- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- The covid-19 lab leak...

The covid-19 lab leak hypothesis: did the media fall victim to a misinformation campaign?

Read our latest coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Related content

- Peer review

This article has a correction. Please see:

- The covid-19 lab leak hypothesis: did the media fall victim to a misinformation campaign? - July 12, 2021

- Paul D Thacker , investigative journalist

- thackerpd{at}gmail.com Twitter @thackerpd

The theory that SARS-CoV-2 may have originated in a lab was considered a debunked conspiracy theory, but some experts are revisiting it amid calls for a new, more thorough investigation. Paul Thacker explains the dramatic U turn and the role of contemporary science journalism

For most of 2020, the notion that SARS-CoV-2 may have originated in a lab in Wuhan, China, was treated as a thoroughly debunked conspiracy theory. Only conservative news media sympathetic to President Donald Trump and a few lonely reports dared suggest otherwise. But that all changed in the early months of 2021, and today most outlets across the political spectrum agree: the “lab leak” scenario deserves serious investigation.

Understanding this dramatic U turn on arguably the most important question for preventing a future pandemic, and why it took nearly a year to happen, involves understanding contemporary science journalism.

A conspiracy to label critics as conspiracy theorists

Scientists and reporters contacted by The BMJ say that objective consideration of covid-19’s origins went awry early in the pandemic, as researchers who were funded to study viruses with pandemic potential launched a campaign labelling the lab leak hypothesis as a “conspiracy theory.”

A leader in this campaign has been Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, a non-profit organisation given millions of dollars in grants by the US federal government to research viruses for pandemic preparedness. 1 Over the years EcoHealth Alliance has subcontracted out its federally supported research to various scientists and groups, including around $600 000 (£434 000; €504 000) to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. 1

Shortly after the pandemic began, Daszak effectively silenced debate over the possibility of a lab leak with a February 2020 statement in the Lancet . 2 “We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that covid-19 does not have a natural origin,” said the letter, which listed Daszak as one of 27 coauthors. Daszak did not respond to repeated requests for comment from The BMJ .

“It’s become a label you pin on something you don’t agree with,” says Nicholas Wade, a science writer who has worked at Nature , Science , and the New York Times . “It’s ridiculous, because the lab escape scenario invokes an accident, which is the opposite of a conspiracy.”

But the effort to brand serious consideration of a lab leak a “conspiracy theory” only ramped up. Filippa Lentzos, codirector of the Centre for Science and Security Studies at King’s College, London, told the Wall Street Journal , “Some of the scientists in this area very quickly closed ranks.” 3 She added, “There were people that did not talk about this, because they feared for their careers. They feared for their grants.”

Daszak had support. After he wrote an essay for the Guardian in June 2020 attacking the former head of MI6 for saying that the pandemic could have “started as an accident,” Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust and co-signer of the Lancet letter, promoted Daszak’s essay on Twitter, saying that Daszak was “always worth reading.” 4

Daszak’s behind-the-scenes role in orchestrating the statement in the Lancet came to light in November 2020 in emails obtained through freedom of information requests by the watchdog group US Right To Know.

“Please note that this statement will not have EcoHealth Alliance logo on it and will not be identifiable as coming from any one organization or person,” wrote Daszak in a February email, while sending around a draft of the statement for signatories. 5 In another email, Daszak considered removing his name from the statement “so it has some distance from us and therefore doesn’t work in a counterproductive way.” 6

Several of the 27 scientists who signed the letter Daszak circulated did so using other professional affiliations and omitted reporting their ties to EcoHealth Alliance. 3

For Richard Ebright, professor of molecular biology at Rutgers University in New Jersey and a biosafety expert, scientific journals were complicit in helping to shout down any mention of a lab leak. “That means Nature , Science , and the Lancet ,” he says. In recent months he and dozens of academics have signed several open letters rejecting conspiracy theory accusations and calling for an open investigation of the pandemic’s origins. 7 8 9

“It’s very clear at this time that the term ‘conspiracy theory’ is a useful term for defaming an idea you disagree with,” says Ebright, referring to scientists and journalists who have wielded the term. “They have been successful until recently in selling that narrative to many in the media.”

The Lancet ’s editor in chief, Richard Horton, did not respond to repeated requests for comment but, after The BMJ had sent him questions, the Lancet expanded Daszak’s conflicts of interest on the February statement and recused him from working on its task force looking into the pandemic’s origin. 10 11

The Lancet letter ultimately helped to guide almost a year of reporting, as journalists helped to amplify Daszak’s message and to silence scientific and public debate. “We’re in the midst of the social media misinformation age, and these rumours and conspiracy theories have real consequences,” Daszak told Science . 12 Months later in Nature , he again criticised “conspiracies” that the virus could have come from the Wuhan Institute of Virology and complained about “politically motivated organisations” requesting his emails. 13

That summer Scientific American , one of the oldest and best known popular science magazines in America, published a complimentary profile of Daszak’s colleague, Shi Zhengli, a centre director at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which has been funded by EcoHealth Alliance. 14

EcoHealth Alliance and the Wuhan Institute of Virology earned additional sympathetic reporting after the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) cancelled its grant to EcoHealth Alliance in April last year—allegedly on President Trump’s order—because of its ties to Wuhan, a decision protested by 77 Nobel laureates and 31 scientific societies. 15 (The NIH has subsequently awarded EcoHealth Alliance new funding.)

Efforts to characterise the lab leak scenario as unworthy of serious consideration were far reaching, sometimes affecting reporting that had first appeared well before the covid-19 pandemic. For example, in March 2020 Nature Medicine added an editor’s note (“Scientists believe that an animal is the most likely source of the coronavirus”) to a 2015 paper on the creation of a hybrid version of a SARS virus, co-written by Shi. 16

Wade explains, “Science journalists differ a lot from other journalists in that they are far less sceptical of their sources and they see their main role as simply to explain science to the public.” This, he says, is why they began marching in unison behind Daszak.

By the end of 2020, just a handful of journalists had dared to seriously discuss the possibility of a lab leak. In September, Boston magazine reported on a preprint that found the virus unlikely to have come from the Wuhan seafood market, as Daszak has argued, and that it seemed too well adapted to humans to have arisen naturally. However, the story failed to garner much attention, similarly to a little noticed investigative report by the Associated Press in December that exposed how the Chinese government was clamping down on research into covid-19’s origins.

In January this year, New York magazine ran a sprawling story detailing how the pandemic could have started with a leak from the lab in Wuhan. The hypothetical scenario: “SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes covid-19, began its existence inside a bat, then it learned how to infect people in a claustrophobic mine shaft, and then it was made more infectious in one or more laboratories, perhaps as part of a scientist’s well-intentioned but risky effort to create a broad-spectrum vaccine.” Scientists and their media allies swiftly criticised the article.

But mainstream outlets from the New York Times to the Washington Post are now treating the lab leak hypothesis as a worthy question, one to be answered with a serious investigation. In a recent interview with the New York Times , Shi denied that her lab was ever involved in “gain of function” experiments ( box 1 ) that enhance a virus’s virulence. But the newspaper reported that her lab had been involved in experiments that altered the transmissibility of viruses, alongside interviews with scientists who said that far more transparency was necessary to determine the truth of SARS-CoV-2’s origins. 17

What is “gain of function” research?

After two teams genetically tweaked the H5N1 avian flu virus in 2011 to make it more transmissible in mammals, biosafety experts voiced concerns about “gain of function” research—experimental research that involves altering microbes in ways that change their transmissibility, pathogenicity, or host range.

In the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 2012, Lynn Klotz predicted an 80% chance that a leak of a potential pandemic pathogen would occur sometime in the next 12 years. Two years later a Harvard epidemiologist, Marc Lipsitch, founded the Cambridge Working Group to lobby against such experiments.

At that time, three safety lapses involving dangerous pathogens led to a safety crackdown at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lipsitch later argued in 2018 that the release of such a pathogen would “lead to global spread of a virulent virus, a biosafety incident on a scale never before seen.”

Gain of function research was briefly paused because of these concerns, although critics debate as to when it restarted. For more than a decade, scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology have been discovering coronaviruses in bats in southern China and bringing them back to their lab for gain of function research, to learn how to deal with such a deadly virus should it arise in nature.

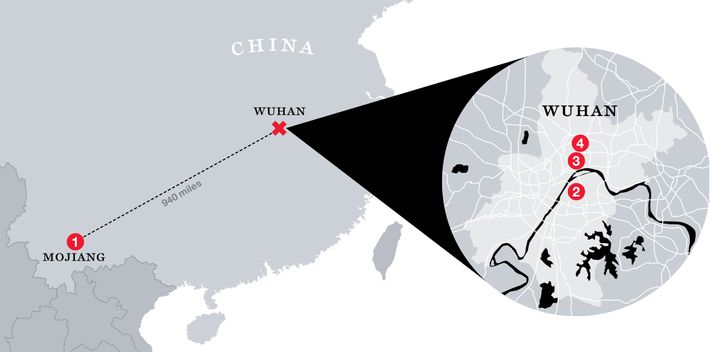

The closest known relative of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was found in a region of China almost 1000 miles from the Wuhan Institute of Virology—yet the pandemic apparently started in Wuhan. Biosafety experts have noted that lab leaks are common but rarely reported, as hundreds of lab accidents had happened in the US alone. 27

Two major events are probably responsible for the media’s change in tune. First, Trump was no longer president. Because Trump had said that the virus could have come from a Wuhan lab, Daszak and others used him as a convenient foil to attack their critics. But the framing of the lab leak hypothesis as a partisan issue was harder to sustain after Trump left the White House.

Second, after months of negotiation the Chinese government finally allowed the World Health Organization to come to Wuhan and investigate the pandemic’s origin. But in January 2021 WHO, which included Daszak on the team, returned with no evidence that the virus had arisen through natural spill-over. 18 More worryingly, members were allowed only a few hours of supervised access to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

The White House then released a statement making clear that it did not trust China’s propaganda denying that the virus could have come from one of the country’s labs. “We have deep concerns about the way in which the early findings of the covid-19 investigation were communicated and questions about the process used to reach them,” said the statement. “It is imperative that this report be independent, with expert findings free from intervention or alteration by the Chinese government.”

The following month the Washington Post editorial board called for an open and transparent investigation of the virus’s origins, highlighting Shi’s experiments with bat coronaviruses that were genetically very similar to the one that caused the pandemic. 19 It asked, “Could a worker have gotten infected or inadvertent leakage have touched off the outbreak in Wuhan?” The Wall Street Journal , citing a US intelligence document, recently reported that three Wuhan Institute of Virology researchers were admitted to hospital in November 2019. 20

To follow any US financial ties and to better understand how the pandemic started, Republicans have launched investigations of government agencies that fund coronavirus research, and one investigative committee has sent a letter to Daszak at EcoHealth Alliance demanding that he turn over documents. Meanwhile, Senate Republicans and Democrats have started to discuss an independent investigation of the virus’s origins.

A hard truth to swallow

The growing tendency to treat the lab leak scenario as worthy of serious investigation has put some reporters on the defensive. After Robert Redfield, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, appeared on CNN in March, Scientific American ’s editor in chief, Laura Helmuth, tweeted, “On CNN, former CDC director Robert Redfield shared the conspiracy theory that the virus came from the Wuhan lab.” The following day, Scientific American ran an essay calling the lab leak theory “evidence free.” And a week later a Nature reporter, Amy Maxmen, labelled the idea that the virus could have leaked from a lab as “conjecture.”

Helmuth did not respond to questions from The BMJ .

Some media outlets have attempted to justify their past reporting about the lab leak hypothesis as simply a matter of tracking a “scientific consensus” which, they say, has now changed. Vox posted an erratum noting, “Since this piece was originally published in March 2020, scientific consensus has shifted.”

The “scientific consensus” argument does not sit well with David Relman, a microbiologist at Stanford University, California. “We can’t even begin to talk about a consensus other than a consensus that we don’t know [the origins of SARS-CoV-2],” he recently told the Washington Post . 21

A year lost

While the narrative took months to change in the media, several high profile intelligence sources had treated the lab leak theory seriously from early on. In April 2020, Avril Haines joined two other former deputy directors of the Central Intelligence Agency to write an essay in Foreign Policy asking, “To what extent did the Chinese government misrepresent the scope and scale of the epidemic?” 22 A week later, one of the former intelligence officials who wrote that essay gave similar quotes to Politico .

Ignoring these early warnings led to a year of biased, failed reporting, says Wade. “They didn’t question what their sources were saying,” he says of the reporters who helped to sell the conspiracy theory narrative to the public. “That is the simple explanation for this phenomenon.”

An impartial, credible investigation?

As the news media scramble to correct and reflect on what went wrong with nearly a year of reporting, the episode has also highlighted quality control issues at the ubiquitous “fact checking” services.

Prominent outlets such as PolitiFact 23 and FactCheck.org 24 have added editor’s notes to pieces that previously “debunked” the idea that the virus was created in a lab or could have been bioengineered—softening their position to one of an open question that is “in dispute.” For almost a year Facebook sought to control misinformation by banning stories suggesting that the coronavirus was man made. After renewed interest in the virus’s origin, Facebook lifted the ban. 25

Whether a credible investigation will be made into the lab leak scenario remains to be seen. WHO and the Lancet both launched investigations last year ( box 2 ), but Daszak was involved in both, and neither has made significant progress.

September Weeks before the pandemic erupts, Jeremy Farrar (Wellcome Trust) and Anthony Fauci (US National Institutes of Health; NIH) help oversee a World Health Organization report highlighting an “increasing risk of global pandemic from a pathogen escaping after being engineered in a lab”

November Three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology are admitted to hospital, says a previously undisclosed US intelligence document reported by the Wall Street Journal on 23 May 2021

31 December WHO is notified of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan City

1 February Jeremy Farrar holds a teleconference with Anthony Fauci and others to discuss the outbreak’s origins

6 February A commentary from Chinese researchers based in Wuhan, arguing that “the killer coronavirus probably originated from a laboratory in Wuhan,” is posted and later removed from ResearchGate (the user account “Botao Xiao” is also deleted)

19 February An open letter is published in the Lancet from 27 scientists including Peter Daszak and Jeremy Farrar, who “strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that covid-19 does not have a natural origin”

19 February Science magazine reports: “Scientists ‘strongly condemn’ rumors and conspiracy theories about origin of coronavirus outbreak,” quoting Daszak as saying, “We’re in the midst of the social media misinformation age, and these rumors and conspiracy theories have real consequences, including threats of violence that have occurred to our colleagues in China.”

22 February New York Post publishes an article by a China scholar arguing that “coronavirus may have leaked from a lab”—subsequently censored by Facebook

6 March Kristian Andersen (Scripps Research Institute) thanks Jeremy Farrar (Wellcome), Anthony Fauci (NIH), and Francis Collins (NIH) “for your advice and leadership as we have been working through the SARS-CoV-2 ‘origins’ paper.” The paper is published on 17 March in Nature Medicine and states, “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.”

24 April NIH abruptly cuts funding to EcoHealth Alliance, allegedly on President Trump’s order

28 April Three former US intelligence agents write in Foreign Policy asking whether the virus emerged from nature or escaped from a Chinese lab

21 May New York Times depicts the Wuhan Institute of Virology as a victim of “conspiracy theories”

27 May Nature reports the lab leak hypothesis as “coronavirus misinformation” and “false information”

8 June The science magazine Undark reports that the lab leak is a conspiracy theory “that’s been broadly discredited”

30 December Associated Press investigation finds documents from March 2020 showing how Beijing has shaped and censored research into the origins of SARS-CoV-2

February Facebook places warning on an article by Ian Birrell about the origins of covid-19. Facebook says that these warnings reduce article viewership by 95%

13 February Jake Sullivan, US national security adviser, expresses “deep concerns” about WHO’s covid-19 investigation, calling on China to be more transparent

March Washington Post calls for serious investigations of the lab leak hypothesis

30 March WHO releases a report on its investigation into the origins of covid-19, listing the lab leak as least likely of the possible scenarios considered. Hours earlier, WHO’s director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, acknowledged that the lab leak hypothesis should “remain on the table” and called for a more extensive probe

30 March The US, Australian, Japanese, Canadian, UK, and other governments express concern over WHO’s investigation and call for “transparent and independent analysis and evaluation, free from interference and undue influence”

26 May Facebook lifts its ban on posts referencing the lab leak hypothesis

In recent weeks, several high profile scientists who once denigrated the idea that the virus could have come from a lab have made small steps into demanding an open investigation of the pandemic’s origin.

The NIH’s director, Francis Collins, said in a recent interview, “The Chinese government should be on notice that we have to have answers to questions that have not been answered about those people who got sick in November who worked in the lab and about those lab notebooks that have not been examined.” He added, “If they really want to be exonerated from this claim of culpability, then they have got to be transparent.” 26

But the nature of this investigation has still not been decided.

Competing interests: I am paid by various media outlets for journalism stories and consult part time for a non-profit institute focused on brain disorders. I run a newsletter called the Disinformation Chronicle .

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, not externally peer reviewed.

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ's website terms and conditions for the duration of the covid-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.

- ↵ USA Spending. Project Grant FAIN R01AI110964. https://www.usaspending.gov/award/ASST_NON_R01AI110964_7529

- Calisher C ,

- Carroll D ,

- Colwell R ,

- ↵ O’Neal A. A scientist who said no to covid groupthink. Wall Street J 2021 Jun 11. https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-scientist-who-said-no-to-covid-groupthink-11623430659

- ↵ Farrar J. Twitter. 9 Jun 2020. https://twitter.com/JeremyFarrar/status/1270354946295246848

- ↵ Daszak P. Email. 6 Feb 2020. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/The_Lancet_Emails_Daszak-2.6.20.pdf

- ↵ Baric R. Email. 6 Feb 2020. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Baric_Daszak_email.pdf

- ↵ Gorman J. Some scientists question W.H.O. inquiry into the coronavirus pandemic’s origins. New York Times 2021 Mar 4. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/04/health/covid-virus-origins.html

- ↵ Calls for further inquiries into coronavirus origins. New York Times 2021 Apr 7. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/04/07/science/virus-inquiries-pandemic-origins.html?referringSource=articleShare

- doi:10.1126/science.abj0016

- ↵ Addendum: competing interests and the origins of SARS-CoV-2 . Lancet 2021 ; 397 : 2449 - 50 . https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)01377-5/fulltext doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01377-5 . OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Lancet Covid-19 Commission. Origins, early spread of the pandemic, and one health solutions to future pandemic threats. https://covid19commission.org/origins-of-the-pandemic

- Subbaraman N

- ↵ Qiu J. How China’s “Bat Woman” hunted down viruses from SARS to the new coronavirus. Scientific American 2020 Jun 1. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-chinas-bat-woman-hunted-down-viruses-from-sars-to-the-new-coronavirus1/

- ↵ Nobel laureates and science groups demand NIH review decision to kill coronavirus grant. Science 2020 May 21. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/preposterous-77-nobel-laureates-blast-nih-decision-cancel-coronavirus-grant-demand

- Menachery VD ,

- Yount BL Jr . ,

- Debbink K ,

- ↵ A top virologist in China, at center of a pandemic storm, speaks out. New York Times 2021 Jun 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/14/world/asia/china-covid-wuhan-lab-leak.html

- ↵ World Health Organization. Mission summary: WHO field visit to Wuhan, China 20-21 January 2020. 22 Jan 2020. https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/22-01-2020-field-visit-wuhan-china-jan-2020

- ↵ Opinion: The WHO needs to start over in investigating the origins of the coronavirus. Washington Post 2021 Mar 6. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/the-who-needs-to-start-over-in-investigating-the-origins-of-the-coronavirus/2021/03/05/6f3d5a0e-7de9-11eb-a976-c028a4215c78_story.html

- ↵ Gordon MR, Strobel WP, Hinshaw D. Intelligence on sick staff at Wuhan lab fuels debate on covid-19 origin. Wall Street J 2021 May 23. https://www.wsj.com/articles/intelligence-on-sick-staff-at-wuhan-lab-fuels-debate-on-covid-19-origin-11621796228

- ↵ Dou E, Kuo L. A scientist adventurer and China’s “Bat Woman” are under scrutiny as coronavirus lab-leak theory gets another look. Washington Post 2021 Jun 3. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/coronavirus-bats-china-wuhan/2021/06/02/772ef984-beb2-11eb-922a-c40c9774bc48_story.html

- ↵ Morell M, Haines A, Cohen DS. Trump’s politicization of US intelligence agencies could end in disaster. Foreign Policy 2020 Apr 28. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/28/trump-cia-intimidation-politicization-us-intelligence-agencies-could-end-in-disaster/

- ↵ Archived fact-check: Tucker Carlson guest airs debunked conspiracy theory that covid-19 was created in a lab. PolitiFact 2021 May 17. https://www.politifact.com/li-meng-yan-fact-check/

- ↵ Fichera A. Report resurrects baseless claim that coronavirus was bioengineered. FactCheck.org. 17 Sep 2020. https://www.factcheck.org/2020/09/report-resurrects-baseless-claim-that-coronavirus-was-bioengineered/

- ↵ Lima C. Facebook no longer treating “man-made” covid as a crackpot idea. Politico 2021 May 26. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/05/26/facebook-ban-covid-man-made-491053

- ↵ Trump administration’s hunt for pandemic “lab leak” went down many paths and came up with no smoking gun. Washington Post 2021 Jun 15. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/us-intelligence-wuhan-lab-coronavirus-origin/2021/06/15/2fc2425e-ca24-11eb-afd0-9726f7ec0ba6_story.html

- ↵ Young A. Could an accident have caused covid-19? Why the Wuhan lab-leak theory shouldn’t be dismissed. USA Today 2021 Mar 22. https://eu.usatoday.com/in-depth/opinion/2021/03/22/why-covid-lab-leak-theory-wuhan-shouldnt-dismissed-column/4765985001/

The COVID lab leak theory is dead. Here’s how we know the virus came from a Wuhan market

ARC Australian Laureate Fellow and Professor, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Edward C Holmes receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council. He has received consultancy fees from Pfizer Australia and has held honorary appointments (for which he has received no renumeration and performed no duties) at the China CDC in Beijing and the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center (Fudan University)

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

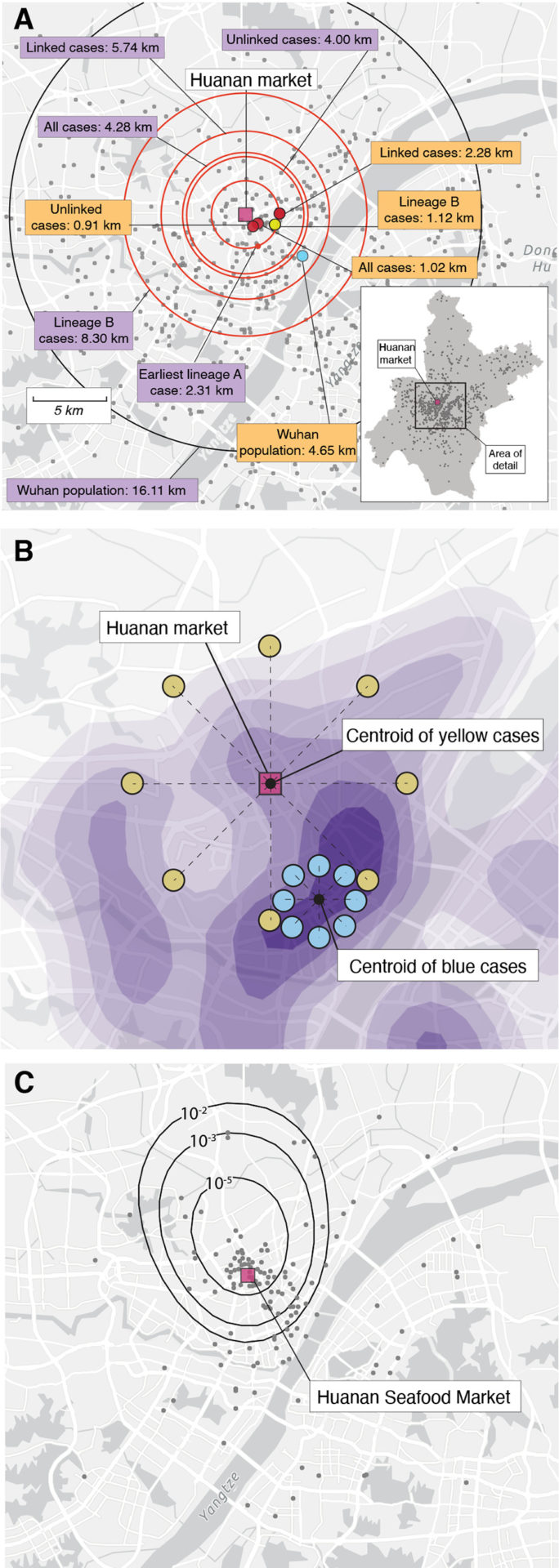

My colleagues and I published the most detailed studies of the earliest events in the COVID-19 pandemic last month in the journal Science.

Together, these papers paint a coherent evidence-based picture of what took place in the city of Wuhan during the latter part of 2019.

The take-home message is the COVID pandemic probably did begin where the first cases were detected – at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.

At the same time this lays to rest the idea that the virus escaped from a laboratory.

Huanan market was the pandemic epicentre

An analysis of the geographic locations of the earliest known COVID cases – dating to December 2019 – revealed a strong clustering around the Huanan market. This was true not only for people who worked at or visited the market, but also for those who had no links to it.

Although there will be many missing cases, there’s no evidence of widespread sampling bias: the first COVID cases were not identified simply because they were linked to the Huanan market.

The Huanan market was the pandemic epicentre. From its origin there, the SARS-CoV-2 virus rapidly spread to other locations in Wuhan in early 2020 and then to the rest of the world.

The Huanan market is an indoor space about the size of two soccer fields. The word “seafood” in its name leaves a misleading impression of its function. When I visited the market in 2014, a variety of live wildlife was for sale including raccoon dogs and muskrats.

At the time I suggested to my Chinese colleagues that we sample these market animals for viruses. Instead, they set up a virological surveillance study at the nearby Wuhan Central Hospital, which later cared for many of the earliest COVID patients.

Wildlife were also on sale in the Huanan market in 2019. After the Chinese authorities closed the market on January 1 2020, investigative teams swabbed surfaces, door handles, drains, frozen animals and so on.

Most of the samples that later tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were from the south-western corner of the market. The wildlife I saw for sale on my visit in 2014 were in the south-western corner.

This establishes a simple and plausible pathway for the virus to jump from animals to humans.

Read more: How do viruses mutate and jump species? And why are 'spillovers' becoming more common?

Animal spillover

SARS-CoV-2 has evolved into an array of lineages, some familiar to us as the “variants of concern” (what we call Delta, Omicron and so on). The first split in the SARS-CoV-2 family tree – between the “A” and “B” lineages – occurred very early in the pandemic. Both lineages have an epicentre at the market and both were detected there.

Further analyses suggest the A and B lineages were the products of separate jumps from animals. This simply means there was a pool of infected animals in the Huanan market, fuelling multiple exposure events.

Reconstructing the history of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence through time showed the B lineage was the first to jump to humans. It was followed, perhaps a few weeks later, by the A lineage.

All these events are estimated to have occurred no earlier than late October 2019. Claims that the virus was spreading before this date can be dismissed.

What’s missing, of course, is that we don’t yet know exactly which animals were involved in the transfer of SARS-CoV-2 to humans. Live wildlife were removed from the Huanan market before the investigative team entered, increasing public safety but hampering origin hunting.

The opportunity to find the direct animal host has probably passed. As the virus likely rapidly spread through its animal reservoir, it’s overly optimistic to think it would still be circulating in these animals today.

The absence of a definitive animal source has been taken as tacit support for counter claims that SARS-CoV-2 in fact “leaked” from a scientific laboratory – the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Death knell for the lab leak theory

The lab leak theory rests on an unfortunate coincidence: that SARS-CoV-2 emerged in a city with a laboratory that works on bat coronaviruses.

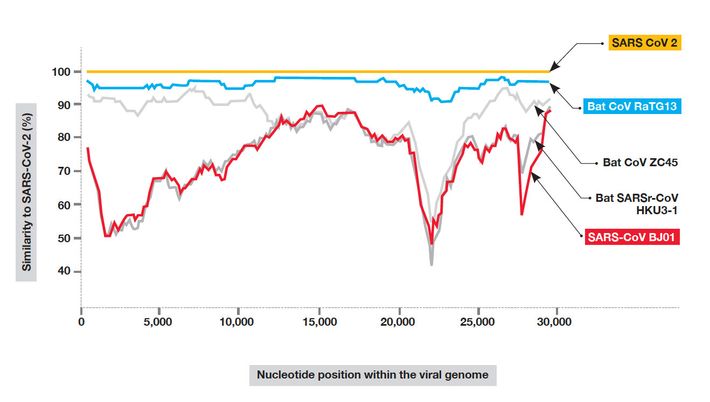

Some of these bat coronaviruses are closely related to SARS-CoV-2. But not close enough to be direct ancestors.

Sadly, the focus on the Wuhan Institute of Virology has distracted us from a far more important connection: that, like SARS-CoV-1 (which emerged in late 2002) before it, there’s a direct link between a coronavirus outbreak and a live animal market.

Consider the odds that a virus that leaked from a lab was first detected at the very place where you would expect it to emerge if it in fact had a natural animal origin – vanishingly low. And these odds drop further as we need to link both the A and B lineages to the market.

Was the market just the location of a super-spreading event? Nothing says so. It wasn’t a crowded location in the bustling and globally connected metropolis of Wuhan. It’s not even close to being the busiest market or shopping mall in the city.

For the lab leak theory to be true, SARS-CoV-2 must have been present in the Wuhan Institute of Virology before the pandemic started. This would convince me.

But the inconvenient truth is there’s not a single piece of data suggesting this. There’s no evidence for a genome sequence or isolate of a precursor virus at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Not from gene sequence databases, scientific publications, annual reports, student theses, social media, or emails.

Even the intelligence community has found nothing. Nothing. And there was no reason to keep any work on a SARS-CoV-2 ancestor secret before the pandemic.

To assign the origin of SARS-CoV-2 to the Wuhan Institute of Virology requires a set of increasingly implausible “what if?” scenarios. These eventually lead to preposterous suggestions of clandestine bioweapon research.

The lab leak theory stands as an unfalsifiable allegation. If an investigation of the lab found no evidence of a leak, the scientists involved would simply be accused of hiding the relevant material. If not a conspiracy theory, it’s a theory requiring a conspiracy.

It provides a convenient vehicle for calls to limit, if not ban outright, gain-of-function research in which viruses with greatly different properties are created in labs. Whether or not SARS-CoV-2 originated in this manner is incidental.

Read more: We want to know where COVID came from. But it’s too soon to expect miracles

Wounds that may never be healed

The acrid stench of xenophobia lingers over much of this discussion. Fervent dismissals by the Chinese scientists of anything untoward are blithely cast as lies.

Yet during this crucial period these same scientists were going to international conferences and welcoming visitors. Do we honestly believe they would have such a pathological disdain for the consequences of their actions?

The debate over the origins of COVID has opened wounds that may never be healed. It has armed a distrust in science and fuelled divisive political opinion. Individual scientists have been assigned the sins of their governments.

The incessant blame game and finger pointing has reduced the chances of finding viral origins even further. History won’t judge this period kindly.

Global collaboration is the bedrock of effective pandemic prevention, but we’re in danger of destroying rather than building relationships. We may even be less prepared for a pandemic than in 2019. Despite political barriers and a salivating media, the evidence for a natural animal origin for SARS-CoV-2 has increased over the past two years. To deny it puts us all at risk.

- Coronavirus

- Wildlife trade

- Zoonotic viruses

- Wuhan lab theory

- Wuhan Institute of Virology

- Wuhan lab-leak hypothesis

- COVID-19 origin

- lab leak hypothesis

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Filed under:

- The lab leak hypothesis, explained

We may never know for sure if the virus that causes Covid-19 leaked from a lab. But that won’t stop the debate.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69417593/AP_21034209534777_copy.0.jpg)

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The lab leak hypothesis, explained

Where did the virus that causes Covid-19 come from?

It’s one of the most persistent mysteries of the pandemic. The debate about it among scientists, policymakers, journalists, amateur internet sleuths, and the general public has reignited with new revelations and new voices in the mix.

Most recently, emails obtained by the Washington Post and BuzzFeed showed that National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony Fauci was corresponding with a scientist as early as January 2020 investigating the possibility that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, may have been engineered in a lab. An article in Vanity Fair highlighted how efforts to probe a lab leak were suppressed within parts of the US government as some officials worried that a lab in Wuhan, China, that received US funding may have been the source.

Scientists last year argued that the most plausible explanation is the “natural emergence” of the SARS-CoV-2 virus: It jumped from bats, or an intermediary species, to humans in a random event sometime in 2019. Many still hold this view, and some have become even more confident in this pathway.

Several media outlets, including Vox, also downplayed in 2020 the possibility that human error launched the virus, after many scientists with relevant experience described the idea as extremely unlikely. In February 2020, 27 scientists co-signed a letter in The Lancet affirming their belief in a natural origin of the virus and decrying efforts to pin the blame for the outbreak on Chinese scientists.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22626074/Screen_Shot_2021_06_03_at_2.14.33_PM.png)

But in recent weeks, more scientists — including some who had not weighed in until now — have spoken up about the possibility that the virus may have escaped a laboratory in China, and argued that this scenario has not been adequately investigated.

The Covid-19 pandemic has illustrated that science is essential for grappling with the disease, but also that experts can get things wrong. For example, the World Health Organization in January 2020 said that there was “ no clear evidence ” of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 between people. The US surgeon general told Americans in February 2020 that face masks were not effective in slowing the spread of the disease. It could be possible, then, that the dismissal of a laboratory origin of the virus was premature among some experts amid the flurry of developments in the early stages of a global outbreak.

“We must take hypotheses about both natural and laboratory spillovers seriously until we have sufficient data,” reads a letter published in the journal Science in May 2021, co-authored by 18 researchers.

Some scientists had been reluctant to publicly broach the “lab leak” hypothesis in part because the Trump administration had asserted, without clear evidence, its confidence in the theory, as it tried to find ways to blame China for the pandemic and deflect scrutiny from the White House’s mishandling of the crisis. The idea also collapsed into conspiracy theories, like the notion that the virus was deliberately released as a bioweapon .

The lab leak hypothesis “really is not a fringe theory,” Marc Lipsitch , an epidemiology professor at the Harvard School of Public Health and a co-signer of the letter, told CNN . “It had been viewed as a fringe theory because it was espoused in fringe ways by some people with political agendas.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22638281/GettyImages_1230937740_copy.jpg)

Lipsitch and other researchers pushing for further investigation say that the Chinese government hasn’t been forthcoming with critical details about its research on coronaviruses; it also ordered some early lab specimens of the virus to be destroyed and censored reporting around the outbreak . The calls for more transparency from scientists prompted the Biden administration to order US intelligence agencies to investigate the possibility of an accidental lab leak. The answer to the question of how the virus originated has as much political import as it does scientific.

At the most basic level, the case for the natural origins of the virus rests on incomplete evidence, while the lab leak hypothesis rests on the gaps in that very evidence.

A natural exposure route for SARS-CoV-2 still seems far more likely to many scientists, but a satisfying answer one way or another may never coalesce as the initial infections recede into history and China continues to withhold data and records from those early days. Scientists still haven’t determined from which animal the virus hopped into humans, but neither have they found any trace of SARS-CoV-2 in a laboratory prior to its emergence. All the while, the tense US-China relationship looms over the investigation, threatening to throttle the search for answers.

Many prominent voices in science, politics, and national security are now deeply invested in seeing this investigation through. Here’s how some of the researchers currently engaged in the conversation are parsing the evidence, what they see as some of the most important lines of inquiry going forward, and what they say we may never know.

Why some scientists say that a lab origin deserves a closer look

The term “lab leak” refers to the possibility that the SARS-CoV-2 virus or a close relative was at some point being studied at a laboratory in China prior to the Covid-19 pandemic and then later escaped. In particular, investigation proponents are interested in the Wuhan Institute of Virology near the original epicenter of the Covid-19 outbreak. After the 2003 SARS outbreak , the facility increased its focus on emerging diseases, including respiratory infections caused by coronaviruses.

The possibility of a lab leak crossed the mind of Shi Zhengli , a renowned virologist at the Wuhan lab. She told Scientific American last year that she recalled being told in December 2019 about a mysterious pneumonia caused by a coronavirus spreading in the city of Wuhan and wondering if the pathogen came from her lab.

There have been reports that researchers at the institute were performing gain-of-function experiments , where a natural virus is modified to become more virulent or to better infect humans. This research tries to map potential ways a virus could mutate and lead to an outbreak, allowing scientists to get a head start on countering a potentially dangerous pathogen. But such research is dangerous and controversial. The National Institutes of Health declared a moratorium on funding gain-of-function research in 2014, lifting it in 2017 for experiments that undergo review by an expert panel.

US officials have been adamant that US funding did not support any gain-of-function research at the Wuhan Institute, or anywhere in the world. NIH Director Francis Collins said in a May statement that US federal health research agencies have never “approved any grant that would have supported ‘gain-of-function’ research on coronaviruses that would have increased their transmissibility or lethality for humans.”

Scientists at the Wuhan lab were known to be working with an international team on creating chimeric versions of different coronaviruses to study the potential of a human outbreak, though they say that these chimeric viruses did not increase in pathogenicity and therefore do not constitute gain of function. The chimeras in the experiment were also created in the US, not China. Wuhan Institute researchers also published a paper in 2017 reporting on a bat coronavirus that could be transmitted directly to humans, with researchers creating chimeras of the wild virus to see if they could infect human cells. That study had funding from the US National Institutes of Health.

Looking at these studies, there are scientists who say such experiments meet the definition. “The research was — unequivocally — gain-of-function research,” Richard Ebright , a microbiology researcher at Rutgers University, told the Washington Post .

There is also a possibility that other, more direct gain-of-function experiments were conducted with other funding sources, but no evidence has emerged for this.

That said, the lab leak hypothesis doesn’t hinge on risky gain-of-function research being conducted at the lab, explained Alina Chan, a researcher at the Broad Institute and a co-signer of the Science letter.

“Maybe a few people think that there could’ve been some gain-of-function research, but I’d say that a lot of scientists who are asking for an investigation say that this was a lab accident of a mostly natural, or completely natural, virus,” Chan said.

She and other scientists want to investigate the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 or a very closely related virus escaped during normal laboratory operations. The two strongest possibilities, according to Chan, are, one, that a researcher at the Wuhan Institute of Virology was exposed to a bat coronavirus while collecting samples in the field and inadvertently brought the infection back to Wuhan. The field, in this case, is the native habitat of the bats in the southeastern provinces of China, more than 1,000 miles from Wuhan. And two, scientists at the lab could have been exposed to a sample of SARS-CoV-2 that was under study and then spread the virus to others.

Indeed, dangerous pathogens have leaked out of laboratories several times before, and human error is a constant risk in any research institution. “The only labs that don’t have accidents are labs that are not functional,” Chan said.

She pointed out that someone unwittingly falling sick with a virus under study in a lab has happened before in China. In 2004, a researcher contracted SARS after a stint working at the Chinese National Institute of Virology in Beijing. The researcher went on to infect her mother and a nurse at the hospital who went on to infect others, leading to 1,000 placed under quarantine or medical supervision.

Another concern was that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was handling coronavirus samples at biosafety level 2 precautions when most other labs recommend a biosafety level of 3 or higher. At biosafety level 2, lab access is restricted, researchers must wear personal protective equipment like gloves, lab coats, and eye protection, and much of the experimental work is conducted in biosafety cabinets that filter air rather than open lab benches.

Biosafety level 3 includes all the precautions of lower levels and adds medical surveillance for lab workers, the use of respirator masks, and lab access controlled with two sets of self-closing and locking doors. The biosafety level 3 measures are aimed at controlling potentially lethal respiratory pathogens that spread through the air, while biosafety level 2 is meant for pathogens that pose a “moderate hazard.”

So seeing that the Wuhan lab was handling viruses that can travel through the air at a safety level not designed for it alarmed some observers. “When scientists hear about this, they get really freaked out,” Chan said.

W. Ian Lipkin , a virologist at Columbia University, co-authored a Nature Medicine paper in March 2020 that reported the most likely origin of the virus in humans was a natural spillover from animals. But he told the journalist Donald McNeil in May 2021 that he was alarmed when he learned that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was conducting research on similar viruses at a lower level of protection.

“People should not be looking at bat viruses in BSL-2 labs,” Lipkin said. “My view has changed.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22638293/GettyImages_643959858_copy.jpg)

Chan also noted that the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was initially suspected as the location where a SARS-CoV-2 spillover from animals to humans occurred, but to date, no infected animal has been identified and Chinese researchers have ruled it out as the origin of the virus. The initial outbreak could have occurred because so many people were in close proximity at the bustling market, but the virus may have made the leap to humans elsewhere.

There are also allegations that the Chinese government hasn’t been forthright about the early days of the pandemic and has withheld critical information from investigators, making it hard to eliminate a lab leak as a possibility. “I can also be convinced of a natural origin if that is properly investigated too,” Chan said in an email. “The problem is that the most definitive pieces of evidence would be inside of China where we currently have no access.”

A team from the World Health Organization that visited China in January and February of this year reported that they had difficulty getting all the information they wanted about the origins of SARS-CoV-2.

“In my discussions with the team, they expressed the difficulties they encountered in accessing raw data,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a briefing in March . “I expect future collaborative studies to include more timely and comprehensive data sharing.”

Properly investigating the possibility of a laboratory leak, if only to rule it out, would help answer critical scientific questions while also bolstering public confidence in the process, proponents argue. “We have to show that we have the will to investigate whenever something like this happens and that we have a system in place,” Chan said.

Why the lab leak theory is getting so much attention now

Questions about whether SARS-CoV-2 may have escaped from a lab have been simmering since the beginning of the pandemic, but several recent developments catapulted the debate back into the news, and even into Congress .

At the beginning of the year, New York Magazine (which is owned by Vox Media) published a long article by the novelist Nicholson Baker making the case that the virus may have leaked from a lab in China. Journalist Nicholas Wade made a similar case in an article published on Medium in May. The letter published by Science in May, which called for a more thorough investigation into the hypothesis, was another driver of the conversation. A few days after the letter, an article in the Wall Street Journal resurfaced US intelligence reports about three researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology who sought medical care for influenza-like symptoms in November 2019. That’s earlier than the first confirmed case of Covid-19 , which occurred on December 8, 2019, according to Chinese officials. (There’s no evidence that the researchers had Covid-19, however.)

Shortly thereafter, the Wall Street Journal highlighted the case of six miners in China who fell ill in 2012 after being hired to clear a cave of bat guano. The Wuhan Institute of Virology was called in to investigate. Researchers from the lab tested bats from the mine for coronaviruses and found an unidentified strain resembling SARS; several bats were infected with more than one virus. That created opportunities for recombination, in which viruses undergo rapid, large-scale mutations that create new pathogens.

One of the unidentified viruses, called RaTG13, was later found to have 96.2 percent genetic overlap with SARS-CoV-2, hinting that it may have been a predecessor. A WHO team reported that the lab wasn’t able to culture the virus, and was only in possession of its genetic sequence. If these reports are to be believed, that means the institute didn’t have an infectious ancestor to SARS-CoV-2 in its custody.

In the wake of these media reports and rising public interest, President Biden ordered US intelligence agencies last month to increase their efforts in investigating the potential of a laboratory origin of SARS-CoV-2 and report back in 90 days.

For some scientists, the resurgent interest in a lab leak has been frustrating, rather than illuminating. “Quite frankly, over the last number of days, we’ve seen more and more and more discourse in the media with terribly little actual news, evidence, or new material,” said Michael Ryan , executive director of the World Health Organization’s health emergencies program, during a May 28 press conference.

But for others, it has been validating. Former US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield told Vanity Fair that he received death threats last year after stating publicly that he thought the virus originated in a lab.

And for still other researchers, the issue remains too contentious to discuss publicly. One scientist contacted for this article declined to comment on the record in part out of fear of harassment. Nonetheless, this renewed attention seems unlikely to go away anytime soon.

Why other scientists remain skeptical of the lab leak hypothesis

Despite the concerns and unknowns around the activities at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, there is no evidence SARS-CoV-2 ever passed through the laboratory; rather, the circumstances only indicate that a lab leak was possible.

Some scientists in the US were already looking into this possibility in the early days of the pandemic. Kristian Andersen, a professor at the Scripps Research Institute, exchanged emails with Fauci in January 2020 about his suspicions that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was engineered because its genetics didn’t resemble what he thought would occur in nature, according to documents obtained by BuzzFeed and the Washington Post. “I should mention that after discussions earlier today, Eddie, Bob, Mike, and myself all find the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory,” Andersen wrote to Fauci.

Andersen then investigated the possibility, and co-authored the March 2020 Nature Medicine paper on the origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus with Lipkin that reported the most likely origin of the virus was a spillover from an animal. Unlike Lipkin, Andersen has only become more convinced the virus came into humans via a natural exposure route.

“We cannot categorically say that SARS-CoV-2 has a natural origin but, based on available scientific data, the most likely scenario by far is that SARS-CoV-2 came from nature,” Andersen told Vox in an email. “No credible evidence has been presented to support the hypothesis that the virus was engineered in, or leaked from, a lab — such statements are based on pure speculation.”

Then what would it take to demonstrate that the virus escaped a lab?

“Evidence that [the Wuhan Institute of Virology] or another Wuhan virology lab had SARS-CoV-2 or something 99% similar would be the smoking gun,” Robert Garry , a virologist at Tulane University and another co-author of the Nature Medicine paper, said in an email. “There is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 or an immediate progenitor virus existed in any laboratory before the pandemic.”

He, too, has become more convinced that the virus jumped to humans somewhere outside the lab. “The only change since we wrote our manuscript on the Proximal Origins of SARS-CoV-2 is that I now consider any of the lab leak hypotheses to be extremely unlikely,” he said.

Shi Zhengli at the Wuhan Institute of Virology told Scientific American she instructed her team to sequence the genomes of all the viruses they were studying in their laboratory and compare them to sequences obtained from Covid-19 patients. None matched. “That really took a load off my mind,” she said. (Shi did not respond to a Vox request for comment.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22638318/GettyImages_643961442_copy.jpg)

Several other factors point toward a natural origin of SARS-CoV-2, according to Vincent Racaniello , a virologist at Columbia University. Among them is that the 2003 SARS virus outbreak established a precedent for a coronavirus jumping from bats to an intermediary species to humans. In that case, the intermediary — civet cats — was identified; scientists have been warning for years that a similar scenario could easily occur again.

Further animal investigations showed that there are a number of viruses like SARS-CoV-2 in bats, not just in China but also in Thailand, Cambodia, and Japan. These viruses are not direct ancestors of SARS-CoV-2, but they are closely related. Viruses mutate all the time, and the more widespread they are, the more changes can occur. Seeing a related virus over such a wide area shows there was ample opportunity for it to spread and mutate in nature before it made the final jump into humans.

The WHO also found that in the earliest days of the pandemic, during the outbreak in Wuhan, China, in 2019, there were two distinct lineages of the virus with different transmission patterns through the region. “That tells us that there were either two wildlife sources or that, early on, the virus switched from one animal to another,” Racaniello said. “That’s very difficult to make sense of with a lab origin. In my opinion, that’s really strong evidence this came from nature, because it’s a simpler scenario.”

He also pointed out that while there have been leaks of pathogens from laboratories in the past, those were known diseases at the time: “There has never been a new virus to come out of a lab.”

As for the circumstances that hint at a lab leak, some scientists still don’t find them compelling. For instance, while the Wuhan Institute of Virology was handling coronaviruses at biosafety level 2, none of the viruses the lab was known to be studying have leaked, and, again, there is no evidence the lab had any contact with SARS-CoV-2.

“It’s not actually news that the Wuhan Institute was handling these viruses at BSL-2. It’s in the methods of their papers going back years,” said Stephen Goldstein , a virologist at the University of Utah. “I don’t see how people can hold that up as a specific piece of evidence for any given scenario.”

Similarly, investigators say they were aware for months of reports that scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology sought treatment for an unknown illness. Virologist Marion Koopmans , a member of the WHO investigation team that visited China earlier this year, told NBC News they investigated and had already ruled out those infections as early cases of Covid-19. “There were occasional illnesses because that’s normal,” she said. “There was nothing that stood out.”

China’s reluctance to cooperate with outside investigators and share information could be a sign of a cover-up of a lab leak. But it could also stem from reasons that have nothing to do with the virus, perhaps a consequence of broader international tensions.

And while the WHO’s initial investigation was not comprehensive, researchers are in the planning stages of another trip to China to study the origins of the virus. This time, the team wants to look at blood samples going back two years and screen them for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. That could allow scientists to map previously unknown chains of transmission of the virus and narrow the scope of possible origins.

We can take steps to stop a future pandemic without knowing where this one came from

If SARS-CoV-2 did escape via a laboratory accident, it’s urgent to try to figure out exactly how it happened and to take precautions, especially given that there are other laboratories conducting research on dangerous pathogens around the world. “If the lab-leak hypothesis is put aside because it is too contentious, laboratory safety and especially risky research will continue to be ignored,” David Relman , an infectious disease researcher at Stanford University and a co-signer of the Science letter, wrote Wednesday in the Washington Post . “We cannot afford to bury our heads in the sand about one possible cause of the origins of Covid-19 simply because it is politically sensitive.”

On the other hand, there is no reason why laboratories would need to wait on the outcome of such an investigation to take steps to prevent future accidents. They could conduct safety audits and ensure experiments are conducted under the proper biosafety levels. Over the long term, facilities researching viruses like the one in Wuhan could even be relocated away from major population centers.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22638323/AP_21034253952164_copy.jpg)

Similarly, policymakers could take steps to prevent natural spillovers. As humans venture further into wilderness areas to cultivate land and resources, the chances grow of a previously unknown virus crossing over from animals into people. The wildlife trade and venues like wet markets certainly aren’t helping. In a sense, even a “natural origin” of SARS-CoV-2 stems from human causes. “All these spillovers, wherever they are, it’s because human activity is encroaching upon animal activity,” Racaniello said.

While it would be ideal to investigate all possible origins of a deadly global disease, it may not be practical. Given that one pathway has evidence for it and another does not, some scientists say it’s better to focus on the likelier routes.

“It is a mistake to weight these possibilities equally, and it risks underresourcing the investigations into animal sources of this virus that we really need so we can understand the pathways of emergence and cut them off before this happens again,” Goldstein said.

Tracing the animal origins of SARS-CoV-2 is already poised to be a monumental and tedious task for scientists. It will require immense resources as well as cooperation with authorities in China, which may be jeopardized if an investigation into a lab leak isn’t handled with tact.

“Sure ‘investigate’ the lab. But, arm-waving about an often mentioned ‘forensic’ investigation (whatever that means) is not helpful,” Garry said in an email.

More answers about the roots of the pandemic may emerge in the coming months, but it’s likely that further inquiries won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. Even after the pandemic fades away, the virus that caused it may long frustrate and confound.

Will you support Vox today?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

In This Stream

Coronavirus pandemic: news and updates on new cases and its spread.

- The FBI and Energy Department think Covid-19 came from a lab. Now what?

- We shouldn’t go back to “normal.” Normal wasn’t good enough.

Biden’s surprise proposal to debate Trump early, explained

Make “free speech” a progressive rallying cry again, the silver lining in a very bad poll for biden, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

What you need to know about the COVID-19 lab-leak hypothesis

Newly reported information has revived scrutiny of this possible origin for the coronavirus, which experts still call unlikely though worth investigating.

Months after a World Health Organization investigation deemed it “extremely unlikely” that the novel coronavirus escaped accidentally from a laboratory in Wuhan, China, the idea is back in the news, giving new momentum to a hypothesis that many scientists believe is unlikely, and some have dismissed as a conspiracy theory .

The renewed attention comes on the heels of President Joe Biden’s ordering U.S. intelligence agencies on May 26 to “ redouble their efforts ” to investigate the origins of the coronavirus. On May 11, Biden’s chief medical adviser, Anthony Fauci, acknowledged he’s now “ not convinced ” the virus developed naturally—an apparent pivot from what he told National Geographic in an interview last year.

Also last month, more than a dozen scientists—top epidemiologists, immunologists, and biologists—wrote a letter published in the journal Science calling for a thorough investigation into two viable origin stories: natural spillover from animal to human, or an accident in which a wild laboratory sample containing SARS-CoV-2 was accidentally released. They urged that both hypotheses “be taken seriously until we have sufficient data,” writing that a proper investigation would be “transparent, objective, data-driven, inclusive of broad expertise, subject to independent oversight,” with conflicts of interest minimized, if possible.

“Anytime there is an infectious disease outbreak it is important to investigate its origin,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease physician and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security who did not contribute to the letter in Science . “The lab-leak hypothesis is possible—as is an animal spillover,” he says, “and I think that a thorough, independent investigation of its origins should be conducted.”

Unanswered questions

The origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 and has infected more than 171 million people, killing close to 3.7 million worldwide as of June 4, remain unclear. Many scientists, including those that participated in the WHO’s months-long investigation, believe the most likely explanation is that that it jumped from an animal to a person—potentially from a bat directly to a human, or through an intermediate host. Animal-to-human transmission is a common route for many viruses; at least two other coronaviruses, SARS and MERS , were spread through such zoonotic spillover.

Other scientists insist it’s worth investigating whether SARS-CoV-2 escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a laboratory that has studied coronaviruses in bats for more than a decade.

For Hungry Minds

The WHO investigation —a joint effort between WHO-appointed scientists and Chinese officials—concluded it was “extremely unlikely” the highly transmissible virus escaped from a laboratory. But the WHO team suffered roadblocks that led some to question its conclusions; the scientists were not permitted to conduct an independent investigation and were denied access to any raw data. ( We still don’t know the origins of the coronavirus. Here are 4 scenarios .)

On March 30, when the WHO released its report, its director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, called for further studies . “All hypotheses remain on the table,” he said at the time.

Then on May 11, Fauci told PolitiFact that while the virus most likely emerged via animal-to-human transmission, “it could have been something else, and we need to find that out.”

Recently disclosed evidence, first reported by the Wall Street Journal , has added fuel to the fire: Three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology fell sick in November 2019 and sought hospital care, according to a U.S. intelligence report. In the final days of the Trump administration, the State Department released a statement that researchers at the institute had become ill with “symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illness.”

You May Also Like

What is white lung syndrome? Here's what to know about pneumonia

COVID-19 is more widespread in animals than we thought

A deer may have passed COVID-19 to a person, study suggests

Most epidemiologists and virologists who have studied the novel coronavirus believe that it began spreading in November 2019. China says the first confirmed case was on December 8, 2019. During a briefing in Beijing this week, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, accused the U.S. of “ hyping up the theory of a lab leak ,” and asked, “does it really care about the study of origin tracing, or is it trying to divert attention?” Zhao also denied the Wall Street Journal report that three people had gotten sick.

Lab leak still ‘unlikely’

Some conservative politicians and commentators have embraced the lab-leak theory, while liberals more readily rejected it, especially early in the pandemic. The speculation has also heightened ongoing tensions between the U.S. and China.

On May 26, as the U.S. Senate passed a bill to declassify intelligence related to potential links between the Wuhan laboratory and COVID-19, Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, a Republican who sponsored the bill, said, “the world needs to know if this pandemic was the product of negligence at the Wuhan lab,” and lamented that “for over a year, anyone asking questions about the Wuhan Institute of Virology has been branded as a conspiracy theorist.”

Peter Navarro, Donald Trump’s former trade adviser, asserted in April 2020 that SARS-CoV-2 could have been engineered as a bioweapon, without citing any evidence.

The theory that SARS-CoV-2 was created as a bioweapon is “completely unlikely,” says William Schaffner, a professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. For one thing, he explains, for a bioweapon to be successful, it must target an adversarial population without affecting one’s own. In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 “cannot be controlled,” he says. “It will spread, including back on your own population,” making it an extremely “counterproductive biowarfare agent.”

The more plausible lab-leak hypothesis, scientists say, is that the Wuhan laboratory isolated the novel coronavirus from an animal and was studying it when it accidentally escaped. “Not knowing the extent of its virulence and transmissibility, a lack of protective measures [could have] resulted in laboratory workers becoming infected,” initiating the transmission chain that ultimately resulted in the pandemic, says Rossi Hassad, an epidemiologist at Mercy College.

But Hassad adds he believes that this lab-leak theory is on the “extreme low end” of possibilities, and it “will quite likely remain only theoretical following any proper scientific investigation,” he says.

Biden ordered U.S. intelligence agencies to report back with their findings in 90 days, which would be August 26.

Based on the available information, Eyal Oren, an epidemiologist at San Diego State University, says it’s apparent why the most accepted hypothesis is that this virus originated in an animal and jumped to a human: “What is clear is that the genetic sequence of the COVID-19 virus is similar to other coronaviruses found in bats,” he says.

Some scientists remain skeptical that concrete conclusions can be drawn. “At the end, I anticipate that the question” of SARS-CoV-2’s origins “will remain unresolved,” Schaffner says.

In the meantime, science “moves much more slowly than the media and news cycles,” Oren says.

Related Topics

- CORONAVIRUS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- WILDLIFE WATCHING

5 things to know about COVID-19 tests in the age of Omicron

Seeking the Source of Ebola

Here's what we know about the BA.2 Omicron subvariant driving a new COVID-19 wave

Humans are creating hot spots where bats could transmit zoonotic diseases

Hippos, hyenas, and other animals are contracting COVID-19

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Science-Based Medicine

Exploring issues and controversies in the relationship between science and medicine

The rise and fall of the lab leak hypothesis for the origin of SARS-CoV-2

Two new studies were published last week that strongly support a natural zoonotic origin for COVID-19 centered at the wet market in Wuhan, China. Naturally, lab leak proponents soberly considered this new evidence and thought about changing their minds. Just kidding! They doubled down on the conspiracy mongering, because of course they did.

Ever since the coronavirus now known as SARS-CoV-2 was first identified as the cause of an outbreak of a mysterious severe viral pneumonia in Wuhan, China two and a half years ago, a disease that later spread to the rest of the world as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been intense curiosity about the origins of the virus. The most plausible hypothesis was that, like many diseases before, SARS-CoV-2 had a zoonotic origin; i.e., it developed the ability to “jump” from an animal reservoir to humans. Far less plausible, albeit not impossible, was the hypothesis that the novel coronavirus was created in a laboratory and then escaped, either through incompetence or malfeasance, a hypothesis that became more colloquially known as the “lab leak” hypothesis. Last week, two papers were finally published in Science that, under normal circumstances, would be, if not the final nails in the coffin of the lab leak hypothesis, getting very close. One examined the molecular epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 and the other demonstrated that the wet market in Wuhan was indeed an early epicenter of the pandemic . Steve Novella has already discussed the studies , but that’s never stopped me before, given that having a few days to look at them allowed me also to judge reactions. Let’s just say that, contrary to the assertions of some optimists, these studies haven’t made much of an impact on conspiracy theorists, other than to provide them with targets to try to discredit.

Before I get to the studies, though, let’s look at some background on the lab leak hypothesis and conspiracy theories. I do this for two reasons. First, I want to show what these studies add to what we know about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. Second, it’s been a long time since I’ve written about this issue, and I think a recap is overdue.

A brief history of the lab leak hypothesis/conspiracy theory

Since the early days of the pandemic, there has been a question of whether SARS-CoV-2 arose naturally or had escaped from a lab. The latter hypothesis didn’t start out as a conspiracy theory, as lab leaks have happened before—although none had ever caused a pandemic that caused millions of deaths worldwide, over a million in the US alone. However, it rapidly took on the characteristics of a conspiracy theory such that even those advocating the “lab leak” hypothesis often had difficulty not interspersing more serious scientific arguments with what can be only described as a dollop of conspiratorial thinking. As time went on, if anything, the lab leak hypothesis drifted further and further from legitimate science and deeper and deeper into conspiracyland, such that, try as I might, I now have a difficult time finding examples of lab leak advocates who don’t add conspiracy mongering narratives to their arguments.

Here’s what I mean. By by May 2021 it clearly had developed all the hallmarks of a conspiracy theory, complete with a coverup narrative in which China and powerful forces in the US were “suppressing” all mention of a lab leak as a “conspiracy theory”, attacks on funding sources of investigators doing research on coronaviruses, bad science in the form of anomaly hunting ( Nicholas Wade and furin cleavage sites or Steven Quay and Richard Muller and CGGCGG , anyone?) in which any observed oddity in the nucleotide sequence of the virus was portrayed as clear-cut evidence of lab manipulation by scientists doing gain-of-function research (which, apparently, went very wrong), all coupled with an utter resistance to disconfirming evidence. It didn’t help, of course, that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) was not far from the wet markets that were first identified as likely sources of the outbreak and that the WIV was studying coronaviruses and thus had them on premises. Lab leak proponents are also fond of other kinds of conspiratorial thinking , such as attribution errors, weaponization of disagreements within a general consensus, shifting the burden of proof, moving the goalposts in response to disconfirming evidence, and others, all accompanied by an intense belief in a coverup at the highest levels of multiple governments.

Of course, conspiracy theories about a lab origin for a new pathogen (often as a “bioweapon” that somehow “leaked” from a biowarfare research lab) are nothing new. They inevitably arise whenever a deadly new pathogen appears to cause major outbreaks or, as in the case of SARS-CoV-2, a pandemic. It happened with HIV/AIDS, Ebola , and H1N1 . For instance, there was a major conspiracy theory about HIV/AIDS that involved its creation at Fort Detrick when scientists supposedly spliced together two other viruses, Visna and HTLV-1 and then tested the results on prison inmates. (Interestingly, this turned out to be a Russian propaganda operation codename Operation INFEKTION designed to blame the AIDS pandemic on the US biological warfare program.) Other conspiracy theories include claims that HIV had contaminated various vaccines (smallpox, hepatitis B, etc., depending on the specific version of the conspiracy theory) and thereby gotten into the population. It’s therefore no surprise that almost as soon as SARS-CoV-2 was identified as the source of the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China so did conspiracy theories about a lab origin for the virus, among other things.

One of the earliest conspiracy theories had arisen by February 2020, when James Lyons-Weiler claimed to have “ broken the coronavirus code “, claiming the novel coronavirus whose nucleotide sequence had been published a week or two before, was actually the result of a failed attempt to develop a vaccine for SARS, the coronavirus-caused disease that nearly became a pandemic in 2002-2003. Hilariously, he tried to claim that the novel coronavirus showed evidence of containing nucleotide sequences from a plasmid (a circular DNA construct into which scientists insert genes that can then be introduced into cells to get them to make the protein products of those genes), which, if true, certainly would have been slam-dunk evidence that SARS-CoV-2 had been created in a laboratory. Let’s just say that Lyons-Weiler, for all his claims of molecular biology expertise, made some rather glaring errors. Another variation on this theme was the claim that there were HIV sequences in the virus that indicated that the pandemic had come about as the result of a failed attempt to develop a vaccine against AIDS .