Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Citation Styles

- Chicago Style

- Annotated Bibliographies

What is a Lit Review?

How to write a lit review.

- Video Introduction to Lit Reviews

Main Objectives

Examples of lit reviews, additional resources.

- Zotero (Citation Management)

What is a literature review?

- Either a complete piece of writing unto itself or a section of a larger piece of writing like a book or article

- A thorough and critical look at the information and perspectives that other experts and scholars have written about a specific topic

- A way to give historical perspective on an issue and show how other researchers have addressed a problem

- An analysis of sources based on your own perspective on the topic

- Based on the most pertinent and significant research conducted in the field, both new and old

- A descriptive list or collection of summaries of other research without synthesis or analysis

- An annotated bibliography

- A literary review (a brief, critical discussion about the merits and weaknesses of a literary work such as a play, novel or a book of poems)

- Exhaustive; the objective is not to list as many relevant books, articles, reports as possible

- To convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic

- To explain what the strengths and weaknesses of that knowledge and those ideas might be

- To learn how others have defined and measured key concepts

- To keep the writer/reader up to date with current developments and historical trends in a particular field or discipline

- To establish context for the argument explored in the rest of a paper

- To provide evidence that may be used to support your own findings

- To demonstrate your understanding and your ability to critically evaluate research in the field

- To suggest previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, and quantitative and qualitative strategies

- To identify gaps in previous studies and flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches in order to avoid replication of mistakes

- To help the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research

- To suggest unexplored populations

- To determine whether past studies agree or disagree and identify strengths and weaknesses on both sides of a controversy in the literature

- Choose a topic that is interesting to you; this makes the research and writing process more enjoyable and rewarding.

- For a literature review, you'll also want to make sure that the topic you choose is one that other researchers have explored before so that you'll be able to find plenty of relevant sources to review.

- Your research doesn't need to be exhaustive. Pay careful attention to bibliographies. Focus on the most frequently cited literature about your topic and literature from the best known scholars in your field. Ask yourself: "Does this source make a significant contribution to the understanding of my topic?"

- Reading other literature reviews from your field may help you get ideas for themes to look for in your research. You can usually find some of these through the library databases by adding literature review as a keyword in your search.

- Start with the most recent publications and work backwards. This way, you ensure you have the most current information, and it becomes easier to identify the most seminal earlier sources by reviewing the material that current researchers are citing.

The organization of your lit review should be determined based on what you'd like to highlight from your research. Here are a few suggestions:

- Chronology : Discuss literature in chronological order of its writing/publication to demonstrate a change in trends over time or to detail a history of controversy in the field or of developments in the understanding of your topic.

- Theme: Group your sources by subject or theme to show the variety of angles from which your topic has been studied. This works well if, for example, your goal is to identify an angle or subtopic that has so far been overlooked by researchers.

- Methodology: Grouping your sources by methodology (for example, dividing the literature into qualitative vs. quantitative studies or grouping sources according to the populations studied) is useful for illustrating an overlooked population, an unused or underused methodology, or a flawed experimental technique.

- Be selective. Highlight only the most important and relevant points from a source in your review.

- Use quotes sparingly. Short quotes can help to emphasize a point, but thorough analysis of language from each source is generally unnecessary in a literature review.

- Synthesize your sources. Your goal is not to make a list of summaries of each source but to show how the sources relate to one another and to your own work.

- Make sure that your own voice and perspective remains front and center. Don't rely too heavily on summary or paraphrasing. For each source, draw a conclusion about how it relates to your own work or to the other literature on your topic.

- Be objective. When you identify a disagreement in the literature, be sure to represent both sides. Don't exclude a source simply on the basis that it does not support your own research hypothesis.

- At the end of your lit review, make suggestions for future research. What subjects, populations, methodologies, or theoretical lenses warrant further exploration? What common flaws or biases did you identify that could be corrected in future studies?

- Double check that you've correctly cited each of the sources you've used in the citation style requested by your professor (APA, MLA, etc.) and that your lit review is formatted according to the guidelines for that style.

Your literature review should:

- Be focused on and organized around your topic.

- Synthesize your research into a summary of what is and is not known about your topic.

- Identify any gaps or areas of controversy in the literature related to your topic.

- Suggest questions that require further research.

- Have your voice and perspective at the forefront rather than merely summarizing others' work.

- Cyberbullying: How Physical Intimidation Influences the Way People are Bullied

- Use of Propofol and Emergence Agitation in Children

- Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza's 'Ethics'

- Literature Review Tutorials and Samples - Wilson Library at University of La Verne

- Literature Reviews: Introduction - University Library at Georgia State

- Literature Reviews - The Writing Center at UNC Chapel Hill

- Writing a Literature Review - Boston College Libraries

- Write a Literature Review - University Library at UC Santa Cruz

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: Zotero (Citation Management) >>

- Last Updated: Sep 16, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.elac.edu/Citation

Boatwright Memorial Library

- Chicago/Turabian

- AP (Associated Press)

- APSA (Political Science)

- ASA & AAA (Soc/Ant)

- ACS (Chemistry)

- Harvard Style

- SBL (Society of Biblical Literature)

- EndNote Web

- Help Resources

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Literature Reviews

- Citation exercises This link opens in a new window

What is a Literature Review?

The literature review is a written explanation by you, the author, of the research already done on the topic, question or issue at hand. What do we know (or not know) about this issue/topic/question?

- A literature review provides a thorough background of the topic by giving your reader a guided overview of major findings and current gaps in what is known so far about the topic.

- The literature review is not a list (like an annotated bibliography) -- it is a narrative helping your reader understand the topic and where you will "stand" in the debate between scholars regarding the interpretation of meaning and understanding why things happen. Your literature review helps your reader start to see the "camps" or "sides" within a debate, plus who studies the topic and their arguments.

- A good literature review should help the reader sense how you will answer your research question and should highlight the preceding arguments and evidence you think are most helpful in moving the topic forward.

- The purpose of the literature review is to dive into the existing debates on the topic to learn about the various schools of thought and arguments, using your research question as an anchor. If you find something that doesn't help answer your question, you don't have to read (or include) it. That's the power of the question format: it helps you filter what to read and include in your literature review, and what to ignore.

How Do I Start?

Essentially you will need to:

- Identify and evaluate relevant literature (books, journal articles, etc.) on your topic/question.

- Figure out how to classify what you've gathered. You could do this by schools of thought, different answers to a question, the authors' disciplinary approaches, the research methods used, or many other ways.

- Use those groupings to craft a narrative, or story, about the relevant literature on this topic.

- Remember to cite your sources properly!

- Research: Getting Started Visit this guide to learn more about finding and evaluating resources.

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (IUPUI Writing Center) An in-depth guide on organizing and synthesizing what you've read into a literature review.

- Guide to Using a Synthesis Matrix (NCSU Writing and Speaking Tutorial Service) Overview of using a tool called a Synthesis Matrix to organize your literature review.

- Synthesis Matrix Template (VCU Libraries) A word document from VCU Libraries that will help you create your own Synthesis Matrix.

Literature Reviews: Overview

This video from NCSU Libraries gives a helpful overview of literature reviews. Even though it says it's "for graduate students," the principles are the same for undergraduate students too!

Literature Review Examples

Reading a Scholarly Article

- Reading a Scholarly Article or Literature Review Highlights sections of a scholarly article to identify structure of a literature review.

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article (NCSU Libraries) Interactive tutorial that describes parts of a scholarly article typical of a Sciences or Social Sciences research article.

- Evaluating Information | Reading a Scholarly Article (Brown University Library) Provides examples and tips across disciplines for reading academic articles.

- Reading Academic Articles for Research [LIBRE Project] Gabriel Winer & Elizabeth Wadell (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI))

Additional Tutorials and Resources

- UR Writer's Web: Using Sources Guidance from the UR Writing Center on how to effectively use sources in your writing (which is what you're doing in your literature review!).

- Write a Literature Review (VCU Libraries) "Lit Reviews 101" with links to helpful tools and resources, including powerpoint slides from a literature review workshop.

- Literature Reviews (UNC Writing Center) Overview of the literature review process, including examples of different ways to organize a lit review.

- “Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review.” Pautasso, Marco. “Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review.” PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 9, no. 7, July 2013, p. e1003149.

- Writing the Literature Review Part I (University of Maryland University College) Video that explains more about what a literature review is and is not. Run time: 5:21.

- Writing the Literature Review Part II (University of Maryland University College) Video about organizing your sources and the writing process. Run time: 7:40.

- Writing a Literature Review (OWL @ Purdue)

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliographies

- Next: Citation exercises >>

PSYC 323: Clinical Psychology

- Tips for Searching for Articles

- Tips for Writing a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

Conducting a literature review, organizing a literature review, writing a literature review, helpful book.

- Tests, Measurements, & Counseling Techniques

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Google Scholar

- In Class Activity This link opens in a new window

A literature review is a compilation of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches

Source: "What is a Literature Review?", Old Dominion University, https://guides.lib.odu.edu/c.php?g=966167&p=6980532

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by a central research question. It represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted, and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- Write down terms that are related to your question for they will be useful for searches later.

2. Decide on the scope of your review.

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment.

- Consider these things when planning your time for research.

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

- By Research Guide

4. Conduct your searches and find the literature.

- Review the abstracts carefully - this will save you time!

- Many databases will have a search history tab for you to return to for later.

- Use bibliographies and references of research studies to locate others.

- Use citation management software such as Zotero to keep track of your research citations.

5. Review the literature.

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question you are reviewing? What are the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze the literature review, samples and variables used, results, and conclusions. Does the research seem complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicted studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Are they experts or novices? Has the study been cited?

Source: "Literature Review", University of West Florida, https://libguides.uwf.edu/c.php?g=215113&p=5139469

A literature review is not a summary of the sources but a synthesis of the sources. It is made up of the topics the sources are discussing. Each section of the review is focused on a topic, and the relevant sources are discussed within the context of that topic.

1. Select the most relevant material from the sources

- Could be material that answers the question directly

- Extract as a direct quote or paraphrase

2. Arrange that material so you can focus on it apart from the source text itself

- You are now working with fewer words/passages

- Material is all in one place

3. Group similar points, themes, or topics together and label them

- The labels describe the points, themes, or topics that are the backbone of your paper’s structure

4. Order those points, themes, or topics as you will discuss them in the paper, and turn the labels into actual assertions

- A sentence that makes a point that is directly related to your research question or thesis

This is now the outline for your literature review.

Source: "Organizing a Review of the Literature – The Basics", George Mason University Writing Center, https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/research-based-writing/organizing-literature-reviews-the-basics

- Literature Review Matrix Here is a template on how people tend to organize their thoughts. The matrix template is a good way to write out the key parts of each article and take notes. Downloads as an XLSX file.

The most common way that literature reviews are organized is by theme or author. Find a general pattern of structure for the review. When organizing the review, consider the following:

- the methodology

- the quality of the findings or conclusions

- major strengths and weaknesses

- any other important information

Writing Tips:

- Be selective - Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. It should directly relate to the review's focus.

- Use quotes sparingly.

- Keep your own voice - Your voice (the writer's) should remain front and center. .

- Aim for one key figure/table per section to illustrate complex content, summarize a large body of relevant data, or describe the order of a process

- Legend below image/figure and above table and always refer to them in text

Source: "Composing your Literature Review", Florida A&M University, https://library.famu.edu/c.php?g=577356&p=3982811

- << Previous: Tips for Searching for Articles

- Next: Tests, Measurements, & Counseling Techniques >>

- Last Updated: Oct 10, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://infoguides.pepperdine.edu/PSYC323

Explore. Discover. Create.

Copyright © 2022 Pepperdine University

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

What is the purpose of literature review , a. habitat loss and species extinction: , b. range shifts and phenological changes: , c. ocean acidification and coral reefs: , d. adaptive strategies and conservation efforts: .

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review .

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as yo u go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free!

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

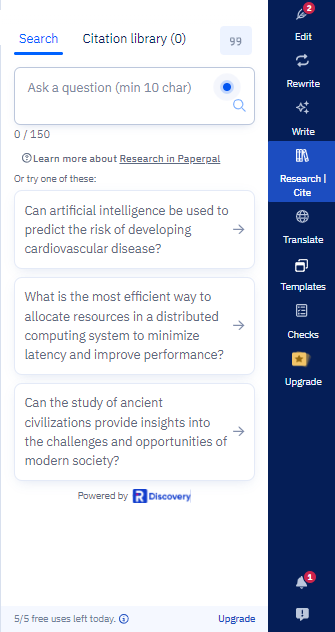

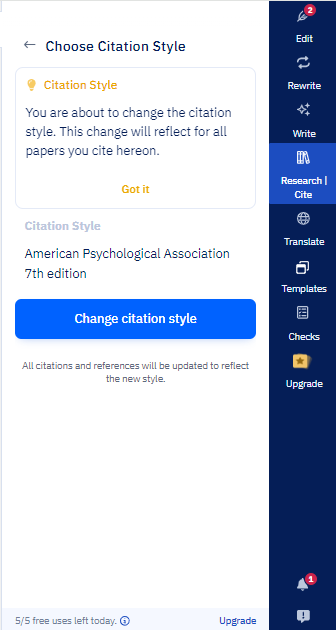

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research | Cite feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface. It also allows you auto-cite references in 10,000+ styles and save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research | Cite” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references in 10,000+ styles into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 22+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, what are the types of literature reviews , what are research skills definition, importance, and examples , what is phd dissertation defense and how to..., abstract vs introduction: what is the difference , mla format: guidelines, template and examples , machine translation vs human translation: which is reliable..., what is academic integrity, and why is it..., how to make a graphical abstract, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison .

Conduct a literature review

What is a literature review.

A literature review is a summary of the published work in a field of study. This can be a section of a larger paper or article, or can be the focus of an entire paper. Literature reviews show that you have examined the breadth of knowledge and can justify your thesis or research questions. They are also valuable tools for other researchers who need to find a summary of that field of knowledge.

Unlike an annotated bibliography, which is a list of sources with short descriptions, a literature review synthesizes sources into a summary that has a thesis or statement of purpose—stated or implied—at its core.

How do I write a literature review?

Step 1: define your research scope.

- What is the specific research question that your literature review helps to define?

- Are there a maximum or minimum number of sources that your review should include?

Ask us if you have questions about refining your topic, search methods, writing tips, or citation management.

Step 2: Identify the literature

Start by searching broadly. Literature for your review will typically be acquired through scholarly books, journal articles, and/or dissertations. Develop an understanding of what is out there, what terms are accurate and helpful, etc., and keep track of all of it with citation management tools . If you need help figuring out key terms and where to search, ask us .

Use citation searching to track how scholars interact with, and build upon, previous research:

- Mine the references cited section of each relevant source for additional key sources

- Use Google Scholar or Scopus to find other sources that have cited a particular work

Step 3: Critically analyze the literature

Key to your literature review is a critical analysis of the literature collected around your topic. The analysis will explore relationships, major themes, and any critical gaps in the research expressed in the work. Read and summarize each source with an eye toward analyzing authority, currency, coverage, methodology, and relationship to other works. The University of Toronto's Writing Center provides a comprehensive list of questions you can use to analyze your sources.

Step 4: Categorize your resources

Divide the available resources that pertain to your research into categories reflecting their roles in addressing your research question. Possible ways to categorize resources include organization by:

- methodology

- theoretical/philosophical approach

Regardless of the division, each category should be accompanied by thorough discussions and explanations of strengths and weaknesses, value to the overall survey, and comparisons with similar sources. You may have enough resources when:

- You've used multiple databases and other resources (web portals, repositories, etc.) to get a variety of perspectives on the research topic.

- The same citations are showing up in a variety of databases.

Additional resources

Undergraduate student resources.

- Literature Review Handout (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

- Learn how to write a review of literature (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Graduate student and faculty resources

- Information Research Strategies (University of Arizona)

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students (NC State University)

- Oliver, P. (2012). Succeeding with Your Literature Review: A Handbook for Students [ebook]

- Machi, L. A. & McEvoy, B. T. (2016). The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success [ebook]

- Graustein, J. S. (2012). How to Write an Exceptional Thesis or Dissertation: A Step-by-Step Guide from Proposal to Successful Defense [ebook]

- Thomas, R. M. & Brubaker, D. L. (2008). Theses and Dissertations: A Guide to Planning, Research, and Writing

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

How do I Write a Literature Review?: #5 Writing the Review

- Step #1: Choosing a Topic

- Step #2: Finding Information

- Step #3: Evaluating Content

- Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- #5 Writing the Review

- Citing Your Sources

WRITING THE REVIEW

You've done the research and now you're ready to put your findings down on paper. When preparing to write your review, first consider how will you organize your review.

The actual review generally has 5 components:

Abstract - An abstract is a summary of your literature review. It is made up of the following parts:

- A contextual sentence about your motivation behind your research topic

- Your thesis statement

- A descriptive statement about the types of literature used in the review

- Summarize your findings

- Conclusion(s) based upon your findings

Introduction : Like a typical research paper introduction, provide the reader with a quick idea of the topic of the literature review:

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern. This provides the reader with context for reviewing the literature.

- Identify related trends in what has already been published about the topic; or conflicts in theory, methodology, evidence, and conclusions; or gaps in research and scholarship; or a single problem or new perspective of immediate interest.

- Establish your reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature; explain the criteria to be used in analyzing and comparing literature and the organization of the review (sequence); and, when necessary, state why certain literature is or is not included (scope) -

Body : The body of a literature review contains your discussion of sources and can be organized in 3 ways-

- Chronological - by publication or by trend

- Thematic - organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time

- Methodical - the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the "methods" of the literature's researcher or writer that you are reviewing

You may also want to include a section on "questions for further research" and discuss what questions the review has sparked about the topic/field or offer suggestions for future studies/examinations that build on your current findings.

Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should:

Conclude your paper by providing your reader with some perspective on the relationship between your literature review's specific topic and how it's related to it's parent discipline, scientific endeavor, or profession.

Bibliography : Since a literature review is composed of pieces of research, it is very important that your correctly cite the literature you are reviewing, both in the reviews body as well as in a bibliography/works cited. To learn more about different citation styles, visit the " Citing Your Sources " tab.

- Writing a Literature Review: Wesleyan University

- Literature Review: Edith Cowan University

- << Previous: Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eastern.edu/literature_reviews

About the Library

- Collection Development

- Circulation Policies

- Mission Statement

- Staff Directory

Using the Library

- A to Z Journal List

- Library Catalog

- Research Guides

Interlibrary Services

- Research Help

Warner Memorial Library

Researching and writing for Economics students

4 literature review and citations/references.

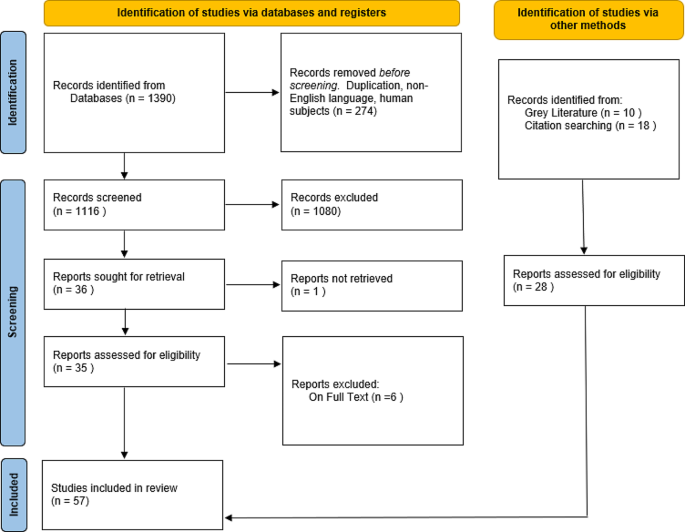

Figure 4.1: Literature reviews and references

Your may have done a literature survey as part of your proposal. This will be incorporated into your dissertation, not left as separate stand-alone. Most economics papers include a literature review section, which may be a separate section, or incorporated into the paper’s introduction. (See organising for a standard format.)

Some disambiguation:

A ‘Literature survey’ paper: Some academic papers are called ‘literature surveys’. These try to summarise and discuss the existing work that has been done on a particular topic, and can be very useful. See, for example, works in The Journal of Economic Perspectives, the Journal of Economic Literature, the “Handbook of [XXX] Economics”

Many student projects and undergraduate dissertations are mainly literature surveys.

4.1 What is the point of a literature survey?

Your literature review should explain:

what has been done already to address your topic and related questions, putting your work in perspective, and

what techniques others have used, what are their strengths and weaknesses, and how might they be relevant tools for your own analysis.

Figure 4.2: Take notes on this as you read, and write them up.

4.2 What previous work is relevant?

Focus on literature that is relevant to your topic only.

But do not focus only on articles about your exact topic ! For example, if your paper is about the relative price of cars in the UK, you might cite papers (i) about the global automobile market, (ii) about the theory and evidence on competition in markets with similar features and (iii) using econometric techniques such as “hedonic regression” to estimate “price premia” in other markets and in other countries.

Consider: If you were Colchester a doctor and wanted to know whether a medicine would be effective for your patients, would you only consider medical studies that ran tests on Colchester residents, or would you consider more general national and international investigations?

4.3 What are “good” economics journal articles?

You should aim to read and cite peer-reviewed articles in reputable economics journals. (Journals in other fields such as Finance, Marketing and Political Science may also be useful.) These papers have a certain credibility as they have been checked by several referees and one or more editors before being published. (In fact, the publication process in Economics is extremely lengthy and difficult.)

Which journals are “reputable”? Economists spend a lot of time thinking about how to rank and compare journals (there are so many papers written about this topic that they someone could start a “Journal of Ranking Economics Journals”. For example, “ REPEC ” has one ranking, and SCIMAGO/SCOPUS has another one. You may want to focus on journals ranked in the top 100 or top 200 of these rankings. If you find it very interesting and relevant paper published somewhere that is ranked below this, is okay to cite it, but you may want to be a bit more skeptical of its findings.

Any journal you find on JSTOR is respectable, and if you look in the back of your textbooks, there will be references to articles in journals, most of which are decent.

You may also find unpublished “working papers”; these may also be useful as references. However, it is more difficult to evaluate the credibility of these, as they have not been through a process of peer review. However, if the author has published well and has a good reputation, it might be more likely that these are worth reading and citing.

Unpublished “working papers”

You may also find unpublished “working papers” or ‘mimeos’; these may also be useful as references. In fact, the publication process in Economics is so slow (six years from first working paper to publication is not uncommon) that not consulting working papers often means not being current.

However, it is more difficult to evaluate the credibility of this ‘grey literature’, as they have not been through a process of peer review. However, if the author has published well and has a good reputation, it might be more likely that these are worth reading and citing. Some working paper series are vetted, such as NBER; in terms of credibility, these might be seen as something in between a working paper and a publication.

Which of the following are “peer-reviewed articles in reputable economics journals”? Which of the following may be appropriate to cite in your literature review and in your final project? 8

Klein, G, J. (2011) “Cartel Destabilization and Leniency Programs – Empirical Evidence.” ZEW - Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. 10-107

Spencer, B. and Brander, J.A. (1983) “International R&D Rivalry and Industrial Strategy”, Review of Economic Studies Vol. 50, 707-722

Troisi, Jordan D., Andrew N. Christopher, and Pam Marek. “Materialism and money spending disposition as predictors of economic and personality variables.” North American Journal of Psychology 8.3 (2006): 421.

The Economist,. ‘Good, Bad And Ugly’. Web. 11 Apr. 2015. [accessed on…]

Mecaj, Arjola, and María Isabel González Bravo. “CSR Actions and Financial Distress: Do Firms Change Their CSR Behavior When Signals of Financial Distress Are Identified?.” Modern Economy 2014 (2014).

Universities, U. K. “Creating Prosperity: the role of higher education in driving the UK’s creative economy.” London Universities UK (2010).

4.4 How to find and access articles

You should be able to find and access all the relevant articles online. Leafing through bound volumes and photocopying should not be neededs. (Having been a student in the late 90’s and 2000’s, I wish I could get those hours back.)

Figure 4.3: The old way!

Good online tools include Jstor (jstor.org) and Google Scholar (scholar.google.co.uk). Your university should have access to Jstor, and Google is accessible to all (although the linked articles may require special access). You will usually have the ‘most access’ when logged into your university or library computing system.If you cannot access a paper, you may want to consult a reference librarian.

It is also ok, if you cannot access the journal article itself, to use the last working paper version (on Google scholar find this in the tab that says “all X versions”, where X is some number, and look for a PDF). However, authors do not always put up the most polished versions, although they should do to promote open-access. As a very last resort, you can e-mail the author and ask him or her to send you the paper.

When looking for references, try to find ones published in respected refereed economics journals (see above ).

4.5 Good starting points: Survey article, course notes, and textbooks

A “survey article” is a good place to start; this is a paper that is largely a categorization and discussion of previous work on a particular topic. You can often find such papers in journals such as

- the Journal of Economic Perspectives,

- the Journal of Economic Surveys,

- and the Journal of Economic Literature.

These will be useful as a “catalog” of papers to read and considers citing. They are also typically very readable and offer a decent introduction to the issue or the field.

It is also helpful to consult module (course) notes and syllabi from the relevant field. Do not only limit yourself to the ones at your own university; many of universities make their course materials publicly accessible online. These will not only typically contain reading lists with well-respected and useful references, they may also contain slides and other material that will help you better understand your topic and the relevant issues.

However, be careful not to take material from course notes without properly citing it. (Better yet, try to find the original paper that the course notes are referring to.)

Textbooks serve as another extremely useful jumping off point. Look through your own textbooks and other textbooks in the right fields. Textbooks draw from, and cite a range of relevant articles and papers. (You may also want to go back to textbooks when you are finding the articles you are reading too difficult. Textbooks may present a simpler version of the material presented in an article, and explain the concepts better.)

4.6 Backwards and forwards with references

When you find a useful paper, look for its “family.” You may want to go back to earlier, more fundamental references, by looking at the articles that this paper cited. See what is listed as “keywords” (these are usually given at the top of the paper), and “JEL codes”. Check what papers this paper cites, and check what other papers cited this paper. On Google scholar you can follow this with a link “Cited by…” below the listed article. “Related articles” is also a useful link.

4.7 Citations

Keep track of all references and citations

You may find it helpful to use software to help you manage your citations

A storage “database” of citations (e.g., Jabref, Zotero, Endnote, Mendeley); these interface well with Google Scholar and Jstor

An automatic “insert citation” and “insert bibliography” in your word processing software

Use a tool like Endnote to manage and insert the bibliographies, or use a bibliography manager software such as Zotero or Jabref,

Further discussion: Citation management tools

List of works cited

Put your list of references in alphabetical order by author’s last name (surname).

Include all articles and works that you cite in your paper; do not include any that you don’t cite.

Avoiding plagiarism and academic offenses**

Here is a definition of plagiarism

The main point is that you need to cite everything that is not your own work. Furthermore, be clear to distinguish what is your own work and your own language and what is from somewhere/someone else.

Why cite? Not just to give credit to others but to make it clear that the remaining uncited content is your own.

Here are some basic rules:

(Rephrased from University of Essex material, as seen in Department of Economics, EC100 Economics for Business Handbook 2017-18, https://www1.essex.ac.uk/economics/documents/EC100-Booklet_2017.pdf accessed on 20 July 2019, pp. 15-16)

Do not submit anything that is not your own work.

Never copy from friends.

Do not copy your own work or previously submitted work. (Caveat: If you are submitting a draft or a ‘literature review and project plan’ at an earlier stage, this can be incorporated into your final submission.

Don’t copy text directly into your work, unless:

- you put all passages in quotation marks: beginning with ’ and ending with ’, or clearly offset from the main text

- you cite the source of this text.

It is not sufficient merely to add a citation for the source of copied material following the copied material (typically the end of a paragraph). You must include the copied material in quotation marks. … Ignorance … is no defence.’ (ibid, pp. 15 )

(‘Ibid’ means ‘same as the previous citation’.)

Your university may use sophisticated plagiarism-detection software. Markers may also report if the paper looks suspect

Before final submission, they may ask you to go over your draft and sign that you understand the contents and you have demonstrated that the work is your own.

Not being in touch with your supervisor may put you under suspicion.

Your university may give a Viva Voce oral exam if your work is under suspicion. It is a cool-sounding word but probably something you want to avoid.

Your university may store your work in its our database, and can pursue disciplinary action, even after you have graduated.

Penalties may be severe, including failure with no opportunity to retake the module (course). You may even risk your degree!

Comprehension questions; answers in footnotes

True or false: “If you do not directly quote a paper you do not need to cite it” 9

You should read and cite a paper (choose all that are correct)… 10

- If it motivates ‘why your question is interesting’ and how it can be modeled economically

- Only if it asks the same question as your paper

- Only if it is dealing with the same country/industry/etc as you are addressing

- If it has any connection to your topic, question, or related matters

- If it answers a similar question as your paper

- If it uses and discusses techniques that inform those you are using

4.8 How to write about previous authors’ analysis and findings

Use the right terminology.

“Johnson et al. (2000) provide an analytical framework that sheds substantial doubt on that belief. When trying to obtain a correlation between institutional efficiency and wealth per capita, they are left with largely inconclusive results.”

They are not trying to “obtain a correlation”; they are trying to measure the relationship and test hypotheses.

“Findings”: Critically examine sources

Don’t take everything that is in print (or written online) as gospel truth. Be skeptical and carefully evaluate the arguments and evidence presented. Try to really survey what has been written, to consider the range of opinions and the preponderance of the evidence. You also need to be careful to distinguish between “real research” and propaganda or press releases.

The returns to higher education in Atlantis are extremely high. For the majority of Atlanian students a university degree has increased their lifetime income by over 50%, as reported in the “Benefits of Higher Education” report put out by the Association of Atlantian Universities (2016).

But don’t be harsh without explanation:

Smith (2014) found a return to education in Atlantis exceeding 50%. This result is unlikely to be true because the study was not a very good one.

“Findings:” “They Proved”

A theoretical economic model can not really prove anything about the real world; they typically rely on strong simplifying assumptions.

Through their economic model, they prove that as long as elites have incentives to invest in de facto power, through lobbying or corruption for example, they will invest as much as possible in order to gain favourable conditions in the future for their businesses.

In their two period model, which assumes \[details of key assumptions here\] , they find that when an elite Agent has an incentive to invest in de facto power, he invests a strictly positive amount, up to the point where marginal benefit equals marginal cost”

Empirical work does not “prove” anything (nor does it claim to).

It relies on statistical inference under specific assumptions, and an intuitive sense that evidence from one situation is likely to apply to other situations.

“As Smith et al (1999) proved using data from the 1910-1920 Scandanavian stock exchange, equity prices always increase in response to reductions in corporate tax rates.”

“Smith et al (199) estimated a VAR regression for a dynamic CAP model using data from the 1910-1920 Scandanavian stock exchange. They found a strongly statistically significant negative coefficient on corporate tax rates. This suggests that such taxes may have a negative effect on publicly traded securities. However, as their data was from a limited period with several simultaneous changes in policy, and their results are not robust to \[something here\] , further evidence is needed on this question.”

Use the language of classical 11 statistics:

Hypothesis testing, statistical significance, robustness checks, magnitudes of effects, confidence intervals.

Note that generalisation outside the data depends on an intuitive sense that evidence from one situation is likely to apply to other situations.

“Findings”: How do you (or the cited paper) claim to identify a causal relationship?

This policy was explained by Smith and Johnson (2002) in their research on subsidies and redistribution in higher education. Their results showed that people with higher degree have higher salaries and so pay higher taxes. Thus subsidizing higher education leads to a large social gain.

The results the student discusses seem to show an association between higher degrees and higher salaries. The student seems to imply that the education itself led to higher salaries. This has not been shown by the cited paper. Perhaps people who were able to get into higher education would earn higher salaries anyway. There are ways economists used to try to identify a “causal effect” (by the way, this widely used term is redundant as all effects must have a cause), but a mere association between two variables is not enough

As inflation was systematically lower during periods of recession, we see that too low a level of inflation increases unemployment.