An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Oral Health in America Report

Oral Health in America - July 2022 Bulletin

Section 4 summary, oral health workforce, education, practice, and integration.

The oral health care system, including its workforce, education, practice, and financing, have transformed over the past 20 years to improve access to care for people who are underserved, enhance patient safety, and better integrate oral and general health care delivery. However, opportunities for further improvement remain. The oral health needs of the public, patients’ oral health literacy and behaviors, and policies shape the composition of the workforce, where new positions in dental practices and advanced training for clinicians are being developed. Practitioners can advance the accessibility and quality of the nation’s oral health by working with their colleagues in medical and behavioral systems of care, academia, insurance companies, and government agencies.

Status of Knowledge, Practice, and Perspectives

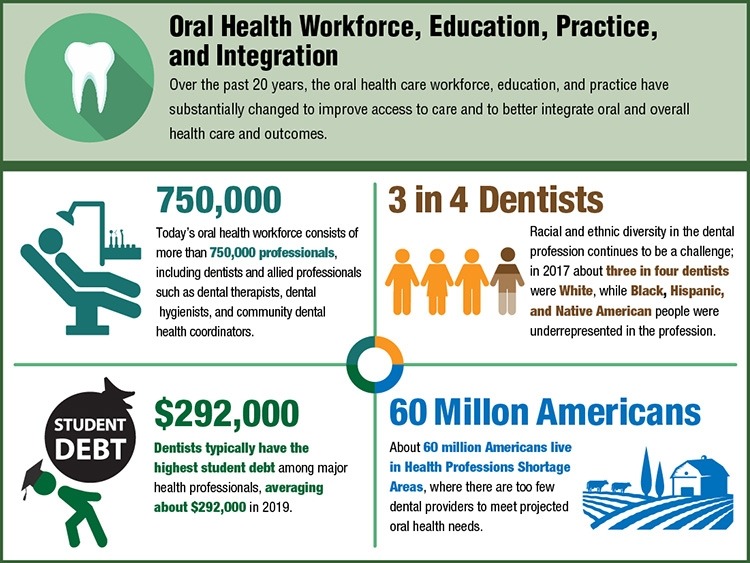

In 2020, the US oral health workforce consisted of more than 750,000 practitioners, including dentists, allied professionals such as dental hygienists, dental assistants, and dental laboratory technicians, as well as newer types of providers including dental therapists and community dental health coordinators. Private practices deliver most of the nation’s oral health care. With federal support for oral health infrastructure and service expansion of Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC), a growing number of people—nearly 5.2 million in 2020, up from about 1.4 million in 2001—have accessed oral health care services.

Advances and Challenges

Accessing oral health care can be difficult for people who are homebound due to age or disabilities and for those without access to transportation or with inflexible work hours. About 60 million Americans live in areas with too few providers to meet projected oral health needs. Some communities address these barriers by expanding dental hygienists’ roles and introducing dental therapists, who can provide preventative care and basic restorative procedures that have been traditionally carried out by dentists.

Racial and ethnic diversity in the dental profession remains a challenge. In 2017, nearly three out of four dentists were white, with disproportionate representation of Black, Hispanic, and Native American dentists. Dental education loan repayment and scholarship programs are essential tools for enhancing workforce diversity. With the high cost of dental education, dentists typically have the highest debt among health professionals; on average, dentists who graduated in 2019 had about $292,000 in student debt. High levels of debt may drive dentists to practice in affluent areas.

Promising New Directions

Co-location of dental and medical professionals, use of telehealth services, and provision of head and neck cancer or blood pressure screening by dental personnel can enhance access to and quality of oral health care. In addition, the scope of dental practice could potentially expand to include the monitoring of other chronic illnesses and vaccine delivery. Developing electronic dental records and integrating them with medical records can enable health professionals to provide coordinated services, measure oral health outcomes, and evaluate effectiveness of care. Community dental health coordinators can provide culturally sensitive health information, help people navigate health care services, and connect them with dental service providers.

Additional Takeaways

Changes are happening in dental education to address dental workforce diversity, including efforts to recruit a student population that reflects the diversity of the nation. Modifications in curriculum have also resulted in better integration of behavioral, clinical, and basic sciences, while students are being trained to provide comprehensive care and treat underserved patients in community-based settings.

Today, more people have dental insurance than 20 years ago, yet accessibility and the cost of dental care is out of reach for many. People with insurance are more likely to access dental services within a given year than those without. However, more than half of dentists do not accept public insurance, posing a challenge for Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program recipients. Improving Americans’ access to oral health care requires coordinated efforts among policymakers, insurers, and dental professionals.

Q&A with Section Editor

Q&A with Kathryn Atchison, DDS, MPH, senior editor, Section 4: Oral Health Workforce, Education, Practice, and Integration.

What are some important takeaways about this section? Dental therapists and community dental health coordinators are newer types of dental professionals who work in rural and urban areas to connect people who are underserved, including Native Americans, with dental care providers. A growing business model called Dental Service Organizations provides administrative support to dentists, enabling them to focus on providing dental care. Despite the large increase in the number of Americans with dental insurance since 2000, the current oral health care system does not meet the needs of all Americans.

What was a surprising finding? I was surprised by the variety of population groups who report being unable to fully access the US oral health care system. Money is a necessity to obtain care, and having insurance seems like an excellent remedy, but many dentists do not accept public insurance. People in the LGBTQ+ community reported difficulties in getting appointments despite anti-discrimination laws. Adults with special health care needs find few dentists who can accommodate them. Many practices are usually open only on weekdays during business hours, which challenges people whose work does not offer flexible hours or medical release time.

What should the American people know about this section of the report? Not all people can access private or public dental care, such as those who are homebound, institutionalized, have set work hours, or lack transportation to the dental office. We need to expand our offerings of non-traditional dental locations, including settings where children learn, where people live, and even where individuals shop or work so that everyone has access to dental care. These locations include day care centers, schools, assisted living centers, group homes for persons with disabilities, nursing homes, and rural community centers. Integrated managed-care organizations have also explored the value that interprofessional practice can add to patients’ overall health. Moreover, pediatricians have embraced providing oral health examinations, fluoride varnish, and oral health education to young children without dental coverage.

What is the main call to action? The main call to action is to recognize that oral health care is an essential health care need of all Americans. Therefore, policymakers and oral health system stakeholders must work together to support an oral health care workforce and delivery system that provides oral health services as part of an integrated approach that will facilitate better oral and general health.

Kathryn Atchison, DDS, MPH, is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. She received a DDS from Marquette University and a Master of Public Health from Boston University. She is a dental educator with 20 years of experience in public health as well as clinical and health services research.

Did You Know?

Text Alternative

Learn more about Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges

Subscribe to receive monthly emails that highlight information in the NIH report Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges .

Subscribe Here

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 27 October 2021

Research round-up: oral health

- Benjamin Plackett 0

Benjamin Plackett is a science journalist in Dubbo, Australia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A molar tooth with decay (red and black), which is caused by the build up of plaque. Credit: Volker Steger/SPL

Quality over quantity in old age

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02927-3

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Oral health , an editorially independent supplement produced with the financial support of third parties. About this content .

Related Articles

Sponsor feature: Improving oral health: How industry can help

- Health care

- Medical research

- Public health

Microbubble ultrasound maps hidden signs of heart disease

News & Views 06 MAY 24

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

We need more-nuanced approaches to exploring sex and gender in research

Comment 01 MAY 24

‘Orangutan, heal thyself’: First wild animal seen using medicinal plant

News 02 MAY 24

Genomics reveal unknown mutation-promoting agents at global sites

News & Views 01 MAY 24

Mechanics of human embryo compaction

Article 01 MAY 24

Male–female comparisons are powerful in biomedical research — don’t abandon them

Cells destroy donated mitochondria to build blood vessels

Multimodal decoding of human liver regeneration

Young talents in the fields of natural science and engineering technology

Apply for the 2024 Science Fund Program for Distinguished Young Scholars of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Overseas).

Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Northeastern University, China

Calling for Application! Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School Global Recruitment

To reshape graduate education as well as research and development to better serve local, national, regional, and global sustainable development.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School

Chief Editor, Physical Review X

The Chief Editor of PRX, you will build on this reputation and shape the journal’s scope and direction for the future.

United States (US) - Remote

American Physical Society

Assistant/Associate Professor, New York University Grossman School of Medicine

The Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at the NYUGSoM in Manhattan invite applications for tenure-track positions.

New York (US)

NYU Langone Health

Deputy Director. OSP

The NIH Office of Science Policy (OSP) is seeking an expert candidate to be its next Deputy Director. OSP is the agency’s central policy office an...

Bethesda, Maryland (US)

National Institutes of Health/Office of Science Policy (OSP)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- A new approach to oral...

A new approach to oral health can lead to healthier societies

- Related content

- Peer review

- Julian Fisher , director of oral and planetary health policies 1 ,

- Cleopatra Matanhire-Zihanzu , lecturer 2 ,

- Kent Buse , director 3

- 1 Center for Integrative Global Oral Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

- 2 Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Oral Health, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

- 3 Global Healthier Societies Program, George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, London, UK

- jmfisher{at}upenn.edu

New definitions of oral health provide an opportunity to change mindsets and promote innovation to tackle high levels of unmet needs, but this will only be realised with a radical change in practice, argue Julian Fisher and colleagues

More than 3.5 billion people globally suffer from the main oral diseases. These conditions combined have an estimated global prevalence of 45%—higher than any other non-communicable disease. 1 A major barrier to improving this situation is our approach to oral health.

The prevailing mindset is that oral health is synonymous with dentistry and that poor oral health has little impact on personal and societal health and wellbeing. We need to shift away from the idea that the prevention and control of certain oral diseases equates to overall oral health and instead move to a broader and more inclusive understanding. Expanded definitions of oral health from the World Health Organization and FDI World Dental Federation are transformational and can help realise a model for sustainable oral health put forward by the US National Academy of Medicine. 2 3 The academy proposes that oral health is influenced by a wide range of biological, psychosocial, and spiritual perspectives and external social, economic, and environmental factors. 4 This new narrative takes our understanding of oral health beyond the confines of disease and positions it in terms of personal confidence, wellbeing, and arising from and contributing to healthy societies more broadly. This narrative can herald a sea change for action in practice.

WHO recognises that oral health enables people to perform essential functions. 5 Orofacial structures are central to breathing and speaking. Oral health is linked to diet quality and adequate fluid intake which influences a person’s microbiome and their gut health. This is also important to our understanding of the gut-brain axis and the implications for mental health. Smiling and conveying a range of emotions through facial expressions is central to wellbeing and the ability to socialise and work. The mouth is central to our senses of smell, taste, and touch, which allows us to connect to our environment. The craniofacial complex is an integral part of the musculoskeletal system with implications for balance, gait, and mobility. In short, good oral health equates with wellbeing on a personal level.

Oral health is everyone’s job. Improving it will require an expanded oral health workforce that should include physicians, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, social workers, dietitians, community health workers, speech language pathologists, and other health providers, as well as non-traditional providers such as civic and religious leaders and teachers. 6 Oral health is already embedded in the universal health coverage agenda. Strengthening and scaling up oral health education and training as part of universal health coverage would enable an enlarged oral health workforce to integrate new knowledge, skills, and attitudes for oral health into their practice and daily routines. 7 In this way oral health could be monitored and maintained over the life course with a focus on patient centred concerns and outcomes. 8 This pivot would increase “oral health touch points” with children and families at all income levels, for example, for early detection of oral cancers and tobacco and alcohol interventions for patients at high risk.

Taking action on the social determinants of oral health inequity is at the heart of radical action to end the neglect of oral health. 9 Poor oral health disproportionately affects low income and other marginalised members of societies. Hierarchies of power, money, and resource distribution for oral health services continue to reinforce inequities, including through the continued biomedical dental approach, which both directly and indirectly influence oral health outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged people. 10 Ensuring oral health for all requires an approach involving the whole of government and society, including fixing broken food systems whose marketing, advertising, and sale of products contribute to poor oral health. 5 Actions could include implementing health taxes, particularly taxation of food and beverages with high free sugars content, and avoiding sponsorship by related companies for public and sports events. 3 Done right, oral health can play a major role in creating healthy societies. 11

Not commissioned, not externally peer reviewed.

The authors have no interests to declare.

- Bernabe E ,

- Marcenes W ,

- Hernandez CR ,

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators

- ↵ World Health Organization. Draft global strategy on oral health. 2022. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75_10Add1-en.pdf

- Williams DM ,

- Kleinman DV ,

- Vujicic M ,

- ↵ World Health Organization. Draft global oral health action plan (2023-2030). https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/mnd/oral-health/eb152-draft-global-oral-health-action-plan-2023-2030-en.pdf

- ↵ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2023. Sharing and exchanging ideas and experiences on community-engaged approaches to oral health: proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK600406 doi: 10.17226/27100

- ↵ World Health Organization. Global competency framework for universal health coverage. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352710/9789240034686-eng.pdf

- Riordain RN ,

- Mashhadani SSAA ,

- Allison P ,

- ↵ Public Health England. Inequalities in oral health in England. 19 March 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6051f994d3bf7f0453f7b9a9/Inequalities_in_oral_health_in_England.pdf

- Bestman A ,

- Srivastava S ,

- Yangchen S ,

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih…turning discovery into health ®.

Research for Healthy Living

Oral Health

In the early part of the 20th century, it was common for women and men to lose many teeth as they aged, leaving them to rely on dentures. That story began to change dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s, when NIH scientists showed that the rate of tooth decay fell more than 60 percent in children who drank fluoridated water. This discovery laid the foundation for a major component of modern dental health.

Today, research on oral health extends far beyond teeth. NIH researchers consider the mouth an expansive living laboratory to understand infections, cancer, and even healthy development processes. For example, we know that oral tissues and fluids, which are home to about 600 unique microbial species, can have remarkable protective roles against infection and possibly other conditions.

NIH research on oral health is working to understand and manipulate the body’s innate ability to repair and regenerate damaged or diseased tissues. These approaches will guide prevention and treatment of health problems not only in teeth and in the mouth, but also in other organs and tissues.

Optimal health for women and men

Certain health conditions are more common in women than in men, such as osteoporosis, depression, and autoimmune diseases. Others are more common in males, such as autism and color blindness. And there are those conditions that affect women and men differently, such as heart disease. While chest pain is common to both women and men suffering a heart attack, women may experience other symptoms such as nausea, back or neck pain, and fatigue, which they may not link to problems of the heart. NIH researchers are studying these differences, toward providing personalized care for individuals. The sexes can also have very different responses to even very common drugs like aspirin. So, NIH research ensures that females, including pregnant women when it is safe to do so, are included in sufficient numbers in clinical trials that test new medicines. Currently, slightly more than half of clinical trial participants are women.

« Previous: Arthritis Next: Vision »

This page last reviewed on November 16, 2023

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Adult health

Oral health: A window to your overall health

Your oral health is more important than you might realize. Learn how the health of your mouth, teeth and gums can affect your general health.

Did you know that your oral health offers clues about your overall health? Did you know that problems in the mouth can affect the rest of the body? Protect yourself by learning more about the link between your oral health and overall health.

What's the link between oral health and overall health?

Like other areas of the body, the mouth is full of germs. Those germs are mostly harmless. But the mouth is the entry to the digestive tract. That's the long tube of organs from the mouth to the anus that food travels through. The mouth also is the entry to the organs that allow breathing, called the respiratory tracts. So sometimes germs in the mouth can lead to disease throughout the body.

Most often the body's defenses and good oral care keep germs under control. Good oral care includes daily brushing and flossing. Without good oral hygiene, germs can reach levels that might lead to infections, such as tooth decay and gum disease.

Also, certain medicines can lower the flow of spit, called saliva. Those medicines include decongestants, antihistamines, painkillers, water pills and antidepressants. Saliva washes away food and keeps the acids germs make in the mouth in balance. This helps keep germs from spreading and causing disease.

Oral germs and oral swelling and irritation, called inflammation, are linked to a severe form of gum disease, called periodontitis. Studies suggest that these germs and inflammation might play a role in some diseases. And certain diseases, such as diabetes and HIV/AIDS, can lower the body's ability to fight infection. That can make oral health problems worse.

What conditions can be linked to oral health?

Your oral health might play a part in conditions such as:

- Endocarditis. This is an infection of the inner lining of the heart chambers or valves, called endocardium. It most often happens when germs from another part of the body, such as the mouth, spread through the blood and attach to certain areas in the heart. Infection of the endocardium is rare. But it can be fatal.

- Cardiovascular disease. Some research suggests that heart disease, clogged arteries and stroke might be linked to the inflammation and infections that oral germs can cause.

- Pregnancy and birth complications. Gum disease called periodontitis has been linked to premature birth and low birth weight.

- Pneumonia. Certain germs in the mouth can go into the lungs. This may cause pneumonia and other respiratory diseases.

Certain health conditions also might affect oral health, including:

Diabetes. Diabetes makes the body less able to fight infection. So diabetes can put the gums at risk. Gum disease seems to happen more often and be more serious in people who have diabetes.

Research shows that people who have gum disease have a harder time controlling their blood sugar levels. Regular dental care can improve diabetes control.

- HIV/AIDS. Oral problems, such as painful mouth sores called mucosal lesions, are common in people who have HIV/AIDS.

- Cancer. A number of cancers have been linked to gum disease. These include cancers of the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, lung, breast, prostate gland and uterus.

- Alzheimer's disease. As Alzheimer's disease gets worse, oral health also tends to get worse.

Other conditions that might be linked to oral health include eating disorders, rheumatoid arthritis and an immune system condition that causes dry mouth called Sjogren's syndrome.

Tell your dentist about the medicines you take. And make sure your dentist knows about any changes in your overall health. This includes recent illnesses or ongoing conditions you may have, such as diabetes.

How can I protect my oral health?

To protect your oral health, take care of your mouth every day.

- Brush your teeth at least twice a day for two minutes each time. Use a brush with soft bristles and fluoride toothpaste. Brush your tongue too.

- Clean between your teeth daily with floss, a water flosser or other products made for that purpose.

- Eat a healthy diet and limit sugary food and drinks.

- Replace your toothbrush every 3 to 4 months. Do it sooner if bristles are worn or flare out.

- See a dentist at least once a year for checkups and cleanings. Your dentist may suggest visits or cleanings more often, depending on your situation. You might be sent to a gum specialist, called a periodontist, if your gums need more care.

- Don't use tobacco.

Contact your dentist right away if you notice any oral health problems. Taking care of your oral health protects your overall health.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Gross EL. Oral and systemic health. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 1, 2024.

- Oral health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health. Accessed Feb. 1, 2024.

- Gill SA, et al. Integrating oral health into health professions school curricula. Medical Education Online. 2022; doi:10.1080/10872981.2022.2090308.

- Mark AM. For the patient: Caring for your gums. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2023; doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2023.09.012.

- Tonelli A, et al. The oral microbiome and the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2023; doi:10.1038/s41569-022-00825-3.

- Gum disease and other diseases. The American Academy of Periodontology. https://www.perio.org/for-patients/gum-disease-information/gum-disease-and-other-diseases/. Accessed Feb 1, 2024.

- Gum disease prevention. The American Academy of Periodontology. https://www.perio.org/for-patients/gum-disease-information/gum-disease-prevention/. Accessed Feb. 1, 2024.

- Oral health topics: Toothbrushes. American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/toothbrushes. Accessed Feb. 1, 2024.

- Issrani R, et al. Exploring the mechanisms and association between oral microflora and systemic diseases. Diagnostics. 2022; doi:10.3390/diagnostics12112800.

- HIV/AIDS & oral health. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/hiv-aids. Accessed Feb. 1, 2024.

- Dental floss vs. water flosser

- Dry mouth relief

- Sensitive teeth

- When to brush your teeth

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Oral health A window to your overall health

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Dental Care Among Adults Age 65 and Older: United States, 2022

NCHS Data Brief No. 500, April 2024

PDF Version (486 KB)

Robin A. Cohen, Ph.D., and Lauren Bottoms-McClain, M.P.H.

- Key findings

Among adults age 65 and older, dental visits in the past 12 months varied by sex, age group, and race and Hispanic origin.

Among adults age 65 and older, dental visits increased with increasing family income and increasing education level., dental visits among adults age 65 and older were higher among those with dental coverage., the percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit was lower among those in fair or poor health and those with diabetes or heart disease., definitions, data source and methods, about the authors, suggested citation.

Data from the National Health Interview Survey

- In 2022, 63.7% of adults age 65 and older had a dental visit in the past 12 months, and women (64.9%) were more likely than men (62.3%) to have had a dental visit.

- Among older adults, dental visits generally increased with increasing family income.

- Dental visits were higher among older adults with dental coverage (69.6%) compared with those without dental coverage (56.4%).

- Adults in fair or poor health and those with diabetes or heart disease were less likely to have had a dental visit compared with those without these conditions.

Oral health is associated with overall health, especially in older adults (age 65 and older). Chronic conditions in older adults may affect oral health, and poor oral health may increase the risk of certain chronic conditions ( 1–3 ). Poor oral health has also been associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk ( 4 ). Several factors, including chronic conditions, health status, race, and income have been associated with reduced dental care use among older adults ( 5–9 ). This report describes the percentage of older adults who had a dental visit in the past 12 months by selected sociodemographic characteristics and chronic conditions using the 2022 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

Keywords : oral health, chronic conditions , National Health Interview Survey

- In 2022, 63.7% of adults age 65 and older had a dental visit in the past 12 months ( Figure 1 , Table 1 ).

- Men (62.3%) were less likely than women (64.9%) to have had a dental visit.

- The percentage of older adults who had a dental visit decreased from 65.4% among those ages 65–74 and 63.6% among those ages 75–84 to 53.3% among those age 85 and older.

- The percentage of older adults who had a dental visit was highest among White non-Hispanic (subsequently, White) adults (68.1%) compared with Asian non-Hispanic (subsequently, Asian) adults (51.8%), Black non-Hispanic (subsequently, Black) adults (53.4%), other and multiple-race non-Hispanic (subsequently, other and multiple race) adults (48.8%), and Hispanic adults (48.0%). No other significant differences by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by sex, age group, and race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2022

Data table for Figure 1. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by sex, age group, and race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2022

1 People of Hispanic origin may be of any race. NOTES: Estimates are based on responses to the question, “About how long has it been since you last had a dental examination or cleaning?” A response of “within the past year (anytime less than 12 months ago)” was considered as having a dental visit in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Adults categorized as Asian non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, or White non-Hispanic indicated one race only. SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2022.

- In 2022, the percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months generally increased with increasing income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL), ranging from 35.3% among those with incomes less than 100% FPL to 80.5% among those with incomes greater than 400% FPL ( Figure 2 , Table 2 ).

- The percentage of older adults who had a dental visit increased with increasing education level, from 33.3% among those with less than a high school diploma to 82.0% among those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Figure 2. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by family income level and education level: United States, 2022

Data table for Figure 2. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by family income level and education level: United States, 2022

NOTES: Family income is based on a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). Estimates are based on responses to the question, “About how long has it been since you last had a dental examination or cleaning?” A response of “within the past year (anytime less than 12 months ago)” was considered as having a dental visit in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2022.

- In 2022, among adults age 65 and older, those with dental coverage were more likely to have had a dental visit in the past 12 months (69.6%) compared with those without dental coverage (56.4%) ( Figure 3 , Table 3 ).

Figure 3. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by dental coverage status: United States, 2022

Data table for Figure 3. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by dental coverage status: United States, 2022

NOTES: Estimates are based on responses to the question, “About how long has it been since you last had a dental examination or cleaning?” A response of “within the past year (anytime less than 12 months ago)” was considered as having a dental visit in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2022.

- In 2022, adults age 65 and older with fair or poor health (44.5%) were less likely than those in excellent, very good, or good health (69.5%) to have had a dental visit in the past 12 months ( Figure 4 , Table 4 ).

- Older adults with diabetes (55.1%) were less likely than those without diabetes (65.9%) to have had a dental visit.

- Older adults with heart disease (58.7%) were less likely than those without heart disease (64.7%) to have had a dental visit.

Figure 4. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by selected health factors: United States, 2022

Data table for Figure 4. Percentage of adults age 65 and older who had a dental visit in the past 12 months, by selected health factors: United States, 2022

NOTES: Estimates are based on responses to the question, “About how long has it been since you last had a dental examination or cleaning?” A response of “within the past year (anytime less than 12 months ago)” was considered as having had a dental visit in the past 12 months. Estimates are based on household interviews of a sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2022.

In 2022, 63.7% of U.S. adults age 65 and older had a dental visit in the past 12 months. Women, White adults, and adults ages 65–74 and 75–84 were more likely to have had a dental visit than their counterparts. Dental visits increased with increasing family income and education level. Also, older adults with dental coverage were more likely to have had a dental visit than those without dental coverage. Older adults with diabetes, heart disease, or those in fair or poor health were less likely to have had a dental visit than their counterparts. A previous report on dental care among older adults using the 2017 NHIS showed similar percentages of dental care use between men and women and decreasing visits with increasing age ( 10 ). However, it is important to note that NHIS was resigned in 2019 and the question wording for dental care was slightly changed, so estimates from NHIS data before 2019 may not be consistent with those from 2019 and later ( 10 , 11 ).

Dental visit in the past 12 months : Estimates are based on responses to the question, “About how long has it been since you last had a dental examination or cleaning?” A response of “within the past year (anytime less than 12 months ago)” was considered as having had a dental visit in the past 12 months. NHIS did not collect data on edentulism (toothlessness) in 2022, so older adults who do not have teeth are included in this measure.

Dental coverage : Adults were considered to have dental coverage if, at the time of interview, they had coverage through either a single-service plan, a private health insurance plan, or a Medicare Advantage plan. Adults covered by Medicaid living in a state where Medicaid provides comprehensive dental coverage were also considered to have dental coverage.

Family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level : Calculated from the family’s income in the previous calendar year and family size using the U.S. Census Bureau’s poverty thresholds ( 12 ). The 2022 NHIS imputed income file was used to create the poverty levels ( 13 ).

Race and Hispanic origin : Adults categorized as Hispanic may be any race or combination of races. Adults categorized as non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic White indicated one race only. Other and multiple races includes those who did not identify as Asian, Black, Hispanic, or White or who identified as more than one race. Analyses were limited to the race and Hispanic-origin groups for which data were reliable and had a large enough sample to make group comparisons.

This analysis was based on the 2022 NHIS. Estimates were based on a sample of 14,020 adults age 65 and older. NHIS is a nationally representative household survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. It is conducted continuously throughout the year by the National Center for Health Statistics. Interviews are typically conducted in respondents’ homes, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, interviewing procedures were disrupted, and 55.7% of the 2022 Sample Adult interviews were conducted at least partially by telephone ( 14 ). For more information about the NHIS, visit: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm .

Point estimates and their corresponding variances were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN software ( 15 ) to account for the complex sample design of NHIS. Differences between percentages were evaluated using two-sided significance t tests at the 0.05 level. Test for trends were evaluated using logistic regression. All estimates in this report met National Center for Health Statistics standards of reliability ( 16 ).

Robin A. Cohen and Lauren Bottoms-McClain are with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Interview Statistics.

- Leung KC, Chu CH. Dental care for older adults . Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1):214. 2022.

- Singhal A, Alofi A, Garcia RI, Sabik LM. Medicaid adult dental benefits and oral health of low-income older adults . J Am Dent Assoc 152(7):551–9.

- Coll PP, Lindsay A, Meng J, Gopalakrishna A, Raghavendra S, Bysani P, O’Brien D. The prevention of infections in older adults: Oral health. J Am Geriatr Soc 68(2):411–6. 2020.

- Van Dyke TE, Kholy KE, Ishai A, Takx RAP, Mezue K, Abohashem SM, et al. Inflammation of the periodontium associates with risk of future cardiovascular events . J Periodontol 92(3):348–58.

- Badr F, Sabbah W. Inequalities in untreated root caries and affordability of dental services among older American adults . Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(22):8523. 2020.

- Deraz O, Rangé H, Boutouyrie P, Chatzopoulou E, Asselin A, Guibout C, et al. Oral condition and incident coronary heart disease: A clustering analysis . J Dent Res 101(5):526–33. 2022.

- Borrell LN, Reynolds JC, Fleming E, Shah PD. Access to dental insurance and oral health inequities in the United States . Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 51(4):615–20. 2023.

- Sahab L, Sabbah W. Is the inability to afford dental care associated with untreated dental caries in adults? Community Dent Health 39(2):113–7. 2022.

- Vu GT, Little BB, Esterhay RJ, Jennings JA, Creel L, Gettleman L. Oral health-related quality of life in US adults with type 2 diabetes . J Public Health Dent 82(1):79–87. 2022.

- Kramarow EA. Dental care among adults aged 65 and over, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 337 . Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: 2019 survey description . 2020.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty thresholds .

- National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple imputation of family income in 2022 National Health Interview Survey: Methods . 2023.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: 2022 survey description . 2023.

- RTI International. SUDAAN (Release 11.0.3) [computer software]. 2018.

- Parker JD, Talih M, Malec DJ, Beresovsky B, Carroll M, Gonzalez JF Jr., et al. National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2(175). 2017.

Cohen RA, Bottoms-McClain L. Dental care among adults age 65 and older: United States, 2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 500. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc/151928 .

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

Division of Health Interview Statistics

Stephen J. Blumberg, Ph.D., Director Anjel Vahratian, Ph.D., M.P.H., Associate Director for Science

- Get E-mail Updates

- Data Visualization Gallery

- NHIS Early Release Program

- MMWR QuickStats

- Government Printing Office Bookstore

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Oral Health Policy and Research Capacity: Perspectives From Dental Schools in Africa

Affiliations.

- 1 Center for Integrative Global Oral Health, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- 2 Department of Oral Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Avondale, Harare, Zimbabwe.

- 3 Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- 4 Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- 5 Department of Community Dentistry and Periodontology, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt, Porty Harcourt, Nigeria.

- 6 Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Bayero University, Kano/Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Tarauni, Kano, Nigeria.

- 7 Department of preventive and Community Dentistry, School of Dentistry, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda.

- 8 Population Studies Center (PSC) and Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- 9 Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

- 10 Department of Public Health, Intercountry Centre for Oral Health (ICOH) for Africa, Jos Plateau State, Nigeria.

- 11 Department of Preventive Dentistry, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Idi-araba, Lagos, Nigeria.

- 12 Intercountry Center for Oral Health (ICOH) for Africa, Jos Plateau State, Nigeria.

- 13 Department of Preventive Dentistry, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Idi Araba, Lagos, Nigeria.

- 14 NCDs management team, WHO Regional Office for Africa, Brazzaville, Congo.

- 15 Center for Integrative Global Oral Health, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 38677971

- DOI: 10.1016/j.identj.2024.01.020

Introduction and aims: The prioritisation of oral health in all health policies in the WHO African region is gaining momentum. Dental schools in this region are key stakeholders in informing the development and subsequent downstream implementation and monitoring of these policies. The objectives of our study are to determine how dental schools contribute to oral health policies (OHPs) in this region, to identify the barriers to and facilitators for engaging with other local stakeholders, and to understand their capacity to respond to population and public health needs.

Methods: We developed a needs assessment survey, including quantitative and qualitative questions. The survey was developed electronically in Qualtrics and distributed by email in February 2023 to the deans or other designees at dental schools in the WHO African region. Data were analysed in SAS version 9.4 and ATLAS.ti.

Results: The capacity for dental schools to respond to population and public health needs varied. Most schools have postgraduate programs to train the next generation of researchers. However, these programs have limitations that may hinder the students from achieving the necessary skills and training. A majority (75%) of respondents were aware of the existence of national OHPs and encountered a myriad of challenges when engaging with them, including a lack of coordination with other stakeholders, resources, and oral health professionals, and the low priority given to oral health. Their strengths as technical experts and researchers was a common facilitator for engaging with OHPs.

Conclusion: Dental schools in the region face common challenges and facilitators in engaging in the OHP process. There were several school-specific research and training capacities that enabled them to respond to population and public health needs. Overall, shared challenges and facilitators can inform stakeholder dialogues at a national and subnational level and help develop tailored solutions for enhancing the oral health policy pipeline.

Keywords: Barrier; Facilitator; Oral health; Policy; Research; WHO African region.

Copyright © 2024. Published by Elsevier Inc.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee for Monitoring the Nation's Changing Needs for Biomedical, Behavioral, and Clinical Personnel. Advancing the Nation's Health Needs: NIH Research Training Programs. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2005.

Advancing the Nation's Health Needs: NIH Research Training Programs.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

5 Oral Health Research

Although dentistry is often thought of in terms of professional practice, it is also a science that depends on researchers to develop new and better dental technologies and, through the training of dental practitioners, to bring those technologies to the general public. But the profession is now in jeopardy, since the need for dental school faculty to conduct research and to educate dental students is acute. Over the past decade, several hundred faculty positions in dental schools have gone unfilled each year. While not all of them would be filled by researchers, it is to the profession's advantage—as it is in other sciences—to have as many research-trained Ph.D.s or D.D.S./Ph.D.s as possible in these positions. The shortage of research staff in universities carries over to the industrial and governmental sectors as well, where a significant amount of dental research is conducted.

The reasons for this shortage are many. To cite just one, a culture exists within dental schools that values technical training and private practice over research, resulting in deficiencies in the support mechanisms for whoever does do research. The following sections describe the nature and scope of the problem.

- THE SHORTAGE OF DENTAL SCIENTISTS

In 2001 the American Dental Association issued a report, Future of Dentistry , which outlined many of the issues facing the dental profession including what is now called a crisis in dental education. This crisis may be more aptly termed a dental school faculty shortage that has become acute because few individuals choose academics and research as a career goal. In the late 1990s there were nearly 400 open faculty positions, but the estimate for 2002 was 373. This reduction in the number of unfilled positions has come mainly from the elimination of those positions (because of dental school budget cuts) rather than from faculty hires.

Figure 5-1 gives a 10-year history of vacant full-time faculty positions in U.S. dental schools. Given that the level has remained about constant over the past 5 or 6 years, the number is unlikely to decline in the near future. While the number of unfilled full-time positions is approximately 275, this should not be interpreted as the number of research faculty needed, as some of these positions are for clinical faculty. In Table 5-1 , which shows the distribution of vacant positions by primary activity, 45 of them are in basic sciences and research. But in addition, some of the 194 clinical positions would be research oriented.

Unfilled full-time positions on dental school faculties, 1992–2002. SOURCE: American Dental Education Association.

Vacant Faculty Positions in Dental Schools, 2001–2002 .

While the shortage is critical across all types of appointments, the job of filling research positions is particularly difficult because there is no pool of temporary or part-time employees—as is the case for the clinical positions, which can be filled by practicing dentists. Dental faculty are simply not trained to be researchers, and many of them may not have the interest or ability to explore new areas of knowledge. Clinicians who teach students to perform dental care are, without a doubt, critical to the mission of dental schools but are not discussed here.

This recruitment problem does not tell the whole story about the number of scientists needed in dental education for the next decade. A possibly more critical situation is the retention of current faculty. According to data from the American Dental Education Association's 2001–2002 Survey of Dental Schools, 1,011 faculty members, or 9 percent, vacated their positions in 2001–2002. 1 This level was about twice that of the previous academic year. In 2001–2002, 53 percent of faculty members left an academic position to go into private practice, an increase of 18 percent over the preceding year. Possible reasons for the shifts in 2001–2002 may be retirement, moving to other schools, and the downturn in the economy.

Institutional budgetary limitations are partly responsible for the recruitment and retention of dental faculty—in the past 10 years, faculty salaries have increased by about 25 to 30 percent, while income in private practice has gone up 78 percent. 2 An important related financial issue is the debt incurred by dental students during their studies. Among students who entered dental school in 1998, about 60 percent had no education debt. Those who reported debt had an average burden of $25,300. Hence, a rationale might be that a pool of applicants with little or no education debt would be more at liberty to select a career path aimed at pursuing interests, rather than immediately generating income for debt service. However, of those graduating from dental school in 2002, 29 percent reported debt levels of $100,000 to $149,999. 3 Debt levels higher than $150,000 were reported by 29 percent of graduates. The average debt of all students upon graduation (from both public and private dental schools) was $107,500 (this average includes debt-free students). The average debt of those students who had at least some debt was $122,500. In general, their debt is higher than in any other profession, including medicine, because they are required to purchase instruments used in dental school. The impact of debt on career path is substantiated by the finding that nearly 24 percent of dental school seniors indicate debt as a factor influencing career plans. Further, as debt levels increase, a progressively higher percentage of seniors with the higher debt levels opt to immediately enter private practice.

Perhaps the most significant factor driving the low interest in research among dentists is the prospect of a very lucrative career in private practice. General practitioners can expect an annual income of nearly $150,000, with specialists earning over $200,000, and there is no indication that these figures will decline in the future even with significant advances in oral health care. Thus many students who may be interested in research elect the higher-paid and, from their point of view, more secure careers in clinical practice.

The aging of the dental school faculty will only make the shortages of the past decade more of a problem in the future. The average age of faculty members in 2001 was 49.6 years, and 20 percent of the faculty were over the age of 60. Because there is little difference in the average age of the basic science/research faculty and the clinical faculty, the projections of about 1,000 retirements in the over-60 age group in the next 10 years would mean a reduction in the basic science and research faculty of about 200. The fact that few associate professors are following closely behind these senior faculty members means that the pipeline has many gaps and that an even greater need for researchers will exist over the next 10 years. The shortage of senior faculty will also create a period during which junior faculty have few mentors to assist them in the activities necessary for tenure and promotion.

In the context of the faculty shortage in dentistry, it is important to realize that not all research faculty in dental schools need be dentists. While clinicians trained as dentists are useful in answering clinical questions and are fundamental to clinical research, nondentist basic scientists trained to the highest standards are also an important part of the faculty mix. Although dental schools should have a mix of basic and clinical scientists to achieve the institutions' and the nation's research goals, few doctorates trained in the basic biomedical sciences have considered academic careers in a dental school. While some training may be necessary to make this adjustment in career goals, the benefit to the dental and biomedical professions would be significant. A complicating factor, however, is that some administrators in dental schools might not be willing to accept the qualifications of these basic scientists, even with the necessary training.

- POTENTIAL POOL OF DENTAL RESEARCHERS

The size and quality of the national applicant pool for U.S. dental schools merit scrutiny. Because this pool represents a large and relatively robust population of people who have an interest in oral health and are willing to further their formal education through an extensive training experience, a large proportion of the next generation of oral health researchers will likely be drawn from this group. Additional scientists may come from abroad or from among those practitioners who gravitate to oral health research as a consequence of their interest in its scientific challenges.

There are 56 dental schools in 34 states and Puerto Rico, enrolling 17,487 dental students and 5,266 dental residents in 2001. There were 4,448 first-year dental students, selected from a total applicant pool of 7,538. 4 The current ratio of applicants to first-year enrollment for dental school is 1 to 68. Among applicants to dental school in 2001–2002, 83.9 percent possessed baccalaureate degrees, 2.5 percent had master's degrees, and 0.1 percent had Ph.D. degrees, suggesting that preexisting research training or experience for this applicant pool is negligible. Clearly, if education in biomedical research is to be offered, it needs either to be a part of professional school study or provided as a postgraduate experience.

The predental grade point average for the year 2000 entering class was 3.35 overall and 3.25 in the sciences. 5 Dental Aptitude Test scores for the entering class of 2001–2002 were 18.65 (academic average) and 18.36 (science average), both on a 30-point standard scale. 6 Thus, given the number of slots available each year in U.S. dental schools, the applicant pool's academic quality, though above average, was not overwhelming.

A key question is whether a subset of individuals at the high end of the academic distribution can be drawn from the national pool and attracted to careers in biomedical research. Given both the size of this group and its mean GPA of 3.25 in the sciences, the existence of a sizable subset of academic high performers seems plausible, yet the percentage of graduates interested in teaching, research, or administration is small and declining. Few students entering dental school are aware of a career path that includes oral health research, and even fewer consider this option as they complete their training. Interest in research dropped from about 1.3 percent in 1980 to 0.5 percent in 2002. 7 This means that only about 20 of the nearly 4,000 dental school graduates each year consider a career in dental research.

The reasons for this low interest, as noted earlier, include the prospects of a high income in dental practice; the accumulated student debt; and a culture in many dental schools, especially among the clinical staff, that values the technical aspects of dentistry and often marginalizes research. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has two grant programs that support the infrastructure in dental schools: the R24 for planning research facilities and infrastructure and the R25 for planning curriculum structure. It is generally believed that a higher percentage of students, although small, are interested in dental research earlier as opposed to later in their education; it might be possible to influence dental students later in their education by integrating research into professional training through the NIH grant programs. However, most dental school applicants are interested in becoming dentists, not biomedical researchers. This intention is presumably based on applicants' general understanding of what dentists do. Inasmuch as 92.7 percent of professionally active dentists are engaged in private practice, with 92.1 percent of that number holding an equity share in a practice, 8 it seems reasonable that most dental school applicants aspire to a career as a small-business person rather than as a biomedical scientist. Yet it is still from such a pool that the future biomedical research scientists in this field are likely to come. In other words, biomedical researchers in the oral health sciences start out wanting to be practicing dentists; but they apparently undergo a significant shift in career plans and professional identity sometime during either dental school or specialty training, usually under the influence of a mentor or because of some other significant academic experience. What dental schools can do to foster such a shift is an important question.

Each year competition is great for the highest academic performers graduating from dental school. The most effective at siphoning off the best are the nine specialties in dentistry: oral and maxillofacial surgery, orthodontics, periodontics, endodontics, pediatric dentistry, prosthodontics, oral and maxillofacial pathology, oral and maxillofacial radiology, and public health dentistry. For 2001–2002, 1,264 students enrolled in these specialty programs. Although the number of applications for these positions is reported as 43,612, this figure is misleading because “applications” refers to the cumulative number of applicants to all programs and represents a duplicated count. 9 Because of the inordinate length of some specialty training programs—anywhere from 2 to 7 years after dental school—some residents may exclude themselves from the additional training needed to become a biomedical scientist. On the other hand, departmentally based dental schools are, arguably, run by research-oriented dental specialists. Thus, while there are positions for general dentists in dental schools, leadership positions are often held by research-oriented specialists. The preferred model for training biomedical research scientists in the oral health sciences is to have dental specialists go on to research training, usually by studying for a Ph.D. Hence, the approximately 1,200 specialty students can be seen as the potential pool for the recruitment of future scientists—though a relatively small percentage of this number are actually attracted by the prospect of actually doing so. In recognition of this possibility, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) has tried several programs leading to advanced research training (usually through the vehicle of a Ph.D.) in combination with either the dental school curriculum or clinical specialty training.

One initiative that was instituted by NIDCR, in response to a recommendation from the National Research Council's study of the National Research Service Award (NRSA) program, was a Dental Scientist Training Program (DSTP)—a dual-degree program leading to a D.D.S. and a Ph.D. In 2001–2002, 11 institutions had NIH-supported DSTPs, with a total of about 30 students. There were another 10 institutions with D.D.S./Ph.D. programs that did not have NIH support. The applicant pool for the DSTPs is very strong, and more students could be accepted into them if funding were available. The curriculum sequence for the DSTP at many institutions is similar to that of the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP)—the first 2 years are spent in dental training, the next 2 to 3 years are devoted to research training for the Ph.D., and then students return to dental school for 2 or more years to complete their dental degrees.

One serious drawback to the DSTP is its funding mechanism. The MSTP students may receive support for up to 6 years under the NRSA requirements, and MSTP policy requires that every student be supported with stipends and total tuition for the entire period of dual degree. However, the DSTP student may only receive 5 years of support with the possibility of a sixth year under the T32 mechanism, and no full support requirement exists. This support usually applies during the Ph.D. portion of students' training and part of their dental training, but other sources must be found to support their studies for the rest of the program. Some institutions have used the K award mechanism to secure the needed funding. Consequently, students can complete the DSTP and still have debt. This program is new—only a few students have completed it—but graduates appear to be dedicated to research careers and are now in postdoctoral training.

Some insight comes from studying other training programs funded by NIDCR, given that this single institute funds the overwhelming majority of research training for oral health researchers. In fact, about 8.5 percent of the NIDCR budget in FY 2002 was spent on research training and career development 10 —approximately $20.4 million (total of both direct and indirect costs). 11 In 2002 NIDCR supported at least a dozen separate categories of research training and career development awards, including 157 NRSA grants and research career development awards. Further, for FY 2003, 50.6 percent of training grant proposals reviewed by NIDCR were funded (averaged over the individual awards). Though useful, these data do not in themselves provide much information concerning the actual number of persons currently in training through these various vehicles since some represent awards to individuals while others represent awards to institutions—each of the institutional awards providing funding for multiple individuals (and differing numbers of individuals per training program). Further, they provide even less information about the number of applicants to each program. Were such data available—such as the number of applicants for each training slot—they would be useful as a gauge of interest in training programs, and they would inform projections concerning the potential shortfall of biomedical research personnel relative to the nation's needs. Also they would help determine whether, from a national perspective, the number of applicants exceeds, matches, or falls short of the number of training slots available. A one-to-one match of applicants to available positions or, even more alarming, unfilled research training slots would not bode well either for the number of persons in the pipeline or, perhaps more significantly, for their quality.

In any case, although the number of individual awards may give one indication of the demand for training through institutional awards, this effect has never been quantified—in part because NIH grants are attributed to the principal investigator, not the individual trainee.

- RESOURCES FOR RESEARCH TRAINING

There is a need to systematically identify sources of collaborative funding for research training across government agencies and within the private sector. The goal of this effort is to facilitate communication and thereby expand the pool of funds that could be used for research training in fields related to oral health.

Although it provides the largest single source of all dental research training funds, the research training budget of NIDCR is limited and under financial pressure in the current economic climate. For example, in 2002 there were 31 NRSA grants, 70 research career development awards, and 48 K12 and K16 awards, for a total of 149 research training awards across the nation. The level of support in NIDCR for NRSA T32 and T35 grants was about 2.9 percent of its total budget, and for NRSA F31 grants the support was at 0.4 percent. This was about average for these awards across the NIH institutes. When considering the relatively large amount of research training support within other agencies of the government and the private sector, it becomes apparent that the possibility of augmenting NIDCR research training funds with other governmental and private-sector funds could markedly increase the total research training capacity for dental research in the United States.

Inspection of Tables 5-2 and 5-3 suggests that the research areas of concentration for FY 2002 could be linked to scientific research areas that are funded by other disciplines. For example, there are many research training programs across NIH and in other agencies of the government that fund the same or similar research disciplines being targeted by the NIDCR, such as microbiology, microbial pathogenesis, immunology, biotechnology, mammalian genetics, epithelial cell regulation, physiology, pharmacogenetics, molecular and cellular neurobiology, clinical trials and patient-oriented research, behavioral research, and population sciences. Dental researchers being trained in any of these NIDCR-funded research training programs could be co-funded or co-supported by other research training funds that are similarly targeted toward these research disciplines.

Research Areas of Research Career Development Awardees, Fiscal Year 2002.

Research Areas of Institutional National Research Service Award T32 Programs, Fiscal Year 2002.

An NIH policy could facilitate and encourage co-funding of research trainees. Also, a barrier that needs lifting is the tendency to discourage dentist scholars from applying for research training funds within these disciplines. If applicants other than physicians are eligible, dentists should also be eligible, while funds targeted specifically for physician research training would stay limited to physician applicants. With this broadening of the spectrum of research training sources to which dentist-researchers could apply, the opportunity for collaborative funding for research training in fields related to oral health would expand. Sources of research training funds could include various government agencies, foundations, universities, industrial organizations, and foreign governments.

Aside from the funding method used for the DSTP program, there are serious problems with the way NIH programs are now being administered. For example, there is a need for more dental-oriented clinical researchers, especially those involved in translational research; clinical studies, such as Phase II or case-control studies; randomized controlled trials, including hypothesis-driven NIH Phase III type trials and Food and Drug Administration Phase II- and III-type trials; and Phase IV studies of side effects and interactions with co-therapies. Researchers with the ability to participate in all of these types of clinical investigations are needed. Clinical researchers who can participate in high-level development and applications research, such as the engineering of products, also are needed. The K30 institutional grants are designed to do just this. However, most of these applications appear to come from medical schools and nondental institutions, and the emphasis is not on training dental researchers.

Finally, training in interdisciplinary and emerging fields is not now traditionally thought of as being within the dental research training profile. Dental research relies on or crosses other disciplinary areas (see the next section), but little support is given for training in these areas. This problem is partly one at NIH, where the tendency is not to support such training; but the educational institutions are also responsible, since they do not apply for T32 awards in interdisciplinary or emerging fields.

- NATIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE AWARD PROGRAM AND OTHER NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH PROGRAMS

In 2002, NIDCR funded 31 new, continuing, or noncompeting T32 training grants. These grants supported a total of 81 predoctoral students and 86 postdoctoral appointees. In addition, they provided support for 27 short-term projects under the T35 mechanism. Of the 31 funded T32 awards, 20 provided support for students in Ph.D. programs and the other 11 were for support of the DSTP. The 20 non-DSTPs supported about 50 students at the predoctoral level, and based on the statistics on vacant research positions in dental schools, these programs could eliminate any shortage in a few years. But many of the trainees do not view dental school and dental-oriented research as a career option. In terms of individual fellowship awards, there are 16 F30 awards for support of predoctoral students in dual D.D.S./ Ph.D. and D.M.D./Ph.D. programs, one F31 award for predoctoral support in a Ph.D. program, and nine postdoctoral fellowships. While the F30 award is designed to support training in an established dual-degree program for students who intend to be researchers, it is no guarantee that students will not pursue professional careers.

Individuals in the dental community have made extensive use of the K award program, securing 70 awards in 2002. A little over half of these awards were for clinical training through the K02, K08, K23, and K24 mechanisms. There are 30 awards that could be considered transitional training, and 20 are the new K22 awards. This level of participation in the K22 is unusually high, since there were only 93 K22 awards across all NIH institutes. Of all the fields of study the K awards seem to work well for the dental profession, since the mission-oriented research of the profession fits with the rigid structure of these awards.

One program at NIH that has not been widely used by dental professionals is loan repayment. In 2002 only six individuals with a D.D.S. participated in the clinical research loan repayment program, and no one with this degree applied to the program under the health disparity or disadvantaged-background features of the program. Considering the high level of debt that dentists have when they graduate from dental school, it seems this program would be attractive.

Even though many committees and working groups have addressed the issue of clinical research training, there remains a critical shortage of clinical scientists in dentistry, particularly to perform Phase II- and III-type trials. There are a few oral health scientists trained in epidemiology who could carry out these clinical trials, but epidemiology or public health training often does not include the skills needed to conduct clinical trials. The recommendation in the clinical sciences chapter of this report that addresses the need for physician training in this area should apply equally to the training of dental clinicians.

The issue of minority researcher training, and of the training of researchers in general to address the health of minorities, is as important in dentistry as it is in other fields. African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans make up only about 10 percent of all students enrolled in dental schools, reflecting a steady 10-year downward trend that could have a major impact on the dental health of minority populations. After a slight increase in enrollment through the mid-1990s, only 810 African Americans, 913 Hispanic Americans, and 99 Native Americans were enrolled in dental schools during the 1999–2000 academic year. Minorities are also underrepresented in private practices, with African Americans making up 2.2 percent of dentists, Hispanic Americans accounting for 2.8 percent, and Native Americans representing 0.2 percent. The second aspect of minority research is the training of investigators who have competence and commitment to investigate health care disparities among populations. A broad array of investigators is needed—people with skills in molecular epidemiology, clinical trials, and field studies and who have knowledge and interest in diseases that occur in populations that suffer from health care disparities.

While many programs exist at NIH to address the shortage of minority researchers, the success of these programs is unclear. And in light of the general shortage of dental school faculty, it is unlikely that any changes will take place without strong programs that are specifically targeted in this area.

The need for augmented research in oral health clearly exists. However, equally clear is the shortage of faculty to carry out the training and act in the interest of dental trainees in research. For this situation to improve, dental schools must place a higher priority on research and ensure that exposure to research is part of the curriculum. Unfortunately, recommendations in this regard are beyond the scope of this committee. However, some positive steps can be taken in existing programs to provide incentives to prospective trainees.

- RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 5-1: This committee recommends that NIDCR fund all required years of the D.D.S./Ph.D. program.