Aviation Phraseology: An In-Depth Analysis of FAA and ICAO Standards

Aviation phraseology is a crucial component of air traffic communication, ensuring safety and clarity between pilots and air traffic controllers (ATC). This specialized language minimizes ambiguity, enabling clear, concise communication. It is governed by various regulatory bodies, with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) being two primary authorities. Despite their shared goal of maintaining safety, their phraseology standards have notable differences. This article provides an in-depth analysis of aviation phraseology, highlighting the distinctions between FAA and ICAO protocols.

What Is Aviation Phraseology?

Definition and importance.

Aviation phraseology refers to the standardized language used in radio communications between pilots and air traffic controllers. Its primary purpose is to facilitate precise, unambiguous communication to prevent misunderstandings that could compromise safety. Pilots and controllers worldwide must adhere to specific phraseology to ensure that critical information is exchanged correctly.

Standardization in Aviation

Standard phraseology allows for a global understanding of communication, regardless of language barriers or regional accents. It encompasses terms, phrases, and procedures that convey intentions, instructions, and responses. This uniformity is especially vital during emergencies, as it ensures a predictable and clear exchange of information.

The Role of the FAA and ICAO in Phraseology

Faa: federal aviation administration.

The FAA is responsible for regulating all aspects of civil aviation in the United States. It sets phraseology standards used by pilots and air traffic controllers within U.S. airspace. The FAA’s phraseology emphasizes brevity and directness, with a focus on reducing airtime to manage busy communication frequencies effectively.

ICAO: International Civil Aviation Organization

ICAO, a United Nations specialized agency, establishes global aviation standards, including phraseology. Its regulations aim to ensure uniform communication across international borders. ICAO phraseology is more expansive, allowing for clearer communication when non-native English speakers are involved, which can help avoid misunderstandings in diverse air traffic environments.

Key Differences Between FAA and ICAO Phraseology

1. terminology and phrase structure.

One of the key distinctions between FAA and ICAO phraseology lies in their approach to terms and phrases used in communication.

- FAA Focus on Conciseness : The FAA, now aligned with ICAO standards in many areas, aims to keep communications as brief as possible, especially in high-traffic airspaces like those in the United States. For example, in 2010, the FAA adopted the ICAO phrase “Line up and wait” (LUAW) to replace its earlier term “Taxi into position and hold” (TIPH). This change helped streamline instructions while maintaining global standardization Federal Aviation Administration Federal Aviation Administration .

- ICAO Emphasis on Standardization and Clarity : ICAO’s global approach prioritizes clear and uniform communication to accommodate the diverse linguistic backgrounds of pilots and controllers. Phrases like “Runway vacated” are designed to minimize ambiguity, ensuring precise understanding of runway status across different regions Federal Aviation Administration . This focus on standardization aims to enhance safety, particularly in international airspaces where clear communication is critical to avoid misunderstandings.

Despite the shift toward uniformity, differences in communication styles still exist, reflecting each organization’s approach to managing air traffic in their respective operational environments.

2. Phraseology for Takeoff and Landing

The phraseology used by the FAA and ICAO during takeoff and landing operations has nuanced differences, which are particularly important for pilots navigating between these systems.

- Takeoff Instructions : Both FAA and ICAO use the term “Cleared for takeoff” to indicate that an aircraft is authorized to begin its departure roll. However, ICAO practices often emphasize providing detailed information as part of the clearance, such as wind direction and speed, which enhances situational awareness. For example, an ICAO instruction might include “Wind 320 at 10, cleared for takeoff.” The FAA may include similar details, but its emphasis is typically on brevity when radio frequencies are congested (Federal Aviation Administration , IVAO Documentation Library) . This approach aims to keep communications efficient in high-traffic airspace, such as that found in the United States (Savant Aero) .

- Landing Clearances : For landing, both FAA and ICAO use the phrase “Cleared to land,” but with differing levels of detail. The FAA might issue a straightforward instruction like “Cleared to land, runway 18,” focusing on maintaining flow and minimizing radio congestion (Skybrary, Savant Aero) . ICAO, in contrast, may include additional context in its instructions, such as specific runway conditions or traffic information, particularly if conditions differ from the norm or visibility is reduced. For example, an ICAO clearance might include “Runway 24, wet, braking action medium, cleared to land” (IVAO Documentation Library) .

These differences reflect each organization’s focus: the FAA prioritizes efficiency and succinct communication to manage the dense air traffic within the United States, while ICAO emphasizes comprehensive, detailed communication to account for the diverse international pilots and environments they serve (Federal Aviation Administration, Savant Aero) . Understanding these distinctions is critical for pilots, especially those who fly internationally, to ensure clear communication and safe operations.

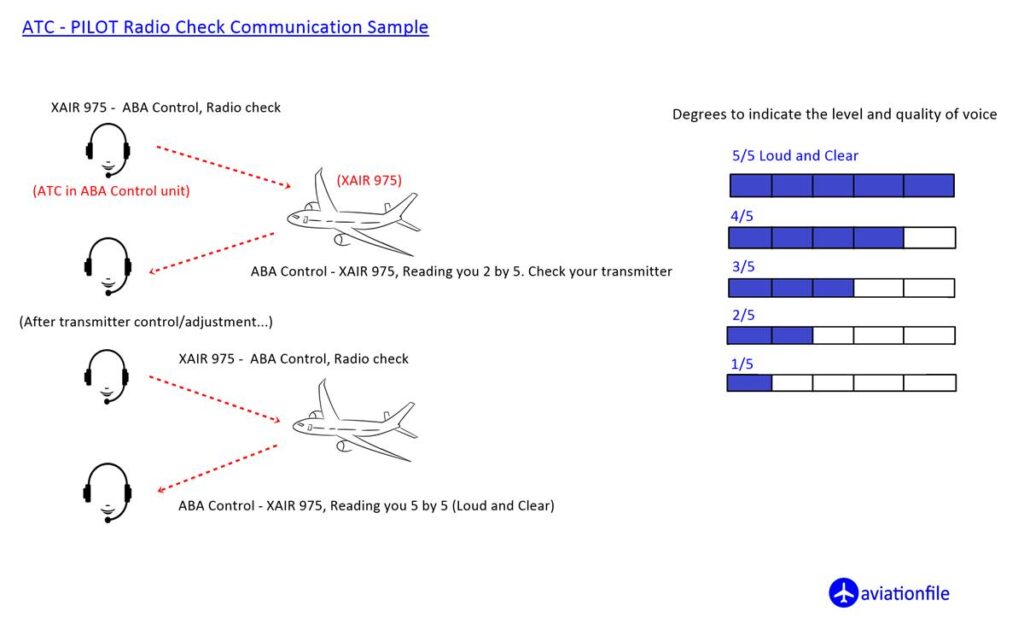

3. Use of Readback and Acknowledgments

Readback requirements, where pilots repeat back instructions to confirm understanding, also differ between the two systems.

- FAA Approach : The FAA mandates readbacks primarily for critical clearances like takeoff, landing, and altitude assignments. It aims to keep radio communication brief, relying on context and situational awareness for other communications.

- ICAO Approach : ICAO requires readbacks for a broader range of instructions, including heading assignments and altitude changes, ensuring a higher level of confirmation for all critical information. This practice is especially beneficial in international settings where linguistic variations can create challenges.

Impact of Phraseology Differences on Pilots

Adapting to different standards.

Pilots operating internationally need to adapt to both FAA and ICAO phraseology standards. This adjustment can be challenging, as they must switch between concise and more detailed communication styles depending on the airspace they are in. Miscommunication or incorrect phraseology usage can result in confusion, delays, or even safety risks.

Training and Proficiency Requirements

Airlines and aviation authorities prioritize training pilots and air traffic controllers to maintain proficiency in both sets of standards. Emphasis is placed on understanding regional differences to ensure that pilots can communicate effectively in any environment. This training is essential for maintaining global aviation safety and preventing incidents related to phraseology confusion.

Challenges and Future Directions

Harmonization efforts.

The aviation community has made efforts to harmonize FAA and ICAO phraseology standards. These efforts aim to create more consistent communication practices, particularly as international flights become increasingly common. However, regional variations in air traffic density, language proficiency, and procedural preferences still present challenges to achieving full harmonization.

Technology and Phraseology Evolution

Advancements in communication technology, such as digital data links and voice recognition, are gradually supplementing traditional voice communication. These technologies could reduce the reliance on exact phraseology by providing an additional layer of verification. However, standardized phraseology will remain a core element of safety, especially in complex or emergency situations.

Aviation phraseology is a vital tool in maintaining safety and efficiency in air traffic communication. While both the FAA and ICAO share the goal of clear and effective communication, their differences in phraseology reflect the diverse needs of domestic and international aviation. Understanding these differences is crucial for pilots, controllers, and aviation stakeholders, as it allows for safe adaptation across various regions. As aviation continues to evolve, the balance between standardized global communication and regional adaptability will remain a key focus, shaping the future of air traffic management.

You May Also Like

Planes don’t fly over Tibet, but why?

Aileron of an Airplane

How are Airport Locations Determined?

Airport Research Needs: Cooperative Solutions -- Special Report 272 (2003)

Chapter: 5 conclusions and recommendations, 5 conclusions and recommendations.

T he key findings of this report are summarized in this chapter. The committee believes that the findings

Justify the creation of a national research program focused on the needs of airport operators;

Reveal how such a program can play a role in helping airport operators meet the many demands of federal agencies, state governments, local communities, and airport users; and

Provide guidance on governing, funding, and administering an airport research program.

JUSTIFICATION FOR A RESEARCH PROGRAM FOCUSED ON AIRPORTS

Some 5,000 airports scattered across the country are open to public use in the United States, including more than 500 that offer airline service. They vary in size from more than 50 square miles to a few dozen acres and accommodate aircraft ranging from 500-seat jet airliners to single-engine props. They form a key component of the country’s heavily used aviation system. Unlike the centralized air traffic control enterprise, which is run almost entirely by the federal government, the nation’s airports are a collection of independent entities owned and operated by thousands of mostly public agencies.

The diversity and decentralization of the airport system are strengths. Competition among airports for the business of airlines and other aircraft users prompts efficiencies and innovations in products, processes, and services. At the same time, individual airports are elements of regional and national transportation networks; they are interconnected and dependent on one another. For aviation users—whether airline passengers, shippers, or general aviation (GA) operators—the vast airport network with its many origin and destination points is what makes the nation’s aviation system so useful.

Recognizing the importance of building and maintaining a nationally integrated aviation system, the federal government has long played an important role in providing assistance to thousands of airports run by state and local governments. During the past three decades, it has granted more than $30 billion to operators for improvements in runways and taxiways, terminal facilities, noise mitigation, safety equipment, security, and air navigation and guidance systems. Most of the revenues to fund these investments stem from federal taxes and other levies on aviation users maintained in the Airport and Airway Trust Fund.

To protect the large federal investment in the nation’s airport infrastructure and ensure its safe and efficient use, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has established various standards governing major aspects of the design, construction, maintenance, and operations of airport facilities. In supporting the development and implementation of these standards, FAA sponsors research on topics ranging from pavement durability to noise modeling and mitigation.

Yet, from the standpoint of airport operators, different research needs are apparent. For example, an increase in an airport’s operations must be carried out without significantly increasing noise, air pollution, or other environmental impacts. Security must be strengthened without unduly burdening and possibly driving away users. Federal restrictions on how airports can generate revenues from landing fees and other user charges—restrictions that accompany most federal grants—must be balanced against demands by state and municipal owners that airports seek out new revenue sources to become self-supporting. In the end, it is up to the airport operators themselves to find ways to meet these many demands.

Operators face a growing challenge in responding to these demands. New agencies with jurisdiction over airports, such as the Transportation Security Administration, are imposing new requirements. Others, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and its state counterparts, have gradually expanded their authority into the realm of airport planning, construction, and operations. Thus, what may appear to be straightforward requirements from the perspective of a single agency can result in many uncertainties and problems for airport operators. At the moment, operators do not have a research capability to address these uncertainties and solve the resulting problems.

The airport research enterprise does not currently provide a means for operators to cooperate among themselves and with other interested parties to

find solutions to shared problems or to seek new ideas to improve airport operations. The federal government has much at stake in ensuring that such research is undertaken and that it is of the highest quality. Airports with fewer problems are more likely to use their resources efficiently and to require less federal assistance. They are more likely to be able to respond effectively to the requirements of federal agencies—whether to strengthen security, protect the environment, or increase capacity. And they are more likely to be able to meet the demands of airport users, which will ultimately benefit travelers and shippers depending on safe, secure, and efficient air service.

Cooperative research activities confer many other benefits that can be difficult to gauge. The National Highway Cooperative Research Program (NCHRP) and the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) have demonstrated that regular collaboration of practitioners, public officials, researchers, and technical experts can provide opportunities for the exchange of information and ideas. Moreover, practitioners who are actively involved in research gain skills and expertise that strengthen the industry’s professional capacity and help attract talented individuals to the field. Of course, research performed at universities is essential for training students and interesting them in the airport management and engineering professions.

UNIQUE ROLE OF AN AIRPORT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

The mission of a national airport cooperative research program (ACRP) must be clear and well articulated so that the program complements, and does not duplicate or detract from, existing research activities. An ACRP, unlike any current program, will provide an opportunity to address problems that

Many operators share but that tend to be too costly or complex for a single operator or a small group of operators to research;

Receive limited attention because of a lack of funding or incompatibility with the mission and institutional requirements of federal agencies and others that traditionally perform airport-related research; and

Can be researched with a reasonable expenditure of time and effort to yield results that can be readily implemented by airport operators and users.

The following are examples of airport needs in several common problem areas. They illustrate the kinds of research questions that could be addressed through a national ACRP.

Operations and safety

What is a safe and efficient speed for escalators and moving sidewalks in airport environments that are often crowded with hurrying passengers carrying luggage?

How are proposed changes in air traffic control and area navigation rules, such as terminal instrument procedures, likely to affect the configuration, placement, and capacity of airport taxiways and runways? What effects are these changes likely to have on overall airport capacity?

Maintenance

What methods are most suitable for choosing among alternative maintenance products and practices for use under different airport conditions?

What tools do operators have—and how effective are they—for monitoring the condition of assets, prioritizing maintenance activity, and managing maintenance personnel and contractors?

Design of infrastructure and equipment

How do airports currently use FAA’s advisory circulars? Which circulars are most urgently in need of updating to give airports better design guidance?

To what extent have changes in the dimensions, controllability, and visibility of modern aircraft been accounted for in FAA design standards for taxiway geometrics, signage visibility, and wingtip clearances, and what modifications of these standards are warranted?

Finance and administration

What experience do airport operators have in this country and abroad in using design–build–finance techniques for expediting construction of new facilities? What have been the positive and negative results of these efforts? What can be learned from experiences in public works and other modes of transportation?

What are the emerging challenges that airports face, in light of heightened security concerns, in recruiting and retaining qualified personnel and reducing workplace stress? What can be learned from the practices of other industries facing similar challenges?

What changes in aircraft types, dimensions, and uses can be expected in the medium and near terms, and how can these changes be accommodated in capital planning for airport facilities?

What changes in demand-forecasting methodologies are needed to better assess future facility requirements given the uncertainties now affecting the entire commercial aviation sector?

Environment

What alternative aircraft deicing methods and materials are available? How well do they balance the needs for safety assurance, environmental protection, affordability, and compatibility with operational requirements?

What are the data and modeling requirements to analyze emissions of air toxics associated with health risks at airports in a manner that is scientifically credible and useful in decision making?

What changes in the current regulatory framework for airports would be required to streamline the planning and environmental documentation process for critically needed airport improvements?

What cost-effective changes in terminal designs and features (e.g., “way-finding” signs) are available to facilitate security processing, avoid crowding, and expedite the movement of passenger traffic through terminals?

How can passenger and baggage flows be modeled accurately to assist in the longer-term infrastructure planning for the design and location of explosive detection systems and for deployment of security personnel?

Although this list is not comprehensive, it reveals a diversity of research needs. Specific research interests will undoubtedly vary by airport size, location, use patterns, and other factors. Operators of GA airports, for instance, may be more interested in research on the kinds of asphalt pavements found on short-field runways than on the more rigid concrete structures used for paving runways that can handle large commercial jets. Likewise, northern airports will have a greater interest in research on snow- and ice-control methods and materials, while commercial-service airports will be the most interested in research to improve the efficiency of passenger and cargo flows.

The wide scope of research needs suggests that a cooperative research program must be responsive, rigorous, objective, and capable of involving practitioners and researchers with expertise from many disciplines. Insights gained from reviewing the experiences of NCHRP and TCRP indicate that how a program is governed, financed, and managed will have a large bearing on these capabilities.

PROGRAM GOVERNANCE, FINANCE, AND MANAGEMENT: LESSONS FROM NCHRP AND TCRP

A research program’s overall design and organizational characteristics have a fundamental influence on the research needs addressed, how the research is carried out, the quality of the results, and the extent to which the results are applied. The committee’s review of NCHRP and TCRP suggests that the following characteristics will be especially important in guiding the establishment of an airport research program.

Airport operators must integrate the demands of multiple federal agencies, state and local governments, and airport users. The challenges and problems they face result in research needs and priorities that differ from those making the demands. Operators, therefore, must have a primary role in setting the research agenda, defining the expected products of research, and ensuring the timeliness and applicability of the research results. In doing so, they must cooperate closely with the federal agencies and users of airports, all of whom have an interest in ensuring that the operators succeed.

The experiences of NCHRP and TCRP suggest that an ACRP will require a strong and committed governing board. The board should consist of top executives from a cross section of the nation’s airports as well as representatives from federal agencies, industry organizations, and airport users. The governing board must define the research priorities and ensure overall quality and relevance of the research. It must articulate expected research products and assist with dissemination of research results. Finally, it must coordinate with other research programs that have complementary functions.

The federal government, the private sector, and airport operators collectively spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year on airport-related research and technology development. The committee did not examine whether these funds are allocated appropriately or have been successful in achieving their objectives. However, the study indicates that airports do not currently have a way to fund urgent, short-term research to meet their needs. While the immediate and near-term problems of airport operators are not intrinsically more important than those being addressed by established research programs, they differ in nature and urgency, and thus they deserve explicit attention.

The experiences of NCHRP and TCRP suggest the importance of having finances dedicated to cooperative research. Dedicated funding can provide a base that is sufficiently large to address a range of research needs and reliable enough to sustain interest in the program. A program that is limited to a narrow set of research problems because of limited finances is likely to become marginalized. Airport operators in particular must view the program as a dependable source of ideas and information. They must have a sense of ownership of the program—a commitment to ensuring that the program addresses airport needs and is run efficiently. Because the ultimate beneficiaries of the research will be airport users, financing of the program through aviation user fees can provide these critical stakeholder connections.

NCHRP and TCRP are managed by TRB. Their experience demonstrates that the organization managing the research program must provide more than accounting and administrative services. It must refine the research needs, establish objective means of selecting competent researchers, ensure that research results are technically sound, and disseminate the results widely within the appropriate communities. It must have experience in managing a research program covering a number of disciplines.

Both NCHRP and TCRP use competitively selected contractors to perform the work. Contract-based research offers the greatest flexibility in utilizing the varied expertise and facilities needed for a diverse research portfolio. It also requires competent managers to develop requests for proposals, screen competing researchers with regard to their qualifications, and administer the contracts. The managers must be able to draw on both technical experts and practitioners to define projects, participate in merit review to select capable researchers to perform the work, and peer-review the quality and applicability of the results. Above all, the management organization must be viewed as impartial, independent, and committed to undertaking quality research and disseminating the results.

MODEL ACRP AND NEXT STEPS

Congress requested this study of the desirability of a national cooperative research program for airports. In so doing, it asked for an assessment of the applicability of the financing and administrative approaches used by NCHRP and TCRP. The committee believes that these programs offer an organizational

model well suited to meeting the research needs of airport operators and proposed means of governing, financing, and managing an ACRP in Chapter 4 . A proposal for a trial program is outlined in Box 5-1 . It embodies the key characteristics discussed above:

The program would be governed and guided by the top managers from a cross section of the nation’s airports in collaboration with representatives of federal agencies, airport users, and others.

It would be financed with revenues derived from aviation users. Such financing would bring about a research agenda that is focused on producing solutions with direct application to airport problems and would thus prompt a strong commitment to the program on the part of the airport and aviation communities.

Its management would be structured to ensure that the research products meet the highest applicable standards and are accessible to users.

This model is derived from the NCHRP and TCRP structures. It provides a first step toward creating an ACRP. The experience of TCRP—established only a decade ago—provides insights into subsequent steps. Convinced of the merits of a cooperative research program, transit agencies took it upon themselves to broaden awareness and build consensus for a cooperative research program. They acted through industry associations to clarify the organizational structure of the desired program, outline a legislative proposal, and mobilize support for it. Top transit managers have remained active in the program since its inception. The nation’s airport operators will need to commit themselves to a similar effort.

TRB Special Report 272 - Airport Research Needs: Cooperative Solutions urges the U.S. Congress to establish a national airport cooperative research program. The committee that produced the report called such a program essential to ensuring airport security, efficiency, safety, and environmental compatibility.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

IMAGES

VIDEO