Home » Tips for Teachers » 7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

In recent years, the question of why students should not have homework has become a topic of intense debate among educators, parents, and students themselves. This discussion stems from a growing body of research that challenges the traditional view of homework as an essential component of academic success. The notion that homework is an integral part of learning is being reevaluated in light of new findings about its effectiveness and impact on students’ overall well-being.

The push against homework is not just about the hours spent on completing assignments; it’s about rethinking the role of education in fostering the well-rounded development of young individuals. Critics argue that homework, particularly in excessive amounts, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout, and a diminished love for learning. Moreover, it often disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating educational inequities. The debate also highlights the importance of allowing children to have enough free time for play, exploration, and family interaction, which are crucial for their social and emotional development.

Checking 13yo’s math homework & I have just one question. I can catch mistakes & help her correct. But what do kids do when their parent isn’t an Algebra teacher? Answer: They get frustrated. Quit. Get a bad grade. Think they aren’t good at math. How is homework fair??? — Jay Wamsted (@JayWamsted) March 24, 2022

As we delve into this discussion, we explore various facets of why reducing or even eliminating homework could be beneficial. We consider the research, weigh the pros and cons, and examine alternative approaches to traditional homework that can enhance learning without overburdening students.

Once you’ve finished this article, you’ll know:

- Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts →

- 7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework →

- Opposing Views on Homework Practices →

- Exploring Alternatives to Homework →

Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts: Diverse Perspectives on Homework

In the ongoing conversation about the role and impact of homework in education, the perspectives of those directly involved in the teaching process are invaluable. Teachers and education industry experts bring a wealth of experience and insights from the front lines of learning. Their viewpoints, shaped by years of interaction with students and a deep understanding of educational methodologies, offer a critical lens through which we can evaluate the effectiveness and necessity of homework in our current educational paradigm.

Check out this video featuring Courtney White, a high school language arts teacher who gained widespread attention for her explanation of why she chooses not to assign homework.

Here are the insights and opinions from various experts in the educational field on this topic:

“I teach 1st grade. I had parents ask for homework. I explained that I don’t give homework. Home time is family time. Time to play, cook, explore and spend time together. I do send books home, but there is no requirement or checklist for reading them. Read them, enjoy them, and return them when your child is ready for more. I explained that as a parent myself, I know they are busy—and what a waste of energy it is to sit and force their kids to do work at home—when they could use that time to form relationships and build a loving home. Something kids need more than a few math problems a week.” — Colleen S. , 1st grade teacher

“The lasting educational value of homework at that age is not proven. A kid says the times tables [at school] because he studied the times tables last night. But over a long period of time, a kid who is drilled on the times tables at school, rather than as homework, will also memorize their times tables. We are worried about young children and their social emotional learning. And that has to do with physical activity, it has to do with playing with peers, it has to do with family time. All of those are very important and can be removed by too much homework.” — David Bloomfield , education professor at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York graduate center

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’” — John Hattie , professor

”Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll – psychologically and in many other ways too. We see kids getting up hours before school starts just to get their homework done from the night before… While homework may give kids one more responsibility, it ignores the fact that kids do not need to grow up and become adults at ages 10 or 12. With schools cutting recess time or eliminating playgrounds, kids absorb every single stress there is, only on an even higher level. Their brains and bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.” — Pat Wayman, teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com

7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Let’s delve into the reasons against assigning homework to students. Examining these arguments offers important perspectives on the wider educational and developmental consequences of homework practices.

1. Elevated Stress and Health Consequences

The ongoing debate about homework often focuses on its educational value, but a vital aspect that cannot be overlooked is the significant stress and health consequences it brings to students. In the context of American life, where approximately 70% of people report moderate or extreme stress due to various factors like mass shootings, healthcare affordability, discrimination, racism, sexual harassment, climate change, presidential elections, and the need to stay informed, the additional burden of homework further exacerbates this stress, particularly among students.

Key findings and statistics reveal a worrying trend:

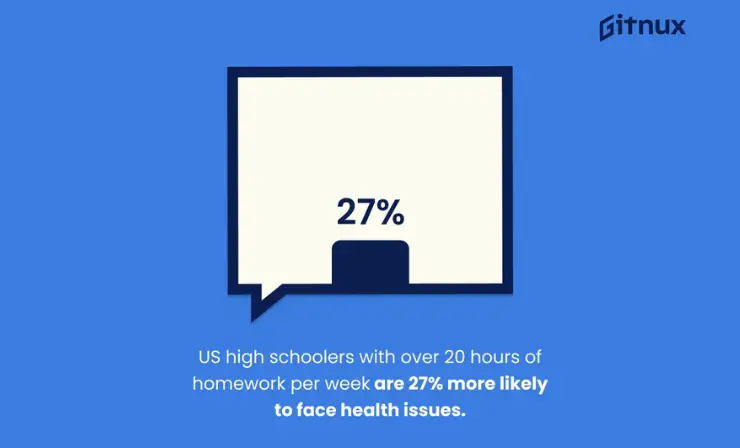

- Overwhelming Student Stress: A staggering 72% of students report being often or always stressed over schoolwork, with a concerning 82% experiencing physical symptoms due to this stress.

- Serious Health Issues: Symptoms linked to homework stress include sleep deprivation, headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems.

- Sleep Deprivation: Despite the National Sleep Foundation recommending 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep for healthy adolescent development, students average just 6.80 hours of sleep on school nights. About 68% of students stated that schoolwork often or always prevented them from getting enough sleep, which is critical for their physical and mental health.

- Turning to Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Alarmingly, the pressure from excessive homework has led some students to turn to alcohol and drugs as a way to cope with stress.

This data paints a concerning picture. Students, already navigating a world filled with various stressors, find themselves further burdened by homework demands. The direct correlation between excessive homework and health issues indicates a need for reevaluation. The goal should be to ensure that homework if assigned, adds value to students’ learning experiences without compromising their health and well-being.

By addressing the issue of homework-related stress and health consequences, we can take a significant step toward creating a more nurturing and effective educational environment. This environment would not only prioritize academic achievement but also the overall well-being and happiness of students, preparing them for a balanced and healthy life both inside and outside the classroom.

2. Inequitable Impact and Socioeconomic Disparities

In the discourse surrounding educational equity, homework emerges as a factor exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, particularly affecting students from lower-income families and those with less supportive home environments. While homework is often justified as a means to raise academic standards and promote equity, its real-world impact tells a different story.

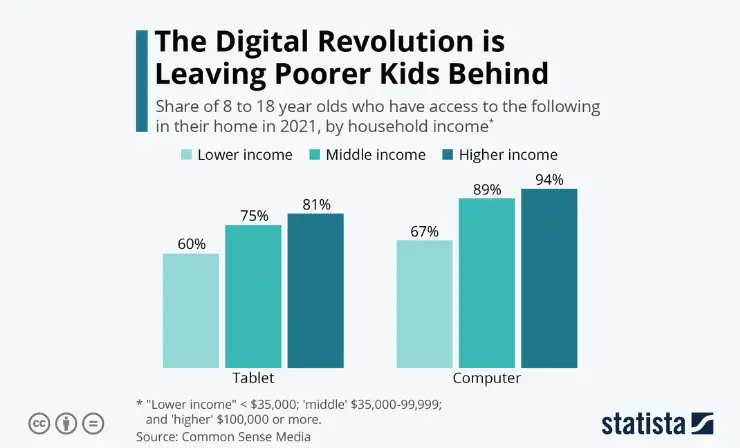

The inequitable burden of homework becomes starkly evident when considering the resources required to complete it, especially in the digital age. Homework today often necessitates a computer and internet access – resources not readily available to all students. This digital divide significantly disadvantages students from lower-income backgrounds, deepening the chasm between them and their more affluent peers.

Key points highlighting the disparities:

- Digital Inequity: Many students lack access to necessary technology for homework, with low-income families disproportionately affected.

- Impact of COVID-19: The pandemic exacerbated these disparities as education shifted online, revealing the extent of the digital divide.

- Educational Outcomes Tied to Income: A critical indicator of college success is linked more to family income levels than to rigorous academic preparation. Research indicates that while 77% of students from high-income families graduate from highly competitive colleges, only 9% from low-income families achieve the same . This disparity suggests that the pressure of heavy homework loads, rather than leveling the playing field, may actually hinder the chances of success for less affluent students.

Moreover, the approach to homework varies significantly across different types of schools. While some rigorous private and preparatory schools in both marginalized and affluent communities assign extreme levels of homework, many progressive schools focusing on holistic learning and self-actualization opt for no homework, yet achieve similar levels of college and career success. This contrast raises questions about the efficacy and necessity of heavy homework loads in achieving educational outcomes.

The issue of homework and its inequitable impact is not just an academic concern; it is a reflection of broader societal inequalities. By continuing practices that disproportionately burden students from less privileged backgrounds, the educational system inadvertently perpetuates the very disparities it seeks to overcome.

3. Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

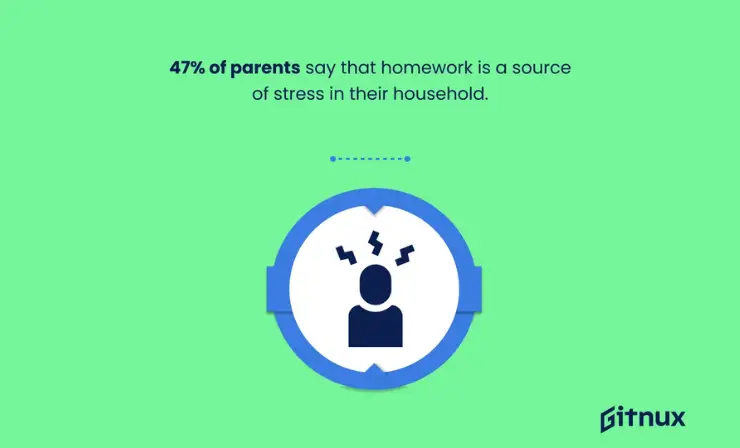

Homework, a staple of the educational system, is often perceived as a necessary tool for academic reinforcement. However, its impact extends beyond the realm of academics, significantly affecting family dynamics. The negative repercussions of homework on the home environment have become increasingly evident, revealing a troubling pattern that can lead to conflict, mental health issues, and domestic friction.

A study conducted in 2015 involving 1,100 parents sheds light on the strain homework places on family relationships. The findings are telling:

- Increased Likelihood of Conflicts: Families where parents did not have a college degree were 200% more likely to experience fights over homework.

- Misinterpretations and Misunderstandings: Parents often misinterpret their children’s difficulties with homework as a lack of attention in school, leading to feelings of frustration and mistrust on both sides.

- Discriminatory Impact: The research concluded that the current approach to homework disproportionately affects children whose parents have lower educational backgrounds, speak English as a second language, or belong to lower-income groups.

The issue is not confined to specific demographics but is a widespread concern. Samantha Hulsman, a teacher featured in Education Week Teacher , shared her personal experience with the toll that homework can take on family time. She observed that a seemingly simple 30-minute assignment could escalate into a three-hour ordeal, causing stress and strife between parents and children. Hulsman’s insights challenge the traditional mindset about homework, highlighting a shift towards the need for skills such as collaboration and problem-solving over rote memorization of facts.

The need of the hour is to reassess the role and amount of homework assigned to students. It’s imperative to find a balance that facilitates learning and growth without compromising the well-being of the family unit. Such a reassessment would not only aid in reducing domestic conflicts but also contribute to a more supportive and nurturing environment for children’s overall development.

4. Consumption of Free Time

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices has raised concerns about the excessive burden of homework on students, emphasizing how it consumes their free time and impedes their overall well-being. The issue is not just the quantity of homework, but its encroachment on time that could be used for personal growth, relaxation, and family bonding.

Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish , in their book “The Case Against Homework,” offer an insightful window into the lives of families grappling with the demands of excessive homework. They share stories from numerous interviews conducted in the mid-2000s, highlighting the universal struggle faced by families across different demographics. A poignant account from a parent in Menlo Park, California, describes nightly sessions extending until 11 p.m., filled with stress and frustration, leading to a soured attitude towards school in both the child and the parent. This narrative is not isolated, as about one-third of the families interviewed expressed feeling crushed by the overwhelming workload.

Key points of concern:

- Excessive Time Commitment: Students, on average, spend over 6 hours in school each day, and homework adds significantly to this time, leaving little room for other activities.

- Impact on Extracurricular Activities: Homework infringes upon time for sports, music, art, and other enriching experiences, which are as crucial as academic courses.

- Stifling Creativity and Self-Discovery: The constant pressure of homework limits opportunities for students to explore their interests and learn new skills independently.

The National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA) recommend a “10 minutes of homework per grade level” standard, suggesting a more balanced approach. However, the reality often far exceeds this guideline, particularly for older students. The impact of this overreach is profound, affecting not just academic performance but also students’ attitudes toward school, their self-confidence, social skills, and overall quality of life.

Furthermore, the intense homework routine’s effectiveness is doubtful, as it can overwhelm students and detract from the joy of learning. Effective learning builds on prior knowledge in an engaging way, but excessive homework in a home setting may be irrelevant and uninteresting. The key challenge is balancing homework to enhance learning without overburdening students, allowing time for holistic growth and activities beyond academics. It’s crucial to reassess homework policies to support well-rounded development.

5. Challenges for Students with Learning Disabilities

Homework, a standard educational tool, poses unique challenges for students with learning disabilities, often leading to a frustrating and disheartening experience. These challenges go beyond the typical struggles faced by most students and can significantly impede their educational progress and emotional well-being.

Child psychologist Kenneth Barish’s insights in Psychology Today shed light on the complex relationship between homework and students with learning disabilities:

- Homework as a Painful Endeavor: For students with learning disabilities, completing homework can be likened to “running with a sprained ankle.” It’s a task that, while doable, is fraught with difficulty and discomfort.

- Misconceptions about Laziness: Often, children who struggle with homework are perceived as lazy. However, Barish emphasizes that these students are more likely to be frustrated, discouraged, or anxious rather than unmotivated.

- Limited Improvement in School Performance: The battles over homework rarely translate into significant improvement in school for these children, challenging the conventional notion of homework as universally beneficial.

These points highlight the need for a tailored approach to homework for students with learning disabilities. It’s crucial to recognize that the traditional homework model may not be the most effective or appropriate method for facilitating their learning. Instead, alternative strategies that accommodate their unique needs and learning styles should be considered.

In conclusion, the conventional homework paradigm needs reevaluation, particularly concerning students with learning disabilities. By understanding and addressing their unique challenges, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. This approach not only aids in their academic growth but also nurtures their confidence and overall development, ensuring that they receive an equitable and empathetic educational experience.

6. Critique of Underlying Assumptions about Learning

The longstanding belief in the educational sphere that more homework automatically translates to more learning is increasingly being challenged. Critics argue that this assumption is not only flawed but also unsupported by solid evidence, questioning the efficacy of homework as an effective learning tool.

Alfie Kohn , a prominent critic of homework, aptly compares students to vending machines in this context, suggesting that the expectation of inserting an assignment and automatically getting out of learning is misguided. Kohn goes further, labeling homework as the “greatest single extinguisher of children’s curiosity.” This critique highlights a fundamental issue: the potential of homework to stifle the natural inquisitiveness and love for learning in children.

The lack of concrete evidence supporting the effectiveness of homework is evident in various studies:

- Marginal Effectiveness of Homework: A study involving 28,051 high school seniors found that the effectiveness of homework was marginal, and in some cases, it was counterproductive, leading to more academic problems than solutions.

- No Correlation with Academic Achievement: Research in “ National Differences, Global Similarities ” showed no correlation between homework and academic achievement in elementary students, and any positive correlation in middle or high school diminished with increasing homework loads.

- Increased Academic Pressure: The Teachers College Record published findings that homework adds to academic pressure and societal stress, exacerbating performance gaps between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

These findings bring to light several critical points:

- Quality Over Quantity: According to a recent article in Monitor on Psychology , experts concur that the quality of homework assignments, along with the quality of instruction, student motivation, and inherent ability, is more crucial for academic success than the quantity of homework.

- Counterproductive Nature of Excessive Homework: Excessive homework can lead to more academic challenges, particularly for students already facing pressures from other aspects of their lives.

- Societal Stress and Performance Gaps: Homework can intensify societal stress and widen the academic performance divide.

The emerging consensus from these studies suggests that the traditional approach to homework needs rethinking. Rather than focusing on the quantity of assignments, educators should consider the quality and relevance of homework, ensuring it truly contributes to learning and development. This reassessment is crucial for fostering an educational environment that nurtures curiosity and a love for learning, rather than extinguishing it.

7. Issues with Homework Enforcement, Reliability, and Temptation to Cheat

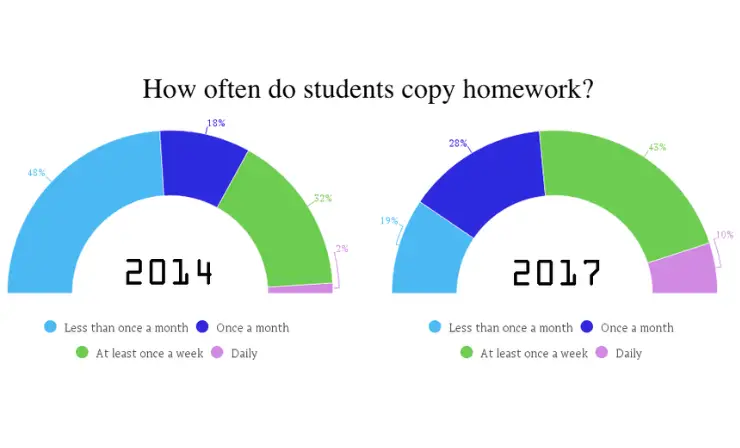

In the academic realm, the enforcement of homework is a subject of ongoing debate, primarily due to its implications on student integrity and the true value of assignments. The challenges associated with homework enforcement often lead to unintended yet significant issues, such as cheating, copying, and a general undermining of educational values.

Key points highlighting enforcement challenges:

- Difficulty in Enforcing Completion: Ensuring that students complete their homework can be a complex task, and not completing homework does not always correlate with poor grades.

- Reliability of Homework Practice: The reliability of homework as a practice tool is undermined when students, either out of desperation or lack of understanding, choose shortcuts over genuine learning. This approach can lead to the opposite of the intended effect, especially when assignments are not well-aligned with the students’ learning levels or interests.

- Temptation to Cheat: The issue of cheating is particularly troubling. According to a report by The Chronicle of Higher Education , under the pressure of at-home assignments, many students turn to copying others’ work, plagiarizing, or using creative technological “hacks.” This tendency not only questions the integrity of the learning process but also reflects the extreme stress that homework can induce.

- Parental Involvement in Completion: As noted in The American Journal of Family Therapy , this raises concerns about the authenticity of the work submitted. When parents complete assignments for their children, it not only deprives the students of the opportunity to learn but also distorts the purpose of homework as a learning aid.

In conclusion, the challenges of homework enforcement present a complex problem that requires careful consideration. The focus should shift towards creating meaningful, manageable, and quality-driven assignments that encourage genuine learning and integrity, rather than overwhelming students and prompting counterproductive behaviors.

Addressing Opposing Views on Homework Practices

While opinions on homework policies are diverse, understanding different viewpoints is crucial. In the following sections, we will examine common arguments supporting homework assignments, along with counterarguments that offer alternative perspectives on this educational practice.

1. Improvement of Academic Performance

Homework is commonly perceived as a means to enhance academic performance, with the belief that it directly contributes to better grades and test scores. This view posits that through homework, students reinforce what they learn in class, leading to improved understanding and retention, which ultimately translates into higher academic achievement.

However, the question of why students should not have homework becomes pertinent when considering the complex relationship between homework and academic performance. Studies have indicated that excessive homework doesn’t necessarily equate to higher grades or test scores. Instead, too much homework can backfire, leading to stress and fatigue that adversely affect a student’s performance. Reuters highlights an intriguing correlation suggesting that physical activity may be more conducive to academic success than additional homework, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach to education that prioritizes both physical and mental well-being for enhanced academic outcomes.

2. Reinforcement of Learning

Homework is traditionally viewed as a tool to reinforce classroom learning, enabling students to practice and retain material. However, research suggests its effectiveness is ambiguous. In instances where homework is well-aligned with students’ abilities and classroom teachings, it can indeed be beneficial. Particularly for younger students , excessive homework can cause burnout and a loss of interest in learning, counteracting its intended purpose.

Furthermore, when homework surpasses a student’s capability, it may induce frustration and confusion rather than aid in learning. This challenges the notion that more homework invariably leads to better understanding and retention of educational content.

3. Development of Time Management Skills

Homework is often considered a crucial tool in helping students develop important life skills such as time management and organization. The idea is that by regularly completing assignments, students learn to allocate their time efficiently and organize their tasks effectively, skills that are invaluable in both academic and personal life.

However, the impact of homework on developing these skills is not always positive. For younger students, especially, an overwhelming amount of homework can be more of a hindrance than a help. Instead of fostering time management and organizational skills, an excessive workload often leads to stress and anxiety . These negative effects can impede the learning process and make it difficult for students to manage their time and tasks effectively, contradicting the original purpose of homework.

4. Preparation for Future Academic Challenges

Homework is often touted as a preparatory tool for future academic challenges that students will encounter in higher education and their professional lives. The argument is that by tackling homework, students build a foundation of knowledge and skills necessary for success in more advanced studies and in the workforce, fostering a sense of readiness and confidence.

Contrarily, an excessive homework load, especially from a young age, can have the opposite effect . It can instill a negative attitude towards education, dampening students’ enthusiasm and willingness to embrace future academic challenges. Overburdening students with homework risks disengagement and loss of interest, thereby defeating the purpose of preparing them for future challenges. Striking a balance in the amount and complexity of homework is crucial to maintaining student engagement and fostering a positive attitude towards ongoing learning.

5. Parental Involvement in Education

Homework often acts as a vital link connecting parents to their child’s educational journey, offering insights into the school’s curriculum and their child’s learning process. This involvement is key in fostering a supportive home environment and encouraging a collaborative relationship between parents and the school. When parents understand and engage with what their children are learning, it can significantly enhance the educational experience for the child.

However, the line between involvement and over-involvement is thin. When parents excessively intervene by completing their child’s homework, it can have adverse effects . Such actions not only diminish the educational value of homework but also rob children of the opportunity to develop problem-solving skills and independence. This over-involvement, coupled with disparities in parental ability to assist due to variations in time, knowledge, or resources, may lead to unequal educational outcomes, underlining the importance of a balanced approach to parental participation in homework.

Exploring Alternatives to Homework and Finding a Middle Ground

In the ongoing debate about the role of homework in education, it’s essential to consider viable alternatives and strategies to minimize its burden. While completely eliminating homework may not be feasible for all educators, there are several effective methods to reduce its impact and offer more engaging, student-friendly approaches to learning.

Alternatives to Traditional Homework

- Project-Based Learning: This method focuses on hands-on, long-term projects where students explore real-world problems. It encourages creativity, critical thinking, and collaborative skills, offering a more engaging and practical learning experience than traditional homework. For creative ideas on school projects, especially related to the solar system, be sure to explore our dedicated article on solar system projects .

- Flipped Classrooms: Here, students are introduced to new content through videos or reading materials at home and then use class time for interactive activities. This approach allows for more personalized and active learning during school hours.

- Reading for Pleasure: Encouraging students to read books of their choice can foster a love for reading and improve literacy skills without the pressure of traditional homework assignments. This approach is exemplified by Marion County, Florida , where public schools implemented a no-homework policy for elementary students. Instead, they are encouraged to read nightly for 20 minutes . Superintendent Heidi Maier’s decision was influenced by research showing that while homework offers minimal benefit to young students, regular reading significantly boosts their learning. For book recommendations tailored to middle school students, take a look at our specially curated article .

Ideas for Minimizing Homework

- Limiting Homework Quantity: Adhering to guidelines like the “ 10-minute rule ” (10 minutes of homework per grade level per night) can help ensure that homework does not become overwhelming.

- Quality Over Quantity: Focus on assigning meaningful homework that is directly relevant to what is being taught in class, ensuring it adds value to students’ learning.

- Homework Menus: Offering students a choice of assignments can cater to diverse learning styles and interests, making homework more engaging and personalized.

- Integrating Technology: Utilizing educational apps and online platforms can make homework more interactive and enjoyable, while also providing immediate feedback to students. To gain deeper insights into the role of technology in learning environments, explore our articles discussing the benefits of incorporating technology in classrooms and a comprehensive list of educational VR apps . These resources will provide you with valuable information on how technology can enhance the educational experience.

For teachers who are not ready to fully eliminate homework, these strategies offer a compromise, ensuring that homework supports rather than hinders student learning. By focusing on quality, relevance, and student engagement, educators can transform homework from a chore into a meaningful component of education that genuinely contributes to students’ academic growth and personal development. In this way, we can move towards a more balanced and student-centric approach to learning, both in and out of the classroom.

Useful Resources

- Is homework a good idea or not? by BBC

- The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype

- Alternative Homework Ideas

The evidence and arguments presented in the discussion of why students should not have homework call for a significant shift in homework practices. It’s time for educators and policymakers to rethink and reformulate homework strategies, focusing on enhancing the quality, relevance, and balance of assignments. By doing so, we can create a more equitable, effective, and student-friendly educational environment that fosters learning, well-being, and holistic development.

- “Here’s what an education expert says about that viral ‘no-homework’ policy”, Insider

- “John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”, Visible Learning

- HowtoLearn.com

- “Time Spent On Homework Statistics [Fresh Research]”, Gitnux

- “Stress in America”, American Psychological Association (APA)

- “Homework hurts high-achieving students, study says”, The Washington Post

- “National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report”, National Library of Medicine

- “A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools”, Frontiers

- “The Digital Revolution is Leaving Poorer Kids Behind”, Statista

- “The digital divide has left millions of school kids behind”, CNET

- “The Digital Divide: What It Is, and What’s Being Done to Close It”, Investopedia

- “COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it”, World Economic Forum

- “PBS NewsHour: Biggest Predictor of College Success is Family Income”, America’s Promise Alliance

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, Taylor & Francis Online

- “What Do You Mean My Kid Doesn’t Have Homework?”, EducationWeek

- “Excerpt From The Case Against Homework”, Penguin Random House Canada

- “How much homework is too much?”, neaToday

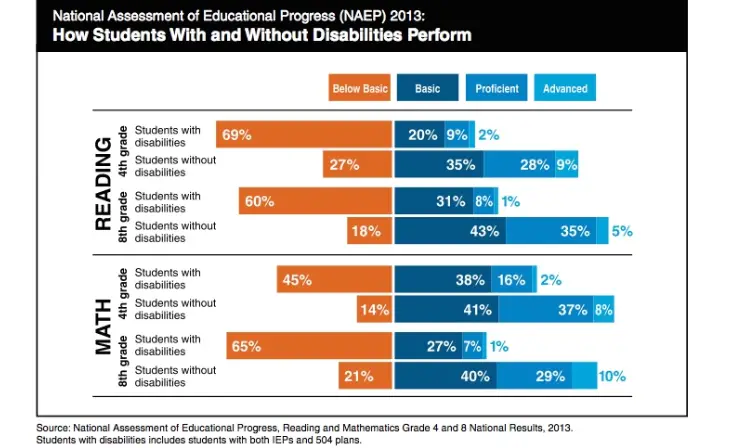

- “The Nation’s Report Card: A First Look: 2013 Mathematics and Reading”, National Center for Education Statistics

- “Battles Over Homework: Advice For Parents”, Psychology Today

- “How Homework Is Destroying Teens’ Health”, The Lion’s Roar

- “ Breaking the Homework Habit”, Education World

- “Testing a model of school learning: Direct and indirect effects on academic achievement”, ScienceDirect

- “National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling”, Stanford University Press

- “When school goes home: Some problems in the organization of homework”, APA PsycNet

- “Is homework a necessary evil?”, APA PsycNet

- “Epidemic of copying homework catalyzed by technology”, Redwood Bark

- “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame”, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, ResearchGate

- “Kids who get moving may also get better grades”, Reuters

- “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003”, SageJournals

- “Is it time to get rid of homework?”, USAToday

- “Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework”, Stanford

- “Florida school district bans homework, replaces it with daily reading”, USAToday

- “Encouraging Students to Read: Tips for High School Teachers”, wgu.edu

- Recent Posts

Simona Johnes is the visionary being the creation of our project. Johnes spent much of her career in the classroom working with students. And, after many years in the classroom, Johnes became a principal.

- Overview of 22 Low-Code Agencies for MVP, Web, or Mobile App Development - October 23, 2024

- Tips to Inspire Your Young Child to Pursue a Career in Nursing - July 24, 2024

- How Parents Can Advocate for Their Children’s Journey into Forensic Nursing - July 24, 2024

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Rick Hess Straight Up

Education policy maven Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute think tank offers straight talk on matters of policy, politics, research, and reform. Read more from this blog.

What Many Advocates—and Critics—Get Wrong About ‘Equitable Grading’

- Share article

Joe Feldman is a former high school teacher, principal, and district administrator and the author of Grading for Equity , now in its second edition. He’s also the CEO of Crescendo Education Group , which works with schools and systems on grading practices. Well, Joe reached out after a recent RHSU post in which I expressed my concerns about “equitable grading.” While we haven’t been in touch in a long time, I’ve known Joe since I TA’d a class he was in at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education 30 years ago. We wound up having a pretty fruitful exchange that, with Joe’s blessing, I thought worth sharing.

Joe: Rick, you’ve written recently about the harms of grade inflation and how a primary cause is educators who, influenced by “equitable grading,” compromise rigor and award students higher grades than they deserve. As someone who has researched equitable grading, written about it, and worked with hundreds of teachers to understand and implement the practices for it over a decade, I wanted to share some thoughts and explain that there are some common misunderstandings about equitable grading. One of the biggest is that the goal is simply to raise grades. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, a goal of equitable grading is actually to reduce grade inflation.

Rick: Thanks for reaching out. OK, I’m intrigued. While I’ve heard a lot of advocates and educators talk about equitable grading, I don’t recall any raising concerns about grade inflation. They’ve mostly urged policies that are less stringent and more forgiving, while sounding skeptical about traditional norms like hard work and personal responsibility. And, as I think you know, I rather like those traditional values. I fear that easy grading sends the wrong signal to students, gives a false sense of confidence to parents, and makes it tougher for teachers to maintain rigorous expectations. So, I’m delighted to hear you say that equitable grading isn’t at odds with all that. Tell me more.

Joe: OK, so the bottom line is that you and I both want the same thing: We want to be confident that the integrity of a student’s grade isn’t compromised by a teacher’s opinion or emotions about a student. Teachers can be tempted to reduce expectations for some students out of a heartfelt empathy for those with challenging backgrounds or circumstances. The student whose family is unhoused, has responsibilities to care for younger siblings, has ill family members, or lives amid daily violence all deserve care and support. Of course, we want our teachers to be compassionate and caring for each student, particularly those who face struggles outside their control, but unfortunately, teachers’ empathy can be misplaced when they give students grades that are higher than their true course content understanding.

Equitable grading presumes that our students and their families deserve dignity and respect, which means we must always be honest and accurate in our communication about where they are in their learning. One of the least equitable things we can do is mislead students by assigning them inflated grades and false descriptions of their performance, because doing so sets them up for a rude awakening and possible future failures. Equitable grading means accurately describing their achievement and channeling empathy for students—not into reduced expectations but through actions that truly improve their learning: additional supports, relevant and engaging curriculum and instruction, and multiple pathways to access and demonstrate learning.

Rick: OK, so I’m mostly nodding along here. I get honest and accurate information as a sign of respect for students and families. And I buy the problems you describe with easy grades and misleading feedback. And yet I’m used to hearing such concerns brushed off by those who champion equitable grading. So, what’s up? Why is the common sense you’re offering here not more commonly on display?

Joe: It’s unavoidable that as ideas spread, they get misinterpreted and misapplied, but I think there are a few things going on. First, the issue is deeper than people first realize. Grading is much more complex than it seems at first blush, implicating fields of pedagogy, adolescent development, and concepts of statistical validity. But in order to fully explain the complexity, I’ll have to expand on that in another post.

Second, sometimes we who advocate or implement equitable grading don’t explain ourselves enough to skeptical observers. Many well-meaning district and school administrators can make the mistake of quickly enacting equitable grading policies without meaningfully engaging and educating their teachers or student and parent communities. In order for equitable grading to work, we have to explain the theory and research—including teachers’ classroom-based evidence—demonstrating both the harms and inaccuracies of traditional grading practices as well as the benefits of equitable grading practices, and then provide teachers the support to implement them effectively.

But it’s also about how people receive these ideas. Changes to grading can elicit strong concerns and emotions, and the word “equity” itself is so charged right now that it’s easy to make assumptions about equitable grading before it’s understood. Every time I speak with educators, parents, or students, I realize that while grading and equity are both hot topics, we’re not used to talking about the deep complexities of either. So if we’re ever going to understand their intersection, then we’re obligated to approach equitable grading with curiosity and to make sure we don’t propagate misunderstandings or half-understandings.

Rick: That’s all fair enough. But a lot of the practices I’ve seen presented as “equitable grading”—by prominent advocates and big school systems—don’t seem to reflect your commitment to honesty-for-all. I’m thinking of policies that offer endless retakes or put an end to graded homework. I’ve had plenty of educators quietly complain to me that this stuff is a recipe for lowering expectations, permitting students to coast, and making diligent students feel like suckers. Am I getting this wrong? What do you think of these practices?

Joe: You cite perfect examples of where equitable grading ideas have gotten warped by superficial understanding or overzealous policymakers. Let’s take your example of “endless retakes,” which I have a hunch is hyperbolic shorthand. When we grade equitably, we offer students the opportunity to learn from their mistakes. If we agree that the principle of a retake or redo is a good one, then teachers need to figure out the most effective answers to a series of challenging questions: How can we create and implement retakes efficiently? What is necessary before a student gets a retake? When can they be administered and by whom? When is it time to move on? How can we make sure that the retake grade doesn’t have a “ceiling” score or that we don’t average a student’s scores—both of which would misrepresent their current and accurate understanding and would punish students who struggled but ultimately demonstrated understanding?

Another example: With equitable grading, a student’s homework performance isn’t included in their grade calculation, and therefore some misconstrue equitable grading as de-valuing homework. On the contrary, meaningful homework can serve a vital role in learning: practice. Teachers should give feedback on homework and even record a student’s work in the gradebook, but if we agree that homework is the opportunity for students to practice and make mistakes, then we undermine those purposes if we include their performance on that homework in the grade calculation. No one would argue that a runner’s time in a race should incorporate their practice times, so why would we believe our grades are accurate and fair when we include students’ performance during their practice?

There’s no coasting in equitable grading. In fact, teachers tell us—and students complain but appreciate—that equitable grading raises expectations. Rather than take a test and be done with it, equitable grading normalizes subsequent learning through additional practice. In traditional grading, whether students learn from homework is irrelevant so long as it’s completed—regardless of whether it was completed by the student, their tutor, or the internet. In equitable grading, successful learning depends on students learning from their homework. After all, no one counts the free throws you make during practice and adds that score to the game score. But if you don’t practice free throws, you won’t make them during the game. That means that teachers need to help students understand the value of homework by having clear ties between what’s on the homework and what’s on the test and to incorporate consequences for not doing homework that aren’t grade-based, like requiring extra time or providing supports.

Rick: OK. Love the point about not getting extra points for practice performance. While I wouldn’t say I’m convinced, I’m certainly a whole lot more sympathetic to what you’re talking about than to what I’ve generally encountered as “equitable grading.” But I think that’s partly because what you’re describing sounds like it could just as easily be tagged “honest grading” or “rigorous grading.” Given that, I’m just curious: Why call it “equitable grading”?

Joe: You’re not the first to suggest that I should call this something else, like “common-sense grading” or “accurate grading” or “fair grading” to avoid the political radioactivity of “equitable grading.” But I believe it’s important to call it what it is—improvements to traditional grading with an explicit awareness of the history of grading, and schooling, in this country—and to correct ways in which our traditional grading practices disproportionately benefit or harm groups of students.

Interestingly, people can mistakenly assume that it’s the historically underserved students who are the primary recipients of grade inflation. In fact, research and my organization’s experiences working with teachers suggest that grade inflation and false reporting of student achievement occurs just as frequently—and leads to a greater number of inaccurate A’s—among students who have more supports, whose families are of higher income, and who attend higher-performing schools. In these circumstances, grade inflation is not generally a result of empathy, but is instead fueled by a version of Ted Sizer’s famed Horace’s Compromise : Powerful parents support a school—and possibly pay expensive tuition—with the expectation that their child will receive high grades and be maximally competitive for admission to the most selective colleges. The good news is that while teachers may have little influence to counteract the intense pressures of families, they have nearly complete authority to improve their grading in order to correct the harms of traditional grading and to align the best teaching with the best grading.

Another example: In most classrooms, teachers include in a grade not only a student’s performance on assessments—what a student knows —but also whether a student completed homework, came to class on time, raised their hand in a discussion, brought in a signed syllabus, and everything and anything else that happens in a classroom; in other words, what a student does . The result of this incorporation of both academic and nonacademic criteria into a grade—what Robert Marzano has called “omnibus grading”—is that the accuracy of grades becomes compromised, and it’s unclear what a grade represents: The student who showed A-level understanding on an assessment but handed it in late receives a B, while the student who showed B-level understanding on the assessment but completed an unrelated extra-credit assignment receives an A. Now, imagine the complex formulas in many teachers’ gradebooks—30 percent tests, 25 percent homework, 25 percent participation, 15 percent group work, and 5 percent extra credit—and the dozens of entries in the categories, and grades become a stew of so many diverse inputs of student performance that in the quest to mean everything a grade means nothing and introduces both inaccuracy and confusion. Teachers can make grades more accurate by reducing the “noise” of data so the grade is simply, and entirely, a description of a student’s understanding of course content.

Rick: So, let me see if I have this right. While I’ve generally found equitable grading presented as measures that seem calculated to lessen rigor and “decenter” traditional academic norms, you’re telling me that it should be about ensuring a rigorous, consistent bar for all students?

Joe: Exactly. In fact, it has implications that are surprising to some. While most talk of equitable grading focuses on low-income students and children of color, including behavior and nonacademic criteria in grades tends to inflate the grades of students who have the most resources and are best able to accommodate, adhere to, and comply with a teacher’s expected behaviors. The student who has a stay-at-home parent, higher income, greater fluency in English, and more academic support—perhaps a tutor—is more likely to earn all the points from the nonacademic “assignments” of getting to class on time, completing every homework assignment correctly, contributing to every discussion, and satisfying every extra-credit opportunity, whether points are awarded for bringing in tissues for the classroom or a ticket receipt from a local museum exhibit. In this way, if a student has less understanding of content, but can compensate for that deficiency by satisfying other categories, then their grade will be inflated. In several studies, including Fordham’s 2018 Report on Grade Inflation , grade inflation was more pronounced at schools with fewer students from low-income families. Plus, when students’ nonacademic behavior—categories such as “participation” or “effort”—are included in the grade, teachers award points to students have particular personality types: those “who appear attentive and aggressive during class and who therefore receive higher grades than others, not because they have learned more material but because they have learned to act like they are learning more.” I’m sure we agree that a student’s personality type can’t be accurately assessed and certainly shouldn’t be included in the grade.

We can make our grades more accurate and fair for all students by excluding nonacademic criteria, dampening subjective biases, and reducing the impact of resource disparities.

Rick: All right, my friend. You’ve got me interested. I’m not confident that schools can do this responsibly. And I’m concerned that the zeitgeist around “equitable grading” is so far from what you—the author of the go-to book!—has to say. But let’s get into all that at greater length. If you’re game, we’ll dig into all this further.

Joe: Absolutely!

The opinions expressed in Rick Hess Straight Up are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

10 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Exploring the benefits of a no-homework policy, this article delves into the traditional perspective that homework is fundamental for reinforcing classroom lessons, instilling discipline, and fostering student responsibility. Yet, a burgeoning amount of research challenges this notion, suggesting that abolishing homework could significantly augment academic outcomes and student well-being. Within the context of innovative student council ideas , we will outline ten persuasive arguments for schools to adopt a no-homework policy, underscoring the comprehensive advantages of this strategy. These benefits include promoting independent learning, equalizing educational opportunities, encouraging creative thinking, and improving physical health. By considering a shift towards no homework, educational institutions can potentially transform the learning experience, making it more effective, enjoyable, and equitable for all students.

For those seeking additional support, services like WritePaper provide a platform for students to receive assistance with their writing tasks, further alleviating the pressures of traditional homework assignments.

Enhanced Family Time

The benefits of no homework start with enriched family interactions. Without the burden of homework, students have more time to spend with family, fostering stronger bonds and allowing for valuable life lessons that aren’t taught in classrooms. This quality time can significantly improve communication within the family, helping parents and children understand each other better. It also allows parents to share their knowledge and experiences, offering a different perspective on life and learning. Furthermore, family time can help relieve the stress and pressure of school, creating a more balanced and nurturing environment for children to grow.

Increased Extracurricular Engagement

A no-homework policy opens up opportunities for students to explore extracurricular activities. Whether it’s sports, arts, or community service, engaging in these activities can lead to a well-rounded education, promoting teamwork, leadership, and time management skills. Such involvement enriches students’ educational experience and helps them discover new passions and talents. Moreover, extracurricular activities provide practical experiences that build character and prepare students for the challenges of the real world. They encourage students to set goals, work towards them, and celebrate their achievements, fostering a sense of accomplishment and self-worth that transcends academic success.

Reduced Stress and Burnout

One of the most significant benefits of having no homework is reducing stress and burnout among students. Excessive homework can lead to sleep deprivation, anxiety, and depression. By removing this stressor, students can maintain better mental health and improve their overall quality of life. This alleviation of stress enhances academic performance and contributes to more positive social interactions and increased participation in class. It allows students to approach their studies with a refreshed mind and a more focused attitude, ultimately leading to a deeper and more meaningful engagement with their education. Furthermore, a healthier state of mind enables students to tackle challenges with resilience and adaptability, essential for success inside and outside the classroom.

Encourages Independent Learning

Contrary to the belief that homework is necessary for reinforcing learning, a no-homework policy can encourage students to pursue knowledge independently, fostering a love for learning that is self-directed and driven by curiosity rather than obligation. This approach empowers students to take charge of their education, seeking information and resources that interest them. It nurtures critical thinking and research skills as students learn to question, analyze, and synthesize information from various sources. Moreover, independent learning encourages students to set academic goals and develop strategies to achieve them, instilling a sense of responsibility and self-motivation. This autonomy in learning prepares students for the demands of higher education and a lifelong journey of personal and professional growth.

Improved Sleep

Numerous studies link excessive homework to sleep deprivation. With no homework benefits, including more rest, students can improve their concentration, memory, and learning ability, leading to better academic performance.

More Time for Personal Development

The benefits of no homework extend to personal development. Students have more time to explore personal interests, develop hobbies, and engage in activities contributing to their identity and self-esteem.

Better Classroom Engagement

Without the fatigue and stress of homework, students are likelier to be engaged and participative in class. This creates a more vibrant learning environment where students feel motivated to contribute.

Equalizes Educational Opportunities

Why students should not have homework: This stance argues for eliminating homework to foster equity and equal educational opportunities. Homework disproportionately impacts students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, as they may lack access to essential resources or a conducive study environment at home. A no-homework policy can level the playing field, giving all students a fair chance to succeed academically. Such a policy acknowledges the diverse home environments and resource availability, aiming to reduce educational disparities and support inclusive learning for every student.

Encourages Creative Thinking

Why students should not have homework: The benefits of not having homework include encouraging creative thinking. By eliminating homework, students gain more free time, enabling them to delve into creative pursuits and exercise critical thinking beyond structured academic tasks. This newfound freedom can spark innovative ideas and solutions, nurturing invaluable creativity skills essential in academic environments and real-world scenarios. By prioritizing creative exploration, students develop a more well-rounded intellect and problem-solving abilities, preparing them for future challenges.

Healthier Lifestyles

Finally, the benefits of no homework include promoting healthier lifestyles. With extra time, students can engage in physical activities, pursue interests that contribute to their physical well-being, and balance work and leisure, leading to healthier, happier lives.

While homework has traditionally been viewed as an essential component of education, the benefits of no homework present a compelling case for reevaluating its role in how to get good grades in middle school . By fostering family time, reducing stress, encouraging independent learning, and promoting a healthier lifestyle, a no-homework policy can significantly enhance students’ educational experience and well-being. As educators and policymakers reflect on these benefits and how they contribute to achieving good grades in middle school, it’s crucial to consider innovative approaches to learning that prioritize student well-being and holistic development over traditional homework assignments.

Related Posts

Best online jobs for college students.

- March 26, 2024

How to Earn Money as a College Student

- March 20, 2024

How to Be a Good College Student: A Comprehensive Guide

- March 12, 2024

How to Get Good Grades in Middle School

Grading for Equity

- Posted December 11, 2019

- By Jill Anderson

When Joe Feldman, Ed.M.'93, author of Grading for Equity , looked closer at grading practices in schools across the country, he realized many practices are outdated, inconsistent, and inequitable. Today he helps educators develop strategies that tackle inconsistent grading practices. In this episode of the Harvard EdCast, Feldman discussed how shifting grading practices can change the landscape of schools and potentially the future for students.

Jill Anderson: I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast. Joe Feldman believes how teachers grade students today is often outdated, inconsistent and inequitable. He's a former educator who's been examining grading practices, and believes there's better ways to do it. He's been working with schools to develop strategies that reimagine how we grade students. Some of these strategies go beyond common practices like using extra credit, to really assessing how well a student is mastering the content. When I spoke with Joe, I asked him why grading hasn't changed very much?

Most teachers have never really had an opportunity to think very critically about grading. It's not part of our credentialing work, it's not part of our professional development often. Even when we're given some new curriculum or new instructional strategies, grading is really pushed outside the conversation. Most people think it exists almost outside teaching, and that it's just this sort of calculation, this sort of bean counting, but it's actually interwoven into every pedagogical decision that teachers make, because whenever they make a choice about an activity, or some work, or some assessment, they have to decide whether or not to grade it. And if so, with what weight? With what consequences? All kinds of things like that.

We really are using an inherited grading structures and practices that date back to the industrial revolution, when we had different ideas about what schools were for, and what learning should look like, and what we believed about kids, and which kids we believe those things, and which kids we sort of dismissed.

Because there hasn't been a lot of good research and attention to grading, we've just been replicating how we were taught. You know, we'd say, well, it seems like a good idea to drop the lowest grade if kids have done all their homework. That seems like a reasonable thing to do. And we just are all kind of winging it, or doing it based on what our mentor teacher did, or our department may have shared an idea, but we just haven't had the opportunity to critically examine it. I hope that the work that I'm doing gives teachers and schools a license, and vocabulary, and a space to start to really interrogate the grading practices that we use.

Jill Anderson: I mean, I was struck by how inconsistent grading can be across the same school. Why do you think that inconsistency is so problematic?

Joe Feldman: If you look at it from the viewpoint of the student, so in a typical day in middle school or high school, students are seeing five, six, even more teachers each day. Every teacher is usually doing their own approaches to grading, and many of them become idiosyncratic. Although every teacher has deep beliefs that they're trying to imbue in their grading, and send certain messages and values to students, and trying to build a certain kind of learning community, every teacher is doing it differently. From the student, it adds to my cognitive load. I not only have to understand the content and try and perform at high levels of the content, but now I also have to navigate a grading structure that may not be totally transparent, and may be different for every teacher, and particularly for students who are historically underserved and have less education background, and fewer resources and sort of understanding of how to navigate those really foreign systems to a lot of our students, it places those additional burdens on them, which we shouldn't do.

Jill Anderson: Talk to me a little bit about this idea of inequity and grading.

Joe Feldman: When I first started doing this work, I had been a teacher for years, and a principal of a couple of different high schools, and worked as a district administrator in New York city, and in Northern California as a director of curriculum and instruction, supervised principals and coach teachers. Through all of that work, grading had always nagged at me because there was no way to address these inconsistencies. I began interviewing more teachers and principals, and everyone was frustrated with grading. As I did more research, I found that the traditional practices that we use actually perpetuate disparities that have been going on for years by race, income, education, background, language. The frustrating part I think, is that so many of us go into education to try and disrupt and counteract these cycles of disparities over generations, and do great work and thinking about culturally responsive pedagogy and diverse curriculum, and really trying to listen to our students, and yet we are using practices that undermine those things and actually work against all of the great equity work that we've been doing.

Jill Anderson: Can you tell me some of the strategies that you propose for changing grading in schools?

Joe Feldman: I'll start with talking about a common practice that perpetuates inequities and what to do instead. One example is the traditional idea that we average a student's performance over time. And actually grade book software does this by default. If you imagine students do some homework, and then they do a quiz or two, and then there's some summit of assessment or test at the end of some unit.

The way that we traditionally grade those things is that we assign point values for all those things, and students score a certain number of them out of a certain number of possible. Then we add up all those numbers and divide the number earned by the number possible. What that is doing is it's averaging all of the performances together into a single grade.

The problem with that, is that for the student who does well from the very beginning and gets A's on everything, their performance is fine, their average is an A, but for the student who struggles at the beginning and gets very low grades, D's and C's and even F's as they are in the process of learning, and even on early quizzes when they demonstrate mastery on the test and let's say they get an A on the test, because they have those earlier grades that ostensibly were for assignments and assessments that were on the path to learning, that they were supposed to learn from, and that they weren't even supposed to have learned everything yet, when we include those early scores, it pulls down the final grades, so it actually misrepresents the level of mastery that a student has ultimately demonstrated.

The reason why that's so inequitable, is that for the student who, before coming to class, attended summer workshops or had parents who gave them a much richer educational environment because they had the time, and the education, and the money, or the students who had a great teacher the year before, they're going to come in at the beginning of that unit and do much better, and the student who hasn't had those resources and privileges is going to start lower. When you average a student's performance over time, you are actually perpetuating those disparities that occurred before that student came into your class. The alternative then, is that you wouldn't include earlier performances. You would only include in the grade how a student did at the end of their learning, not to include the mistakes they made in the process.

Jill Anderson: Do you see that as the biggest change a school or teachers could make in the process of grading?

Joe Feldman: It's only one of, like a dozen. That's just one example, and that really is just about how you calculate the grade. What's hard about that for teachers to get their head around, is that that's all they've ever known is, I put the numbers into my software, and the software does the calculation, and then poof, out comes a number. What I try and get teachers to recognize and own, is that if they allow the software to do that, that is an affirmative decision that they're making, that averaging a student's performance is the most accurate and equitable way to describe that student, and it's not. Just helping them recognize that they have a choice in how grades are calculated, is a huge step toward really empowering teachers and giving them a greater sense of ownership and responsibility over how they grade. But there are many other practices.

Jill Anderson: Right. Some of the things I was reading about, doing away with extra credit, making homework not something that counts toward the final grade, and really reevaluating how teachers look at class participation, all these sort of extras that usually play into a student's grade. Can you talk a little bit more about some of those items, because that's big, to do away with some of that stuff, or look at it completely differently?

Joe Feldman: Yeah, and I think what you sense, is that this can be very disorienting to teachers and cause a lot of disequilibrium, because it is helping them see that the practices that they believed were right may actually be hurting students and giving inaccurate information. This is often very difficult and exciting work for teachers.

One category is to not include a student's behavior in their grade. In many classrooms, teachers use grades as a classroom management strategy, and as a way to incentivize students to do behaviors that the teachers believe will support learning. An example is, in middle school we want to teach students that they need to bring their materials every day. What we will do is we will give them five points, up to five points each day if they bring their notebook, their pen, their calculator, et cetera. Teachers do this, because they believe that those kinds of skills are really important for students to be academically successful. The teachers are absolutely right that those skills are critical.

The problem is that when you include student behaviors in the grade, you start to misrepresent and warp the accuracy. An example is a student every day brings their notebook and pen and they get five points every day, but they do poorly on the quiz or the test. What happens is, is even though they may have gotten a C or a D on the test, because they brought the materials every day, or because they've raised their hand and asked a question every day, or because they are respectful, or turn things in on time, they're getting all these points that are then lifting that C test grade to a B or even an A minus.

The big problem with that, well, there are several, one of which is that you're miscommunicating to the student where they are. You're telling the student that they're at a B level in your content, and they're actually at a C. So they don't think there's a problem, the counselors don't think there's a problem, the parents don't think it's a problem, and the student goes to the next grade level and gets crushed by the content, because they have no idea that they weren't prepared for the rigor of that class because they kept getting the message that they were getting B's.

A second big problem with including behavior in the grade for things like participation, is that often the way that teachers interpret student behaviors are through a culturally specific lens. Like whose norms are the teachers applying when they are grading students on their participation? We have to recognize that students learn in a variety of ways, many of which are not the ways that we learn. Just because a student isn't taking notes doesn't mean that they're not learning. And conversely, just because a student is taking notes doesn't mean they're learning. What we are doing is that we are grading a student on acting as if they are learning. They are going through the motions of learning, whether or not they actually learned or not, and we're rewarding or punishing them. The only way to know whether a student has actually learned is to assess them, not to examine and try and subjectively evaluate a behavior. That's sort of one category.

The other is around homework. First of all, I want to clarify, it's not that homework is optional. Homework should still be required and expected, but it's just we wouldn't include the student's performance in their grade. The way I like to think about equitable grading is that we want it to have three pillars. The first is that the grades are accurately describing a student's academic performance. The second is that the grade is bias resistance, so it counteracts institutional biases and protects grades from being infected by our implicit biases, so institutional and implicit biases. Thirdly, we want it to be motivational, to build student's intrinsic motivation, not extrinsic.

All right, so I'm going to walk through homework, and talk about why our traditional use of incorporating a student's performance on homework and their grade violate each of these. The first is around accuracy, so we don't know who did the student's homework, frankly. Many students particularly, well actually across all spectrums, they copy, as part of the partnerships I have with schools when we do this work is I interview students, and I have never had a student tell me that they have not copied homework. It happens and when I ask them why, they say, well, if I don't know how to do something, I need help, or I forget and I need help. The bottom line is if I don't do this, I won't get the points. Students are copying other people's homework. When we include a student's performance on homework in the grade, we may be including other students, or tutors, or parents performance in a grade. We just never know. So it challenges the accuracy.

It also does what I mentioned before. Many teachers will say, well, I don't want to grade the homework for accuracy. I'll grade it for completion. Just if the kid tried, I don't care if they got answers wrong. Then what you're doing is the same thing I mentioned earlier, which is if a student doesn't know the answers on the homework but they try every day and they don't know it on the test, then all those completed homework assignments that gave them five points for each one is going to inflate the test grade. So you're going to again, warp the accuracy.

Okay, so bias resistance. Well, we know that homework is often a filter for privilege, that students who have resources at home, whether they be internet access, or caregivers who have a college education or who have time to help them, settings that have a quiet space to do work, students who don't have other responsibilities like taking care of siblings or having jobs, those students are more likely to complete homework compared to the students who don't have those resources. When we include a student's performance on homework in the grade, we are rewarding students who have those resources and punishing those who don't.

The third part is around motivation, the third pillar is motivation. The reason we assign homework in the first place is because students need practice. If they do this practice, they will then be able to perform on the test, and we actually want them to make mistakes on homework, because if there's any place that you should make mistakes in your learning, you should do it when you're practicing like on homework. If we say to students, you should make mistakes on homework, that's where you should make them, and we include their performance on that homework in the grade we're telling them make a lot of mistakes and we're going to punish you for it, which is totally confusing and undermines our messaging.

We also have to recognize that students understand the relationship between practice for no points or no reward, and then being able to perform later for the reward. If I go out and shoot free throws for two hours because I'm practicing, I know that I'm not getting any points for that, it's that I do those practices so that when I get to the game I can make the points. Students understand it on video games, I go to these sandbox areas and I'm just playing and practicing and making a lot of mistakes and I'm not getting any points, but I do it so that when I go and fight the boss monster, I can beat the boss monster, right? They understand means and ends of practice perform. Every student in performing arts get to too.

But we in our traditional thinking about grading have detached the purpose of homework from its outcome. So we say don't do homework for you, do it for me, because I'm the teacher, I'm going to give you points for doing it, and then later you'll be able to do well on the test. Instead we can reconnect the relationship and say, the reason you do homework is not for me, you do it for you, because when you do the practice, you do better on the performance.

Teachers initially are very worried about this and say, oh, I don't give students points for homework, they won't do it. Sometimes that happens, and there's an initial dip, but then teachers start spending time helping students see the relationship between the homework and the tests. They will give them a quiz, and if students don't do well on it, they will say, well, let's look at which homework you did and, oh, I'm going to put up a little chart on the board that shows that of the students who did the three homework preceding the quiz, their average grade was a B plus or A minus, and the students who didn't do it, their average grade was a D. What do you think is going on students? Then they can even say to students, let's look at the quiz and look for where there were examples in the homework that showed up on the quiz, right. Helping students recognize the connection between the two.

What teachers find is that students then do their homework for no points, because students have internalized the relationship between the homework and the test, and teachers are shocked that students do homework and they cannot believe that they had for years and years been essentially managing students' behaviors and rewarding them little chits for doing what they asked. And frankly, it's a much more empowering and 21st century skill to recognize when I need to practice something, and only do the amount of homework that I need so that I'm ready for when the test comes, because after all in post secondary education and in the professional world, nobody is giving you any value for the work you do outside of class. It's all up to you to decide how much you need.

Jill Anderson: I mean, you hit on something about teachers struggle with these changes a lot. Why do you think grading is such a sensitive topic for teachers?

Joe Feldman: It's funny. When I was a principal, grading was the most difficult conversation to have with a teacher. Administrators I talked to all over, whether they be at the elementary, middle, or high school, or district level, they're all frustrated with how grading is addressed, and the inconsistency and the problems that that generates. But it's so difficult for them to broach the subject. I think what it's about is that especially today, there are so many demands placed on teachers, and expectations and mandates from multiple layers, right? The school districts, state, federal and all kinds of roles they have to serve. I think grading is really the last island of autonomy that teachers have. That it is the one place where they can bring their full professional judgment and expertise in a formalized way, and in a way that perseveres and stays with students. I mean, it is the sort of the kind of core of their power, for many teachers their identity.

When people start to push against that, it can be very hard for teachers to hear it, and teachers justifiably get very defensive oftentimes. You know, when a principal comes up and says to a teacher, I'd like to talk to you about grading, the teacher's reaction is not, oh, let's have a good intellectual discussion. It's what teacher called you? Or what parent called you? Or what grade do you want me to change? Or that kind of thing. The way that I encourage principals, school leaders, and district leaders to do this work, is to create areas for teachers to explore the practices on their own. Not to come in and say to teachers, hey, you know what? Starting next year we're not going to include homework in the grade anymore. It's too jarring, too much of a power play for the school leader. Instead, there have to be ways that teachers can explore and better understand these practices themselves because when they start trying them, they find great results.