WordPress database error: [The MySQL server is running with the --read-only option so it cannot execute this statement] DELETE FROM `wp_options` WHERE `option_name` = '_site_transient_timeout_wp_theme_files_patterns-405a0fe11f6fd17c8d23c8388c257caa'

WordPress database error: [The MySQL server is running with the --read-only option so it cannot execute this statement] INSERT INTO `wp_options` (`option_name`, `option_value`, `autoload`) VALUES ('_site_transient_wp_theme_files_patterns-405a0fe11f6fd17c8d23c8388c257caa', 'a:2:{s:7:\"version\";s:5:\"1.0.0\";s:8:\"patterns\";a:0:{}}', 'off') ON DUPLICATE KEY UPDATE `option_name` = VALUES(`option_name`), `option_value` = VALUES(`option_value`), `autoload` = VALUES(`autoload`)

WordPress database error: [The MySQL server is running with the --read-only option so it cannot execute this statement] UPDATE `wp_options` SET `option_value` = '1731927478.6576099395751953125000' WHERE `option_name` = '_transient_doing_cron'

- Explore Art + Culture

Site Search

The collections and archives.

Looking for an object or work of art?

Looking for archival materials?

Buddhist Architecture in Korea *

In this essay

A buddhist temple is a complex of buildings, buildings and structural elements, relationship between image halls and pagodas, diversity in architectural forms.

- Return to Once Upon a Roof: Vanished Korean Architecture Exhibition

Kim Bongryol PhD, Professor of Architecture, Korea National University of Arts

Buddhism was introduced to China from India and Central Asia, and it was already prevalent in China by the fourth century when the religion was first introduced to the Korean peninsula. At that time, the peninsula was divided into three separate kingdoms: Goguryeo 高句麗 (37 BCE–668 CE), Baekje 百濟 (18 BCE–660 CE), and Silla 新羅 (57 BCE–935 CE). Buddhism was welcomed by the royal houses of the Three Kingdoms, which pursued Buddhism competitively. The royal houses took the principal initiative for its spread, and Buddhism flourished in uniquely Korean forms, which came to characterize the architecture of Buddhist temples.

Following the introduction of Buddhism, the royal houses of the Three Kingdoms constructed huge temples in the heart of their capital cities. Goguryeo built Jeongneungsa 定陵寺 in Pyeongyang 平壤 to manage the royal tombs. Baekje constructed Mireuksa 彌勒寺 in Iksan 益山, a new city to which the capital of Baekje later moved. Silla constructed Hwangnyongsa 皇龍寺 in the heart of Gyeongju 慶州. The early seventh-century Mireuksa was built on a huge site on which three temples were placed in juxtaposition according to the Buddhist doctrine stating that Maitreya (Mireuk in Korean), the Future Buddha, would come to the world to save all living beings through three sermons. It is said that Mireuksa covered a land area of 165,000 square meters and was home to as many as three thousand monks. Hwangnyongsa was founded in 570 CE and covered an area of 80,000 square meters. A nine-story wooden pagoda was built at its center. This wooden pagoda rose 80 meters and had stairs inside that led to the top floor. It served as an observatory to view the city. Construction of temples by the royal houses drove the development of technology and improved the quality of Korean architecture overall, not to mention advancing Buddhist architecture.

According to Mahayana Buddhism, which is the mainstream of Korean Buddhism, the whole universe consists of three thousand worlds, which means near infinity, and one Buddha presides over each of these three thousand worlds. Buddhism has expanded from the belief in the one and only Buddha Shakyamuni to the belief in three thousand Buddhas. In particular, Mahayana doctrine emphasizes the “Path of the bodhisattva,” a key teaching of Mahayana ethics, which says “Seek enlightenment above, transform sentient beings below.” Countless bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Samantabhadra became popular and were venerated as second only to Buddha Shakyamuni. Also, in Central Asia and China, indigenous deities were added to the Buddhist pantheon, and these native gods became objects of worship in Korea as well. As a result, Central Asian Luminous Kings, the Daoist gods of the Big Dipper’s seven stars, and the Korean Mountain Spirit, not to mention many other Buddhist deities, all became objects of worship in Korea.

Buddhist temples in Korea necessarily included image halls for multiple Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other deities. According to the principle of “One World, One Buddha,” or the existence of one Buddha at a time, a single building should enshrine only one object of worship, requiring that a temple have various buildings for worship. During the Joseon 朝鮮 period (1392–1910), when Confucianism was espoused by the ruling class and the elite literati-bureaucrats severely suppressed Buddhism, the Buddhist community in an effort to ensure its own survival unified all beliefs in different Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The distinctions between Buddhist sects were removed, and buildings for a number of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other deities were built on the premises of one single temple.

Located in the southern part of the Korean peninsula, Tongdosa 通度寺 has sixteen buildings in total for worship: five separate buildings for five Buddhas including Shakyamuni, Amitabha, Bhaishajyaguru, Vairochana, and Maitreya; four buildings for bodhisattvas and arhats including Avalokiteshvara, Kshitigarbha, and the Arhats; and six building for other deities including Chilseong 七星 (the Daoist Gods of the Seven Stars of the Big Dipper), Dokseong 獨聖 (Hermit Sage), Sansin 山神 (Mountain Spirit), the Four Heavenly Kings, and more.

Korean Buddhism prohibited the marriage of monks and established an obligation to live an austere, celibate life. Although a Buddhist sect that permits the marriage of monks came into being in the twentieth century, celibate monks still dominate the Buddhist community in Korea and are considered morally superior among laypeople. Temples, therefore, are monasteries where monks who renounced the world reside, study, and meditate.

The basic rule at a temple is “one room, one monk.” For this reason, a temple needs as many rooms as the number of monks residing there in addition to facilities like a kitchen, dining hall, bathing area, and toilets. A number of buildings for common use are also required, including a lecture hall to study and discuss sutras, a prayer hall for all monks to chant together, and a hall to practice Seon 禪 (Ch. Chan , Jp. Zen ) or meditation. It has been general practice in traditional Korean architecture to assign one function to each building. As the residences for monks, dining hall, lecture hall, prayer hall, and meditation hall were each separately constructed as independent buildings, the area for monks alone could include some ten buildings. Korean Buddhist architecture was bigger and more dignified than secular architecture. In fact, monasteries were in no way inferior to royal palaces in leading contemporaneous architecture. Numerous Buddhist temples were built during the Joseon period even in the face of the heavy political and economic suppression of Buddhism. The tradition of large scale, ornamented buildings, which was established in the early stage when Buddhism was first introduced to Korea, still continues today.

A temple is a unified premises consisting of a prayer section for laypeople and a monastic section for resident monks. According to Mahayana tradition, the prayer section requires a number of buildings for various objects of worship (Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other deities), and under the tradition of ascetic living, the monastic quarters need multiple buildings, some for eating and sleeping and others for practicing the faith. This is the reason Korean Buddhist temples consist of so many independent buildings. Accordingly, although it is important to make each building impressive, the relationship between buildings within a temple complex has even great significance. Architectural concerns such as the integration and separation of the prayer and monastic sections, the hierarchical distinctions between buildings dedicated to Buddhas and those for subordinate deities, and the association between the interior spaces within buildings and outside spaces between buildings are truly complex issues that are governed by the religious and sectarian tradition of each temple.

Contrary to the European tradition in which materials and building techniques clearly differed between religious and secular structures, Korean Buddhist architecture is not significantly different from that of administrative buildings or common residences. Ancient temples in Egypt and medieval churches in Europe are exquisite, imposing stone edifices, which contrast with ordinary residences made of wood. Korean Buddhist structures, on the other hand, were wooden buildings just like ordinary houses. Construction techniques that were developed for Buddhist architecture were also applied to secular buildings and the technological gap between the two remained narrow. Accordingly, in the Korean architectural tradition, the plan and construction of Buddhist architecture represent characteristics of Korean architecture in general.

The main parts of a building are the stone base, the timber column-and-beam skeleton, and the heavy pitched roof with overhanging eaves. Once a site is selected, the ground is rammed hard and the stone foundation is laid. This platform functions as the support for a row of columns and keeps the wooden structure from rotting due to infiltration of ground moisture into the wooden structure. The corners of the foundation are reinforced with stones, bricks, or tiles. Such stone bases with elaborate facings were generally used for Buddhist structures.

The wooden structure of Korean buildings is composed of framing with vertical columns and horizontal beams. The heavy weight of the roof is transmitted to the beams which in turn distribute the load to the columns and the ground. The columns are connected by lintels which together frame the walls. Spaces within the framework are filled with clay or wood to form a wall or are fitted with windows or doors to provide light and access. For windows and doors of Buddhist structures, a wooden frame decorated with carved floral patterns is covered with translucent Korean paper. Such windows and doors function as barriers that allows air to pass while reducing the effects of cold and heat from outside.

Brackets—supporting elements that are both functional and decorative—are placed on top of the column heads below the eaves. On the brackets are small columns that form a frame for the roof. Rafters of about ten centimeters in diameter are densely laid on the roof-frame to make a sloping roof. The roof is finished by laying tiles on its inclined surfaces. The roof tiles are a type of fired earthenware that make the entire building structurally stable by compressing the frame with their heavy weight while also protecting the building from rain and snow. Korean roof tiles come in convex and concave pairs. Concave tiles are shaped like a quarter cylinder and convex tiles are semicircular in profile. Concave tiles are laid first while convex tiles are placed across the joints between the concave tiles, affording perfect waterproofing for the roof. Specially manufactured roof tile ends are used along the edge of the eaves. Concave and convex roof tile ends are all attached with angled sides so that rainwater can be channeled away from the building. The angled sides of the roof tile ends are decorated. On Buddhist structures, decorative designs that symbolize Buddhism, such as the lotus and phoenix, were stamped on the angled sides. On the peak of the roof, large ornamental tiles called chimi 鴟尾 in Korean crowned the ends of the main roof ridge. This special type of roof tile resembles the tail of an imaginary fish or wings of a bird.

Korean wooden structures were extremely vulnerable to fire. Most were destroyed during war or by accidental fires. Although some buildings have been rebuilt, it is difficult to restore them to their original state. Once they catch fire, major structural components such as columns and beams burn quickly and the whole building collapses. Only the foundation and its stone or clay facing remain along with the roof tiles. Much of the original structure of many European buildings ruined in wars or by fire remain standing for extraordinarily long periods of time because they were made of stone, but the remains of ruined Korean structures are flattened, as can be witnessed at many historic sites. Most artifacts excavated from such ruins are roof tiles, which are fire-resistant. Roof tile ends decorated with exquisitely impressed designs have been discovered in large numbers and displayed in museums.

Unlike wooden buildings in Europe, Korean wooden buildings have long extended eaves in delicately curved lines, which are very impressive. These cantilevered eaves project out from the beams that support the rafters. A special system called gongpo 栱包 (wooden bracket system used to support the heavy tiled roofs at the ends of the eaves) was devised to make the eaves extend in a beautifully curved line. Placed between the heads of the columns and the roof frame, the gongpo disperses the weight to the beams and columns by transmitting the vertical load from the rafters. Elaborate multi-cluster wooden brackets on the heads of the columns create a single structure themselves, which is the most characteristic of all exterior components of Korean structures. Gongpo are also important ornamental components often bearing carved lotus and cloud designs.

At the center of the interior space, Buddhist images are enshrined on top of a wooden altar. This altar is also called the sumidan 須彌壇 as it symbolizes Mount Sumeru, which is regarded as the center of the Buddhist universe. On the ceiling directly above the sumidan hangs a separate house-shaped canopy called a datjip 닫집 in Korean, which serves as a roof for the Buddhist statues enshrined on the altar. The interior of the datjip is filled with sculptures in the shape of a dragon, phoenix, and clouds to represent Buddhist heaven. Buddhist architecture does not divide the interior of a building into compartments but treats it as a single space.

The walls and ceiling are adorned with painted images of Buddha, heavenly beings, and various symbolic motifs such as lotuses. This was meant by the Koreans to create a splendid and magnificent Buddhist paradise. The five basic colors used in Korean architecture are red, yellow, blue, black, and white. The coloring technique is systematic and follows a specific set of rules. In addition to serving as interior and exterior decoration, applied paint protects the wooden building against rotting.

Cave temples and stupas are archetypes of early Buddhist architecture. Caves were natural places for monks who had entered the Buddhist priesthood to practice austerity, and stupas were places for lay devotees to pray. Originally, the stupa, which means “burial mound for enlightened beings” in Sanskrit, was a mound that enshrined relics of the Buddha Shakyamuni and was worshiped as the symbol of the Buddha. China received the tradition of the stupa in the form of the high-storied building from India through Central Asia. Chinese pagodas were mainly built with bricks, but in Korea stone was the preferred material for constructing pagodas. Although both wooden and brick pagodas were also constructed in Korea, most Korean pagodas were built from stone and represent an architectural type distinguishable from the Chinese brick pagodas and Japanese counterparts made of wood.

Cave temples were developed on the Deccan Plateau in India. The earliest examples were created by cutting into sandstone rock to create spaces for Buddhist monks to stay. As visits to monks by lay devotees increased over time, caves for worship were also created, promoting the development of cave temple complexes. In regions where Buddhism spread, constructing a cave temple was regarded as the greatest way of accumulating merit. It soon created an international boom for hollowing out cave temples. This architectural form developed in Ajanta and Nashik in India, spread through Bamiyan and Kizil in Central Asia, and traveled to China, where the cave temples of Dunhuang 敦煌 and Yungang 雲崗 were built. Korea, too, aspired to construct cave temples after Buddhism was first introduced to the peninsula. However, the major rock type which covers the land surface of Korea is granite, which is too hard to cut into. In India and China, cave temples were comparatively easy to construct because the bedrock was much softer limestone, sandstone, and mudstone. Seokguram Grotto 石窟庵, the representative example of Korean cave temples, constructed in the eighth century, is in fact a stone chamber artificially built with stone and covered with a dome.

Although many cave temples were built, most temples were free-standing complexes with proper monks’ quarters. Also, at the initial stage, worship of Buddhist images was not yet introduced, and the stupa was the sole object of devotion. Around the second century BCE, Buddhist statues in the form of human figures appeared in the Gandhara and Mathura regions of India, and such statues became established as objects of worship. It was only natural that Buddhist statues in realistic human form eventually replaced the abstract symbol of the stupa as the central object of worship. This led to the need for the construction of a new building to enshrine Buddhist statues. Because Buddhist sculptures are covered in very expensive gilding, the image hall came to be called the “golden hall.”

The image hall itself became an object of worship because of the Buddhist statues enshrined within. The pagoda standing outside the image hall continued to be an object for a different, more abstract worship. Accordingly, ancient temples comprised an image hall and pagoda together, and the architectural form of the Buddhist temple complex was determined entirely by the relationship between the image hall and the pagoda.

Each of the ancient kingdoms of Korea had its own architectural layout for temples. For example, the architectural type of Goguryeo was “one pagoda, three image halls,” with one pagoda surrounded by image halls on three sides. Baekje adopted the “one pagoda and one image hall” model in which a pagoda, image hall, and lecture hall were placed along a shared axis. In Silla, the “twin pagodas” type, in which two pagodas were located in front of the image hall, was preferred.

Around the tenth century, the Seon School (Kr. Seonjong 禪宗), or Meditation School, was introduced to the Korean peninsula. It was received with enthusiasm by the Korean Buddhist community and was established as the major sect of Korean Buddhism going forward. The Seon School rejected existing icons and freed itself from the existing architectural patterns. Stupa worship, or the “cult of relics,” began to weaken, and this naturally made the pagoda lose importance. Buddhist pagodas became smaller in size and were pushed to the periphery of temple compounds away from the center. Temples without pagodas that have only an image hall quickly became the mainstream model.

Religious architecture in Europe focuses upon the building itself. That is, architecture is a shrine or a church. Buddhist architecture in Korea, on the other hand, is a set of buildings, where a building functions like a single room. For example, the Pantheon in Rome is a religious building and also a piece of religious architecture that enshrines gods. A Buddhist temple in Korea has as few as five and as many as sixty buildings and all these together are considered one architectural whole. The relationship between the buildings and their orientation to the natural topography are essential architectural characteristics. In other words, Korean architecture can be defined as a relationship between buildings and topography rather than as a building itself. This relationship can be considered as an architectural layout or plan. It has taken on diverse forms for a number of reasons, such as when the temple was founded, where the temple is situated, and the sect and religious lineage to which the temple belongs.

Temples founded in ancient times followed strict standards because they were built mostly in capital cities with state support. The “one pagoda, three image halls,” “one pagoda and one image hall,” and “twin pagodas” layouts mentioned earlier are representative architectural plans of ancient temples. These three types all share a common feature in that the perimeter was surrounded by long cloisters forming a border with neighboring sites, which was entirely appropriate for an urban setting. Cloisters composed of a line of buildings make sense due to the flat topographical conditions of a city, enabling temples to be built in standard form.

After the medieval period—particularly during the Joseon period when Buddhism was suppressed—Buddhist temples in the cities were demolished by force and disappeared. Only those deep in the mountains survived. Generous contributions from powerful elites were no longer provided and temples faced financial hardship. Accordingly, inefficient structures like long cloisters disappeared and instead freer architectural arrangements better suited to the irregular, mountainous topography developed. Although the buildings of new temples were generally smaller than those of the past, their number increased to accommodate the beliefs of various schools of Buddhism. The architecture of syncretic Buddhism was more suitable for sloping terrain. Breaking away from geometric layouts, a more organic plan came into being and became the established tradition of Buddhist architecture of Korea.

By the early ninth century, five important sects of Buddhism had been established in Korea. Afterward, Seon Buddhism was introduced in the late ninth and tenth centuries and nine core schools of Seon Buddhism emerged. During the Goryeo 高麗 period (918–1392), when Buddhism was the state religion, the religion reached its apex and some twenty sects flourished. In the thirteenth century, Lamaism, a form of Esoteric Buddhism, was introduced to Korea from Yuan 元 (1279–1368) China. Each of these sects had its own scriptures and teachings, its own main Buddha, and its own view of the universe. It was only natural that the architectural models, which symbolize spiritual principles, should differ among the various types of Buddhism.

For example, temples associated with the Pure Land School, which emphasized a belief in a Buddhist paradise (or Buddha land 佛國土), created an architectural form centered on the external space surrounded by buildings. The inner courtyard of the temple itself was regarded as a representation of the Western Paradise. Temples associated with the Dharma-Character School (Kr. Beopsang jong , Ch. Faxiang zong 法相宗), which promoted Buddhist precepts in religious practice, adopted a strict arrangement of gate-pagoda-stone lantern-image hall-Buddhist statues on a shared axis. Seon temples, on the other hand, were free from such specific constraints. Some were of unprecedented architectural layout with two pagodas placed both in front and behind the image hall. Some followed no architectural pattern at all.

Temples of the Doctrinal School (Kr. Gyojong 敎宗) took a different stance. While temples associated with the Doctrinal School regarded image and lecture halls as important locations for worship and for studying sutras, respectively, Seon emphasized mediation rooms and monks’ living quarters as spaces for religious practice and therefore constructed monastery buildings with spaces for such activities. As advocates for the Doctrinal School and Esoteric Buddhism tend to decorate temples magnificently, they emphasized color and decorative designs. Seon Buddhism, in contrast, regarded all decoration as nothing but emptiness, and emphasized extremely minimal ornament.

The Korean peninsula is small in size with a land area of only 220,000 square kilometers. Its topography is folded into many mountains and valleys, both large and small, making communications between regions difficult and thereby allowing folk cultures peculiar to each region to develop. In particular, the traditions of the Three Kingdoms that coexisted in the early centuries of the development of Buddhism persisted as cultural differences in later history. For example, many buildings in the region of the former Baekje kingdom, which has vast plains, sprawl horizontally, while many of those in the mountainous region of the former Silla kingdom are very vertical.

This discussion has shown that the diversity found in Korean Buddhist architecture developed through the ages, influenced by topography, religious schools, and regional traditions. Although relatively few Buddhist temples remain today, each extant example has unique architectural characteristics resulting from this complex matrix of factors.

* This essay is adapted from a text first published in English by Kim Bongryol in the exhibition catalogue The Smile of Buddha: 1600 Years of Buddhist Art in Korea (Brussels: Bozarbooks and Bai, 2008), 89–99. The publication of the current version has been coordinated by Lee Jae-jeong and Yang Sumi at the National Museum of Korea. It was edited by Keith Wilson and Sunwoo Hwang at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. The copyright belongs to Bozarbooks and Bai, Brussels.

View of stone pillar bases of the West Image Hall, Mireuksa temple site. Korea, Japanese Occupation period, 1917. Original image dry plate photograph. National Museum of Korea, pan 23141

1050 Independence Ave. SW Washington, DC 20013 202.633.1000

© 2024 Smithsonian Institution

- Terms of Use

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Buddhism and buddhist art.

Portrait of Shun'oku Myōha

Unidentified artist Japanese

Fasting Buddha Shakyamuni

Reliquary in the Shape of a Stupa

Standing Buddha Offering Protection

Buddha Maitreya (Mile)

Buddha Maitreya (Mile) Altarpiece

Buddha Offering Protection

Head of Buddha

Buddha, probably Amitabha

Pensive bodhisattva

Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion

Buddha Shakyamuni or Akshobhya, the Buddha of the East

Enthroned Buddha Attended by the Bodhisattvas Avalokiteshvara and Vajrapani

The Bodhisattva Padmapani Lokeshvara

Buddha Vairocana (Dari)

Buddha Amoghasiddhi with Eight Bodhisattvas

Death of the Historical Buddha (Nehan-zu)

Cup Stand with the Eight Buddhist Treasures

Seated Buddha

Vidya Dehejia Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

February 2007

The fifth and fourth centuries B.C. were a time of worldwide intellectual ferment. It was an age of great thinkers, such as Socrates and Plato, Confucius and Laozi. In India , it was the age of the Buddha, after whose death a religion developed that eventually spread far beyond its homeland.

Siddhartha, the prince who was to become the Buddha, was born into the royal family of Kapilavastu, a small kingdom in the Himalayan foothills. His was a divine conception and miraculous birth, at which sages predicted that he would become a universal conqueror, either of the physical world or of men’s minds. It was the latter conquest that came to pass. Giving up the pleasures of the palace to seek the true purpose of life, Siddhartha first tried the path of severe asceticism, only to abandon it after six years as a futile exercise. He then sat down in yogic meditation beneath a bodhi tree until he achieved enlightenment. He was known henceforth as the Buddha , or “Enlightened One.”

His is the Middle Path, rejecting both luxury and asceticism. Buddhism proposes a life of good thoughts, good intentions, and straight living, all with the ultimate aim of achieving nirvana, release from earthly existence. For most beings, nirvana lies in the distant future, because Buddhism, like other faiths of India, believes in a cycle of rebirth. Humans are born many times on earth, each time with the opportunity to perfect themselves further. And it is their own karma—the sum total of deeds, good and bad—that determines the circumstances of a future birth. The Buddha spent the remaining forty years of his life preaching his faith and making vast numbers of converts. When he died, his body was cremated, as was customary in India.

The cremated relics of the Buddha were divided into several portions and placed in relic caskets that were interred within large hemispherical mounds known as stupas. Such stupas constitute the central monument of Buddhist monastic complexes. They attract pilgrims from far and wide who come to experience the unseen presence of the Buddha. Stupas are enclosed by a railing that provides a path for ritual circumambulation. The sacred area is entered through gateways at the four cardinal points.

In the first century B.C., India’s artists, who had worked in the perishable media of brick, wood, thatch, and bamboo, adopted stone on a very wide scale. Stone railings and gateways, covered with relief sculptures, were added to stupas. Favorite themes were events from the historic life of the Buddha, as well as from his previous lives, which were believed to number 550. The latter tales are called jatakas and often include popular legends adapted to Buddhist teachings.

In the earliest Buddhist art of India, the Buddha was not represented in human form. His presence was indicated instead by a sign, such as a pair of footprints, an empty seat, or an empty space beneath a parasol.

In the first century A.D., the human image of one Buddha came to dominate the artistic scene, and one of the first sites at which this occurred was along India’s northwestern frontier. In the area known as Gandhara , artistic elements from the Hellenistic world combined with the symbolism needed to express Indian Buddhism to create a unique style. Youthful Buddhas with hair arranged in wavy curls resemble Roman statues of Apollo; the monastic robe covering both shoulders and arranged in heavy classical folds is reminiscent of a Roman toga. There are also many representations of Siddhartha as a princely bejeweled figure prior to his renunciation of palace life. Buddhism evolved the concept of a Buddha of the Future, Maitreya, depicted in art both as a Buddha clad in a monastic robe and as a princely bodhisattva before enlightenment. Gandharan artists made use of both stone and stucco to produce such images, which were placed in nichelike shrines around the stupa of a monastery. Contemporaneously, the Kushan-period artists in Mathura, India, produced a different image of the Buddha. His body was expanded by sacred breath ( prana ), and his clinging monastic robe was draped to leave the right shoulder bare.

A third influential Buddha type evolved in Andhra Pradesh, in southern India, where images of substantial proportions, with serious, unsmiling faces, were clad in robes that created a heavy swag at the hem and revealed the left shoulder. These southern sites provided artistic inspiration for the Buddhist land of Sri Lanka, off the southern tip of India, and Sri Lankan monks regularly visited the area. A number of statues in this style have been found as well throughout Southeast Asia.

The succeeding Gupta period, from the fourth to the sixth century A.D., in northern India, sometimes referred to as a Golden Age, witnessed the creation of an “ideal image” of the Buddha. This was achieved by combining selected traits from the Gandharan region with the sensuous form created by Mathura artists. Gupta Buddhas have their hair arranged in tiny individual curls, and the robes have a network of strings to suggest drapery folds (as at Mathura) or are transparent sheaths (as at Sarnath). With their downward glance and spiritual aura, Gupta Buddhas became the model for future generations of artists, whether in post-Gupta and Pala India or in Nepal , Thailand , and Indonesia. Gupta metal images of the Buddha were also taken by pilgrims along the Silk Road to China .

Over the following centuries there emerged a new form of Buddhism that involved an expanding pantheon and more elaborate rituals. This later Buddhism introduced the concept of heavenly bodhisattvas as well as goddesses, of whom the most popular was Tara. In Nepal and Tibet , where exquisite metal images and paintings were produced, new divinities were created and portrayed in both sculpture and painted scrolls. Ferocious deities were introduced in the role of protectors of Buddhism and its believers. Images of a more esoteric nature , depicting god and goddess in embrace, were produced to demonstrate the metaphysical concept that salvation resulted from the union of wisdom (female) and compassion (male). Buddhism had traveled a long way from its simple beginnings.

Dehejia, Vidya. “Buddhism and Buddhist Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/budd/hd_budd.htm (February 2007)

Further Reading

Dehejia, Vidya. Indian Art . London: Phaidon, 1997.

Mitter, Partha. Indian Art . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Additional Essays by Vidya Dehejia

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Hinduism and Hindu Art .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ Recognizing the Gods .” (February 2007)

- Dehejia, Vidya. “ South Asian Art and Culture .” (February 2007)

Related Essays

- Chinese Buddhist Sculpture

- Cosmic Buddhas in the Himalayas

- Life of the Buddha

- Tibetan Buddhist Art

- Zen Buddhism

- Chinese Hardstone Carvings

- Daoism and Daoist Art

- East Asian Cultural Exchange in Tiger and Dragon Paintings

- Hinduism and Hindu Art

- Internationalism in the Tang Dynasty (618–907)

- Jain Sculpture

- Japanese Illustrated Handscrolls

- Kings of Brightness in Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Art

- Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th Century)

- Kushan Empire (ca. Second Century B.C.–Third Century A.D.)

- Mauryan Empire (ca. 323–185 B.C.)

- The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-Central Thailand

- Music and Art of China

- Nepalese Painting

- Nepalese Sculpture

- Pre-Angkor Traditions: The Mekong Delta and Peninsular Thailand

- Recognizing the Gods

- Shunga Dynasty (ca. Second–First Century B.C.)

- Tang Dynasty (618–907)

- Tibetan Arms and Armor

- Wang Hui (1632–1717)

- China, 1000–1400 A.D.

- China, 1–500 A.D.

- China, 500–1000 A.D.

- Himalayan Region, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Himalayan Region, 500–1000 A.D.

- Japan, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Korea, 500–1000 A.D.

- South Asia, 1–500 A.D.

- South Asia: North, 500–1000 A.D.

- South Asia: South, 500–1000 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Southeast Asia, 500–1000 A.D.

- 10th Century A.D.

- 11th Century A.D.

- 12th Century A.D.

- 13th Century A.D.

- 14th Century A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- 1st Century A.D.

- 1st Century B.C.

- 20th Century A.D.

- 21st Century A.D.

- 2nd Century A.D.

- 2nd Century B.C.

- 3rd Century A.D.

- 3rd Century B.C.

- 4th Century A.D.

- 4th Century B.C.

- 5th Century A.D.

- 5th Century B.C.

- 6th Century A.D.

- 7th Century A.D.

- 8th Century A.D.

- 9th Century A.D.

- Amoghasiddhi

- Ancient Greek Art

- Ancient Roman Art

- Andhra Pradesh

- Avalokiteshvara

- Cartography

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Gilt Bronze

- Gilt Copper

- Gupta Period

- Hellenistic Period

- Himalayan Region

- Kushan Period

- Monasticism

- Relic / Reliquary

- Relief Sculpture

- Religious Art

- Sancai Glaze

- Sculpture in the Round

- Southeast Asia

- Uttar Pradesh

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Divinity” by Denise Leidy

- 82nd & Fifth: “Pensive” by Soyoung Lee

- The Artist Project: “Thomas Struth on Chinese Buddhist sculpture”

- Connections: “Relics” by John Guy

- Our Selections

- About NEXT IAS

- Director’s Desk

- Advisory Panel

- Faculty Panel

- General Studies Courses

- Optional Courses

- Current Affairs Program (CA-VA)

- Mentorship Program (AIM)

- Interview Guidance Program

- Postal Courses

- Prelims Test Series

- Mains Test Series (GS & Optional)

- ANUBHAV (All India Open Mock Test)

- Daily Current Affairs

- Current Affairs MCQ

- Monthly Current Affairs Magazine

- Previous Year Papers

- Down to Earth

- Kurukshetra

- Union Budget

- Economic Survey

- Download NCERTs

- NIOS Study Material

- Beyond Classroom

- Toppers’ Copies

- Student Portal

TABLE OF CONTENTS

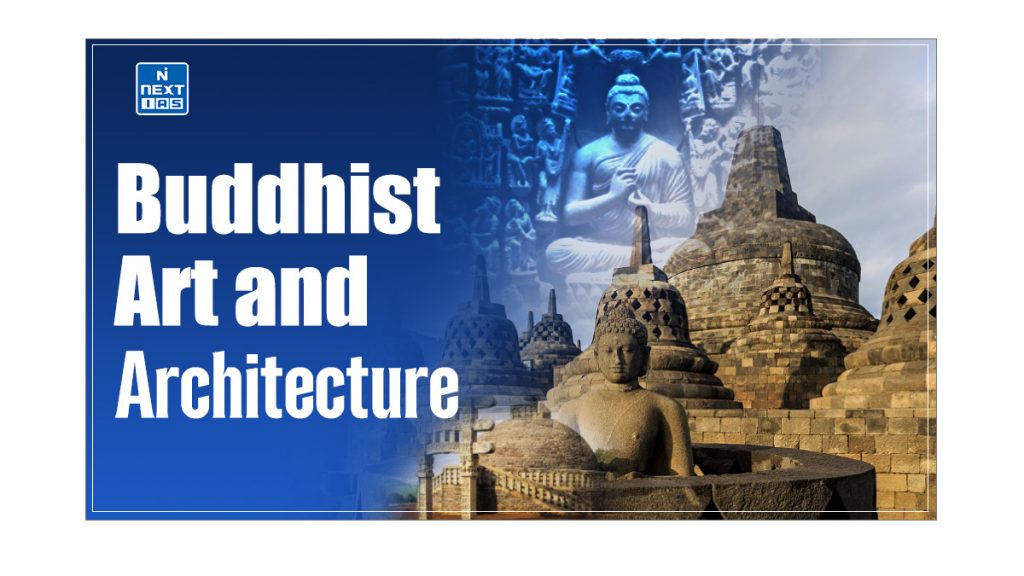

Buddhist art and architecture.

Buddhist art and architecture encompass the various artistic and structural forms created to represent and support Buddhist practices, including stupas, chaityas, and viharas. These forms are significant as they reflect the evolution of Buddhist teachings and cultural exchanges across Asia. This article aims to study in detail the origins, development, and impact of Buddhist art and architecture throughout history.

About Buddhism

- Buddhism, one of the world’s major religions, was founded in India in the 6th century BCE by Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha.

- Rooted in the teachings of the Buddha, Buddhism centres on the path to enlightenment through understanding the Four Noble Truths and following the Eightfold Path, which guides ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom.

- A fundamental tenet of Buddhism is the belief in the impermanence of all things and the cessation of suffering through the renunciation of desire and attachment.

- Buddhism’s focus on compassion, meditation, and the pursuit of wisdom has profoundly shaped Asia’s spiritual and cultural landscape.

- Its teachings inspire millions worldwide, offering a path to inner peace and liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth.

Read our detailed article on Buddhism and Buddhist Literature.

- Buddhist art and architecture represent an integral part of Buddhism’s cultural and religious heritage, reflecting its rich history and evolving practices.

- Buddhist art, which originated from the early aniconic phase to the development of elaborate stupas, chaityas, and viharas, visually embodies the core teachings and principles of Buddhism.

- This art form not only serves as a medium for religious expression but also plays a crucial role in disseminating and preserving Buddhist philosophy.

Origins of Buddhist Art and Architecture

- Buddhist art and architecture originated in India around the 3rd century BCE, evolving from aniconic representations to symbolic and, later, anthropomorphic depictions.

- Initially, Buddhist art avoided direct representations of the Buddha, focusing instead on symbols such as the lotus, stupa, and Dharma wheel to signify his presence and teachings.

- This aniconic phase is exemplified by the early stupas and rock-cut caves, which served as important sites for meditation and rituals.

- With the spread of Buddhism, particularly under the patronage of Emperor Ashoka, art began to include more direct representations of the Buddha and significant events from his life.

- The architectural focus shifted to the construction of stupas, chaityas (prayer halls), and viharas (monastic quarters), each in the religious and communal life of Buddhist monks and lay followers.

- This formative period laid the groundwork for the rich and diverse tradition of Buddhist art that continued to develop across Asia.

Early Buddhist Art

- Buddhist Art refers to the diverse range of artistic expressions associated with Buddhism, encompassing sculptures, paintings, architecture, and decorative arts that depict the life, teachings, and symbols of the Buddha.

- Early Buddhist Art primarily employed symbolic representations rather than physical images of the Buddha, reflecting a period of aniconism.

- Prominent symbols included the Dharma Wheel, Bodhi Tree, and Lotus Flower, each embodying key aspects of Buddhist teachings and practices, which have been discussed in detail in the following section.

Aniconic Phase

- In the initial phase of Buddhist art, the Buddha was represented indirectly through symbols rather than images.

- During this period, known as the aniconic phase, he avoided depicting the Buddha’s physical form, focusing instead on symbols that conveyed his teachings and presence.

- This approach aligned with the early Buddhist emphasis on avoiding idol worship.

Major Symbols

- The Dharma Wheel (Dharmachakra) represents the Buddha’s teachings and the cycle of birth and rebirth;

- The Bodhi Tree signifies the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment;

- These symbols were integral to Buddhist art and were focal points for meditation and worship.

Gandhara School

- Gandhara Art, influenced by Greco-Roman styles, is known for its realistic representation and detailed sculptural forms.

- Notable examples include Buddha statues, intricate reliefs, and stupas, which showcase a blend of Hellenistic and Buddhist artistic traditions.

Mathura School

- Mathura Art is characterised by its indigenous Indian styles and emphasis on divine imagery, reflecting traditional Indian aesthetic values.

- Buddha images, sculptures, and distinctive stupa designs are prominent examples, highlighting the region’s rich contribution to early Buddhist art.

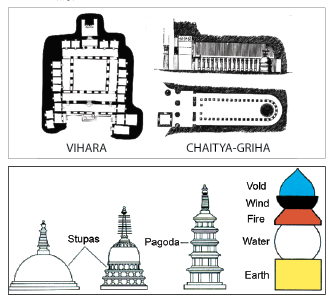

Buddhist Architecture in India

- Buddhist architecture in India encompasses the structures built for the practice and veneration of Buddhism.

- Buddhist architecture in India includes stupas, chaityas, viharas, and monastic complexes, which serve as centres for worship, meditation, and communal living and reflect Buddhism’s spiritual and cultural values.

- Buddhist architecture in India is designed to embody the principles of Buddhist teachings and support the monastic lifestyle.

- The Stupa is a significant architectural form in Buddhist art, designed to house relics of the Buddha or revered monks.

- Traditionally, it is a dome-shaped structure with a central chamber that contains the relics, often surrounded by a circular path for circumambulation.

- The stupa’s design symbolises the Buddha’s enlightenment and the cosmos, with its mound representing the cosmic axis and the circular path symbolising the cycle of life and rebirth.

- A Chaitya is a distinctive Buddhist prayer hall or shrine characterised by its barrel-vaulted roof and a stupa at one end.

- The interior of a chaitya often features an apsidal shape, creating a space conducive to meditation and worship.

- The design emphasises a harmonious space for communal worship and reflection, with the stupa as the focal point of devotion.

- The Vihara is an early form of a Buddhist monastery that typically includes an open courtyard surrounded by individual cells or rooms for monks.

- These structures were initially designed to provide shelter during the rainy season, facilitating the monastic practice of retreat and study.

- The layout of viharas reflects the communal and contemplative nature of early Buddhist monastic life, emphasising simplicity and functionality.

Monastic Complexes

- Monastic complexes are expansive religious centres that include chaityas, viharas, and other facilities for the monastic community.

- These complexes, such as those found at Nalanda and Takshashila, are significant in Buddhist monastic life as they provide space for meditation, teaching, and communal living.

- The layout of these complexes, integrating educational, residential, and worship spaces, highlights the organised structure of Buddhist monastic institutions and their role in disseminating Buddhist teachings.

Examples of Indian Buddhist Architecture

- The stupas of Sanchi and Amravati, the chaityas of Ajanta and Ellora, and the viharas of Nalanda represent some of the finest examples of Indian Buddhist architecture.

- These sites showcase advanced architectural and artistic techniques and reflect Buddhism’s spiritual and cultural significance in ancient India.

- Each site offers unique insights into the evolution and integration of Buddhist architectural forms into the broader landscape of Indian art and culture.

Influence of Buddhist Art and Architecture

- In Central Asia, Buddhist motifs were integrated into the art of the Silk Road, while in Southeast Asia, the construction of stupas and intricate carvings in countries like Thailand and Myanmar were inspired by earlier Indian styles.

- East Asian regions, including China and Japan, adopted and adapted Buddhist art forms, such as the construction of cave temples and the portrayal of Buddhist deities, reflecting the deep cultural exchange facilitated by Buddhism.

- This enduring influence extends beyond the Buddhist world, impacting global art movements by introducing Buddhist symbolism and aesthetic elements into diverse artistic expressions.

- Buddhist art’s adaptability and universal appeal have ensured its relevance in historical and modern contexts.

In conclusion, Buddhist art and architecture offer profound insights into Buddhism’s spiritual and cultural dimensions. These artistic and architectural forms have been crucial in disseminating Buddhist teachings, from the early aniconic symbols to the grandeur of stupas and monastic complexes. The influence of Buddhist art extends beyond India, impacting artistic traditions across Asia and continuing to inspire contemporary art and global cultural movements. This enduring legacy underscores Buddhist art’s significance in understanding Buddhism’s historical and spiritual journey.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is buddhist art and architecture.

Buddhist art and architecture refers to the visual and structural expressions that developed around the teachings of Buddhism, including sculptures, paintings, stupas, and monasteries.

What are the key features of Buddhist art?

Buddhist art features symbolic representations of the Buddha, such as mudras and the lotus, and depictions of Bodhisattvas.

What are the art forms of Buddhism?

Buddhism’s main art forms include stupas (monumental structures housing relics), cave temples (like Ajanta and Ellora), sculptures of Buddha and Bodhisattvas, and paintings depicting Buddhist narratives.

Latest Article

Dual Administration in Bengal

Land Revenue Policy: Permanent, Mahalwari & Ryotwari System

Nuclear Reactors

India’s Nuclear Research Program

भारत में प्राकृतिक वनस्पति : प्रकार, वर्गीकरण, महत्व और अधिक

मैडेन-जूलियन ऑसिलेशन (MJO): विशेषताएँ, चरण और महत्व

Explore Categories

- Art and Culture

- Disaster Management

- Environment and Ecology

- Important Days

- Indian Economy

- Indian Polity

- Indian Society

- Internal Security

- International Relations

- Science and Technology

Subscribe to our Newsletter!

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agrarian/Rural

- Animal Studies

- Archaeology

- Art and Architecture

- Asian American

- Borderlands

- Central Asia

- Citizenship and National Identity/Nationalism

- Comparative

- Demography/Family

- Digital Methods

- Diplomatic/International

- Economic/Business

- Environmental

- Ethnohistory

- Film Studies

- Food and Foodways

- Historiography/Historical Theory and Method

- Indian Ocean Studies

- Indigenous Studies (except the Americas)

- Intellectual

- Material Culture

- Memory Studies

- Middle East

- Migration/Immigration/Diaspora

- Peace and Conflict

- Popular Culture

- Postcolonial Studies

- Print Culture/History of the Book

- Race and Ethnicity

- Science and Technology

- Southeast Asia

- World/Global/Transnational

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Buddhist art and architecture.

- Sonya S. Lee Sonya S. Lee University of Southern California

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.398

- Published online: 19 November 2020

The art and architecture of Buddhism has shaped the physical and social landscape of Asia for more than two millennia. Images of the Buddha and other Buddhist deities, alongside the physical structures built to enshrine them, are found in practically all corners of the continent, where the religion has enjoyed widespread dissemination. India boasts some of the earliest extant works dating from the 3rd century bce , whereas new images and monuments continue to be made today in many countries in East and Southeast Asia as well as in North America and Europe. Spanning across diverse cultures, Buddhist material culture encompasses a wide range of object types, materials, and settings. Yet the Buddha represented in anthropomorphic form and the stupa that preserves his presence through either bodily relics or symbolic objects remain the most enduring forms through time and space. Their remarkable longevity underscores the tremendous flexibility inherent in Buddhist teaching and iconography, which allows local communities to adapt and reconstitute them for new meanings. Such processes of localization can be understood through close analysis of changes in style, materials, production techniques, and context.

The ubiquity of Buddhist art and architecture across the globe is made possible chiefly by a fundamental belief in religious merits, a concept that encourages believers to do good in order to accumulate positive karma for spiritual advancement. One of the most common forms of action is to give alms and other material objects to the monastic community as well as make offerings to the Buddha, thereby giving rise to active patronage of image-making and scripture production.

- bodhisattva

- cave temple

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Asian History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 18 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Character limit 500 /500

An overview of Buddhist architecture

Buddhism is a religion that respects the environment . Most Buddhists aim to transcend worldly, material desires and establish a close relationship with nature. Disciples could establish and sustain a calm and joyful mind, especially during the Buddha’s lifetime when they frequently resided in very primary and unfinished thatched homes. They were at ease wherever they lived, whether in a suburban neighbourhood, a forest, by the water, in a chilly cave, or under a tree. However, as the number of Buddhist adherents increased, King Bimbisara and a follower of Sudatta suggested that a monastery be constructed , allowing practitioners to congregate in one location and engage in a more organized practice. The Buddha approved for followers to donate to monasteries after giving the idea careful thought and subsequent wholehearted agreement. The Megara-matr-Prasada Lecture Hall, the Bamboo Grove, and the Jetavana Monastery—all of which bear the donor’s Sanskrit name—were built as a result. This marked the start of Indian Buddhist architecture.

Types and Styles of Buddhist Architecture

The hub of cultural activities is frequently a Buddhist temple. From a contemporary perspective, temples can be compared to museums because they house priceless and unique works of art and are, in and of themselves, stunning works of art. They combine architecture, sculpture , painting, and calligraphy-like art museums do. One can find peace and tranquillity in temples because they provide a harmonious environment and a spiritual atmosphere. They are helpful locations for people in distress to unload their burdens, calm their minds, and find peace.

Stupas were the primary type of architectural construction in early China . The hall (or shrine) started to take centre stage in the Sui and Tang dynasties. A stupa, also known as a pagoda, is sometimes referred to as the “high rise” of Buddhist architecture because of its tall, narrow shape that extends upward, sometimes with enormous height. India is where the idea and physical form of the Chinese stupa was developed. A stupa serves as a shrine for the Buddha’s relics, where visitors can then make offerings to the Buddha. The stupa has undergone significant changes in China, where it originally had a relatively straightforward design. These changes and advancements show off the nation’s artistic and architectural prowess. Stupas are built in different sizes, proportions, colours, and imaginative designs while retaining a generally recognizable shape. Although stupas can be found near water, in cities, mountains, or the countryside, they were all built to blend in with and enhance their surroundings. One of the most well-liked styles of architecture in China is the stupa.

Every region’s Buddhist architecture has a distinctive personality due to its varied cultural and natural environments. India and Ceylon share a close architectural resemblance. Similar architecture can be found in Burma, Thailand , and Cambodia , where wood is incorporated into the design of the buildings. The stupas in Java are similar to those in Tibet, which are made of stone and symbolize the nine-layered Mandala (a symbolical circular figure representing the universe and the divine cosmology of various religions: used in meditation and rituals). Large monasteries in Tibet are frequently built on hillsides and resemble European architecture in terms of how the structures are linked to one another to create a kind of street-style arrangement.

It is common practice in China to construct Buddhist temples in the emperor’s palace style, known as “palace architecture.” The main gate and main hall are in the centre, and other facilities, such as the celestial and the abbot’s quarters, are lined up on either side. This layout was created with symmetry in mind. There is a ceremonial bell on one side and a ceremonial drum on the other. A guesthouse for lay visitors and the Yun Shui Hall, where staying monastics can be accommodated, will be located behind this symmetrical line of buildings.

Wood and tile, with the roof tiles painted a particular colour, were used to construct the temple’s ancillary buildings. China has very few palace-style temples that have survived from the early ages because wood is a complex material to preserve over long periods. However, it is a blessing that the Tang-era wooden construction of Fo Guang Temple is still standing. Fo Guang Temple’s main palace-style hall is still remarkably sturdy and pristine, giving us an impression of the era’s opulence. This still-standing temple still features exquisite Tang Dynasty artwork, which includes sculpture, paintings, and murals. This allows us to realize that this period was the pinnacle of Chinese artistic expression. This temple, designated a national treasure, serves as a reminder of China’s glorious period of art and architecture .

The modifications of structure, decoration, and construction techniques that change and evolve through various eras can be seen in Fo Guang Temple and the other temples that have endured through the years—although there are not many. Additionally, they act as the tangible visual memory of a particular time and place, enabling us to study the architectural and cultural history of the area. Despite China’s 5,000-year history, very little of its architecture has been preserved, as was already mentioned. The reason we do not have more standing temples from the early ages to study today is not just because they were built with wood, which is highly flammable and prone to decay. There are other explanations for why there are not many temples left. For instance, some dynasties that gained power around the 16th century mandated the destruction of the essential structures built by the previous dynasty. Alternatively, temples were damaged or even destroyed during various wars and acts of aggression. Regardless of the building materials employed — wood, stone, clay, etc. – Human rivalry made it almost impossible for many temples to endure. Buddhist cave temples, fortunately, were largely safe from human vandalism and weather damage. They are well-preserved and enable the viewing of conventional architecture and historical art.

It is common for contemporary Buddhist temples to copy older designs. For instance, the main shrines of Taiwan’s Fo Guang Shan, the Hsi Lai Temple in the United States, and the Nan Tien Temple in Australia were all modelled after early Chinese architectural styles. The Chinese culture has been introduced and disseminated throughout the world by several Buddhist temples today, in addition to honouring and preserving it.

Cave Temples

The rock cave , or cave temple, and all of the art it contains is the most critical link in Chinese Buddhist art and architecture history. A cave temple is a chamber of varying sizes carved out of a single block of rock, sometimes right up against a cliff face. Many are rather large. Ornate statues, sculptures, and vibrant paintings of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, arhats, and sutras can be found inside the rock caves. 366 C.E. saw the beginning of this artistic practice. E. until the 15th century, it was started by a monk by the name of Le Zun. In some places, enormous carved statues and countless cave temples cover mountainsides. The Dung Huang cave is the most well-known for its magnificent and opulent mural among the numerous cave temples. Longmen Caves in Luoyang, Yungang Caves in Datong, and the Thousand Buddhas Cave in Jinang are a few other well-known caves in China . Due to its enormous size, Yungang Cave is particularly well-known.

The construction of cave temples took place over a long period, spanning several dynasties. Unlike wooden temples, which deteriorate due to exposure to the elements, cave temples are protected by solid rock and thus continue to stand as impressive and imposing reminders of how Buddhism once flourished throughout China. The world has been awed by the beauty and grandeur of the Buddhist artwork found in the caves, which has managed to capture the essence and specifics of the teachings for the enjoyment of all who visit. In the opinion of both artists and archaeologists , this kind of Buddhist architecture is particularly vibrant, lovely, and indicative of how Buddhist art has changed and evolved. They are priceless works of art that have an important place in China’s history of culture, art, and architecture.

The design of secular buildings, especially imperial palaces, has long influenced Chinese temple architecture. This custom is upheld in Nan Tien by the structures and colours used throughout. From a distance, grandiose roofs signify status: the higher the rank, the higher the height and slope. Consequently, the Main Shrine has the tallest and most impressive roof. The emperor in dynastic China only wore yellow items. The yellow temple walls and terracotta roof tiles are significant symbols. Traditional fire protection measures include small mythical creatures lining the roof hips. Back when the entire building would have been made of wood, the fire was a real threat. Even though the roof framing on Nan Tien is mainly made of steel, the painted end beams that extend under the eaves give the impression that the building is made of wood.

Associated with the emperor is the colour red, which is also considered lucky. It was applied to imperial columns, beams, and lintels like at Nan Tien. Palace balustrades were typically made of white marble carved; Nan Tien’s concrete balustrades are made similarly and are painted white.

The prominently raised podium for Buddha or Bodhisattva statues found at the back of each shrine is another feature reminiscent of imperial architecture; it is similar to the throne that the emperor was seated upon in royal audience halls.

As in conventional palace design, Nan Tien’s courtyard plan of less important buildings rising to the most important is directed by axial geometry reflecting an established hierarchy. The Main Shrine serves as the head, the surrounding buildings serve as the arms, and the courtyard serves as the lap in a seated Buddha’s arrangement in the courtyard.

A Buddhist’s journey along the Middle Path to enlightenment is analogous to the progression through the complex, which includes climbing stairs to the Front Shrine, more stairs to the courtyard, and continuing along a central walk to a final set of stairs before the Main Shrine.

Temple compounds typically include a meditation hall, sutra library, and lodging for monks in addition to the shrines dedicated to specific Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. In addition to these, Nan Tien includes other amenities required for day-to-day operation: a museum , a conference room with cutting-edge technology for conferences and simultaneous translation, an auditorium that is well-equipped for large gatherings, a dining hall that serves the general public vegetarian buffet lunches, and Pilgrim Lodge, which provides lodging for both visitors and participants in retreats or celebrations held at Nan Tien.

References:

Rajras: Buddist Architecture in India [online] Available at: https://www.rajras.in/buddhist-architecture-of-india/ [Accessed date: 15 November 2022].

AHTR: Buddist Art and Architecture before 1200 [online] Available at: https://arthistoryteachingresources.org/lessons/buddhist-art-and-architecture-before-1200/ [Accessed date: 14 November 2022].

UCLA Social Science: Buddist Architecture [online] Available at: https://southasia.ucla.edu/culture/architecture/buddhist-architecture/ [Accessed date: 15 November 2022].

Insightsias: Buddist Architecture in India [online] Available at: https://www.insightsonindia.com/indian-heritage-culture/architecture/buddhist-architecture/ [Accessed date: 15 November 2022].

Slideshare: Buddist Architecture in India [online] Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/roopachikkalgi/buddhist-architecture-73527008 [Accessed date: 18 November 2022].

Chan Simon is a fresh architecture school graduate from the University of Juba with a passion for evening the playing field. He is currently a design studio teaching assistant in the architecture department at the School of Architecture, Land Management, Urban and Regional Planning (University of Juba).

Inclusion of arts in public areas

Shanghai West Bund International AI Tower and Plaza by Nikken Sekkei

Related posts.

Evoking Emotion: Colour Theory in the Historic Palaces of Jaipur

Understanding Wars through destroyed Architecture

The Blurring of Formal and Informal Spaces- Seeping Urbanism in India

Things to be considered while designing for the dead

The Lives and Works of Nonconformist Architects: Visionaries Who Redefined Architecture

Sustainable Urban Design: Innovative Architecture Firms Everyone Should Know

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Visual & Material Culture: Southeast Asia & Sri Lanka

Buddhism: Visual & Material Culture: Southeast Asia & Sri Lanka

- General & Introductory

- Themes & Issues

- Online Resources

- Theravada: Main

- Theravada: Primary Texts

- Theravada: Early & Indian Buddhism

- Theravada: Southeast Asia & Sri Lanka

- Theravada: Teachers & Teachings

- Mahayana: Main

- Mahayana: Primary Texts

- Mahayana: China, Mongolia, Taiwan

- Mahayana: Japan, Korea, Vietnam

- Mahayana: Major Thinkers

- Tibet: Main

- Tibet: Topics

- Tibet: Practices

- Tibet: Early Masters & Teachings

- Tibet: Contemporary Masters & Teachings

- Zen: Regions

- Zen: Early Masters & Teachings

- Zen: Contemporary Masters & Teachings

- Zen: The Kyoto School

- Western: Main

- Western: Thinkers & Topics

- Visual & Material Culture: Main

- Visual & Material Culture: Central Asia

- Visual & Material Culture: East Asia

- Visual & Material Culture: South Asia

Southeast Asia | Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam | Indonesia

Myanmar | Sri Lanka | Thailand

Andrea Acri & Peter D. Sharrock (eds.), The Creative South: Buddhist and Hindu Art in Mediaeval Maritime Asia, Volume 1 (2022)

San San May & Jana Igunma, Buddhism Illuminated: Manuscript Art from Southeast Asia (2018)

Gauri Parimoo Krishnan (ed.), Nalanda, Srivijaya and Beyond: Re-exploring Buddhist Art in Asia (2016)

Kimberly Masteller, Masterworks from India and Southeast Asia: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (2016)

D. Christian Lammerts (ed.), Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern and Early Modern Southeast Asia (2015)

Sambit Datta & David Beynon, Digital Archetypes: Adaptations of Early Temple Architecture in South and Southeast Asia (2014)

John Guy et al, Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia (2014)

Gauri Parimoo Krishnan, On the Nalanda Trail: Buddhism in India, China, and Southeast Asia (2013)

Elisabeth A. Bacus, Ian C. Glover, and Peter D. Sharrock (eds.), Interpreting Southeast Asia’s Past: Monument, Image and Text (2008)

Aziz Bassoul, Human and Divine: The Hindu and Buddhist Iconography of Southeast Asian Art from the Claire and Aziz Bassoul Collection (2006)

Fiona Kerlogue, Arts of Southeast Asia (2004)

Pratapaditya Pal, Asian Art at the Norton Simon Museum, Volume 3: Art from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia (2004)

Nandana Chutiwongs, The Iconography of Avalokiteśvara in Mainland South East Asia (2002)

Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk Road (100 BC–1300 AD) (2002)

Marijke J. Klokke, Narrative Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia (2000)

Maud Girard-Geslan (ed.), Art of Southeast Asia, trans. J. A. Underwood (1998)

Daigoro Chihara, Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia (1996)

Philip Rawson, The Art of Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Java, Mali (1990)

George Coedès, The Making of South East Asia, trans. H.M. Wright (1966)

Louis Frédéric, The Art of Southeast Asia: Temples and Sculpture (1965)

M.M. Deneck et al, Indian Sculpture: Masterpieces of Indian, Khmer, and Cham Art (1962)

Bernard Philippe Groslier, The Art of Indochina: Including Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, trans. George Lawrence (1962)

Buddhist temples in Southeast Asia are centers for the preservation of local artistic traditions. Chief among these are manuscripts, a vital source for our understanding of Buddhist ideas and practices in the region. They are also a beautiful art form, too little understood in the West. The British Library has one of the richest collections of Southeast Asian manuscripts, principally from Thailand and Burma, anywhere in the world. It includes finely painted copies of Buddhist scriptures, literary works, historical narratives, and works on traditional medicine, law, cosmology, and fortune-telling. This stunning new book includes over 100 examples of Buddhist art from the Library's collection, relating each manuscript to Theravada tradition and beliefs, and introducing the historical, artistic, and religious contexts of their production. It is the first book in English to showcase the beauty and variety of Buddhist manuscript art and reproduces many works that have never before been photographed.

The study of historical Buddhism in premodern and early modern Southeast Asia stands at an exciting and transformative juncture. Interdisciplinary scholarship is marked by a commitment to the careful examination of local and vernacular expressions of Buddhist culture as well as to reconsiderations of long-standing questions concerning the diffusion of and relationships among varied texts, forms of representation, and religious identities, ideas and practices. The twelve essays in this collection, written by leading scholars in Buddhist Studies and Southeast Asian history, epigraphy, and archaeology, comprise the latest research in the field to deal with the dynamics of mainland and (pen)insular Buddhism between the sixth and nineteenth centuries C.E. Drawing on new manuscript sources, inscriptions, and archaeological data, they investigate the intellectual, ritual, institutional, sociopolitical, aesthetic, and literary diversity of local Buddhisms, and explore their connected histories and contributions to the production of intraregional and transregional Buddhist geographies.

The volume covers monumental arts, sculpture and painting, epigraphy and heritage management across mainland Southeast Asia and as far south as Indonesia. New research on monumental arts includes chapters on the Bayon of Angkor and the great brick temple sites of Champa. There is an article discussing the purpose of making and erecting sacred sculptures in the ancient world and accounts of research on the sacred art of Burma, Thailand and southern China (including the first study of the few surviving Saiva images in Burma), of a spectacular find of bronze Mahayana Buddhas, and of the sculpted bronzes of the Dian culture. New research on craft goods and crafting techniques deals with ancient Khmer materials, including recently discovered ceramic kiln sites, the sandstone sources of major Khmer sculptures, and the rare remaining traces of paint, plaster and stucco on stone and brick buildings. More widely distributed goods also receive attention, including Southeast Asian glass beads, and there are contributions on Southeast Asian heritage and conservation, including research on Angkor as a living World Heritage site and discussion of a UNESCO project on the stone jars of the Plain of Jars in Laos that combines recording, safeguarding, bomb clearance, and eco-tourism development.

The pagodas of Burma, the temples of Angkor, the great Buddhist monument of Borobudur - these achievements of powerful courts and rulers are part of a broad artistic tradition including textiles, applied arts, vernacular architecture, and village crafts. Covering Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Burma, and the Philippines, Fiona Kerlogue examines the roots and development of the arts of this distinctive region from prehistory to the present day. Broadly chronological, the book traces the different religions that have shaped the region's historic cultures - Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity - finishing with an exploration of the arts of the postcolonial period. With nearly 200 illustrations, over 100 in color, a glossary of names and places, and suggestions for further reading, the book is a comprehensive introduction to the arts and culture of Southeast Asia.

Leedom Lefferts & Sandra Cate, Buddhist Storytelling in Thailand and Laos: The Vessantara Jataka Scroll at the Asian Civilisations Museum, trans. Wajuppa Tossa (2012)

Anne-Valérie Schweyer, Ancient Vietnam: History, Art and Archaeology (2011)

Vittorio Roveda & Sothon Yem, Preah Bot: Buddhist Painted Scrolls in Cambodia (2010)

Claude Jacques & Michael Freeman, Ancient Angkor (2009)

Joyce Clark (ed.), Bayon: New Perspectives (2007)

Claude Jacques, The Khmer Empire: Cities and Sanctuaries from the 5th to the 13th Century, trans. Tom White (2007)

Helen Ibbitson Jessup, Art & Architecture of Cambodia (2004)

Emmanuel Guillon, Hindu-Buddhist Art of Vietnam: Treasures from Champa, trans. Tom White (2001)

Somkiart Lopetcharat, Lao Buddha: The Image and Its History (2000)

Eleanor Mannikka, Angkor Wat: Time, Space, and Kingship (2000)

Helen Ibbitson Jessup & Thierry Zephir (eds.), Sculpture of Angkor and Ancient Cambodia: Millennium of Glory (1997)

Ann H. Unger & Walter Unger (eds.), Pagodas, Gods and Spirits of Vietnam (1997)

Marc Riboud, Angkor: The Serenity of Buddhism (1993)

Jean Boisselier, Trends in Khmer Art, ed. & trans. Natasha Eilenberg & Melvin Elliott (1989)

Madeleine Giteau, Khmer Sculpture and the Angkor Civilization (1965)

John N. Miksic & Anita Tranchini, Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas (2017)

Jan Fontein, Entering the Dharmadhatu: A Study of the Gandavyūha Reliefs of Borobudur (2012)

Julie Gifford, Buddhist Practice and Visual Culture: The Visual Rhetoric of Borobudur (2011)

Natasha Reichle, Violence and Serenity: Late Buddhist Sculpture from Indonesia (2007)

I.G.N. Anom (ed.) & UNESCO, The Restoration of Borobudur (2005)

Ann R. Kinney, Marijke J. Klokke, and Lydia Kieven, Worshiping Siva and Buddha: The Temple Art of East Java (2003)

Paul Mus, Barabudur: Sketch of a History of Buddhism Based on Archaeological Criticism of the Texts (1998)

Louis Frédéric & Jean-Louis Nou, Borobudur (1996)

Marijke J. Klokke & Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer (eds.), Ancient Indonesian Sculpture (1994)

Roy Adams, Borobudur in Photographs: Past and Present (1990)

Jan Fontein (ed.), The Sculpture of Indonesia (1990)

R.P. Soekmono, J.G. de Casparis, and Jacques Dumarçay, Borobudur: Prayer in Stone (1990)

Rudi Badil & Nurhadi Rangkuti (eds.), The Hidden Foot of Borobudur (1989)

Pauline L. Scheurleer & Marijke J. Klokke, Divine Bronze: Ancient Indonesian Bronzes from A.D. 600 to 1600 (1988)

Luis O. Gómez & Hiram W. Woodward (eds.), Barabudur: History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument (1981)

A.J. Bernet Kempers, Ageless Borobudur: Buddhist Mystery in Stone. Decay and Restoration. Mendut and Pawon. Folklife in Ancient Java, trans. Surya Green (1979)

Jacques Dumarçay, Borobudur, trans. Michael Smithies (1978)

Jan Fontein et al (eds.), Ancient Indonesian Art of the Central and Eastern Javanese Periods (1971)

A.J. Bernet Kempers, Ancient Indonesian Art (1959)

W.F. Stutterheim, Studies in Indonesian Archaeology (1956)

With vivid photography and insightful commentary, this travel pictorial shines a light on the Buddhist art and architecture of Borobudur. The glorious ninth-century Buddhist stupa of Borobudur--the largest Buddhist monument in the world--stands in the midst of the lush Kedu Plain of Central Java in Indonesia, where it is visited annually by over a million people. Borobudur contains more than a thousand exquisitely carved relief panels extending along its many terraces for a total distance of more than a kilometer. These are arranged so as to take the visitor on a spiritual journey to enlightenment, and one ascends the monument past scenes depicting the world of desire, the life story of Buddha, and the heroic deeds of other enlightened beings--finally arriving at the great circular terraces at the top of the structure that symbolizes the formless world of pure knowledge and perfection.