Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

1. americans’ views on whether, and in what circumstances, abortion should be legal.

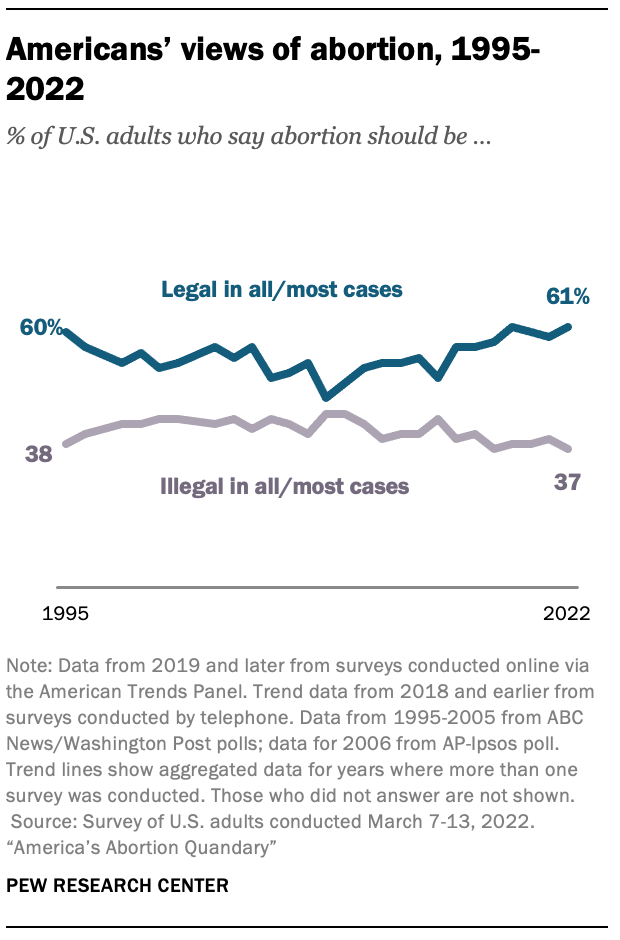

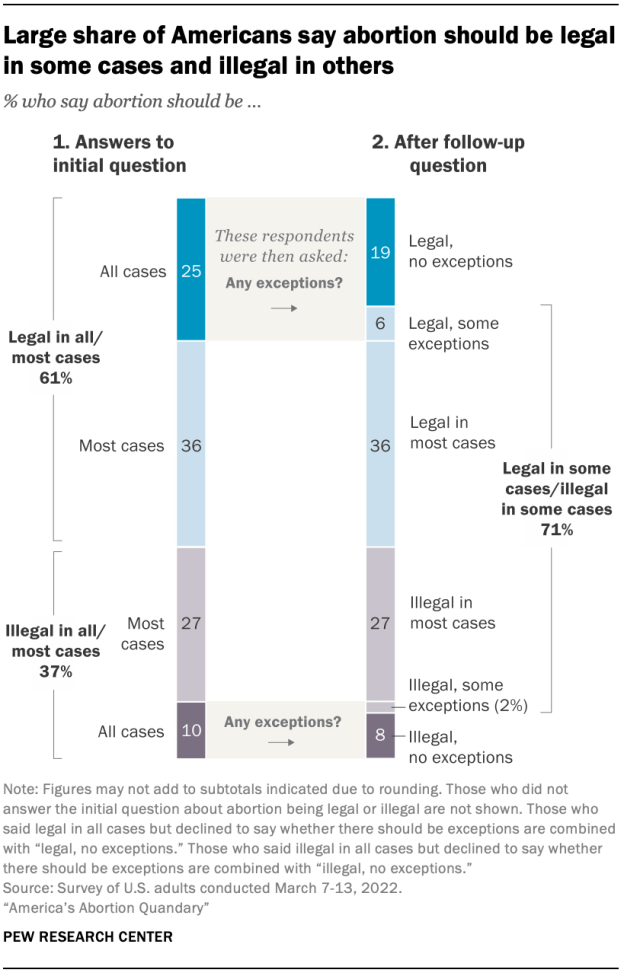

As the long-running debate over abortion reaches another key moment at the Supreme Court and in state legislatures across the country , a majority of U.S. adults continue to say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. About six-in-ten Americans (61%) say abortion should be legal in “all” or “most” cases, while 37% think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. These views have changed little over the past several years: In 2019, for example, 61% of adults said abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Most respondents in the new survey took one of the middle options when first asked about their views on abortion, saying either that abortion should be legal in most cases (36%) or illegal in most cases (27%).

Respondents who said abortion should either be legal in all cases or illegal in all cases received a follow-up question asking whether there should be any exceptions to such laws. Overall, 25% of adults initially said abortion should be legal in all cases, but about a quarter of this group (6% of all U.S. adults) went on to say that there should be some exceptions when abortion should be against the law.

One-in-ten adults initially answered that abortion should be illegal in all cases, but about one-in-five of these respondents (2% of all U.S. adults) followed up by saying that there are some exceptions when abortion should be permitted.

Altogether, seven-in-ten Americans say abortion should be legal in some cases and illegal in others, including 42% who say abortion should be generally legal, but with some exceptions, and 29% who say it should be generally illegal, except in certain cases. Much smaller shares take absolutist views when it comes to the legality of abortion in the U.S., maintaining that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions (19%) or illegal in all circumstances (8%).

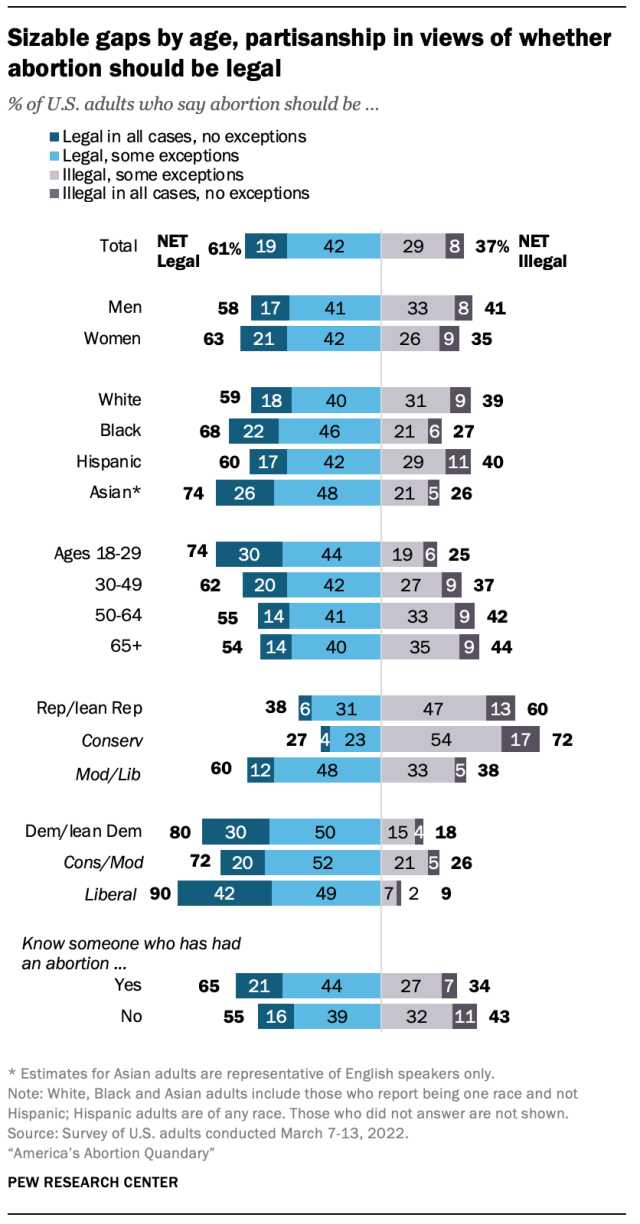

There is a modest gender gap in views of whether abortion should be legal, with women slightly more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all cases or in all cases but with some exceptions (63% vs. 58%).

Younger adults are considerably more likely than older adults to say abortion should be legal: Three-quarters of adults under 30 (74%) say abortion should be generally legal, including 30% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception.

But there is an even larger gap in views toward abortion by partisanship: 80% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, compared with 38% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Previous Center research has shown this gap widening over the past 15 years.

Still, while partisans diverge in views of whether abortion should mostly be legal or illegal, most Democrats and Republicans do not view abortion in absolutist terms. Just 13% of Republicans say abortion should be against the law in all cases without exception; 47% say it should be illegal with some exceptions. And while three-in-ten Democrats say abortion should be permitted in all circumstances, half say it should mostly be legal – but with some exceptions.

There also are sizable divisions within both partisan coalitions by ideology. For instance, while a majority of moderate and liberal Republicans say abortion should mostly be legal (60%), just 27% of conservative Republicans say the same. Among Democrats, self-described liberals are twice as apt as moderates and conservatives to say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception (42% vs. 20%).

Regardless of partisan affiliation, adults who say they personally know someone who has had an abortion – such as a friend, relative or themselves – are more likely to say abortion should be legal than those who say they do not know anyone who had an abortion.

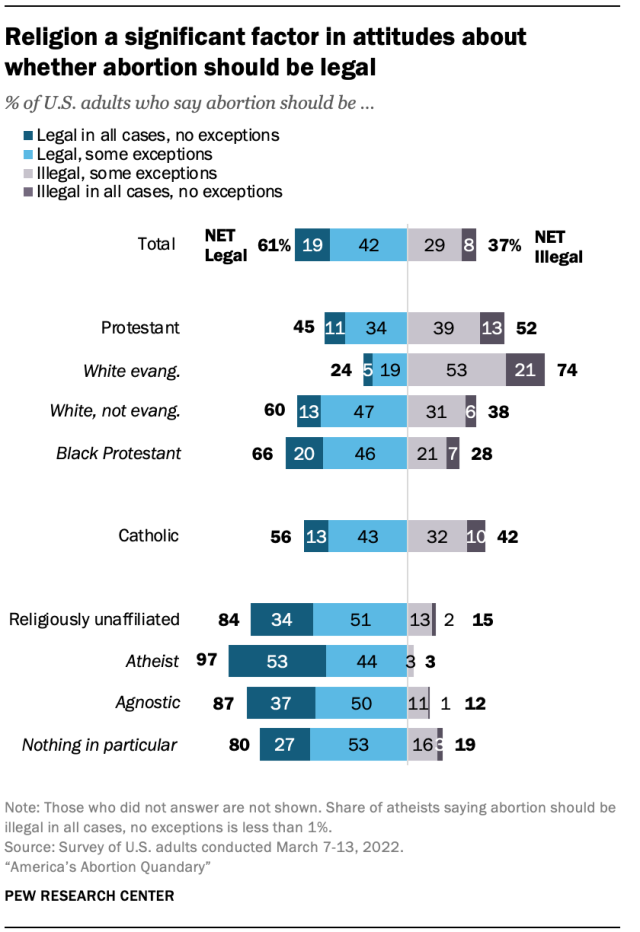

Views toward abortion also vary considerably by religious affiliation – specifically among large Christian subgroups and religiously unaffiliated Americans.

For example, roughly three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. This is far higher than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (38%) or Black Protestants (28%) who say the same.

Despite Catholic teaching on abortion , a slim majority of U.S. Catholics (56%) say abortion should be legal. This includes 13% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception, and 43% who say it should be legal, but with some exceptions.

Compared with Christians, religiously unaffiliated adults are far more likely to say abortion should be legal overall – and significantly more inclined to say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Within this group, atheists stand out: 97% say abortion should be legal, including 53% who say it should be legal in all cases without exception. Agnostics and those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” also overwhelmingly say that abortion should be legal, but they are more likely than atheists to say there are some circumstances when abortion should be against the law.

Although the survey was conducted among Americans of many religious backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, it did not obtain enough respondents from non-Christian groups to report separately on their responses.

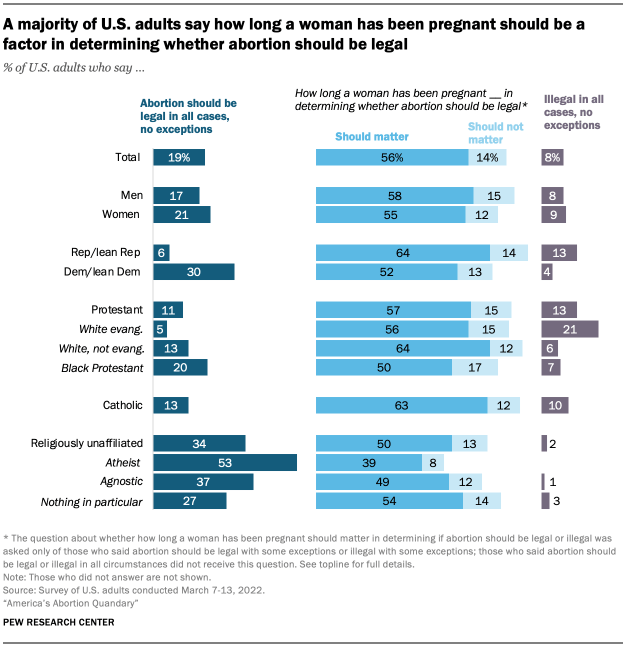

Abortion at various stages of pregnancy

As a growing number of states debate legislation to restrict abortion – often after a certain stage of pregnancy – Americans express complex views about when abortion should generally be legal and when it should be against the law. Overall, a majority of adults (56%) say that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining when abortion should be legal, while far fewer (14%) say that this should not be a factor. An additional one-quarter of the public says that abortion should either be legal (19%) or illegal (8%) in all circumstances without exception; these respondents did not receive this question.

Among men and women, Republicans and Democrats, and Christians and religious “nones” who do not take absolutist positions about abortion on either side of the debate, the prevailing view is that the stage of the pregnancy should be a factor in determining whether abortion should be legal.

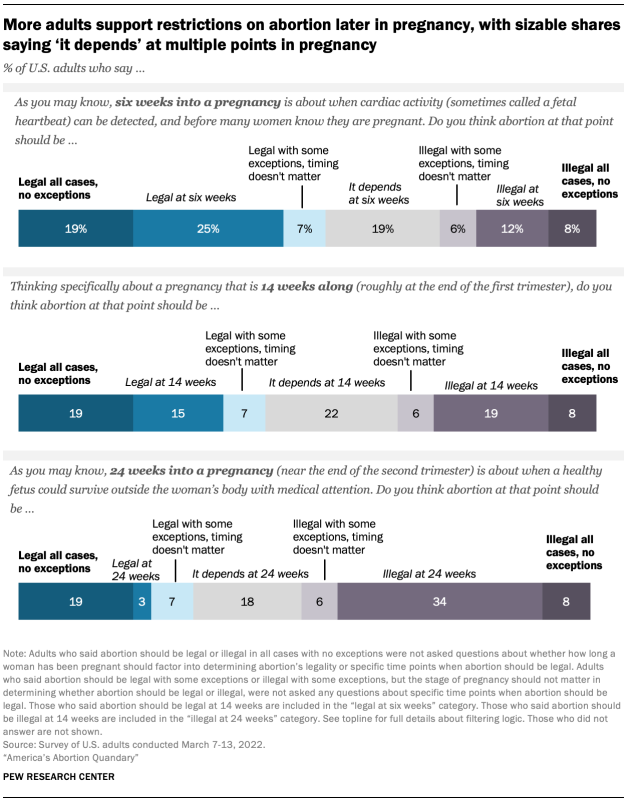

Americans broadly are more likely to favor restrictions on abortion later in pregnancy than earlier in pregnancy. Many adults also say the legality of abortion depends on other factors at every stage of pregnancy.

One-in-five Americans (21%) say abortion should be illegal at six weeks. This includes 8% of adults who say abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception as well as 12% of adults who say that abortion should be illegal at this point. Additionally, 6% say abortion should be illegal in most cases and how long a woman has been pregnant should not matter in determining abortion’s legality. Nearly one-in-five respondents, when asked whether abortion should be legal six weeks into a pregnancy, say “it depends.”

Americans are more divided about what should be permitted 14 weeks into a pregnancy – roughly at the end of the first trimester – although still, more people say abortion should be legal at this stage (34%) than illegal (27%), and about one-in-five say “it depends.”

Fewer adults say abortion should be legal 24 weeks into a pregnancy – about when a healthy fetus could survive outside the womb with medical care. At this stage, 22% of adults say abortion should be legal, while nearly twice as many (43%) say it should be illegal . Again, about one-in-five adults (18%) say whether abortion should be legal at 24 weeks depends on other factors.

Respondents who said that abortion should be illegal 24 weeks into a pregnancy or that “it depends” were asked a follow-up question about whether abortion at that point should be legal if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Most who received this question say abortion in these circumstances should be legal (54%) or that it depends on other factors (40%). Just 4% of this group maintained that abortion should be illegal in this case.

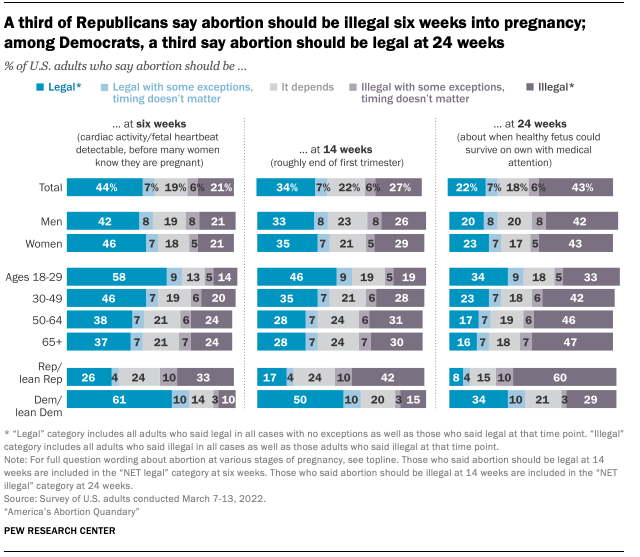

This pattern in views of abortion – whereby more favor greater restrictions on abortion as a pregnancy progresses – is evident across a variety of demographic and political groups.

Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that abortion should be legal at each of the three stages of pregnancy asked about on the survey. For example, while 26% of Republicans say abortion should be legal at six weeks of pregnancy, more than twice as many Democrats say the same (61%). Similarly, while about a third of Democrats say abortion should be legal at 24 weeks of pregnancy, just 8% of Republicans say the same.

However, neither Republicans nor Democrats uniformly express absolutist views about abortion throughout a pregnancy. Republicans are divided on abortion at six weeks: Roughly a quarter say it should be legal (26%), while a similar share say it depends (24%). A third say it should be illegal.

Democrats are divided about whether abortion should be legal or illegal at 24 weeks, with 34% saying it should be legal, 29% saying it should be illegal, and 21% saying it depends.

There also is considerable division among each partisan group by ideology. At six weeks of pregnancy, just one-in-five conservative Republicans (19%) say that abortion should be legal; moderate and liberal Republicans are twice as likely as their conservative counterparts to say this (39%).

At the same time, about half of liberal Democrats (48%) say abortion at 24 weeks should be legal, while 17% say it should be illegal. Among conservative and moderate Democrats, the pattern is reversed: A plurality (39%) say abortion at this stage should be illegal, while 24% say it should be legal.

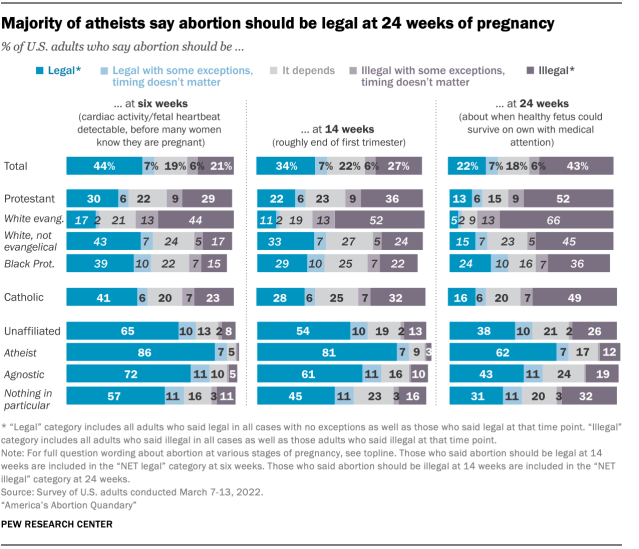

Christian adults are far less likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say abortion should be legal at each stage of pregnancy.

Among Protestants, White evangelicals stand out for their opposition to abortion. At six weeks of pregnancy, for example, 44% say abortion should be illegal, compared with 17% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 15% of Black Protestants. This pattern also is evident at 14 and 24 weeks of pregnancy, when half or more of White evangelicals say abortion should be illegal.

At six weeks, a plurality of Catholics (41%) say abortion should be legal, while smaller shares say it depends or it should be illegal. But by 24 weeks, about half of Catholics (49%) say abortion should be illegal.

Among adults who are religiously unaffiliated, atheists stand out for their views. They are the only group in which a sizable majority says abortion should be legal at each point in a pregnancy. Even at 24 weeks, 62% of self-described atheists say abortion should be legal, compared with smaller shares of agnostics (43%) and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” (31%).

As is the case with adults overall, most religiously affiliated and religiously unaffiliated adults who originally say that abortion should be illegal or “it depends” at 24 weeks go on to say either it should be legal or it depends if the pregnant woman’s life is in danger or the baby would be born with severe disabilities. Few (4% and 5%, respectively) say abortion should be illegal at 24 weeks in these situations.

Abortion and circumstances of pregnancy

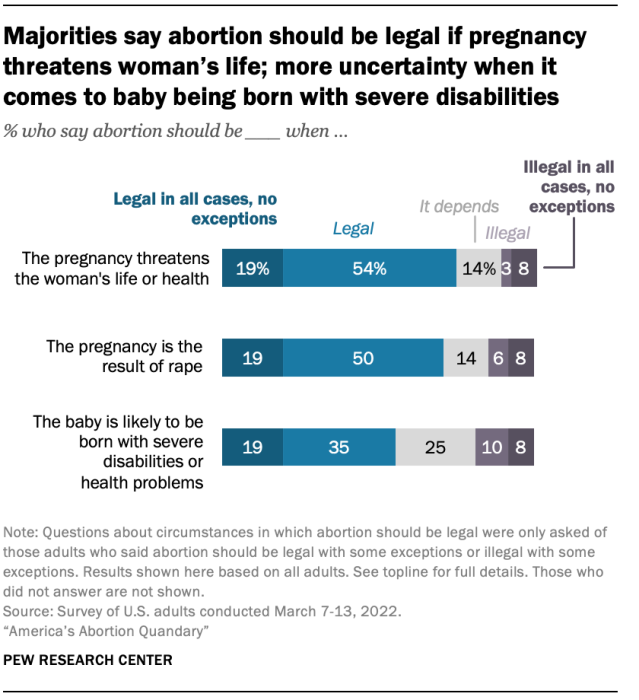

The stage of the pregnancy is not the only factor that shapes people’s views of when abortion should be legal. Sizable majorities of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal if the pregnancy threatens the life or health of the pregnant woman (73%) or if pregnancy is the result of rape (69%).

There is less consensus when it comes to circumstances in which a baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems: 53% of Americans overall say abortion should be legal in such circumstances, including 19% who say abortion should be legal in all cases and 35% who say there are some situations where abortions should be illegal, but that it should be legal in this specific type of case. A quarter of adults say “it depends” in this situation, and about one-in-five say it should be illegal (10% who say illegal in this specific circumstance and 8% who say illegal in all circumstances).

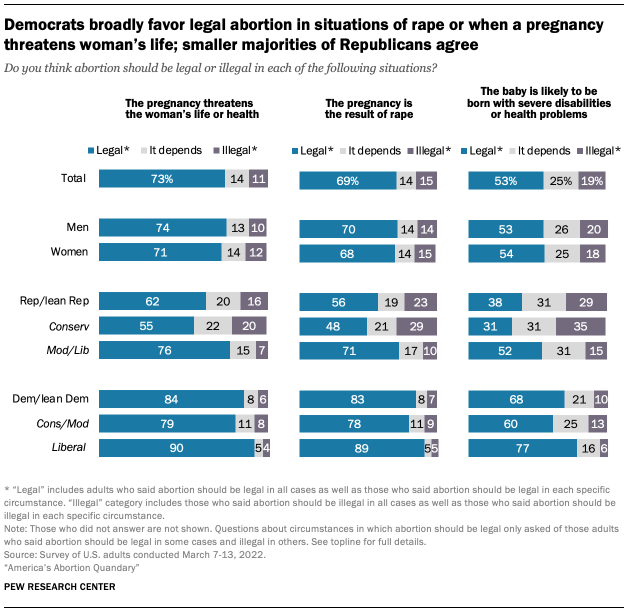

There are sizable divides between and among partisans when it comes to views of abortion in these situations. Overall, Republicans are less likely than Democrats to say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances outlined in the survey. However, both partisan groups are less likely to say abortion should be legal when the baby may be born with severe disabilities or health problems than when the woman’s life is in danger or the pregnancy is the result of rape.

Just as there are wide gaps among Republicans by ideology on whether how long a woman has been pregnant should be a factor in determining abortion’s legality, there are large gaps when it comes to circumstances in which abortions should be legal. For example, while a clear majority of moderate and liberal Republicans (71%) say abortion should be permitted when the pregnancy is the result of rape, conservative Republicans are more divided. About half (48%) say it should be legal in this situation, while 29% say it should be illegal and 21% say it depends.

The ideological gaps among Democrats are slightly less pronounced. Most Democrats say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances – just to varying degrees. While 77% of liberal Democrats say abortion should be legal if a baby will be born with severe disabilities or health problems, for example, a smaller majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (60%) say the same.

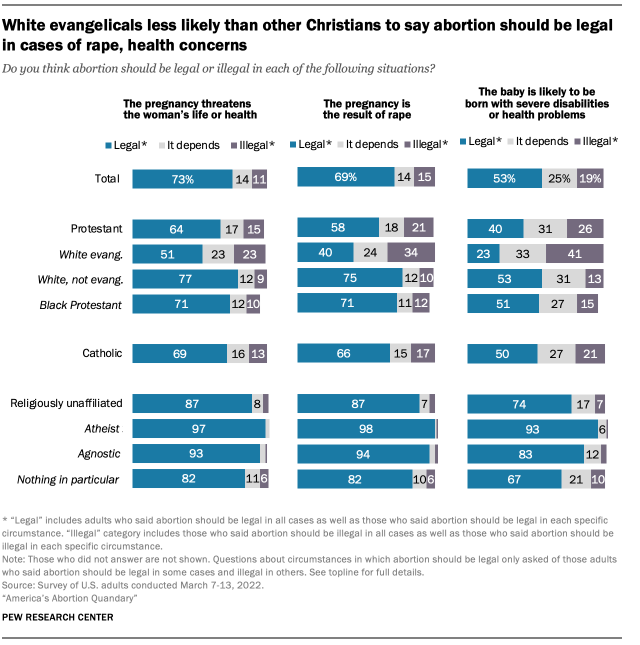

White evangelical Protestants again stand out for their views on abortion in various circumstances; they are far less likely than White non-evangelical or Black Protestants to say abortion should be legal across each of the three circumstances described in the survey.

While about half of White evangelical Protestants (51%) say abortion should be legal if a pregnancy threatens the woman’s life or health, clear majorities of other Protestant groups and Catholics say this should be the case. The same pattern holds in views of whether abortion should be legal if the pregnancy is the result of rape. Most White non-evangelical Protestants (75%), Black Protestants (71%) and Catholics (66%) say abortion should be permitted in this instance, while White evangelicals are more divided: 40% say it should be legal, while 34% say it should be illegal and about a quarter say it depends.

Mirroring the pattern seen among adults overall, opinions are more varied about a situation where a baby might be born with severe disabilities or health issues. For instance, half of Catholics say abortion should be legal in such cases, while 21% say it should be illegal and 27% say it depends on the situation.

Most religiously unaffiliated adults – including overwhelming majorities of self-described atheists – say abortion should be legal in each of the three circumstances.

Parental notification for minors seeking abortion

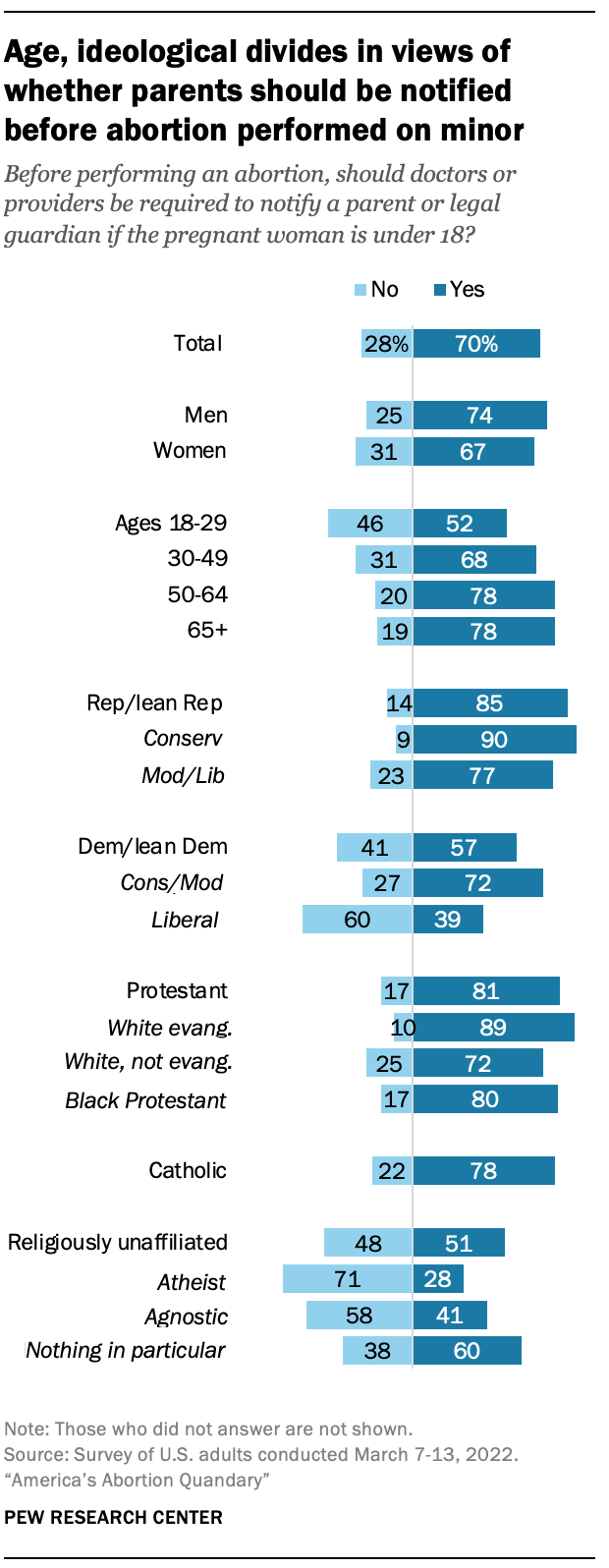

Seven-in-ten U.S. adults say that doctors or other health care providers should be required to notify a parent or legal guardian if the pregnant woman seeking an abortion is under 18, while 28% say they should not be required to do so.

Women are slightly less likely than men to say this should be a requirement (67% vs. 74%). And younger adults are far less likely than those who are older to say a parent or guardian should be notified before a doctor performs an abortion on a pregnant woman who is under 18. In fact, about half of adults ages 18 to 24 (53%) say a doctor should not be required to notify a parent. By contrast, 64% of adults ages 25 to 29 say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, as do 68% of adults ages 30 to 49 and 78% of those 50 and older.

A large majority of Republicans (85%) say that a doctor should be required to notify the parents of a minor before an abortion, though conservative Republicans are somewhat more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans to take this position (90% vs. 77%).

The ideological divide is even more pronounced among Democrats. Overall, a slim majority of Democrats (57%) say a parent should be notified in this circumstance, but while 72% of conservative and moderate Democrats hold this view, just 39% of liberal Democrats agree.

By and large, most Protestant (81%) and Catholic (78%) adults say doctors should be required to notify parents of minors before an abortion. But religiously unaffiliated Americans are more divided. Majorities of both atheists (71%) and agnostics (58%) say doctors should not be required to notify parents of minors seeking an abortion, while six-in-ten of those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” say such notification should be required.

Penalties for abortions performed illegally

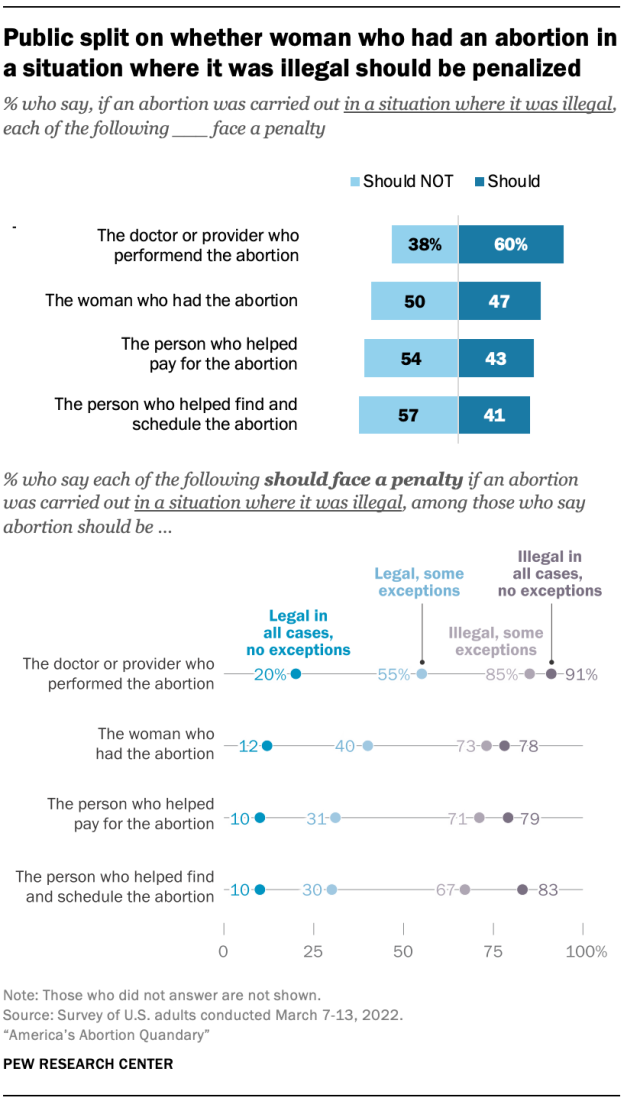

Americans are divided over who should be penalized – and what that penalty should be – in a situation where an abortion occurs illegally.

Overall, a 60% majority of adults say that if a doctor or provider performs an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, they should face a penalty. But there is less agreement when it comes to others who may have been involved in the procedure.

While about half of the public (47%) says a woman who has an illegal abortion should face a penalty, a nearly identical share (50%) says she should not. And adults are more likely to say people who help find and schedule or pay for an abortion in a situation where it is illegal should not face a penalty than they are to say they should.

Views about penalties are closely correlated with overall attitudes about whether abortion should be legal or illegal. For example, just 20% of adults who say abortion should be legal in all cases without exception think doctors or providers should face a penalty if an abortion were carried out in a situation where it was illegal. This compares with 91% of those who think abortion should be illegal in all cases without exceptions. Still, regardless of how they feel about whether abortion should be legal or not, Americans are more likely to say a doctor or provider should face a penalty compared with others involved in the procedure.

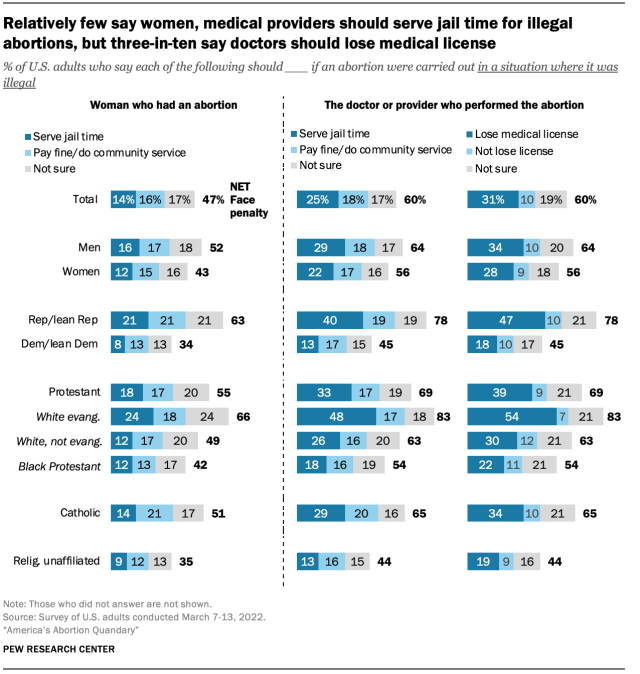

Among those who say medical providers and/or women should face penalties for illegal abortions, there is no consensus about whether they should get jail time or a less severe punishment. Among U.S. adults overall, 14% say women should serve jail time if they have an abortion in a situation where it is illegal, while 16% say they should receive a fine or community service and 17% say they are not sure what the penalty should be.

A somewhat larger share of Americans (25%) say doctors or other medical providers should face jail time for providing illegal abortion services, while 18% say they should face fines or community service and 17% are not sure. About three-in-ten U.S. adults (31%) say doctors should lose their medical license if they perform an abortion in a situation where it is illegal.

Men are more likely than women to favor penalties for the woman or doctor in situations where abortion is illegal. About half of men (52%) say women should face a penalty, while just 43% of women say the same. Similarly, about two-thirds of men (64%) say a doctor should face a penalty, while 56% of women agree.

Republicans are considerably more likely than Democrats to say both women and doctors should face penalties – including jail time. For example, 21% of Republicans say the woman who had the abortion should face jail time, and 40% say this about the doctor who performed the abortion. Among Democrats, far smaller shares say the woman (8%) or doctor (13%) should serve jail time.

White evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Protestant groups to favor penalties for abortions in situations where they are illegal. Fully 24% say the woman who had the abortion should serve time in jail, compared with just 12% of White non-evangelical Protestants or Black Protestants. And while about half of White evangelicals (48%) say doctors who perform illegal abortions should serve jail time, just 26% of White non-evangelical Protestants and 18% of Black Protestants share this view.

- Only respondents who said that abortion should be legal in some cases but not others and that how long a woman has been pregnant should matter in determining whether abortion should be legal received questions about abortion’s legality at specific points in the pregnancy. ↩

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, majority of public disapproves of supreme court’s decision to overturn roe v. wade, wide partisan gaps in abortion attitudes, but opinions in both parties are complicated, key facts about the abortion debate in america, about six-in-ten americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, fact sheet: public opinion on abortion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Jessica Winter

What can economic research tell us about the effect of abortion access on women’s lives?

Subscribe to the center for economic security and opportunity newsletter, caitlin knowles myers and caitlin knowles myers john g. mccullough professor of economics; co-director, middlebury initiative for data and digital methods - middlebury college @caitlin_k_myers morgan welch morgan welch senior research assistant & project coordinator - center on children and families, economic studies, brookings institution.

November 30, 2021

- 21 min read

On September 20, 2021, a group of 154 distinguished economists and researchers filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court of the United States in advance of the Mississippi case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization . For a full review of the evidence that shows how causal inference tools have been used to measure the effects of abortion access in the U.S., read the brief here .

Introduction

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization considers the constitutionality of a 2018 Mississippi law that prohibits women from accessing abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. This case is widely expected to determine the fate of Roe v. Wade as Mississippi is directly challenging the precedent set by the Supreme Court’s decisions in Roe , which protects abortion access before fetal viability (typically between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy). On December 1, 2021, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson . In asking the Court to overturn Roe , the state of Mississippi offers reassurances that “there is simply no causal link between the availability of abortion and the capacity of women to act in society” 1 and hence no reason to believe that abortion access has shaped “the ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation” 2 as the Court had previously held.

While the debate over abortion often centers on largely intractable subjective questions of ethics and morality, in this instance the Court is being asked to consider an objective question about the causal effects of abortion access on the lives of women and their families. The field of economics affords insights into these objective questions through the application of sophisticated methodological approaches that can be used to isolate and measure the causal effects of abortion access on reproductive, social, and economic outcomes for women and their families.

Separating Correlation from Causation: The “Credibility Revolution” in Economics

To measure the causal effect of abortion on women’s lives, one must differentiate its effects from those of other forces, such as economic opportunity, social mores, the availability of contraception. Powerful statistical methodologies in the causal inference toolbox have made it possible for economists to do just that, moving beyond the maxim “correlation isn’t necessarily causation” and applying the scientific method to figure out when it is.

This year’s decision by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee recognized the contributions 3 of economists David Card, Joshua Angrist, and Guido Imbens, awarding them the Nobel Prize for their pathbreaking work developing and applying the tools of causal inference in a movement dubbed “the credibility revolution” (Angrist and Pischke, 2010). The gold standard for establishing such credibility is a well-executed randomized controlled trial – an experiment conducted in the lab or field in which treatment is randomly assigned. When economists can feasibly and ethically implement such experiments, they do. However, in the social world, this opportunity is often not available. For instance, one cannot feasibly or ethically randomly assign abortion access to some individuals but not others. Faced with this obstacle, economists turn to “natural” or “quasi” experimental methods, ones in which they are able to credibly argue that treatment is as good as randomly assigned.

Related Content

Elaine Kamarck

October 5, 2021

Katherine Guyot, Isabel V. Sawhill

July 29, 2019

Pioneering applications of this approach include work by Angrist and Krueger (1991) leveraging variation in compulsory school attendance laws to measure the effects of schooling on earnings and work by Card and Krueger (1994) leveraging minimum wage variation across state borders to measure the effects of the minimum wages on employment outcomes. The use of these methods is now widespread, not just in economics, but in other social sciences as well. Fueled by advances in computing technology and the availability of data, quasi-experimental methodologies have become as ubiquitous as they are powerful, applied to answer questions ranging from the effects of economic shocks on civil conflict (Miguel, Sayanath, and Sergenti, 2004), to the effects of the Clean Water Act on water pollution levels (Keiser and Shapiro, 2019), and effects of access to food stamps in childhood on later life outcomes (Hoynes, Schanzenbach, Almond 2016; Bailey et al., 2020).

Research demonstrates that abortion access does, in fact, profoundly affect women’s lives by determining whether, when, and under what circumstances they become mothers.

Economists also have applied these tools to study the causal effects of abortion access. Research drawing on methods from the “credibility revolution” disentangles the effects of abortion policy from other societal and economic forces. This research demonstrates that abortion access does, in fact, profoundly affect women’s lives by determining whether, when, and under what circumstances they become mothers, outcomes which then reverberate through their lives, affecting marriage patterns, educational attainment, labor force participation, and earnings.

The Effects of Abortion Access on Women’s Reproductive, Economic, and Social Lives

Evidence of the effects of abortion legalization.

The history of abortion legalization in the United States affords both a canonical and salient example of a natural experiment. While Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in most of the country in 1973, five states—Alaska, California, Hawaii, New York, and Washington—and the District of Columbia repealed their abortion bans several years in advance of Roe . Using a methodology known as “difference-in-difference estimation,” researchers compared changes in outcomes in these “repeal states” when they lifted abortion bans to changes in outcomes in the rest of the country. They also compared changes in outcomes in the rest of the country in 1973 when Roe legalized abortion to changes in outcomes in the repeal states where abortion already was legal. This difference-in-differences methodology allows the states where abortion access is not changing to serve as a counterfactual or “control” group that accounts for other forces that were impacting fertility and women’s lives in the Roe era.

Among the first to employ this approach was a team of economists (Levine, Staiger, Kane, and Zimmerman, 1999) who estimated that the legalization of abortion in repeal states led to a 4% to 11% decline in births in those states relative to the rest of the country. Levine and his co-authors found that these fertility effects were particularly large for teens and women of color, who experienced birth rate reductions that were nearly three times greater than the overall population as a result of abortion legalization. Multiple research teams have replicated the essential finding that abortion legalization substantially impacted American fertility while extending the analysis to consider other outcomes. 4 For example, Myers (2017) found that abortion legalization reduced the number of women who became teen mothers by 34% and the number who became teen brides by 20%, and again observed effects that were even larger for Black teens. Farin, Hoehn-Velasco, and Pesko (2021) found that abortion legalization reduced maternal mortality among Black women by 30-40%, with little impact on white women, offering the explanation that where abortion was illegal, Black women were less likely to be able to access safe abortions by traveling to other states or countries or by obtaining a clandestine abortion from a trusted health care provider.

The ripple effects of abortion access on the lives of women and their families

This research, which clearly demonstrates the causal relationship between abortion access and first-order demographic and health outcomes, laid the foundation for researchers to measure further ripple effects through the lives of women and their families. Multiple teams of authors have extended the difference-in-differences research designs to study educational and labor market outcomes, finding that abortion legalization increased women’s education, labor force participation, occupational prestige, and earnings and that all these effects were particularly large for Black women (Angrist and Evans, 1996; Kalist, 2004; Lindo, Pineda-Torres, Pritchard, and Tajali, 2020; Jones, 2021).

Additionally, research shows that abortion access has not only had profound effects on women’s economic and social lives but has also impacted the circumstances into which children are born. Researchers using difference-in-differences research designs have found that abortion legalization reduced the number of children who were unwanted (Bitler and Zavodny, 2002a, reduced cases of child neglect and abuse (Bitler and Zavodny, 2002b; 2004), reduced the number of children who lived in poverty (Gruber, Levine, and Staiger, 1999), and improved long-run outcomes of an entire generation of children by increasing the likelihood of attending college and reducing the likelihood of living in poverty and receiving public assistance (Ananat, Gruber, Levine, and Staiger, 2009).

Access to abortion continues to be important to women’s lives

The research cited above relies on variation in abortion access from the 1970s, and much has changed in terms of both reproductive technologies and women’s lives. Recent research shows, however, that even with the social, economic, and legal shifts that have occurred over the last few decades and even with expanded access to contraception, abortion access remains relevant to women’s reproductive lives. Today, nearly half of pregnancies are unintended (Finer and Zolna, 2016). About 6% of young women (ages 15-34) experience an unintended pregnancy each year (Finer, Lindberg, and Desai, 2018), and about 1.4% of women of childbearing age obtain an abortion each year (Jones, Witwer, and Jerman, 2019). At these rates, approximately one in four women will receive an abortion in their reproductive lifetimes. The fact is clear: women continue to rely on abortion access to determine their reproductive lives.

But what about their economic and social lives? While women have made great progress in terms of their educational attainment, career trajectories, and role in society, mothers face a variety of challenges and penalties that are not adequately addressed by public policy. Following the birth of a child, it’s well documented that working mothers face a “motherhood wage penalty,” which entails lower wages than women who did not have a child (Waldfogel, 1998; Anderson, Binder, and Krause, 2002; Kelven et al., 2019). Maternity leave may combat this penalty as it allows women to return to their jobs following the birth of a child – encouraging them to remain attached to the labor force (Rossin-Slater, 2017). However, as of this writing, the U.S. only offers up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave through the FMLA, which extends coverage to less than 60% of all workers. 5 And even if a mother is able to return to work, childcare in the U.S. is costly and often inaccessible for many. Families with infants can be expected to pay around $11,000 a year for childcare and subsidies are only available for 1 in 6 children that are eligible under the federal program. 6 Without a federal paid leave policy and access to affordable childcare, the U.S. lacks the infrastructure to adequately support mothers, and especially working mothers – making the prospect of motherhood financially unworkable for some.

This is relevant when considering that the women who seek abortions tend to be low-income mothers experiencing disruptive life events. In the most recent survey of abortion patients conducted by the Guttmacher Institute, 97% are adults, 49% are living below the poverty line, 59% already have children, and 55% are experiencing a disruptive life event such as losing a job, breaking up with a partner, or falling behind on rent (Jones and Jerman, 2017a and 2017b). It is not a stretch to imagine that access to abortion could be pivotal to these women’s financial lives, and recent evidence from “The Turnaway Study” 7 provides empirical support for this supposition. In this study, an interdisciplinary team of researchers follows two groups of women who were typically seeking abortions in the second trimester: one group that arrived at abortion clinics and learned they were just over the gestational age threshold for abortions and were “turned away” and a second that was just under the threshold and were provided an abortion. Miller, Wherry, and Foster (2020) match individuals in both groups to their Experian credit reports and observe that in the months leading up to the moment they sought an abortion, financial outcomes for both groups were trending similarly. At the moment one group is turned away from a wanted abortion, however, they began to experience substantial financial distress, exhibiting a 78% increase in past-due debt and an 81% increase in public records related to bankruptcies, evictions, and court judgments.

If Roe were overturned, the number of women experiencing substantial obstacles to obtaining an abortion would dramatically increase.

If Roe were overturned, the number of women experiencing substantial obstacles to obtaining an abortion would dramatically increase. Twelve states have enacted “trigger bans” designed to outlaw abortion in the immediate aftermath of a Roe reversal, while an additional 10 are considered highly likely to quickly enact new bans. 8 These bans would shutter abortion facilities across a wide swath of the American south and midwest, dramatically increasing travel distances and the logistical costs of obtaining an abortion. Economics research predicts what is likely to happen next. Multiple teams of economists have exploited natural experiments arising from mandatory waiting periods (Joyce and Kaestner, 2001; Lindo and Pineda-Torres, 2021; Myers, 2021) and provider closures (Quast, Gonzalez, and Ziemba, 2017; Fischer, Royer, and White, 2018; Lindo, Myers, Schlosser, and Cunningham, 2020; Venator and Fletcher, 2021; Myers, 2021). All have found that increases in travel distances prevent large numbers of women seeking abortions from reaching a provider and that most of these women give birth as a result. For instance, Lindo and co-authors (2020) exploit a natural experiment arising from the sudden closure of half of Texas’s abortion clinics in 2013 and find that an increase in travel distance from 0 to 100 miles results in a 25.8% decrease in abortions. Myers, Jones, and Upadhyay (2019) use these results to envision a post- Roe United States, forecasting that if Roe is overturned and the expected states begin to ban abortions, approximately 1/3 of women living in affected regions would be unable to reach an abortion provider, amounting to roughly 100,000 women in the first year alone.

Restricting, or outright eliminating, abortion access by overturning Roe v. Wade would diminish women’s personal and economic lives, as well as the lives of their families.

Whether one’s stance on abortion access is driven by deeply held views on women’s bodily autonomy or when life begins, the decades of research using rigorous methods is clear: there is a causal link between access to abortion and whether, when, and under what circumstances women become mothers, with ripple effects throughout their lives. Access affects their education, earnings, careers, and the subsequent life outcomes for their children. In the state’s argument, Mississippi rejects the causal link between access to abortion and societal outcomes established by economists and states that the availability of abortion isn’t relevant to women’s full participation in society. Economists provide clear evidence that overturning Roe would prevent large numbers of women experiencing unintended pregnancies—many of whom are low-income and financially vulnerable mothers—from obtaining desired abortions. Restricting, or outright eliminating, that access by overturning Roe v. Wade would diminish women’s personal and economic lives, as well as the lives of their families.

Caitlin Knowles Myers did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article. She has received financial compensation from Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the Center for Reproductive Rights for serving as an expert witness in litigation involving abortion regulations. She has not and will not receive financial compensation for her role in the amicus brief described here. Other than the aforementioned, she has not received financial support from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. Caitlin Knowles Myers is not currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with a financial or political interest in this article.

Abboud, Ali, 2019. “The Impact of Early Fertility Shocks on Women’s Fertility and Labor Market Outcomes.” Available from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3512913

Anderson, Deborah J., Binder, Melissa, and Kate Krause, 2002. “The motherhood wage penalty: Which mothers pay it and why?” The American Economic Review 92(2). Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/000282802320191606

Ananat, Elizabeth Oltmans, Gruber, Jonathan, Levine, Phillip and Douglas Staiger, 2009. “Abortion and Selection.” The Review of Economic Statistics 91(1). Retrieved from https://direct.mit.edu/rest/article-abstract/91/1/124/57736/Abortion-and-Selection?redirectedFrom=fulltext .

Angrist, Joshua D., and Alan B. Krueger, 1999. “Does Compulsory School Attendance Affect Schooling and Earnings?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(4). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2307/2937954 .

Angrist, Joshua D., and William N. Evans, 1996. “Schooling and Labor Market Consequences of the 1970 State Abortion Reforms.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 5406. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w5406 .

Angrist, Joshua D., and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, 2010. “The Credibility Revolution in Empirical Economics: How Better Research Design Is Taking the Con out of Econometrics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(2). Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.24.2.3

Bailey, Martha J., Hoynes, Hilary W., Rossin-Slater, Maya and Reed Walker, 2020. “Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Large-Scale Evidence from the Food Stamps Program” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26942 , Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w26942

Bitler, Marianne, and Madeline Zavodny, 2002a. “Did Abortion Legalization Reduce the Number of Unwanted Children? Evidence from Adoptions.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34 (1): 25-33. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3030229?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Bitler, Marianne, and Madeline Zavodny, 2002b. “Child Abuse and Abortion Availability.” American Economic Review , 92 (2): 363-367. Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/000282802320191624

Bitler, Marianne, and Madeline Zavodny, 2004. “Child Maltreatment, Abortion Availability, and Economic Conditions.” Review of Economics of the Household 2: 119-141. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1023/B:REHO.0000031610.36468.0e

Farin, Sherajum Monira, Hoehn-Velasco, Lauren, and Michael Pesko, 2021. “The Impact of Legal Abortion on Maternal Health: Looking to the Past to Inform the Present.” Retrieved from SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3913899

Finer, Lawrence B., and Mia R. Zolna, 2016. “Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011” New England Journal of Medicine 374. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26962904/

Finer, Lawrence B., Lindberg, Laura, D., and Sheila Desai. “A prospective measure of unintended pregnancy in the United States.” Contraception 98(6). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29879398/

Fischer, Stefanie, Royer, Heather, and Corey White, 2017. “The Impacts of Reduced Access to Abortion and Family Planning Services on Abortion, Births, and Contraceptive Purchases.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 23634 . Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w23634

Gruber, Jonathan, Levine, Phillip, and Douglas Staiger, 1999. “Abortion Legalization and Child Living Circumstances: Who Is the ‘Marginal Child’?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 114. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556007

Guldi, Melanie, 2008. “Fertility effects of abortion and birth control pill access for minors.” Demography 45 . Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0026

Hoynes, Hilary, Schanzenbach, Diane Whitmore, and Douglas Almond, 2016. “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net.” American Economic Review 106(4). Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20130375

Jones, Kelly, 2021. “At a Crossroads: The Impact of Abortion Access on Future Economic Outcomes.” American University Working Paper . Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17606/0Q51-0R11 .

Jones, Rachel K., Witwer, Elizabeth, Jerman, Jenna, September 18, 2018. “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017.” Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/ default/files/report_pdf/abortion-inciden ce-service-availability-us-2017.

Jones Rachel K., and Janna Jerman, 2017a. ”Population group abortion rates and lifetime incidence of abortion: United States, 2008–2014.” American Journal of Public Health 107 (12). Retrieved from https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042

Jones, Rachel K. and Jenna Jerman, 2017b. “Characteristics and Circumstances of U.S. Women Who Obtain Very Early and Second-Trimester Abortions.” PLoS One . Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28121999/

Joyce, Ted, and Robert Kaestner, 2001. “The Impact of Mandatory Waiting Periods and Parental Consent Laws on the Timing of Abortion and State of Occurrence among Adolescents in Mississippi and South Carolina.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20(2) . Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3325799 .

Kalist, David E., 2004. “Abortion and Female Labor Force Participation: Evidence Prior to Roe v. Wade.” Journal of Labor Research 25 (3) .

Keiser, David, and Joseph Shapiro, 2019. “Consequences of the Clean Water Act and the Demand for Water Quality.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134 (1).

Kleven, Henrik, Landais, Camille, Posch, Johanna, Steinhauer, Andreas, and Josef Zweimuleler, 2019. “Child Penalties Across Countries: Evidence and Explanations.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 109. Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20191078/

Levine, Phillip, Staiger, Douglas, Kane, Thomas, and David Zimmerman, 1999. “Roe v. Wade and American Fertility.” American Journal Of Public Health 89(2) . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1508542/

Lindo, Jason M., Myers, Caitlin Knowles, Schlosser, Andrea, and Scott Cunningham, 2020. “How Far Is Too Far? New Evidence on Abortion Clinic Closures, Access, and Abortions” Journal of Human Resources 55. Retrieved from http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/55/4/1137.refs

Lindo, Jason M., Pineda-Torres, Mayra, Pritchard, David, and Hedieh Tajali, 2020. “Legal Access to Reproductive Control Technology, Women’s Education, and Earnings Approaching Retirement.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 110. Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20201108

Lindo, Jason M., and Mayra Pineda-Torres, 2021. “New Evidence on the Effects of Mandatory Waiting Periods for Abortion.” J ournal of Health Econ omics. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34607119/

Miguel, Edward, Satyanath, Shanker, and Ernest Sergenti, 2004. “Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 112(4). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/421174

Miller, Sarah, Wherry, Laura R., and Diana Greene Foster, 2020. “The Economic Consequences of Being Denied an Abortion.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 26662 . Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w26662 .

Myers, Caitlin Knowles, 2017. “The Power of Abortion Policy: Reexamining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control” Journal of Political Economy 125(6) . Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1086/694293 .

Myers, Caitlin Knowles, Jones, Rachel, and Ushma Upadhyay, 2019. “Predicted changes in abortion access and incidence in a post-Roe world.” Contraception 100(5). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31376381/

Myers, Caitlin Knowles, 2021. “Cooling off or Burdened? The Effects of Mandatory Waiting Periods on Abortions and Births.” IZA Institute of Labor Economics No. 14434. Retrieved from https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/14434/cooling-off-or-burdened-the-effects-of-mandatory-waiting-periods-on-abortions-and-births

Quast, Troy, Gonzalez, Fidel, and Robert Ziemba, 2017. “Abortion Facility Closings and Abortion Rates in Texas.” Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing 54 . Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0046958017700944

Rossin-Slater, Maya, 2017. “Maternity and Family Leave Policy.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 23069. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w23069

Venator, Joanna, and Jason Fletcher, 2020. “Undue Burden Beyond Texas: An Analysis of Abortion Clinic Closures, Births, and Abortions in Wisconsin.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 40(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22263

Waldfogel, Jane, 1998. “The family gap for young women in the United States and Britain: Can maternity leave make a difference?” Journal of Labor Economics 16(3).

- Thomas E. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Brief in Support of Petitioners, No. 19-1392.

- Thomas E. Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Brief for Petitioners, No. 19-139, Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/19/19-1392/184703/20210722161332385_19-1392BriefForPetitioners.pdf

- The Nobel Prize. 2021. “Press release: The Prize in Economic Sciences 202.” Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2021/press-release/

- See Angrist and Evans (1996), Gruber et al. (1999), Ananat et al. (2009), Guldi (2008), Myers (2017), Abboud (2019), Jones (2021).

- Brown, Scott, Herr, Jane, Roy, Radha , and Jacob Alex Klerman, July 2020. “Employee and Worksite Perspectives of the FMLA Who Is Eligible?” U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/WHD_FMLA2018PB1WhoIsEligible_StudyBrief_Aug2020.pdf

- Whitehurst, Grover J., April 19, 2018. “What is the market price of daycare and preschool?” Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-is-the-market-price-of-daycare-and-preschool/; Chien, Nina, 2021. “Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2018.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/20 21-08/cy-2018-child-care-subsidy-eligibility.pdf

- Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (NSIRH). “The Turnaway Study.” Retrieved from https://www.ansirh.org/research/ongoing/turnaway-study.

- Center for Reproductive Rights, 2021. “What If Roe Fell?” Retrieved from https://maps.reproductiverights.org/what-if-roe-fell

Economic Studies

Center for Economic Security and Opportunity

William A. Galston

March 28, 2024

March 25, 2024

William G. Gale

March 13, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Rom J Morphol Embryol

- v.61(1); Jan-Mar 2020

A research on abortion: ethics, legislation and socio-medical outcomes. Case study: Romania

Andreea mihaela niţă.

1 Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Craiova, Romania

Cristina Ilie Goga

This article presents a research study on abortion from a theoretical and empirical point of view. The theoretical part is based on the method of social documents analysis, and presents a complex perspective on abortion, highlighting items of medical, ethical, moral, religious, social, economic and legal elements. The empirical part presents the results of a sociological survey, based on the opinion survey method through the application of the enquiry technique, conducted in Romania, on a sample of 1260 women. The purpose of the survey is to identify Romanians perception on the decision to voluntary interrupt pregnancy, and to determine the core reasons in carrying out an abortion.

The analysis of abortion by means of medical and social documents

Abortion means a pregnancy interruption “before the fetus is viable” [ 1 ] or “before the fetus is able to live independently in the extrauterine environment, usually before the 20 th week of pregnancy” [ 2 ]. “Clinical miscarriage is both a common and distressing complication of early pregnancy with many etiological factors like genetic factors, immune factors, infection factors but also psychological factors” [ 3 ]. Induced abortion is a practice found in all countries, but the decision to interrupt the pregnancy involves a multitude of aspects of medical, ethical, moral, religious, social, economic, and legal order.

In a more simplistic manner, Winston Nagan has classified opinions which have as central element “abortion”, in two major categories: the opinion that the priority element is represented by fetus and his entitlement to life and the second opinion, which focuses around women’s rights [ 4 ].

From the medical point of view, since ancient times there have been four moments, generally accepted, which determine the embryo’s life: ( i ) conception; ( ii ) period of formation; ( iii ) detection moment of fetal movement; ( iv ) time of birth [ 5 ]. Contemporary medicine found the following moments in the evolution of intrauterine fetal: “ 1 . At 18 days of pregnancy, the fetal heartbeat can be perceived and it starts running the circulatory system; 2 . At 5 weeks, they become more clear: the nose, cheeks and fingers of the fetus; 3 . At 6 weeks, they start to function: the nervous system, stomach, kidneys and liver of the fetus, and its skeleton is clearly distinguished; 4 . At 7 weeks (50 days), brain waves are felt. The fetus has all the internal and external organs definitively outlined. 5 . At 10 weeks (70 days), the unborn child has all the features clearly defined as a child after birth (9 months); 6 . At 12 weeks (92 days, 3 months), the fetus has all organs definitely shaped, managing to move, lacking only the breath” [ 6 ]. Even if most of the laws that allow abortion consider the period up to 12 weeks acceptable for such an intervention, according to the above-mentioned steps, there can be defined different moments, which can represent the beginning of life. Nowadays, “abortion is one of the most common gynecological experiences and perhaps the majority of women will undergo an abortion in their lifetimes” [ 7 ]. “Safe abortions carry few health risks, but « every year, close to 20 million women risk their lives and health by undergoing unsafe abortions » and 25% will face a complication with permanent consequences” [ 8 , 9 ].

From the ethical point of view, most of the times, the interruption of pregnancy is on the border between woman’s right over her own body and the child’s (fetus) entitlement to life. Judith Jarvis Thomson supported the supremacy of woman’s right over her own body as a premise of freedom, arguing that we cannot force a person to bear in her womb and give birth to an unwanted child, if for different circumstances, she does not want to do this [ 10 ]. To support his position, the author uses an imaginary experiment, that of a violinist to which we are connected for nine months, in order to save his life. However, Thomson debates the problem of the differentiation between the fetus and the human being, by carrying out a debate on the timing which makes this difference (period of conception, 10 weeks of pregnancy, etc.) and highlighting that for people who support abortion, the fetus is not an alive human being [ 10 ].

Carol Gilligan noted that women undergo a true “moral dilemma”, a “moral conflict” with regards to voluntary interruption of pregnancy, such a decision often takes into account the human relationships, the possibility of not hurting the others, the responsibility towards others [ 11 ]. Gilligan applied qualitative interviews to a number of 29 women from different social classes, which were put in a position to decide whether or not to commit abortion. The interview focused on the woman’s choice, on alternative options, on individuals and existing conflicts. The conclusion was that the central moral issue was the conflict between the self (the pregnant woman) and others who may be hurt as a result of the potential pregnancy [ 12 ].

From the religious point of view, abortion is unacceptable for all religions and a small number of abortions can be seen in deeply religious societies and families. Christianity considers the beginning of human life from conception, and abortion is considered to be a form of homicide [ 13 ]. For Christians, “at the same time, abortion is giving up their faith”, riot and murder, which means that by an abortion we attack Jesus Christ himself and God [ 14 ]. Islam does not approve abortion, relying on the sacral life belief as specified in Chapter 6, Verse 151 of the Koran: “Do not kill a soul which Allah has made sacred (inviolable)” [ 15 ]. Buddhism considers abortion as a negative act, but nevertheless supports for medical reasons [ 16 ]. Judaism disapproves abortion, Tanah considering it to be a mortal sin. Hinduism considers abortion as a crime and also the greatest sin [ 17 ].

From the socio-economic point of view, the decision to carry out an abortion is many times determined by the relations within the social, family or financial frame. Moreover, studies have been conducted, which have linked the legalization of abortions and the decrease of the crime rate: “legalized abortion may lead to reduced crime either through reductions in cohort sizes or through lower per capita offending rates for affected cohorts” [ 18 ].

Legal regulation on abortion establishes conditions of the abortion in every state. In Europe and America, only in the XVIIth century abortion was incriminated and was considered an insignificant misdemeanor or a felony, depending on when was happening. Due to the large number of illegal abortions and deaths, two centuries later, many states have changed legislation within the meaning of legalizing voluntary interruption of pregnancy [ 6 ]. In contemporary society, international organizations like the United Nations or the European Union consider sexual and reproductive rights as fundamental rights [ 19 , 20 ], and promotes the acceptance of abortion as part of those rights. However, not all states have developed permissive legislation in the field of voluntary interruption of pregnancy.

Currently, at national level were established four categories of legislation on pregnancy interruption area:

( i ) Prohibitive legislations , ones that do not allow abortion, most often outlining exceptions in abortion in cases where the pregnant woman’s life is endangered. In some countries, there is a prohibition of abortion in all circumstances, however, resorting to an abortion in the case of an imminent threat to the mother’s life. Same regulation is also found in some countries where abortion is allowed in cases like rape, incest, fetal problems, etc. In this category are 66 states, with 25.5% of world population [ 21 ].

( ii ) Restrictive legislation that allow abortion in cases of health preservation . Loosely, the term “health” should be interpreted according to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition as: “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [ 22 ]. This type of legislation is adopted in 59 states populated by 13.8% of the world population [ 21 ].

( iii ) Legislation allowing abortion on a socio-economic motivation . This category includes items such as the woman’s age or ability to care for a child, fetal problems, cases of rape or incest, etc. In this category are 13 countries, where we have 21.3% of the world population [ 21 ].

( iv ) Legislation which do not impose restrictions on abortion . In the case of this legislation, abortion is permitted for any reason up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, with some exceptions (Romania – 14 weeks, Slovenia – 10 weeks, Sweden – 18 weeks), the interruption of pregnancy after this period has some restrictions. This type of legislation is adopted in 61 countries with 39.5% of the world population [21].

The Centre for Reproductive Rights has carried out from 1998 a map of the world’s states, based on the legislation typology of each country (Figure (Figure1 1 ).

The analysis of states according to the legislation regarding abortion. Source: Centre for Reproductive Rights. The World’s Abortion Laws, 2018 [ 23 ]

An unplanned pregnancy, socio-economic context or various medical problems [ 24 ], lead many times to the decision of interrupting pregnancy, regardless the legislative restrictions. In the study “Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008” issued in 2011 by the WHO , it was determined that within the states with restrictive legislation on abortion, we may also encounter a large number of illegal abortions. The illegal abortions may also be resulting in an increased risk of woman’s health and life considering that most of the times inappropriate techniques are being used, the hygienic conditions are precarious and the medical treatments are incorrectly administered [ 25 ]. Although abortions done according to medical guidelines carry very low risk of complications, 1–3 unsafe abortions contribute substantially to maternal morbidity and death worldwide [ 26 ].

WHO has estimated for the year 2008, the fact that worldwide women between the ages of 15 and 44 years carried out 21.6 million “unsafe” abortions, which involved a high degree of risk and were distributed as follows: 0.4 million in the developed regions and a number of 21.2 million in the states in course of development [ 25 ].

Case study: Romania

Legal perspective on abortion

In Romania, abortion was brought under regulation by the first Criminal Code of the United Principalities, from 1864.

The Criminal Code from 1864, provided the abortion infringement in Article 246, on which was regulated as follows: “Any person, who, using means such as food, drinks, pills or any other means, which will consciously help a pregnant woman to commit abortion, will be punished to a minimum reclusion (three years).

The woman who by herself shall use the means of abortion, or would accept to use means of abortion which were shown or given to her for this purpose, will be punished with imprisonment from six months to two years, if the result would be an abortion. In a situation where abortion was carried out on an illegitimate baby by his mother, the punishment will be imprisonment from six months to one year.

Doctors, surgeons, health officers, pharmacists (apothecary) and midwives who will indicate, will give or will facilitate these means, shall be punished with reclusion of at least four years, if the abortion took place. If abortion will cause the death of the mother, the punishment will be much austere of four years” (Art. 246) [ 27 ].

The Criminal Code from 1864, reissued in 1912, amended in part the Article 246 for the purposes of eliminating the abortion of an illegitimate baby case. Furthermore, it was no longer specified the minimum of four years of reclusion, in case of abortion carried out with the help of the medical staff, leaving the punishment to the discretion of the Court (Art. 246) [ 28 ].

The Criminal Code from 1936 regulated abortion in the Articles 482–485. Abortion was defined as an interruption of the normal course of pregnancy, being punished as follows:

“ 1 . When the crime is committed without the consent of the pregnant woman, the punishment was reformatory imprisonment from 2 to 5 years. If it caused the pregnant woman any health injury or a serious infirmity, the punishment was reformatory imprisonment from 3 to 6 years, and if it has caused her death, reformatory imprisonment from 7 to 10 years;

2 . When the crime was committed by the unmarried pregnant woman by herself, or when she agreed that someone else should provoke the abortion, the punishment is reformatory imprisonment from 3 to 6 months, and if the woman is married, the punishment is reformatory imprisonment from 6 months to one year. Same penalty applies also to the person who commits the crime with the woman’s consent. If abortion was committed for the purpose of obtaining a benefit, the punishment increases with another 2 years of reformatory imprisonment.

If it caused the pregnant woman any health injuries or a severe disablement, the punishment will be reformatory imprisonment from one to 3 years, and if it has caused her death, the punishment is reformatory imprisonment from 3 to 5 years” (Art. 482) [ 29 ].

The criminal legislation from 1936 specifies that it is not considered as an abortion the interruption from the normal course of pregnancy, if it was carried out by a doctor “when woman’s life was in imminent danger or when the pregnancy aggravates a woman’s disease, putting her life in danger, which could not be removed by other means and it is obvious that the intervention wasn’t performed with another purpose than that of saving the woman’s life” and “when one of the parents has reached a permanent alienation and it is certain that the child will bear serious mental flaws” (Art. 484, Par. 1 and Par. 2) [ 29 ].

In the event of an imminent danger, the doctor was obliged to notify prosecutor’s office in writing, within 48 hours after the intervention, on the performance of the abortion. “In the other cases, the doctor was able to intervene only with the authorization of the prosecutor’s office, given on the basis of a medical certificate from hospital or a notice given as a result of a consultation between the doctor who will intervene and at least a professor doctor in the disease which caused the intervention. General’s Office Prosecutor, in all cases provided by this Article, shall be obliged to maintain the confidentiality of all communications or authorizations, up to the intercession of any possible complaints” (Art. 484) [ 29 ].

The legislation of 1936 provided a reformatory injunction from one to three years for the abortions committed by doctors, sanitary agents, pharmacists, apothecary or midwives (Art. 485) [ 29 ].

Abortion on demand has been legalized for the first time in Romania in the year 1957 by the Decree No. 463, under the condition that it had to be carried out in a hospital and to be carried out in the first quarter of the pregnancy [ 30 ]. In the year 1966, demographic policy of Romania has dramatically changed by introducing the Decree No. 770 from September 29 th , which prohibited abortion. Thus, the voluntary interruption of pregnancy became a crime, with certain exceptions, namely: endangering the mother’s life, physical or mental serious disability; serious or heritable illness, mother’s age over 45 years, if the pregnancy was a result of rape or incest or if the woman gave birth to at least four children who were still in her care (Art. 2) [ 31 ].

In the Criminal Code from 1968, the abortion crime was governed by Articles 185–188.

The Article 185, “the illegal induced abortion”, stipulated that “the interruption of pregnancy by any means, outside the conditions permitted by law, with the consent of the pregnant woman will be punished with imprisonment from one to 3 years”. The act referred to above, without the prior consent from the pregnant woman, was punished with prison from two to five years. If the abortion carried out with the consent of the pregnant woman caused any serious body injury, the punishment was imprisonment from two to five years, and when it caused the death of the woman, the prison sentence was from five to 10 years. When abortion was carried out without the prior consent of the woman, if it caused her a serious physical injury, the punishment was imprisonment from three to six years, and if it caused the woman’s death, the punishment was imprisonment from seven to 12 years (Art. 185) [ 32 ].

“When abortion was carried out in order to obtain a material benefit, the maximum punishment was increased by two years, and if the abortion was made by a doctor, in addition to the prison punishment could also be applied the prohibition to no longer practice the profession of doctor”.

Article 186, “abortion caused by the woman”, stipulated that “the interruption of the pregnancy course, committed by the pregnant woman, was punished with imprisonment from 6 months to 2 years”, quoting the fact that by the same punishment was also sanctioned “the pregnant woman’s act to consent in interrupting the pregnancy course made out by another person” (Art. 186) [ 26 ].

The Regulations of the Criminal Code in 1968, also provided the crime of “ownership of tools or materials that can cause abortion”, the conditions of this holding being met when these types of instruments were held outside the hospital’s specialized institutions, the infringement shall be punished with imprisonment from three months to one year (Art. 187) [ 32 ].

Furthermore, the doctors who performed an abortion in the event of extreme urgency, without prior legal authorization and if they did not announce the competent authority within the legal deadline, they were punished by imprisonment from one month to three months (Art. 188) [ 32 ].

In the year 1985, it has been issued the Decree No. 411 of December 26 th , by which the conditions imposed by the Decree No. 770 of 1966 have been hardened, meaning that it has increased the number of children, that a woman could have in order to request an abortion, from four to five children [ 33 ].

The Articles 185–188 of the Criminal Code and the Decree No. 770/1966 on the interruption of the pregnancy course have been abrogated by Decree-Law No. 1 from December 26 th , 1989, which was published in the Official Gazette No. 4 of December 27 th , 1989 (Par. 8 and Par. 12) [ 34 ].