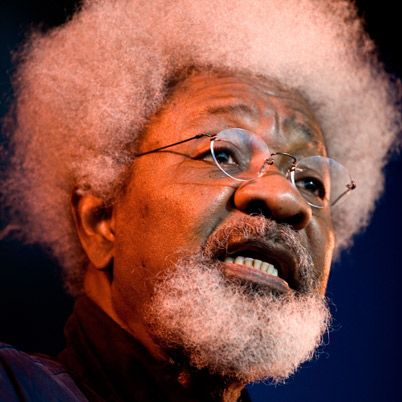

Wole Soyinka

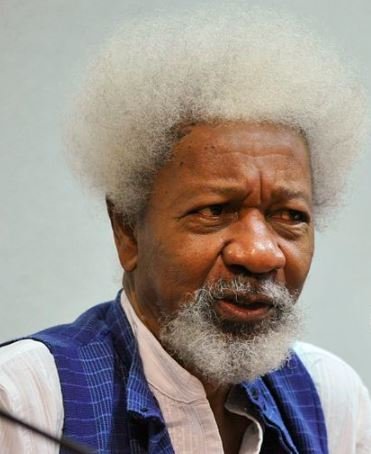

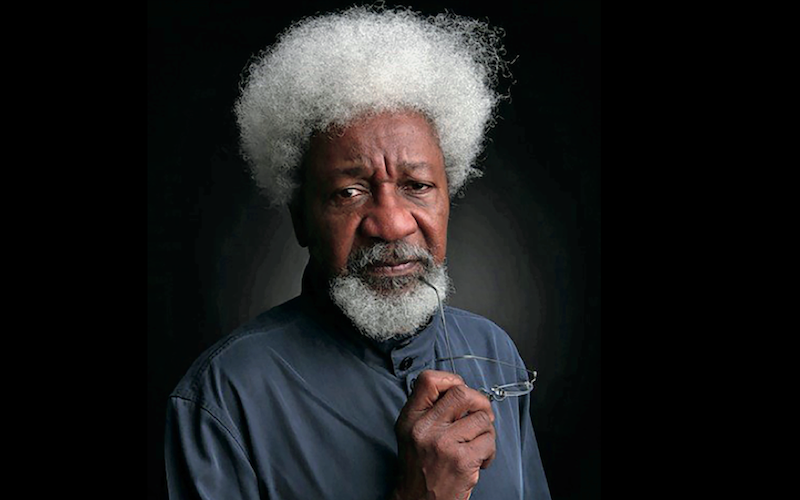

Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright, poet, author, teacher and political activist. In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Who Is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka was born in Nigeria and educated in England. In 1986, the playwright and political activist became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. He dedicated his Nobel acceptance speech to Nelson Mandela . Soyinka has published hundreds of works, including drama, novels, essays and poetry, and colleges all over the world seek him out as a visiting professor.

Wole Soyinka was born Akinwande Oluwole "Wole" Babatunde Soyinka on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, near Ibadan in western Nigeria. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a prominent Anglican minister and headmaster. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, who was called "Wild Christian," was a shopkeeper and local activist. As a child, he lived in an Anglican mission compound, learning the Christian teachings of his parents, as well as the Yoruba spiritualism and tribal customs of his grandfather. A precocious and inquisitive child, Wole prompted the adults in his life to warn one another: “He will kill you with his questions.”

After finishing preparatory university studies in 1954 at Government College in Ibadan, Soyinka moved to England and continued his education at the University of Leeds, where he served as the editor of the school's magazine, The Eagle . He graduated with a bachelor's degree in English literature in 1958. (In 1972 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate).

Plays & Political Activism

In the late 1950s Soyinka wrote his first important play, A Dance of the Forests , which satirized the Nigerian political elite. From 1958 to 1959, Soyinka was a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. In 1960, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship and returned to Nigeria to study African drama.

In 1960, he founded the theater group, The 1960 Masks, and in 1964, the Orisun Theatre Company, in which he produced his own plays and performed as an actor. He has periodically been a visiting professor at the universities of Cambridge, Sheffield, and Yale.

"The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism."

Soyinka is also a political activist, and during the civil war in Nigeria he appealed in an article for a cease-fire. He was arrested for this in 1967, and held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969.

Nobel Prize and Later Career

In 1986, upon awarding Soyinka with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the committee said the playwright "in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence." Soyinka sometimes writes of modern West Africa in a satirical style, but his serious intent and his belief in the evils inherent in the exercise of power are usually present in his work. To date, Soyinka has published hundreds of works.

In addition to drama and poetry, he has written two novels, The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anom y (1973), as well as autobiographical works including The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), a gripping account of his prison experience, and Aké ( 1981), a memoir about his childhood. Myth, Literature and the African World (1975) is a collection of Soyinka’s literary essays.

“Against my rational instincts, I believe that we have here a genuine case of a born-again democrat,” he said. Ultimately, “the real heroes of this exercise have been the Nigerian people and that gingers me up.”

Now considered Nigeria’s foremost man of letters, Soyinka is still politically active and spent the 2015 election day in Africa’s biggest democracy working the phones to monitor reports of voting irregularities, technical issues and violence, according to The Guardian . After the election on March 28, 2015, he said that Nigerians must show a Nelson Mandela–like ability to forgive president-elect Muhammadu Buhari’s past as an iron-fisted military ruler, according to Bloomberg.com.

Personal Life

Soyinka has been married three times. He married British writer Barbara Dixon in 1958; Olaide Idowu, a Nigerian librarian, in 1963; and Folake Doherty, his current wife, in 1989. In 2014, Soyinka revealed he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and cured 10 months after treatment.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Wole Soyinka

- Birth Year: 1934

- Birth date: July 13, 1934

- Birth City: Abeokuta

- Birth Country: Nigeria

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Wole Soyinka is a Nigerian playwright, poet, author, teacher and political activist. In 1986, he became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

- Writing and Publishing

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- University College

- University of Leeds

- Government College

- Nationalities

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- A tiger doesn't proclaim his tigritude, he pounces.

- Under a dictatorship, a nation ceases to exist. All that remains is a fiefdom, a planet of slaves regimented by aliens from outer space.

- Books and all forms of writing are terror to those who wish to suppress the truth.

- The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.

Nobel Prize Winners

Alice Munro

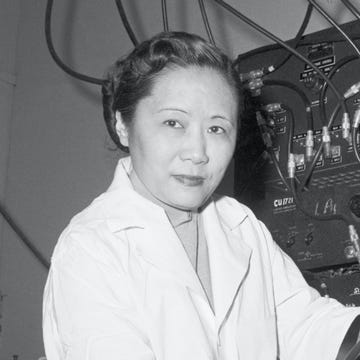

Chien-Shiung Wu

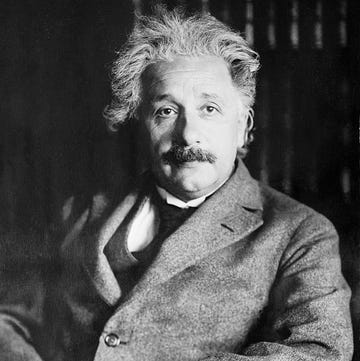

The Solar Eclipse That Made Albert Einstein a Star

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

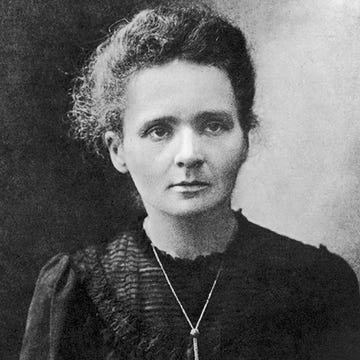

Marie Curie

Martin Luther King Jr.

Henry Kissinger

Malala Yousafzai

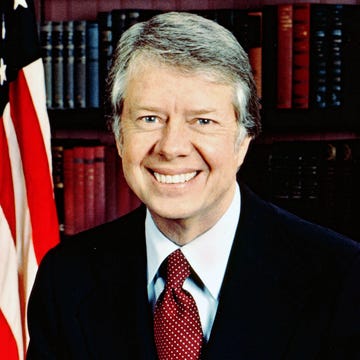

Jimmy Carter

10 Famous Poets Whose Enduring Works We Still Read

22 Famous Scientists You Should Know

Jean-Paul Sartre

World History Edu

- Africa / Renowned Writers

Wole Soyinka: Biography, Political Activism, Major Plays, Nobel Prize, & Achievements

by World History Edu · May 3, 2021

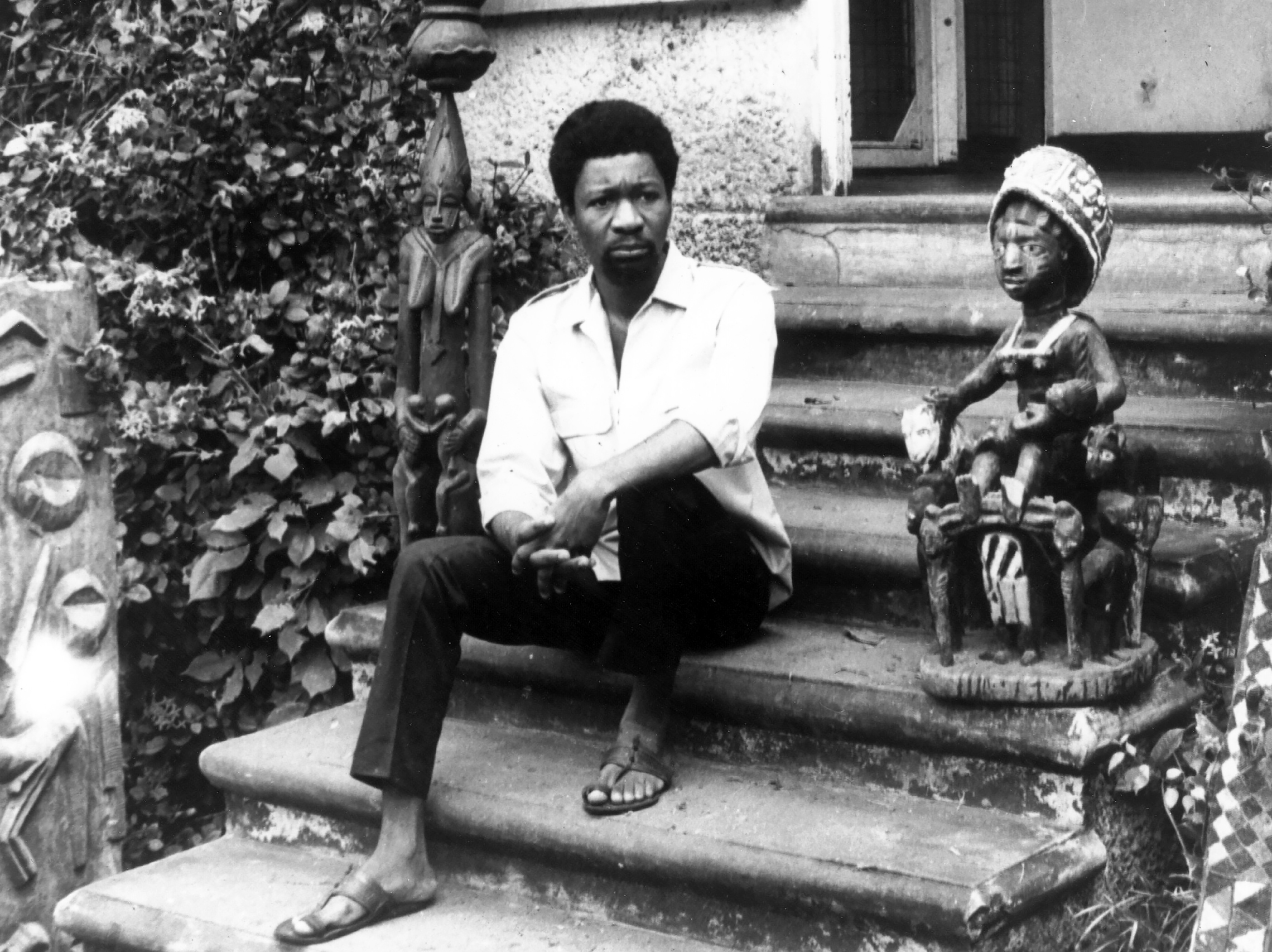

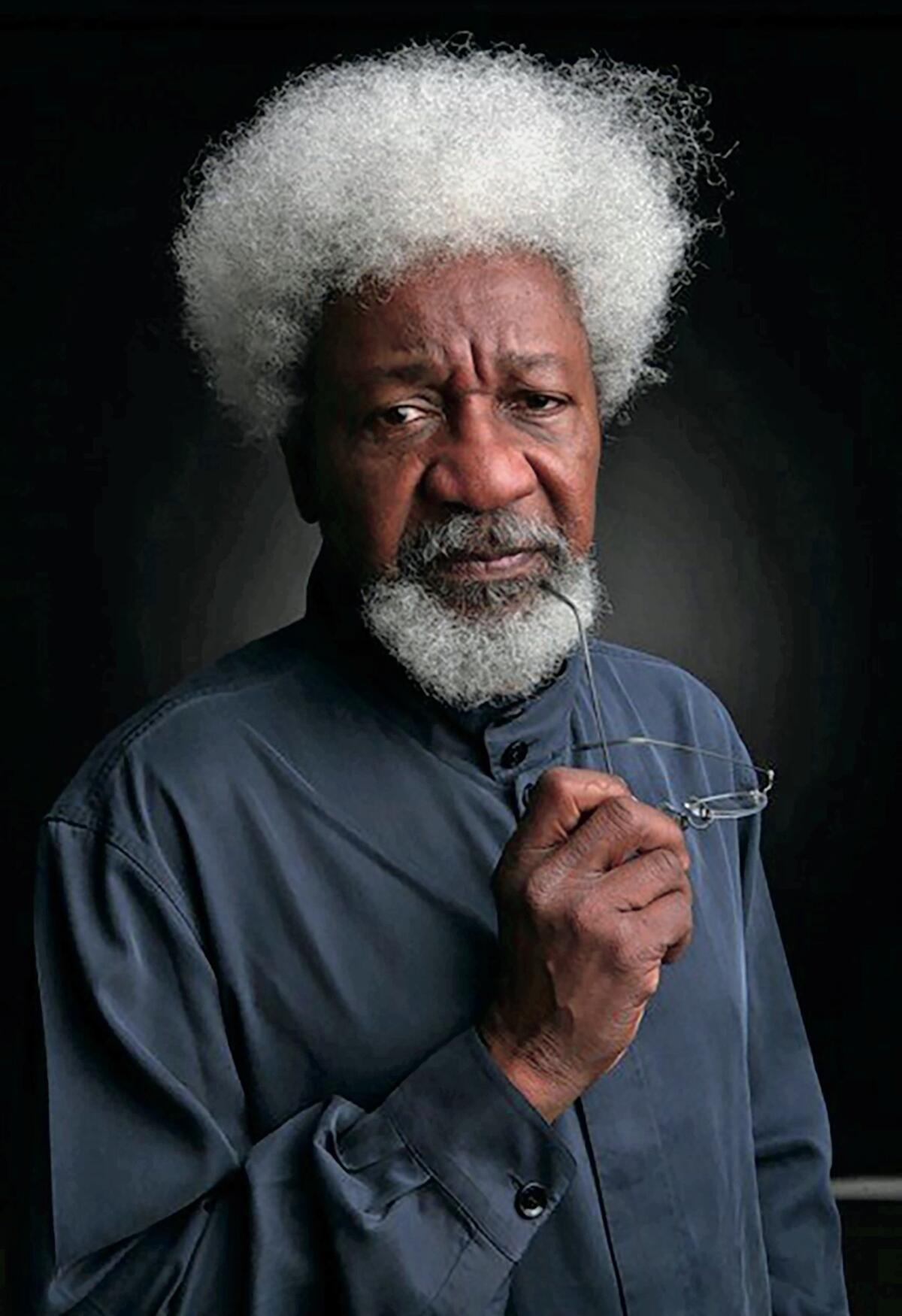

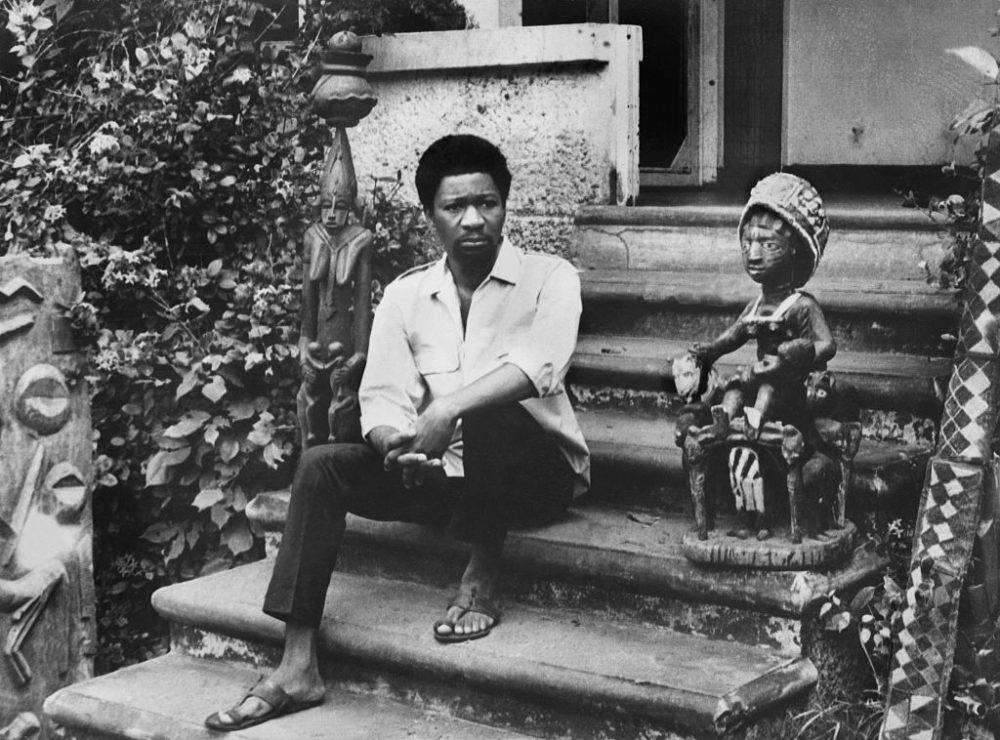

Wole Soyinka — Image courtesy — from the Nobel Foundation archive

In recent decades, very good playwrights have emerged from the African continent, but nowhere do they reach the excellence of Nigerian playwright and poet Wole Soyinka.

Most known for winning the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, Wole Soyinka has written critically acclaimed plays for both theatre and radio. He thus became the first sub-Saharan African to win a Nobel Prize.

Drawing heavily from Yoruba people’s myths, rites and cultural patterns, Soyinka, a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at Duke University, has attained incredible feats to the point where he is now considered one of the finest poetical playwrights of all time.

Wole Soyinka: Quick Facts

Born: Akinwande Ouwole “Wole” Soyinka

Birthday: July 13, 1934

Place of birth : Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria (formerly Nigeria Protectorate)

Parents: Grace Eniola Soyinka and Samuel Ayodele Soyinka

Siblings: Folashade (died at age one), Kayode, Omofolabo “Folabo”, Yeside, Femi, and Atinuke “Tinu”.

Education: Abeokuta Grammar School, Government College in Ibadan (1946-1952), University College Ibadan (1952-1954); University of Leeds

Spouses: Married three times and divorce twice: Barbara Dixon (married in 1958), Olaide Idowu (married in 1963), Folake Doherty (1989-)

Influenced by : Irish writer J.M. Synge, British literary scholar Molly Maureen Mahood

Most famous for : Works that help to advance understanding and the exchange of knowledge of different cultures and peoples

Notable awards and honors: Nobel Prize in Literature (1986), Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award (2009), Europe Theatre Prize in the “Special Prize” category (2017)

Who is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka is the son of Samuel Ayodele Soyinka and Grace Eniola. Both his parents grew up in strong Anglican values. His father for example was an Anglican minister and a headmaster of Anglican school in Abeokuta. His mother, a shop owner, was a political activist in Abeokuta.

His family belongs to the Yoruba people, one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria. As a result of his family’s Anglican background as well as the prevailing Yoruba religious tradition around him, he benefited tremendously from the merging of those two religious beliefs. As a matter of fact, many of his works were inspired by the culture and traditions of the Yoruba people.

Growing up, Soyinka attended a primary school in Abeokuta before studying at Government College in Ibadan, Nigeria. He then proceeded to the University of Ibadan (1952-1954) and then the University of Leeds in England (1957), where he studied drama. While at Leeds, he was tutored by the famous literary critic Wilson Knight.

While in the United Kingdom, he worked for some time as a dramturgist at the Royal Court Theater, London. Once back in Nigeria, Soyinka followed his passion and studied African drama before going on to teach drama and literature at the University of Lagos.

He also had teaching spells at his alma mater the University of Ibadan, and later Obafemi Awolowo University (formerly the University of Ife).

Like his famous aunt-in-law, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (the mother of Afro-Beat king Fela Kuti ), Soyinka was very active in Nigeria’s fight to gain independence from Great Britain.

Since 1975 Soyinka has been the professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Ibadan. He has on numerous occasions served as a visiting professor in universities in England and the U.S., including Yale, Cambridge, and Sheffield.

In November 1994 he fled his home country Nigeria (through Benin) after then-military ruler General Sani Abacha accused him of treasonous crimes. Soyinka made his way to the U.S., where he lived until Nigeria was returned to civilian rule following the death of Gen. Abacha in 1998.

In October 1994 Soyinka was appointed the UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture and human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication

Imprisonment during the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970)

Frustrated by the extent of cult of personality and rampant government corruption in his country, he began to firm statements critical of the Nigerian government, especially the January 1966 military coup

Beginning around 1967, Soyinka had secret talks with the Ibo community in a bid to avert a civil war from breaking out in Nigeria. He wrote a passionate article, appealing to both sides to exercise restraint. However, his good intentions were misread by the Nigeria government (headed by General Yakubu Gowon) who described him as a traitor.

Soyinka was subsequently imprisoned in 1967 on the charge of conspiring with the leaders of Biafra rebels. He remained locked up (in solitary confinement in some cases) for close to two years before his release in 1969.

Fight against oppressive governments and dictators

Soyinka does not mince words when it comes to rejecting the numerous military dictatorships that have blighted many African countries for decades. For example, he was very vocal in criticizing the brutal dictatorships of General Idi Amin of Uganda (1971-1979), Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (1987-2017), and Nigeria’s General Sani Abacha’s (1993-1998). The latter dictator, in a farce trial, sentenced Soyinka in absentia to death on the charge of treason against the state.

As a result of the frequent suppression of dissent in Nigeria by various military juntas of the past, Soyinka was forced to spend a bulk part of his adult life living in exile, particularly in countries such as the U.S. and the UK.

He has also relentlessly called on his Nigerian government to end the endemic corruption and abuse of powers by people placed in positions of trust.

Nobel Prize in Literature (1986)

In 1986, Soyinka became the first African to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. His works were deemed by the Swedish Academy in Stockholm, Sweden, as being “full of life and urgency”.

In his Nobel lecture , titled “This Past Must Address Its Present”, on December 8, 1986, he praised the invaluable contribution anti-apartheid fighter Nelson Mandela in ending the politics of racial segregation in not just South Africa, but across the world.

Two years after his 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature, he received the Agip Prize for Literature.

Major plays and essays

Broadcast in July 1954 by the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, Soyinka’s “Keffi’s Birthday Treat” was a short radio play that he wrote while studying in the U.K.

During his stay in London, he also wrote plays such as The Lion and the Jewel (1959) and The Swamp Dwellers (1958) . The latter play was a philosophical play with a touch of comedy, highlighting how Nigerians could blend development and tradition.

Other famous plays by Wole Soyinka

Drawing heavily from Yoruba people’s myths, rites and cultural patterns, Soyinka has attained incredible feats to the point where he is now considered one of the finest poetical playwrights of all time.

The following are some of his famous plays:

The Invention (1957) – Soyinka’s first play to be produced at the Royal Court Theatre, London

A Dance of the Forest (performed 1960, published in 1963)

The Strong Breed (performed 1966, published in 1963)

The Detainee (1964) – a radio play for the BBC in London

The Road (1965) – premiered in London at the Commonwealth Arts Festival in September, 1965

Kongi’s Harvest (performed 1965, published 1967)

Madmen and Specialists (performed in 1970, published in 1971)

Death and the King’s Horseman (performed in 1976, published in 1975)

Opera Wonyosi (performed in 1977, published in 1981)

A Play of Giants (1984)

Requiem for a Futurologist (1985)

Famous novels by Wole Soyinka

Some examples of Wole Soyinka famous novels are The Interpreters (1964) and Season of Anomy (1973). The latter delves into his thoughts during his time behind bars as political prisoner.

Wole Soyinka — A line from Soyinka’s 1960 essay for the Horn

More Wole Soyinka Facts

- In an interview in 2007, he stated that he although he attended church regularly and sang in the choir while growing up in Abeokuta, he went on to gravitate towards agnosticism in his adult life, which was then followed by “outright atheistic convictions”.

- Soyinka’s mother – Grace Eniola Soyinka – was a member of the Ransome-Kuti family. She was also the niece-in-law to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, the mother of Afro-Beat king Fela Kuti.

- Some notable first cousins (once removed) are Fela Kuti, Dr. Beko Ransome-Kuti, and politician Olikoye Ransome-Kuti. As a result, his second cousins are Femi Kuti Seun Kuti, and Yeni Kuti.

- Soyinka is a big admirer of Yoruba mythology, particularly the orisha (god) Ogun, the god of iron and war.

- Some of his most famous autobiographies are The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), which was banned by a Nigerian court in 1984, and Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981), which won the 1983 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

- Soyinka’s first essay “Towards a True Theater” was published in December 1962. He would go on to write several others, including Culture in Transition (1963), Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976), and The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- In 1960, Wole Soyinka founded a theatre group called The 1960 Masks. Four years later, in 1964, he founded the Orisun Theatre Company, producing many great plays and acting in a number of them.

- His 1963 play A Dance of the Forest (performed 1960, published 1963) was a brilliant work that exposed the flaws of the elites of Nigerian society. It was selected as the official play for the independence celebration on October 1, 1960.

- He released his first feature length film – Culture in Transition – in 1963.

- Soyinka briefly lived in Accra, Ghana, where he served as the editor of the literary magazine Transition. The magazine was very critical of numerous African dictators of that era, including Idi Amin, Uganda’s dictator of the 1970s.

Tags: Abeokuta-Nigeria African Writers Nigeria Nobel Prize in Literature Playwrights Poets Wole Soyinka

You may also like...

What is Western Sahara? – History and Major Facts

July 17, 2023

Rwandan Genocide – Summary, Death Toll, & Facts

December 20, 2020

Canaan Banana – Biography, Presidency, Death & Other Notable Facts

September 25, 2022

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Major Facts about Fela Kuti (1938-1997)

- Previous story Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Who were the three helpers of Tang Sanzang?

What was the Tetrarchy and why was it established by Emperor Diocletian?

What was the Ghana Empire known for?

Life and Major Accomplishments of Nicolaus Copernicus

What was life like on Mount Olympus?

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

How did Captain James Cook die?

Trail of Tears: Story, Death Count & Facts

5 Great Accomplishments of Ancient Greece

Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Medieval History Military Generals Military History Napoleon Bonaparte Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Ottoman Empire Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka on a Lifetime of Art and Activism

Aysegül sert talks to the nigerian writer in paris.

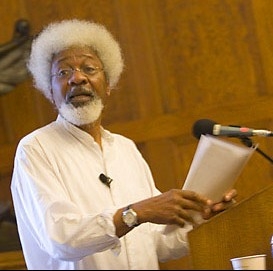

Wole Soyinka is writer-warrior: at 89, he still has his abundant hair, lanky frame and lavish beard, which give him the look of a charming mad scientist.

Born in 1934 in Abeokuta, in the forested land of the Yoruba region of southwestern Nigeria, he was the first African writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, winning in 1986. He studied in England, founded two theatre companies [in 1960 and 1964], is a professor of comparative literature, was primarily exiled in the U.S., and currently lives between Nigeria and California. His impact on the history of literature is rivaled only by his political activism. Jailed in his homeland in the sixties, he served twenty-two months in solitary confinement out of twenty-seven months of incarceration. His prolific work—over 45 published plays, poems, essays, memoirs, novels—has been translated into dozens of languages.

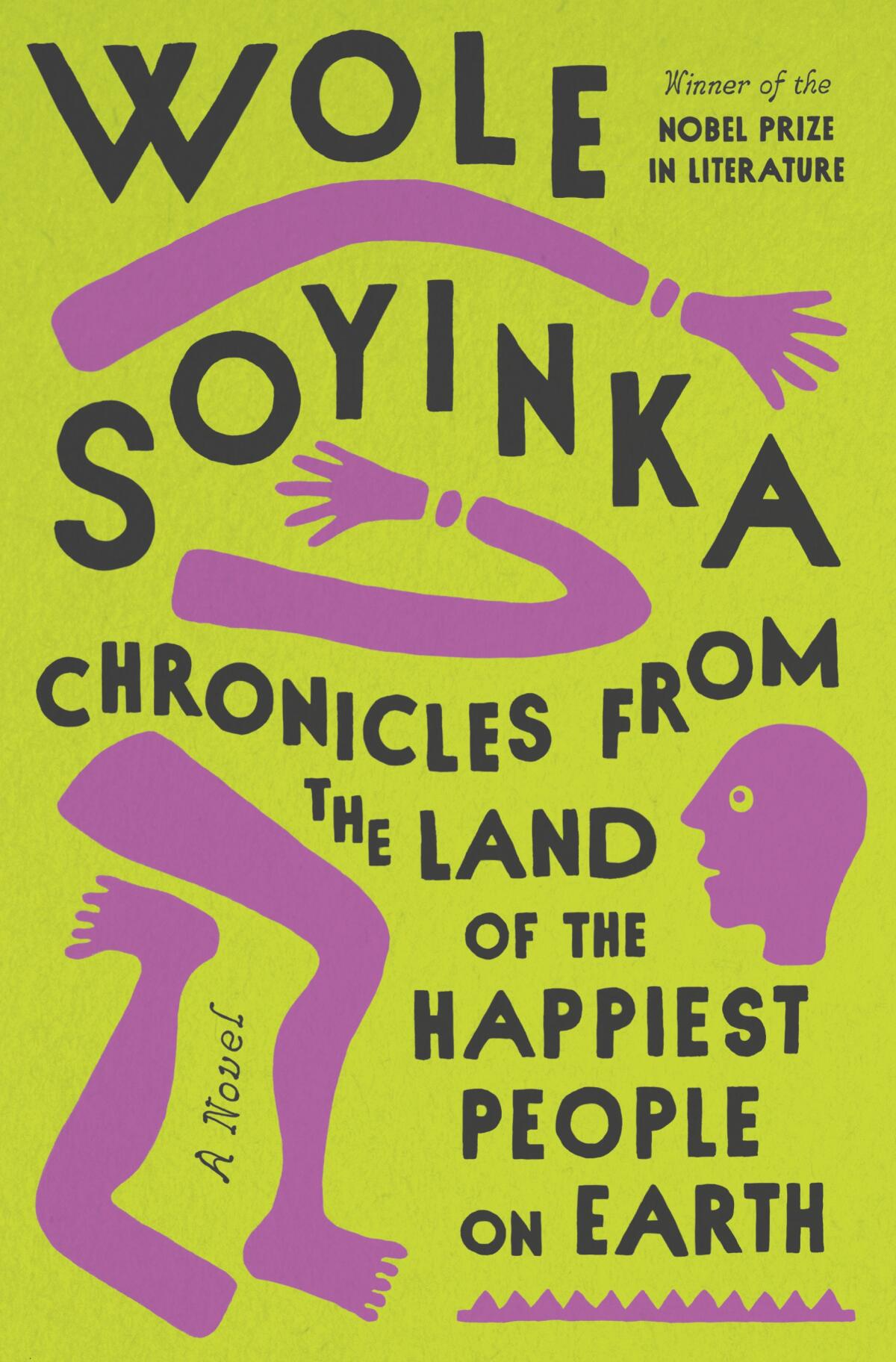

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is his third novel, and his first in nearly fifty years. Recently released in French by Editions du Seuil, it was originally published in English two years prior by Pantheon Books. Soyinka dedicates the novel to the memory of two of his compatriots and friends, the investigative journalist Dele Giwa, and governor and lawyer Bola Ige. Both were assassinated in their homeland. He recalls his friend Giwa having immediately showed up at Soyinka’s sister’s home where he was staying in Lagos, clutching a bottle of Cognac XO, basically in his pajamas, when the news of his Nobel was announced. Giwa was blown up by a package bomb that was sent to him days after this celebratory reunion. As for Bola Ige, a former attorney-general and lawyer, he was assassinated in 2001 at his home on the eve of his departure for the United States to take up his new job as Africa’s representative on the United Nations international law commission. His wife used to call Soyinka and her husband twins, because of the way they were involved in so many political activities together.

This close circle dedicated to the service of humanity reflects Soyinka’s remarkable life and restless persona. His uncle, Oludotun Ransome-Kuti (musician Fela Kuti’s father) ought to be mentioned here. Soyinka wanted to write his biography and through him write on that first generation of nationalists to which his Kuti belonged. That was to remain an unaccomplished project; his uncle died soon after, Nigeria got its independence in 1960, and he gave up the idea. What happened then? “Well, you know, when you are in prison you have a lot of time on your hands,” he tells me with sly amusement. Deprived of paper and pen by the prison directorate, he found a way to create his own writing material from whatever outlet he could—Soyinka playfully calls himself “Soy-Ink”—and he proceeded to write on cigarette papers, rolls of toilet paper, and in between the lines of a book he had managed to have smuggled in. He envisioned those scraps as the outline of the first chapter of what would have been his uncle’s biography, but they turned out to be the groundwork for his own moving memoir Ak é : The Years of Childhood , one of the best books of 1982 according to The New York Times Book Review .

We meet on a Friday, in the hall of his hotel, located on a quiet street by Saint-Germain-des-Près. It’s unusually hot in Paris for the season. He has a lunch appointment he wishes to get to and he says his voice is tired, brushing off any attempt to extend the interview. Wearing a Mao collar shirt and a dark blue sleeveless vest, he has on his right wrist a silver watch and a light tote bag is kept close-by. He momentarily looks for his hat, which he thinks he has left at an event he spoke at the night before, and makes the point that he wants it back.

“What keeps you young, what’s your secret?” I ask, right off the bat, to ease the mood.

“I have no idea,” he sighs. “I should be slowing down, I know, but each time I try to slow down something happens, and I have to get on the trail again. You see, I am deprived of that sense of inner tranquility once I turn my back on a situation. Quite frankly, I think it’s a flaw, because I am depriving myself of something which I know I need profoundly. If I didn’t manage to have some quiet in my mind, I’d have gone crazy years ago, so it’s a question of extracting myself [from the world] whenever I can.”

Soyinka calls this being a closet masochist. “It means depriving oneself of what one feels is pleasurable,” he explains. “You have to battle for your creative space, battle for it! Extract yourself whenever you can and be thankful for it, and just carry on waiting for the next opportunity to gratify your innermost instinct to disappear, and do not sacrifice it. If you can manage to balance the two [the activism and the writing] that’s OK, but if you find that you are being tortured internally then be quiet, just close the shop, run and go.”

His strong sense of social justice caused him a lifetime of pressure and persecution; yet he persevered. “I know it’s unbelievable but I really just prefer my peace of mind; I like to sink myself in a truly tranquil environment, which I find mostly in the forest. But [he raises his voice pronouncing those three letters], but, if between getting out of your house and getting into the forest you encounter something unacceptable on the way then that becomes a problem, and you cannot just enjoy what you really want until you have dealt with what you just saw.”

Puzzled, I query him whether that means he never intended to become a writer engagé . “No! Never!” he replies, without skipping a beat. “I don’t know,” he shrugs. “One shouldn’t expect literature to be committed. It is sufficient that a writer opens up possibilities. The fact is that something is being presented, a different view is presented, that’s what matters. The writer must be honest, if you have a bad temperament—of confrontation, of poking your finger in the eye of power—then by all means do so but if you do not don’t feel useless, don’t feel like you are betraying literature. You are writing, that’s your mission, that’s your m é tier ; exploit it in whatever direction it leads.”

The year is 1986: Wole Soyinka wins the Nobel Prize in Literature, and Elie Wiesel is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. What was the promise of the world then and what is its state today? Wars and displacement, corrupted systems and dictators, religious fundamentalism and brutality linger. “Take Gabon for instance [in late August, the army seized power disputing the election results in which Ali Bongo was declared winner; he had been president since 2009 and his father for 41 years before him], one family dynasty in power for fifty years, manipulating elections consistently, it was asking to be toppled, it deserves to be toppled—but—is the military the answer? The military has shown itself to be just as decadent, just as corrupt as the rest. Its claim to be a cleansing broom has been detonated, the only defense they have is to legitimize their terror. They will leave eventually, but look at the setback, it is heartbreaking.”

Soyinka’s art has always found its genesis in the African continent’s myths and mystifications, and in his own life experiences—he has been jailed on two occasions, in 1965 and again from 1967-1969, tortured, condemned to death by dictator Sani Abacha, and forced repeatedly and for long periods into hiding for his own safety. What can literature do in the face of such chaos, injustice, and violence? “Well,” he says in a hoarse voice, “present a model of possibilities, and that is all. Beyond that, nothing. The fact that literature is not helpless is proven by the fact that it attracts power. Those who hold power use it to censor, to harass [writers] so literature is not as helpless or insignificant as some people think.”

We turn to the subject of his incarceration: how does prison change a man? “When I came out, I was very bitter, not bitter about being in prison, I was bitter about the treatment I received, but most importantly of all the statements that were attributed to me which were false. My immediate writing was bitter, then I settled on looking at society and looking at the human condition and creating microworlds which is what all writers do. One of the problems one has as a writer who writes about society is the danger of becoming pessimistic, resentful, and aggressively so.”

The immediate writing he refers to is Madmen and Specialists , a play about the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), considered the writer’s darkest dramatic work. He recounted his years behind bars in 1972’s The Man Died: Prison Notes , which the Nigerian government eventually banned in 1984. His play Death and the King ’ s Horseman , first performed in 1976, brings Soyinka worldwide acclaim.

Wole Soyinka does not regard himself as a novelist; he refers to his novels as “accidents.” His debut, The Interpreters , was published in 1965, followed by Season of Anomy in 1973. He swears that this one, his third, is his last. “Oh, I am not going that way again! I just know it intuitively. A novel is hard labor. A play is unfinished and on stage it gets finished, so you don’t really mind, because you know that on stage you will have an opportunity to change things here and there. Theater is a dynamic process. A novel is frozen, until maybe a filmmaker is foolish enough to attempt to put it on celluloid.”

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is set in an imaginary Nigeria and examines the unreasonable and unethical contemporary state of affairs there. In the US, it has been received by some as pessimistic, while others, particularly in Europe, have welcomed it as political satire. “Although it’s not for me to decide, some say it’s also a Whodunit, and I say: absolutely, why not? I love detective stories, I used to eat them up in my youth, and I always said, one of these days I will write a detective story.” He laughs. “It wasn’t my intent at the start, but along the writing process it came to me that I could tag on a mystery element.”

Soyinka can create a story out of anything and he can write anywhere, but distance can help. “I had to get out of Nigeria to write [ Chronicles ]. I had to wait year after year to feel completely detached from the physical environment I was writing about. I wrote some parts of it in Senegal and in Ghana. Then Covid happened, it was touch and go, and the world began to button down. I was in Los Angeles at my son’s wedding; it was the last social event for us as a family, people had come from all over. When I realized that the lockdown was fast approaching I knew I had to go back to Nigeria, which is the only home I consider home. So I said: Listen, I’m getting on that plane, the rest of you, wherever you are locked-down, good luck to you. I couldn’t get back into Lagos directly, I had to go to Ghana and then continue by road, but I made sure I arrived in the nick of time to Abeokuta. And that’s where I finished Chronicles .”

When Soyinka is not keen on something he makes sure the message gets through loud and clear. In 2016, after the election of Donald Trump as the 46th President, he destroyed his U.S. Green Card. That same year, the Nobel committee’s literary laureate was Bob Dylan, “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Wole Soyinka’s discontent vibrates the room. “The prize for literature should have never gone that way!” he tells me, his fingers fidgeting in the air. “As a music lover, and a composer myself, I respect music, but there is something called literature, and we don’t have enough prizes as is. If they award this prize to one more musician, I am sending all my musical compositions to the Grammys. I know what I consider literature, and writing lyrics or certain songs, is not literature, it is music! You want to have a Nobel Prize for music, fine, I’ll be there, but don’t say that you are taking a prize away from this discipline and extending it to another!”

On that note, he grows impatient. He has an appointment, which means I have one last question: What has the Nobel meant for his life? “It has changed nothing at all for me. All it has done for me is that since then I have to fight for my anonymity.”

Wole Soyinka leaves not a minute later. It’s sunny out. And his hat is still missing.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Aysegul Sert

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Masha Gessen and Nathan Thrall on The Whole Story of Israel and Palestine

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Wole soyinka (1934- ).

Akinwande Ouwole “Wole” Soyinka, the first African writer to win a Nobel Prize in Literature (1986) was born in Abeokuta, Nigeria on July 13, 1934. His father, Canon S.A. Soyinka, was an Anglican minister and his mother, Grace Eniola, was the daughter of an Anglican minister.

Soyinka received a primary school education in Abeokuta and then completed secondary school at Government College, Ibadan . He attended the University of Ibadan for two years (1952-1954) before completing his undergraduate education at the University of Leeds in England in 1957. Soyinka received his degree in drama at Leeds under the instruction of world-renowned Shakespearean critic G. Wilson Knight. He worked briefly as a play reader at the Royal Court Theater in London before returning to Nigeria to study African drama. Soyinka taught at the University of Lagos, the University of Ibadan, and the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. On the faculty at the latter institution since 1975, he is currently a Professor of Comparative Literature.

Soyinka wrote his first major plays, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel, while working at the Royal Court Theater in London. His next plays, The Trials of Brother Jero and A Dance of the Forest appeared after he returned to Nigeria in 1960. A Dance of the Forest , a biting criticism of Nigeria’s elites, was first performed on October 1, 1960, Nigeria’s Independence Day. In 1963, Soyinka’s first feature length film, Culture in Transition , was released. One year later, The Interpreters , his most famous novel, was published in London. Both pursued a similar theme.

By 1965, Soyinka’s reputation as a leading dramatist and a political critic of the government was well established. That year Soyinka was arrested for his criticism of recent elections but was released after protests from the international community. In 1967, he secretly and unofficially met with Ibo leaders in a vain attempt to prevent the Nigerian Civil War . When the war began Soyinka was declared a traitor and was incarcerated for the remainder of the war.

After his release, Soyinka lectured and lived in Europe. By 1975, he had returned to Africa and lived briefly in Accra , Ghana, where he edited a literary magazine called Transition . He used the magazine to critique African dictators such as Idi Amin in Uganda. He returned to Nigeria later that year after his political nemesis, General Yakubu Gowon , was removed from power. For the next decade he continued his writing and political protests prompting more government repression. His 1984 play, The Man Died , was banned by a Nigerian court. In 1986, however, Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In November 1994 Soyinka fled Nigeria and briefly lived in exile in the United States. In 1996, while in the U.S., he wrote The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis . The following year, he was charged with treason by the Nigerian military government. Soyinka returned to Nigeria when civilian rule was restored in 1999. However, his critique of the government continues. In April 2007, he called for the cancellation of Nigerian elections due to widespread violence and fraud.

In a career that has lasted more than five decades, Soyinka has written twenty-one plays, eight books of poetry, five books of essays, two novels, and five memoirs. He has also produced two feature-length films. Wole Soyinka lives in Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Biodun Jeyifo, Wole Soyinka: Politics, Poetics and Post Colonialism (New York: Cambridge Press, 2004); http://prelectur.stanford.edu/lecturers/soyinka/ .

About Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka is a world-renowned writer, rights activist, polemicist and Nobel Prize Laureate. With a career spanning more than six decades, Soyinka is widely regarded as one of the most important literary figures of the twentieth century, and his works have had a significant impact on African and world literature.

- Biography 1

- Biography 2

- Biography 3

- Achievements

by Poetry Foundation

Nigerian playwright and political activist Wole Soyinka received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986. He was born in 1934 in Abeokuta, near Ibadan, into a Yoruba family and studied at University College in Ibadan, Nigeria, and the University of Leeds, England. Soyinka, who writes in English, is the author of five memoirs, including Aké: the Years of Childhood (1981) and You Must Set Forth at Dawn: A Memoir (2006), the novels The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anomy (1973), and 19 plays shaped by a diverse range of influences, including avant-garde traditions, politics, and African myth.

Soyinka’s poetry similarly draws on Yoruba myths, his life as an exile and in prison, and politics. His collections of poetry include Idanre and Other Poems (1967), Poems from Prison (1969, republished as A Shuttle in the Crypt in 1972), Ogun Abibiman (1976), Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988), and Selected Poems (2001).

An outspoken opponent of oppression and tyranny worldwide and a critic of the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka has lived in exile on several occasions. During the Nigerian civil war in the 1960s, he was held as a prisoner in solitary confinement after being charged with conspiring with the Biafrans. In 1997, while in exile, he was tried for, convicted of, and sentenced to death for antimilitary activities, a sentence that was later lifted.

Soyinka has taught at a number of universities worldwide, among them Ife University, Cambridge University, Yale University, and Emory University.

by Biography

Who Is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka was born in Nigeria and educated in England. In 1986, the playwright and political activist became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. He dedicated his Nobel acceptance speech to Nelson Mandela . Soyinka has published hundreds of works, including drama, novels, essays and poetry, and colleges all over the world seek him out as a visiting professor.

Wole Soyinka was born Akinwande Oluwole “Wole” Babatunde Soyinka on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, near Ibadan in western Nigeria. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a prominent Anglican minister and headmaster. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, who was called “Wild Christian,” was a shopkeeper and local activist. As a child, he lived in an Anglican mission compound, learning the Christian teachings of his parents, as well as the Yoruba spiritualism and tribal customs of his grandfather. A precocious and inquisitive child, Wole prompted the adults in his life to warn one another: “He will kill you with his questions.”

After finishing preparatory university studies in 1954 at Government College in Ibadan, Soyinka moved to England and continued his education at the University of Leeds, where he served as the editor of the school’s magazine, The Eagle . He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1958. (In 1972 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate).

Plays & Political Activism

In the late 1950s Soyinka wrote his first important play, A Dance of the Forests , which satirized the Nigerian political elite. From 1958 to 1959, Soyinka was a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. In 1960, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship and returned to Nigeria to study African drama.

“The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism.”

Soyinka is also a political activist, and during the civil war in Nigeria he appealed in an article for a cease-fire. He was arrested for this in 1967, and held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969.

Nobel Prize and Later Career

In 1986, upon awarding Soyinka with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the committee said the playwright “in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” Soyinka sometimes writes of modern West Africa in a satirical style, but his serious intent and his belief in the evils inherent in the exercise of power are usually present in his work. To date, Soyinka has published hundreds of works.

In addition to drama and poetry, he has written two novels, The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anom y (1973), as well as autobiographical works including The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), a gripping account of his prison experience, and Aké ( 1981), a memoir about his childhood. Myth, Literature and the African World (1975) is a collection of Soyinka’s literary essays.

“Against my rational instincts, I believe that we have here a genuine case of a born-again democrat,” he said. Ultimately, “the real heroes of this exercise have been the Nigerian people and that gingers me up.”

Now considered Nigeria’s foremost man of letters, Soyinka is still politically active and spent the 2015 election day in Africa’s biggest democracy working the phones to monitor reports of voting irregularities, technical issues and violence, according to The Guardian . After the election on March 28, 2015, he said that Nigerians must show a Nelson Mandela–like ability to forgive president-elect Muhammadu Buhari’s past as an iron-fisted military ruler, according to Bloomberg.com .

Personal Life

Soyinka has been married three times. He married British writer Barbara Dixon in 1958; Olaide Idowu, a Nigerian librarian, in 1963; and Folake Doherty, his current wife, in 1989. In 2014, Soyinka revealed he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and cured 10 months after treatment.

by Academy of Achievement

Writing became a therapy. I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance.

Akonwande Oluwole “Wole” Soyinka was born in Abeokuta in Western Nigeria. At the time, Nigeria was a Dominion of the British Empire. British religious, political and educational institutions co-existed with the traditional civil and religious authorities of the indigenous peoples, including Soyinka’s ethnic group, the Yorùbá people, who predominate in Western Nigeria. As a child, Soyinka lived in an Anglican Christian enclave known as the Parsonage. Soyinka’s mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was a devout Anglican; in his memoirs, Wole Soyinka calls his mother “Wild Christian.” His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was headmaster of the parsonage primary school, St. Peter’s. Known as “S.A.,” Wole Soyinka calls him “Essay” in his memoirs. Although the Soyinka family had deep ties to the Anglican Church, they enjoyed close relations with Muslim neighbors, and through his extended family — particularly his father’s relations — Wole Soyinka gained an early acquaintance with the indigenous spiritual traditions of the Yorùbá people. Even among practicing Christians, belief in ghosts and spirits was common. The young Wole Soyinka enjoyed participating in Anglican services and singing in the church choir, but he also formed an early identification with Ogun, the Yorùbá deity associated with war, iron, roads and poetry.

Soyinka’s mother, a shopkeeper, joined a protest movement, led by her sister Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, against the traditional ruler, the Alake of Abeokuta, who ruled with the support of the British colonial authorities. When the Alake levied oppressive taxes against the shopkeepers, Mrs. Ransome-Kuti, Mrs. Soyinka, and their followers refused to pay, and the Alake was forced to abdicate.

Thanks to his father, young Wole Soyinka enjoyed access to books, not only the Bible and English literature but to classical Greek tragedies such as the Medea of Euripides, which had a profound effect on his imagination. A precocious reader, he soon sensed a link between the Yorùbá folklore of his neighbors and the Greek mythology underlying so much of western literature.

He moved quickly from St. Peter’s Primary School to the Abeokuta Grammar School and won a scholarship to the colony’s premier secondary school, the Government College in Ibadan. At this boarding school, he continued to distinguish himself in his studies, writing stories and acting in school plays, the beginning of his lifelong preoccupation with the practical aspects of theatrical performance.

After graduation at age 16 from the Government College, Soyinka deferred immediate admission to university life and moved to the colonial capital, Lagos, to work in an uncle’s pharmacy for two years before entering university. During this period of personal independence, he began writing plays for local radio. In 1950, he entered the University at Ibadan. Two years later, won a scholarship to the University of Leeds in England, and left Africa for the first time.

In England, he joined a close-knit community of West African students. The petty racism they encountered in Britain seemed less important than the reports they read from South Africa of black Africans being subjected to legally enforced racial discrimination in their own country by the white-led apartheid government. Along with his fellow African students, Soyinka imagined a pan-African movement to liberate South Africa. He went so far as to enlist in the British program of student military education, in hopes that he could use this training in a future campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa. He dropped out of the program during the Suez Crisis, when it appeared that students might be called up to serve in Egypt. As Britain prepared to leave Nigeria, students like Soyinka were excused from further military service.

After graduating from the University of Leeds, Wole Soyinka continued to study for a master’s degree while writing plays drawing on his Yorùbá heritage. His first major works, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel , date from this period. In 1958, The Lion and the Jewel was accepted for production by the Royal Court Theatre in London. Beginning in the late 1950s, the Royal Court was the major venue for serious new drama in Britain. Soyinka interrupted his graduate studies to join the theater’s literary staff. From this post, he was able to watch the rehearsal and development process of new plays at a time when the British theater was entering a period of renewed vitality. His own next major work was The Trials of Brother Jero , expressing his skepticism about the self-styled elite of black Nigerians who were preparing to take power from the British colonial regime.

In 1960, Soyinka received a Rockefeller Foundation grant to research traditional performance practices in Africa. Nigeria was poised to become independent from Britain, and Soyinka’s play A Dance of the Forest, another satire of the colonial elite, was chosen to be performed during the independence festivities. Soyinka joined the English faculty at the University of Ibadan. He also formed a theater company, 1960 Masks, to produce topical plays, employing traditional performance techniques to dramatize the many issues arising from Nigerian independence. His writings, including his 1964 novel, The Interpreters , were bringing him fame outside his own country, but he faced increasing difficulties with censorship inside Nigeria. Independence from Britain had not brought about the open democratic society Soyinka and others had hoped for. In negotiating the independence of the country, Britain had overestimated the population of the northern region, dominated by Hausa-Fulani people of Muslim faith, and given them greater representation in the national parliament, at the expense of the predominantly Christian peoples of the southern regions: the Yorùbá in the West and the Igbo in the East.

In Western Nigeria, the results of a 1964 regional election were set aside so that a candidate favored by the central government could claim victory. With some friends, Soyinka forced his way into the local radio station and substituted a tape of his own for the recorded message prepared by the fraudulent victor of the election. This escapade caused his arrest and detention for two months, but international publicity led to his acquittal. Following his release, Soyinka was appointed to the English Department of Lagos University, and completed the comedy Kongi’s Harvest , which would be produced throughout the English-speaking world. Soyinka had become one of the best-known writers in Africa, but political developments would soon thrust him into a more difficult role. The discovery of oil in the Southeast in 1965 further heightened ethnic and regional tensions in Nigeria. A 1966 military coup led by Igbo officers was followed by a counter-coup, which installed the young army officer Yakubu Gowon as head of state. Massacres of Igbo living in the North sent more than a million refugees fleeing south, and many Igbo began to call for secession from Nigeria. Hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Soyinka traveled in secret to meet with the secessionist General Ojukwu and urged a peaceful resolution. When Ojukwu and the Eastern forces declared an independent Republic of Biafra, Soyinka contacted General Obasanjo of the Western forces to urge a negotiated settlement of the conflict, but Obasanjo sided with the national government, and a full-scale civil war ensued. Soyinka’s friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, joined the Biafran forces and was killed in action.

Soyinka was accused of collaborating with the Biafrans and went into hiding. Captured by Nigerian federal troops, he was imprisoned for the rest of the war. From his prison cell, he wrote a letter asserting his innocence and protesting his unlawful detention. When the letter appeared in the foreign press, he was placed in solitary confinement for 22 months. Despite being denied access to pen and paper, Soyinka managed to improvise writing materials and continued to smuggle his writings to the outside world. A volume of verse, Idanre and Other Poems , composed before the war, was published to international acclaim during his imprisonment. By the end of 1969, the war was virtually over. Gowon and the Nigerian federal army had defeated the Biafran insurgency, an amnesty was declared, and Soyinka was released. Unable to return immediately to his old life, he repaired to a friend’s farm in the South of France. While recuperating, he wrote an adaptation of the classical Greek tragedy The Bacchae by Euripides. Across the millennia, the story of a state destroyed by a sudden eruption of senseless violence had acquired a special resonance for Soyinka. Another volume of verse, Poems from Prison , also known as A Shuttle in the Crypt , was published in London.

Soyinka returned to Nigeria to head the Department of Theater Arts at the University of Ibadan. The 1970s were a productive decade for Wole Soyinka. He oversaw stage and film productions of his play Kongi’s Harvest and wrote one of his most compelling satirical plays, Madmen and Specialists . His prison memoir, The Man Died , was published in 1972, followed by a novel, The Season of Anomy . He traveled to France and the United States for productions of his plays. When political tensions resurfaced, unresolved by the civil war, Soyinka resigned his university post and went to live in Europe, lecturing at Cambridge and other universities. Oxford University Press published his Collected Plays in 1974. One of his greatest works appeared the following year, the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman . After a number of years in Europe, Soyinka settled for a time in Accra, Ghana, where he edited the literary journal Transition . His column in the magazine became a forum for his continued commentary on African politics, in particular for his denunciation of dictatorships such as that of Idi Amin in Uganda.

In 1975, General Gowon was deposed, and Soyinka felt confident enough to return to Nigeria, where he became Professor of Comparative Literature and head of the Department of Dramatic Arts at the University of Ife. He published a new poetry collection, Ogun Abibiman , and a collection of essays, Myth, Literature and the African World , a comparative study of the roles of mythology and spirituality in the literary cultures of Africa and Europe. His continuing interest in international drama was reflected in a new work, inspired by John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera . Soyinka called his musical allegory of crime and political corruption Opera Wonyosi . He created a new theatrical troupe, the Guerilla Unit, to perform improvised plays on topical themes.

At the turn of the decade, Wole Soyinka’s creativity was expanding in all directions. In 1981, he published the first of several volumes of autobiography, Aké: The Years of Childhood . In the early 1980s, he wrote two of his best-known plays, Requiem for a Futurologist and A Play of Giants , satirizing the new dictators of Africa. In 1984, he also directed the film Blues for a Prodigal . For years, Soyinka had written songs. In the 1980s, Nigerian music, including that of Soyinka’s cousin, the flamboyant bandleader Fela Ransome-Kuti, was capturing the attention of listeners around the world. In 1984, Soyinka released an album of his own music entitled I Love My Country , with an assembly of musicians he called The Unlimited Liability Company.

Soyinka also played a prominent role in Nigerian civil society. As a faculty member at the University of Ife, he led a campaign for road safety, organizing a civilian traffic authority to reduce the shocking rate of traffic fatalities on the public highways. His program became a model of traffic safety for other states in Nigeria, but events soon brought him into conflict with the national authorities. The elected government of President Shehu Shagari, which Soyinka and others regarded as corrupt and incompetent, was overthrown by the military, and General Muhammadu Buhari became Head of State. In an ominous sign, Soyinka’s prison memoir, A Man Died, was banned from publication.

Despite troubles at home, Soyinka’s reputation in the outside world had never been greater. In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first African author to be so honored. The Swedish Academy cited the “sparkling vitality” and “moral stature” of his work and praised him as one “who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” When Soyinka received his award from the King of Sweden in the ceremony in Stockholm, he took the opportunity to focus the world’s attention on the continuing injustice of white rule in South Africa. Rather than dwelling on his own work, or the difficulties of his own country, he dedicated his prize to the imprisoned South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. His next book of verse was called Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems . He followed this with two more plays, From Zia with Love and The Beatification of Area Boy , along with a second collection of essays, Art, Dialogue and Outrage . He continued his autobiography with Isara: A Voyage Around Essay , centering on his memories of his father S.A. “Essay” Soyinka, and Ibadan, The Penkelemes Years .

Meanwhile, Soyinka continued his criticism of the military dictatorship in Nigeria. In 1994, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named Wole Soyinka a Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of African culture, human rights and freedom of expression. Less than a month later, a new military dictator, General Sani Abacha, suspended nearly all civil liberties. Soyinka escaped through Benin and fled to the United States. Soyinka judged Abacha to be the worst of the dictators who had imposed themselves on Nigeria since independence. He was particularly outraged at Abacha’s execution of the author Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was hanged in 1995 after a trial condemned by the outside world. In 1996, Soyinka published The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Memoir of the Nigerian Crisis . Predictably, the work was banned in Nigeria, and in 1997, the Abacha government formally charged Wole Soyinka with treason. General Abacha died the following year, and the treason charges were dropped by his successors.Since 1994, Wole Soyinka has resided primarily in the United States. He has taught at a number of American universities, including Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles. Since moving to the United States, he has written another play, King Baabu , a volume of verse, Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known , and his latest book of memoirs, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006).

Although Wole Soyinka has always been reticent about discussing his family life, in this volume he makes a particularly touching dedication to his “stoically resigned” children, and to his wife Adefolake, for enduring many years of hardship and dislocation.

Although presidential elections were held in Nigeria in 2007, Soyinka denounced them as illegitimate due to ballot fraud and widespread violence on election day. Wole Soyinka continues to write and remains an uncompromising critic of corruption and oppression wherever he finds them.

Human life has meaning only to that degree and as long as it is lived in the service of humanity.

I don’t know any other way to live but to wake up every day armed with my convictions, not yielding them to the threat of danger and to the power and force of people who might despise me.

Looking at faces of people, one gets the feeling there's a lot of work to be done.

A tiger doesn't proclaim his tigritude, he pounces.

Achievements & Awards

| Year | Achievement/Award | Awarded by |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Honorary D.Litt. | University of Leeds |

| 1974 | Overseas Fellow | Churchill College, Cambridge |

| 1983 | Honorary Fellow | Royal Society of Literature |

| 1983 | Anisfield-Wolf Book Award | Cleveland Foundation |

| 1986 | Nobel Prize for Literature | Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, Sweden |

| 1986 | Agip Prize for Literature | |

| 1986 | Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (CFR) | Federal Republic of Nigeria |

| 1990 | Benson Medal | Royal Society of Literature |

| 1993 | Honorary doctorate | Harvard University |

| 1994 | UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture, human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication. | UNESCO |

| 2002 | Honorary fellowship | SOAS |

| 2005 | Honorary doctorate degree | Princeton University |

| 2005 | Akinlatun of Egbaland | The Oba Alake of the Egba clan of Yorubaland |

| 2009 | Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement | American Academy of Achievement |

| 2013 | Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, Lifetime Achievement | Cleveland Foundation |

| 2014 | International Humanist Award | IHEU World Humanist Congress |

| 2017 | Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Humanities | University of Johannesburg, South Africa |

| 2017 | "Special Prize" of the Europe Theatre Prize (Premio Europa per il Teatro) | European Commission |

| 2018 | University of Ibadan renamed its arts theater to Wole Soyinka Theatre | University of Ibadan |

| 2018 | Honorary Doctorate Degree of Letters | Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB) |

| 2022 | Honorary Degree | Cambridge University |

| 2015 | Nominated for Special NAFCA Literary Arts Award | NAFCA |

| 2015 | Candidate for the position of Oxford professor of poetry | Oxford University |

Literary Work

- Keffi’s Birthday Treat (1954)

- The Invention (1957)

- Childe Internationale (1957)

- The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

- A Quality of Violence (1959)

- The Lion and the Jewel (1959)

- The Trials of Brother Jero (1960)

- A Dance of the Forests (1960)

- My Father’s Burden (1960)

- The Strong Breed (1964)

- Before the Blackout (1964)

- Kongi’s Harvest (1964)

- The Road (1965)

- Madmen and Specialists (1970)

- The Bacchae of Euripides (1973)

- Camwood on the Leaves (1973)

- Jero’s Metamorphosis (1973)

- Death and the King’s Horseman (1975)

- Opera Wonyosi (1977)

- Requiem for a Futurologist (1983)

- A Play of Giants (1984)

- From Zia, with Love (1992)

- The Detainee (radio play)

- A Scourge of Hyacinths (radio play)

- The Beatification of Area Boy (1996)

- Document of Identity (radio play, 1999)

- King Baabu (2001)

- Etiki Revu Wetin (1983)

- Alapata Apata (2011)

- “Thus Spake Orunmila” (in Sixty-Six Books (2011)

- “Towards a True Theater” (1962)

- Culture in Transition (1963)

- Neo-Tarzanism: The Poetics of Pseudo-Transition

- Art, Dialogue, and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988)

- From Drama and the African World View (1976)

- Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976)

- The Blackman and the Veil (1990)

- The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996)

- The Burden of Memory – The Muse of Forgiveness (1999)

- A Climate of Fear (the BBC Reith Lectures 2004, audio and transcripts)

- New Imperialism (2009)

- Of Africa (2012)

- Harmattan Haze On An African Spring (2012)

- Of Power and Freedom – Vol 1 (2022)

- Of Power and Freedom – Vol 2 (2022)

- Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions (2019)

- The Interpreters (1965)

- Season of Anomy (1973)

- Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (2021)

Short stories

- A Tale of Two (1958)

- Egbe’s Sworn Enemy (1960)

- Madame Etienne’s Establishment (1960)

- Kongi’s Harvest

- Culture in Transition

- Blues for a Prodigal

Poem Collections

- Telephone Conversation (1963) (appeared in Modern Poetry in Africa)

- Idanre and other poems (1967)

- A Big Airplane Crashed into The Earth (original title Poems from Prison) (1969)

- A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971)

- Ogun Abibiman (1976)

- Mandela’s Earth and other poems (1988)

- Early Poems (1997)

- Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known (2002)

- The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972)

- Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981)

- Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years: a memoir 1945–1965 (1989)

- Ìsarà: A Voyage around Essay (1989)

- You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006)

Translations

- The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga (1968; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmalẹ̀)

- In the Forest of Olodumare (2010; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Igbo Olodumare)

Insert/edit link

Enter the destination URL

Or link to existing content

Poems & Poets

Wole Soyinka

Nigerian playwright and political activist Wole Soyinka received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986. He was born in 1934 in Abeokuta, near Ibadan, into a Yoruba family and studied at University College in Ibadan, Nigeria, and the University of Leeds, England. Soyinka, who writes in English, is the author of five memoirs, including Aké: the Years of Childhood (1981) and You Must Set Forth at Dawn: A Memoir (2006), the novels The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anomy (1973), and 19 plays shaped by a diverse range of influences, including avant-garde traditions, politics, and African myth. Soyinka’s poetry similarly draws on Yoruba myths, his life as an exile and in prison, and politics. His collections of poetry include Idanre and Other Poems (1967), Poems from Prison (1969, republished as A Shuttle in the Crypt in 1972), Ogun Abibiman (1976), Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988), and Selected Poems (2001). An outspoken opponent of oppression and tyranny worldwide and a critic of the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka has lived in exile on several occasions. During the Nigerian civil war in the 1960s, he was held as a prisoner in solitary confinement after being charged with conspiring with the Biafrans. In 1997, while in exile, he was tried for, convicted of, and sentenced to death for antimilitary activities, a sentence that was later lifted. Soyinka has taught at a number of universities worldwide, among them Ife University, Cambridge University, Yale University, and Emory University.

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

Wole soyinka, nobel prize in literature.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

Wole Soyinka summary

Wole Soyinka , in full Akinwande Oluwole Soyinka , (born July 13, 1934, Abeokuta, Nigeria), Nigerian playwright. After studying in Leeds, Eng., he returned to Nigeria to edit literary journals, teach drama and literature at the university level, and found two theatre companies. His plays, written in English and drawing on West African folk traditions, often focus on the tensions between tradition and progress. Symbolism, flashback, and ingenious plotting contribute to a rich dramatic structure. His serious plays reveal his disillusionment with African authoritarian leadership and with Nigerian society as a whole. His works include A Dance of the Forests (1960), The Lion and the Jewel (1963), Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), and From Zia, with Love (1992). He has written several volumes of poetry; his best-known novel is The Interpreters (1965). A champion of Nigerian democracy, he was repeatedly jailed and exiled. In 1986 he became the first black African to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka Discusses His First Novel in Nearly Fifty Years

In 1965, five years after Nigeria had gained its independence, the playwright Wole Soyinka was already known as an opposition figure. Authorities falsely accused him of armed robbery, and, before the country’s civil war, in the late sixties, Soyinka tried to avert fighting. He was accused of conspiring with rebels and imprisoned by the Nigerian government. He’s a writer with an astonishing history of putting himself on the line for his political and social commitments.

Soyinka has received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He has written more than two dozen plays, a vast amount of poetry, several memoirs, essays, and short stories, and just two novels. His third novel is out now, nearly five decades after the last one. Called “ Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth ,” it’s both a political satire and a murder mystery. It involves four friends, a secret society dealing in human body parts, and more corruption than any one country can bear. The staff writer Vinson Cunningham spoke with Soyinka at his home in Nigeria.

I really want to talk to you about “Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth,” a title that I love. I heard that you’ve been thinking about this story for many years now. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

It’s been a little bit overwhelming, I think. I wasn’t expecting the standard reception of it. I mean, it’s just part of my own creative continuum, in a different format—you know, like taking time off from theatre to write a novel.

This is your third novel, and, of course, you’re known most prolifically for your works of theatre. But what is it that the novel does for you that theatre doesn’t? This change in form—are there necessities that it meets that theatre doesn’t, and vice versa? What’s the form about for you?

What the novel does for me as a medium of expression is to assuage the masochist in me, because the novel is very taxing—taxing in the sense that it’s tempting to go in so many directions. Theatre, for me, is more focussed. When you’re a narrator, you’re juggling a number of characters, and they insist on wandering very willfully in directions which you did not preview, you know? And then you forget where you last saw them, and so on. I really praise novelists, those whose métier is a novel. I have a hard time at it.

You offer us this total panoply of great characters. There’s a crooked religious leader. There are politicians, a sort of earnest diplomat, a famous doctor. Did you, in the course of writing this book—was there a favorite character that you alighted on? Was there one who was especially willful and sort of surprised you in different ways?

There’s no question at all that a number of the characters were “inspired” or “triggered” into being by personal encounters. I took great pains to insure that some of the villains knew that they provided the base material—and, in fact, I’ve even met one of them since the novel came out. He came up to me and I said, “Well, you’re coming to me. I hope you realize that you were this in the novel.” It was a politician and, like a good politician, he said, “Oh, Prof, that’s O.K. But I really want to discuss a certain issue with you in the novel. Forget that character.” So the novel does give one that latitude, I must confess, and then you can play variations, far more than in theatre. I think theatre is almost pre-written. By that I mean they are more constricted in the case of the theatre, and that is one of the reasons why tackling a theme like this human tumult in which I’ve been existing, watching others survive—me, too, surviving in my own way, watching that deterioration of society—the novel intuitively struck me as the only medium in which I could actually purge myself of this oppressive sense of society going haywire.

It’s interesting: there is this sense, this dark sense, of, as you say, a society going haywire, and it’s contrasted against this wonderful title, “The Land of the Happiest People on Earth.” Now, I heard that this was inspired by the “ World Happiness Report ,” where Nigeria was rated one of the happiest countries in the world. First of all, is that true? And what did that reality present to you artistically?

Well, when I saw that world report, I thought, Look at these people laughing at us. Why are they so cruel? Why are they doing this? And then I realized it was supposed to be a serious poll, a serious estimate. It was supposed to be objective, analytical, even scientific. And so I looked into this—I said, Maybe I’m in the wrong place, but when I looked around it was still a society which I recognize as my own, as the one in which I function. So it stuck in my head for quite a while. This was some years ago. And, when I began working on it, it actually began with other titles. Eventually, I slowly realized, Oh, wait a minute. That estimation, that analysis, is the exact title I’ve been looking for.

You know, happiness is such a fraught idea. Here in America, of course, we’ve sort of encoded it into our national myth—you know, the “pursuit of happiness.” What does it mean for you? Because, of course, it can be totally vapid, fun-seeking, surface—sort of epicureanism, I guess. But it can also speak to a real joy. What does it mean for you, and why did it fit so well?

It fits so well, of course, because it’s an irony. This country—people in this nation are not the happiest, by no strength of the imagination, and yet, at the same time, if they went deep enough in society, I think they would flee, or consign this nation to the place to be during your—what’s that season of yours, when you hang skeletons all over the place?

Halloween. [ Laughs. ]

Exactly, Halloween. Maybe this is Halloween nation, and they’re not going to understand it. But then, again, as I was saying, you do encounter those who extract, forcibly, a measure of contentment or fulfillment, even of the most meagre kind. They are buoyed either by religion or by an ingrained traditional philosophy that the worst is yet to come, and therefore you’d better enjoy the present. Because Nigerians do celebrate—I mean, that is not a lie. People all over the world where Nigerians are, they do salute Nigerians for their spirit of celebration, which is why I took pains to insure that at least one character represented what the pursuit of happiness might be—through creativity, through just love of others, through just making others happy, if only for a few moments. So it’s a mishmash of ironies, of acknowledgements, of concession, of even a measure of salute to the people. I hope that measure comes out, that element comes out.

Speaking of this issue of happiness and the different places where it can be found, or not found, you know—where it can be promised but not delivered, perhaps—one of those is religion. And a lot of this book turns on a kind of an upswing in religious fundamentalism. Is it O.K. if I read a very short passage that I just love from this book? It’s about a preacher who we get to know better later on, and his name is Papa Divina, and he has this epiphany. He’s on this kind of long comic journey across West Africa. We see him in Liberia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and he’s in Ghana, and he has this epiphany. He’s just kind of made this pun on the idea of a site of prophecy: a “prophesite.” And he says this:

He looked nervously around, hoping that no one else had caught that creative slip, or at least that it had not registered with anyone in that audience with apostolic ambitions. The flash momentarily unnerved him, as it inserted profound doubts in his mind––could it be that he was after all the genuine article? That he had indeed responded to an authentic call to prophecy? Prophesite! Why had all his predecessors failed to formulate such an exquisite, indeed mellifluous name for a place of spiritual quest? Could it be that he was, unbeknownst to himself till now, truly . . . called?

This person, who’s clearly a charlatan of a kind but almost convinces himself that he’s not, in certain ways: I wanted to talk to you just about this emphasis on fundamentalism. What role did that play for you?

You know, some of the greatest charlatans of religion, of the religious profession, are really very likable people, very lovable people. First of all, they’re performers. They enjoy performing. Now, if you enjoy what you’re doing, you’re a happy person, and you infect others with some of that happiness. So even while you are, you know, blabbering platitudes, knowing very well that you are conning your congregation, you do produce not just happiness; sometimes rapture—genuine, authentic rapture. And so I find them very complex people, the genuine religionists. Of course, some of them are just sinister—the fundamentalists, for instance, both of Christianity and of Islam. And Hinduism, for instance. All religions have their fundamentalist sectors, and those are really sinister, dangerous people. They have no sense of humor. They cannot see the pathetic side of life. They cannot even look at themselves in the mirror—and I give them a sort of pat on the back and say, “You charlatan, but today wasn’t bad.” They are incapable of it. Some of them just kill. They believe, that’s it—they kill anybody who doesn’t aspire to your level of malevolent conviction.

I’d love to talk to you about, you know, over the course of your career—and I feel that “career” is not as capacious a word as I want—you’ve been able to bring your activism and your intellectualism and your sort of art all onto the same plane, all operating at once. I learned that—and please correct me if I’m wrong—is Fela Kuti your cousin?

Fela Aníkúlápó, my cousin? Yes.

I had not known that, and it struck me as so apt, because here was another person whose art and intellect and political sense were all inter-implicated, all together. I wonder if just your upbringing made you feel that as a responsibility. Was that a natural step for you to be sort of an activist, politically aware, a true citizen in the deep sense of that word, and also an artist at the same time?