More From Forbes

Why do college professors need doctorate degrees.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Shutterstock

Why is a PhD required to be a professor at almost every university? originally appeared on Quora : the place to gain and share knowledge, empowering people to learn from others and better understand the world .

Answer by Ben Waggoner , PhD, biology professor, on Quora :

Back about 700 years ago, if you wanted to become, say, a sculptor, you signed on as an apprentice to a master sculptor. At first, you’d do all the menial jobs; sweeping and mopping the floor, hauling the blocks of stone, sharpening the tools, making the coffee (OK, maybe not in the actual Middle Ages as such)... and when he felt like it, your master would show you the basics of carving stone. You'd start getting some practice under the master’s supervision, maybe carving some waste bits of stone that the master didn’t need. If you aren't too bad at it, you might go on to do parts of a sculpture yourself—maybe the parts that few people will see, like the rear end of an angel statue that will end up fifty feet up a wall, or something. As you get more practice, you are trusted with more and more complex tasks, you get more and more experience, you learn more and more of what the master can teach you and eventually, you get the chance to carve a statue all by yourself. It gets judged by the local guild of stone carvers and if it’s good enough, you become a master stone carver yourself. That statue becomes your “master piece”—in fact, that’s what the word originally meant: a piece of work that showed that you could work on the level of a master.

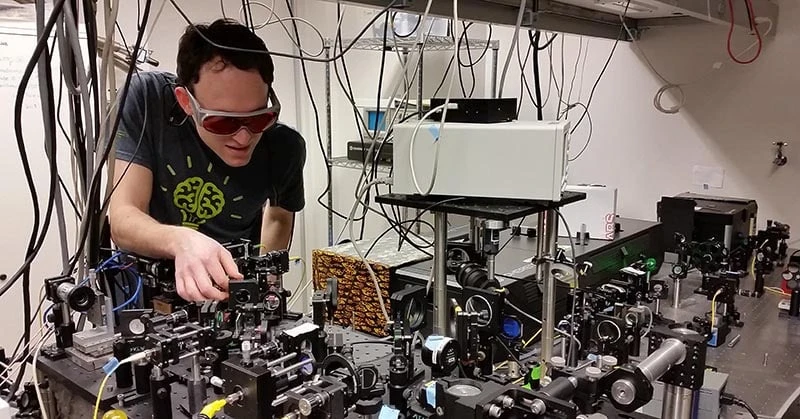

This is what a PhD basically is. Exactly how it works can vary from department to department, and from university to university, but basically, you stop taking the kinds of classes that you took as an undergraduate (unless you need a few to fill in gaps in your background knowledge, or to pick up skills that will be useful). Most of your classes are seminars and discussions. But most of your time and effort goes into creating what is, hopefully, an original piece of research. With guidance from your major professor (which can range from helicoptering to malignant neglect, but hopefully is a happy medium between the two extremes), and hopefully some funding and resources through your major professor as well, you come up with an unsolved problem in your field, or a question that hasn’t been addressed before, and you answer it. In the sciences, you design the experiments or field studies and then go out and try to do them; in the liberal arts, you design whatever program of reading and research you need. And if all goes well you bring it to a successful conclusion, publish your results for the academic community to see, and receive your PhD.

What the PhD shows is not so much that you know a lot of stuff that you can repeat. It shows that you know how to add to humanity’s store of knowledge. It shows that you can follow the standards of your academic field and produce something that nobody thought of before. It shows that you know how new knowledge is arrived at. And hopefully, you’ll be able to keep on doing that for the rest of your career, adding to the sum of our knowledge, and knowing how to add to it in a valid way.

That’s why a PhD is required, at least for tenure-track employment, at most universities in most departments. Being a professor means not just that you repeat memorized facts to anyone who doesn’t run away fast enough. You’re expected to do research, or other scholarship, that advances the state of knowledge in your field—just as our medieval sculptor was expected to produce new sculptures and statues, not just copies of older ones.

(Note: In some fields, like creative writing and studio art, the Master of Fine Arts or MFA degree is usually the highest degree a professor has—this is normal. The idea is still the same: to get the MFA, you have to write and publish creative writings, create a sizable portfolio of art and show it in galleries, etc. At some universities, people may be hired without PhDs because there may be other considerations: at the Baptist college in my town, at least as of a few years ago, you had to be a Baptist of a particular sect in order to be hired as a professor, and the science department mostly consisted of people who hadn’t finished their PhD—but who were staunch Baptists of the correct variety. And at my university, we do have people on the faculty who have Master’s degrees but not the PhD—however, they teach lower-division courses, they’re not expected to do research, they don’t get paid as much, and while some have pretty stable positions, others might teach for a couple of years and then go on to do something else.)

This question originally appeared on Quora - the place to gain and share knowledge, empowering people to learn from others and better understand the world. You can follow Quora on Twitter , Facebook , and Google+ . More questions:

- Doctor of Philosophy Degrees : Why did you do a PhD if you didn't want to go into academia?

- Colleges and Universities : Does attending an Ivy League school really matter?

- Academia : What is it like to be a professor?

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

The 19 Steps to Becoming a College Professor

Other High School , College Info

Do you love conducting research and engaging with students? Can you envision yourself working in academia? Then you're probably interested in learning how to become a college professor. What are the basic requirements for becoming a college professor? What specific steps should you take in order to become one?

In this guide, we start with an overview of professors, taking a close look at their salary potential and employment growth rate. We then go over the basic college professor requirements before giving you a step-by-step guide on how to become one.

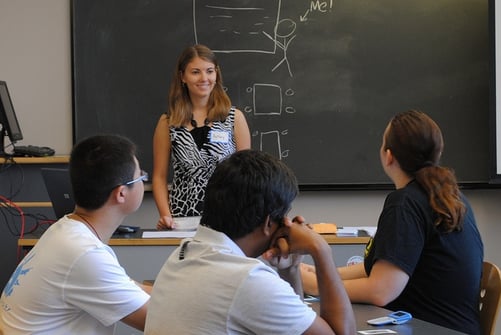

Feature Image: Georgia Southern /Flickr

Becoming a College Professor: Salary and Job Outlook

Before we dive into our discussion of salaries and employment growth rates, it's important to be aware of the incredible challenge of becoming a college professor.

These days, it is unfortunately well known that the number of people qualified to be professors far outnumbers the availability of professor job openings , which means that the job market is extremely competitive. Even if you do all the steps below, the chances of your actually becoming a college professor are slim —regardless of whether you want to teach in the humanities or sciences .

Now that we've gone over the current status of the professor job market, let's take a look at some hard figures for salary and employment growth rate.

Salary Potential for Professors

First, what is the salary potential for college professors? The answer to this question depends a lot on what type of professor you want to be and what school you end up working at .

In general, though, here's what you can expect to make as a professor. According to a recent study conducted by the American Association of University Professors , the average salaries for college professors are as follows :

- Full professors: $140,543

- Associate professors: $95,828

- Assistant professors: $83,362

- Part-time faculty members: $3,556 per standard course section

As you can see, there's a pretty huge range in professors' salaries , with full professors typically making $40,000-$50,000 more per year than what associate and assistant professors make.

For adjunct professors (i.e., part-time teachers), pay is especially dismal . Many adjunct professors have to supplement their incomes with other jobs or even public assistance, such as Medicaid, just to make ends meet.

One study notes that adjuncts make less than minimum wage when taking into account non-classroom work, including holding office hours and grading papers.

All in all, while it's possible to make a six-figure salary as a college professor, this is rare, especially considering that 73% of college professors are off the tenure track .

Employment Rates for Professors

Now, what about employment rates for professor jobs? According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the projected growth rate for postsecondary teachers in the years 2020-2030 is 12% —that's 4% higher than the average rate of growth of 8%.

That said, most of this employment growth will be in part-time (adjunct) positions and not full-time ones. This means that most professor job openings will be those with the lowest salaries and lowest job security .

In addition, this job growth will vary a lot by field (i.e., what you teach). The chart below shows the median salaries and projected growth rates for a variety of fields for college professors (arranged alphabetically):

| $90,340 | 2% | |

| $89,220 | 4% | |

| $90,880 | 5% | |

| $78,840 | 5% | |

| $69,690 | 6% | |

| $94,520 | 2% | |

| $85,600 | 9% | |

| $88,010 | 12% | |

| $80,400 | 4% | |

| $71,030 | 3% | |

| $85,540 | 3% | |

| $63,560 | 7% | |

| $107,260 | 5% | |

| $65,440 | 5% | |

| $103,600 | 9% | |

| $69,000 | 2% | |

| $84,740 | 4% | |

| $69,990 | 6% | |

| $87,400 | 2% | |

| $82,330 | 3% | |

| $99,090 | 21% | |

| $76,890 | 4% | |

| $116,430 | 7% | |

| $71,580 | 3% | |

| $73,650 | 1% | |

| $75,470 | 18% | |

| $76,160 | 7% | |

| $90,400 | 4% | |

| $85,760 | 5% | |

| $78,180 | 9% | |

| $69,340 | 0% | |

| $71,570 | 6% | |

| $75,610 | 4% |

Source: BLS.gov

As this chart indicates, depending on the field you want to teach in, your projected employment growth rate could range from 0% to as high as 21% .

The fastest growing college professor field is health; by contrast, the slowest growing fields are social sciences, mathematical science, atmospheric and earth sciences, computer science, and English language and literature. All of these are growing at a slower-than-average pace (less than 5%).

Law professors have the highest salary , with a median income of $116,430. On the opposite end, the lowest-earning field is criminal justice and law enforcement, whose professors make a median salary of $63,560—that's over $50,000 less than what law professors make.

College Professor Requirements and Basic Qualifications

In order to become a college professor, you'll need to have some basic qualifications. These can vary slightly among schools and fields, but generally you should expect to need the following qualifications before you can become a college professor .

#1: Doctoral Degree in the Field You Want to Teach In

Most teaching positions at four-year colleges and universities require applicants to have a doctoral degree in the field they wish to teach in.

For example, if you're interested in teaching economics, you'd likely need to get a PhD in economics. Or if you're hoping to teach Japanese literature, you'd get a PhD in a relevant field, such as Japanese studies, Japanese literature, or comparative literature.

Doctoral programs usually take five to seven years and require you to have a bachelor's degree and a master's degree. (Note, however, that many doctoral programs do allow you to earn your master's along the way.)

But is it possible to teach college-level classes without a doctoral degree? Yes—but only at certain schools and in certain fields.

As the BLS notes, some community colleges and technical schools allow people with just a master's degree to teach classes ; however, these positions can be quite competitive, so if you've only got a master's degree and are up against applicants with doctorates, you'll likely have a lower chance of standing out and getting that job offer .

In addition, some fields let those with just master's degrees teach classes. For example, for creative writing programs, you'd only need a Master of Fine Arts.

#2: Teaching Experience

Another huge plus for those looking to become professors is teaching experience. This means any experience with leading or instructing classes or students.

Most college professors gain teaching experience as graduate students. In many master's and doctoral programs, students are encouraged (sometimes even required) to either lead or assist with undergraduate classes.

At some colleges, such as the University of Michigan, graduate students can get part-time teaching jobs as Graduate Student Instructors (GSIs) . For this position, you'll usually teach undergraduate classes under the supervision of a full-time faculty member.

Another college-level teaching job is the Teaching Assistant or Teacher's Aide (TA) . TAs assist the main professor (a full-time faculty member) with various tasks, such as grading papers, preparing materials and assignments, and leading smaller discussion-based classes.

#3: Professional Certification (Depending on Field)

Depending on the field you want to teach in, you might have to obtain certification in something in addition to getting a doctoral degree. Here's what the BLS says about this:

"Postsecondary teachers who prepare students for an occupation that requires a license, certification, or registration, may need to have—or they may benefit from having—the same credential. For example, a postsecondary nursing teacher might need a nursing license or a postsecondary education teacher might need a teaching license."

Generally speaking, you'll only need certification or a license of some sort if you're preparing to teach in a technical or vocational field , such as health, education, or accounting.

Moreover, while you don't usually need any teaching certification to be able to teach at the college level, you will need it if you want to teach at the secondary level (i.e., middle school or high school).

#4: Publications and Prominent Academic Presence

A high number of publications is vital to landing a job as a professor. Since full-time college-level teaching jobs are extremely competitive, it's strongly encouraged (read: basically required!) that prospective professors have as many academic publications as possible .

This is particularly important if you're hoping to secure a tenure-track position, which by far offers the best job security for professors. Indeed, the famous saying " publish or perish " clearly applies to both prospective professors and practicing professors.

And it's not simply that you'll need a few scholarly articles under your belt— you'll also need to have big, well-received publications , such as books, if you want to be a competitive candidate for tenure-track teaching positions.

Here's what STEM professor Kirstie Ramsey has to say about the importance of publications and research when applying for tenure-track jobs:

"Many colleges and universities are going through a transition from a time when research was not that important to a time when it is imperative. If you are at one of these institutions and you were under the impression that a certain amount of research would get you tenure, you should not be surprised if the amount of research you will need increases dramatically before you actually go up for tenure. At first I thought that a couple of peer-reviewed articles would be enough for tenure, especially since I do not teach at a research university and I am in a discipline where many people do not go into academe. However, during my first year on the tenure track at my current institution, I realized that only two articles would not allow me to jump through the tenure hoop."

To sum up, it's not just a doctorate and teaching experience that make a professor, but also lots and lots of high-quality, groundbreaking research .

How to Become a Professor: 19-Step Guide

Now that we've gone over the basic college professor requirements, what specific steps should you take to become one? What do you need to do in high school? In college? In graduate school?

Here, we introduce to you our step-by-step guide on how to become a college professor . We've divided the 19 steps into four parts:

- High School

- Graduate School (Master's Degree)

- Graduate School (Doctorate)

Part 1: High School

It might sound strange to start your path to becoming a professor in high school, but doing so will make the entire process go a lot more smoothly for you. Here are the most important preliminary steps you can take while still in high school.

- Step 1: Keep Up Your Grades

Although all high school students should aim for strong GPAs , because you're specifically going into the field of education, you'll need to make sure you're giving a little extra attention to your grades . Doing this proves that you're serious about not only your future but also education as a whole—the very field you'll be entering!

Furthermore, maintaining good grades is important for getting into a good college . Attending a good college could, in turn, help you get into a more prestigious graduate school and obtain a higher-paying teaching job .

If you already have an idea of what subject you'd like to teach, try to take as many classes in your field as possible . For example, if you're a lover of English, you might want to take a few electives in subjects such as journalism or creative writing. Or if you're a science whiz, see whether you can take extra science classes (beyond the required ones) in topics such as marine science, astronomy, or geology.

Again, be sure that you're getting high marks in your classes , particularly in the ones that are most relevant to the field you want to teach in.

- Step 2: Tutor in Your Spare Time

One easy way of gaining teaching experience as a high school student is to become a tutor. Pick a subject you're strong at—ideally, one you might want to eventually teach—and consider offering after-school or weekend tutoring services to your peers or other students in lower grades.

Tutoring will not only help you decide whether teaching is a viable career path for you, but it'll also look great on your college applications as an extracurricular activity .

- Step 3: Get a High SAT/ACT Score

Since you'll need to go to graduate school to become a professor, it'll be helpful if you can get into a great college. To do this, you'll need to have an impressive SAT/ACT score .

Ideally, you'll take your first SAT or ACT around the beginning of your junior year. This should give you enough time to take the test again in the spring, and possibly a third time during the summer before or the autumn of your senior year.

The SAT/ACT score you'll want to aim for depends heavily on which colleges you apply to.

For more tips on how to set a goal score, check out our guides to what a great SAT / ACT score is .

- Step 4: Submit Impressive College Applications

Though it's great to attend a good college, where you go doesn't actually matter too much—just as long as it offers an academic program in the (broad) field or topic you're thinking of teaching in.

To get into the college of your choice, however, you'll still want to focus on putting together a great application , which will generally include the following:

- A high GPA and evidence of rigorous coursework

- Impressive SAT/ACT scores

- An effective personal statement/essay

- Strong letters of recommendation (if required)

Be sure to give yourself plenty of time to work on your applications so you can submit the best possible versions of them before your schools' deadlines .

If you're aiming for the Ivy League or other similarly selective institutions, check out our expert guide on how to get into Harvard , written by a real Harvard alum.

Part 2: College

Once you get into college, what can you do to help your chances of getting into a good grad school and becoming a college professor? Here are the next steps to take.

- Step 5: Declare a Major in the Field You Want to Teach

Perhaps the most critical step is to determine what exactly you want to teach in the future—and then major in it (or a related field) . For instance, if after taking some classes in computer science you decide that you really want to teach this subject, then go ahead and declare it as your major.

If you're still not sure what field you'll want to teach in, you can always change your major later on or first declare your field of interest as a minor (and then change it to a major if you wish). If the field you want to teach is not offered as a major or minor at your college, try to take as many relevant classes as possible.

Although it's not always required for graduate school applicants to have majored in the field they wish to study at the master's or doctoral level, it's a strong plus in that it shows you've had ample experience with the subject and will be able to perform at a high level right off the bat.

- Step 6: Observe Your Professors in Action

Since you're thinking of becoming a college professor, this is a great time to sit down and observe your professors to help you determine whether teaching at the postsecondary level is something you're truly interested in pursuing.

In your classes, evaluate how your professors lecture and interact with students . What kinds of tools, worksheets, books, and/or technology do they use to effectively engage students? What sort of atmosphere do they create for the class?

It's also a good idea to look up your professors' experiences and backgrounds in their fields . What kinds of publications do they have to their name? Where did they get their master's and doctoral degrees? Are they tenured or not? How long have they been teaching?

If possible, I recommend meeting with a professor directly (ideally, one who's in the same field you want to teach in) to discuss a career in academia. Most professors will be happy to meet with you during their office hours to talk about your career interests and offer advice.

Doing all of this will give you an inside look at what the job of professor actually entails and help you decide whether it's something you're passionate about.

- Step 7: Maintain Good Grades

Because you'll need to attend graduate school after college, it's important to maintain good grades as an undergraduate, especially in the field you wish to teach. This is necessary because most graduate programs require a minimum 3.0 undergraduate GPA for admission .

Getting good grades also ensures that you'll have a more competitive application for grad school, and indicates that you take your education seriously and are passionate about learning.

- Step 8: Get to Know Your Professors

Aside from watching how your professors teach, it's imperative to form strong relationships with them outside of class , particularly with those who teach in the field you want to teach as well.

Meet with professors during their office hours often. Consult them whenever you have questions about assignments, papers, projects, or your overall progress. Most importantly, don't be afraid to talk to them about your future goals!

You want to build a strong rapport with your professors, which is basically the same thing as networking. This way, you'll not only get a clearer idea of what a professor does, but you'll also guarantee yourself stronger, more cogent letters of recommendation for graduate school .

- Step 9: Gain Research and/or Publication Experience

This isn't an absolute necessity for undergraduates, but it can certainly be helpful for your future.

If possible, try to gain research experience through your classes or extracurricular projects . For instance, you could volunteer to assist a professor with research after class or get a part-time job or internship as a research assistant.

If neither option works, consider submitting a senior thesis that involves a heavy amount of research . Best case scenario, all of your research will amount to a publication (or two!) with your name on it.

That being said, don't fret too much about getting something published as an undergraduate . Most students don't publish anything in college yet many go on to graduate school, some of whom become college professors. Rather, just look at this as a time to get used to the idea of researching and writing about the results of your research.

- Step 10: Take the GRE and Apply to Grad School

If you're hoping to attend graduate school immediately after college, you'll need to start working on your application by the fall of your senior year .

One big part of your graduate school application will be GRE scores , which are required for many graduate programs. The GRE is an expensive test , so it's best if you can get away with taking it just once (though there's no harm in taking it twice).

Although the GRE isn't necessarily the most important feature of your grad school application , you want to make sure you're dedicating enough time to it so that it's clear you're really ready for grad school.

Other parts of your grad school application will likely include the following:

- Undergraduate transcripts

- Personal statement / statement of purpose

- Curriculum vitae (CV) / resume

- Letters of recommendation

For more tips on the GRE and applying to grad school, check out our GRE blog .

Part 3: Graduate School (Master's Degree)

Once you've finished college, it's time to start thinking about graduate school. I'm breaking this part into two sections: master's degree and doctorate .

Note that although some doctoral programs offer a master's degree along the way, others don't or prefer applicants who already have a master's degree in the field.

- Step 11: Continue to Keep Up Your Grades

Again, one of your highest priorities should be to keep up your grades so you can get into a great doctoral program once you finish your master's program. Even more important, many graduate programs require students to get at least Bs in all their classes , or else they might get kicked out of the program! So definitely focus on your grades.

- Step 12: Become a TA

One great way to utilize your graduate program (besides taking classes!) is to become a Teaching Assistant, or TA, for an undergraduate class. As a TA, you will not only receive a wage but will also gain lots of firsthand experience as a teacher at the postsecondary level .

Many TAs lead small discussion sections or labs entirely on their own, offering a convenient way to ease into college-level teaching.

TAs' duties typically involve some or all of the following:

- Grading papers and assignments

- Leading small discussion or lab sections of a class (instead of its large lecture section)

- Performing administrative tasks for the professor

- Holding office hours for students

The only big negative with being a TA is the time commitment ; therefore, be sure you're ready and willing to dedicate yourself to this job without sacrificing your grades and academic pursuits.

- Step 13: Research Over the Summer

Master's programs in the US typically last around two years, giving you at least one summer during your program. As a result, I strongly recommend using this summer to conduct some research for your master's thesis . This way you can get a head start on your thesis and won't have to cram in all your research while also taking classes.

What's more, using this time to research will give you a brief taste of what your summers might look like as a professor , as college professors are often expected to perform research over their summer breaks .

Many graduate programs offer summer fellowships to graduate students who are hoping to study or conduct research (in or outside the US). My advice? Apply for as many fellowships as possible so you can give yourself the best chance of getting enough money to support your academic plans.

- Step 14: Write a Master's Thesis

Even if your program doesn't require a thesis, you'll definitely want to write one so you can have proof that you're experienced with high-level research . This type of research could help your chances of getting into a doctoral program by emphasizing your commitment to the field you're studying. It will also provide you with tools and experiences that are necessary for doing well in a doctoral program and eventually writing a dissertation.

Step 15: Apply to Doctoral Programs OR Apply for Teaching Jobs

This step has two options depending on which path you'd rather take.

If you really want to teach at a four-year college or university, then you must continue on toward a doctorate . The application requirements for doctoral programs are similar to those for master's programs . Read our guide for more information about grad school application requirements .

On the other hand, if you've decided that you don't want to get a doctorate and would be happy to teach classes at a community college or technical school, it's time to apply for teaching jobs .

To start your job hunt, meet with some of your current or past professors who teach in the field in which you'll also be teaching and see whether they know of any job openings at nearby community colleges or technical schools. You might also be able to use some professors as references for your job applications (just be sure to ask them before you write down their names!).

If you can't meet with your professors or would rather look for jobs on your own, try browsing the career pages on college websites or looking up teaching jobs on the search engine HigherEdJobs .

Part 4: Graduate School (Doctorate)

The final part of the process (for becoming a college professor at a four-year institution) is to get your doctoral degree in the field you wish to teach . Here's what you'll need to do during your doctoral program to ensure you have the best chance of becoming a college professor once you graduate.

- Step 16: Build Strong Relationships With Professors

This is the time to really focus on building strong relationships with professors—not just with those whose classes you've taken but also with those who visit the campus to give talks, hold seminars, attend conferences, etc. This will give you a wider network of people you know who work in academia, which will (hopefully) make it a little easier for you to later land a job as a professor.

Make sure to maintain a particularly strong relationship with your doctoral advisor . After all, this is the professor with whom you'll work the most closely during your time as a doctoral student and candidate. Be open with your advisor : ask her for advice, meet with her often, and check that you're making satisfactory progress toward both your doctorate and your career goals.

- Step 17: Work On Getting Your Research Published

This is also the time to start getting serious about publishing your research.

Remember, it's a huge challenge to find a job as a full-time professor , especially if all you have is a PhD but no major publications. So be sure to focus on not only producing a great dissertation but also contributing to essays and other research projects .

As an article in The Conversation notes,

"By far the best predictor of long-term publication success is your early publication record—in other words, the number of papers you've published by the time you receive your PhD. It really is first in, best dressed: those students who start publishing sooner usually have more papers by the time they finish their PhD than do those who start publishing later."

I suggest asking your advisor for advice on how to work on getting some of your research published if you're not sure where to start.

- Step 18: Write a Groundbreaking Dissertation

You'll spend most of your doctoral program working on your dissertation—the culmination of your research. In order to eventually stand out from other job applicants, it's critical to come up with a highly unique dissertation . Doing this indicates that you're driven to conduct innovative research and make new discoveries in your field of focus.

You might also consider eventually expanding your dissertation into a full-length book .

- Step 19: Apply for Postdoc/Teaching Positions

Once you've obtained your doctorate, it's time to start applying for college-level teaching jobs!

One option you have is to apply for postdoctoral (postdoc) positions . A postdoc is someone who has a doctorate and who temporarily engages in "mentored scholarship and/or scholarly training." Postdocs are employed on a short-term basis at a college or university to help them gain further research and teaching experience.

While you can theoretically skip the postdoc position and dive straight into applying for long-term teaching jobs, many professors have found that their postdoc work helped them build up their resumes/CVs before they went on to apply for full teaching positions at colleges .

In an article for The Muse , Assistant Professor Johanna Greeson at Penn writes the following about her postdoc experience:

"Although I didn't want to do a post-doc, it bought me some time and allowed me to further build my CV and professional identity. I went on the market a second time following the first year of my two-year post-doc and was then in an even stronger position than the first time."

Once you've completed your postdoc position, you can start applying for full-time faculty jobs at colleges and universities. And what's great is that you'll likely have a far stronger CV/resume than you had right out of your doctoral program .

Conclusion: How to Become a College Professor

Becoming a college professor takes years of hard work, but it's certainly doable as long as you know what you'll need to do in order to prepare for the position and increase your chances of securing a job as a professor.

Overall, it's extremely difficult to become a professor. Nowadays, there are many more qualified applicants than there are full-time, college-level teaching positions , making tenure-track jobs in particular highly competitive.

Although the employment growth rate for professors is a high 11%, this doesn't mean that it'll be easy to land a job as a professor . Additionally, salaries for professors can vary a lot depending on the field you teach in and the institution you work at; you could make as little as minimum wage (as an adjunct/part-time professor) or as much as $100,000 or higher (as a full professor).

For those interested in becoming a professor, the basic college professor requirements are as follows :

- A doctoral degree in the field you want to teach in

- Teaching experience

- Professional certification (depending on your field)

- Publications and prominent academic presence

In terms of the steps needed for becoming a college professor, I will list those again briefly here. Feel free to click on any steps you'd like to reread!

- Step 15: Apply to Doctoral Programs or Apply for Teaching Jobs

Good luck with your future teaching career!

What's Next?

Considering other career paths besides teaching? Then check out our in-depth guides to how to become a doctor and how to become a lawyer .

No matter what job (or jobs!) you end up choosing, you'll likely need a bachelor's degree—ideally, one from a great school. Get tips on how to submit a memorable college application , and learn how to get into Harvard and other Ivy League schools with our expert guide.

Need help finding jobs? Take a look at our picks for the best job search websites to get started.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Do You Need a PhD to Be a Professor?

If you want to work in higher education, you may be wondering, “Do you need a PhD to be a professor?”

Professors are experts in their fields who teach courses, conduct research, and support their academic institutions.

Editorial Listing ShortCode:

The type of degree that’s required to work as a professor depends on where you work and what types of courses you want to teach. Learning how to become a college professor is vital if you hope to serve as a faculty member at a college or university.

You don’t necessarily need a PhD to become a professor. Colleges and universities often hire professors with other types of degrees. In that case, what degree do you need to be a professor?

Graduates of master’s programs are often qualified to work as professors, particularly at two-year institutions. These professionals may have more limited responsibilities than professors with PhDs, and they are sometimes limited to teaching introductory courses.

Schools that require professors to hold a doctoral degree may accept another type of professor degree from an accredited university. These are some of the professional doctorate degrees that prospective employers may consider in place of a PhD:

- Doctor of Education

- Doctor of Arts

- Doctor of Business Administration

- Doctor of Public Health

- Doctor of Science

- Doctor of Chemistry

- Doctor of Medicine

Job candidates who don’t hold a PhD may be able to strengthen their candidacy for a position with professional experience. Publishing articles or books that contribute to the field is also beneficial, as it reflects a high level of expertise.

The education requirement for a career as a professor differs between colleges, so it’s essential to review each institution’s policy before applying for a position.

How to Become a Professor

Becoming a professor requires a series of academic and professional steps, including:

- Earning a bachelor’s degree . The pursuit of a professor position begins with a bachelor’s degree. Although it’s helpful to select a field that’s related to your career goal, bachelors programs are an opportunity to explore your interests, and many master’s programs accept students with various degrees.

- Entering graduate school . Some students complete separate master’s and PhD programs. Others enroll in accelerated programs and earn their master’s degree while also working toward their PhD.

- Taking comprehensive exams . Once you have completed your coursework, you will take a series of exams covering the material you studied. The exam may take the form of a written or oral test, portfolio, or research paper.

- Completing a dissertation . Most PhD programs require students to complete a dissertation, an extensive project that may require several years of research and writing. The final stage of a dissertation is typically the oral defense, during which you present your paper and findings to a committee of faculty and answer their questions.

- Gaining experience . It may be beneficial to work as a lecturer or adjunct instructor prior to becoming a professor. This offers evidence of your teaching skills to prospective employers.

- Applying for positions . Even if your doctoral degree is not yet completed, you can begin applying for professor positions while working on your dissertation. The hiring process generally includes submitting an application, a curriculum vitae, and letters of recommendation as well as participating in an interview and presentation or teaching demonstration.

It can be competitive to find a position as a professor, so it may be necessary to apply for positions at multiple schools before finding the right role.

Are All Professors Doctors?

Not all professors are doctors, but many are. Professors are only considered doctors if they hold a doctoral degree, such as a PhD or professional doctorate.

Professors with masters degrees are not classified or addressed as doctors. Because professors need a high level of knowledge and experience in their field, a PhD is a common requirement for this type of position. Many prominent schools only hire graduates of PhD programs for full-time roles as professors.

Is a PhD a Doctor?

A person who holds a PhD is a doctor , but they hold a Doctor of Philosophy rather than a Doctor of Medicine. Medical doctors, or MDs, treat patients, diagnose health conditions, and study diseases, and they complete their degrees at medical schools.

Some PhDs specialize in medicine or health care, but PhDs can also be members of many other fields. For example, a student might obtain a PhD in Sociology, Business Administration, or Higher Education. Online PhD programs are available at a variety of colleges and universities.

What Can You Get a PhD In?

Doctoral degrees are offered in many disciplines, including:

- Sciences . Students can pursue degrees in subjects such as physics, chemistry, and engineering.

- Health care . Physical therapy and audiology are potential areas of study for students hoping to work in health care.

- Education . A PhD in Education may help you advance in your teaching career or become a school administrator.

- Psychology . Programs in psychology are ideal for students who want to work as psychologists or researchers.

- English . Many schools offer English PhDs focused on literature, while others emphasize writing and rhetoric.

When choosing what PhD you can get in , it helps to consider your academic background and interests.

Can You Be a Professor with a Masters?

Yes, you can be a professor with a master’s degree. Many schools hire professionals with master’s degrees to serve as entry-level instructors.

Community colleges and two-year institutions are especially popular employers for graduates of master’s programs. Four year colleges may also hire job candidates with master’s degrees, but they often work as adjuncts rather than as full-time employees. Adjuncts have temporary positions and may not receive benefits.

Because of the high level of competition for academic positions in certain disciplines, it may be easier to get a job as a professor with a Ph.D. rather than a master’s degree.

What Does a Professor Do?

Professors have a wide range of responsibilities. Most people in this role are responsible for teaching several courses within their discipline. They may also develop or update curriculum and assessments for their departments.

In addition to teaching, professors usually offer advising to students and supervise their graduate research projects, such as dissertations. They often join college committees that focus on improving practices and policies within the institution.

Many professors also conduct original research and write journal articles for publication. These contributions are often a requirement for receiving tenure.

How Much Do College Professors Make?

The salary for a postsecondary teacher can differ based on your location, the specific school where you work, your level of experience, and your discipline or specialization.

For example, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics , the median annual salary for engineering professors is $103,550. This is higher than the median wage for business professors, which is $88,790. Some professors who want to work outside of the classroom become instructional coordinators. Professionals in this area earn median salaries of $66,490 per year.

A career as a professor may eventually lead to a job as a postsecondary education administrator. The median salary for this type of position is $99,940.

What’s the Difference Between an Assistant vs. Associate Professor?

Although they both teach courses at the college level, assistant and associate professors have separate roles with notable differences.

Many professors are initially hired as assistant professors and progress to become associate professors.

Becoming a Professor

Do you need a doctorate to be a professor? The answer to this question changes based on the requirements of each specific academic institution.

No matter where you hope to work, certain steps are necessary before you can work as a professor. The path generally begins with a bachelor’s degree and culminates with a master’s degree or a doctoral degree, such as a PhD.

Whether you’re considering different bachelors degrees or are ready to enroll in a PhD program, you can begin your journey toward becoming a professor by researching accredited colleges and universities.

Do You Need a PhD to Be a Professor?

Colleges and universities assign faculty members different academic ranks that signify how much training and experience they have. These ranks indicate the level of education and other requirements necessary to obtain that position, according to Bradley University. Full-time academic ranks include assistant, associate and full professor.

Advertisement

Though non-doctoral teachers can secure jobs in higher education, in order to secure the title of professor, they must have a terminal degree in their field. Earning the Ph.D. -- the terminal degree in any field -- gives professors the academic knowledge and expertise to teach at the post-secondary level. In addition to having a Ph.D., you'll also need to have teaching experience and get published to prove that you know your field inside and out.

Video of the Day

Schools seek Ph.D.s to teach their students not only to provide the highest-quality education possible, but also to increase a department's or college's reputation. Also, the higher your degree, the higher your pay , even if you teach the same class as someone with a lower degree.

Assistant Professor Requirements

As the junior faculty member in an academic department, the assistant professor is almost always a recent doctoral graduate starting his career in higher education. Even though the assistant professor is the lowest ranking for a full-time professor, it still usually requires a Ph.D., with rare exceptions.

Most colleges and universities prefer that the assistant professor has some teaching experience, which he might have garnered as he earned his Ph.D. Assistant professors also need to work on scholarship by presenting their research and engaging in service on campus and beyond.

Associate Professor Requirements

What is associate professor? In order for a person to earn the title of associate professor, she has to meet all of the requirements of an assistant professor, including holding the Ph.D. or terminal degree in her field. She has to demonstrate strong teaching skills as well as scholarly performance outside of the classroom. A promotion to associate professor might require that the person publish several academic journal articles or a book to promote her research. Having the Ph.D. behind her name can make this challenging effort a bit easier.

Full Professor Requirements

Accomplished professors can earn the title of full professor – the highest academic rank – after a proven record of scholarly success. Naturally, this rank requires that the professor hold a Ph.D. in his academic field. Often, these professors have five to 10 years of professorial experience at the postsecondary level. Their work has been published, and they have taken on leadership roles in the campus and the community.

Other Academic Ranks

Teachers who do not hold a Ph.D. but want to teach in higher education can apply for lower-level positions in academia. Instructors and lecturers are titles given to faculty members who have a temporary appointment to teach in a department. For example, a lecturer might come to a university to teach undergraduate courses for a two-year stint. This level of teaching requires a master's degree in the field -- though many instructors and lecturers do hold Ph.D.s.

You can teach at some colleges and universities without a Ph.D. more commonly as a part-time adjunct instructor For example, if you are a CPA who wants to teach bookkeeping at night at your local community college, you can get hired, although the school would prefer that you have at least a master's.

- Bradley University: College Professor Requirements: Steps to Become a Professor

- Indeed: How to Become an Assistant Professor

- North Dakota State University: What Should I Call My Professor?

- The Best Schools: The Hierarchy of Professors, Explained

From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position

I am living the dream.

At least, my professional dream, that is. I have the perfect job for me. And I’m going to share with you how I got it.

First, a little about me. This August, I started my second year of being a tenure-track assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the School of Social Policy & Practice, a program that is consistently ranked in the Top 15 in the country by U.S. News & World Report and one of only two Ivy League social work programs.

As new junior faculty member, I only teach one course each semester so that I have the time to launch my independent program of research. No dumping major course loads on the new assistant professors here! And as with all faculty at my school, I will only ever be required to teach two courses per semester at most, with the option of “buying out” of teaching when I have grant funding.

Additionally, as a new assistant professor, I am given priority selection for the courses I teach, having the school try its best to accommodate my expertise and interest. As soon as I started last year, my dean set up “meet and greets” with key players in my research area in Philadelphia and supported the development and submission of my application for a small, internal grant from the Provost’s Office for the first study in my research portfolio.

I could actually keeping going with why my job is so awesome, but that’s not the point of this article! Instead, I’m going to share what I learned getting to this point—my advice for other PhDs and aspiring professors out there on how to play the academic job search game and win big. Here are five strategies that really boosted my application and helped me land my dream position.

Related: Go to Grad School Guide: PhD Programs

1. Prioritize Publishing

The same publishing rule that echoes through the halls of academia for professors holds true for emerging scholars and newly minted PhDs: “Publish or perish.” A recent article published in The Conversation confirms what I found as true with my own experience: The best predictor of long-term publication success is your early publication record, or the number of papers you’ve published by the time you receive your PhD. And long-term publication success is at the top of the list for what chairs and deans hope their new assistant professors achieve, as this is what ultimately leads to tenure at places like Penn.

In other words, it’s crucial to prioritize publishing now, long before you graduate. I entered my PhD program in 2005, my first two papers came out in 2007, and I published at least two papers per year through my graduation in 2009. When I visited Penn to interview, I had another four papers on my CV , and I know that this early publication success was critical throughout the steps of my candidacy, from the invitation for the conference interview to the campus interview to the job offer.

Of course, a lot of your early publishing success as a PhD student will depend on your research advisor and mentor. I was very fortunate to have a mentor who took great joy in mentoring doctoral students and prioritized getting them involved in paper-writing early on. If you find yourself with someone who is not prioritizing your publication record, however, I recommend having a serious conversation with him or her about your needs and the importance of publishing early—or finding a new mentor. As you probably already know, you have limited time to publish while pursuing your PhD, and the publication process is notorious for taking a very long time to unfold. Prioritize it now.

2. Have a Mission Statement—and Show it Off

My professional mission is to improve the lives for youth who age out of foster care, and I intend to achieve this mission by working to reform the child welfare system so that no youth leaves foster care without a lifetime connection to a caring adult.

Having this mission—and having it spelled out—is what I believe sold my dean during my conference interview. In fact, I provided him and the other two faculty interviewers with a handout of the image below, a visual depiction of the principles and values that guide my mission and a plan for how I intend to achieve it. I think my colleagues were impressed by the fact that I had a visual plan that I could easily explain for how I imagined achieving my professional mission, and also by my creativity. Although a bulleted list could have accomplished the same thing, I believe the packaging made a difference.

Think about how you can explain your own vision and your tactical goals in a compelling way, and be specific about how you’ll make a difference as an assistant professor. For those of us at research-intensive institutions, this will generally take the form of ideas about how you will fund your research mission with grants. If you’re pursuing teaching-oriented places, you can develop a similar vision and mission statement, but make it oriented toward educating, mentoring, and inspiring students.

3. Know the Game

And a game it is. Up until this moment, my experience, probably like many of you, had been that if you work hard, do the right things, and make good choices, you are rewarded—a meritocracy. However, that’s not how the faculty game works (and no one really tells you this)!

Rather, academic hiring decisions are based on “fit,” and if you’re not the right fit, for whatever reason, you won’t receive the offer no matter how impressive your CV is. “Fit” can mean everything from your area of research to what you teach to what a given school may need with respect to faculty demographics and diversity to such mercurial things as faculty personality. Although job postings do tend to detail the research or teaching areas a given school may be looking for, these are often broad, and there can be more than one in a given announcement.

You might think the answer here is to try to be what any particular program wants you to be in order to “fit” in, but I think the real lesson is to take the game for what it is: It’s about them—not about you. Although demonstrating how you see yourself fitting in to a particular program—for example, by showing how your research would complement or add value to a department—is very important to do, in the end, you can’t make a square peg fit a round hole. All you can do is to apply, give it your best shot, and realize that in the end, it’s about them.

4. Have a Plan B

The first time I went on the job market, despite several conference interviews with an array of schools and a successful campus visit and job talk at Michigan, I received no offers. My colleague and fellow new assistant professor Antonio Garcia identified with my experience: “I, too, completed several successful interviews, but to no avail. I did not receive any offers for a tenure track position during my last year of dissertation work.”

So what happened? We both fell back on Plan B: post-doc positions. Although I didn’t want to do a post-doc, it bought me some time and allowed me to further build my CV and professional identity. I went on the market a second time following the first year of my two-year post-doc and was then in an even stronger position than the first time. Professor Garcia also landed his tenure track position following the first year of his post-doc. “Although my first choice was not to delay the tenure clock, it has since worked to my advantage,” he explains. “I benefitted from having time to a meticulously develop my research agenda, publish manuscripts, and develop and maintain long-lasting inter-disciplinary relationships. I strongly believe the two-year post-doc will ultimately provide me with better odds of receiving tenure.”

Fact is, you may not land the assistant professor job of your dreams—or even an assistant professor job—the first time you try. So, it’s incredibly important to have a Plan B, whether that’s a post-doc or a job with a private research firm that still allows you to build your publication record and gain other worthwhile experience that can translate to academia, like presenting your work at professional conferences.

Related: 3 Steps to Turn Any Setback Into a Success

5. Swallow Your Pride

I actually applied to Penn twice—the first time I went on the market I was unsuccessful, but after the first year of my post-doc, I saw another job posting and as best I could tell, I was a good “fit.” I had a bit of a pride issue about knocking on Penn’s door again, but I also realized that if I didn’t, only one thing was certain: I would never work there. So I swallowed my pride, I knocked again, and I landed the job of my dreams. In fact, as I was leaving the hotel suite where I had my conference interview, one of the faculty interviewers said, “I’m so glad you decided to apply again.”

Finding your first professorship isn’t an easy road, but it’s important to persevere and to stay focused on your long-term goals. Penn psychology professor and recently named MacArthur “genius” Fellow Angela Duckworth defines this philosophy as “grit.”

I liken it to surfing. In fact, during my job talk at Penn, while sharing my vision with the hiring committee, I also shared this: “When considering a research-oriented career, a particular quote comes to mind, ‘You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.’ If we think of a research career as the surface of a lake or ocean, there are always waves, sometimes big, sometimes small. Nothing we do can stop the waves, but we can learn to surf.”

There are no guarantees that, even if you do all these things, you will land your dream faculty job. But I hope these tips will help you feel perhaps a little more in control while the waves splash over. Try to have fun with this process, at least as much as you can, and may you, too, soon find yourself living the dream.

Member-only story

The Ultimate Guide to Deciding if You Should Get a PhD and Become a Professor

Zak Slayback

Age of Awareness

This is a guest post by Professor Jason Brennan , the Robert J. and Elizabeth Flanagan Family Professor of Strategy, Economics, Ethics, and Public Policy at the McDonough School of Business and Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University.

He’s also the author of several forthcoming books, including In Defense of Openness , with Bas van der Vossen.

I’ve interviewed Professor Brennan before on how he maintains a prolific output that helps him succeed in academia (to give you an idea, he sent me this article just a few hours after I emailed him requesting it, complete with citations). I asked Professor Brennan to put this together because he’s a great example of how somebody can be successful in academia and he doesn’t sugarcoat what it takes.

Should I Get a PhD and Become a Professor?

TL;DR VERSION: Academia is glorious, but the odds of getting any long-term faculty job, let alone a glorious one, are low. Know the risks and plan accordingly.

Zak recently wrote about the pros and cons of getting a master’s degree .

What if you love the life of the mind and are considering being a college professor?

Written by Zak Slayback

Principal @ 1517 Fund, Author @ McGraw-Hill | Featured in Fast Company & Business Insider- https://zakslayback.com/

Text to speech

How to Become a College Professor: Degrees & Requirements

By Jon Konen, District Superintendent

The truth is, most of that is probably in your head.

The goal of your professors is not to judge you, but to help you learn and expand your potential. It’s a job that comes with a lot of control and freedom, but also involves a real commitment.

Professors are dedicated to knowledge and education. They thrive on teaching and intellectual reasoning and discovery.

Becoming a professor is a dream job if you thrive in the world of theory and knowledge. If your dream is to expand the bounds of human knowledge, to share what you have learned, and to change lives, then a professorship is right up your alley.

Many college professors don’t set out to join that profession. It’s a job that sneaks up on some people. After years studying or working in a field, suddenly the option to teach in that field becomes a viable option. It offers up new opportunities to explore and innovate. Maybe just as important, it’s an opportunity to pass along what you have learned to the next generation of professionals. You can shape your industry, and the world.

Although college professors are definitely educators, that doesn’t mean they need a degree in education. In fact, they flip the script for teaching on its head. They are expected first and foremost to be experts in their own field, and learn pedagogical techniques and principles later on.

This means that becoming a professor doesn’t always follow a straight path, but in a basic sense the process will almost always include these five steps.

How to Become a College Professor in 5 Steps

One unique thing about getting started down the path to learning how to become a college professor is that you don’t really need to take the prescribed steps in order.

Sure, some of them have to come before others—you need an undergraduate degree before anyone will admit you to a PhD program, for example—but otherwise it’s a list of requirements you can check off at almost any stage of your career.

There is enormous competition for these jobs, though. The further you go along to path, the harder each step will become. You’ll need brains, dedication, and a lot of luck to make it all the way to becoming a college professor.

How long does it take to become a college professor?

For the typical pathway to professorship, you can expect a minimum of 8 to 11 years from high school graduation to the front of the lecture hall. But this depends a great deal on your field of study.

Fields that require real-world work experience can add another five years to a decade to your journey. And most professors find their calling along the way, not necessarily pursuing a straight path to the job. Those years of gaining experience and sharpening your skills can add decades to the process.

1. Get a Four-Year Bachelor’s Degree

If you want to teach college, you had better be a college graduate. In every case, that starts with earning a four-year bachelor’s degree.

Because becoming a professor is a long process, with a lot of different paths that can lead to it, your bachelor’s doesn’t necessarily have to be in the field you want to teach in. Many people shift interests through the course of their academic career.

It is important to lay the groundwork for developing your knowledge through education over the long-term. As you’ll see, becoming a professor requires a lot of advanced research and study. Your undergraduate program should equip you with the kind of skills you need to branch out into further learning and research.

Just about any bachelor’s major relevant to your general area of interest can lay the foundation for more advanced study if becoming a professor is your long-term goal.

Want to become a professor of education? Then it’s going to take a degree in education to get you started down the right path. Ready to take the next step? Find teaching degree programs near you!

2. Earn an Advanced Degree in Your Area of Expertise

To teach any material at the college level, you need a deep understanding of the theory and concepts behind it. That’s always going to mean earning an advanced degree in the subject.

Research can be an important part of professorial work, and master’s and doctoral level programs are exactly where you learn how to do that work.

The research required as part of your studies, and eventually your thesis and dissertation projects, are also a primary way for you to develop an advanced understanding of your field.

This is also an important time to cultivate mentors and relationships in your field. When you get to the point where you are applying for positions, you’ll find that the academic field is a pretty small community, so who you know matters.

Your professors in grad school will know people on the hiring committees at the colleges and universities where you will be interviewing later on. If you impressed them, you can expect a good word in the right ears.

What degree do you need to be a college professor? … Does a college professor need a PhD?

The PhD, or Doctor of Philosophy, has long been the standard degree requirement for college professors. Many community colleges and other two-year schools may require only a master’s degree, however. There are also certain areas of study where a PhD is not considered necessary, such as acting and music. Almost all traditional academic departments at four-year universities definitely prefer to higher doctoral graduates as professors, however.

For example, you’ll want to earn a doctorate in education if you plan to become a professor of education.

Can you be a professor with a master’s degree?

It’s most common to find professors teaching with only a master’s degree at the community college level, or working as adjunct faculty at four-year colleges. Adjuncts are the academic version of temps, but they make up the majority of faculty in American universities. According to NCES, in 2018, 54 percent of instructors at degree-granting post-secondary institutions were adjunct faculty.

In many fields, however, there is a surplus of PhD graduates, which makes competition stiff even for adjunct positions. In these fields, a master’s-level professor position is rare.

3. Build Real-world Experience in Your Field

But if you’re aiming to be a professor in journalism, medicine, engineering, or just about any other field with practical applications, most colleges want to see that you have what it takes to do what you will teach . That means holding down a job and racking up some accomplishments to build up that CV you’ll be submitting to the hiring committee.

Colleges and universities actively seek out professors who have expertise in cutting-edge subjects in their field. You’ll want to look for jobs that will give you experience in the kinds of topics that will be most important to the future of your field. That’s exactly what students are going to come to school to learn.

How To Be a College Professor Without a PhD

The drive to be the school with the most cutting-edge curriculum in a given field is one that can push hiring committees away from that PhD standard. If you can develop the right expertise, and a reputation to match, then it’s possible you can meet the college professor requirements without having a doctorate.

If there is big demand for professors in a particular field, you can sometimes find temporary work with only a master’s degree. If you earn a master’s degree in education , for example, you might be able to get a job instructing teachers as an adjunct professor.

It’s also much easier to become a professor without a PhD if you want to teach in a field where PhDs aren’t the standard mark of expertise. Arts programs, for example, generally show preference to instructors with experience and expertise over those with impressive academic credentials who may not have a lot of experience because the paths to those industries often don’t run through college.

4. Get Hired as a College Professor

Once you have the experience and the education to become qualified, you can start hunting for jobs teaching in college classrooms.

At first, you’ll almost certainly start as an adjunct, teaching part-time or in a visiting position at community colleges or small universities. Since there are no real professional pedagogical standards in college instruction, this serves as a sort of apprenticeship where you cut your teeth learning how to actually transfer your knowledge to students.

At the entry level, college professors don’t have a lot of options in the job market. You will very likely have to relocate to an area with a school willing to hire you. You’ll go through a lot of interviews and apply to a lot of positions to get your foot in the door.

The process and timing will vary from field to field. Many have specialized publications, like PhilJobs.org for philosophy positions, where openings are posted.

Your qualifications and specialties are very important. Schools are often looking for very specific areas of expertise to shore up their existing faculty range. Frequently, the pedigree of your education will matter. A degree from a big-name school gets you further than a small state college no one has ever heard of.

Different colleges and different departments within those colleges have different priorities when it comes to hiring. At research driven institutions, your record of exploration and publication may be all-important. At schools that value teaching, your classroom expertise will be more valued.

What qualifications do you need to be a professor?

Though a master’s to start, and then eventually earning a doctorate, is the general rule for full-time tenure positions, here are no state or national standards for teaching college. The question is only truly answered by college hiring committees. Every school is different. They value different qualities ranging from research experience to real-world know-how. And it can differ from job to job or even year to year.

The most important quality you need when figuring out how to become a college professor may be your desire to learn. If you want to get your students interested in the material, you need to live and breathe it yourself. Academia is all about the process of expanding and understanding new knowledge. You’ll never fit into the field if you don’t have a passion for that.

5. Earn Tenure at Your University

Tenure is the end of the line for college professors. While almost any other kind of job can fire you with or without cause, once a professor has tenure, they are all but assured a position for life. Tenure insulates the academic community from trends and fads, allowing unpopular opinions to be expressed and unusual lines of research to be pursued. These are the hallmarks of liberal thinking and a liberal education.

But you have to earn that kind of freedom.

That first involves getting a fixed-term contract that offers possible tenure. It probably won’t be your first professorship, so you can expect to jump around between a few schools before it comes up.

That contract will mark you as an assistant professor, starting the long road to tenure. You will teach for a few years at that level, being observed by your department and undergoing evaluation by both students and other professors.

Assuming you survive that process, you will earn promotion to associate professor. This means a salary bump but also increased scrutiny for several more years. Your teaching, research, and publication accomplishments will all be weighed during this period. You may also take on additional administrative responsibilities in your department, and be evaluated in your performance.

In the end, a tenure committee of other faculty will decide whether or not you are worthy of becoming a full tenured professor.

Do professors make good money?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2020 the median salary for postsecondary teachers, the category that college professors are included in, was $80,790 per year.

But that also includes educators at vocational schools and other training academies outside of traditional colleges. The top ten percent of the group make excellent money, over $180,360 per year. The field you teach in can also affect your salary, with in-demand areas like law, economics, and engineering commanding six-figure median salaries.

Is a college professor a good career?

Like any career, becoming a college professor can be great if it delivers what you are looking for in a job. It’s perfect for people who enjoy exploring intellectual ideas, passing them on to students, engaging in cutting-edge research, and discussing it with other academics. Professors have tremendous flexibility in their personal schedules and in their freedom to teach topics that interest them. They have to be self-motivated and enjoy engaging with students. The opportunity to take long sabbaticals without risk of losing your job is also a big benefit that many enjoy.

How to become a professor

CareerExplorer’s step-by-step guide on how to become a professor.

Is becoming a professor right for me?

The first step to choosing a career is to make sure you are actually willing to commit to pursuing the career. You don’t want to waste your time doing something you don’t want to do. If you’re new here, you should read about:

Still unsure if becoming a professor is the right career path? Take the free CareerExplorer career test to find out if this career is right for you. Perhaps you are well-suited to become a professor or another similar career!

Described by our users as being “shockingly accurate”, you might discover careers you haven’t thought of before.

High School

Becoming a professor involves a significant educational journey, typically culminating in a doctoral degree. While high school courses directly don't lead to becoming a professor, they can lay a strong foundation for your future academic and career pursuits. Here are some high school courses that can help prepare you for a path toward becoming a professor:

- Advanced Placement (AP) Courses: Taking AP courses in subjects like English, mathematics, science, social studies, and foreign languages can provide you with a rigorous academic foundation and potentially earn you college credit.

- Mathematics and Sciences: Courses in subjects like mathematics, biology, chemistry, and physics can help develop critical thinking, analytical skills, and a strong scientific foundation that can be beneficial for many academic fields.

- Social Sciences and Humanities: Courses in history, economics, psychology, philosophy, and literature can cultivate your analytical and critical thinking abilities, which are essential skills for academic research and writing.

- Foreign Languages: Learning a foreign language can expand your cultural awareness, communication skills, and research opportunities, especially if you plan to work in international academic contexts.

- Research Skills: If your high school offers courses or extracurricular activities related to research, science projects, or debate, participating in these can help develop your research, analytical, and communication skills.

- Writing and Communication: Strong writing and communication skills are vital for academic success. English courses and extracurricular activities like debate, public speaking, and writing clubs can help hone these skills.

- Computer Science and Technology: Proficiency in technology is increasingly important in academia. Taking computer science courses or exploring coding and programming can be valuable, especially for fields involving data analysis and research.

- Leadership and Extracurricular Activities: Participating in leadership roles in clubs, student government, or community service can demonstrate your ability to lead and collaborate, which are essential for academic roles.

Steps to Become a Professor

Becoming a professor is a significant achievement that requires dedication, perseverance, and a commitment to advancing knowledge and education in your chosen field. The process is challenging, but the impact you can make on students and your field of study can be immensely rewarding.

Here's a detailed overview of the process:

- Obtain a Bachelor's Degree - Start by completing a bachelor's degree in your chosen field of study. Select a major that aligns with the area you wish to specialize in as a professor. During your undergraduate years, focus on achieving a high GPA, building strong relationships with professors, and gaining research or teaching experience through internships, research projects, or teaching assistant roles.

- Pursue a Master's Degree (Optional) - While not always required, some fields and universities may recommend or require a master's degree for aspiring professors. If your field values advanced education, pursue a master's program that provides in-depth knowledge and research experience. It's important to research the expectations within your specific field.