Home — Essay Samples — History — Hiroshima — A Discussion of Whether The US Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Was Justified

A Discussion of Whether The Us Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Was Justified

- Categories: Hiroshima

About this sample

Words: 2450 |

13 min read

Published: Nov 6, 2018

Words: 2450 | Pages: 5 | 13 min read

Was the United States Justified in Using the Atomic Bomb?

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1393 words

4 pages / 1969 words

1 pages / 425 words

2 pages / 977 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Hiroshima

The decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II remains one of the most controversial and morally complex actions in history. This essay delves into the arguments both for and against this [...]

The Second World War was a medium for numerous atrocities, with the Japanese Army infamous for their own wartime actions. In the present, we hear stories of unspeakable inhuman acts committed by the Imperial Army, yet what is [...]

Fukuzawa renders to us the notion of independence and self-respect by not only exemplifying the two qualities within his own actions but also by extensively insisting that his students follow in almost perfect alignment. As a [...]

Genghis Khan is one of the greatest leaders and conquerors in the history of the world. He grew to power with determination and brilliance, no matter how outmatched he was. After he took power, he went on to take over much of [...]

Culture plays a large role in everyone’s day to day lives, even if it not easily recognized. Julia Wood defines culture in her book Communication in Our Lives as a coherent system of understandings, traditions, values, [...]

Genghis Khan, a poor Mongolian child grew to be the greatest military genius the world has ever seen. He was one of the most successful and strategic military leaders in history and had a strong influence on other more recent [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Environment

- Globalization

- Japanese Language

- Social Issues

Hiroshima: History, City, Event

The name Hiroshima has come to stand for the catastrophic tragedy of war in general and for the horrifying potential for nuclear annihilation that has loomed in human affairs since the day in August 1945 when an atomic weapon was first used over that southwestern Japanese city. And yet, as important in world history as Hiroshima as cataclysmic event was, Hiroshima as a place, as a city, has a rich history, too. It is one that certainly now includes the war-time bombing, but that should not be reduced to the horrifically important event of the bombing alone.

Expanding the story of the city of Hiroshima beyond a tale of the atomic bombing can provide a fascinating lens onto the broader themes of Japanese historical experience. Resituating Hiroshima into its longer early modern and modern history also helps reveal the ways that Japan can serve as a national case study of common experiences of modern change around the world. The history of Hiroshima extends far back into centuries prior to the bomb. The formative era of the city was a time when samurai represented the ruling class of Japan, a time when the clash of modern empires that eventually resulted in Hiroshima’s obliteration could not have been imagined. The city also occupied an important place in the modern rise of the Japanese nation as an imperial power in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And finally, the history of Hiroshima also continued forward from the mid-summer date of its destruction in 1945. It became a city rebuilt by its citizens, one that lives on today as a bustling, thoroughly contemporary, global city, albeit one whose self-professed identity is now inextricably tied to the atom bomb and a postwar mission to promote disarmament around the world.

In this essay, I hope to provide some insight into the topic of Hiroshima in history as I have been exploring it in a course that I have taught a number of times. The class certainly explores the history of the atomic bombing of the city. But my goal also has been to expand the story of Hiroshima beyond that of the bomb alone and to use its history as a lens onto the history of cities, modern change, empire, and the newer field of what might be termed post-disaster studies. One of the challenges in this pedagogical endeavor, however, is the scarcity of historical writing about the city as such. The overwhelming preponderance of scholarship on Hiroshima, especially in the English language, is devoted to the bomb--the decision to drop it, the dramatic final days of the war in the U.S. and Japan leading up to the event, and the experience of those on the ground during the attack and the days after.

Among historians of urban history, Tokyo, in its earlier incarnation as the shogun’s city of Edo and in its later transformations as the capital of the modern nation, has enjoyed the lion’s share of attention both in Japan and the English-speaking world. Historical writing related to other important urban areas, such cities with national significance as Hiroshima, is not plentiful 1 .

The very first task I assign in my course is indeed designed to hint at the multiple stories of Hiroshima city that await to be discovered in the historical record but that have rarely been written about at any length in English. It serves certainly to show how the atomic bombing became the story of the city in later accounts. But the assignment also provides hints about the multiple perspectives of that event that have competed with one another over time. The assignment asks students to investigate encyclopedias published at various points during the modern period and to compare the entries in which Hiroshima city appears. Students have found that assignment yields interesting insights about the mostly cultural and economic portraits of the city written before the war, the later mid-century importance attached to the atomic bombing, and the way that those from different political perspectives viewed the history of the city as refracted through that wartime event. (If library—or on-line—resources allow, be sure that students study encyclopedias from different national perspectives. Those of the U.S., the Soviet Union, and Japan, in particular, suggest varying interpretations of the bombing. Another hint, too, is to encourage students to think creatively about the entries under which they search for the city. Not all references to Hiroshima will appear under the “Hiroshima” entry heading.)

What follows are introductions to seven facets of Hiroshima up to the time of the bombing that are helpful in placing the city, and the bomb itself, into larger historical contexts. I hope they suggest the outlines of the broader history of the city and its importance in national developments, while remaining mindful of the significance of the event of the bombing itself. In a following essay, I will also speak about life of the city after its obliteration in 1945. 1. Hiroshima as Warring-States Castle Town Beginning in the earliest years of the Japanese imperial state, the territory that makes up today’s Hiroshima prefecture was divided between two provinces, Bingo and Aki. The area was well situated and grew as a link between the western-most areas of the main Japanese island of Honshû, the Inland Sea, the island of Shikoku, and the imperial heartland of the rising Japanese state to the east. Long before Hiroshima was founded as a city, the Aki region was known for its religious significance. Possibly dating from as early as the late 6th c., though not cited in contemporary historical records until 811, the famous Itsukushima Shrine (Shinto) was located in Aki province on a small island (sometimes known as Miyajima, Shrine Island), a short distance west of where the later Hiroshima city would stand. Built in reverence for the island of Itsukushima and its Mount Misen, the shrine complex grew during the Heian period with the support of the powerful aristocratic clan, the Taira of the imperial capital. Over time this shrine to the sacred island became an important pilgrimage site. Today, Itsukushima Shrine has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. With its famous torii Shinto gate that appears to float in the water, it remains a major tourist and pilgrimage site just a short journey by train or ferry from Hiroshima 2 .

The city of Hiroshima itself was founded as a castle town on Hiroshima Bay in the late sixteenth century, a period when most of Japan’s medium and large-sized cities were founded, nearly all of them as castle towns constructed throughout Japan by competing warlords. The early history of the city is thus closely linked to the broader--and relatively long--history of urbanization in Japan. Urbanization began in this period of civil warfare and later witnessed, under different circumstances, successive waves of expansion in later centuries, particularly in the decades after the Meiji Restoration, then in the 1910s and 1920s, and then again after the Second World War.

The founder of Hiroshima was the powerful warlord Môri Terumoto, who was closely aligned by the late 1580s with Toyotomi Hideyoshi , the lord who was rapidly bringing the warring clans of sixteenth century Japan under his dominion. The home base of the Môri clan had long been western inland areas of the island of Honshu, where they had originally been assigned by the Kamakura Shogunate centuries before. By the end of the 1580s, Terumoto was flush from the successes of his alliance with Hideyoshi and Hideyoshi’s achievement of a sort of unifying overlordship among all warrior clans. In 1589, inspired no doubt by the construction by Hideyoshi himself of a massive new castle in Osaka, Terumoto set about building a grand castle headquarters for his clan on the shores of Hiroshima Bay, a location blessed by strategic and commercial advantages. This building project followed a pattern being repeated all over the country, as warlords, either in open battle with one another, or newly victorious, built immense fortifications and lavish headquarters. Terumoto moved in to his new castle, even before completion, in 1593.

Hiroshima castle was surrounded on three sides by mountains and situated on the delta of the river Ôta where it emptied into the bay. The branches of the river formed a series of islands before merging with the Inland Sea. One theory about the derivation of the name of Hiroshima castle is that the fortification was constructed on the largest of these low, flat islands of the time (“hiro” meaning wide and “shima” meaning island). From this location, the Môri clan controlled a large part of the commerce in the western portion of the Seto Inland Sea.

Paralleling the history of many other urban settlements in Japan during the last quarter of the sixteenth and the first quarter of the seventeenth centuries, Hiroshima soon became more than a mere castle fortification. As Terumoto’s samurai retainers gathered there, it grew into a bustling castle town. These samurai were soon joined in the new city by artisans, merchants, and workers of all stripes who made their lives around the castle. The Môri clan oversaw the building of bridges linking the islands of the Ôta river delta. The successors to the Môri in Hiroshima eventually also rerouted the Sanyô highway, which connected the expanding city to points east and west, so that the road went directly through the center of the burgeoning commercial center. The city would become by far the largest in the Chûgoku region of the main island of Japan and probably the sixth or seventh largest overall in Japan during the next three centuries. 2. Hiroshima as an Early-Modern City After Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s death and the competition to replace him as the lord of lords in Japan ensued, Môri Terumoto became the leader of the federation of warlords who attempted to stave off the rising power of the upstart Tokugawa Ieyasu far to the east. The Tokugawa forces defeated the forces allied against him, however, at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. As a result, the Tokugawa removed the Môri clan from their choice location in Hiroshima, dramatically reduced the size of their land holdings, and relocated them to the Chôshû domain in the very western tip of Honshû. In this way, the history of Hiroshima even has a link of sorts to the Meiji Restoration, the modern rebellion that 268 years later would overthrow the Tokugawa and launch Japanese society toward the construction of the modern nation-state: It was vassals of the Môri clan in the Chôshû domain who led the alliance of rebels that in the early days of 1868 orchestrated the final removal of the house of Tokugawa as shogun.

Tokugawa Ieyasu assigned the newly vacated, powerful Hiroshima domain and its capital city to Fukushima Masanori, who had allied himself with Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Sekigahara. By 1619, however, the Tokugawa shogun removed the Fukushima clan itself from Hiroshima for failing to receive permission from the shogun to rebuild portions of the Hiroshima castle damaged in a flood. The dismissal of the Fukushima clan from Hiroshima reflected the new, intricate system of political and military checks placed on the hundreds of lords enfiefed throughout Japan by the Tokugawa house. Each lord was allowed to maintain precisely one castle in his domain, and the shogun strictly surveilled any activity relating to the castle city fortifications of the lords or to their relations with neighboring domainal clan heads. Domainal lords ruled their fiefs at the pleasure of the shogun. Their relocation or demotion to non- daimyo (domainal lord) status could be the penalties for infractions within the quid pro quo alliance system of the Tokugawa regime .

In that same 1619, the Tokugawa shogun then assigned the Hiroshima fief to another ally, Asano Nagaakira, who was expected to serve there as a linchpin in the shogun’s network of control over the entire Chûgoku region of far southwestern Honshû. Hiroshima was thus ruled as the capital city of the Asano clan’s domain, in close alliance to the Tokugawa, until the end of the Tokugawa period.

These early years of the Tokugawa era continued to be a time of great city building. Nagaakira and his successors expanded on the earlier programs of the Môri and Fukushima lords to increase the infrastructure of the city. The Asano lords also promoted the continued expansion of the city through land reclamation projects in the bay. Much like its other important castle town counterparts during the relatively peaceful centuries of the Tokugawa period, Hiroshima became an early modern city, a place where samurai and commoner cultures intermingled and flourished, a center of intellectual production, the relatively cosmopolitan home of an expanding reading public, and a commercial hub during an era when Japan was to undergo a dramatic explosion in the scale of realm-wide commerce and a proto-industrial revolution in modes of economic production. 3. Hiroshima as Post-Meiji Restoration Modern City In the tumultuous and politically experimental first years following the Meiji revolution that overthrew the Tokugawa house, the new government set about to reconsider the administrative and political boundaries that had defined the old bakuhan (shogunal government and domainal governments) system of territorial rule in Japan. In 1871, the Meiji government dramatically announced the abolition of the domains and, by extension, their daimyo rulers. The new national government in Tokyo remade Hiroshima domain and the neighboring domain of Fukuyama into Hiroshima prefecture ( ken ), a new category of administrative unit over which the top executive official would be an appointed governor.

These changes were sudden and affected more than the domainal lords or those of the samurai caste alone. Commoners, too, felt great anxiety and suspicion over the rapid political and administrative changes. These uncertainties led to frequent uprising around Japan during the uncertain years after the Meiji revolution, including the incident when commoners led by a farmer named Buichirô launched a large armed uprising against local officials throughout the new prefecture of Hiroshima. The riot eventually was suppressed, and as so often happened in these cases, officials executed Buichirô and eight other leaders. In the eyes of those in charge at the prefectural and national levels, the progress represented in their eyes by the new political systems being erected could not be impeded. 3

A more thorough-going and formalized system of local rule, at the village, town, city, and prefectural levels, emerged during the 1880s and continued largely unchanged to 1945. In 1889, under this modern system of local and municipal governance, the national government in Tokyo officially designated Hiroshima as an incorporated city. It had roughly 83,000 residents. One of 31 cities recognized under the new system, Hiroshima took its place within the hierarchical administrative structures of the centralized nation-state system with which Japanese were rapidly replacing the institutions of centuries past. 4. Hiroshima as Industrial City Hiroshima city was also becoming modern in ways other than those related to its official municipal designation. As Japanese pursued new forms of economic and military strength during the Meiji period, Hiroshima grew in importance as a city of heavy industrial manufacturing. While not in those areas of the country most commonly identified with the industrial urban powerhouses--the Kantô area centered on Tokyo and the Nagoya-Kobe-Osaka nexus of cities--Hiroshima nevertheless also became an important city in the rise of Japanese industrial capitalism.

Recalling some of the economic reasons behind the original founding of the city, Hiroshima’s location on an important harbor and at the crossroads between the industrial centers of Kyûshû (especially the increasingly important city of Fukuoka), the Inland Sea and industrial cities further east contributed to its continuing success in the emerging new economy. The city became a critical modern transportation hub with the construction of the port of Ujina at the end of the 1880s. By the mid-1890s, the Sanyô Railroad was extended to Hiroshima, providing a link to Kobe and Shimonoseki in the east, and a new branch line from Ujina port connected the port to the main Sanyô Railroad station in the heart of the city. Entrepreneurs also constructed the sorts of light-industrial plants in Hiroshima that formed the basis of much of Japanese early industrialization during the modern period, including especially cotton mills. Located near the coal producing regions of northern Kyûshû and able to receive shipments of coal from overseas suppliers, the iron and steel industries also flourished in Hiroshima. In the city was also founded Tôyô Industries in 1920, later renamed the Mazda Corporation and famous in the post-WWII period as a global manufacturer of automobiles. By the wartime 1940s, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries constructed a major naval ship-building factory on the port waterfront of the city.

As measured by its ranking in terms of total population size, Hiroshima displayed a remarkable resilience in the face of the transformations from the end of the Tokugawa period through the modern economic changes of the first half of the twentieth century. At the end of the Tokugawa period, Hiroshima was the sixth most populous city in Japan. In 1935, its position was virtually unchanged at number seven. The top four cities in size also remained virtually unchanged in rank during that nearly 70-year period. Yet other cities did not fare so well in the transition to a modern economy, including most obviously the fifth largest city at the time of the Meiji transformation, Kanazawa. By 1935 its rank had fallen to number 22! Other major Tokugawa-era cities suffered similar fates, those such as Tôyama, Fukui, and Tottori, the latter of which dropped in size ranking from number 15 to 100 4 .

In the era of Japanese urban history before the rise of modern technologies, Hiroshima had flourished due to its location at the cross-roads of regional commerce, a location that had been decided based not only on economic advantage, but also pure military-strategic calculations. Many other major Tokugawa-era cities, however, had become large simply because the domains in which they were located were large and their lords were economically well off, though often not well aligned with the shogun. This weak position in relation to the shogun meant that such lords were placed in peripheral areas of the realm such as along the Sea of Japan coast, in the far north, or on the far side of the island of Shikoku. Such locations meant that during the modern period the cities associated with these old domainal lords found themselves located in peripheral regions of the emerging industrial economy. They often, therefore, shrank dramatically in size. Moreover, other cities that had been of smaller size under the Tokugawa system (e.g. Nagasaki) or that had not yet even existed as separate cities as such (e.g. Kobe) grew dramatically during the modern period based on their situational advantages given the growth industries of the modern economy.

Hiroshima’s advantages as a geographical crossroads, by contrast, remained undiminished across the early-modern and modern transition. Furthermore, Hiroshima was in the modern era also fortunately situated for taking advantage of the new fossil-fuel driven industrial technologies and shipping opportunities of the age. The result was Hiroshima’s extraordinarily long history as one of the premier cities in both the Tokugawa and modern eras. 5. Hiroshima as Imperial City

"The almost exclusive attention given to the day of the bombing itself ironically works to efface the key roles that the city did indeed play in modern empire and war-making."

Hiroshima’s modernity was also determined by the central role it played in the history of Japanese imperialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and in the important place that the modern Japanese military would play in the life of the city. The almost exclusive attention given to the day of the bombing itself ironically works to efface the key roles that the city did indeed play in modern empire and war-making. These modern historical roles do not necessarily by themselves make any case as to the morality or necessity of the dropping of the bomb. They do however place Hiroshima at the center of a longer history of national expansionism that by the end of 1945 did, rightly or wrongly, place Japan in the cross hairs of an atomic attack. Understanding the history of Japanese national strategies and expansion overseas as reflected in part in the history of Hiroshima helps to contextualize the bombing.

Hiroshima was a city where hundreds of thousands of civilians made their lives. Shops, small businesses, factories, banks, schools, hospitals, and government offices lined its streets. It was, however, also a military city. So common was the image of military personnel in the daily life of the city that it was dubbed by residents a “soldier’s city.” Military personnel could regularly be seen at the Chûgoku Regional Army and Fifth Army Division headquarters complex at Hiroshima castle, at their barracks and on drill grounds, and marching to and from transport ships and train stations as they entered the city or shipped out during the successive wars of the modern period by which Japanese extended their imperial reach.

Hiroshima first became a garrison city of the emerging modern military in 1871, and by 1886 the Fifth Division (of six total) of the military was headquartered at the old castle in the heart of the city. In addition, just two years later, the Japanese Imperial Naval Academy was relocated from Tokyo to the large island of Etajima in Hiroshima Bay. Etajima remained the officer training facility for the navy until the end of the war. It continues today as the Officer Candidate School of the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force and is also the location of the Museum of Naval History.

Beginning with the First Sino-Japanese war of 1894-95, Hiroshima became an assembly area for troops from all over the rest of Japan shipping out from the new Ujina port to the war zones of the Meiji period. In the first war with China, and then the war with Russia ten years later, the territory given over to military facilities in the city increased dramatically. By the end of those victorious wars, Hiroshima had also become a key military supply and ordinance depot, a training area, and communications center. As much as 10% of the city was dedicated to military purposes 5 . In addition, the war with China was the impetus behind the construction on the harbor island of Ninojima of a quarantine and disinfection station for all troops returning to Japan from war theaters and, soon enough, other parts of the empire. Because some of the very few medical facilities of any kind still standing after the atomic attack were on Ninojima, rescue troops ferried as many as 10,000 injured victims from the heart of the city to the island that day and over the following weeks. Many thousands died on the island, and their remains were buried there.

For a remarkable moment, Hiroshima’s place in the history of imperial wars even included the transformation of the city into the virtual imperial capital of the nation. During the First Sino-Japanese War, leaders moved the Meiji Emperor’s imperial command headquarters from Tokyo to Hiroshima to be at the center of the military logistics of this most important city in the war effort. During much of the war, the emperor thus resided in Hiroshima. Even the national parliament pulled up stakes and moved to Hiroshima, convening for a time during the war in a building hastily constructed for the purpose.

When Japan initiated full-scale war with China in 1937, the Fifth Army Division in Hiroshima once again was one of the first to the front. Over the successive years of the China war and then the war in the Pacific, the military appropriated increasing amounts of city land for facilities and military functions. As American forces seemed poised to launch an invasion of the Japanese home islands, the headquarters for the Second General Army, which had the job of defending the entire western part of Japan, was moved in April 1945 from Okinawa to Hiroshima northeast of the central military complex at the castle.

The military nature of the city was not always celebrated by its civilian citizens, however. In the early 1930s those in business complained to city and military authorities that too many city resources were being monopolized by the military. Particularly at issue was the desire of those in trade and manufacturing to have more facilities available for non-military shipping from Ujina port. In 1933 work began on facilities in the harbor to promote trade. Again in 1940, construction began on a new Hiroshima Industrial Port to promote the economic interests of the city. Reflecting the dominance of military concerns by the 1940s, however, part of the reclaimed land for the project ended up being used for an army airfield instead 6 . 6. Hiroshima as Targeted City In May 1945, American strategists placed Hiroshima on the short list of Japanese cities targeted for atomic attack. It was at that moment that the history of Hiroshima as a city intersected with the history of the event that would signal the dawn of the nuclear age. At the time that the United States dropped the bomb, Hiroshima was the 7th largest city in Japan (roughly comparable in relative ranking in today’s United States to the instantaneous obliteration of nearly all of San Diego). While estimates vary, the number of people believed to be in the city on the morning of the attack was about 370,000, including permanent civilian residents, commuters who came into the city that morning from surrounding suburbs for their jobs, military personnel stationed in Hiroshima, and Korean forced laborers. An estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people were vaporized, carbonized or otherwise killed in the initial heat (the fire-ball reached 300,000 degrees centigrade 1/10,000 of a second after the explosion), blast, and fires. At least that many again died by November of 1945 due to injuries and radiation.

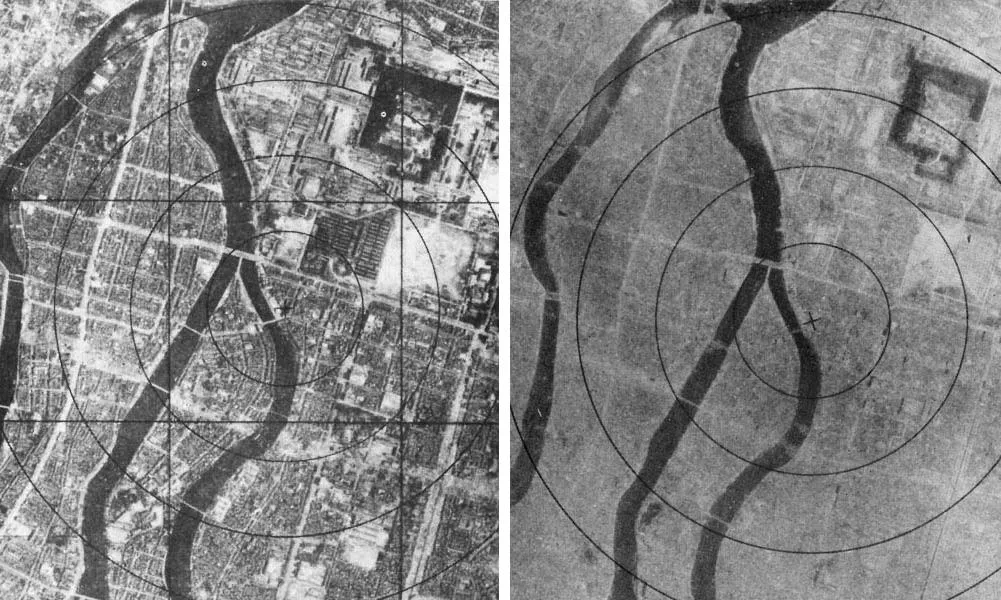

Hiroshima was one of just two very large cities in August 1945 that had not yet been the target of massive B-29 Superfortress air-raids (the other was Kyoto). This was not by logistical accident. American commanders purposely left the city untouched by fire-bomb attacks with the expressed idea that it might serve as a virgin testing ground for measuring the effects of an atomic weapon on a modern city. The city was among the few (including Kokura and Nagasaki) selected as final target choices (from among a much longer list) due to a variety of factors, including the shape of the landscape in which it sat. The bowl created by the hills surrounding the city on all but the harbor side would, planners believed, be especially conducive to achieving maximum destructive effect. Moreover, Hiroshima was a city in which many military troops were stationed and in which the Mitsubishi shipyard was located. In addition, American planners noted its importance as a transportation link.

The making of the atom bomb and the decision to drop it on Japan are the most familiar, though highly controversial aspects of the story of Hiroshima. Debate has raged about the decision to bomb since soon after the war ended. It is not possible here to canvass the massive literature related to the decision to use the bomb. Whether the Hiroshima bombing was morally justified, necessary, fundamentally different from the use of other highly destructive methods for attacking cities, ended the war, saved American lives, averted further deaths at the hands of Japanese aggressors, or unnecessarily initiated a costly and dangerous nuclear arms race with the Soviets are all huge subjects requiring their own separate treatments. The Japan Society has a resource page that can direct interested readers to works related to these questions and help them navigate this thorny terrain. My comments here are intended merely to point outward towards this ever-growing bomb scholarship and to give a sense of the contested nature of memory with respect to the atomic attack.

The orthodox perspective in the United States holds that the bomb brought the war to an early end and saved lives--American lives that would have been lost in any invasion of the main islands of Japan and perhaps Japanese lives, too, that would have been sacrificed in defense of the nation. This view was enunciated by American decision-makers at the time and held strong sway among most in the U.S. after the war. Yet relief that the war had ended was also accompanied by fears even in the U.S. of what the atomic age would bring. Many Americans assumed it was only a matter of time before they themselves would fall victim to bombing by others while others called for idealistic political responses, even a one-world government, as the only means to avoid mutual annihilation.

Soon enough after the war, some in the U.S., like the Federal Council of Churches, declared that the dropping of the bomb on innocent civilians was morally wrong. A more surprising evaluation was made in the summer of 1946 by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, which had been charged by FDR with assessing wartime air attacks. The Survey concluded that Japanese leaders would certainly have surrendered prior to the end of December 1945 even had the bomb not been used 8 . By the early 1960s, such scholars in the U.S. as Herbert Feis, began to support the argument that the bomb was not necessary. So-called revisionist scholars expanded on these views and over the following decades became more critical. They argued that the desire to cow the Soviets, racism, and the goal of punishing Japanese for Pearl Harbor and atrocities against POWs were all at work in the decision to use the new weapon. They also maintained that the supposed numbers of American lives saved were exaggerated after the fact by defenders of Truman’s decision. Some also offered a synthesis of these positions, suggesting that intimidating the Soviets was not a necessary consideration in the final decision, but that the possibility of also achieving this effect tended to foreclose any possibility of reconsideration of the decision to use the bomb 9 .

By the end of the twentieth century, contention over the way the bombing was remembered flared again to the surface. This was most famously true with the National Air and Space Musuem’s planned 50th anniversary exhibition of the Enola Gay, the airship used to drop the “Little Boy” atom bomb. Curators had designed the exhibit to display parts of the Enola Gay, but also to examine the reasons the bomb was used and review the debate that had taken place about the issue up to that time in 1995. These plans were met, however, by a barrage of criticism from veterans’ groups, politicians and others who attacked the planned exhibit as being “politically correct,” unjustifiably critical of American actions, and even unpatriotic. Under withering pressure from Congress and others, the Smithsonian scuttled nearly the entire exhibit. In the end, the forward fuselage of the Enola Gay was displayed, accompanied only by video interviews of the crew that had flown the mission to drop the bomb and text that discussed the development of the B-29 bombers used in air attacks on Japan 10 . Separate from questions related to the ultimate justification for the bomb, many among the scholarly community believed that the complete retreat of the museum marked a sad day for intellectual openness in the United States and the ways we view the complexities of history.

In the wake of the controversies over the Enola Gay exhibit, debate in the post-1995 years has been characterized by a resurgence of writing that justifies the bombing given the history of the war up to the summer of 1945 and the intractability of Japanese leaders. Defenders of the bombing have published works in recent years that maintain that revisionist critiques have held sway for too long. They claim that revisionists have made inaccurate and politically slanted use of the historical evidence and denounce those who criticize the bombing without consideration of Japanese actions in Asia leading up to that decision, actions that led to the death of millions of Asian soldiers and civilians. Such defenders as Robert P. Newman argue that the bombing did not represent the simple victimization of Japanese, but was justified given the number of lives potentially saved in the rest of East and Southeast Asia in light of the estimated rate of killing in the last days of the war being done by Japanese soldiers 11 . It should be noted, however, that, while it may not matter in terms of the ex post facto moral calculus being carried out in many of these arguments, saving specifically Asian lives does not ever seem to have figured as one of the expressed motives behind the decision of the Americans to launch the atomic strike.

For their part, Japanese forms of memorializing have themselves been criticized in the past as portraying Japanese as merely victims. Japanese public memories of the event, many pointed out, were presented without historical context, conveniently failing to address the aggression that Japanese had carried out throughout Asia beginning at least since 1931 and the many documented atrocities carried out by members of the Japanese military. Such was certainly true, for example, of the exhibits in the original main building of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The exhibits documented the devastating effects of the bomb on the city and its people, but provided no treatment of the war that led up to the event. The Peace Museum now, however, includes a newer east wing (opened 1994), which includes material on the long history of Japanese empire, the deaths of Koreans in Hiroshima under a slave labor regime, and Hiroshima’s own history as a military city. Such exhibits go some distance toward remedying the limited historical perspectives of the original approach. They are a testament to the fact that there has been at least some widening of perspectives in social memory of the war in Japan in the previous two decades or so. 7. Hiroshima as a Destroyed City Justified, tragic mistake, or war crime, the atomic attack reshaped the history of Hiroshima as an urban place as indelibly as any man-made or natural disaster ever could. A targeted city, Hiroshima became on that August morning also a thoroughly destroyed city. Accounts of the bomb never fail to mention that it packed the power of 15,000 tons of TNT. Yet this figure by itself means little to most of us. The conversion of the destructive force of the atom bomb to an equivalency in conventional explosives seems somehow, as large as the number is, to shrink the awfulness of the thing to something almost “normal.”

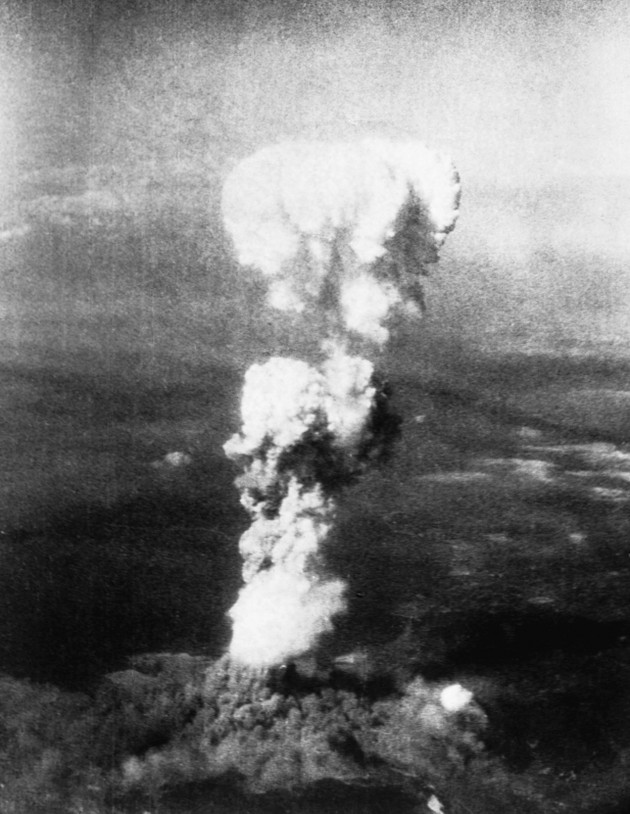

It is not until we see the photographs of the city taken the day of the event and soon after that the scale and completeness of the destruction begin dimly to be understood. And photographed the destroyed city was. There were photos of the still climbing mushroom cloud, as seen from nearly directly below and from immensely far away. There were photos of the effects of the impossibly powerful blast--photos of demolished massive granite buildings and of flying shrapnel wedged perfectly under heavy stone objects, lodged there in the moment that the stones had been momentarily tilted up by the blast. There were photos of dazed survivors gathering in small dusty, half-clothed groups. In the days and weeks that followed, there were also panoramic photos of kilometer after kilometer of the once crowded city now quite utterly flattened and blackened. From the hypocenter in nearly all directions stood nothing to impede one’s view from one side of the city to the other. Staring at these photos today, the horrible power of the bomb is frightening, even more so when it is remembered how small that 1945 weapon was by comparison to those in nuclear stockpiles today.

These photographs became just one category of evidence among many gathered after the attack in a massive attempt to catalogue, measure, and analyze just what had been done to the city at what moment of the bomb’s explosion and by which of the three means of destruction that the bomb meted out (heat rays, blast, and radiation). Scientists and medical teams from the United States, aided in the Occupation months that followed by Japanese counterparts, pieced together the details of the explosion and its effects. In essence, Hiroshima was transformed at the moment of its destruction into a city-sized laboratory for discovering the outcomes on structures and people of an atomic attack. The technical dispassion of the American documents ordering the “recording of all of the available data” about the destroyed city betrays the wartime context that underlay the research projects, but also a queasy realization by those at the time that Hiroshima might now represent the new face of warfare. Such research was “of vital importance to our country” declared one such U.S. document, which chillingly went on to explain that such a “unique opportunity may not again be offered until the next world war.” 12

Even the survivors, along with their offspring, became scientific specimens as scientists in the U.S. and Japan examined them for decades following the attack to record the exotic disorders that resulted from their exposure to the bombing. For example, medical teams studied the thick “keloid” scarring of heat flash burns. Little was also known about the dangerous effects of radiation exposure, and as surprising as it may seem today, most scientists and medical professionals believed before entering the city that there was “little indication” that much disease and death would be caused by the radiation of the bomb. 13 Facts to the contrary were quickly evident, however, as thousands died appalling radiation deaths in the months that followed. Research on the long-term, multi-generational consequences of radiation poisoning is still being studied today among survivors and their progeny.

The destroyed city also soon enough became a mapped city. Researchers eventually translated their findings on the destruction of the city into detailed maps that displayed the geographic distribution of damage. The effects of the blast were further disaggregated on these maps into various categories, color-coded to indicate partial and complete destruction and building loss by blast and later fire. Other maps recorded the geography of radiation. Bulbous swathes of color spreading northwest from the point of explosion at the middle of the city indicated the deadly reach of fall-out plumes and the territory as far as fifteen miles distant from the hypocenter over which black, radioactive rain had fallen as a consequence of the mushroom cloud. With their concentric rings marking the distance in kilometers from the hypocenter of the blast, all of these maps were bleak foreshadows of the similarly scientific maps of New York City, Washington, D.C. or Moscow that would soon enough registered the potential for even greater thermonuclear destruction so familiar during the nuclear arms race of the Cold War.

The extent of destruction that these maps displayed was almost unimaginable. 63% of all buildings within the city were totally destroyed and another 29% severely damaged beyond all repair. At a distance of two kilometers in all directions all wooden buildings were destroyed and burned. Anyone within 500 meters of the explosion would have had no time to feel the thermal flash or hear the blast. The entire area was nearly instantaneously destroyed and burned to ashes. The survivor believed to have been closest to ground zero was a mere 100 meters away, but he was in a basement room at the time and one of the very few to survive anywhere near that close to the point of explosion. Researchers estimate that between 80 to 100% of those who were exposed near the location of the blast died on the day of bombing. Even as far as 1.2 kilometers away, 50% perished that day. All survivors of the initial blast who were within a kilometer of the explosion received a dose of radiation that would be expected to kill half of those exposed to it within a month.

Hiroshima destroyed also became a city of relics and reminders. Much like Americans’ current desire to remember the September 11th attacks by displaying large chunks of the broken steel of the World Trade Center, citizens of Hiroshima, on a larger scale, dismantled and saved parts of the broken city--twisted iron and steel; the chemically altered surfaces of marble blocks; radioactive “black rain”-streaked walls; the shadows on stone of persons instantly incinerated. They did so to record what had occurred, to warn against the violence of the past, and simply to remember. Many of these monuments to the experience of the bombed city can be seen on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum ( official site ).

The destroyed city was obviously a space of great death and suffering, but also of survival. A number of accounts by survivors have become well-known around the world, translated into many languages and a variety of media. Barefoot Gen , a “comic” (what today would be called a graphic novel) written and drawn by Nakazawa Keiji beginning in 1973, is based on Nakazawa’s own boyhood experience as a bomb victim, but also includes a critical portrayal of the jingoistic militarism of wartime Japanese society. Later repackaged in multi-volume book form, Barefoot Gen has sold millions of copies around the world and been adapted several times for film and television.

Several writers already of some renown at the time of the bombing attempted immediately to put their experiences of survival into first-person forms. One was Ôta Yôkô, whose City of Corpses features a documentary style of description of her experiences and reactions to the bombing, but is also often didactic in tone. Hara Tamiki was another such professional writer. He produced an autobiographical short story, “Summer Flowers,” that is an elegiac yet also hauntingly simple account, in slightly fictionalized form, of his experiences in the destroyed city. As in the laconic mode with which the narrator describes his being in the toilet at the moment of the bombing, Hara’s restrained story records the frequent happenstances determining life and death during the attack. Although he first jotted the notes for “Summer Flowers” in the immediate midst of great death, Hara was accompanied by others like himself whom pure accident had put relatively out of harm’s way on the day of the bomb and who managed to survive in the improbable circumstances of the burned out city. In an essay to follow, I will consider the survival of Hiroshima after its destruction. The essay will discuss the city in four of its interconnected postwar guises: reconstructed city, peace city, memorial city, and global city.

Receive Website Updates

Please complete the following to receive notification when new materials are added to the website.

Was It Right?

Most of the debate over the atomic bombing of Japan focuses on the unanswerable question of whether it was necessary. But that skirts the question of its morality.

I imagine that the persistence of that question irritated Harry Truman above all other things. The atomic bombs that destroyed the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki fifty years ago were followed in a matter of days by the complete surrender of the Japanese empire and military forces, with only the barest fig leaf of a condition—an American promise not to molest the Emperor. What more could one ask from an act of war? But the two bombs each killed at least 50,000 people and perhaps as many as 100,000. Numerous attempts have been made to estimate the death toll, counting not only those who died on the first day and over the following week or two but also the thousands who died later of cancers thought to have been caused by radiation. The exact number of dead can never be known, because whole families—indeed, whole districts—were wiped out by the bombs; because the war had created a floating population of refugees throughout Japan; because certain categories of victims, such as conscript workers from Korea, were excluded from estimates by Japanese authorities; and because as time went by, it became harder to know which deaths had indeed been caused by the bombs. However many died, the victims were overwhelming civilians, primarily the old, the young, and women; and all the belligerents formally took the position that the killing of civilians violated both the laws of war and common precepts of humanity. Truman shared this reluctance to be thought a killer of civilians. Two weeks before Hiroshima he wrote of the bomb in his diary, “I have told [the Secretary of War] Mr. Stimson to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.” The first reports on August 6, 1945, accordingly described Hiroshima as a Japanese army base.

This fiction could not stand for long. The huge death toll of ordinary Japanese citizens, combined with the horror of so many deaths by fire, eventually cast a moral shadow over the triumph of ending the war with two bombs. The horror soon began to weigh on the conscience of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the secret research project at Los Alamos, New Mexico, that designed and built the first bombs. Oppenheimer not only had threatened his health with three years of unremitting overwork to build the bombs but also had soberly advised Henry Stimson that no conceivable demonstration of the bomb could have the shattering psychological impact of its actual use. Oppenheimer himself gave an Army officer heading for the Hiroshima raid last minute instructions for proper delivery of the bomb.

Don’t let them bomb through clouds or through an overcast. Got to see the target. No radar bombing; it must be dropped visually. ... Of course, they must not drop it in rain or fog. Don't let them detonate it too high. The figure fixed on is just right. Don't let it go up or the target won’t get as much damage.

These detailed instructions were the result of careful committee work by Oppenheimer and his colleagues. Mist or rain would absorb the heat of the bomb blast and thereby limit the conflagration, which experiments with city bombing in both Germany and Japan had shown to be the principal agent of casualties and destruction. Much thought had also been given to finding the right city. It should be in a valley, to contain the blast; it should be relatively undamaged by conventional air raids, so that there would be no doubt of the bomb's destructive power; an educated citizenry was desired, so that it would understand the enormity of what had happened. The military director of the bomb project, General Leslie Groves, thought the ancient Japanese imperial capital of Kyoto would be ideal, but Stimson had spent a second honeymoon in Kyoto, and was afraid that the Japanese would never forgive or forget its wanton destruction; he flatly refused to leave the city on the target list. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed instead. On the night of August 6 Oppenheimer was thrilled by the bomb's success. He told an auditorium filled with whistling, cheering, foot-stomping scientists and technicians that he was sorry only that the bomb had not been ready in time for use on Germany. The adrenaline of triumph drained away following the destruction of Nagasaki, on August 9. Oppenheimer, soon offered his resignation and by mid-October had severed his official ties. Some months later he told Truman in the White House, “Mr. President, I have blood on my hands.” Truman was disgusted by this cry-baby attitude. “I told him,” Truman said later, “the blood was on my hands—let me worry about that.” Till the end of his life Truman insisted that he had suffered no agonies of regret over his decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the pungency of his language suggests that he meant what he said. But it is also true that he ordered a halt to the atomic bombing on August 10, four days before the Japanese Emperor surrendered, and the reason, according to a Cabinet member present at the meeting, was that “he didn’t like the idea of killing ... ‘all those kids.’” Was it right? Harry Truman isn’t the only one to have disliked the question. Historians of the war, of the invention of the atomic bomb, and of its use on Japan have almost universally chosen to skirt the question of whether killing civilians can be morally justified. They ask instead, Was it necessary? Those who say it was necessary argue that a conventional invasion of Japan, scheduled to begin on the southernmost island of Kyushu on November 1, 1945, would have cost the lives of large numbers of Americans and Japanese alike. Much ink has been spilled over just how large these numbers would have been. Truman in later life sometimes said that he had used the atomic bomb to save the lives of half a million or even a million American boys who might have died in an island-by-island battle to the bitter end for the conquest of Japan. Where Truman got those numbers is hard to say. In the spring of 1945, when it was clear that the final stage of the war was at hand, Truman received a letter from former President Herbert Hoover urging him to negotiate an end to the war in order to save the “500,000 to 1 million American lives” that might be lost in an invasion. But the commander of the invasion force, General Douglas MacArthur, predicted nothing on that scale. In a paper prepared for a White House strategy meeting held on June 18, a month before the first atomic bomb was tested, MacArthur estimated that he would suffer about 95,000 casualties in the first ninety days—a third of them deaths. The conflict of estimates is best explained by the fact that they were being used at the time as weapons in a larger argument. Admirals William Leahy and Ernest J. King thought that Japan could be forced to surrender by a combination of bombing and naval blockade. Naturally they inflated the number of casualties that their strategy would avoid. MacArthur and other generals, convinced that the war would have to be won on the ground, may have deliberately guessed low to avoid frightening the President. It was not easy to gauge how the battle would go. From any conventional military perspective, by the summer of 1945 Japan had already lost the war. The Japanese navy mainly rested on the bottom of the ocean; supply lines to the millions of Japanese soldiers in China and other occupied territories had been severed; the Japanese air force was helpless to prevent the almost nightly raids by fleets of B-29 bombers, which had been systematically burning Japanese cities since March; and Japanese petroleum stocks were close to gone. The battleship Yamato , dispatched on a desperate mission to Okinawa in April of 1945, set off without fuel enough to return. But despite this hopeless situation the Japanese military was convinced that a “decisive battle” might inflict so many casualties on Americans coming ashore in Kyushu that Truman would back down and grant important concessions to end the fighting. Japan’s hopes were pinned on “special attack forces,” a euphemism for those engaged in suicide missions, such as kamikaze planes loaded with explosives plunging into American ships, as had been happening since 1944. During the spring and summer of 1945 about 8,000 aircraft, along with one-man submarines and “human torpedoes,” had been prepared for suicide missions, and the entire Japanese population had been exhorted to fight, with bamboo spears if necessary, as “One Hundred Million Bullets of Fire.” Military commanders were so strongly persuaded that honor and even victory might yet be achieved by the “homeland decisive battle” that the peace faction in the Japanese cabinet feared an order to surrender would be disobeyed. The real question is not whether an invasion would have been a ghastly human tragedy, to which the answer is surely yes, but whether Hoover, Leahy, King, and others were right when they said that bombing and blockade would end the war. Here the historians are on firm ground. American cryptanalysts had been reading high-level Japanese diplomatic ciphers and knew that the government in Tokyo was eagerly pressing the Russians for help in obtaining a negotiated peace. The sticking point was narrow: the Allies insisted on unconditional surrender; the Japanese peace faction wanted assurances that the imperial dynasty would remain. Truman knew this at the time. What Truman did not know, but what has been well established by historians since, is that the peace faction in the Japanese cabinet feared the utter physical destruction of the Japanese homeland, the forced removal of the imperial dynasty, and an end to the Japanese state. After the war it was also learned that Emperor Hirohito, a shy and unprepossessing man of forty-four whose first love was marine biology, felt pressed to intervene by his horror at the bombing of Japanese cities. The devastation of Tokyo left by a single night of firebomb raids on March 9–10, 1945, in which 100,000 civilians died, had been clearly visible from the palace grounds for months thereafter. It is further known that the intervention of the Emperor at a special meeting, or gozen kaigin , on the night of August 9–10 made it possible for the government to surrender. The Emperor’s presence at a gozen kaigin is intended to encourage participants to put aside all petty considerations, but at such a meeting, according to tradition, the Emperor does not speak or express any opinion whatever. When the cabinet could not agree on whether to surrender or fight on, the Premier, Kantaro Suzuki, broke all precedent and left the military men speechless when he addressed Hirohito, and said, “With the greatest reverence I must now ask the Emperor to express his wishes.” Of course, this had been arranged by the two men beforehand. Hirohito cited the suffering of his people and concluded, “The time has come when we must bear the unbearable.” After five days of further confusion, in which a military coup was barely averted, the Emperor broadcast a similar message to the nation at large in which he noted that “the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb. ... “ Are those historians right who say that the Emperor would have submitted if the atomic bomb had merely been demonstrated in Tokyo Bay, or had never been used at all? Questions employing the word “if” lack rigor, but it is very probable that the use of the atomic bomb only confirmed the Emperor in a decision he had already reached. What distressed him was the destruction of Japanese cities, and every night of good bombing weather brought the obliteration by fire of another city. Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and several other cities had been spared from B-29 raids and therefore offered good atomic-bomb targets. But Truman had no need to use the atomic bomb, and he did not have to invade. General Curtis LeMay had a firm timetable in mind for the 21st Bomber Command; he had told General H. H. (“Hap”) Arnold, the commander in chief of the Army Air Corps, that he expected to destroy all Japanese cities before the end of the fall. Truman need only wait. Steady bombing, the disappearance of one city after another in fire storms, the death of another 100,000 Japanese civilians every week or ten days, would sooner or later have forced the cabinet, the army, and the Emperor to bear the unbearable. Was it right? The bombing of cities in the Second World War was the result of several factors: the desire to strike enemies from afar and thereby avoid the awful trench-war slaughter of 1914–1918; the industrial capacity of the Allies to build great bomber fleets; the ability of German fighters and anti-aircraft to shoot down attacking aircraft that flew by daylight or at low altitudes; the inability of bombers to strike targets accurately from high altitudes; the difficulty of finding all but very large targets (that is, cities) at night; the desire of airmen to prove that air forces were an important military arm; the natural hardening of hearts in wartime; and the relative absence of people willing to ask publicly if bombing civilians was right. “Strategic bombing” got its name between the wars, when it was the subject of much discussion. Stanley Baldwin made a deep impression in the British House of Commons in 1932 when he warned ordinary citizens that bombing would be a conspicuous feature of the next war and that “the bomber will always get through.” This proved to be true, although getting through was not always easy. The Germans soon demonstrated that they could shoot down daytime low-altitude “precision” bombers faster than Britain could build new planes and train new crews. By the second year of the war the British Bomber Command had faced the facts and was flying at night, at high altitudes, to carry out “area bombing.” The second great discovery of the air war was that high-explosive bombs did not do as much damage as fire. Experiments in 1942 on medieval German cities on the Baltic showed that the right approach was high-explosive bombs first, to smash up houses for kindling and break windows for drafts, followed by incendiaries, to set the whole alight. If enough planes attacked a small enough area, they could create a fire storm—a conflagration so intense that it would begin to burn the oxygen in the air, creating hundred-mile-an-hour winds converging on the base of the fire. Hamburg was destroyed in the summer of 1943 in a single night of unspeakable horror that killed perhaps 45,000 Germans. While the British Bomber Command methodically burned Germany under the command of Sir Arthur Harris (called Bomber Harris in the press but Butch—short for “Butcher”—by his own men), the Americans quietly insisted that they would have no part of this slaughter but would instead attack “precision” targets with “pinpoint” bombing. But American confidence was soon eroded by daylight disasters, including the mid-1943 raid on ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt, in which sixty-three of 230 B-17s were destroyed for only paltry results on the ground. Some Americans continued to criticize British plans for colossal city-busting raids as "baby-killing schemes," but by the end of 1943, discouraged by runs of bad weather and anxious to keep planes in the air, the commander of the American Air Corps authorized bombing “by radar”—that is, attacks on cities, which radar could find through cloud cover. The ferocity of the air war eventually adopted by the United States against Germany was redoubled against Japan, which was even better suited for fire raids, because so much of the housing was of paper and wood, and worse suited for “precision” bombing, because of its awful weather and unpredictable winds at high altitudes. On the night of March 9–10, 1945, General LeMay made a bold experiment: he stripped his B-29s of armament to increase bomb load and flew at low altitudes. As already described, the experiment was a brilliant success. By the time of Hiroshima more than sixty of Japan’s largest cities had been burned, with a death toll in the hundreds of thousands. No nation could long resist destruction on such a scale—a conclusion formally reached by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in its Summary Report ( Pacific War ): “Japan would have surrendered [by late 1945] even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war [on August 8], and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” Was it right? There is an awkward, evasive cast to the internal official documents of the British and American air war of 1939–1945 that record the shift in targets from factories and power plants and the like toward people in cities. Nowhere was the belief ever baldly confessed that if we killed enough people, they would give up; but that is what was meant by the phrase “morale bombing,” and in the case of Japan it worked. The mayor of Nagasaki recently compared the crime of the destruction of his city to the genocide of the Holocaust, but whereas comparisons—and especially this one—are invidious, how could the killing of 100,000 civilians in a day for a political purpose ever be considered anything but a crime? Fifty years of argument over the crime against Hiroshima and Nagasaki has disguised the fact that the American war against Japan was ended by a larger crime in which the atomic bombings were only a late innovation—the killing of so many civilians that the Emperor and his cabinet eventually found the courage to give up. Americans are still painfully divided over the right words to describe the brutal campaign of terror that ended the war, but it is instructive that those who criticize the atomic bombings most severely have never gone on to condemn all the bombing. In effect, they give themselves permission to condemn one crime (Hiroshima) while enjoying the benefits of another (the conventional bombing that ended the war). Ending the war was not the only result of the bombing. The scale of the attacks and the suffering and destruction they caused also broke the warrior spirit of Japan, bringing to a close a century of uncontrolled militarism. The undisguisable horror of the bombing must also be given credit for the following fifty years in which no atomic bombs were used, and in which there was no major war between great powers. It is this combination of horror and good results that accounts for the American ambivalence about Hiroshima. It is part of the American national gospel that the end never justifies the means, and yet it is undeniable that the end—stopping the war with Japan—was the immediate result of brutal means. Was it right? When I started to write this article, I thought it would be easy enough to find a few suitable sentences for the final paragraph when the time came, but in fact it is not. What I think and what I feel are not quite in harmony. It was the horror of Hiroshima and fear of its repetition on a vastly greater scale which alarmed me when I first began to write about nuclear weapons (often in these pages), fifteen years ago. Now I find I have completed some kind of ghastly circle. Several things explain this. One of them is my inability to see any significant distinction between the destruction of Tokyo and the destruction of Hiroshima. If either is a crime, then surely both are. I was scornful once of Truman’s refusal to admit fully what he was doing; calling Hiroshima an army base seemed a cruel joke. Now I confess sympathy for the man—responsible for the Americans who would have to invade; conscious as well of the Japanese who would die in a battle for the home islands; wielding a weapon of vast power; knowing that Japan had already been brought to the brink of surrender. It was the weapon he had. He did what he thought was right, and the war ended, the killing stopped, Japan was transformed and redeemed, fifty years followed in which this kind of killing was never repeated. It is sadness, not scorn, that I feel now when I think of Truman's telling himself he was not “killing ‘all those kids.’” The bombing was cruel, but it ended a greater, longer cruelty. They say that the fiftieth anniversaries of great events are the last. Soon after that the people who took part in them are all dead, and the young have their own history to think about, and the old questions become academic. It will be a relief to move on.

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The legacy of john hersey’s “hiroshima”.

Seventy-five years ago, journalist John Hersey’s article “Hiroshima” forever changed how Americans viewed the atomic attack on Japan.

On August 31, 1946, the editors of The New Yorker announced that the most recent edition “will be devoted entirely to just one article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb.” Though President Harry S. Truman had ordered the use of two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki a year earlier, the staff at The New Yorker believed that “few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon, and that everyone might well take time to consider the terrible implications of its use.”

Theirs was a weighty introduction to wartime reporter John Hersey’s four-chapter account of the wreckage of the atomic bomb, but such a warning was necessary for the stories of human suffering The New Yorker ’s readers would be exposed to.

Hersey was certainly not the first journalist to report on the aftermath of the bombs. Stories and newsreels provided details of the attacks: the numbers wounded and dead, the staggering estimated costs—numerically and culturally—of property lost, and some of the visual horrors. But Hersey’s account focused on the human toll of the bombs and the individual stories of six survivors of the nuclear attack on Hiroshima rather than statistics.

View of Hiroshima after the bombing, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Hersey was both a respected reporter and a gifted novelist, two occupations that provided him with the skills and compassion necessary to write his extensive essay on Hiroshima. Born in Tientsin, China in 1914 to missionary parents, Hersey later returned to the states and graduated from Yale University in 1936. Shortly after, he began a career as a foreign correspondent for Time and Life magazines and covered current events in Asia, Italy, and the Soviet Union from 1937 to 1946. Hersey won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel A Bell For Adano (a story of the Allied occupation of a town in Sicily) in 1944, and his talents for fiction inspired his later nonfiction writing. He spent three weeks in May of 1946 on assignment for The New Yorker interviewing survivors of the atomic attacks and returned home where he began to write what would become “Hiroshima.”

Hersey was determined to present a real and raw image of the impact of the bomb to American readers. They could not depend on censored materials from the US Occupying Force in Japan to accurately present the wreckage of the atomic blast. Hersey’s graphic and gut-wrenching descriptions of the misery he encountered in Hiroshima offered what officials could not: the human cost of the bomb. He wanted the story of the victims he interviewed to speak for themselves, and to reconstruct in dramatic yet relatable detail their experiences.

Portrait of John Hersey by Carl Van Vechten from 1958, courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Hersey organized his article around six survivors he met in Hiroshima. These were “ordinary” Japanese with families, friends, and jobs just like Americans. Miss Toshiko Sasaki was a 20 year old former clerk whose leg had been severely damaged by fallen debris during the attack and she was forced to wait for days for medical treatment. Kiyoshi Tanimoto was a pastor of a Methodist Church who appeared to be suffering from “radiation sickness,” a plight that befell another of Hersey’s interviewees, German-born Jesuit Priest Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge. Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura’s husband died while serving with the Japanese army, and she struggled to rebuild her life with her young children after the attack. Finally, two doctors—Masakazu Fujii and Terufumi Sasaki—were barely harmed but witnessed the death and destruction around them as they tended to the victims.

Each of the essay’s four chapters delves into the experiences of the six individuals before, during, and after the bombing, but it’s Hersey’s unembellished language that makes his writing so haunting. Unvarnished descriptions of “pus oozing” from wounds and the stench of rotting flesh are found throughout all of the survivors’ stories. Mr. Tanimoto recounted his search for victims and encountering several naked men and women with “great burns…yellow at first, then red and swollen with skin sloughed off and finally in the evening suppurated and smelly.” Tanimoto—for all of the chaos that surrounded him—recalled that “the silence in the grove by the river, where hundreds of gruesomely wounded suffered together, was one of the most dreadful and awesome phenomena of his whole experience.”

“The hurt ones were quiet; no one wept, much less screamed in pain; no one complained; none of the many who died did so noisily; not even the children cried; very few people even spoke.”

John Hershey

At the same time, Hersey also describes the prevalence of radiation sickness amongst the victims. Many who had suffered no physical injuries, including Mrs. Nakamura, reported feeling nauseated long after the attack. Father Kleinsorge “complained that the bomb had upset his digestion and given him abdominal pains” and his white blood count was elevated to seven times the normal level while he consistently ran a 104 degree temperature. Doctors encountered many instances of what would become known as radiation poisoning but often assured their patients that they would “be out of the hospital in two weeks.” Meanwhile, they told families, “All these people will die—you’ll see. They go along for a couple of weeks and then they die.”

Hersey’s interviews also highlighted the inconceivable impact of the nuclear blast. Americans may have believed that such a powerful explosion would be deafening, but the interviewees offered a different take. More than a sound, most of the interviewees described blinding light at the moment of the attack. Dr. Terufumi Sasaki remembered the light of the bomb “reflected, like a gigantic photographic flash,” through an open window while Father Kleinsorge later realized that the “terrible flash” had “reminded him of something he had read as a boy about a large meteor colliding with the earth.” Hersey’s title of the first chapter is, in fact, “A Noiseless Flash.”

The attack also left a bizarre mark on the landscape. While buildings were reduced to rubble, the power of the bomb “had not only left the underground organs of plants intact; it had stimulated them.” Miss Sasaki was surprised upon her return to Hiroshima in September by the “blanket of fresh, vivid, lush, optimistic green” plants that grew over the destruction and the day lilies that blossomed from the heaps of debris. Others remembered eating pumpkins and potatoes that were perfectly roasted in the ground by the fantastic heat and energy of the bomb.

With its raw descriptions of the terror and destruction faced by the residents of Hiroshima, Hersey’s article broke records for The New Yorker and became the first human account of the attack for most Americans. All 300,000 editions of The New Yorker sold out almost immediately. The success of the article resulted in a reprinted book edition in November that continues to be read by many around the world. Meanwhile, Hersey remained relatively removed from his work, refusing most interviews on the book and choosing instead to let the work speak for itself.

Decades later, his six interviewees remain a human connection to the attacks and the deep, philosophical questions they raised. “A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors,” Hersey said, leaving them to “still wonder why they lived when so many others died,” or “too busy or too weary or too badly hurt to care that they were the objects of the first great experiment in the use of the atomic power which…no country except the United States, with its industrial know-how, its willingness to throw two billion gold dollars into an important wartime gamble, could possibly have developed.”

This article is part of a series commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II made possible by the Department of Defense.

Stephanie Hinnershitz, PhD

Stephanie Hinnershitz is a historian of twentieth century US history with a focus on the Home Front and civil-military relations during World War II.

From Hiroshima to Human Extinction: Norman Cousins and the Atomic Age

In 1945 the American intellectual, Norman Cousins, was one of the first to raise terrifying questions for humanity about the successful splitting of the atom.

The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the American B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World with Author Lesley Blume

This presentation of FALLOUT , which premiered on the Museum’s Facebook page, recounts how John Hersey got the story that no other journalist could—and how he subsequently played a role in ensuring that no nuclear attack has happened since, possibly saving millions of lives.

Should Atomic Bombs Never Be Used as a Weapon?

From the Manhattan Project to Hiroshima and atomic diplomacy.

Explore Further

Marine Killed on Guadalcanal Laid to Rest in New Orleans

The remains of Private Randolph Ray Edwards were identified and accounted for more than 80 years after his death.

Eleanor Roosevelt's My Day Column from Guadalcanal

In her September 16, 1943, My Day column, Eleanor Roosevelt reflects on her visit to Guadalcanal, where she witnessed the lasting impact of the sacrifices made by US soldiers.

Douglas C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 became the mainstay for airborne drops and were used in this role extensively for Operations Overlord, Dragoon, Market Garden, and Varsity.

The Battle of Peleliu: The Forgotten Hell

Underscoring its ferocity, future commandant of the Marine Corps General Clifton Cates argued that “the fight for Peleliu was one of the most vicious and stubbornly defended battles of the war.”

Liberation of Morotai: A Bloodless Peleliu

While Peleliu remains a fixture of Pacific war memory, Morotai is overlooked and virtually forgotten in histories of the Pacific theater.

Eleanor Roosevelt's Response to Germany's Invasion of Poland

In her September 2, 1939, My Day column, Eleanor Roosevelt reacts to the news of Germany's invasion of Poland, sharing her dismay at Adolf Hitler's actions and expressing sorrow for the European nations facing the crisis.

The Allies of World War II

World War II was a global conflict involving nearly every country in the world. But who was on each side—and why?

The Axis Powers of World War II

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 31, 2024 | Original: November 18, 2009