- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About How to Improve American Education

An international exam shows that American 15-year-olds are stagnant in reading and math. Teenagers told us what’s working and what’s not in the American education system.

By The Learning Network

Earlier this month, the Program for International Student Assessment announced that the performance of American teenagers in reading and math has been stagnant since 2000 . Other recent studies revealed that two-thirds of American children were not proficient readers , and that the achievement gap in reading between high and low performers is widening.

We asked students to weigh in on these findings and to tell us their suggestions for how they would improve the American education system.

Our prompt received nearly 300 comments. This was clearly a subject that many teenagers were passionate about. They offered a variety of suggestions on how they felt schools could be improved to better teach and prepare students for life after graduation.

While we usually highlight three of our most popular writing prompts in our Current Events Conversation , this week we are only rounding up comments for this one prompt so we can honor the many students who wrote in.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

Put less pressure on students.

One of the biggest flaws in the American education system is the amount of pressure that students have on them to do well in school, so they can get into a good college. Because students have this kind of pressure on them they purely focus on doing well rather than actually learning and taking something valuable away from what they are being taught.

— Jordan Brodsky, Danvers, MA

As a Freshman and someone who has a tough home life, I can agree that this is one of the main causes as to why I do poorly on some things in school. I have been frustrated about a lot that I am expected to learn in school because they expect us to learn so much information in such little time that we end up forgetting about half of it anyway. The expectations that I wish that my teachers and school have of me is that I am only human and that I make mistakes. Don’t make me feel even worse than I already am with telling me my low test scores and how poorly I’m doing in classes.

— Stephanie Cueva, King Of Prussia, PA

I stay up well after midnight every night working on homework because it is insanely difficult to balance school life, social life, and extracurriculars while making time for family traditions. While I don’t feel like making school easier is the one true solution to the stress students are placed under, I do feel like a transition to a year-round schedule would be a step in the right direction. That way, teachers won’t be pressured into stuffing a large amount of content into a small amount of time, and students won’t feel pressured to keep up with ungodly pacing.

— Jacob Jarrett, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

In my school, we don’t have the best things, there are holes in the walls, mice, and cockroaches everywhere. We also have a lot of stress so there is rarely time for us to study and prepare for our tests because we constantly have work to do and there isn’t time for us to relax and do the things that we enjoy. We sleep late and can’t ever focus, but yet that’s our fault and that we are doing something wrong. School has become a place where we just do work, stress, and repeat but there has been nothing changed. We can’t learn what we need to learn because we are constantly occupied with unnecessary work that just pulls us back.

— Theodore Loshi, Masterman School

As a student of an American educational center let me tell you, it is horrible. The books are out dated, the bathrooms are hideous, stress is ever prevalent, homework seems never ending, and worst of all, the seemingly impossible feat of balancing school life, social life, and family life is abominable. The only way you could fix it would be to lessen the load dumped on students and give us a break.

— Henry Alley, Hoggard High School, Wilmington NC

Use less technology in the classroom (…or more).

People my age have smaller vocabularies, and if they don’t know a word, they just quickly look it up online instead of learning and internalizing it. The same goes for facts and figures in other subjects; don’t know who someone was in history class? Just look ‘em up and read their bio. Don’t know how to balance a chemical equation? The internet knows. Can’t solve a math problem by hand? Just sneak out the phone calculator.

My largest grievance with technology and learning has more to do with the social and psychological aspects, though. We’ve decreased ability to meaningfully communicate, and we want everything — things, experiences, gratification — delivered to us at Amazon Prime speed. Interactions and experiences have become cheap and 2D because we see life through a screen.

— Grace Robertson, Hoggard High School Wilmington, NC

Kids now a days are always on technology because they are heavily dependent on it- for the purpose of entertainment and education. Instead of pondering or thinking for ourselves, our first instinct is to google and search for the answers without giving it any thought. This is a major factor in why I think American students tests scores haven’t been improving because no one wants to take time and think about questions, instead they want to find answers as fast as they can just so they can get the assignment/ project over with.

— Ema Thorakkal, Glenbard West HS IL

There needs to be a healthier balance between pen and paper work and internet work and that balance may not even be 50:50. I personally find myself growing as a student more when I am writing down my assignments and planning out my day on paper instead of relying on my phone for it. Students now are being taught from preschool about technology and that is damaging their growth and reading ability. In my opinion as well as many of my peers, a computer can never beat a book in terms of comprehension.

— Ethan, Pinkey, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Learning needs to be more interesting. Not many people like to study from their textbooks because there’s not much to interact with. I think that instead of studying from textbooks, more interactive activities should be used instead. Videos, websites, games, whatever might interest students more. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t use textbooks, I’m just saying that we should have a combination of both textbooks and technology to make learning more interesting in order for students to learn more.

— Vivina Dong, J. R. Masterman

Prepare students for real life.

At this point, it’s not even the grades I’m worried about. It feels like once we’ve graduated high school, we’ll be sent out into the world clueless and unprepared. I know many college students who have no idea what they’re doing, as though they left home to become an adult but don’t actually know how to be one.

The most I’ve gotten out of school so far was my Civics & Economics class, which hardly even touched what I’d actually need to know for the real world. I barely understand credit and they expect me to be perfectly fine living alone a year from now. We need to learn about real life, things that can actually benefit us. An art student isn’t going to use Biology and Trigonometry in life. Exams just seem so pointless in the long run. Why do we have to dedicate our high school lives studying equations we’ll never use? Why do exams focusing on pointless topics end up determining our entire future?

— Eliana D, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

I think that the American education system can be improved my allowing students to choose the classes that they wish to take or classes that are beneficial for their future. Students aren’t really learning things that can help them in the future such as basic reading and math.

— Skye Williams, Sarasota, Florida

I am frustrated about what I’m supposed to learn in school. Most of the time, I feel like what I’m learning will not help me in life. I am also frustrated about how my teachers teach me and what they expect from me. Often, teachers will give me information and expect me to memorize it for a test without teaching me any real application.

— Bella Perrotta, Kent Roosevelt High School

We divide school time as though the class itself is the appetizer and the homework is the main course. Students get into the habit of preparing exclusively for the homework, further separating the main ideas of school from the real world. At this point, homework is given out to prepare the students for … more homework, rather than helping students apply their knowledge to the real world.

— Daniel Capobianco, Danvers High School

Eliminate standardized tests.

Standardized testing should honestly be another word for stress. I know that I stress over every standardized test I have taken and so have most of my peers. I mean they are scary, it’s like when you take these tests you bring your No. 2 pencil and an impending fail.

— Brennan Stabler, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Personally, for me I think standardized tests have a negative impact on my education, taking test does not actually test my knowledge — instead it forces me to memorize facts that I will soon forget.

— Aleena Khan, Glenbard West HS Glen Ellyn, IL

Teachers will revolve their whole days on teaching a student how to do well on a standardized test, one that could potentially impact the final score a student receives. That is not learning. That is learning how to memorize and become a robot that regurgitates answers instead of explaining “Why?” or “How?” that answer was found. If we spent more time in school learning the answers to those types of questions, we would become a nation where students are humans instead of a number.

— Carter Osborn, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

In private school, students have smaller class sizes and more resources for field trips, computers, books, and lab equipment. They also get more “hand holding” to guarantee success, because parents who pay tuition expect results. In public school, the learning is up to you. You have to figure stuff out yourself, solve problems, and advocate for yourself. If you fail, nobody cares. It takes grit to do well. None of this is reflected in a standardized test score.

— William Hudson, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Give teachers more money and support.

I have always been told “Don’t be a teacher, they don’t get paid hardly anything.” or “How do you expect to live off of a teachers salary, don’t go into that profession.” As a young teen I am being told these things, the future generation of potential teachers are being constantly discouraged because of the money they would be getting paid. Education in Americans problems are very complicated, and there is not one big solution that can fix all of them at once, but little by little we can create a change.

— Lilly Smiley, Hoggard High School

We cannot expect our grades to improve when we give teachers a handicap with poor wages and low supplies. It doesn’t allow teachers to unleash their full potential for educating students. Alas, our government makes teachers work with their hands tied. No wonder so many teachers are quitting their jobs for better careers. Teachers will shape the rest of their students’ lives. But as of now, they can only do the bare minimum.

— Jeffery Austin, Hoggard High School

The answer to solving the American education crisis is simple. We need to put education back in the hands of the teachers. The politicians and the government needs to step back and let the people who actually know what they are doing and have spent a lifetime doing it decide how to teach. We wouldn’t let a lawyer perform heart surgery or construction workers do our taxes, so why let the people who win popularity contests run our education systems?

— Anders Olsen, Hoggard High School, Wilmington NC

Make lessons more engaging.

I’m someone who struggles when all the teacher does is say, “Go to page X” and asks you to read it. Simply reading something isn’t as effective for me as a teacher making it interactive, maybe giving a project out or something similar. A textbook doesn’t answer all my questions, but a qualified teacher that takes their time does. When I’m challenged by something, I can always ask a good teacher and I can expect an answer that makes sense to me. But having a teacher that just brushes off questions doesn’t help me. I’ve heard of teachers where all they do is show the class movies. At first, that sounds amazing, but you don’t learn anything that can benefit you on a test.

— Michael Huang, JR Masterman

I’ve struggled in many classes, as of right now it’s government. What is making this class difficult is that my teacher doesn’t really teach us anything, all he does is shows us videos and give us papers that we have to look through a textbook to find. The problem with this is that not everyone has this sort of learning style. Then it doesn’t help that the papers we do, we never go over so we don’t even know if the answers are right.

— S Weatherford, Kent Roosevelt, OH

The classes in which I succeed in most are the ones where the teachers are very funny. I find that I struggle more in classes where the teachers are very strict. I think this is because I love laughing. Two of my favorite teachers are very lenient and willing to follow the classes train of thought.

— Jonah Smith Posner, J.R. Masterman

Create better learning environments.

Whenever they are introduced to school at a young age, they are convinced by others that school is the last place they should want to be. Making school a more welcoming place for students could better help them be attentive and also be more open minded when walking down the halls of their own school, and eventually improve their test scores as well as their attitude while at school.

— Hart P., Bryant High School

Students today feel voiceless because they are punished when they criticize the school system and this is a problem because this allows the school to block out criticism that can be positive leaving it no room to grow. I hope that in the near future students can voice their opinion and one day change the school system for the better.

— Nico Spadavecchia, Glenbard West Highschool Glen Ellyn IL

The big thing that I have struggled with is the class sizes due to overcrowding. It has made it harder to be able to get individual help and be taught so I completely understand what was going on. Especially in math it builds on itself so if you don’t understand the first thing you learn your going to be very lost down the road. I would go to my math teacher in the morning and there would be 12 other kids there.

— Skyla Madison, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

The biggest issue facing our education system is our children’s lack of motivation. People don’t want to learn. Children hate school. We despise homework. We dislike studying. One of the largest indicators of a child’s success academically is whether or not they meet a third grade reading level by the third grade, but children are never encouraged to want to learn. There are a lot of potential remedies for the education system. Paying teachers more, giving schools more funding, removing distractions from the classroom. All of those things are good, but, at the end of the day, the solution is to fundamentally change the way in which we operate.

Support students’ families.

I say one of the biggest problems is the support of families and teachers. I have heard many success stories, and a common element of this story is the unwavering support from their family, teachers, supervisors, etc. Many people need support to be pushed to their full potential, because some people do not have the will power to do it on their own. So, if students lived in an environment where education was supported and encouraged; than their children would be more interested in improving and gaining more success in school, than enacting in other time wasting hobbies that will not help their future education.

— Melanie, Danvers

De-emphasize grades.

I wish that tests were graded based on how much effort you put it and not the grade itself. This would help students with stress and anxiety about tests and it would cause students to put more effort into their work. Anxiety around school has become such a dilemma that students are taking their own life from the stress around schoolwork. You are told that if you don’t make straight A’s your life is over and you won’t have a successful future.

— Lilah Pate, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

I personally think that there are many things wrong with the American education system. Everyone is so worried about grades and test scores. People believe that those are the only thing that represents a student. If you get a bad grade on something you start believing that you’re a bad student. GPA doesn’t measure a students’ intelligence or ability to learn. At young ages students stop wanting to come to school and learn. Standardized testing starts and students start to lose their creativity.

— Andrew Gonthier, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Praise for great teachers

Currently, I’m in a math class that changed my opinion of math. Math class just used to be a “meh” for me. But now, my teacher teachers in a way that is so educational and at the same time very amusing and phenomenal. I am proud to be in such a class and with such a teacher. She has changed the way I think about math it has definitely improve my math skills. Now, whenever I have math, I am so excited to learn new things!

— Paulie Sobol, J.R Masterman

At the moment, the one class that I really feel supported in is math. My math teachers Mrs. Siu and Ms. Kamiya are very encouraging of mistakes and always are willing to help me when I am struggling. We do lots of classwork and discussions and we have access to amazing online programs and technology. My teacher uses Software called OneNote and she does all the class notes on OneNote so that we can review the class material at home. Ms. Kamiya is very patient and is great at explaining things. Because they are so accepting of mistakes and confusion it makes me feel very comfortable and I am doing very well in math.

— Jayden Vance, J.R. Masterman

One of the classes that made learning easier for me was sixth-grade math. My teacher allowed us to talk to each other while we worked on math problems. Talking to the other students in my class helped me learn a lot quicker. We also didn’t work out of a textbook. I feel like it is harder for me to understand something if I just read it out of a textbook. Seventh-grade math also makes learning a lot easier for me. Just like in sixth-grade math, we get to talk to others while solving a problem. I like that when we don’t understand a question, our teacher walks us through it and helps us solve it.

— Grace Moan, J R Masterman

My 2nd grade class made learning easy because of the way my teacher would teach us. My teacher would give us a song we had to remember to learn nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, etc. which helped me remember their definitions until I could remember it without the song. She had little key things that helped us learn math because we all wanted to be on a harder key than each other. She also sang us our spelling words, and then the selling of that word from the song would help me remember it.

— Brycinea Stratton, J.R. Masterman

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

What Will It Take to Fix Public Education?

The last two presidents have introduced major education reform efforts. Are we making progress toward a better and more equitable education system? Yale Insights talked with former secretary of education John King, now president and CEO of the Education Trust, about the challenges that remain, and the impact of the Trump Administration.

- John B. King President and CEO, The Education Trust

This interview was conducted at the Yale Higher Education Leadership Summit , hosted by Yale SOM’s Chief Executive Leadership Institute on January 30, 2018.

On January 8, 2002, President George W. Bush traveled to Hamilton High School in Hamilton, Ohio, to sign the No Child Left Behind Act , a bipartisan bill (Senator Edward Kennedy was a co-sponsor) requiring, among other things, that states test students for proficiency in reading and math and track their progress. Schools that failed to reach their goals would be overhauled or even shut down.

“No longer is it acceptable to hide poor performance,” Bush said. “[W]hen we find poor performance, a school will be given time and incentives and resources to correct their problems.… If, however, schools don’t perform, if, however, given the new resources, focused resources, they are unable to solve the problem of not educating their children, there must be real consequences.”

Did No Child Left Behind make a difference? In 2015, Monty Neil of the anti-standardized testing group FairTest argued that while students made progress after the law was passed, it was slower than in the period before the law . And the No Child Left Behind was the focus of criticism for increasing federal control over schools and an emphasis on standardized testing. Its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, shifted power back to the states.

President Barack Obama had his own signature education law: the grant program Race to the Top, originally part of the 2009 stimulus package, which offered funds to states that undertook various reforms, including expanding charter schools, adopting the Common Core curriculum standards, and reforming teacher evaluation.

One study showed that Race to the Top had a dramatic effect on state practices : even states that didn’t receive the grants adopted reforms. But another said that the actual impact on outcomes were limited —and that there were overly high expectations given the scope of the reforms. “Heightened pressure on districts to produce impossible gains from an overly narrow policy agenda has made implementation difficult and often counterproductive,” wrote Elaine Weiss.

Are we making progress toward a better and more equitable education system? And how will the Trump Administration’s policies alter the trajectory? Yale Insights talked with John King, the secretary of education in the latter years of the Obama administration, who is now president and CEO of the nonprofit Education Trust .

Q: The last two presidents have introduced major education reform efforts. Do you think we’re getting closer to a consensus on the systematic changes that are needed in education?

Well, I’d say we’ve made progress in some important areas over the last couple of decades. We have highest graduation from high school we’ve ever had as a country. Over the last eight years, we had a million African-American and Latino students go on to college. S0 there are signs of progress.

That said, I’m very worried about the current moment. I think there’s a lack of a clear vision from the current administration, the Trump administration, about what direction education should head. And to the extent that they have an articulate vision, I think it’s actually counter to the interests of low-income students and students of color: a dismantling of federal protection of civil rights, a backing-away from the federal commitment to provide aid for students to go to higher education, and undermining of the public commitment to public schools.

That’s a departure. Over the last couple of decades, we’ve had a bipartisan consensus, whether it was in the Bush administration or the Obama administration, that the job of the Department of Education was to advance education equity and to protect student civil rights. The current administration is walking away from both of those things.

I don’t see that as a partisan issue. That’s about this administration and their priorities. Among the first things they did was to reduce civil rights protections for transgender students, to withdraw civil rights protections for victims of sexual assault on higher education campuses. They proposed a budget that cuts funding for students to go to higher education, eliminates all federal support for teacher professional development, and eliminates federal funding for after-school and summer programs.

Q: Some aspects of education reform have focused on improving performance in traditional public schools and others prioritize options like charter schools and private school vouchers. Do you think both of those are needed?

I distinguish between different types of school choice. The vast majority of kids are in traditional, district public schools. We’ve got to make sure that we’re doing everything we can to strengthen those schools and ensure their success.

Then I think there is an important role that high-quality public charters can play if there’s rigorous oversight. And if you think about, say, Massachusetts or New York, there’s a high bar to get a charter, there’s rigorous supervision of the academics and operations of the schools and a willingness to close schools that are low-performing. So for me, those high-quality public charters can contribute as a laboratory for innovation and work in partnership with the broader traditional system.

There’s something very different going on in a place like Michigan, where you’ve got a proliferation of low-quality, for-profit charters run by for-profit companies. Their poorly regulated schools are allowed to continue operating that are doing a terrible job, that are taking advantage of students and families. That’s not what we need. And my view is that states that have those kinds of weak charter laws need to change them and move toward something like Massachusetts where there’s a high bar and meaningful accountability for charters.

And then there’s a whole other category of vouchers, which is using public money for students to go to private school, and to my mind, that is a mistake. We ought to have public dollars going to public schools with public accountability.

Q: When you have a state like Michigan in which you’ve got a lot of very poor charter schools, does that hurt a particular type of student more than others?

It has a disproportionate negative effect on low-income students and students of color. Many of those schools are concentrated in high-needs communities and, unfortunately, it’s really presenting a false choice to parents, a mirage, if you will, because they’re told, “Oh, come to this school, it will be different” or, “it will be better,” and actually it’s not. Ed Trust has an office in Michigan, where we have spent a long time trying to make the case to elected officials that they need to strengthen their charter law and charter accountability.

Unfortunately, there’s a very high level of spending by the for-profit charter industry and their supporters on political campaigns. And so far there’s not been a lot of traction to try to strengthen the charter oversight in Michigan. We see that problem in other states around the country, but at the same time we know there are models that work. We know that in Massachusetts, where there’s a high standard for charters, their Boston charters are some of the highest performing charters in the country, getting great outcomes for high-need students. So it’s possible to do chartering well, but it requires thoughtful leadership from governors and legislators.

Q: What’s your view on how students should be evaluated?

Well, I think we have to have a holistic view. The goal ought to be to prepare students for success in college, in careers, and as citizens. So we want students to have the core academic skills, like English and math, but they also need the knowledge that you gain from science and social studies. They need the experiences that they have in art and music and physical education and health. They need that well-rounded education to be prepared to succeed at what’s next after high school. They also need to be prepared to be critical readers, critical thinkers, to debate ideas with their fellow citizens, to advocate for their ideas in a thoughtful, constructive way—all the tools that you need to be a good citizen.

In order to evaluate all of that, you need multiple measures; you can’t just look at test scores. Obviously you want students to gain reading and math skills, but you also need to look at what courses they’re taking. Are they taking a wide range of courses that will prepare them for success? Do they have access to things like AP courses or International Baccalaureate courses that will prepare them for college-level work? Do they acquire socio-emotional skills? Are they able to navigate when they have a conflict with a peer? Are they able to work collaboratively with peers to solve problems?

So you want to look at grades; you want to look at teachers’ perceptions of students. You want to look at the work that they’re doing in class: is it rigorous, is it really preparing them for life after high school? And one of the challenges in education is, to have those kinds of multiple measures, you need very thoughtful leadership at every level—at state level, district level, and at the school level.

Q: How should we be evaluating teachers?

I started out as a high school social studies teacher, and I thought a lot about this question of what’s the right evaluation method. I think the key is this: you want, as a teacher, to get feedback on how you’re doing and what’s happening in your classroom. Too often teaching can feel very isolated, where it’s just you and the students. It’s important to have systems in place where a mentor teacher, a master teacher, a principal, a department chair is in the classroom observing and giving feedback to teachers and having a continuous conversation about how to improve teaching. That should be a part of an evaluation system.

But so too should be how students are doing, whether or not students are making progress. I know folks worry that that could be reduced to just looking at test scores. I think that would be a mistake, but we ought to ask, if you’re a seventh-grade math teacher, if students are making progress in seventh-grade math.

Now, as we look at that, we have to take into consideration the skills the students brought with them to the classroom, the challenges they face outside of the classroom. But I think what you see in schools that are succeeding is that they have a thoughtful, multiple-measures approach to giving teachers feedback on how they’re doing and see it as a tool for continuous improvement to ensure that everybody is constantly learning.

Q: Do you think the core issue in improving schools is funding? Or are there separate systemic issues that need to be solved?

It varies a lot state to state, but the Education Trust has done extensive analysis of school spending, and what we see is that on average, districts serving low-income students are spending significantly less than more affluent districts across the country, about $1,200 less per student. And in some states, that can be $3,000 less, $5,000 less, $10,000 less per student for the highest-needs kids. We also see a gap around funding for communities that serve large numbers of students of color. Actually, the average gap nationally is larger for districts serving large numbers of students of color—it’s about $2,000 less than those districts that serve fewer students of color.

So we do have a gap in terms of resources coming in, but it’s not just about money; it’s also how you use the money. And we know that, sadly, in many places, the dollars aren’t getting to the highest needs, even within a district. And then once they get to the school level, the question is, are they being spent on teachers and teacher professional development, and things that are going to serve students directly, or are they being spent on central office needs that actually aren’t serving students? So we’ve got to make sure they have more resources for the highest-needs kids, but we’ve also got to make sure that the resources are well-used.

Q: Does it make it significantly harder that so much of the decisions are made on the local level or the state level when you’re trying to create a change across the country?

It’s certainly a challenge. You want to try to balance local leadership with common goals. And you want, as a country, to be able to say, look, you may choose different books to read in class, you may choose different experiments to do in science, but we need all students to have the fundamental skills that they’ll need for success in college and careers and we ought to all be able to agree that all schools should be focused on those skills. Even that can be politically challenging.

We also know that from a funding standpoint, having funding decided mostly on the local level can actually create greater inequality, particularly when you’re relying on local property taxes. You’ll have a very wealthy community that’s spending dramatically more than a neighboring community that has many more low-income families. One of the ways to get around that is to have the state or the federal government account for a larger share of funding so that you can have an equalizing role. That was the original goal of Title I funding at the federal level—to try to get resources to the highest-needs kids.

The other challenge we see is around race and income diversity or isolation. And sadly, in many states, Connecticut included, you have very sharp divisions along race and class lines between districts and so kids may go to school and never see someone different from them. That is a significant problem. We know there are places that are trying to solve that. Hartford, Connecticut, for example, has, because of a court decision, a very extensive effort to get kids from Hartford to go out to suburban schools and suburban kids to come to Hartford schools. And they’ve designed programs that will attract folks across community lines, programs that focus on Montessori or art or early college programs. We can do better, but we need leadership around that.

Q: Are you seeing concrete results from programs like Hartford?

What we know is that low-income students who have the opportunity to go to schools that serve a mixed-income population do better academically. And we also know that all students in schools that are socioeconomically and racially diverse gain additional skills outside the purely academic skills around how to work with peers, cross-racial understanding, empathy.

So, yes, we are seeing those results. The sad thing is, it’s not fast enough; it’s not happening at enough places. We in the Obama administration had proposed a $120 million grant program to school diversity initiatives around the country. We couldn’t get Congress to fund it. We had a small planning grant program that we created at the Education Department that was one of the first things the Trump administration undid when they came into office. So we’re going backwards at the federal level, but there’s a lot of energy around school diversity initiatives at the community level. And that’s where we’re seeing progress around the country.

Q: Do you think the education system should aim to send as many people to college as possible? Should we think of it as being necessary for everyone or should we find ways to prepare students for a wider range of careers?

What’s clear is that everybody going into the 21st-century economy needs some level of post-secondary training. That may be a four-year degree. It could also be a two-year community college degree, or it could be some meaningful career credential that actually leads to a job that provides a family-sustaining wage. But there are very, very few jobs that are going to provide that family-sustaining wage that don’t require some level of post-secondary training. My view is, we have a public responsibility to make sure folks have access to those post-secondary training opportunities. That’s why the Pell Grant program is so important, because it provides funding for low-income students to be able to pursue higher education.

We also need to do a better job in the connection between high school and post-secondary opportunities. A lot of times students leave high school unclear on what they’re going to do and where they should go. We can do a much better job having students have college experiences while in high school and then prepare them to transition into meaningful post-secondary career training.

Q: What’s the one policy change you would made to help students of color and students in poverty, if you had to choose one thing?

There’s no one single silver bullet for sure, but one of the highest return investments we know we can make as a country is in early learning. We know, for example, that high quality pre-K can have an eight-to-one, nine-to-one return on investment. President Obama proposed something called Preschool for All, which would have gotten us toward universal access to quality pre-K for low- and middle-income four-year olds. That’s something we ought to do because if we can give kids a good foundation, that puts them in a better place to succeed in K-12 and to go on to college.

But I have a long list of policy changes I would want to make. I think, fundamentally, we haven’t made that commitment as a country, at the federal level, state level, or local level, to ensuring equitable opportunity for low-income students and students of color. And if we made that commitment, then there’s a series of policy changes that would flow from that.

Interviewed and edited by Ben Mattison.

Visit edtrust.org to learn more about the Education Trust. Follow John B. King Jr. on Twitter: @JohnBKing .

- Public Policy

Seven Solutions for Education Inequality

Giving compass' take:.

- Jermeelah Martin shares seven solutions that can reduce and help to eliminate education inequality in the United States.

- What role are you ready to take on to address education inequality? What does education inequality look like in your community?

- Read about comprehensive strategies for promoting educational equity .

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us .

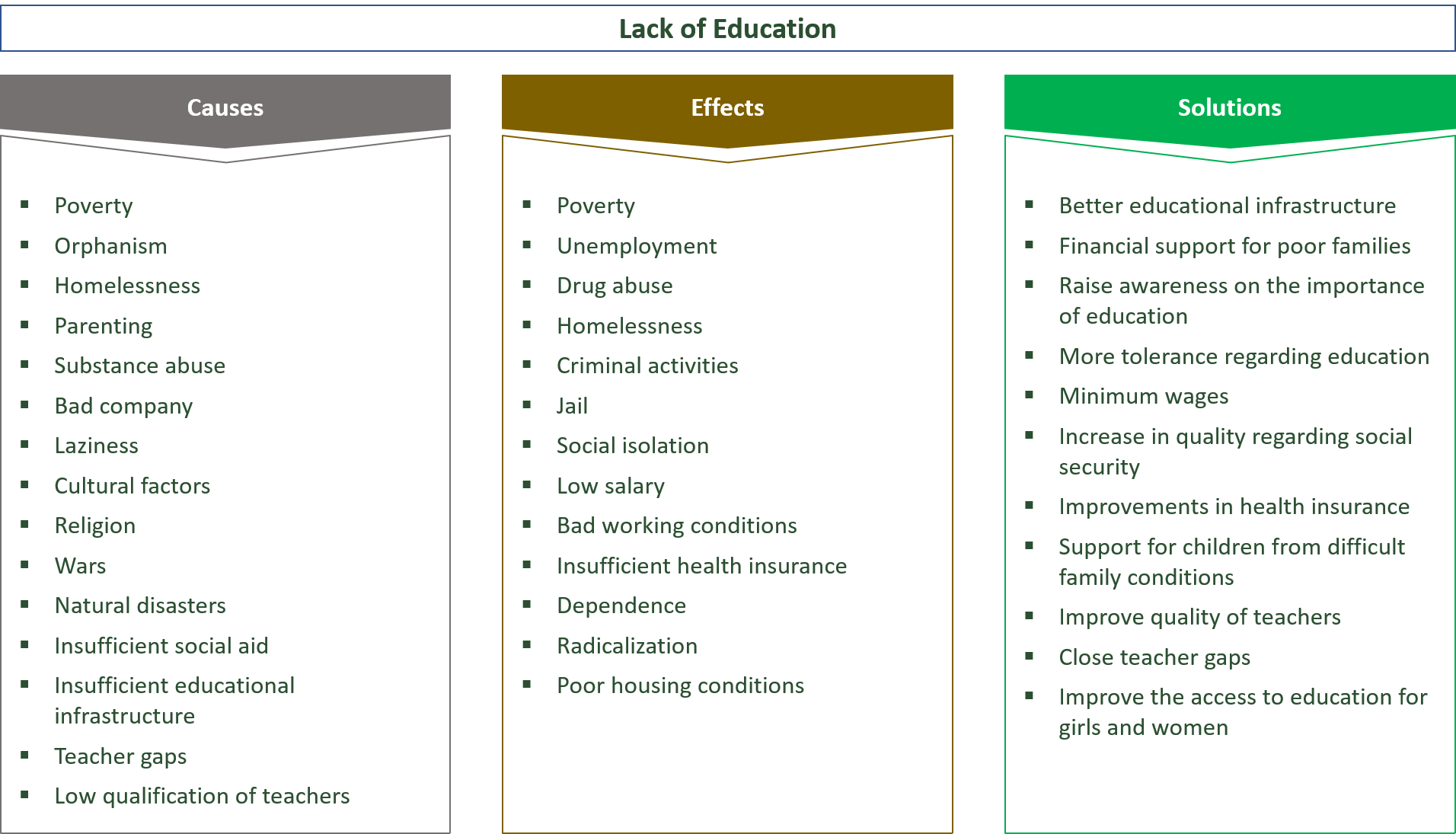

Systemic issues in funding drives education inequality and has detrimental effects primarily on low-income Black and Brown students. These students receive lower quality of education which is reflected through less qualified teachers,not enough books, technologies and special support like counselors and disability services. The lack of access to fair, quality education creates the broader income and wealth gaps in the U.S. Black and brown students face more hurdles to going to college and will be three times more likely to experience poverty as a American with only a highschool degree than an American with a college degree. Income inequality worsens the opportunity for building wealth for Black and Brown families because home and asset ownership will be more difficult to attain.

- Concretely, the first solution would be to reduce class distinctions among students by doing away with the property tax as a primary funding source. This is a significant driver for education inequality because low-income students, by default, will receive less. Instead, the state government should create more significant initiatives and budgets for equitable funding.

- Stop the expansion of charter and private schools as it is not affordable for all students and creates segregation.

- Deprioritize test based funding because it discriminates against disadvantaged students.

- Support teachers financially, as in offering higher salaries and benefits for teachers to improve retention.

- Invest more resources for support in low-income, underfunded schools such as, increased special education specialists and counselors.

- Dismantle the school to prison pipeline for students by adopting more restorative justice efforts and fewer funds for cops in schools. This will create more funds for education justice initiatives and work to end the over policing of minority students.

- More broadly, supporting efforts to dismantle the influence of capitalism in our social sector and supporting an economy that taxes the wealthy at a higher rate will allow for adequate support and funding of public sectors like public education and support for low-income families.

Read the full article about solutions for education inequality by Jermeelah Martin at United for a Fair Economy.

More Articles

Our education funding system is broken. we can fix it., learning policy institute, nov 21, 2022, the funding gap between charter schools and traditional public schools, may 22, 2019.

Become a newsletter subscriber to stay up-to-date on the latest Giving Compass news.

Giving Compass Network

Partnerships & services.

We are a nonprofit too. Donate to Giving Compass to help us guide donors toward practices that advance equity.

Trending Issues

Copyright © 2024, Giving Compass Network

A 501(c)(3) organization. EIN: 85-1311683

The Ongoing Challenges, and Possible Solutions, to Improving Educational Equity

- Share article

Schools across the country were already facing major equity challenges before the pandemic, but the disruptions it caused exacerbated them.

After students came back to school buildings after more than a year of hybrid schooling, districts were dealing with discipline challenges and re-segregating schools. In a national EdWeek Research Center survey from October, 65 percent of the 824 teachers, and school and district leaders surveyed said they were more concerned now than before the pandemic about closing academic opportunity gaps that impact learning for students of different races, socioeconomic levels, disability categories, and English-learner statuses.

But educators trying to prioritize equity have an uphill battle to overcome these challenges, especially in the face of legislation and school policies attempting to fight equity initiatives across the country.

The pandemic and the 2020 murder of George Floyd drove many districts to recognize longstanding racial disparities in academics, discipline, and access to resources and commit to addressing them. But in 2021, a backlash to such equity initiatives accelerated, and has now resulted in 18 states passing laws restricting lessons on race and racism, and many also passing laws restricting the rights and well-being of LGBTQ students.

This slew of Republican-driven legislation presents a new hurdle for districts looking to address racial and other inequities in public schools.

During an Education Week K-12 Essentials forum last week, journalists, educators, and researchers talked about these challenges, and possible solutions to improving equity in education.

Takeru Nagayoshi, who was the Massachusetts teacher of the year in 2020, and one of the speakers at the forum, said he never felt represented as a gay, Asian kid in public school until he read about the Stonewall Riots, the Civil Rights Movement, and the full history of marginalized groups working together to change systems of oppression.

“Those are the learning experiences that inspired me to be a teacher and to commit to a life of making our country better for everyone,” he said.

“Our students really benefit the most when they learn about themselves and the world that they’re in. They’re in a safe space with teachers who provide them with an honest education and accurate history.”

Here are some takeaways from the discussion:

Schools are still heavily segregated

Almost 70 years after the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, most students attend schools where they see a majority of other students of their racial demographics .

Black students, who accounted for 15 percent of public school enrollment in 2019, attended schools where Black students made up an average of 47 percent of enrollment, according to a UCLA report.

They attended schools with a combined Black and Latinx enrollment averaging 67 percent, while Latinx students attended schools with a combined Black and Latinx enrollment averaging 66 percent.

Overall, the proportion of schools where the majority of students are not white increased from 14.8 percent of schools in 2003 to 18.2 percent in 2016.

“Predominantly minority schools [get] fewer resources, and that’s one problem, but there’s another problem too, and it’s a sort of a problem for democracy,” said John Borkowski, education lawyer at Husch Blackwell.

“I think it’s much better for a multi-racial, multi-ethnic democracy, when people have opportunities to interact with one another, to learn together, you know, and you see all of the problems we’ve had in recent years with the rising of white supremacy, and white supremacist groups.”

School discipline issues were exacerbated because of student trauma

In the absence of national data on school discipline, anecdotal evidence and expert interviews suggest that suspensions—both in and out of school—and expulsions, declined when students went remote.

In 2021, the number of incidents increased again when most students were back in school buildings, but were still lower than pre-pandemic levels , according to research by Richard Welsh, an associate professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College of Education.

But forum attendees, who were mostly district and school leaders as well as teachers, disagreed, with 66 percent saying that the pandemic made school incidents warranting discipline worse. That’s likely because of heightened student trauma from the pandemic. Eighty-three percent of forum attendees who responded to a spot survey said they had noticed an increase in behavioral issues since resuming in-person school.

Restorative justice in education is gaining popularity

One reason Welsh thought discipline incidents did not yet surpass pre-pandemic levels despite heightened student trauma is the adoption of restorative justice practices, which focus on conflict resolution, understanding the causes of students’ disruptive behavior, and addressing the reason behind it instead of handing out punishments.

Kansas City Public Schools is one example of a district that has had improvement with restorative justice, with about two thirds of the district’s 35 schools seeing a decrease in suspensions and expulsions in 2021 compared with 2019.

Forum attendees echoed the need for or success of restorative justice, with 36 percent of those who answered a poll within the forum saying restorative justice works in their district or school, and 27 percent saying they wished their district would implement some of its tenets.

However, 12 percent of poll respondents also said that restorative justice had not worked for them. Racial disparities in school discipline also still persist, despite restorative justice being implemented, which indicates that those practices might not be ideal for addressing the over-disciplining of Black, Latinx, and other historically marginalized students.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Education and inequality in 2021: how to change the system

Research Associate at the University of Geneva's department of Education and Psychology; Campus and Secondary Principal at the International School of Geneva's La Grande Boissière, Université de Genève

Disclosure statement

Conrad Hughes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

AUF (Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie) provides funding as a member of The Conversation FR.

View all partners

Since its earliest traces, at least 5,000 years ago , formal education – meaning an education centred on literacy and numeracy – has always been highly selective. Ancient Egyptian priest schools and schools for scribes in Sumeria were only open to the children of the clergy or future monarchs.

Later on, the wealthy would use private tutors, such as the Sophists of Athens (500 - 400 BCE). Ancient Greek schools, such as Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum , were restricted to a small elite group. Formal education was reserved for male children who were wealthy, able, and privileged.

Through time, even after learning societies began to flourish, it was still an education for some and not for everybody.

In the 1800s Black people were denied access to quality education in the United States. In European colonies, education was used to strip people of their cultural heritage and relegate them to a future of menial labour.

Education has always been less accessible to women than men. Even today, over 130 million girls are still out of school. Although the difference between girls and boys is lessening, the disparity disadvantaging girls persists . From a socioeconomic perspective, in many countries, private schools continue to grow alongside compulsory state schools, offering a different style of education, sometimes at a very high price.

Today, progress to attain the dream of universal access to education is slow. UNESCO’s Education for All and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 , which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, are still far from materialising: roughly 260 million children are still not in school . The COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation worse: remote learning is inaccessible to roughly 500 million students . Estimates are that over 200 million children will still be out of school by 2030 .

In my study “Education and Elitism” , the overarching question that runs through the book is about the future of education worldwide: What are the prospects for the future? Are we facing an even more enclaved, pauperised majority while a tiny minority become more powerful and wealthy?

Certain paths could open up. On the one hand, places in selective institutions could become even more difficult to access while private education strips ahead of national standards. On the other hand, changes might make education more inclusive: this would include scholarships, cheaper private education, more robust state systems and deep assessment reform.

Prospects for the future

Scholarship programmes: These allow the brightest and poorest access to transformative learning ecosystems . However, this contributes to a brain drain and does not develop the local educational sector , particularly in Africa.

Cheaper private education: A movement of accessible private schools is growing . This allows more children to access some of the value-added features of such systems – more curriculum flexibility, smaller class sizes, more individual student tracking. However, there are reports that this is widening social divides , as the public system isn’t improving fast enough to keep up.

More robust state systems: UNESCO estimates that it would cost a total of US$340 billion each year to achieve universal pre-primary, primary, and secondary education in low- and lower-middle-income countries by 2030. The average annual per-student spending for quality primary education in a low-income country is predicted to be US$197 in 2030. This creates an estimated annual gap of US$39 billion between 2015 and 2030. Financing this gap calls for action from private sector donors, philanthropists, and international financial institutions.

Online learning: The COVID-19 lockdown has brought inequalities to the surface. However, the rise of online learning worldwide has been phenomenal. This opens up the potential to widen access to learning socioeconomically and, if delivered by skilled facilitators, academically . There is a problem, though: online instruction lacks the emotional quantum that face-to-face learning creates. Because of this, motivation levels and persistence tend to be low in online learning environments . And importantly, in many countries, many students still don’t have access to the internet.

A way forward: reforming the system

Perhaps the most substantive movement to reduce inequalities would not be to accelerate access to a broken system but to reform the system itself .

It is time to look further than narrow academic metrics as the only way of describing young people’s competences. The whole educational system across high schools, in every country, needs to change dramatically. Assessment models should recognise and nurture more varied and multiple competences, in particular, attitudes, skills and types of knowledge beyond those concentrated in constructs that are favoured by socioeconomic background, such as literacy and numeracy .

Read more: Education needs a refocus so that all learners reach their full potential

Until universities and employers look beyond traditional metrics, it will be difficult to break a circuit that favours, for the large part, middle class, socially and ethnically privileged candidates.

To truly break away from a millennia of elitist, selective systems , the approach needs to move from pure academics to a credit system that captures many more stories of learning. This new credit system should be known as a passport, meaning students have stamped it with the various competences such as lifelong learning and self-agency that they have developed throughout their learning (in an out of school), allowing them to be recognised on numerous different fronts.

A coalition of schools from every continent is working on this project, now seeking universities to sit around the table in order to bring this work to its conclusion. This would mean co-designing an elegant, life worthy transcript to allow more access to more children based on more expansive criteria.

- Peacebuilding

- Education inequality

- Women and girls

- Out of school children

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

#LeadingSDG4 | Education2030

- Dashboard of country commitments

- Country profiles

- Global Education Observatory

- SDG4 scorecard

- Evidence and policy

- Education financing

- Global Education Coalition

- Futures of Education

- Greening Education Partnership

- Gateways to Public Digital Learning

- The Coalition for Foundational Learning

- Education in Crisis Situations: Partnership for Transformative Actions

- Global Platform for Gender Equality and Girls’ and Women’s Empowerment in and through Education

- Global Youth Initiative

- Good practices

- Youth Declaration on Transforming Education

- SDG4 Youth & Student Network

- Youth Resources

Education in Crisis Situations

The Global Initiative – Partnership for Transformative Actions in Crisis Situations in the first global multi-stakeholder initiative to mobilize cross-country cooperation and bring actions to scale while addressing immediate educational needs at national, regional, and global levels.

As 244 million children and young people are currently affected by armed conflict, health, or climate-induced disasters, political or economic crises, and associated forced displacement, including refugee crises, the need to intervene and put an end to the vicious cycle is urgent. Crises dramatically impact the longer-term investment required to transform education systems and to ensure their resilience to future disruption.

With the main objective of advocating for and implementing the Humanitarian-Development- Peacebuilding Triple Nexus, the Global Initiative was launched as the main framework for its actions which targets 4 areas:

- Inclusive education: Improve equitable inclusive education access and learning outcomes for children and youth affected by crises.

- Finance: Protect and improve external financing, ensure it reaches learners equitably and aligns with national planning priorities and commitments to international conventions.

- System Strengthening: Build inclusive, crisis-resilient education systems that ensure protection of the right to education for children and youth, address the needs of all learners in a holistic way, and include information and tools related to safeguarding health, wellbeing, nutrition, water, sanitation and protection from violence, sexual exploitation and abuse.

- Interlinked priorities: Scale and mainstream high-impact and evidence-based interventions into policy and programming efforts with a focus on eight inter-linked priorities: (i) teachers; (ii) community participation; (iii) gender equality and inclusion; (iv) early childhood education; (v) mental health and psychosocial support; (vi) protection from violence; (vii) equitable delivery of education technology and innovation, especially for the most marginalized children; and (viii) meaningful child and youth engagement.

Strategies and activities

For the Partnership, implementing this initiative means making it relevant for those most in need, with a focus on tangible actions where it matters most: on the ground, in the classroom, and in the experience of teachers and learners alike. Moving forward is about making this Call to Action meaningful in concerned countries and thinking of its implementation based on the different feedback and contexts.

Thus, out of the 36 members who have signed off, an agreement was made to focus on the following 14 countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Colombia, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iraq, Jordan, Niger, South Sudan, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, Zambia. Based on National consultations held in the 14 countries, the Operationalization plan of the Global Initiative – Partnership for Transformative Actions in Crisis Situations focuses on solutions that:

- Identifies ways to strengthen political accountability for transforming and financing education in crisis situations

- Draws the main guidelines to implement the 4 pillars of the Global Initiative

- Establishes a clear roadmap staged with milestones until December 2024.

- Map the national consultation commitments to concrete country-level actions supported by engaged EiEPC stakeholders on the ground.

- Anchor interventions to national, regional, and global monitoring and reporting mechanisms with a first status report published in September 2025 reflecting adaptations and adjustments that enable meaningful, contextualized action and monitoring.

Co-conveners

The co-conveners of the Call-to-Action: Education in crisis situations are:

- Education Cannot Wait

- Global Partnership for Education

Partners

The Global Initiative has been signed and endorsed by the following 36 Member States: Cameroon, Canada, Chad, Denmark, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Germany, Haiti, Jordan, Lebanon, Lithuania, Madagascar, Niger, Norway, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Qatar, South Sudan, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, European Union, ECW, GPE, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNICEF, INEE, EiE Champion Group (coalition of more than 90 CSOs), The LEGO Foundation

How to engage

The best way to engage for countries and organizations remains to endorse the CtA. Being engaged means to make a living and transformative commitment for the most in need and to fully capitalize on this unique opportunity. It must be done by:

- Nurturing and sustaining the political commitment and resources mobilized to support countries to adhere to the pillars of the Call to Action

- Engaging all stakeholders at local, national, regional, and global levels to create a movement beyond ministries of education, led by learners and teachers across the world, inspired by civil society, and connected with broader movements for positive change.

- Strengthening existing clusters and working groups on Education in Emergencies and reinforce open and effective Triple Nexus partnership platforms.

- Gathering robust data and evidence to transpose the national consultation commitments to concrete country-level actions supported by engaged EiEPC stakeholders on the ground

- Taking proactive and transformative measures to address the key barriers and bottlenecks to education in crisis situations, with a focus on the most marginalized populations.

- Accounting for progress on global, regional, and national commitments on education in crisis situations in and through education.

Related items

- UN & International cooperation

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

Ending Poverty Through Education: The Challenge of Education for All

About the author, koïchiro matsuura.

From Vol. XLIV, No. 4, "The MDGs: Are We on Track?", December 2007

T he world made a determined statement when it adopted the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000. These goals represent a common vision for dramatically reducing poverty by 2015 and provide clear objectives for significant improvement in the quality of people's lives. Learning and education are at the heart of all development and, consequently, of this global agenda. MDG 2 aims to ensure that children everywhere -- boys and girls -- will be able to complete a full course of good quality primary schooling. MDG 3 targets to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015. Indeed, learning is implicit in all the MDGs: improving maternal health, reducing child mortality and combating HIV/AIDS simply cannot be achieved without empowering individuals with knowledge and skills to better their lives. In addition, MDG 8 calls for "more generous official development assistance for countries committed to poverty reduction". The MDGs on education echo the Education for All (EFA) goals, also adopted in 2000. However, the EFA agenda is much broader, encompassing not only universal primary education and gender equality, but also early childhood education, quality lifelong learning and literacy. This holistic approach is vital to ensuring full enjoyment of the human right to education and achieving sustainable and equitable development. What progress have we made towards universal primary education? The EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008 -- Education for All by 2015: Will we make it? -- presents an overall assessment of progress at the halfway point between 2000 and 2015. There is much encouraging news, including: • Between 1999 and 2005, the number of children entering primary school for the first time grew by 4 per cent, from 130 million to 135 million, with a jump of 36 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa -- a major achievement, given the strong demographic growth in the region. • Overall participation in primary schooling worldwide grew by 6.4 per cent, with the fastest growth in the two regions farthest from achieving the goal on education -- sub-Saharan Africa, and South and West Asia. • Looking at the net enrolment ratio, which measures the share of children of primary school age who are enrolled, more than half the countries of North America, Western, Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia and the Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean have rates of over 90 per cent. Ratios are lower in the Arab States, Central Asia and South and West Asia, with lows of 33 per cent (Djibouti) and 68 per cent (Pakistan). The challenge is greatest in sub-Saharan Africa, where more than one third of countries have rates below 70 per cent. • The number of children out of school has dropped sharply, from 96 million in 1999 to around 72 million by 2005, with the biggest change in sub-Saharan Africa and South and West Asia, which continue to harbour the largest percentages of children not in school. South and West Asia has the highest share of girls out of school. The MDG on education specifies that both boys and girls should receive a full course of primary schooling. The gender parity goal set for 2005, however, has not been achieved by all. Still, many countries have made significant progress. In South and West Asia, one of the regions with the widest disparities, 93 girls for every 100 boys were in school in 2005 -- up from 82 in 1999. Yet, globally, 122 out of the 181 countries with data had not achieved gender parity in 2005. There is much more to be done, particularly in rural areas and urban slums, but there are strong trends in the right direction. This overall assessment indicates that progress in achieving universal primary education is positive. Countries where enrolments rose sharply generally increased their education spending as a share of gross national product. Public expenditure on education has climbed by over 5 per cent annually in sub-Saharan Africa and South and West Asia. Aid to basic education in low-income countries more than doubled between 2000 and 2004. Progress has been achieved through universal and targeted strategies. Some 14 countries have abolished primary school fees since 2000, a measure that has promoted enrolment of the most disadvantaged children. Several countries have established mechanisms to redistribute funds to poorer regions and target areas that are lagging in terms of access to education, and to offset economic barriers to schooling for poor households. Many countries, including Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, India and Yemen, have introduced specific strategies to encourage girls' schooling, such as community sensitization campaigns, early childhood centres to release girls from caring for their siblings, free uniforms and learning materials. These strategies are working and reflect strong national commitment to achieving universal primary education. Enrolment, however, is only half the story; children need to stay in primary school and complete it. One way of measuring this is the survival rate to the last grade of primary education. Although data are not available for every country, globally the rate of survival to the last grade is 87 per cent. This masks wide regional variations, with medians of over 90 per cent all over the world, except in South and West Asia (79%) and sub-Saharan Africa (63%). Even then, some children drop out in the last grade and never complete primary education, with some countries showing a gap of 20 per cent between those who enter the last grade and those who complete it. One of the principal challenges is to improve the quality of learning and teaching. Cognitive skills, basic competencies and life-skills, as well as positive values and attitudes, are all essential for development at individual, community and national levels. In a world where the acquisition, use and sharing of knowledge are increasingly the key to poverty reduction and social development, the need for quality learning outcomes becomes a necessary essential condition for sharing in the benefits of growing prosperity. What children take away from school, and what youth and adults acquire in non-formal learning programmes, should enable them, as expressed in the four pillars of the 1996 Delors report, Learning: The Treasure Within, to learn to know, to do, to be and to live together. Governments are showing growing concern about the poor quality of education. An increasing number of developing countries are participating in international and regional learning assessments, and conducting their own. Evidence shows that up to 40 per cent of students do not reach minimum achievement standards in language and mathematics. Pupils from more privileged socio-economic backgrounds and those with access to books consistently perform better than those from poorer backgrounds with limited access to reading materials. Clear messages emerge from these studies. In primary education, quality learning depends, first and foremost, on the presence of enough properly trained teachers. But pupil/teacher ratios have increased in sub-Saharan Africa and South and West Asia since 1999. Some 18 million new teachers are needed worldwide to reach universal primary education by 2015. Other factors have a clear influence on learning: a safe and healthy physical environment, including, among others, appropriate sanitation for girls; adequate learning and teaching materials; child-centred curricula; and sufficient hours of instruction (at least 800 hours a year). Initial learning through the mother tongue has a proven impact on literacy acquisition. Transparent and accountable school governance, among others, also affects the overall learning environment. What then are the prospects for achieving universal primary education and gender parity? The EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008 puts countries into two categories depending on their current net enrolment rate: 80 to 96 per cent, and less than 80 per cent. For each category, it then assesses whether current rates of progress are likely to enable each country to reach the goal by 2015. Noting that 63 countries worldwide have already achieved the goal and 54 countries cannot be included in the analysis due to lack of adequate data, the status is as follows: Out of the 95 countries unlikely to achieve gender parity by 2015, 14 will not achieve it in primary education and 52 will not attain it at the secondary level. A further 29 countries will fail to achieve parity in both primary and secondary education. The international community must focus on giving support to those countries that are currently not on track to meet the MDGs and the EFA goals, and to those that are making progress. On current trends, and if pledges are met, bilateral aid to basic education will likely reach $5 billion a year in 2010. This remains well below the $9 billion required to reach universal primary education alone; an additional $2 billion are needed to address the wider context of educational development. Ensuring that adults, particularly mothers, are literate has an impact on whether their children, especially their daughters, attend school. In today's knowledge-intensive societies, 774 million adults are illiterate -- one in four of them women. Early learning and pre-school programmes give children a much better chance to survive and succeed once they enter primary school, but such opportunities are few and far between across most of the developing world, except in Latin America and the Caribbean. Opportunities for quality secondary education and ongoing learning programmes provide motivation for students to achieve the highest possible level of education and view learning as a lifelong endeavour. The goals towards which we are striving are about the fundamental right to education that should enable every child and every adult to develop their potential to the full, so that they contribute actively to societal change and enjoy the benefits of development. The challenge now is to ensure that learning opportunities reach all children, youth and adults, regardless of their background. This requires inclusive policies to reach the most marginalized, vulnerable and disadvantaged populations -- the working children, those with disabilities, indigenous groups, linguistic minorities and populations affected by HIV/AIDS.

Globally, the world has set its sights on sustainable human development, the only prospect for reducing inequalities and improving the quality of life for present and future generations. In this perspective, Governments, donors and international agencies must continue working jointly towards achieving universal primary education and the broader MDG agenda with courage, determination and unswerving commitment. To find out more about the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008, please visit ( www.efareport.unesco.org ).

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

World Down Syndrome Day: A Chance to End the Stereotypes

The international community, led by the United Nations, can continue to improve the lives of people with Down syndrome by addressing stereotypes and misconceptions.

Central Emergency Response Fund’s Climate Action Account: Supporting People and Communities Facing the Climate Crisis

While the climate crisis looms large, there is reason for hope: the launch of the climate action account of the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) fills a critical gap in the mosaic of climate financing arrangements.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Taiwan sees warning signs in weakening congressional support for Ukraine

How dating sites automate racism

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

The costs of inequality: education’s the one key that rules them all.

When there’s inequity in learning, it’s usually baked into life, Harvard analysts say

Corydon Ireland

Harvard Correspondent

Third in a series on what Harvard scholars are doing to identify and understand inequality, in seeking solutions to one of America’s most vexing problems.

Before Deval Patrick ’78, J.D. ’82, was the popular and successful two-term governor of Massachusetts, before he was managing director of high-flying Bain Capital, and long before he was Harvard’s most recent Commencement speaker , he was a poor black schoolchild in the battered housing projects of Chicago’s South Side.

The odds of his escaping a poverty-ridden lifestyle, despite innate intelligence and drive, were long. So how did he help mold his own narrative and triumph over baked-in societal inequality ? Through education.

“Education has been the path to better opportunity for generations of American strivers, no less for me,” Patrick said in an email when asked how getting a solid education, in his case at Milton Academy and at Harvard, changed his life.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.”

If inequality starts anywhere, many scholars agree, it’s with faulty education. Conversely, a strong education can act as the bejeweled key that opens gates through every other aspect of inequality , whether political, economic , racial, judicial, gender- or health-based.

Simply put, a top-flight education usually changes lives for the better. And yet, in the world’s most prosperous major nation, it remains an elusive goal for millions of children and teenagers.

Plateau on educational gains

The revolutionary concept of free, nonsectarian public schools spread across America in the 19th century. By 1970, America had the world’s leading educational system, and until 1990 the gap between minority and white students, while clear, was narrowing.

But educational gains in this country have plateaued since then, and the gap between white and minority students has proven stubbornly difficult to close, says Ronald Ferguson, adjunct lecturer in public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and faculty director of Harvard’s Achievement Gap Initiative. That gap extends along class lines as well.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.” — Deval Patrick

In recent years, scholars such as Ferguson, who is an economist, have puzzled over the ongoing achievement gap and what to do about it, even as other nations’ school systems at first matched and then surpassed their U.S. peers. Among the 34 market-based, democracy-leaning countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States ranks around 20th annually, earning average or below-average grades in reading, science, and mathematics.

By eighth grade, Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer Jr. noted last year, only 44 percent of American students are proficient in reading and math. The proficiency of African-American students, many of them in underperforming schools, is even lower.

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming,” wrote Fryer, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, who used the OECD rankings as a metaphor for minority standing educationally. “If they were to be considered a country, they would rank just below Mexico in last place.”

Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Dean James E. Ryan, a former public interest lawyer, says geography has immense power in determining educational opportunity in America. As a scholar, he has studied how policies and the law affect learning, and how conditions are often vastly unequal.