- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Humanity often pays a high price for progress and understanding — at least, that seems to be the case in many famous psychological experiments. Human experimentation is a very interesting topic in the world of human psychology. While some famous experiments in psychology have left test subjects temporarily distressed, others have left their participants with life-long psychological issues . In either case, it’s easy to ask the question: “What’s ethical when it comes to science?” Then there are the experiments that involve children, animals, and test subjects who are unaware they’re being experimented on. How far is too far, if the result means a better understanding of the human mind and behavior ? We think we’ve found 20 answers to that question with our list of the most unethical experiments in psychology .

Emma Eckstein

Electroshock Therapy on Children

Operation Midnight Climax

The Monster Study

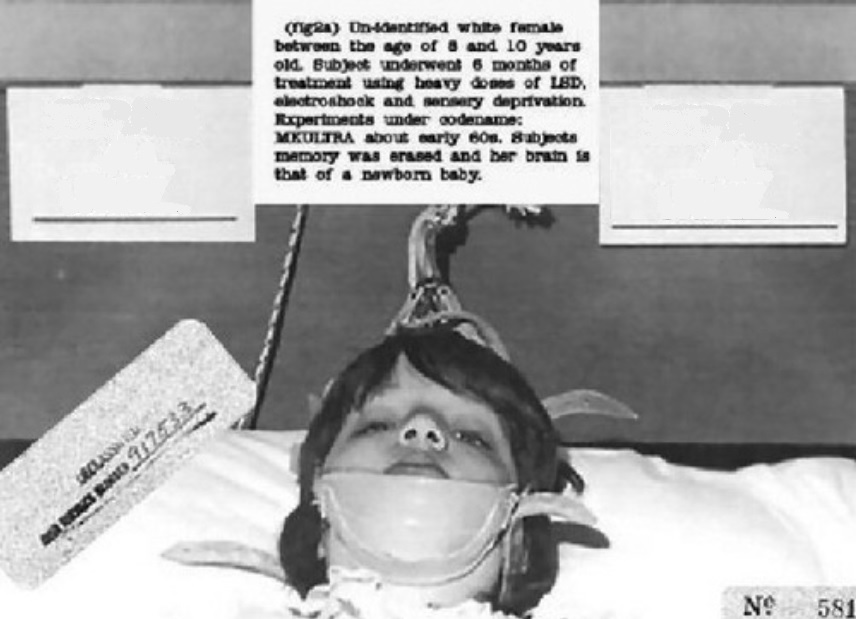

Project MKUltra

The Aversion Project

Unnecessary Sexual Reassignment

Stanford Prison Experiment

Milgram Experiment

The Monkey Drug Trials

Featured Programs

Facial expressions experiment.

Little Albert

Bobo Doll Experiment

The Pit of Despair

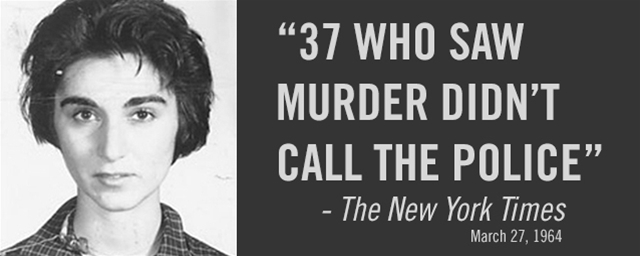

The Bystander Effect

Learned Helplessness Experiment

Racism Among Elementary School Students

UCLA Schizophrenia Experiments

The Good Samaritan Experiment

Robbers Cave Experiment

Related Resources:

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- What is Experimental Psychology?

- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Research ethics.

Jennifer M. Barrow ; Grace D. Brannan ; Paras B. Khandhar .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Multiple examples of unethical research studies conducted in the past throughout the world have cast a significant historical shadow on research involving human subjects. Examples include the Tuskegee Syphilis Study from 1932 to 1972, Nazi medical experimentation in the 1930s and 1940s, and research conducted at the Willowbrook State School in the 1950s and 1960s. [1] As the aftermath of these practices, wherein uninformed and unaware patients were exposed to disease or subject to other unproven treatments, became known, the need for rules governing the design and implementation of human-subject research protocols became very evident.

The first such ethical code for research was the Nuremberg Code, arising in the aftermath of Nazi research atrocities brought to light in the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials. [1] This set of international research standards sought to prevent gross research misconduct and abuse of vulnerable and unwitting research subjects by establishing specific human subject protective factors. A direct descendant of this code was drafted in 1978 in the United States, known as the Belmont Report, and this legislation forms the backbone of regulation of clinical research in the USA since its adoption. [2] The Belmont Report contains 3 basic ethical principles:

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

Additionally, the Belmont Report details research-based protective applications for informed consent, risk/benefit assessment, and participant selection. [3]

- Issues of Concern

The first protective principle stemming from the 1978 Belmont Report is the principle of Respect for Persons, also known as human dignity. [2] This dictates researchers must work to protect research participants' autonomy while also ensuring full disclosure of factors surrounding the study, including potential harms and benefits. According to the Belmont Report, "an autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and acting under the direction of such deliberation." [1]

To ensure participants have the autonomous right to self-determination, researchers must ensure that potential participants understand that they have the right to decide whether or not to participate in research studies voluntarily and that declining to participate in any research does not affect in any way their access to current or subsequent care. Also, self-determined participants must be able to ask the researcher questions and comprehend the questions asked by the researcher. Researchers must also inform participants that they may stop participating in the study without fear of penalty. [4] As noted in the Belmont Report definition above, not all individuals can be autonomous concerning research participation. Whether because of the individual's developmental level or because of various illnesses or disabilities, some individuals require special research protections that may involve exclusion from research activities that can cause potential harm or appointing a third-party guardian to oversee the participation of such vulnerable persons. [5]

Researchers must also ensure they do not coerce potential participants into agreeing to participate in studies. Coercion refers to threats of penalty, whether implied or explicit, if participants decline to participate or opt out of a study. Additionally, giving potential participants extreme rewards for agreeing to participate can be a form of coercion. The rewards may provide an enticing enough incentive that the participant feels they need to participate. In contrast, they would otherwise have declined if such a reward were not offered. While researchers often use various rewards and incentives in studies, they must carefully review this possibility of coercion. Some incentives may pressure potential participants into joining a study, thereby stripping participants of complete self-determination. [3]

An additional aspect of respecting potential participants' self-determination is to ensure that researchers have fully disclosed information about the study and explained the voluntary nature of participation (including the right to refuse without repercussion) and possible benefits and risks related to study participation. A potential participant cannot make a truly informed decision without complete information. This aspect of the Belmont Report can be troublesome for some researchers based on their study designs and research questions. Noted biases related to reactivity may occur when study participants know the exact guiding research questions and purposes. Some researchers may avoid reactivity biases using covert data collection methods or masking critical study information. Masking frequently occurs in pharmaceutical trials with placebos because knowledge of placebo receipt can affect study outcomes. However, masking and concealed data collection methods may not fully respect participants' rights to autonomy and the associated informed consent process. Any researcher considering hidden data collection or masking of some research information from participants must present their plans to an Institutional Review Board (IRB) for oversight, as well as explain the potential masking to prospective patients in the consent process (ie, explaining to potential participants in a medication trial that they are randomly assigned either the medication or a placebo). The IRB determines if studies warrant concealed data collection or masking methods in light of the research design, methods, and study-specific protections. [6]

The second Belmont Report principle is the principle of beneficence. Beneficence refers to acting in such a way to benefit others while promoting their welfare and safety. [7] Although not explicitly mentioned by name, the biomedical ethical principle of nonmaleficence (not harm) also appears within the Belmont Report's section on beneficence. The beneficence principle includes 2 specific research aspects:

- Participants' right to freedom from harm and discomfort

- Participants' rights to protection from exploitation [8]

Before seeking IRB approval and conducting a study, researchers must analyze potential risks and benefits to research participants. Examples of possible participant risks include physical harm, loss of privacy, unforeseen side effects, emotional distress or embarrassment, monetary costs, physical discomfort, and loss of time. Possible benefits include access to a potentially valuable intervention, increased understanding of a medical condition, and satisfaction with helping others with similar issues. [8] These potential risks and benefits should explicitly appear in the written informed consent document used in the study. Researchers must implement specific protections to minimize discomfort and harm to align with the principle of beneficence. Under the principle of beneficence, researchers must also protect participants from exploitation. Any information provided by participants through their study involvement must be protected.

The final principle contained in the Belmont Report is the principle of justice, which pertains to participants' right to fair treatment and right to privacy. The selection of the types of participants desired for a research study should be guided by research questions and requirements not to exclude any group and to be as representative of the overall target population as possible. Researchers and IRBs must scrutinize the selection of research participants to determine whether researchers are systematically selecting some groups (eg, participants receiving public financial assistance, specific ethnic and racial minorities, or institutionalized) because of their vulnerability or ease of access. The right to fair treatment also relates to researchers treating those who refuse to participate in a study fairly without prejudice. [3]

The right to privacy also falls under the Belmont Report's principle of justice. Researchers must keep any shared information in their strictest confidence. Upholding the right to privacy often involves procedures for anonymity or confidentiality. For participants' data to be completely anonymous, the researcher cannot have the ability to connect the participants to their data. The study is no longer anonymous if researchers can make participant-data connections, even if they use codes or pseudonyms instead of personal identifiers. Instead, researchers are providing participant confidentiality. Various methods can help researchers assure confidentiality, including locking any participant identifying data and substituting code numbers instead of names, with a correlation key available only to a safety or oversight functionary in an emergency but not readily available to researchers. [3]

- Clinical Significance

One of the most common safeguards for the ethical conduct of research involves using external reviewers, such as an Institutional Review Board (IRB). Researchers seeking to begin a study must submit a full research proposal to the IRB, which includes specific data collection instruments, research advertisements, and informed consent documentation. The IRB may perform a complete or expedited review depending on the nature of the study and the risks involved. Researchers cannot contact potential participants or start collecting data until they obtain full IRB approval. Sometimes, multi-site studies require approvals from several IRBs, which may have different forms and review processes. [3]

A significant study aspect of interest to IRB members is using participants from vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups may include individuals who cannot give fully informed consent or those individuals who may be at elevated risk of unplanned side effects. Examples of vulnerable participants include pregnant women, children younger than the age of consent, terminally ill individuals, institutionalized individuals, and those with mental or emotional disabilities. In the case of minors, assent is also an element that must be addressed per Subpart D of the Code of Federal Regulations, 45 CFR 46.402, which defines consent as "a child's affirmative agreement to participate in research; mere failure to object should not, absent affirmative agreement, be construed as assent." [9] There is a lack in the literature on when minors can understand research, although current research suggests that the age by which a minor could assent is around 14. [10] Anytime researchers include vulnerable groups in their studies, they must have extra safeguards to uphold the Belmont Report's ethical principles, especially beneficence. [3]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Research ethics is a foundational principle of modern medical research across all disciplines. The overarching body, the IRB, is intentionally comprised of experts across various disciplines, including ethicists, social workers, physicians, nurses, other scientific researchers, counselors, mental health professionals, and advocates for vulnerable subjects. There is also often a legal expert on the panel or available to discuss any questions regarding the legality or ramifications of studies.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Jennifer Barrow declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Grace Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Paras Khandhar declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Barrow JM, Brannan GD, Khandhar PB. Research Ethics. [Updated 2022 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- The historical, ethical, and legal background of human-subjects research. [Respir Care. 2008] The historical, ethical, and legal background of human-subjects research. Rice TW. Respir Care. 2008 Oct; 53(10):1325-9.

- The Belmont Report at 40: Reckoning With Time. [Am J Public Health. 2018] The Belmont Report at 40: Reckoning With Time. Adashi EY, Walters LB, Menikoff JA. Am J Public Health. 2018 Oct; 108(10):1345-1348. Epub 2018 Aug 23.

- Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg code. [BMJ. 1996] Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg code. Vollmann J, Winau R. BMJ. 1996 Dec 7; 313(7070):1445-9.

- Review The History of Human Subjects Research and Rationale for Institutional Review Board Oversight. [Nutr Clin Pract. 2021] Review The History of Human Subjects Research and Rationale for Institutional Review Board Oversight. Spellecy R, Busse K. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021 Jun; 36(3):560-567. Epub 2021 Jan 13.

- Review Ethical issues in research. [Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gyn...] Review Ethical issues in research. Artal R, Rubenfeld S. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017 Aug; 43:107-114. Epub 2017 Jan 23.

Recent Activity

- Research Ethics - StatPearls Research Ethics - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

5 Unethical Medical Experiments Brought Out of the Shadows of History

Prisoners and other vulnerable populations often bore the brunt of unethical medical experimentation..

Most people are aware of some of the heinous medical experiments of the past that violated human rights. Participation in these studies was either forced or coerced under false pretenses. Some of the most notorious examples include the experiments by the Nazis, the Tuskegee syphilis study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the CIA’s LSD studies.

But there are many other lesser-known experiments on vulnerable populations that have flown under the radar. Study subjects often didn’t — or couldn’t — give consent. Sometimes they were lured into participating with a promise of improved health or a small amount of compensation. Other times, details about the experiment were disclosed but the extent of risks involved weren’t.

This perhaps isn’t surprising, as doctors who conducted these experiments were representative of prevailing attitudes at the time of their work. But unfortunately, even after informed consent was introduced in the 1950s , disregard for the rights of certain populations continued. Some of these researchers’ work did result in scientific advances — but they came at the expense of harmful and painful procedures on unknowing subjects.

Here are five medical experiments of the past that you probably haven’t heard about. They illustrate just how far the ethical and legal guidepost, which emphasizes respect for human dignity above all else, has moved.

The Prison Doctor Who Did Testicular Transplants

From 1913 to 1951, eugenicist Leo Stanley was the chief surgeon at San Quentin State Prison, California’s oldest correctional institution. After performing vasectomies on prisoners, whom he recruited through promises of improved health and vigor, Stanley turned his attention to the emerging field of endocrinology, which involves the study of certain glands and the hormones they regulate. He believed the effects of aging and decreased hormones contributed to criminality, weak morality, and poor physical attributes. Transplanting the testicles of younger men into those who were older would restore masculinity, he thought.

Stanley began by using the testicles of executed prisoners — but he ran into a supply shortage. He solved this by using the testicles of animals, including goats and deer. At first, he physically implanted the testicles directly into the inmates. But that had complications, so he switched to a new plan: He ground up the animal testicles into a paste, which he injected into prisoners’ abdomens. By the end of his time at San Quentin, Stanley did an estimated 10,000 testicular procedures .

The Oncologist Who Injected Cancer Cells Into Patients and Prisoners

During the 1950s and 1960s, Sloan-Kettering Institute oncologist Chester Southam conducted research to learn how people’s immune systems would react when exposed to cancer cells. In order to find out, he injected live HeLa cancer cells into patients, generally without their permission. When patient consent was given, details around the true nature of the experiment were often kept secret. Southam first experimented on terminally ill cancer patients, to whom he had easy access. The result of the injection was the growth of cancerous nodules , which led to metastasis in one person.

Next, Southam experimented on healthy subjects , which he felt would yield more accurate results. He recruited prisoners, and, perhaps not surprisingly, their healthier immune systems responded better than those of cancer patients. Eventually, Southam returned to infecting the sick and arranged to have patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, NY, injected with HeLa cells. But this time, there was resistance. Three doctors who were asked to participate in the experiment refused, resigned, and went public.

The scandalous newspaper headlines shocked the public, and legal proceedings were initiated against Southern. Some in the scientific and medical community condemned his experiments, while others supported him. Initially, Southam’s medical license was suspended for one year, but it was then reduced to a probation. His career continued to be illustrious, and he was subsequently elected president of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The Aptly Named ‘Monster Study’

Pioneering speech pathologist Wendell Johnson suffered from severe stuttering that began early in his childhood. His own experience motivated his focus on finding the cause, and hopefully a cure, for stuttering. He theorized that stuttering in children could be impacted by external factors, such as negative reinforcement. In 1939, under Johnson’s supervision, graduate student Mary Tudor conducted a stuttering experiment, using 22 children at an Iowa orphanage. Half received positive reinforcement. But the other half were ridiculed and criticized for their speech, whether or not they actually stuttered. This resulted in a worsening of speech issues for the children who were given negative feedback.

The study was never published due to the multitude of ethical violations. According to The Washington Post , Tudor was remorseful about the damage caused by the experiment and returned to the orphanage to help the children with their speech. Despite his ethical mistakes, the Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing Clinic at the University of Iowa bears Johnson's name and is a nod to his contributions to the field.

The Dermatologist Who Used Prisoners As Guinea Pigs

One of the biggest breakthroughs in dermatology was the invention of Retin-A, a cream that can treat sun damage, wrinkles, and other skin conditions. Its success led to fortune and fame for co-inventor Albert Kligman, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania . But Kligman is also known for his nefarious dermatology experiments on prisoners that began in 1951 and continued for around 20 years. He conducted his research on behalf of companies including DuPont and Johnson & Johnson.

Kligman’s work often left prisoners with pain and scars as he used them as study subjects in wound healing and exposed them to deodorants, foot powders, and more for chemical and cosmetic companies. Dow once enlisted Kligman to study the effects of dioxin, a chemical in Agent Orange, on 75 inmates at Pennsylvania's Holmesburg Prison. The prisoners were paid a small amount for their participation but were not told about the potential side effects.

In the University of Pennsylvania’s journal, Almanac , Kligman’s obituary focused on his medical advancements, awards, and philanthropy. There was no acknowledgement of his prison experiments. However, it did mention that as a “giant in the field,” he “also experienced his fair share of controversy.”

The Endocrinologist Who Irradiated Prisoners

When the Atomic Energy Commission wanted to know how radiation affected male reproductive function, they looked to endocrinologist Carl Heller . In a study involving Oregon State Penitentiary prisoners between 1963 and 1973, Heller designed a contraption that would radiate their testicles at varying amounts to see what effect it had, particularly on sperm production. The prisoners also were subjected to repeated biopsies and were required to undergo vasectomies once the experiments concluded.

Although study participants were paid, it raised ethical issues about the potential coercive nature of financial compensation to prison populations. The prisoners were informed about the risks of skin burns, but likely were not told about the possibility of significant pain, inflammation, and the small risk of testicular cancer.

- personal health

- behavior & society

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Stanford Prison Experiment

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

- Participants

- Setting and Procedure

In August of 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues created an experiment to determine the impacts of being a prisoner or prison guard. The Stanford Prison Experiment, also known as the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, went on to become one of the best-known studies in psychology's history —and one of the most controversial.

This study has long been a staple in textbooks, articles, psychology classes, and even movies. Learn what it entailed, what was learned, and the criticisms that have called the experiment's scientific merits and value into question.

Purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment

Zimbardo was a former classmate of the psychologist Stanley Milgram . Milgram is best known for his famous obedience experiment , and Zimbardo was interested in expanding upon Milgram's research. He wanted to further investigate the impact of situational variables on human behavior.

Specifically, the researchers wanted to know how participants would react when placed in a simulated prison environment. They wondered if physically and psychologically healthy people who knew they were participating in an experiment would change their behavior in a prison-like setting.

Participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment

To carry out the experiment, researchers set up a mock prison in the basement of Stanford University's psychology building. They then selected 24 undergraduate students to play the roles of both prisoners and guards.

Participants were chosen from a larger group of 70 volunteers based on having no criminal background, no psychological issues , and no significant medical conditions. Each volunteer agreed to participate in the Stanford Prison Experiment for one to two weeks in exchange for $15 a day.

Setting and Procedures

The simulated prison included three six-by-nine-foot prison cells. Each cell held three prisoners and included three cots. Other rooms across from the cells were utilized for the jail guards and warden. One tiny space was designated as the solitary confinement room, and yet another small room served as the prison yard.

The 24 volunteers were randomly assigned to either the prisoner or guard group. Prisoners were to remain in the mock prison 24 hours a day during the study. Guards were assigned to work in three-man teams for eight-hour shifts. After each shift, they were allowed to return to their homes until their next shift.

Researchers were able to observe the behavior of the prisoners and guards using hidden cameras and microphones.

Results of the Stanford Prison Experiment

So what happened in the Zimbardo experiment? While originally slated to last 14 days, it had to be stopped after just six due to what was happening to the student participants. The guards became abusive and the prisoners began to show signs of extreme stress and anxiety .

It was noted that:

- While the prisoners and guards were allowed to interact in any way they wanted, the interactions were hostile or even dehumanizing.

- The guards began to become aggressive and abusive toward the prisoners while the prisoners became passive and depressed.

- Five of the prisoners began to experience severe negative emotions , including crying and acute anxiety, and had to be released from the study early.

Even the researchers themselves began to lose sight of the reality of the situation. Zimbardo, who acted as the prison warden, overlooked the abusive behavior of the jail guards until graduate student Christina Maslach voiced objections to the conditions in the simulated prison and the morality of continuing the experiment.

One possible explanation for the results of this experiment is the idea of deindividuation , which states that being part of a large group can make us more likely to perform behaviors we would otherwise not do on our own.

Impact of the Zimbardo Prison Experiment

The experiment became famous and was widely cited in textbooks and other publications. According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, the Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated the powerful role that the situation can play in human behavior.

Because the guards were placed in a position of power, they began to behave in ways they would not usually act in their everyday lives or other situations. The prisoners, placed in a situation where they had no real control , became submissive and depressed.

In 2011, the Stanford Alumni Magazine featured a retrospective of the Stanford Prison Experiment in honor of the experiment’s 40th anniversary. The article contained interviews with several people involved, including Zimbardo and other researchers as well as some of the participants.

In the interviews, Richard Yacco, one of the prisoners in the experiment, suggested that the experiment demonstrated the power that societal roles and expectations can play in a person's behavior.

In 2015, the experiment became the topic of a feature film titled The Stanford Prison Experiment that dramatized the events of the 1971 study.

Criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment

In the years since the experiment was conducted, there have been a number of critiques of the study. Some of these include:

Ethical Issues

The Stanford Prison Experiment is frequently cited as an example of unethical research. It could not be replicated by researchers today because it fails to meet the standards established by numerous ethical codes, including the Code of Ethics of the American Psychological Association .

Why was Zimbardo's experiment unethical?

Zimbardo's experiment was unethical due to a lack of fully informed consent, abuse of participants, and lack of appropriate debriefings. More recent findings suggest there were other significant ethical issues that compromise the experiment's scientific standing, including the fact that experimenters may have encouraged abusive behaviors.

Lack of Generalizability

Other critics suggest that the study lacks generalizability due to a variety of factors. The unrepresentative sample of participants (mostly white and middle-class males) makes it difficult to apply the results to a wider population.

Lack of Realism

The Zimbardo Prison Experiment is also criticized for its lack of ecological validity. Ecological validity refers to the degree of realism with which a simulated experimental setup matches the real-world situation it seeks to emulate.

While the researchers did their best to recreate a prison setting, it is simply not possible to perfectly mimic all the environmental and situational variables of prison life. Because there may have been factors related to the setting and situation that influenced how the participants behaved, it may not truly represent what might happen outside of the lab.

Recent Criticisms

More recent examination of the experiment's archives and interviews with participants have revealed major issues with the research method , design, and procedures used. Together, these call the study's validity, value, and even authenticity into question.

These reports, including examinations of the study's records and new interviews with participants, have also cast doubt on some of its key findings and assumptions.

Among the issues described:

- One participant suggested that he faked a breakdown so he could leave the experiment because he was worried about failing his classes.

- Other participants also reported altering their behavior in a way designed to "help" the experiment .

- Evidence suggests that the experimenters encouraged the guards' behavior and played a role in fostering the abusive actions of the guards.

In 2019, the journal American Psychologist published an article debunking the famed experiment. It detailed the study's lack of scientific merit and concluded that the Stanford Prison Experiment was "an incredibly flawed study that should have died an early death."

In a statement posted on the experiment's official website, Zimbardo maintains that these criticisms do not undermine the main conclusion of the study—that situational forces can alter individual actions both in positive and negative ways.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is well known both inside and outside the field of psychology . While the study has long been criticized for many reasons, more recent criticisms of the study's procedures shine a brighter light on the experiment's scientific shortcomings.

Stanford University. About the Stanford Prison Experiment .

Stanford Prison Experiment. 2. Setting up .

Sommers T. An interview with Philip Zimbardo . The Believer.

Ratnesar R. The menace within . Stanford Magazine.

Jabbar A, Muazzam A, Sadaqat S. An unveiling the ethical quandaries: A critical analysis of the Stanford Prison Experiment as a mirror of Pakistani society . J Bus Manage Res . 2024;3(1):629-638.

Horn S. Landmark Stanford Prison Experiment criticized as a sham . Prison Legal News .

Bartels JM. The Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory psychology textbooks: A content analysis . Psychol Learn Teach . 2015;14(1):36-50. doi:10.1177/1475725714568007

American Psychological Association. Ecological validity .

Blum B. The lifespan of a lie . Medium .

Le Texier T. Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment . Am Psychol . 2019;74(7):823-839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401

Stanford Prison Experiment. Philip Zimbardo's response to recent criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Unethical Research Practices to Avoid: Examples & Detection

Almost every aspect of human life is guided by guidelines, rules, and regulations. That is why, from time immemorial, there have been set ethics and rules that serve as a guide and moderator in human activities.

Without these recognized ethics, everyone will approach issues in ways they deem appropriate. This applies to the research and research community.

Research guidelines provide information about accepted research ethics to the research community and the researchers. These guidelines provide ethics, advice, and guidance. They help researchers develop ethical discretion and also to prevent the researchers from committing scientific misconduct, and promote good scientific practice.

We are going to discuss research ethics, what they mean, how they are adopted, how important they are, and how they affect research and research institutions.

What are Research Ethics?

Ethics are a set of rules, which can be broadly written and unwritten. They govern a human’s behavioral expectations and that of others.

While society broadly agrees on some ethical values such as murder is terrible and disallowed, a wide variation also exists on how we can interpret these set values in practice.

Now research ethics refers to the values and the norms an institution has put in place to help regulate scientific activities. It is a collection of scientific morals in the line of duty. This guideline specifies the traits or behaviors that are recognized by the research community based on the general ethics of science and society at large.

Research guidelines are binding on both the researcher and the institution. This is because there are responsibilities to be carried out by both the researcher and the institution to ensure that their research is reliable. However, it is important that the institutions are clear on the research ethics roles and responsibilities at every point. Part of the duties of the institution is to have good administrational management and funding that would allow researchers to comply with designed ethical guidelines and norms.

Read: Research Bias: Definition, Types + Examples

The guidelines primarily cover research and other research-related activities, which include teaching, dissemination of research information, and also the management of institutions. Research ethical guidelines are also used as tools in the assessment of an individual case in the planning of research and even when reporting or publishing the outcomes and findings of that study.

The research ethics guideline covers the projects of students at all levels, and that of the doctoral research fellows. It is also the responsibility of the institution to provide relevant training regarding research ethics to the students and doctoral research Fellows. This is because the research norms and guidelines apply to all researches regardless of whether they are commissioned research, applied research, or basic research.

Research conducted by the public, or private institutions is also subjected to these guidelines and ethics. Consulting firms that perform research-related tasks, such as systematic acquisition and information processing about individuals, groups, and organizations, are also not excluded.

Read: Consent Letter: Writing Guide, Types, [+12 Consent Samples]

There are guidelines regulating research at different levels based on recognized norms for research ethics. We are going to look at these research norms below.

- There are norms for good scientific practice. They relate to finding accuracy and relevant knowledge in research. These norms are Originality, trustworthiness, academic freedom, and openness.

- There are norms for the research communities. They guide the relationship between the people that partake together in research. These norms are respect, accountability, confidentiality, integrity, impartiality, constructive criticism, informed and free consent, and human dignity.

- There are norms that guide the researchers’ relationship with the rest of society. These norms are social responsibility, dissemination of research, and independence.

The first two groups listed above are internal ethical norms. They relate to regulating the research communities, while the other relates to the relationship that exists between the research and the outside world or the society. Many times, the lines between these norms get blurred.

Research ethics are the standard ethics set by the supervising institution or bodies to govern how scientific research and other types of research are conducted in various research institutions such as the universities, and also moderate how they are interpreted.

Read: Sampling Bias: Definition, Types + [Examples]

Why is Research Ethics Important?

The aim of research ethics is to guide researchers to conduct their studies and report their findings without deception or intent to directly or indirectly cause harm to their subjects or any member of society, as the case may be.

Also, research ethics establish the validity of a researcher’s study or research. It establishes that the research is authentic and error/bias-free. This will give the researcher credibility within the institution and in the public.

Research ethics also ensure the safety of research or study subjects and the researcher. This is because it is a must that all researchers follow these guidelines.

Another importance of research ethics is that it shows that your research publications are not plagiarized, and your readers are not reading unverified data. This is achieved through the research manuscript. Your research findings must adhere to the set guidelines.

The last point to consider is that research ethics provide the researcher with a sense of responsibility. This makes it easy to find appropriate solutions in the case of any misconduct.

Read: Systematic Errors in Research: Definition, Examples

Examples of Unethical Research Practices

Here’s a list of unethical practices every researcher must avoid

1. Duplicate publication

It is unethical for a researcher to submit a research paper or publication that has two or more seminal journals which could be with or without acknowledgment of these other journals. This practice is known as duplicate submission or duplicate publication.

Some authors practice duplication of publication so as to increase their numbers of submissions; however, it is unethical and it also amounts to the wasting of time of the publication resources and the journal reviewers why it also serves no benefits today to the scientific community and humanity at large.

You can only submit your research paper to just one journal.

2. Research data falsification

the falsification or fabrication of research data occurs when a researcher tries to manipulate the procedures used in conducting research or the important findings just to have the researcher’s desired result.

Recording non-existent data or falsifying a data recording is known as research fabrication.

Research data fabrication is common in the pharmaceutical industry. They do this fabrication 2 market a specific drug today to the general public without considering the drug’s side effects. This act is unethical and it is also a wastage of the limited resources available for research.

This can result in revoking the physician’s clinical license, the prosecution of the physician, and also create huge mistrust in the mind of the public.

3. Plagiarism

Plagiarism is a huge offense in the research community. It is the practice of taking another person’s research or work or even idea and inculcating it in your own writing without giving them the dual credit. In some cases, just for recognition, the researcher can even use another person’s research as their own publication journal.

In other cases, the researcher may change the letters of someone else’s publication to their own words without referencing the original author. This is known as self-plagiarism.

With technology, there are more tools to detect plagiarism. This means it is now very easy for journal editors to detect plagiarism. Plagiarism may not be intentional sometimes, it may just happen accidentally. However, you can avoid it by referencing all the sources you used in writing your own scientific journal.

Ensure that all the authors whose work you have used are properly cited in your paper, regardless of if they’re from previous publications.

4. Authorship Conflict

ICMJE (The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors) guidelines provided that anyone who has contributed to the conception, the designing of research data, contributed to the data analysis, helped to draft or revise the journal and seek approval before the journal is published has an authorship claim to the journal.

Now an authorship conflict can arise if the name of a person who has contributed to the journal in any form is not included in the publication.

If one of the persons whose name was cited in the journal does not give consent or agree to its publication. That is an authorship conflict and it is unethical.

If the name of one additional author is cited while the name of an already cited author is removed, whether before publication or after publication, it is an authorship conflict.

Another cause of authorship conflict is citing a person’s name based on “senior in practice” or family affiliation when the said person has contributed nothing to the research and the documentation of the research findings.

Authorship conflict can be avoided before conducting the research by selecting the authors in the beginning and also by the journals asking the authors to submit a checklist that contains the criteria for authorship.

5. Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest arises in research when the author or the researcher gets influenced by financial reasons or personal issues that ultimately affect the quality of the outcome of the study.

When these conflicts of interest arise, which could be personal conditions and financial consideration or other types of conflicts, the researcher should truthfully disclose the current situation to the editorial team, and do so completely without leaving out a detail.

Read: Undercoverage Bias: Definition, Examples in Survey Research

Research ethical guidelines are designed to guide researchers in research conduct and publications.

This is why all researchers should develop habits of self-consciousness, self-restraint, and self of responsibility. This will enable them to take importance to the welfare of the members of the research community, the public, and their own reputation. Bearing all this in mind what wood prevents them from partaking in any misconduct in their research and publication.

Implications and Consequences of Unethical Research Practices

A researcher’s ethical obligations are to be taken seriously because they are truly no laughing matter. Here are the things at stake if violated.

- A researcher risks an unapproved study or publication if the research proposal submitted to the supervising institution does not meet the research ethical requirements. This implies that the researcher will not be allowed to proceed with the research until the ethical conditions have been met according to the standard by the supervising institution.

- If you have gotten a go-ahead for your study or research, failure to comply with the guidelines can result in your research being declared void and retracted. This means that you have to follow every step throughout the research else you can face disciplinary actions.

- If your research publication is connected to your doctorate degree, your doctorate title might be revoked. If the nature of your ethics breach is criminal, then the supervising institution can take legal action against the researcher. This may lead to prison sentences for the researcher.

- Also, an unethical omission can cause the characteristics of the researcher to be questioned in terms of reliability, and also, the validity of the test will be questioned.

- Unethical conduct in research can put in bad media coverage and damage the reputation of you and your research institution.

Researchers should remember the consequence of unethical conduct is humiliation. Aside from the loss of reputation, there could be legal consequences. That is why researchers should not take shortcuts when conducting their research.

Retraction watch is a website where retracted researchers are publicized and no researcher would want to be featured on this website for unethical conduct.

Read: Type I vs Type II Errors: Causes, Examples & Prevention

How to Detect Unethical Research Practices

Here are some tools and mechanisms you can use to prevent and detect unethical practices.

1. Management responsibility

In its day-to-day dealings, the management must maintain the highest standards of integrity. This is because if senior management is dishonest and corrupt, they will spread dishonest and fraudulent acts to all levels. It is their responsibility to be the highest standards when it comes to integrity.

The management is to serve as an example for all in the research organization to follow by pointing out correct and acceptable behavior to the staff. To ensure maximum security, they must make sure that the organization has all the procedures and control measures in place to ensure maximum security.

2. Code of ethics

There must be a setup code of ethics for all employees to follow in every establishment. This should be a formal statement containing ethical codes of conduct for the organization’s employees to follow. The Code of Ethics should unambiguously state the type of behavior expected from the employees, and what is unacceptable.

3. Personnel policies and procedures

If policies and procedures are open and fair, and also efficient personnel is in an organization, the organization’s exposure to fraud will be minimal. Organizations should consider putting effective policies in place.

Ethical Principles in Research

Respect for individuals.

- Researchers must base their study on the fundamental respect for human dignity.

- The research must respect their privacy. The autonomy and integrity of the individual must be protected.

- It must perform its duty to inform participants of what they’re being given. They must be provided with adequate information about the research and the purpose of the research.

- It must derive consent to notify. The participants must willingly grant consent before the research can proceed.

- It must also practice confidentiality. All personal data must be handled with utmost care and confidentiality.

- There must also be a responsibility to protect children and not cause others harm.

Respect for Institutions

- The research must be in accordance with the rules of the public administration.

- There must be adequate respect given to private establishments that do not want to give out their data or information.

- The interest of the vulnerable groups must be protected at all times.

- Research should be carried out on other cultures appropriately. And these cultures must be respected.

- Cultural monuments such as archives, artifacts, and texts must be treated with maximum care and preserved.

Explore: 21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2021

Formplus Features for Ethical Research

If you want to conduct a survey or make use of questionnaires in your research, the best website to use is Formplus.

Formplus has all you need to develop your form, administer your form, gather the data from your survey or questionnaire, and interpret it.

Formplus also has in place all the requirements a researcher needs to follow ethical guidelines. Your forms are secured, private, and protected.

- GDPR-Compliant

The GDPR-compliant consent form helps you to maintain the European Union’s data privacy laws. You can collect personal information such as names, emails, phone numbers, and addresses using the GDPR compliant form builder on Formplus.

- Privacy Policy and Security

The privacy protection policy of Formplus is so transparent that it will tell you what the data collected from you will be used for, and who it is shared with. Also, your data is so secure that not even Formplus can access it without your permission.

Security is also 100% guaranteed. Formplus takes extra steps to ensure the privacy of its users is protected. Formplus website complies with all international laws and requirements you can think of. All your sensitive information is protected online and offline.

Rules and guidelines are important. Not only because they give you instructions on how to carry out a procedure in research, but also because they make you responsible and respectable humans in society.

There are set ethical guidelines that protect the researcher, the research community, and the general public. It is in a researcher’s best interest to follow these laid down rules because the consequences are a long-lasting dent to whoever is involved and that might even be the end of their career.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- code of ethics

- data falsification

- duplicate publication

- principles of research

- research ethics

- unethical research

- unethical research practices

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Exploratory Research: What are its Method & Examples?

Overview on exploratory research, examples and methodology. Shows guides on how to conduct exploratory research with online surveys

Recall Bias: Definition, Types, Examples & Mitigation

This article will discuss the impact of recall bias in studies and the best ways to avoid them during research.

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Market Research: Types, Methods & Survey Examples

A complete guide on market research; definitions, survey examples, templates, importance and tips.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Common Ethical Issues In Research And Publication

Ng chirk jenn.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Dr Ng Chirk Jenn, Senior lecturer, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Tel: 03-79492306, Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Collection date 2006.

INTRODUCTION

Research is the pillar of knowledge, and it constitutes an integral part of progress. In the fast-expanding field of biomedical research, this has improved the quality and quantity of life. Historically, medical doctors have been in the privileged position to carry out research, especially in clinical research which involves people. They are able to control “life and death” of patients and have free access to their confidential information. Moreover, medical researchers have also enjoyed immunity from accountability due to high public regard for science and medicine. This has resulted in some researchers conducting unethical researches. For instance, in World War II, medical doctors had conducted unethical experiments on human in the name of science, resulting in harm and even death in some cases. 1 More recently, the involvement of pharmaceutical industry in clinical trials have raised issues about how to safeguard patient’s care and to ensure the published research findings are objective. 2

In the light of these ethical controversies, the Declaration of Helsinki was established to inform biomedical researchers the principles of clinical research. 3 This declaration highlighted a tripartite guidelines for good clinical practice which include respect for the dignity of the person; research should not override the health, well-being and care of subjects; principles of justice. Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) was also founded in 1997 to address the breaches of research and publication ethics. 4

How do we apply all these principles in our daily conduct of research? This paper will discuss different ethical issues in research, including study design and ethical approval, data analysis, authorship, conflict of interest and redundant publication and plagiarism. I have also included two case scenarios in this paper to illustrate common ethical issues in research and publication.

ETHICAL ISSUES IN RESEARCH

1. study design and ethics approval.

According to COPE, “good research should be well adjusted, well-planned, appropriately designed, and ethically approved. To conduct research to a lower standard may constitute misconduct.” 3 This may appear to be a stringent criterion, but it highlights the basic requirement of a researcher is to conduct a research responsibly. To achieve this, a research protocol should be developed and adhered to. It must be carefully agreed to by all contributors and collaborators, and the precise roles of each team member should be spelled out early, including matters of authorship and publications. Research should seek to answer specific questions, rather than just collect data.

It is essential to obtain approval from the Institutional Review Board, or Ethics Committee, of the respective organisations for studies involving people, medical records, and anonymised human tissues. The research proposal should discuss potential ethical issues pertaining to the research. The researchers should pay special attention to vulnerable subjects to avoid breech of ethical codes (e.g. children, prisoners, pregnant women, mentally challenged, educationally and economically disadvantaged). Patient information sheet should be given to the subjects during recruitment, detailing the objectives, procedures, potential benefits and harms, as well as rights to refuse participation in the research. Consent should be explained and obtained from the subjects or guardians, and steps should be taken to ensure confidentiality of information provided by the subjects.

2. Data analysis

It is the responsibility of the researcher to analyse the data appropriately. Although inappropriate analysis does not necessarily amount to misconduct, intentional omission of result may cause misinterpretation and mislead the readers. Fabrication and falsification of data do constitute misconduct. For example, in a clinical trial, if a drug is found to be ineffective, this study should be reported. There is a tendency for the researchers to under-report negative research findings, 5 and this is partly contributed by pressure from the pharmaceutical industry which funds the clinical trial.

To ensure appropriate data analysis, all sources and methods used to obtain and analyse data should be fully disclosed. Failure to do so may lead the readers to misinterpret the results without considering possibility of the study being underpowered. The discussion section of a paper should mention any issues of bias, and explain how they have been dealt with in the design and interpretation of the study.

3. Authorship

There is no universally agreed definition of authorship. 6 It is generally agreed that an author should have made substantial contribution to the intellectual content, including conceptualising and designing the study; acquiring, analysing and interpreting the data. The author should also take responsibility to certify that the manuscript represents valid work and take public responsibility for the work. Finally, an author is usually involved in drafting or revising the manuscript, as well as approving the submitted manuscript. Data collection, editing of grammar and language, and other routine works by itself, do not deserve an authorship.

It is crucial to decide early on in the planning of a research who will be credited as authors, as contributors, and who will be acknowledged. It is also advisable to read carefully the “Advice to Authors” of the target journal which may serve as a guide to the issue of authorship.

4. Conflicts of interest

This happens when researchers have interests that are not fully apparent and that may influence their judgments on what is published. These conflicts include personal, commercial, political, academic or financial interest. Financial interests may include employment, research funding, stock or share ownership, payment for lecture or travel, consultancies and company support for staff. This issue is especially pertinent in biomedical research where a substantial number of clinical trials are funded by pharmaceutical company.

Such interests, where relevant, should be discussed in the early stage of research. The researchers need to take extra effort to ensure that their conflicts of interest do not influence the methodology and outcome of the research. It would be useful to consult an independent researcher, or Ethics Committee, on this issue if in doubt. When publishing, these conflicts of interest should be declared to editors, and readers will judge for themselves whether the research findings are trustworthy.

5. Redundant publication and plagiarism

Redundant publication occurs when two or more papers, without full cross reference, share the same hypothesis, data, discussion points, or conclusions. However, previous publication of an abstract during the proceedings of meetings does not preclude subsequent submission for publication, but full disclosure should be made at the time of submission. This is also known as self-plagiarism. In the increasing competitive environment where appointments, promotions and grant applications are strongly influenced by publication record, researchers are under intense pressure to publish, and a growing minority is seeking to bump up their CV through dishonest means. 7

On the other hand, plagiarism ranges from unreferenced use of others’ published and unpublished ideas, including research grant applications to submission under “new” authorship of a complete paper, sometimes in different language.

Therefore, it is important to disclose all sources of information, and if large amount of other people’s written or illustrative materials is to be used, permission must be sought.

It is the duty of the researcher to ensure that research is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner from planning to publication. Researchers and authors should familiarise themselves with these principles and follows them strictly. Any potential ethical issues in research and publication should be discussed openly within the research team. If in doubt, it is advisable to consult the respective institutional review board (IRB) for their expert opinions.

Case Scenario 1:

“A community survey on prevalence of domestic violence among secondary school students.”

Who should we obtain the consent? Students, parents, teachers or Ministry of Education?

To conduct this study, we need to seek approval from the Ministry of Education and permission from the school principal. However, consent should be taken from parents, who are the legal guardians of the students.

If the results show that 50% of the students have ever been abused, should I report them to the police?

These ethical issues should be discussed at the proposal stage, and the participants/guardians should be informed about the decision to report to the police while taking the consent. This will potentially affect the response rate; but this is also the responsibility of the researcher to protect the participants and their families.

I have decided to publish it. Can I send an abstract for presentation as part of the conference proceedings, and later submit similar abstract with the full text for publication. Is that redundant publication?

Yes, you can. However, you need to declare to the publisher that you have presented the paper in the conference. Redundant publication happens when an author has submitted two papers with similar objective, methodology and results, without cross referencing.

Can I submit the same paper in a different language?

Yes, you can. However, you have to declare to the publisher that you have published an identical paper in a different language.

Case Scenario 2:

“Does HRT improve vasomotor symptoms among menopausal women in a Malaysian primary care clinic?”

Some people say it is “unethical” to do this study because it has been proven in many studies. But no such research has ever been done locally!

HRT has been proven to be effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms in many well-designed studies. It is inappropriate for the researcher to repeat an established therapy which may potentially cause harm to them (e.g. deep vein thrombosis and breast cancer). However, it is appropriate to repeat research if the researchers feel that it may yield a different outcome in the local setting based on a firm theoretical basis.

Do we still need to obtain ethics approval if it is part of daily clinical practice?

Yes, even though it is part of our normal practice, all research involving human subjects, especially when it involves drugs, should be subjected to ethics approval. (E.g. “How did the researchers ensure that they explain to the patients fully about the potential harm of HRT?”)

I’m worried that if I start explaining to the participants about the possibility of Ca breast, they won’t want to participate. How can I “play down” this possible side effect?

As mentioned earlier, it is the duty of the researcher to ensure that the participant understands the benefits and risks of the treatment. The information should be conveyed in an objectively manner in the patient information sheet. Any queries from the patient should be answered truthfully, and it is the patient’s rights to refuse to participate in the research.

While writing the introduction and discussion of my paper/thesis, I copied sentences from some papers. But I referred to them in my reference. Is that acceptable?

It is acceptable to quote sentences from a paper as long as they are duly referenced.

- 1. Human D, Fluss SS. World Medical Association; 2001. The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: historical and contemporary perspectives. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality. BMJ. 2003;326:1167–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. World Medical association. 2004. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) 2005. Guidelines on good publication and the Code of Conduct. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Smith R. Medical journals are an extension of the marketing arm of pharmaceutical companies. PLoS Med. 2005;2:100–2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020138. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Medical Research Council. London: MRC; 1998. MRC Guidelines for good clinical practice in clinical trials. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Giles J. Taking on the cheats. Nature. 2005;435:258–9. doi: 10.1038/435258a. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (104.6 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Research Misconduct: Reasons and Types of Research Misconduct

Science and is built on the foundation of integrity and trust, and questionable research practices or research misconduct is counter-productive to the production and use of scientific knowledge. Not only does it dilute the research findings and lead to misinterpretations, it also leads to an overall loss of trust in the work done by the scientific community. Hence any kind of research misconduct or malpractice is considered a grave issue that needs to be strictly avoided. This makes it critical for scientists and researchers to gain an understanding of the best practices and ethical research to avoid unknowingly venturing into such grey areas. This article delves into what is scientific misconduct, different types of research misconduct, and 5 reasons for committing research misconduct.

Table of Contents

What is research misconduct?

Research misconduct or scientific misconduct refers to actions and behaviors by researchers that fail to honor the integrity of research. The Office of Research Integrity defines research misconduct as the falsification, fabrication or plagiarism in conducting, planning, reporting or reviewing research [1] . Simply put, research misconduct is any intentional deviation from ethical research practices. A scientific misconduct example is deliberately creating names and details of survey participants for the purpose of generating data, which is an unethical research practice. Other common scientific misconduct examples include modifying or omitting data to influence study findings or withholding critical information from human participants in clinical trials or experiments.

Types of research misconduct

There are different types of research misconduct or scientific misconduct and unethical practices in research. The most serious ethical infractions are fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism in research. Some of the most common types of research misconduct have been detailed below.

- Fabrication: This refers to the practice of making up data without having done the required research. Research misconduct covers not only the act of fabrication, but also the sharing, discussing, or publishing of this fabricated data or results.

- Falsification: This type of scientific misconduct involves the wilful manipulation of data, materials, processes, or equipment to arrive at a predefined conclusion. One such example would be selectively omitting or changing data, which results in the erroneous representation of research results.

- Plagiarism: This is one of the most common types of scientific misconduct, and involves using another person’s ideas, content, writing, processes, or results without giving due credit. This also includes self-plagiarism , which occurs when you replicate your own writings or ideas from previously published research without providing proper credit.

- Authorship: This type of scientific misconduct in research includes attempts to assign false authorships without adequate contribution to research, mentioning authors without their consent, or failing to include authors who are original contributors. Naming authors in the wrong order or incorrectly is also considered unethical.

- Conflicts of interest: This can be classified under general scientific misconduct and involves lapses by researchers in declaring any conflict of interests in their research work. These conflicts of interest may be financial, personal, and professional and need to be reported appropriately to avoid any ethical issues.

- Approvals: One of the most important aspect of research that involves human or animal subjects is adhering to all the ethical approvals and legal guidelines. Non-compliance with this ethical mandate is considered a serious type of research misconduct.

5 Reasons for committing research misconduct

Over time there have been varied reasons for researchers to succumb to scientific misconduct. Let us look at 5 reasons for committing research misconduct.

- Career pressures : An important factor often associated with research misconduct is the undue pressure researchers face. They need to conduct original research in a fast-paced environment, publish frequently in peer reviewed journals, and procure funding for research projects to advance their research career. This along with the need to juggle multiple responsibilities against tight deadlines create undue stress to succeed at any cost, leading to a lack of care or even deliberate research misconduct.

- Researcher’s personal psychology: Some researchers may be overly driven by a desire to quickly attain a strong professional reputation or even financial gains, which could push them to research misconduct.

- Lack of appropriate training and skills: The lack of training on the best practices and ethical guidelines to be followed as researchers is another reason for research misconduct. Poor awareness and understanding on these issues often lead to unethical conduct in research.

- Insufficient supervision or mentoring: Related to the point above, this relates to situations where researchers, especially early career researchers, fail to receive sufficient and appropriate support from immediate supervisors or from their affiliated institution. A lack of oversight and guidance may knowingly or unknowingly lead to research misconduct.

- Inadequate knowledge: Scientific misconduct can occur if the researcher does not have sufficient knowledge of the topic/subject or on research best practices. Carelessness when conducting research and reporting it are also considered research misconduct.

Researchers and institutions should adopt various measures to prevent the occurrence of scientific misconduct. The most significant aspect is the provision of adequate training that builds researcher knowledge as to what constitutes research misconduct and how best to avoid this. It is vital for institutions to have guidelines and procedures related to good research practices and ethical conduct and ensure it is disseminated effectively among their research community.

It is also important for supervisors to mentor budding researchers on the correct procedures and practices, including what constitutes ethical misconduct in research. Without sufficient awareness, it will be difficult to effectively address this important issue. Finally, researchers must take it upon themselves to check the global standards and guidelines for ethical research to ensure they are not engaging in any scientific misconduct.

Q: What are the consequences of research misconduct?

Research misconduct, which includes fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, can lead to severe repercussions. These may involve damage to a researcher’s reputation, loss of funding, retraction of published papers, and academic sanctions. Additionally, it undermines scientific integrity, erodes public trust, and hampers the advancement of knowledge. Institutions may conduct investigations, resulting in job loss and legal actions. Overall, research misconduct has far-reaching negative impacts on individuals, institutions, and the scientific community as a whole.

Q: What are the major causes of research misconduct?

Research misconduct arises from various factors such as pressure to publish, competition for grants, and career advancement. Lack of supervision, inadequate training in ethical research practices, and poor research culture can contribute. High publication demands may drive researchers to cut corners, leading to fabrication of data, falsification of results, and even plagiarism. Ethical lapses might also stem from personal ambition, greed, or the desire to bolster one’s professional standing, ultimately undermining the credibility of scientific work.

Q: What is meant by falsification in research?

Falsification refers to the deliberate manipulation or alteration of research data, methods, or results to present inaccurate or misleading information. This unethical practice involves misrepresenting findings by selectively omitting data, changing results, or altering graphs and images. Falsification distorts the truth, compromises research integrity, and can have profound implications for scientific progress and public trust in research outcomes.

Q: What are some examples of scientific misconduct?

Scientific misconduct encompasses various behaviors such as plagiarism, where one presents others’ work as their own. Fabrication involves inventing data or results that do not exist. Falsification includes altering or manipulating data to fit a desired outcome. Misleading authorship and inadequate citation of sources are also forms of misconduct. Additionally, improper handling of human or animal subjects, failure to disclose conflicts of interest, and misrepresentation of credentials can occur. These actions breach ethical standards, erode scientific credibility, and can lead to severe consequences for individuals and the research community.

- Definition of Research Misconduct. The Office of Research Integrity. Available online at https://ori.hhs.gov/definition-research-misconduct