirus 155 and rotavirus, 156 which demonstrates the critical importance of proteolysis in the initiation of enteric infection by these viruses. The host microbiota is essential for infection by some viruses. 157 , 158

To produce systemic disease, a virus must cross the mucosal barrier that separates the luminal compartments of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts from the host's parenchymal tissues. Studies with reovirus illustrate one strategy used by viruses to cross mucosal surfaces to invade the host after entry into the gastrointestinal tract. 159 , 160 After oral inoculation of mice, reovirus adheres to the surface of intestinal microfold cells (M cells) that overlie collections of intestinal lymphoid tissue (Peyer's patches). In electron micrographs, reovirus virions can be followed sequentially as they are transported within vesicles from the luminal to the subluminal surface of M cells. Virions subsequently appear within Peyer's patches and then spread to regional lymph nodes and extraintestinal lymphoid organs such as the spleen. A similar pathway of spread has been described for poliovirus 161 and HIV, 162 suggesting that M cells represent an important portal for viral invasion of the host after entry into the gastrointestinal tract.

Once a virus has entered the host, it can replicate locally or spread from the site of entry to distant organs to produce systemic disease (see Fig. 134-6 ). Classic examples of localized infections in which viral entry and replication occur at the same anatomic site include respiratory infections caused by influenza virus, RSV, and rhinovirus; enteric infections produced by norovirus and rotavirus; and dermatologic infections caused by HPV (warts) and paravaccinia virus (milker's nodules). Other viruses spread to distant sites in the host after primary replication at sites of entry. For example, poliovirus spreads from the gastrointestinal tract to the central nervous system (CNS) to produce meningitis, encephalitis, or poliomyelitis. Measles virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) enter the host through the respiratory tract and then spread to lymph nodes, skin, and viscera. Pathobiologic definitions of viruses based on spread potential have begun to blur amid accumulating evidence that model agents of localized infection may disseminate to distant sites. For example, rotavirus, an important cause of pediatric acute gastroenteritis, replicates vigorously in villous tip epithelial cells of the small intestine but is also frequently associated with viral antigen and RNA in blood, the clinical significance of which is unclear. 163 Influenza virus is another case in point; viral RNA in blood is detected at a substantial frequency in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and correlates with more severe disease and increased mortality. 164

Release of some viruses occurs preferentially from the apical or basolateral surface of polarized cells, such as epithelial cells. In the case of enveloped viruses, polarized release is frequently determined by preferential sorting of envelope glycoproteins to sites of viral budding. Specific amino-acid sequences in these viral proteins direct their transport to a particular aspect of the cell surface. 165 , 166 Polarized release of virus at apical surfaces may facilitate local spread of infection, whereas release at basolateral surfaces may facilitate systemic invasion by providing virus access to subepithelial lymphoid, neural, or vascular tissues.

Many viruses use the bloodstream to spread in the host from sites of primary replication to distant target tissues (see Fig. 134-6 ). In some cases, viruses may enter the bloodstream directly, such as during a blood transfusion or via an arthropod bite. More commonly, viruses enter the bloodstream after replication at some primary site. Important sites of primary replication preceding hematogenous spread of viruses include Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes for enteric viruses, bronchoalveolar cells for respiratory viruses, and subcutaneous tissue and skeletal muscle for alphaviruses and flaviviruses. In the case of reovirus, infection of endothelial cells leads to hematogenous dissemination in the host. 167 , 168

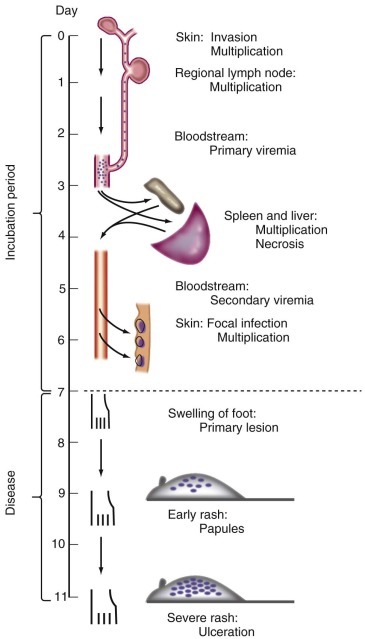

Pioneering studies by Fenner with mousepox (ectromelia) virus suggest that an initial low-titer viremia (primary viremia) serves to seed virus to a variety of intermediate organs, where a period of further replication leads to a high-titer viremia (secondary viremia) that disseminates virus to the ultimate target organs ( Fig. 134-7 ). 169 It is often difficult to identify primary and secondary viremias in naturally occurring viral infections. However, replication of many viruses in reticuloendothelial organs (e.g., liver, spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow), muscle, fat, and even vascular endothelial cells can play an important role in maintaining viremia. 168

FIGURE 134-7.

Pathogenesis of mousepox virus infection.

Successive waves of viremia are shown to seed the spleen and liver and then the skin.

(From Fenner F. Mousepox [infectious ectromelia of mice]: a review. J Immunol. 1949;63:341-373.)

Viruses that reach the bloodstream may travel free in plasma (e.g., enteroviruses and togaviruses) or in association with specific blood cells. 170 A number of viruses are spread hematogenously by macrophages (e.g., CMV, HIV, measles virus) or lymphocytes (e.g., CMV, EBV, HIV, HTLV, measles virus). Although many viruses have the capacity to agglutinate erythrocytes in vitro (a process called hemagglutination), only in exceptional cases (e.g., Colorado tick fever virus) are erythrocytes used to transport virus in the bloodstream.

The maintenance of viremia depends on the interplay among factors that promote virus production and those that favor viral clearance. A number of variables that affect the efficiency of virus removal from plasma have been identified. In general, the larger the viral particle, the more efficiently it is cleared. Viruses that induce high titers of neutralizing antibodies are more efficiently cleared than those that do not induce humoral immune responses. Finally, phagocytosis of virus by cells in the host reticuloendothelial system can contribute to viral clearance.

A major pathway used by viruses to spread from sites of primary replication to the nervous system is through nerves. Numerous diverse viruses, including Borna disease virus, coronavirus, HSV, poliovirus, rabies virus, reovirus, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEE), are capable of neural spread. Several of these viruses accumulate at the neuromuscular junction after primary replication in skeletal muscle. 171 , 172 HSV appears to enter nerve cells via receptors that are located primarily at synaptic endings rather than on the nerve cell body. 173 Spread to the CNS by HSV, 174 rabies virus, 171 , 172 and reovirus 175 , 176 can be interrupted by scission of the appropriate nerves or by chemical agents that inhibit axonal transport. Neural spread of some of these viruses occurs by the microtubule-based system of fast axonal transport. 177

Viruses are not limited to a single route of spread. VZV, for example, enters the host by the respiratory route and then spreads from respiratory epithelium to the reticuloendothelial system and skin via the bloodstream. Infection of the skin produces the characteristic exanthem of chickenpox. The virus subsequently enters distal terminals of sensory neurons and travels to dorsal root ganglia, where it establishes latent infection. Reactivation of VZV from latency results in transport of the virus in sensory nerves to skin, where it gives rise to vesicular lesions in a dermatomal distribution characteristic of zoster or shingles .

Poliovirus is also capable of spreading by hematogenous and neural routes. Poliovirus is generally thought to spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the CNS via the bloodstream, although it has been suggested that the virus may spread via autonomic nerves in the intestine to the brainstem and spinal cord. 178 , 179 This hypothesis is supported by experiments using transgenic mice expressing the human poliovirus receptor. 180 When these mice are inoculated with poliovirus intramuscularly in the hind limb, virus does not reach the CNS if the sciatic nerve ipsilateral to the site of inoculation is transected. 181 Once poliovirus reaches the CNS, axonal transport is the major route of viral dissemination. Similar mechanisms of spread may be used by other enteroviruses.

The capability of a virus to infect a distinct group of cells in the host is referred to as tropism. For many viruses, tropism is determined by the availability of virus receptors on the surface of a host cell. This concept was first appreciated in studies of poliovirus when it was recognized that the capacity of the virus to infect specific tissues paralleled its capacity to bind homogenates of the susceptible tissues in vitro. 182 The importance of receptor expression as a determinant of poliovirus tropism was conclusively demonstrated by showing that cells not susceptible for poliovirus replication could be made susceptible by recombinant expression of the poliovirus receptor. 183 In addition to the availability of virus receptors, tropism can also be determined by postattachment steps in viral replication, such as the regulation of viral gene expression. For example, some viruses contain genetic elements, termed enhancers, that act to stimulate transcription of viral genes. 184 , 185 Some enhancers are active in virtually all types of cells, whereas others show exquisite tissue specificity. The promoter-enhancer region of John Cunningham (JC) polyomavirus is active in cultured human glial cells but not in HeLa cervical epithelial cells. 186 Cell-specific expression of the JC virus genome correlates well with the capacity of this virus in immunocompromised persons to produce progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a disease in which JC virus infection is limited to oligodendroglia in the CNS.

Specific steps in virus–host interaction, such as the route of entry and pathway of spread, also can strongly influence viral tropism. For example, encephalitis viruses such as VEE are transmitted to humans by insect bites. These viruses undergo local primary replication and then spread to the CNS by hematogenous and neural routes. 187 After oral inoculation, VEE is incapable of primary replication and spread to the CNS, illustrating that tropism can be determined by the site of entry into the host. Influenza virus buds exclusively from the apical surface of respiratory epithelial cells, 188 which may limit its capacity to spread within the host and infect cells at distant sites.

A wide variety of host factors can influence viral tropism. These include age, nutritional status, and immune responsiveness, as well as certain genetic polymorphisms that affect susceptibility to viral infection. Age-related susceptibility to infection is observed for many viruses, including reovirus, 189 , 190 RSV, 191 , 192 , 193 and rotavirus. 194 , 195 The increased susceptibility in young children to these viruses may in part be due to immaturity of the immune response but also may be related to intrinsic age-specific factors that enhance host susceptibility to infection. Nutritional status is a critical determinant of the tropism and virulence of many viruses. For example, persons with vitamin A deficiency have enhanced susceptibility to measles virus infection. 196 , 197 Similarly, the outcome of most viral infections is strongly linked to the immune competence of the host.

The genetic basis of host susceptibility to viral infections is complex. Studies with inbred strains of mice indicate that genetic variation can alter susceptibility to viral disease by a variety of mechanisms. 198 These can involve differences in immune responses, variability in the ability to produce antiviral mediators such as IFN, and differential expression of functional virus receptors. Polymorphisms in the expression of chemokine receptor CCR5, which serves as a co-receptor for HIV, 55 , 56 , 57 are associated with alterations in susceptibility to HIV infection. 199 , 200

Persistent Infections

Many viruses are capable of establishing persistent infections, of which two types are recognized: chronic and latent. Chronic viral infections are characterized by continuous shedding of virus for prolonged periods of time. Congenital infections with rubella virus and CMV and persistent infections with HBV and HCV are examples of chronic viral infections. Latent viral infections are characterized by maintenance of the viral genome in host cells in the absence of viral replication. Herpesviruses and retroviruses can establish latent infections. The distinction between chronic and latent infections is not readily apparent for some viruses, such as HIV, which can establish both chronic and latent infections in the host. 201 , 202 , 203 Viruses capable of establishing persistent infections must have a means of evading the host immune response and a mechanism of attenuating their virulence. Lentiviruses such as equine infectious anemia virus 204 and HIV 205 , 206 , 207 are capable of extensive antigenic variation resulting in escape from neutralizing antibody responses by the host.

Several viruses encode proteins that directly attenuate the host immune response (e.g., the adenovirus E3/19K protein 208 and CMV US11 gene product 209 block cell surface expression of MHC class I proteins, resulting in diminished presentation of viral antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes [CTLs]). The poxviruses encode a variety of immunomodulatory molecules including CrmA, which blocks T-cell–mediated apoptosis of virus-infected cells. 210 In some cases (e.g., the CNS), preferential sites for persistent viral infections are not readily accessible by the immune system, 211 which may favor establishment of persistence.

Viruses and Cancer

Several viruses produce disease by promoting malignant transformation of host cells. Work by Peyton Rous with an avian retrovirus was the first to demonstrate that viral infections can cause cancer. 212 Rous sarcoma virus encodes an oncogene, v -src, which is a homologue of a cellular proto-oncogene, c -src. 213 , 214 Cells infected with Rous sarcoma virus become transformed. 215 , 216 , 217 , 218 , 219 Several viruses are associated with malignancies in humans. EBV is associated with many neoplasms, including Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease, large B-cell lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. HBV and HCV are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPV is associated with cervical cancer and a variety of anogenital and esophageal neoplasms. Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus is associated with Kaposi sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma in persons with HIV infection.

Often, the linkage of a virus to a particular neoplasm can be attributed to transforming properties of the virus itself. For example, EBV encodes several latency-associated proteins that are responsible for immortalization of B cells; these proteins likely play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of EBV-associated malignancies. 220 Similarly, HPV encodes the E6 and E7 proteins that block apoptosis 112 , 113 , 114 and induce cell cycle progression, 110 , 111 respectively. It is hypothesized that unregulated expression of these proteins induced by the aberrant integration of the HPV genome into host DNA is responsible for malignant transformation. 221 The tumorigenicity of polyomaviruses, which are oncogenic in rodent species, is mediated by a family of viral proteins known as tumor (T) antigens. Reminiscent of the HPV E6 and E7 proteins, T antigens induce cell cycling and block the ensuing cellular apoptotic response to unscheduled cell division. 222 The normally episomal polyomavirus genome becomes integrated into cellular DNA during neoplastic transformation of nonpermissive cells unable to support the entire viral replication program, which would otherwise culminate in cell death. Discovery of a human polyomavirus clonally integrated into cells of an aggressive form of skin cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma, 2 substantiates the long-standing suspicion that polyomaviruses can also promote neoplasia in humans.

In other cases, mechanisms of malignancy triggered by viral infection are less clear. HCV is an RNA-containing virus that lacks reverse transcriptase and a means of viral genome integration. However, chronic infection with HCV is strongly associated with hepatocellular cancer. 223 It is possible that increased cell turnover and inflammatory mediators elicited by chronic HCV infection increase the risk of genetic damage, which results in malignant transformation. Some HCV proteins may also play a contributory role in neoplasia. For example, the HCV core protein can protect cells against apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). 224

Viral Virulence Determinants

Viral surface proteins involved in attachment and entry influence the virulence of diverse groups of viruses. For example, polymorphisms in the attachment proteins of influenza virus, 225 , 226 polyomavirus, 227 reovirus, 228 rotavirus, 229 and VEE 230 are strongly linked to virulence and can be accurately termed virulence determinants. Viral attachment proteins can serve this function by altering the affinity of virus–receptor interactions or modulating the kinetics of viral disassembly. Importantly, sequences in viral genomes that do not encode protein can also influence viral virulence. Mutations that contribute to the attenuated virulence of the Sabin strains of poliovirus are located in the 5′ nontranslated region of the viral genome. 231 These mutations attenuate poliovirus virulence by altering the efficiency of viral protein synthesis.

A number of viruses encode proteins that enhance virulence by modulation of host immune responses. Illustrative examples include the influenza A NS1 protein, which interferes with activation of cellular innate immune responses to viral infection, 232 and translation products of the adenovirus E3 transcriptional unit, which serve to prevent cytotoxic T-cell recognition of virally infected cells and block immunologically activated signaling pathways that lead to infected-cell death. 208 , 233 In many cases, these proteins are dispensable for viral replication in cultured cells. In this way, immunomodulatory viral virulence determinants resemble classic bacterial virulence factors such as various types of secreted toxins.

Host Responses to Infection

The immune response to viral infection involves complex interactions among leukocytes, nonhematopoietic cells, signaling proteins, soluble proinflammatory mediators, antigen-presenting molecules, and antibodies. These cells and molecules collaborate in a highly regulated fashion to limit viral replication and dissemination through recognition of broadly conserved molecular signatures, followed by virus-specific adaptive responses that further control infection and establish antigen-selective immunologic memory. The innate antiviral response is a local, transient, antigen-independent perimeter defense strategically focused at the site of virus incursion into an organ or tissue. Mediated by ancient families of membrane-associated and cytosolic molecules known as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), the innate immune system detects pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are fundamental structural components of microbial products including nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids. 234 Viral PAMPs in the form of single-stranded (ss)RNA, dsRNA, and DNA evoke the innate immune response through two groups of PRRs: the transmembrane Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the cytosolic nucleic acid sensors. The latter include retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors, nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich-repeat containing proteins (NLRs) such as NLRP, and DNA sensors. 235 Nucleic acid binding by PRRs activates signaling pathways leading to the production and extracellular release of IFN-α, IFN-β, and proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18. IFN-α and IFN-β engage the cell surface IFN-α/β receptor and thereby mediate expression of hundreds of gene products that corporately suppress viral replication and establish an intracellular antiviral state in neighboring uninfected cells. Well-described IFN-inducible gene products include the latent enzymes dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) and 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), both of which are activated by dsRNA. 236 PKR inhibits the initiation of protein synthesis through phosphorylation of translation initiation factor eIF2α. The 2′,5′-oligoandenylates generated by OAS bind and activate endoribonuclease RNAse L, which degrades viral mRNA. In addition to mediating an intracellular antiviral state, IFN-α/β also stimulates the antigen-independent destruction of virus-infected cells by a specialized population of lymphocytes known as natural killer (NK) cells. 237 Importantly, IFNs bridge innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses through multiple modes of action, which include enhancing viral antigen presentation by class I MHC proteins, 238 promoting the proliferation of MHC class I–restricted CD8 + CTLs, 239 and facilitating the functional maturation of dendritic cells. 240 Proinflammatory mediators IL-1β and IL-18 pleiotropically stimulate and amplify the innate immune response through induction of other inflammatory mediators, immune cell activation, and migration of inflammatory cells into sites of infection. 241 These molecules perform essential functions in host antiviral defense. 242

The adaptive immune response confers systemic and enduring pathogen-selective immunity through expansion and functional differentiation of viral antigen-specific T and B lymphocytes. Having both regulatory and effector roles, T lymphocytes are centrally positioned in the scheme of adaptive immunity. The primary cell type involved in the resolution of acute viral infection is the CD8 + CTL, which induces lethal proapoptotic signaling in virus-infected cells upon recognition of endogenously produced viral protein fragments presented by cell surface MHC class I molecules. Less frequently, CD4 + T cells, which recognize MHC class II–associated viral oligopeptides processed from exogenously acquired proteins, also demonstrate cytotoxicity against viral antigen-presenting cells. 243 The usual function of CD4 + T lymphocytes is to orchestrate and balance cell-mediated (CTL) and humoral (B lymphocyte) responses to infection. Classes of CD4 + helper T-cell subsets—Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg (regulatory T), and Tfh (follicular helper T)—have been defined based on characteristic patterns of cytokine secretion and effector activities. 244 , 245 Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes are usually associated with the development of cell-mediated and humoral responses, respectively, to viral infection. Th17 and Treg CD4 + subsets are important for control of immune responses and prevention of autoimmunity, but their precise roles in viral disease and antiviral immunity are not clear. For certain persistent viral infections, such as those caused by HIV and HSV, Treg cells might exacerbate disease through suppression of CTLs or, paradoxically, ameliorate illness by attenuating immune-mediated cell and tissue injury. 246 Tfh cells promote differentiation of antigen-specific memory B lymphocytes and plasma cells within germinal centers. 247 Therefore, Tfh cells likely occupy a central place in the humoral response to viral infection and vaccination. Although Tfh cell functions are not unique to antiviral responses, chronic viral infections including HBV and HIV appear to stimulate proliferation of these cells. 248 , 249 The Tfh phenotype may interconvert with other T-helper lineage profiles and thus represent a differentiation intermediate rather than a unique CD4 + T lymphocyte subset. 245

The primacy of cell-mediated immune responses in combating viral infections is revealed by the extreme vulnerability of individuals to chronic and life-threatening viral diseases when cellular immunity is dysfunctional. Those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) exemplify the catastrophic consequences of collapsing cell-mediated immunity; progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy caused by JC polyomavirus, along with severe mucocutaneous and disseminated CMV, HSV, and VZV infections, are frequent complications of vanishing CD4 + T cells. Similarly, iatrogenic cellular immunodeficiency associated with hematopoietic stem cell and solid-organ transplantation or antineoplastic treatment regimens predisposes to severe, potentially fatal infections with herpesviruses and respiratory viral pathogens such as adenovirus, PIV, and RSV, 250 all of which normally produce self-limited illness in immunocompetent hosts. Prevention and management of serious viral respiratory infections are significant challenges in myelosuppression units because of the communicability of respiratory viruses and paucity of effective drugs to combat these ubiquitous agents. Individuals with significantly impaired cell-mediated immunity are also at increased risk for enhanced viral replication and systemic disease following immunization with live, attenuated viral vaccines (e.g., measles-mumps-rubella [MMR] and VZV vaccines). Hence, live viral vaccines are generally contraindicated for immunocompromised persons (see Chapter 321). TNF-α inhibitor therapy, increasingly employed to manage a variety of rheumatologic and inflammatory diseases, enhances the risk of HBV reactivation with potentially life-threatening consequences. 251 Preventive and interventional HBV treatment strategies are necessary to circumvent complications of uncontrolled viral replication in these patients.

In contrast to cell-mediated immune mechanisms, humoral responses are usually not a determinative factor in the resolution of primary viral infections. (One notable exception is a syndrome of chronic enteroviral meningitis in the setting of agammaglobulinemia. 252 ) However, for most human viral pathogens, the presence of antibody is associated with protection against initial infection in vaccinees or reinfection in hosts with a history of natural infection. 253 Longitudinal studies indicate that levels of protective serum antibodies (induced by natural infection or immunization) to common viruses, including EBV, measles, mumps, and rubella, are remarkably stable, with calculated antibody half-lives ranging from several decades to thousands of years. 254 The protective role of antibodies on secondary exposure is frequently explained as interruption of viremic spread where a hematogenous phase is involved, such as occurs with measles, mumps, and rubella viruses, poliovirus, VZV, and most arboviruses. Nevertheless, most human viruses, excluding insect-transmitted agents, enter their hosts by transgression of a mucosal barrier, frequently undergoing primary replication in mucosal epithelium or adjacent lymphoid tissues. Neutralizing IgA exuded onto mucosal epithelial surfaces may protect against primary infection at this portal of viral entry. A classic example is gut mucosal immunity induced by orally administered Sabin poliovirus vaccine containing live-attenuated virus. Secretory IgA against poliovirus blocks infection at the site of primary replication and consequently interrupts the chain of viral transmission, although fully virulent revertant viruses arise at regular frequency in vaccine recipients, who may develop disease and also transmit revertant strains to nonimmune individuals. 255 Clinical and experimental studies of immunity to HIV have led to the recognition that resident immune responses at exposed mucosal surfaces are likely critical components of host resistance to primary HIV infection, and achievement of potent mucosal immunity has emerged as an important consideration for the design of candidate HIV vaccines. 256 Despite the appearance of serum neutralizing antibodies to HIV several weeks after infection, viral eradication is thwarted by selection of neutralization-resistant variant strains from a mutant pool, which is perpetually replenished because of extreme plasticity within neutralization determinants on the viral envelope glycoproteins. 257 Identification of epitopes bound by broadly neutralizing antiviral antibodies has provided potential new targets for structure-based vaccine design. 258

Protection against viral infection by serum immunoglobulins is often correlated with antibody-mediated neutralization of viral infectivity in cultured cells. Antibodies interrupt the viral life cycle at early steps, which may include cross-linking virion particles into noninfectious aggregates, steric hindrance of receptor engagement, and interference with viral disassembly. 259 It is presumed that virus neutralization in cell culture by human serum is reflective of antibody activity in the intact host, but the mechanistic basis of infection blockade and disease prevention by antibodies in vivo is difficult to define precisely. For example, exclusively in vivo functions of the humoral antiviral response include Fc-mediated virion phagocytosis 260 , 261 and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). ADCC responses require effectors from both the innate and adaptive systems, NK cells and antibodies, respectively. 262 The basis of ADCC is FcγRIIIa receptor-dependent recognition by NK cells of virus-specific IgG bound to antigens expressed on the surface of infected cells, leading to release of perforin and granzymes from NK cells that eventuate in target cell apoptosis. Neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages also possess Fc receptors and may participate in ADCC.

Key References

The complete reference list is available online at Expert Consult.

- 2. Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Epperson S, Brammer L, Blanton L. Update: influenza activity—United States and worldwide, May 20-September 22, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:777–781. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Zhang X, Settembre E, Xu C. Near-atomic resolution using electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle reconstruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1867–1872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711623105. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Liljeroos L, Huiskonen JT, Ora A. Electron cryotomography of measles virus reveals how matrix protein coats the ribonucleocapsid within intact virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18085–18090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105770108. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Chappell JD, Prota A, Dermody TS. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 reveals evolutionary relationship to adenovirus fiber. EMBO J. 2002;21:1–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Weis W, Brown JH, Cusack S. Structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with its receptor, sialic acid. Nature. 1988;333:426–431. doi: 10.1038/333426a0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Hogle JM, Chow M, Filman DJ. Three dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 Å resolution. Science. 1985;229:1358–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.2994218. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Haywood AM. Virus receptors: binding, adhesion strengthening, and changes in viral structure. J Virol. 1994;68:1–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.1-5.1994. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Reiter DM, Frierson JM, Halvorson EE. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 in complex with sialylated oligosaccharides. PLoS Path. 2011;7:e1002166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002166. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Spear PG. Viral interactions with receptors in cell junctions and effects on junctional stability. Dev Cell. 2002;3:462–464. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00298-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Kolatkar PR, Bella J, Olson NH. Structural studies of two rhinovirus serotypes complexed with fragments of their cellular receptor. EMBO J. 1999;18:6249–6259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6249. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Mercer J, Schelhaas M, Helenius A. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:803–833. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-104626. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 90. Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]