Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

The Egyptian pyramid chain was built along the now abandoned Ahramat Nile Branch

- Eman Ghoneim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3988-0335 1 ,

- Timothy J. Ralph ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4956-606X 2 ,

- Suzanne Onstine 3 ,

- Raghda El-Behaedi 4 ,

- Gad El-Qady 5 ,

- Amr S. Fahil 6 ,

- Mahfooz Hafez 5 ,

- Magdy Atya 5 ,

- Mohamed Ebrahim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4068-5628 5 ,

- Ashraf Khozym 5 &

- Mohamed S. Fathy 6

Communications Earth & Environment volume 5 , Article number: 233 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Archaeology

- Geomorphology

- Hydrogeology

- Sedimentology

The largest pyramid field in Egypt is clustered along a narrow desert strip, yet no convincing explanation as to why these pyramids are concentrated in this specific locality has been given so far. Here we use radar satellite imagery, in conjunction with geophysical data and deep soil coring, to investigate the subsurface structure and sedimentology in the Nile Valley next to these pyramids. We identify segments of a major extinct Nile branch, which we name The Ahramat Branch, running at the foothills of the Western Desert Plateau, where the majority of the pyramids lie. Many of the pyramids, dating to the Old and Middle Kingdoms, have causeways that lead to the branch and terminate with Valley Temples which may have acted as river harbors along it in the past. We suggest that The Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and that it was simultaneously active and used as a transportation waterway for workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites.

Introduction

The landscape of the northern Nile Valley in Egypt, between Lisht in the south and the Giza Plateau in the north, was subject to a number of environmental and hydrological changes during the past few millennia 1 , 2 . In the Early Holocene (~12,000 years before present), the Sahara of North Africa transformed from a hyper-arid desert to a savannah-like environment, with large river systems and lake basins 3 , 4 due to an increase in global sea level at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). The wet conditions of the Sahara provided a suitable habitat for people and wildlife, unlike in the Nile Valley, which was virtually inhospitable to humans because of the constantly higher river levels and swampy environment 5 . At this time, Nile River discharge was high, which is evident from the extensive deposition of organic-rich fluvial sediment in the Eastern Mediterranean basin 6 . Based on the interpretation of archeological material and pollen records, this period, known as the African Humid Period (AHP) (ca. 14,500–5000 years ago), was the most significant and persistent wet period from the early to mid-Holocene in the eastern Sahara region 7 , with an annual rainfall rate of 300–920 mm yr −1 8 . During this time the Nile would have had several secondary channels branching across the floodplain, similar to those described by early historians (e.g., Herodotus).

During the mid-Holocene (~10,000–6000 years ago), freshwater marshes were common within the Nile floodplain causing habitation to be more nucleated along the desert margins of the Nile Valley 9 . The desert margins provided a haven from the high Nile water. With the ending of the AHP and the beginning of the Late Holocene (~5500 years ago to present), rainfall greatly declined, and the region’s humid phase gradually came to an end with punctuated short wet episodes 10 . Due to increased aridity in the Sahara, more people moved out of the desert towards the Nile Valley and settled along the edge of the Nile floodplain. With the reduced precipitation, sedimentation increased in and around the Nile River channels causing the proximal floodplain to rise in height and adjacent marshland to decrease in the area 11 , 12 estimated the Nile flood levels to have ranged from 1 to 4 m above the baseline (~5000 BP). Inhabitants moved downhill to the Nile Valley and settled in the elevated areas on the floodplain, including the raised natural levees of the river and jeziras (islands). This was the beginning of the Old Kingdom Period (ca. 2686 BCE) and the time when early pyramid complexes, including the Step Pyramid of Djoser, were constructed at the margins of the floodplain. During this time the Nile discharge was still considerably higher than its present level. The high flow of the river, particularly during the short-wet intervals, enabled the Nile to maintain multiple branches, which meandered through its floodplain. Although the landscape of the Nile floodplain has greatly transformed due to river regulation associated with the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, this region still retains some clear hydro-geomorphological traces of the abandoned river channels.

Since the beginning of the Pharaonic era, the Nile River has played a fundamental role in the rapid growth and expansion of the Egyptian civilization. Serving as their lifeline in a largely arid landscape, the Nile provided sustenance and functioned as the main water corridor that allowed for the transportation of goods and building materials. For this reason, most of the key cities and monuments were in close proximity to the banks of the Nile and its peripheral branches. Over time, however, the main course of the Nile River laterally migrated, and its peripheral branches silted up, leaving behind many ancient Egyptian sites distant from the present-day river course 9 , 13 , 14 , 15 . Yet, it is still unclear as to where exactly the ancient Nile courses were situated 16 , and whether different reaches of the Nile had single or multiple branches that were simultaneously active in the past. Given the lack of consensus amongst scholars regarding this subject, it is imperative to develop a comprehensive understanding of the Nile during the time of the ancient Egyptian civilization. Such a poor understanding of Nile River morphodynamics, particularly in the region that hosts the largest pyramid fields of Egypt, from Lisht to Giza, limits our understanding of how changes in the landscape influenced human activities and settlement patterns in this region, and significantly restricts our ability to understand the daily lives and stories of the ancient Egyptians.

Currently, much of the original surface of the ancient Nile floodplain is masked by either anthropogenic activity or broad silt and sand sheets. For this reason, singular approaches such as on-ground searches for the remains of hidden former Nile branches are both increasingly difficult and inauspicious. A number of studies have already been carried out in Egypt to locate segments of the ancient Nile course. For instance 9 , proposed that the axis of the Nile River ran far west of its modern course past ancient cities such as el-Ashmunein (Hermopolis) 13 . mapped the ancient hydrological landscape in the Luxor area and estimated both an eastward and westward Nile migration rate of 2–3 km per 1000 years. In the Nile Delta region 17 , detected several segments of buried Nile distributaries and elevated mounds using geoelectrical resistivity surveys. Similarly, a study by Bunbury and Lutley 14 identified a segment of an ancient Nile channel, about 5000 years old, near the ancient town of Memphis ( men-nefer ). More recently 15 , used cores taken around Memphis to reveal a section of a lateral ancient Nile branch that was dated to the Neolithic and Predynastic times (ca. 7000–5000 BCE). On the bank of this branch, Memphis, the first capital of unified Egypt, was founded in early Pharaonic times. Over the Dynastic period, this lateral branch then significantly migrated eastwards 15 . A study by Toonen et al. 18 , using borehole data and electrical resistivity tomography, further revealed a segment of an ancient Nile branch, dating to the New Kingdom Period, situated near the desert edge west of Luxor. This river branch would have connected important localities and thus played a significant role in the cultural landscape of this area. More recent research conducted further north by Sheisha et al. 2 , near the Giza Plateau, indicated the presence of a former river and marsh-like environment in the floodplain east of the three great Pyramids of Giza.

Even though the largest concentration of pyramids in Egypt are located along a narrow desert strip from south Lisht to Giza, no explanation has been offered as to why these pyramid fields were condensed in this particular area. Monumental structures, such as pyramids and temples, would logically be built near major waterways to facilitate the transportation of their construction materials and workers. Yet, no waterway has been found near the largest pyramid field in Egypt, with the Nile River lying several kilometers away. Even though many efforts to reconstruct the ancient Nile waterways have been conducted, they have largely been confined to small sites, which has led to the mapping of only fragmented sections of the ancient Nile channel systems.

In this work, we present remote sensing, geomorphological, soil coring and geophysical evidence to support the existence of a long-lost ancient river branch, the Ahramat Branch, and provide the first map of the paleohydrological setting in the Lisht-Giza area. The finding of the Ahramat Branch is not only crucial to our understanding of why the pyramids were built in these specific geographical areas, but also for understanding how the pyramids were accessed and constructed by the ancient population. It has been speculated by many scholars that the ancient Egyptians used the Nile River for help transporting construction materials to pyramid building sites, but until now, this ancient Nile branch was not fully uncovered or mapped. This work can help us better understand the former hydrological setting of this region, which would in turn help us learn more about the environmental parameters that may have influenced the decision to build these pyramids in their current locations during the time of Pharaonic Egypt.

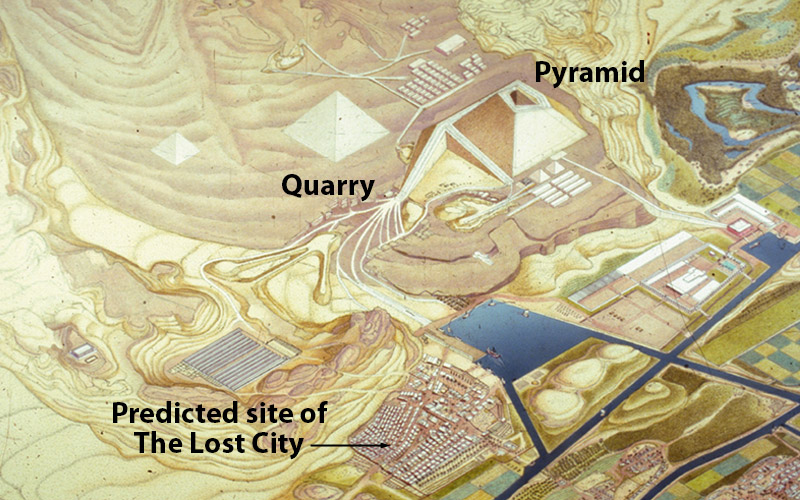

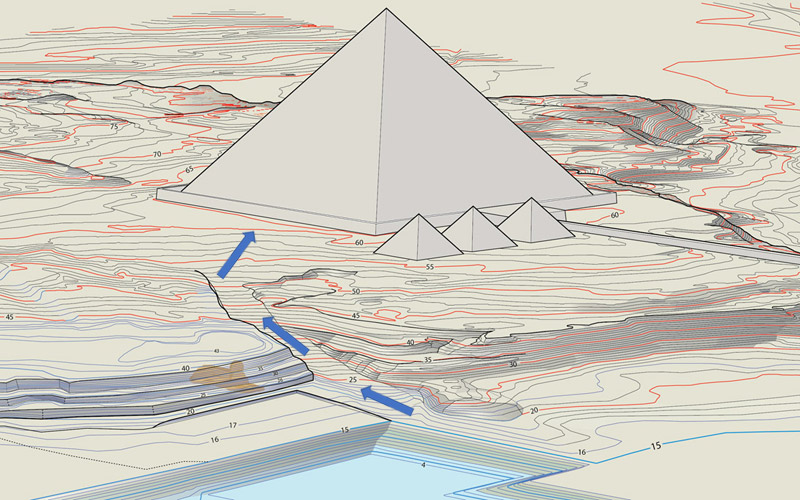

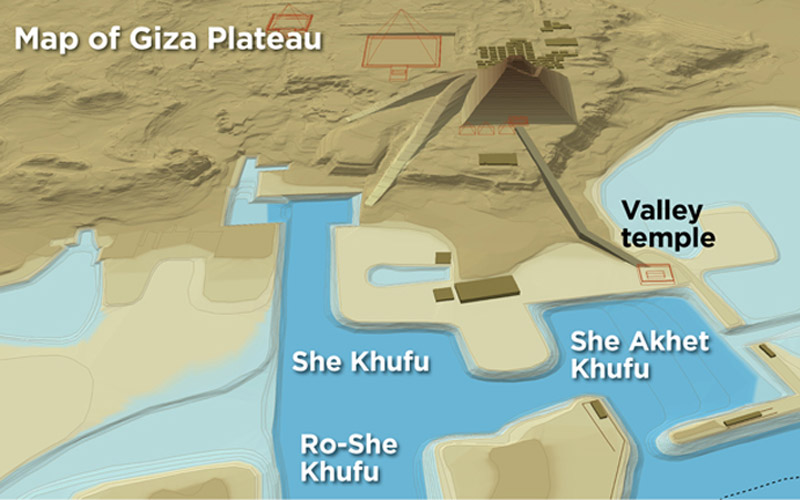

Position and morphology of the Ahramat Branch

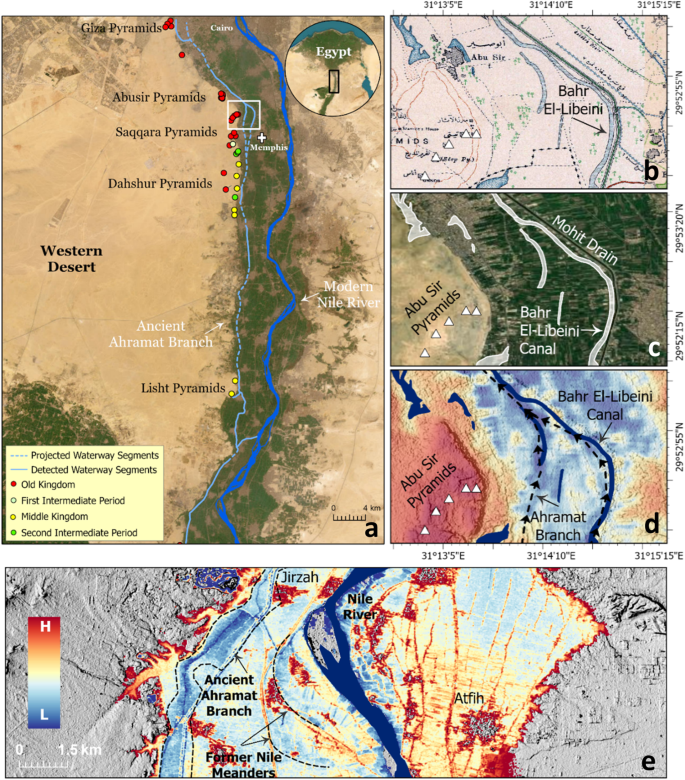

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery and radar high-resolution elevation data for the Nile floodplain and its desert margins, between south Lisht and the Giza Plateau area, provide evidence for the existence of segments of a major ancient river branch bordering 31 pyramids dating from the Old Kingdom to Second Intermediate Period (2686−1649 BCE) and spanning between Dynasties 3–13 (Fig. 1a ). This extinct branch is referred to hereafter as the Ahramat Branch, meaning the “Pyramids Branch” in Arabic. Although masked by the cultivated fields of the Nile floodplain, subtle topographic expressions of this former branch, now invisible in optical satellite data, can be traced on the ground surface by TanDEM-X (TDX) radar data and the Topographic Position Index (TPI). Data analysis indicates that this lateral distributary channel lies between 2.5 and 10.25 km west from the modern Nile River. The branch appears to have a surface channel depth between 2 and 8 m, a channel length of about 64 km and a channel width of 200–700 m, which is similar to the width of the contemporary neighboring Nile course. The size and longitudinal continuity of the Ahramat Branch and its proximity to all the pyramids in the study area implies a functional waterway of great significance.

a Shows the Ahramat Branch borders a large number of pyramids dating from the Old Kingdom to the 2 nd Intermediate Period and spanning between Dynasties 3 and 13. b Shows Bahr el-Libeini canal and remnant of abandoned channel visible in the 1911 historical map (Egyptian Survey Department scale 1:50,000). c Bahr el-Libeini canal and the abandoned channel are overlain on satellite basemap. Bahr el-Libeini is possibly the last remnant of the Ahramat Branch before it migrated eastward. d A visible segment of the Ahramat Branch in TDX is now partially occupied by the modern Bahr el-Libeini canal. e A major segment of the Ahramat Branch, approximately 20 km long and 0.5 km wide, can be traced in the floodplain along the Western Desert Plateau south of the town of Jirza. Location of e is marked in white a box in a . (ESRI World Image Basemap, source: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics).

A trace of a 3 km river segment of the Ahramat Branch, with a width of about 260 m, is observable in the floodplain west of the Abu Sir pyramids field (Fig. 1b–d ). Another major segment of the Ahramat Branch, approximately 20 km long and 0.5 km wide can be traced in the floodplain along the Western Desert Plateau south of the town of Jirza (Fig. 1e ). The visible segments of the Ahramat Branch in TDX are now partially occupied by the modern Bahr el-Libeini canal. Such partial overlap between the courses of this canal, traced in the1911 historical maps (Egyptian Survey Department scale 1:50,000), and the Ahramat Branch is clear in areas where the Nile floodplain is narrower (Fig. 1b–d ), while in areas where the floodplain gets wider, the two water courses are about 2 km apart. In light of that, Bahr el-Libeini canal is possibly the last remnant of the Ahramat Branch before it migrated eastward, silted up, and vanished. In the course of the eastward migration over the Nile floodplain, the meandering Ahramat Branch would have left behind traces of abandoned channels (narrow oxbow lakes) which formed as a result of the river erosion through the neck of its meanders. A number of these abandoned channels can be traced in the 1911 historical maps near the foothill of the Western Desert plateau proving the eastward shifting of the branch at this locality (Fig. 1b–d ). The Dahshur Lake, southwest of the city of Dahshur, is most likely the last existing trace of the course of the Ahramat Branch.

Subsurface structure and sedimentology of the Ahramat Branch

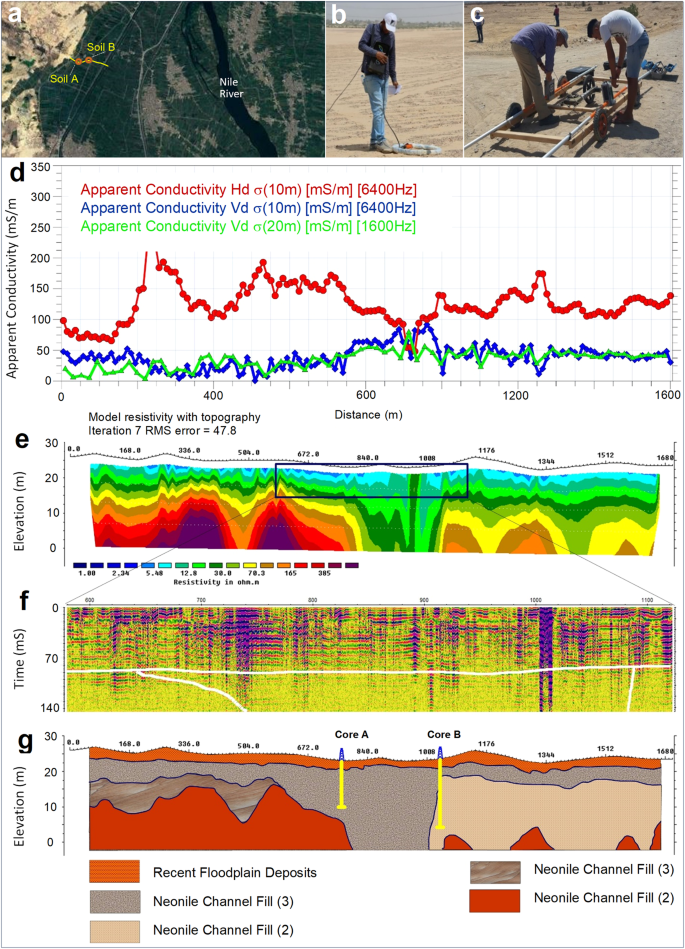

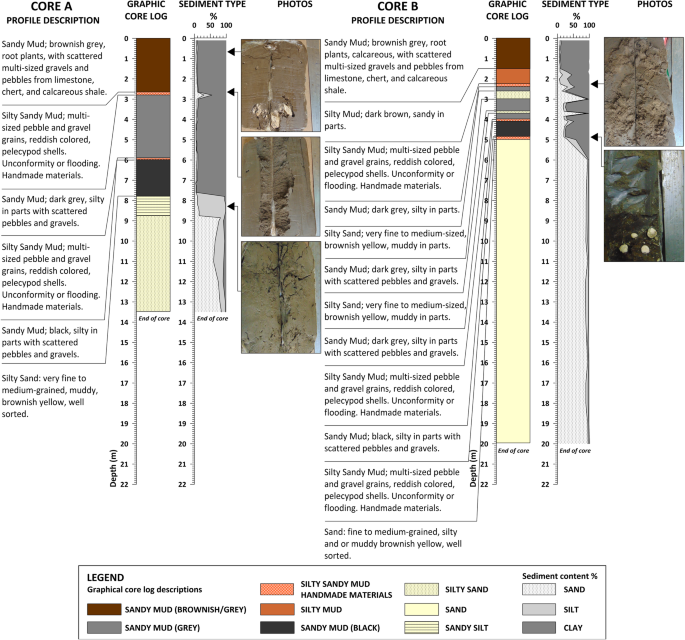

Geophysical surveys using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Electromagnetic Tomography (EMT) along a 1.2 km long profile revealed a hidden river channel lying 1–1.5 m below the cultivated Nile floodplain (Fig. 2 ). The position and shape of this river channel is in an excellent match with those derived from radar satellite imagery for the Ahramat Branch. The EMT profile shows a distinct unconformity in the middle, which in this case indicates sediments that have a different texture than the overlying recent floodplain silt deposits and the sandy sediments that are adjacent to this former branch (Fig. 2 ). GPR overlapping the EMT profile from 600–1100 m on the transect confirms this. Here, we see evidence of an abandoned riverbed approximately 400 m wide and at least 25 m deep (width:depth ratio ~16) at this location. This branch has a symmetrical channel shape and has been infilled with sandy Neonile sediment different to other surrounding Neonile deposits and the underlying Eocene bedrock. The geophysical profile interpretation for the Ahramat Branch at this locality was validated using two sediment cores of depths 20 m (Core A) and 13 m (Core B) (Fig. 3 ). In Core A between the center and left bank of the former branch we found brown sandy mud at the floodplain surface and down to ~2.7 m with some limestone and chert fragments, a reddish sandy mud layer with gravel and handmade material inclusions at ~2.8 m, a gray sandy mud layer from ~3–5.8 m, another reddish sandy mud layer with gravel and freshwater mussel shells at ~6 m, black sandy mud from ~6–8 m, and sandy silt grading into clean, well-sorted medium sand dominated the profile from ~8 to >13 m. In Core B on the right bank of the former branch we found recently deposited brown sandy mud at the floodplain surface and down to ~1.5 m, alternating brown and gray layers of silty and sandy mud down to ~4 m (some reddish layers with gravel and handmade material inclusions), a black sandy mud layer from ~4–4.9 m, and another reddish sandy mud layer with gravel and freshwater mussel shells at ~5 m, before clean, well-sorted medium sand dominated the profile from 5 to >20 m. Shallow groundwater was encountered in both cores concurrently with the sand layers, indicating that the buried sedimentary structure of the abandoned Ahramat Branch acts as a conduit for subsurface water flow beneath the distal floodplain of the modern Nile River.

a Locations of geophysical profile and soil drilling (ESRI World Image Basemap, source: Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics). Photos taken from the field while using the b Electromagnetic Tomography (EMT) and c Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). d Showing the apparent conductivity profile, e showing EMT profile, and f showing GPR profiles with overlain sketch of the channel boundary on the GPR graph. g Simplified interpretation of the buried channel with the location of the two-soil coring of A and B.

It shows two-soil cores, A and core B, with soil profile descriptions, graphic core logs, sediment grain size charts, and example photographs.

Alignment of old and middle kingdom pyramids to the Ahramat Branch

The royal pyramids in ancient Egypt are not isolated monuments, but rather joined with several other structures to form complexes. Besides the pyramid itself, the pyramid complex includes the mortuary temple next to the pyramid, a valley temple farther away from the pyramid on the edge of a waterbody, and a long sloping causeway that connects the two temples. A causeway is a ceremonial raised walkway, which provides access to the pyramid site and was part of the religious aspects of the pyramid itself 19 . In the study area, it was found that many of the causeways of the pyramids run perpendicular to the course of the Ahramat Branch and terminate directly on its riverbank.

In Egyptian pyramid complexes, the valley temples at the end of causeways acted as river harbors. These harbors served as an entry point for the river borne visitors and ceremonial roads to the pyramid. Countless valley temples in Egypt have not yet been found and, therefore, might still be buried beneath the agricultural fields and desert sands along the riverbank of the Ahramat Branch. Five of these valley temples, however, partially survived and still exist in the study area. These temples include the valley temples of the Bent Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure from Dynasty 4; the valley temple of the Pyramid of Sahure from Dynasty 5, and the valley temple of the Pyramid of Pepi II from Dynasty 6. All the aforementioned temples are dated to the Old Kingdom. These five surviving temples were found to be positioned adjacent to the riverbank of the Ahramat Branch, which strongly implies that this river branch was contemporaneously functioning during the Old Kingdom, at the time of pyramid construction.

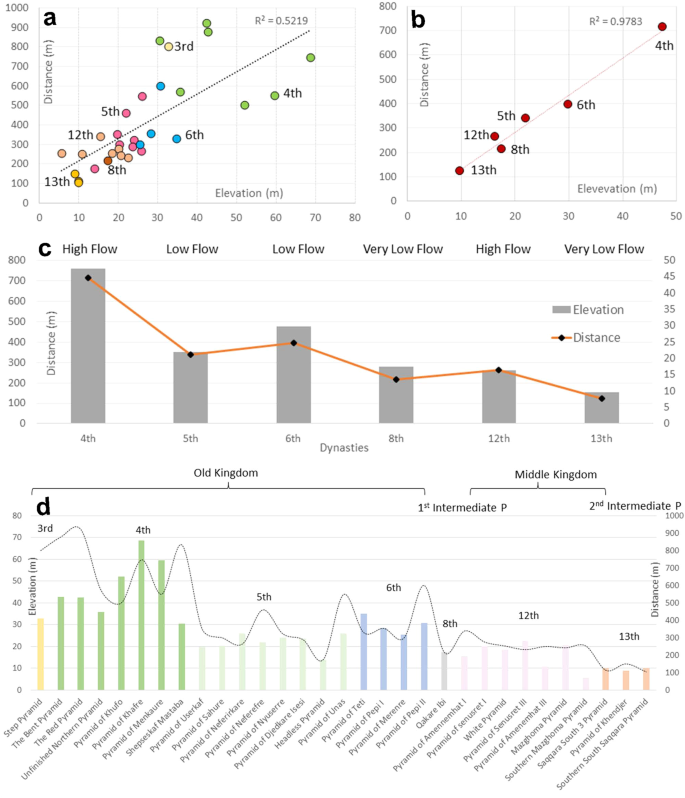

Analysis of the ground elevation of the 31 pyramids and their proximity to the floodplain, within the study area, helped explain the position and relative water level of the Ahramat Branch during the time between the Old Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period (ca. 2649–1540 BCE). Based on Fig. ( 4) , the Ahramat Branch had a high-water level during the first part of the Old Kingdom, especially during Dynasty 4. This is evident from the high ground elevation and long distance from the floodplain of the pyramids dated to that period. For instance, the remote position of the Bent and Red Pyramids in the desert, very far from the Nile floodplain, is a testament to the branch’s high-water level. On the contrary, during the Old Kingdom, our data demonstrated that the Ahramat Branch would have reached its lowest level during Dynasty 5. This is evident from the low altitudes and close proximity to the floodplain of most Dynasty 5 pyramids. The orientation of the Sahure Pyramid’s causeway (Dynasty 5) and the location of its valley temple in the low-lying floodplain provide compelling evidence for the relatively low water level proposition of the Ahramat Branch during this stage. The water level of the Ahramat Branch would have been slightly raised by the end of Dynasty 5 (the last 15–30 years), during the reign of King Unas and continued to rise during Dynasty 6. The position of Pepi II and Merenre Pyramids (Dynasty 6) deep in the desert, west of the Djedkare Isesi Pyramid (Dynasty 5), supports this notion.

It explains the position and relative water level of the Ahramat Branch during the time between the Old Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. a Shows positive correlation between the ground elevation of the pyramids and their proximity to the floodplain. b Shows positive correlation between the average ground elevation of the pyramids and their average proximity to the floodplain in each Dynasty. c Illustrates the water level interpretation by Hassan (1986) in Faiyum Lake in correlation to the average pyramids ground elevation and average distances to the floodplain in each Dynasty. d The data indicates that the Ahramat Branch had a high-water level during the first period of the Old Kingdom, especially during Dynasty 4. The water level reduced afterwards but was raised slightly in Dynasty 6. The position of the Middle Kingdom’s pyramids, which was at lower altitudes and in close proximity to the floodplain as compared to those of the Old Kingdom might be explained by the slight eastward migration of the Ahramat Branch.

In addition, our analysis in Fig. ( 4) , shows that the Qakare Ibi Pyramid of Dynasty 8 was constructed very close to the floodplain on very low elevation, which implies that the Nile water levels were very low at this time of the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BCE). This finding is in agreement with previous work conducted by Kitchen 20 which implies that the sudden collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt (after 4160 BCE) was largely caused by catastrophic failure of the annual flood of the Nile River for a period of 30–40 years. Data from soil cores near Memphis indicated that the Old Kingdom settlement is covered by about 3 m of sand 11 . Accordingly, the Ahramat Branch was initially positioned further west during the Old Kingdom and then shifted east during the Middle Kingdom due to the drought-induced sand encroachments of the First Intermediate Period, “a period of decentralization and weak pharaonic rule” in ancient Egypt, spanning about 125 years (2181–2055 BCE) post Old Kingdom era. Soil cores from the drilling program at Memphis show dominant dry conditions during the First Intermediate Period with massive eolian sand sheets extended over a distance of at least 0.5 km from the edge of the western desert escarpment 21 . The Ahramat Branch continued to move east during the Second Intermediate Period until it had gradually lost most of its water supply by the New Kingdom.

The western tributaries of the Ahramat Branch

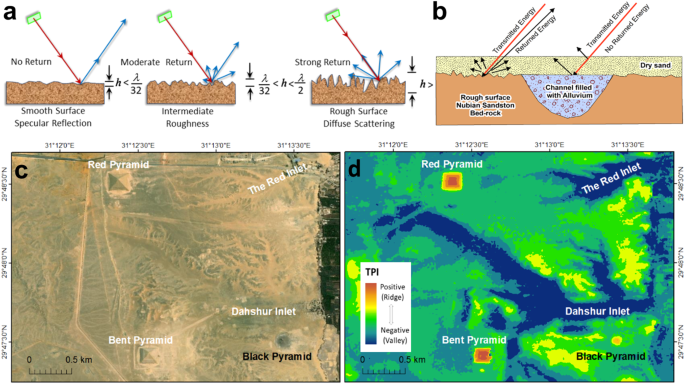

Sentinal-1 radar data unveiled several wide channels (inlets) in the Western Desert Plateau connected to the Ahramat Branch. These inlets are currently covered by a layer of sand, thus partially invisible in multispectral satellite imagery. In Sentinal-1 radar imagery, the valley floors of these inlets appear darker than the surrounding surfaces, indicating subsurface fluvial deposits. These smooth deposits appear dark owing to the specular reflection of the radar signals away from the receiving antenna (Fig. 5a, b ) 22 . Considering that Sentinel-1’s C-Band has a penetration capability of approximately 50 cm in dry sand surface 23 , this would suggest that the riverbed of these channels is covered by at least half a meter of desert sand. Unlike these former inlets, the course of the Ahramat Branch is invisible in SAR data due in large part to the presence of dense farmlands in the floodplain, which limits radar penetration and the detection of underlying fluvial deposition. Moreover, the radar topographic data from TDX revealed the areal extent of these inlets. Their river courses were extracted from TDX data using the Topographic Position Index (TPI), an algorithm which is used to compute the topographic slope positions and to automate landform classifications (Fig. 5c, d ). Negative TPI values show the former riverbeds of the inlets, while positive TPI signify the riverbanks bordering them.

a Conceptual sketch of the dependence of surface roughness on the sensor wavelength λ (modified after 48 ). b Expected backscatter characteristics in sandy desert areas with buried dry riverbeds. c Dry channels/inlets masked by desert sand in the Dahshur area. d The channels’ courses were extracted using TPI. Negative TPI values highlight the courses of the channels while positive TPI signify their banks.

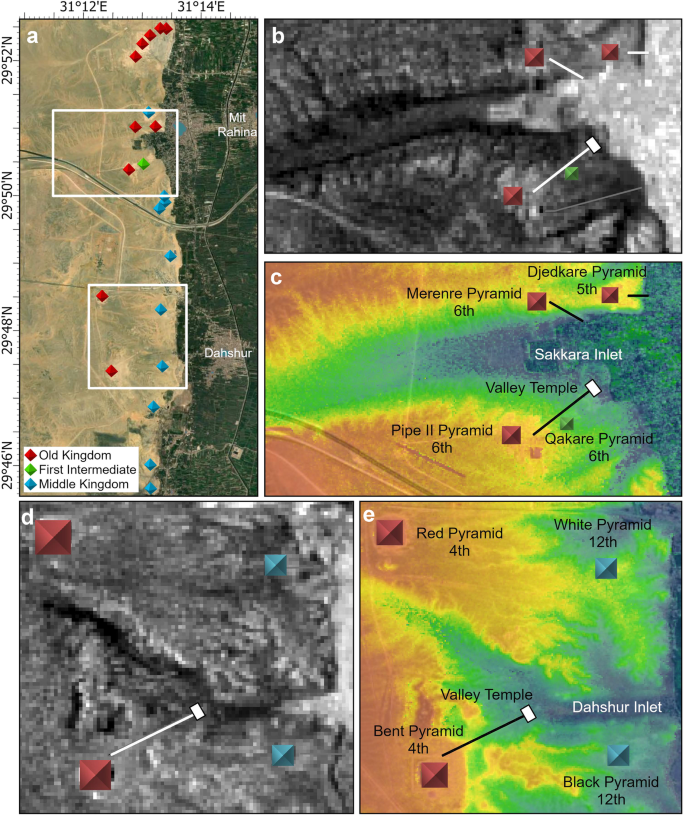

Analysis indicated that several of the pyramid’s causeways, from Dynasties 4 and 6, lead to the inlet’s riverbanks (Fig. 6 ). Among these pyramids, are the Bent Pyramid, the first pyramid built by King Snefru in Dynasty 4 and among the oldest, largest, and best preserved ancient Egyptian pyramids that predates the Giza Pyramids. This pyramid is situated at the royal necropolis of Dahshur. The position of the Bent Pyramid, deep in the desert, far from the modern Nile floodplain, remained unexplained by researchers. This pyramid has a long causeway (~700 m) that is paved in the desert with limestone blocks and is attached to a large valley temple. Although all the pyramids’ valley temples in Egypt are connected to a water body and served as the landing point of all the river-borne visitors, the valley temple of the Bent Pyramid is oddly located deep in the desert, very distant from any waterways and more than 1 km away from the western edge of the modern Nile floodplain. Radar data revealed that this temple overlooked the bank of one of these extinct channels (called Wadi al-Taflah in historical maps). This extinct channel (referred to hereafter as the Dahshur Inlet due to its geographical location) is more than 200 m wide on average (Fig. 6 ). In light of this finding, the Dahshur Inlet, and the Ahramat Branch, are thus strongly argued to have been active during Dynasty 4 and must have played an important role in transporting building materials to the Bent Pyramid site. The Dahshur Inlet could have also served the adjacent Red Pyramid, the second pyramid built by the same king (King Snefru) in the Dahshur area. Yet, no traces of a causeway nor of a valley temple has been found thus far for the Red Pyramid. Interestingly, pyramids in this site dated to the Middle Kingdom, including the Amenemhat III pyramid, also known as the Black Pyramid, White Pyramid, and Pyramid of Senusret III, are all located at least 1 km far to the east of the Dynasty 4 pyramids (Bent and Red) near the floodplain (Fig. 6 ), which once again supports the notion of the eastward shift of the Ahramat Branch after the Old Kingdom.

a The two inlets are presently covered by sand, thus invisible in optical satellite imagery. b Radar data, and c TDX topographic data reveal the riverbed of the Sakkara Inlet due to radar signals penetration capability in dry sand. b and c show the causeways of Pepi II and Merenre Pyramids, from Dynasty 6, leading to the Saqqara Inlet. The Valley Temple of Pepi II Pyramid overlooks the inlet riverbank, which indicates that the inlet, and thus Ahramat Branch, were active during Dynasty 6. d Radar data, and e TDX topographic data, reveal the riverbed of the Dahshur Inlet with the Bent Pyramid’s causeway of Dynasty 4 leading to the Inlet. The Valley Temple of the Bent Pyramid overlooks the riverbank of the Dahshur Inlet, which indicates that the inlet and the Ahramat Branch were active during Dynasty 4 of the Old Kingdom.

Radar satellite data revealed yet another sandy buried channel (tributary), about 6 km north of the Dahshur Inlet, to the west of the ancient city of Memphis. This former fluvial channel (referred to hereafter as the Saqqara Inlet due to its geographical location) connects to the Ahramat Branch with a broad river course of more than 600 m wide. Data shows that the causeways of the two pyramids of Pepi II and Merenre, situated at the royal necropolis of Saqqara and dated to Dynasty 6, lead directly to the banks of the Saqqara Inlet (see Fig. 6 ). The 400 m long causeway of Pepi II pyramid runs northeast over the southern Saqqara plateau and connects to the riverbank of the Saqqara Inlet from the south. The causeway terminates with a valley temple that lies on the inlet’s riverbank. The 250 long causeway of the Pyramid of Merenre runs southeast over the northern Saqqara plateau and connects to the riverbank of the Saqqara Inlet from the north. Since both pyramids dated to Dynasty 6, it can be argued that the water level of the Ahramat Branch was higher during this period, which would have flooded at least the entrance of its western inlets. This indicates that the downstream segment of the Saqqara Inlet was active during Dynasty 6 and played a vital role in transporting construction materials and workers to the two pyramids sites. The fact that none of the Dynasty 5 pyramids in this area (e.g., the Djedkare Isesi Pyramid) were positioned on the Saqqara Inlet suggests that the water level in the Ahramat Branch was not high enough to enter and submerge its inlets during this period.

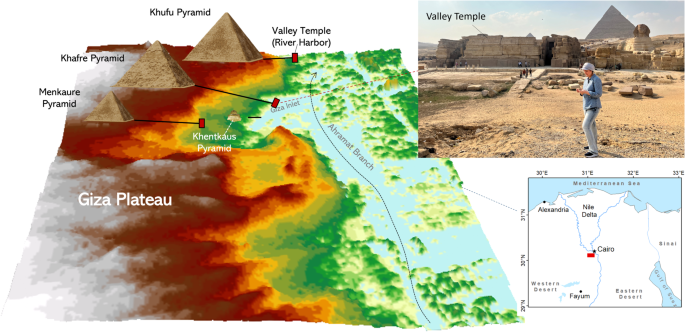

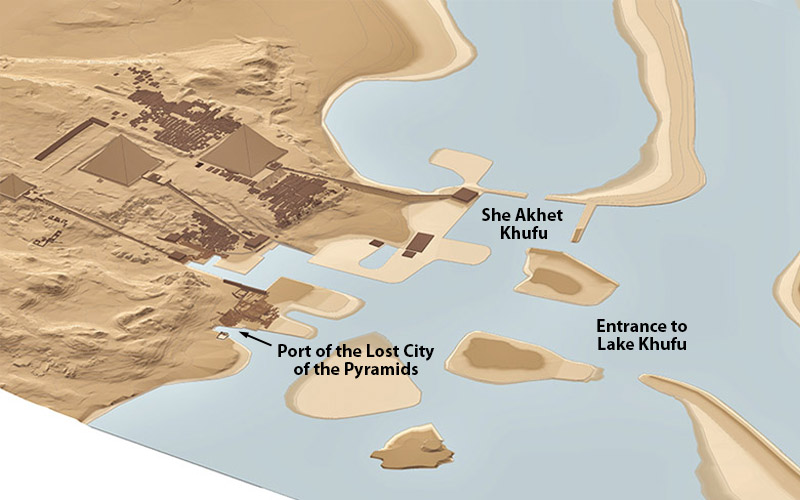

In addition, our data analysis clearly shows that the causeways of the Khafre, Menkaure, and Khentkaus pyramids, in the Giza Plateau, lead to a smaller but equally important river bay associated with the Ahramat Branch. This lagoon-like river arm is referred to here as the Giza Inlet (Fig. 7 ). The Khufu Pyramid, the largest pyramid in Egypt, seems to be connected directly to the river course of the Ahramat Branch (Fig. 7 ). This finding proves once again that the Ahramat Branch and its western inlets were hydrologically active during Dynasty 4 of the Old Kingdom. Our ancient river inlet hypothesis is also in accordance with earlier research, conducted on the Giza Plateau, which indicates the presence of a river and marsh-like environment in the floodplain east of the Giza pyramids 2 .

The causeways of the four Pyramids lead to an inlet, which we named the Giza Inlet, that connects from the west with the Ahramat Branch. These causeways connect the pyramids with valley temples which acted as river harbors in antiquity. These river segments are invisible in optical satellite imagery since they are masked by the cultivated lands of the Nile floodplain. The photo shows the valley temple of Khafre Pyramid (Photo source: Author Eman Ghoneim).

During the Old Kingdom Period, our analysis suggests that the Ahramat Branch had a high-water level during the first part, especially during Dynasty 4 whereas this water level was significantly decreased during Dynasty 5. This finding is in agreement with previous studies which indicate a high Nile discharge during Dynasty 4 (e.g., ref. 24 ). Sediment isotopic analysis of the Nile Delta indicated that Nile flows decrease more rapidly by the end of Dynasty 4 25 , in addition 26 reported that during Dynasties 5 and 6 the Nile flows were the lowest of the entire Dynastic period. This long-lost Ahramat Branch (possibly a former Yazoo tributary to the Nile) was large enough to carry a large volume of the Nile discharge in the past. The ancient channel segment uncovered by 1 , 15 west of the city of Memphis through borehole logs is most likely a small section of the large Ahramat Branch detected in this study. In the Middle Kingdom, although previous studies implied that the Nile witnessed abundant flood with occasional failures (e.g., ref. 27 ), our analysis shows that all the pyramids from the Middle Kingdom were built far east of their Old Kingdom counterparts, on lower altitudes and in close proximity to the floodplain as compared to those of the Old Kingdom. This paradox might be explained by the fact that the Ahramat Branch migrated eastward, slightly away from the Western Desert escarpment, prior to the construction of the Middle Kingdom pyramids, resulting in the pyramids being built eastward so that they could be near the waterway.

The eastward migration and abandonment of the Ahramat Branch could be attributed to gradual tilting of the Nile delta and floodplain in lower Egypt towards the northeast due to tectonic activity 28 . A topographic tilt such as this would have accelerated river movement eastward due to the river being located in the west at a relatively higher elevation of the floodplain. While near-channel floodplain deposition would naturally lead to alluvial ridge development around the active Ahramat Branch, and therefore to lower-lying tracts of adjacent floodplain to the east, regional tilting may explain the wholesale lateral migration of the river in that direction. The eastward migration and abandonment of the branch could also be ascribed to sand incursion due to the branch’s proximity to the Western Desert Plateau, where windblown sand is abundant. This would have increased sand deposition along the riverbanks and caused the river to silt up, particularly during periods of low flow. The region experienced drought during the First Intermediate Period, prior to the Middle Kingdom. In the area of Abu Rawash north 29 and Dahshur site 11 , settlements from the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom were found to be covered by more than 3 m of desert sands. During this time, windblown sand engulfed the Old Kingdom settlements and desert sands extended eastward downhill over a distance of at least 0.5 km 21 . The abandonment of sites at Abusir (5 th Dynasty), where the early pottery-rich deposits are covered by wind-blown sand and then mud without sherds, can be used as evidence that the Ahramat Branch migrated eastward after the Old Kingdom. The increased sand deposition activity, during the end of the Old Kingdom, and throughout the First Intermediate Period, was most likely linked to the period of drought and desertification of the Sahara 30 . In addition, the reduced river discharge caused by decreased rainfall and increased aridity in the region would have gradually reduced the river course’s capacity, leading to silting and abandonment of the Ahramat Branch as the river migrated to the east.

The Dahshur, Saqqara, and Giza inlets, which were connected to the Ahramat Branch from the west, were remnants of past active drainage systems dated to the late Tertiary or the Pleistocene when rainwater was plentiful 31 . It is proposed that the downstream reaches of these former channels (wadis) were submerged during times of high-water levels of the Ahramat Branch, forming long narrow water arms (inlets) that gave a wedge-like shape to the western flank of the Ahramat Branch. During the Old Kingdom, the waters of these inlets would have flowed westward from the Ahramat Branch rather than from their headwaters. As the drought intensified during the First Intermediate Period, the water level of the Ahramat Branch was lowered and withdrew from its western inlets, causing them to silt up and eventually dry out. The Dahshur, Saqqara, and Giza inlets would have provided a bay environment where the water would have been calm enough for vessels and boats to dock far from the busy, open water of the Ahramat Branch.

Sediments from the Ahramat Branch riverbed, which were collected from the two deep soil cores (cores A and B), show an abrupt shift from well-sorted medium sands at depth to overlying finer materials with layers including gravel, shell, and handmade materials. This indicates a step-change from a relatively consistent higher-energy depositional regime to a generally lower-energy depositional regime with periodic flash floods at these sites. So, the Ahramat Branch in this region carried and deposited well-sorted medium sand during its last active phase, and over time became inactive, infilling with sand and mud until an abrupt change led the (by then) shallow depression fill with finer distal floodplain sediment (possibly in a wetland) that was utilized by people and experienced periodic flash flooding. Validation of the paleo-channel position and sediment type using these cores shows that the Ahramat Branch has similar morphological features and an upward-fining depositional sequence as that reported near Giza, where two cores were previously used to reconstruct late Holocene Nile floodplain paleo-environments 2 . Further deep soil coring could determine how consistent the geomorphological features are along the length of the Ahramat branch, and to help explain anomalies in areas where the branch has less surface expression and where remote sensing and geophysical techniques have limitations. Considering more core logs can give a better understanding of the floodplain and the buried paleo-channels.

The position of the Ahramat Branch along the western edge of the Nile floodplain suggests it to be the downstream extension of Bahr Yusef. In fact, Bahr Yusef’s course may have initially flowed north following the natural surface gradient of the floodplain before being forced to turn west to flow into the Fayum Depression. This assumption could be supported by the sharp westward bend of Bahr Yusef’s course at the entrance to the Fayum Depression, which could be a man-made attempt to change the waterflow direction of this branch. According to Römer 32 , during the Middle Kingdom, the Gadallah Dam located at the entrance of the Fayum, and a possible continuation running eastwards, blocked the flow of Bahr Yusef towards the north. However, a sluice, probably located near the village of el-Lahun, was created in order to better control the flow of water into the Fayum. When the sluice was locked, the water from Bahr Yusef was directed to the west and into the depression, and when the sluice was open, the water would flow towards the north via the course of the Ahramat Branch. Today, the abandoned Ahramat Branch north of Fayum appears to support subsurface water flow in the buried coarse sand bed layers, however these shallow groundwater levels are likely to be quite variable due to proximity of the bed layers to canals and other waterways that artificially maintain shallow groundwater. Groundwater levels in the region are known to be variable 33 , but data on shallow groundwater could be used to further validate the delineated paleo-channel of the Ahramat Branch.

The present work enabled the detection of segments of a major former Nile branch running at the foothills of the Western Desert Plateau, where the vast majority of the Ancient Egyptian pyramids lie. The enormity of this branch and its proximity to the pyramid complexes, in addition to the fact that the pyramids’ causeways terminate at its riverbank, all imply that this branch was active and operational during the construction phase of these pyramids. This waterway would have connected important locations in ancient Egypt, including cities and towns, and therefore, played an important role in the cultural landscape of the region. The eastward migration and abandonment of the Ahramat Branch could be attributed to gradual movement of the river to the lower-lying adjacent floodplain or tilting of the Nile floodplain toward the northeast as a result of tectonic activity, as well as windblown sand incursion due to the branch’s proximity to the Western Desert Plateau. The increased sand deposition was most likely related to periods of desertification of the Great Sahara in North Africa. In addition, the branch eastward movement and diminishing could be explained by the reduction of the river discharge and channel capacity caused by the decreased precipitation and increased aridity in the region, particularly during the end of the Old Kingdom.

The integration of radar satellite data with geophysical surveying and soil coring, which we utilized in this study, is a highly adaptable approach in locating similar former buried river systems in arid regions worldwide. Mapping the hidden course of the Ahramat Branch, allowed us to piece together a more complete picture of ancient Egypt’s former landscape and a possible water transportation route in Lower Egypt, in the area between Lisht and the Giza Plateau.

Revealing this extinct Nile branch can provide a more refined idea of where ancient settlements were possibly located in relation to it and prevent them from being lost to rapid urbanization. This could improve the protection measures of Egyptian cultural heritage. It is the hope that our findings can improve conservation measures and raise awareness of these sites for modern development planning. By understanding the landscape of the Nile floodplain and its environmental history, archeologists will be better equipped to prioritize locations for fieldwork investigation and, consequently, raise awareness of these sites for conservation purposes and modern development planning. Our finding has filled a much-needed knowledge gap related to the dominant waterscape in ancient Egypt, which could help inform and educate a wide array of global audiences about how earlier inhabitants were living and in what ways shifts in their landscape drove human activity in such an iconic region.

Materials and methods

The work comprised of two main elements: satellite remote sensing and historical maps and geophysical survey and sediment coring, complemented by archeological resources. Using this suite of investigative techniques provided insights into the nature and relationship of the former Ahramat Branch with the geographical location of the pyramid complexes in Egypt.

Satellite remote sensing and historical maps

Unlike optical sensors that image the land surface, radar sensors image the subsurface due to their unique ability to penetrate the ground and produce images of hidden paleo-rivers and structures. In this context, radar waves strip away the surface sand layer and expose previously unidentified buried channels. The penetration capability of radar waves in the hyper-arid regions of North Africa is well documented 4 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . The penetration depth varies according to the radar wavelength used at the time of imaging. Radar signal penetration becomes possible without significant attenuation if the surface cover material is extremely dry (<1% moisture content), fine grained (<1/5 of the imaging wavelength) and physically homogeneous 23 . When penetrating desert sand, radar signals have the ability to detect subsurface soil roughness, texture, compactness, and dielectric properties 38 . We used the European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-1 data, a radar satellite constellation consisting of a C-Band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensor, operating at 5.405 GHz. The Sentinel-1 SAR image used here was acquired in a descending orbit with an interferometric wide swath mode (IW) at ground resolutions of 5 m × 20 m, and dual polarizations of VV + VH. Since Sentinal-1 is operated in the C-Band, it has an estimated penetration depth of 50 cm in very dry, sandy, loose soils 39 . We used ENVI v. 5.7 SARscape software for processing radar imagery. The used SAR processing sequences have generated geo-coded, orthorectified, terrain-corrected, noise free, radiometrically calibrated, and normalized Sentinel-1 images with a pixel size of 12.5 m. In SAR imagery subsurface fluvial deposits appear dark owing to specular reflection of the radar signals away from the receiving antenna, whereas buried coarse and compacted material, such as archeological remains appear bright due to diffuse reflection of radar signals 40 .

Other previous studies have shown that combining radar topographic imagery (e.g., Shuttle Radar Topography Mission-SRTM) with SAR images improves the extraction and delineation of mega paleo-drainage systems and lake basins concealed under present-day topographic signatures 3 , 4 , 22 , 41 . Topographic data represents a primary tool in investigating surface landforms and geomorphological change both spatially and temporally. This data is vital in mapping past river systems due to its ability to show subtle variations in landform morphology 37 . In low lying areas, such as the Nile floodplain, detailed elevation data can detect abandoned channels, fossilized natural levees, river meander scars and former islands, which are all crucial elements for reconstructing the ancient Nile hydrological network. In fact, the modern topography in many parts of the study area is still a good analog of the past landscape. In the present study, TanDEM-X (TDX) topographic data, from the German Aerospace Centre (DLR), has been utilized in ArcGIS Pro v. 3.1 software due to its fine spatial resolution of 0.4 arc-second ( ∼ 12 m). TDX is based on high frequency X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) (9.65 GHz) and has a relative vertical accuracy of 2 m for areas with a slope of ≤20% 42 . This data was found to be superior to other topographic DEMs (e.g., Shuttle Radar Topography Mission and ASTER Global Digital Elevation Map) in displaying fine topographic features even in the cultivated Nile floodplain, thus making it particularly well suited for this study. Similar archeological investigations using TDX elevation data in the flat terrains of the Seyhan River in Turkey and the Nile Delta 43 , 44 allowed for the detection of levees and other geomorphologic features in unprecedented spatial resolution. We used the Topographic Position Index (TPI) module of 45 with the TDX data by applying varying neighboring radiuses (20–100 m) to compute the difference between a cell elevation value and the average elevation of the neighborhood around that cell. TPI values of zero are either flat surfaces with minimal slope, or surfaces with a constant gradient. The TPI can be computed using the following expression 46 .

Where the scaleFactor is the outer radius in map units and Irad and Orad are the inner and outer radius of annulus in cells. Negative TPI values highlight abandoned riverbeds and meander scars, while positive TPI signify the riverbanks and natural levees bordering them.

The course of the Ahramat Branch was mapped from multiple data sources and used different approaches. For instance, some segments of the river course were derived automatically using the TPI approach, particularly in the cultivated floodplain, whereas others were mapped using radar roughness signatures specially in sandy desert areas. Moreover, a number of abandoned channel segments were digitized on screen from rectified historical maps (Egyptian Survey Department scale 1:50,000 collected on years 1910–1911) near the foothill of the Western Desert Plateau. These channel segments together with the former river course segments delineated from radar and topographic data were aggregated to generate the former Ahramat Branch. In addition to this and to ensure that none of the channel segments of the Ahramat Branch were left unmapped during the automated process, a systematic grid-based survey (through expert’s visual observation) was performed on the satellite data. Here, Landsat 8 and Sentinal-2 multispectral images, Sentinal-1 radar images and TDX topographic data were used as base layers, which were thoroughly examined, grid-square by grid-square (2*2 km per a square) at a full resolution, in order to identify small-scale fluvial landforms, anomalous agricultural field patterns and irregular ditches, and determine their spatial distributions. Here, ancient fluvial channels were identified using two key aspects: First, the sinuous geometry of natural and manmade features and, second the color tone variations in the satellite imagery. For example, clusters of contiguous pixels with darker tones and sinuous shapes may signify areas of a higher moisture content in optical imagery, and hence the possible existence of a buried riverbed. Stretching and edge detection were applied to enhance contrasts in satellite images brightness to enable the visualization of traces of buried river segments that would otherwise go unobserved. Lastly, all the pyramids and causeways in the study site, along with ancient harbors and valley temples, as indicators of preexisting river channels, were digitized from satellite data and available archeological resources and overlaid onto the delineated Ahramat Branch for geospatial analysis.

Geophysical survey and sediment coring

Geophysical measurements using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Electromagnetic Tomography (EMT) were utilized to map subsurface fluvial features and validate the satellite remote sensing findings. GPR is effective in detecting changes of dielectric constant properties of sediment layers, and its signal responses can be directly related to changes in relative porosity, material composition, and moisture content. Therefore, GPR can help in identifying transitional boundaries in subsurface layers. EMT, on the other hand, shows the variations and thickness of large-scale sedimentary deposits and is more useful in clay-rich soil than GPR. In summer 2022, a geophysical profile was measured using GPR and EMT units with a total length of approximately 1.2 km. The GPR survey was conducted with a central frequency antenna of 35 MHz and a trigger interval of 5 cm. The EMT survey was performed using the multi-frequency terrain conductivity (EM–34–3) measuring system with a spacing of 10–11 meters between stations. To validate the remote sensing and geophysical data, two sediment cores with depths of 20 m (Core A) and 13 m (Core B) were collected using a deep soil driller. These cores were collected from along the geophysical profile in the floodplain. Sieving and organic analysis were performed on the sediment samples at Tanta University sediment lab to extract information about grain size for soil texture and total organic carbon. In soil texture analysis medium to coarse sediment, such as sands, are typical for river channel sediments, loamy sand and sandy loam deposits can be interpreted as levees and crevasse splays, whereas fine texture deposits, such as silt loam, silty clay loam, and clay deposits, are representative of the more distal parts of the river floodplain 47 .

Data availability

Data for replicating the results of this study are available as supplementary files at: https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Pyramids_Elevations_and_Distances_xlsx/25216259 .

Bunbury, J., Tavares, A., Pennington, B. & Gonçalves, P. Development of the Memphite Floodplain: Landscape and Settlement Symbiosis in the Egyptian Capital Zone. In The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in Egypt (eds. Willems, H. & Dahms, J.-M.) 71–96 (Transcript Verlag, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839436158-003 .

Sheisha, H. et al. Nile waterscapes facilitated the construction of the Giza pyramids during the 3rd millennium BCE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 , e2202530119 (2022).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ghoneim, E. & El-Baz, F. K. DEM‐optical‐radar data integration for palaeohydrological mapping in the northern Darfur, Sudan: implication for groundwater exploration. Int. J. Remote Sens. 28 , 5001–5018 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ghoneim, E., Benedetti, M. M. & El-Baz, F. K. An integrated remote sensing and GIS analysis of the Kufrah Paleoriver, Eastern Sahara. Geomorphology 139 , 242–257 (2012).

Zaki, A. S. et al. Did increased flooding during the African Humid Period force migration of modern humans from the Nile Valley? Quat. Sci. Rev. 272 , 107200 (2021).

Rohling, E. J., Marino, G. & Grant, K. M. Mediterranean climate and oceanography, and the periodic development of anoxic events (sapropels). Earth Sci. Rev. 143 , 62–97 (2015).

DeMenocal, P. et al. Abrupt onset and termination of the African Humid Period: rapid climate responses to gradual insolation forcing. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19 , 347–361 (2000).

Ritchie, J. C. & Haynes, C. V. Holocene vegetation zonation in the eastern Sahara. Nature 330 , 645–647 (1987).

Butzer, K. W. Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt: A Study in Cultural Ecology (The University of Chicago press, Chicago [Ill.] London, 1976).

Kröpelin, S. et al. Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years. Science 320 , 765–768 (2008).

Bunbury, J. & Jeffreys, D. Real and Literary Landscapes in Ancient Egypt. Camb. Archaeol. J. 21 , 65–76 (2011).

Sterling, S. Mortality Profiles as Indicators of Slowed Reproductive Rates: Evidence from Ancient Egypt. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 18 , 319–343 (1999).

Hillier, J. K., Bunbury, J. M. & Graham, A. Monuments on a migrating Nile. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34 , 1011–1015 (2007).

Bunbury, J. & Lutley, K. The Nile on the move. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:131474399 (2008).

Hassan, F. A., Hamdan, M. A., Flower, R. J., Shallaly, N. A. & Ebrahem, E. Holocene alluvial history and archaeological significance of the Nile floodplain in the Saqqara-Memphis region, Egypt. Quat. Sci. Rev. 176 , 51–70 (2017).

Bietak, M., Czerny, E. & Forstner-Müller, I. Cities and urbanism in ancient Egypt . Papers from a workshop in November 2006 at the Austrian Academy of Sciences (Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2010).

El-Qady, G., Shaaban, H., El-Said, A. A., Ghazala, H. & El-Shahat, A. Tracing of the defunct Canopic Nile branch using geoelectrical resistivity data around Itay El-Baroud area, Nile Delta, Egypt. J. Geophys. Eng. 8 , 83–91 (2011).

Toonen, W. H. J. et al. Holocene fluvial history of the Nile’s west bank at ancient Thebes, Luxor, Egypt, and its relation with cultural dynamics and basin-wide hydroclimatic variability. Geoarchaeology 33 , 273–290 (2018).

Lehner, M. The Complete Pyramids (Thames and Hudson, New York, 1997).

Kitchen, K. A. The chronology of ancient Egypt. World Archaeol. 23 , 201–208 (1991).

Giddy, L. & Jeffreys, D. Memphis, 1991. J. Egypt. Archaeol. 78 , 1–11 (1992).

Ghoneim, E., Robinson, C. & El‐Baz, F. Radar topography data reveal drainage relics in the eastern Sahara. Int. J. Remote Sens. 28 , 1759–1772 (2007).

Roth, L. & Elachi, C. Coherent electromagnetic losses by scattering from volume inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 23 , 674–675 (1975).

Hassan, F. A. Holocene lakes and prehistoric settlements of the Western Faiyum, Egypt. J. Archaeol. Sci. 13 , 483–501 (1986).

Woodward, J. C., Macklin, M. G., Krom, M. D. & Williams, M. A. J. The Nile: Evolution, Quaternary River Environments and Material Fluxes. In Large Rivers (ed. Gupta, A.) 261–292 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470723722.ch13 .

Krom, M. D., Stanley, J. D., Cliff, R. A. & Woodward, J. C. Nile River sediment fluctuations over the past 7000 yr and their key role in sapropel development. Geology 30 , 71–74 (2002).

Stanley, J.-D., Krom, M. D., Cliff, R. A. & Woodward, J. C. Short contribution: Nile flow failure at the end of the Old Kingdom, Egypt: Strontium isotopic and petrologic evidence. Geoarchaeology 18 , 395–402 (2003).

Stanley, D. J. & Warne, A. G. Nile Delta: Recent Geological Evolution and Human Impact. Science 260 , 628–634 (1993).

Jones, M. A new old Kingdom settlement near Ausim: report of the archaeological discoveries made in the Barakat drain improvements project, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:194486461 (1995).

Bunbury, J. M. The development of the River Nile and the Egyptian Civilization: A Water Historical Perspective with Focus on the First Intermediate Period. In A History of Water: Rivers and Society — From the Birth of Agriculture to Modern Times , Vol. 2 (eds. Tvedt, T. & Coopey, R) 50–69 (I.B. Tauris, 2010).

Bubenzer, O. & Riemer, H. Holocene climatic change and human settlement between the central Sahara and the Nile Valley: Archaeological and geomorphological results. Geoarchaeology 22 , 607–620 (2007).

Römer, C. The Nile in the Fayum: Strategies of Dominating and Using the Water Resources of the River in the Oasis in the Middle Kingdom and the Graeco-Roman Period. In The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in Egypt (eds. Willems, H. & Dahms, J.-M.) 171–192 (transcript Verlag, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839436158-006 .

Mansour, K. et al. Investigation of Groundwater Occurrences Along the Nile Valley Between South Cairo and Beni Suef, Egypt, Using Geophysical and Geodetic Techniques. Pure Appl. Geophys. 180 , 3071–3088 (2023).

McCauley, J. F. et al. Subsurface Valleys and Geoarcheology of the Eastern Sahara Revealed by Shuttle Radar. Science 218 , 1004–1020 (1982).

El-Baz, F. & Robinson, C. A. Paleo-channels revealed by SIR-C data in the Western Desert of Egypt: Implications to sand dune accumulations. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Applied Geologic Remote Sensing , Vol. 1, I–469 (Environmental Research Institute of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1997).

Robinson, C. A., El-Baz, F., Al-Saud, T. S. M. & Jeon, S. B. Use of radar data to delineate palaeodrainage leading to the Kufra Oasis in the eastern Sahara. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 44 , 229–240 (2006).

Ghoneim, E. Rimaal: A Sand Buried Structure of Possible Impact Origin in the Sahara: Optical and Radar Remote Sensing Investigation. Remote Sens. 10 , 880 (2018).

Ghoneim, E. M. Ibn-Batutah: A possible simple impact structure in southeastern Libya, a remote sensing study. Geomorphology 103 , 341–350 (2009).

Schaber, G. G., Kirk, R. L. & Strom, R. Data base of impact craters on Venus based on analysis of Magellan radar images and altimetry data. U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report, https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr98104 , https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1998/0104/report.pdf (1998).

Ghoneim, E. & El-Baz, F. K. Satellite Image Data Integration for Groundwater Exploration in Egypt, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:216495993 (2020).

Skonieczny, C. et al. African humid periods triggered the reactivation of a large river system in Western Sahara. Nat. Commun. 6 , 8751 (2015).

Wessel, B. et al. Accuracy assessment of the global TanDEM-X Digital Elevation Model with GPS data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 139 , 171–182 (2018).

Erasmi, S., Rosenbauer, R., Buchbach, R., Busche, T. & Rutishauser, S. Evaluating the Quality and Accuracy of TanDEM-X Digital Elevation Models at Archaeological Sites in the Cilician Plain, Turkey. Remote Sens. 6 , 9475–9493 (2014).

Ginau, A., Schiestl, R. & Wunderlich, J. Integrative geoarchaeological research on settlement patterns in the dynamic landscape of the northwestern Nile delta. Quat. Int. 511 , 51–67 (2019).

JENNESS, J. Topographic position index (tpi_jen.avx_extension for Arcview 3.x, v.1.3a, Jenness Enterprises [EB/OL], http://www.jennessent.com/arcview/tpi.htm (2006).

Weiss, A. D. Topographic position and landforms analysis, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:131349144 (2001).

Verstraeten, G., Mohamed, I., Notebaert, B. & Willems, H. The Dynamic Nature of the Transition from the Nile Floodplain to the Desert in Central Egypt since the Mid-Holocene. In The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in Egypt (eds. Willems, H. & Dahms, J.-M.) 239–254 (transcript Verlag, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839436158-009 .

Meyer, F. Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar: Principles, data access, and basic processing techniques. In Synthetic Aperture Radar the SAR Handbook: Comprehensive Methodologies for Forest Monitoring and Biomass Estimation. 21–64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.25966/nr2c-s697 , https://gis1.servirglobal.net/TrainingMaterials/SAR/SARHB_FullRes.pdf .

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NSF grant # 2114295 awarded to E.G., S.O. and T.R. and partially supported by Research Momentum Fund, UNCW, to E.G. TanDEM-X data was awarded to E.G. and R.E by the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) (contract # DEM_OTHER2886). Permissions for collecting soil coring and sampling were obtained from the Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Egypt by coauthors Dr. Amr Fhail and Dr. Mohamed Fathy. Bradley Graves at Macquarie University assisted with preparation of the sedimentological figures. Hamada Salama at NRIAG assisted with the GPR field data collection.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, NC, 28403-5944, USA

Eman Ghoneim

School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University, Macquarie, NSW, 2109, Australia

Timothy J. Ralph

Department of History, The University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, 38152-3450, USA

Suzanne Onstine

Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 60637, USA

Raghda El-Behaedi

National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics (NRIAG), Helwan, Cairo, 11421, Egypt

Gad El-Qady, Mahfooz Hafez, Magdy Atya, Mohamed Ebrahim & Ashraf Khozym

Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Tanta, 31527, Egypt

Amr S. Fahil & Mohamed S. Fathy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Eman Ghoneim conceived the ideas, lead the research project, and conducted the data processing and interpretations. The manuscript was written and prepared by Eman Ghoneim. Timothy J. Ralph co-supervised the project, contributed to the geomorphological and sedimentological interpretations, edited the manuscript and the figures. Suzanne Onstine co-supervised the project, contributed to the archeological and historical interpretations, and edited the manuscript. Raghda El-Behaedi contributed to the remote sensing data processing and methodology and edited the manuscript. Gad El-Qady supervised the geophysical survey. Mahfooz Hafez, Magdy Atya, Mohamed Ebrahim, Ashraf Khozym designed, collected, and interpreted the GPR and EMT data. Amr S. Fahil and Mohamed S. Fathy supervised the soil coring, sediment analysis, drafted sedimentological figures and contributed to the interpretations. All authors reviewed the manuscript and participated in the fieldwork.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eman Ghoneim .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Ritambhara Upadhyay and Judith Bunbury for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Patricia Spellman and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Peer review file, supplementary information file, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ghoneim, E., Ralph, T.J., Onstine, S. et al. The Egyptian pyramid chain was built along the now abandoned Ahramat Nile Branch. Commun Earth Environ 5 , 233 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01379-7

Download citation

Received : 06 December 2023

Accepted : 10 April 2024

Published : 16 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01379-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Saudi J Biol Sci

- v.28(10); 2021 Oct

Traditional ancient Egyptian medicine: A review

Ahmed m. metwaly.

a Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Al-Azhar University, Cairo 11371, Egypt

Mohammed M. Ghoneim

b Department of Pharmacy Practice, College of Pharmacy, AlMaarefa University, Ad Diriyah, Riyadh 13713, Saudi Arabia

Ibrahim.H. Eissa

c Pharmaceutical Medicinal Chemistry & Drug Design Department, Faculty of Pharmacy (Boys), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Islam A. Elsehemy

d Department of Natural and Microbial Products Chemistry, Division of Pharmaceutical and Drug Industries Research, National Research Center, Cairo, Egypt

Ahmad E. Mostafa

Mostafa m. hegazy, wael m. afifi, deqiang dou.

e College of Pharmacy, Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 77 Life One Road, Dalian Economic and Technical Development Zone, Dalian 116600, China

The ancient Egyptians practiced medicine with highly professional methods. They had advanced knowledge of anatomy and surgery. Also, they treated a lot of diseases including dental, gynecological, gastrointestinal, and urinary disorders. They could diagnose diabetes and cancer. The used therapeutics extended from different plants to include several animal products and minerals. Some of these plants are still used in the present day. Fortunately, they documented their life details by carving on stone, clay, or papyri. Although a lot of these records have been lost or destroyed, the surviving documents represent a huge source of knowledge in different scientific aspects including medicine. This review article is an attempt to understand some information about traditional medicine in ancient Egypt, we will look closely at some basics, sources of information of Egyptian medicine in addition to common treated diseases and therapeutics in this great civilization.

1. Introduction

According to WHO traditional medicine can be defined to be the sum of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether used in health maintenance as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement, or treatment of physical and mental illness ( WHO, 2018 ).

The Egyptian civilization extended for centuries along the sides of the Nile River in the place which is now the country Egypt as one of the greatest and oldest civilizations in the history of humankind, it was renowned for its remarkable achievements in several fields including arts, science, and medicine ( Kemp, 2007 ). Ancient Egypt (3300BCE to 525BCE) is where the first dawn of modern medical care has been found, including bone setting, dentistry, simple surgery, and the use of different sets of medicinal pharmacopeias ( Nunn, 2002 ). The first mention of a physician in history is back to 3533BCE, at that time it was documented that Sekhet'enanch, chief physician healed the Pharaoh Sahura of the fifth dynasty from a disease in his nostrils ( Withington, 1894 ). Documentation of the use of malachite in ancient Egypt as an eye paint and treatment around 4000BCE has been found ( Žuškin et al., 2008 ). Imhotep (2780BCE) was the most famous of early Egyptian physicians, Imhotep was the chief vizier to the pharaoh Zoser, who was the first king of the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Additionally, he was known as the engineer of the step pyramid at Sakkara ( Cormack, 1965 ). Some pictures carved on the door-posts of a tomb in Memphis may be considered as the earliest known pictures of surgical operations (2500B. C.) ( Garrison, 1921 ).

Herodotus (The father of History), about 450BCE, wrote about Egyptians: 'The practice of medicine is so divided among them, that each physician is a healer of one disease and no more. All the country is full of physicians, some of the eye, some of the teeth, some of what pertains to the belly, and some of the hidden diseases' ( Todd, 1921b ).

2. Some basic concepts about traditional ancient Egyptian medicine

Ancient Egyptians did not have a clear dichotomy between both medicine and magic, they considered health and illness resulted from a person’s relationship with the universe including people, animals, good and bad spirits ( Zucconi, 2007 ).

The basic concept of health and disease according to the Ebers Papyrus is that the body has twenty-two mtw (vessels) which connect the body carrying various substances such as blood, air, semen, mucus, and tears. These mtw (vessels) are linked up at some junctures, controlled by the heart, and opened to the outside from several points like an anus. Egyptian healers should determine the condition of mtw -vessels by examination of the patient’s pulse. The balance ( maat ) of this movement is vital for human health just like the balance of the Nile flooding and irrigating is vital for Egypt. If the mtw -vessels were blocked by foreign or noxious matters ( wekhedu ), the disease takes place. These matters may enter the patient’s body through wounds or natural openings ( Veiga, 2009 , Zucconi, 2007 ).

Medical practice was rigidly prescribed by the Hermetic Books of Thoth, and if a patient died as a result of a deviation from this strict line of treatment, it was regarded as a capital crime, if the patient didn’t improve after four days of treatment, physicians were allowed to modify the treatment ( Garrison, 1921 ). There was a hierarchy of medical profession starting with the 'swnw' (ordinary doctor); 'imyr swnw' (overseer of doctors); 'wr swnw' (chief of doctors); 'smsw swnw' (eldest of doctors); and 'shd swnw' (inspector of doctors) ( Reeves, 1992 , Sullivan, 1995 ), there is also evidence proved the existence of women physicians ( Willerson and Teaff, 1996a ).

Ancient Egyptians got a surprising knowledge about anatomy, a lot of diseases of the osseous, alimentary, respiratory, circulatory, genital, muscular, nervous, ocular, auditory, and olfactory systems were described in details, They identified the function of the heart, and its relation to the two types of blood vessels, in addition, cerebrospinal fluid was known to them too ( El-Assal, 1972 ). They wrongly thought that the heart was the center for all body fluids including urine and tears ( Ja, 1962 ).

The surgery in ancient Egyptian was so advanced, surgeons used various instruments similar to what we using today such as the scalpel, forceps, and scissors, splints were made of reeds tied together by strips of linen or pieces of wood padded with plant fibers ( Reeves, 1992 , Saber, 2010 ). They sutured wounds, stopped bleeding using cautery ( Reeves, 1992 , Saber, 2010 ). Boils, abscesses, and septic wounds were opened surgically and drained by pieces of linen, and poultices were used as well ( Sipos et al., 2004 , Todd, 1921a ). A dislocated shoulder was treated in a similar way to the Kocher method, also a dislocated mandible was reduced by the method used today ( Sullivan, 1996 ). The plaster used for fractures consisted of linen soaked in a sticky material which hardened, They made circumcision a lot and there are some reports documented a surgical treatment of a hernia ( Ja, 1962 , Saber, 2010 ).

They knew psychology; Diodorus reported that it was written over the library of the Ramesseum “ Healing Place of the Soul ”. The patient suggested to write his troubles in a letter to dead relatives (catharsis), also there were some specialists in dream interpretation ( El-Assal, 1972 ). In most cases, doctors prescribe a remedy of different drugs, not a single drug. The routes of drug administration were basically five; oral, rectal, vaginal, topical, and fumigation. Treatments were given in different forms like; pills, cakes, ointments, eye drops, gargles, suppositories, fumigations, and baths ( Bryan, 1930 ).

3. Ancient Egyptian medical papyri

Pharaohs documented day after day events using hieroglyphic language by carving on walls of temples, stones, clay, or papyri ( Baines, 1983 ). The translation of the Rosetta stone in 1822, gave an excellent chance to translate several ancient Egyptian papyri including medical papyri ( Parkinson et al., 1999 ). The language which was used for writing on papyri is mostly the hieratic, which was written from the right side to left, using red ink for the headings and black ink for the bulk. Papyrus made from Cyperus papyrus by split interweaving, pounding in water, and drying to form brownish sheets then being written with brush and ink, and finally glued at edges, making a roll ( Baines, 1983 ).

The ancient Egyptian medical papyri documented several details about the way by which they practiced medicine. The papyri describe in-depth the diseases, how to diagnose, and different remedies that were used to treat. These remedies included herbal remedies, sometimes surgery, and even magical spells. ( Leake, 1952 ). Starting from the Middle Kingdom, about 1800 to 300BCE, the remains of more than 40 papyri describing the medical procedures that used to treat various illnesses have explored ( Pommerening, 2012 ).

Most of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian traditional medicine was originated from the ancient Egyptian medical papyri includes Ebers papyrus, Edwin Smith papyrus, Kahun Papyrus, Ramesseum medical papyri, Hearst papyrus, London Medical Papyrus, Brugsch Papyrus, Carlsberg papyrus, Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus, Brooklyn Papyrus, Erman Papyrus, and Leiden Papyrus, the most important eight papyri are listed in table 1 .

Chief Medical Papyri of ancient Egypt.

4. Kahun gynecological papyrus

The text contains 34 sections that deal with gynecology, contraception, and conception techniques ( Haimov-Kochman et al., 2005 ). All of the treatments in the Kahun Papyrus are non-surgical, varied, and interesting including fumigation, massage, and medicines introduced into the body in the form of pessaries or as a liquid to be drunk or rubbed on the skin. Eyes and the womb are, for some reason, closely linked in ancient Egyptian health and medicine ( Stevens, 1975 ). The papyrus discusses each case as the following; a brief description of the symptoms, then the physician is advised how to tell the patient her diagnosis and, finally, treatment is suggested ( Smith, 2011 ). In order to prevent pregnancy (conception), the papyrus recommends excrement (not identified for sure) of crocodile dispersed in honey or sour milk with a pinch of natron (sodium carbonate decahydrate) and injected into the vagina ( Griffith and Petrie, 1898 , Reeves, 1992 ).

5. The Edwin Smith papyrus

This papyrus was named after the man who purchased it in 1862 from a dealer. It is a very old medical text dating back to 1600BCE, it’s about surgical trauma discussing 62 diseases and surgery cases, just fourteen cases with known treatments, maybe because other cases are chronic diseases difficult to treat or even unknown ( Veiga, 2009 ). It has seventeen pages documenting head, neck, and arms injuries in addition to detailing a diagnosis, prognosis, and cause of the trauma ( van Middendorp et al., 2010 ). The treatments included the closure of wounds using sutures, prevent and treat infection with honey and stop bleeding using raw meat. The papyrus recommends immobilizing the head and neck in the case of its injuries in addition to some detailed anatomical observations ( Brandt-Rauf and Brandt-Rauf, 1987 , Breasted, 1930 ). Six cases of spinal injuries were documented in the papyrus, diagnosed with a specific description of symptoms in addition to the clear description for the treatment of three cases of them ( van Middendorp et al., 2010 ).

6. The Ebers papyrus

The famous Ebers Papyrus has been written in 1550BCE using 328 different ingredients (most of them are derived from plant species) to make 876 prescriptions ( Bryan, 1930 ). It’s the longest medical papyrus (68 feet in length and 12 in. in width) and the most complete surviving one, being an encyclopedia of medicine discussing details of a huge number of prescriptions and treatments for a wide variety of diseases that were in vogue among Egyptians of the eighteenth dynasty (c. 1630–1350BCE) including helminthiasis, ophthalmology, dermatology, gynecology, obstetrics, dentistry, and surgery. There is a short section on psychiatry, describing a “despondency” which may be similar to depression in our concept, besides, more than 700 magical formulas were described ( Subbarayappa, 2001 ).

7. The Hearst medical papyrus

The Hearst Papyrus, found in a house made of mud-brick in a provincial town, it’s thought to be a reference for a local physician, and, less carefully organized than Ebers, seems to have been made for this very purpose. The Hearst papyrus contains several remedies including; six remedies related to purging, eight remedies relating to teeth and bones, seven remedies relating to pains, eleven remedies relating to digestion, ten remedies relating to the urinary organs, seven remedies related to head diseases, thirty remedies relating to the vessels, eight remedies relating to the blood, thirteen remedies relating to the hair, the skin, thirty-six remedies relating to fingers and toes, eighteen remedies relating to broken bones, seven or more remedies concerning bites in addition to two incantations and twelve remedies against unidentified diseases ( Bryan, 1930 , Leake, 1952 ).

8. The Berlin papyrus