- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal

This article explores the ethical issues that may arise in your proposed study during your doctoral research degree.

What ethical principles apply when planning and conducting research?

Research ethics are the moral principles that govern how researchers conduct their studies (Wellcome Trust, 2014). As there are elements of uncertainty and risk involved in any study, every researcher has to consider how they can uphold these ethical principles and conduct the research in a way that protects the interests and welfare of participants and other stakeholders (such as organisations).

You will need to consider the ethical issues that might arise in your proposed study. Consideration of the fundamental ethical principles that underpin all research will help you to identify the key issues and how these could be addressed. As you are probably a practitioner who wants to undertake research within your workplace, consider how your role as an ‘insider’ influences how you will conduct your study. Think about the ethical issues that might arise when you become an insider researcher (for example, relating to trust, confidentiality and anonymity).

What key ethical principles do you think will be important when planning or conducting your research, particularly as an insider? Principles that come to mind might include autonomy, respect, dignity, privacy, informed consent and confidentiality. You may also have identified principles such as competence, integrity, wellbeing, justice and non-discrimination.

Key ethical issues that you will address as an insider researcher include:

- Gaining trust

- Avoiding coercion when recruiting colleagues or other participants (such as students or service users)

- Practical challenges relating to ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of organisations and staff or other participants.

(Heslop et al, 2018)

A fuller discussion of ethical principles is available from the British Psychological Society’s Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021).

You can also refer to guidance from the British Educational Research Association and the British Association for Applied Linguistics .

Ethical principles are essential for protecting the interests of research participants, including maximising the benefits and minimising any risks associated with taking part in a study. These principles describe ethical conduct which reflects the integrity of the researcher, promotes the wellbeing of participants and ensures high-quality research is conducted (Health Research Authority, 2022).

Research ethics is therefore not simply about gaining ethical approval for your study to be conducted. Research ethics relates to your moral conduct as a doctoral researcher and will apply throughout your study from design to dissemination (British Psychological Society, 2021). When you apply to undertake a doctorate, you will need to clearly indicate in your proposal that you understand these ethical principles and are committed to upholding them.

Where can I find ethical guidance and resources?

Professional bodies, learned societies, health and social care authorities, academic publications, Research Ethics Committees and research organisations provide a range of ethical guidance and resources. International codes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights underpin ethical frameworks (United Nations, 1948).

You may be aware of key legislation in your own country or the country where you plan to undertake the research, including laws relating to consent, data protection and decision-making capacity, for example, the Data Protection Act, 2018 (UK). If you want to find out more about becoming an ethical researcher, check out this Open University short course: Becoming an ethical researcher: Introduction and guidance: What is a badged course? - OpenLearn - Open University

You should be able to justify the research decisions you make. Utilising these resources will guide your ethical judgements when writing your proposal and ultimately when designing and conducting your research study. The Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research (British Educational Research Association, 2018) identifies the key responsibilities you will have when you conduct your research, including the range of stakeholders that you will have responsibilities to, as follows:

- to your participants (e.g. to appropriately inform them, facilitate their participation and support them)

- clients, stakeholders and sponsors

- the community of educational or health and social care researchers

- for publication and dissemination

- your wellbeing and development

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) has emphasised the need to promote equality, diversity and inclusion when undertaking research, particularly to address long-standing social and health inequalities. Research should be informed by the diversity of people’s experiences and insights, so that it will lead to the development of practice that addresses genuine need. A commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion aims to eradicate prejudice and discrimination on the basis of an individual or group of individuals' protected characteristics such as sex (gender), disability, race, sexual orientation, in line with the Equality Act 2010.

The NIHR has produced guidance for enhancing the inclusion of ‘under-served groups’ when designing a research study (2020). Although the guidance refers to clinical research it is relevant to research more broadly.

You should consider how you will promote equality and diversity in your planned study, including through aspects such as your research topic or question, the methodology you will use, the participants you plan to recruit and how you will analyse and interpret your data.

What ethical issues do I need to consider when writing my research proposal?

You might be planning to undertake research in a health, social care, educational or other setting, including observations and interviews. The following prompts should help you to identify key ethical issues that you need to bear in mind when undertaking research in such settings.

1. Imagine you are a potential participant. Think about the questions and concerns that you might have:

- How would you feel if a researcher sat in your space and took notes, completed a checklist, or made an audio or film recording?

- What harm might a researcher cause by observing or interviewing you and others?

- What would you want to know about the researcher and ask them about the study before giving consent?

- When imagining you are the participant, how could the researcher make you feel more comfortable to be observed or interviewed?

2. Having considered the perspective of your potential participant, how would you take account of concerns such as privacy, consent, wellbeing and power in your research proposal?

[Adapted from OpenLearn course: Becoming an ethical researcher, Week 2 Activity 3: Becoming an ethical researcher - OpenLearn - Open University ]

The ethical issues to be considered will vary depending on your organisational context/role, the types of participants you plan to recruit (for example, children, adults with mental health problems), the research methods you will use, and the types of data you will collect. You will need to decide how to recruit your participants so you do not inappropriately exclude anyone. Consider what methods may be necessary to facilitate their voice and how you can obtain their consent to taking part or ensure that consent is obtained from someone else as necessary, for example, a parent in the case of a child.

You should also think about how to avoid imposing an unnecessary burden or costs on your participants. For example, by minimising the length of time they will have to commit to the study and by providing travel or other expenses. Identify the measures that you will take to store your participants’ data safely and maintain their confidentiality and anonymity when you report your findings. You could do this by storing interview and video recordings in a secure server and anonymising their names and those of their organisations using pseudonyms.

Professional codes such as the Code of Human Research Ethics (BPS, 2021) provide guidance on undertaking research with children. Being an ‘insider’ researching within your own organisation has advantages. However, you should also consider how this might impact on your research, such as power dynamics, consent, potential bias and any conflict of interest between your professional and researcher roles (Sapiro and Matthews, 2020).

How have other researchers addressed any ethical challenges?

The literature provides researchers’ accounts explaining how they addressed ethical challenges when undertaking studies. For example, Turcotte-Tremblay and McSween-Cadieux (2018) discuss strategies for protecting participants’ confidentiality when disseminating findings locally, such as undertaking fieldwork in multiple sites and providing findings in a generalised form. In addition, professional guidance includes case studies illustrating how ethical issues can be addressed, including when researching online forums (British Sociological Association, no date).

Watch the videos below and consider what insights the postgraduate researcher and supervisor provide regarding issues such as being an ‘insider researcher’, power relations, avoiding intrusion, maintaining participant anonymity and complying with research ethics and professional standards. How might their experiences inform the design and conduct of your own study?

Postgraduate researcher and supervisor talk about ethical considerations

Your thoughtful consideration of the ethical issues that might arise and how you would address these should enable you to propose an ethically informed study and conduct it in a responsible, fair and sensitive manner.

British Educational Research Association (2018) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Psychological Society (2021) Code of Human Research Ethics . Available at: https://cms.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/BPS%20Code%20of%20Human%20Research%20Ethics%20%281%29.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

British Sociological Association (2016) Researching online forums . Available at: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/24834/j000208_researching_online_forums_-cs1-_v3.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Health Research Authority (2022) UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research . Available at: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/uk-policy-framework-health-social-care-research/uk-policy-framework-health-and-social-care-research/#chiefinvestigators (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Heslop, C., Burns, S., Lobo, R. (2018) ‘Managing qualitative research as insider-research in small rural communities’, Rural and Remote Health , 18: pp. 4576.

Equality Act 2010, c. 15. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/introduction (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (no date) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) . Available at: https://arc-kss.nihr.ac.uk/public-and-community-involvement/pcie-guide/how-to-do-pcie/equality-diversity-and-inclusion-edi (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Research (2020) Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: Guidance from INCLUDE project. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435 (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Sapiro, B. and Matthews, E. (2020) ‘Both Insider and Outsider. On Conducting Social Work Research in Mental Health Settings’, Advances in Social Work , 20(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.18060/23926

Turcotte-Tremblay, A. and McSween-Cadieux, E. (2018) ‘A reflection on the challenge of protecting confidentiality of participants when disseminating research results locally’, BMC Medical Ethics, 19(supplement 1), no. 45. Available at: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-018-0279-0

United Nations General Assembly (1948) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Resolution A/RES/217/A. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Drafted%20by%20representatives%20with%20different,all%20peoples%20and%20all%20nations . (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

Wellcome Trust (2014) Ensuring your research is ethical: A guide for Extended Project Qualification students . Available at: https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wtp057673_0.pdf (Accessed: 9 June 2023).

More articles from the research proposal collection

Writing your research proposal

A doctoral research degree is the highest academic qualification that a student can achieve. The guidance provided in these articles will help you apply for one of the two main types of research degree offered by The Open University.

Level: 1 Introductory

Defining your research methodology

Your research methodology is the approach you will take to guide your research process and explain why you use particular methods. This article explains more.

Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview

The final article looks at writing your research proposal - from the introduction through to citations and referencing - as well as preparing for your interview.

Free courses on postgraduate study

Are you ready for postgraduate study?

This free course, Are you ready for postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and ensure you are ready to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Succeeding in postgraduate study

This free course, Succeeding in postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

This free OpenLearn course is for psychology students and graduates who are interested in PhD study at some future point. Even if you have met PhD students and heard about their projects, it is likely that you have only a vague idea of what PhD study entails. This course is intended to give you more information.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 27 June 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Pebbles balance on a stone see-saw' - Copyright: Photo 51106733 / Balance © Anatoli Styf | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Camera equipment set up filming a man talking' - Copyright: Photo 42631221 © Gabriel Robledo | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Applying to study for a PhD in psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Succeeding in postgraduate study' - Copyright: © Everste/Getty Images

- Image 'Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal' - Copyright: Photo 50384175 / Children Playing © Lenutaidi | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview' - Copyright: Photo 133038259 / Black Student © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Defining your research methodology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Writing your research proposal' - Copyright free

- Image 'Are you ready for postgraduate study?' - Copyright free

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

Research Design Review

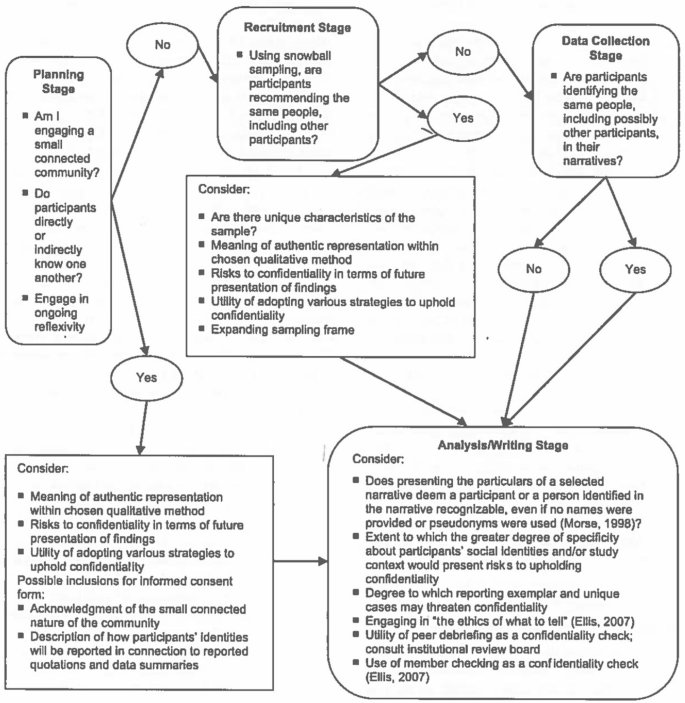

A discussion of qualitative & quantitative research design, writing ethics into your qualitative proposal.

Every research proposal for studying human beings must carefully consider the ethical ramifications of engaging individuals for research purposes, and this is particularly true in the relatively intimate, in-depth nature of qualitative research. It is incumbent on qualitative researchers to honestly assure research participants their confidentiality and right to privacy, safety from harm, and right to terminate their voluntary participation at any time with no untoward repercussions from doing so. The proposal should describe the procedures that will be taken to implement these assurances, including gaining informed consent, gaining approval from the relevant Institutional Review Board, and anonymizing participants’ names, places mentioned, and other potentially identifying information.

Special consideration should be given in the proposal to ethical matters when the proposed research (a) pertains to vulnerable populations such as children or the elderly; (b) concerns a marginalized segment of the population such as people with disabilities, same-sex couples, or the economically disadvantaged; (c) involves covert observation that will be conducted in association with an ethnographic study; or (d) is a narrative study in which the researcher may withhold the full true intent of the research in order not to stifle or bias participants’ telling of their stories.

Furthermore, the researcher should pay particular attention to ethical considerations when writing a proposal for a focus group study. The focus group method (regardless of mode) brings together (typically) a number of strangers who are often asked to offer their candid thoughts on personal and sensitive topics. For this reason (and other reasons, e.g., the moderator may be sharing confidential information with the participants), it is important to gain a signed consent form from all participants; however, the reality is that there is no way the researcher can totally guarantee confidentiality. These and other associated ethical considerations should be discussed in the Design section of the focus group proposal.

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: The TQF Qualitative Research Proposal: Limitations | Research Design Review

- Pingback: The TQF Qualitative Research Proposal: The Research Team | Research Design Review

- Pingback: The Total Quality Framework Proposal: Design Section — Credibility | Research Design Review

Great article! Ethical considerations become even more significant as we incorporate more and more technology.

- Pingback: Writing Ethics Into Your Qualitative Proposal | Managementpublic

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Research Whisperer

Just like the thesis whisperer – but with more money, how to write a successful ethics application.

She has a particular interest in tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, adolescent health, and the health of people in criminal justice settings.

Kat advises colleagues from diverse backgrounds on research ethics, study design, and data analysis.

She tweets from @epi_punk .

The word “ethics” strikes fear into the hearts of most early career researchers.

Some of the reasons are beyond our control, but there’s actually a lot we can do to make our own experiences of the ethics approval process less painful.

I’m writing this from two perspectives: as an early career researcher (I finished my PhD in 2019), and as a committee member (I’ve sat on an ethics advisory group since the start of my PhD in 2014).

The job of ethics committees is to identify the possible risks in a project, and then assess whether the research team:

- are aware of the risks.

- are taking appropriate steps to minimise them.

- have a plan to handle anything that does go wrong.

To do this, ethics committees need information. If you want your ethics application to get through the process as quickly as possible, you need to give the committee enough detail so that they understand your project and how you are managing any risks.

Getting your application as right as possible the first time makes the whole process go more quickly. If you don’t provide enough information, the committee will come back with questions. You may need to resubmit your application to the next meeting, which could be a month or two away.

Spending more time on your application for the first meeting can save you months later on!

Here are the main questions ethics committees will ask themselves when they assess your project:

- Are there any risks to the researchers? (e.g. Injuries in the lab, safety risks travelling to study sites, exposure to distressing topics during interviews or data analysis.)

- Are there any risks to the study participants? (From the study procedures themselves; risks to their privacy; risks of distress if they are asked about or exposed to upsetting content)

- Are there any risks to third parties? (i.e. people who aren’t directly participating)

- Could anybody’s privacy be invaded by the data collection process?

- Are there other staff in a lab who might be hurt if there were an accident?

- Are the research team aware of these risks, are they taking steps to minimise them, and do they have a plan if things go wrong?

The only way for the ethics committee to assess this is from the information you put into your application. Carefully think through your project and ask yourself those questions. And then put all of the answers into your application.

Here’s an example:

I am planning a project at the moment that involves interviewing health care providers about vulnerable people that they work with.

What are the risks to me? There aren’t any physical safety risks – I’ll be sitting in my office on the phone.

What about psychological risks? Could I be distressed by the content of the interviews? It’s possible. Some of the people I’ll interview are working with clients who have experienced child abuse, and some of their stories about their work might be upsetting.

What am I doing about these risks? I’m conducting interviews on the phone, rather than travelling to other people’s workplaces or homes. I won’t ask specifically about any distressing topics (minimising the risk), although they might come up anyway. If I get upset about the content of the interviews, I will probably be okay: I’ve worked in this area for many years, and I have strategies for dealing with it when my work upsets me (taking a break, talking to a colleague on the same project later on to help me process my feelings about it).

All of this goes into my application! I don’t write “I will conduct interviews with providers” and then say there are no risks, or that I have managed the risks. I give the committee all the details about each of the foreseeable risks I’ve identified, and exactly what I’m doing about them.

What about the risks to my participants? They could also find the content of the interviews upsetting. Again, my interview tool doesn’t ask directly about any distressing topics (minimising the risk), but it may come up. What’s my plan if my participants get upset? I’ll offer to change the topic, take a break, or stop the interview entirely. I mention this risk in the consent form, and the form will tell participants that they will have these options if they feel distressed. I will repeat this to them verbally at the start of the interview, and remind them that they don’t need to discuss anything with me that they don’t want to. Again, all these details go into my application.

What about risks to other people? Some health care providers might tell me private or sensitive information about their clients, by giving me specific examples instead of talking in general terms. To avoid this, I will ask them at the start of the interview not to talk about specific individuals, but to rather keep their answers general. If a participant does start to talk about an individual, I’ll remind them that this isn’t appropriate. I’ll also erase that part of the recording later on, so that those information isn’t transcribed. Again, all these details go into my application so that the ethics committee can see that I’m aware of the risk and I have a plan to manage it if it occurs.

As a committee member, I see applications get into trouble for a few common reasons.

The first is a lack of information , giving a very brief description of what will be done, without enough detail for the committee to understand the risks and what is being done about them.

The second is inconsistency , when a researcher says one thing on their application form, and something else in their consent form. Check carefully for consistency across all your documents before you submit.

A third is when a researcher proposes to do something that directly goes against the national ethical standards for research (e.g. collecting data without consent when they could get consent, or storing sensitive data in an insecure manner). Do not do this.

Some general tips:

- Find out the deadlines for your committee now, and start your application well in advance. It’s very hard to do a good job at the last minute, especially if you need details from your supervisor or other people in the project.

- Ask a colleague for a previous successful application for a similar project. Take note of the risks they identified, and how they managed them. Look at their consent forms and other documents, and see what you can adapt and reuse.

- Use grant applications for the project as a source of information on background, aims, methods, and outcomes. The format and level of detail required by the ethics committee is often similar.

- Read your country’s ethical guidance for research projects: this is what the ethics committee is working off. Think about which issues apply to your project, and how you can meet each of the standards. Spell this out for the committee.

- Find out whether your institution has specific requirements regarding wording in consent forms, storage of data, handling chemicals in the lab, etc. In your application, tell the committee that you are aware of these requirements and say how your project will meet them. Make sure that your consent forms and other documents are consistent with your institution’s standards. If your institution offers templates, use them!

- Ethics committees also assess the technical soundness of the research because poor quality research wastes time and resources, and exposes people to risks that aren’t justified by adequate benefits. Most committees include statistician and methods experts specifically for this reason (I’m one of them). Give a detailed explanation of your methods, and make sure they are appropriate to your research question. Get advice from a methods expert or a statistician to check that your project is sound – it’s much better to identify problems at the planning stage, rather than after you’ve gotten approval and collected your data.

- If you are doing an application for the first time, get help from your supervisor or thesis advisor. They shouldn’t make you do the application on your own. The more help you can get before you submit, the more quickly your project will get approved.

Share this:

Also I suggest doing the ethics training offered by your institution, or professional body. Recently I attended ANU’s Human Ethics training session. While I occasionally teach ethics, and have been a Chief Investigator on a project, I still found it useful. https://services.anu.edu.au/training/aries-human-ethics-training-sessions

Another useful resource is The Research Ethics Application Database (TREAD), an online database of successful research ethics applications from around the world, some of which include supporting documents such as consent forms and information sheets. (TREAD is also glad to have new submissions so if you have made a successful application, please consider sharing your paperwork – fully anonymised of course.) Info here https://tread.tghn.org/

Like Liked by 1 person

[…] Writing your ethics application? Here’s some tips! […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Library Guides

Dissertations 4: methodology: ethics.

- Introduction & Philosophy

- Methodology

Research Ethics

In the research context, ethics can be defined as "the standards of behaviour that guide your conduct in relation to the rights of those who become the subject of your work, or are affected by it" (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill 2015, p239).

The University itself is guided by the fundamental principle that research involving humans and /or animals and/or the environment should involve no more than minimal risk of harm to physical and psychological wellbeing.

Thus, ethics relates to many aspects of your research, including the conduct towards:

The participants of your primary research (experiments, interviews etc). You will need to explain that participation is voluntary, and they have the right to withdraw at any time. You will need the participants' informed consent. You will need to avoid harming the participants, physically as well as mentally. You will need to respect the participants’ privacy and offer the right to anonymity. You will need to manage their personal data confidentially, also according to legislation such as the Data Protection Act 2018. You will need to be truthful and accurate when using the information provided by the participants.

The authors you have used as secondary sources. You will need to acknowledge their work and avoid plagiarism by doing the proper citing and referencing.

The readers of your research. You will need to exercise the utmost integrity, honesty, accuracy and objectivity in the writing of your work.

The researcher . You will need to ensure that the research will be safe for you to undertake.

Your research may entail some risk, but risk has to be analysed and minimised through risk assessment. Depending on the type of your research, your research proposal may need to be approved by an Ethics Committee, which will assess your research proposal in light of the elements mentioned above. Again, you are advised to use a research methods book for further guidance.

Research Ethics Online Course

Introduction to Research Ethics: Working with People

Find out how to conduct ethical research when working with people by studying this online course for university students. Course developed by the University of Leeds.

- << Previous: Methods

- Next: Methodology >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2022 12:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/methodology-for-dissertations

CONNECT WITH US

Ethics statement examples - ESRC

Introduction.

Proposals submitted to the ESRC must provide a full ethics statement that confirms that proper consideration has been given to any ethics issues raised. All ESRC-funded grants must be approved by at least a light-touch ethics review.

The ESRC does not require a favourable ethics opinion to be secured prior to submission of a research proposal. However, a proposal must state what the applicant considers to be the possible ethics implications throughout the research project lifecycle, what measures will be taken for ongoing consideration of ethics issues, what review will be required for their proposed research and how and when it will be obtained.

Risk and benefit to researchers, participants and others (for example, potentially stigmatised or marginalised groups) as a result of the research and the potential impact, knowledge exchange, dissemination activity and future re-use of the data should also be considered as part of the ethical statement.

If an ethics review is required at a later stage in the project, this should be discussed and funding arrangements agreed in advance with the ESRC. At a minimum we expect that ethics review will be undertaken prior to the stage in the project that the actual research is carried out.

During peer review, reviewers and assessors will be asked to consider the ethical statement in the proposal. If they disagree with the proposed approach to ethics issues, or the statement does not adequately address these issues, this could lead to the rejection of a proposal, or the award of a conditional grant to ensure the necessary ethical considerations and ethical review are undertaken.

Last updated: 28 January 2022

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

Research Ethics Step by Step

- Open Access

- First Online: 15 September 2020

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Jaap Bos 4

42k Accesses

After Reading This Chapter, You Will:

Have a general knowledge of Institutional Review Board (IRB) procedures

Have the capacity to anticipate the basic ethical pitfalls in research designs

Know how to counter common ethical objections

Be able to design an informed consent form

This chapter has been co-authored by Dorota Lepianka.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

- Added value

Anonymization

- Avoiding harm

- Conflicting loyalties

- Cost-benefit analysis

- Data management

- Data storage

- Equitability

- Ethics creep

- Expenditures

- False negatives

- False positives

- Gatekeepers

- Informed consent

- Intrusive questioning

- Invasion of integrity

Pseudonymization

- Reciprocity

- Responsibility

- Risk assessment

- Seeking justice

- Vulnerability

1 Introduction

1.1 research design and ethical approval.

In this chapter, we aim to guide you through some of the most important ethical issues you may encounter throughout the process of finalizing your research design and preparing it for the process of ethical approval. The issues discussed here range from broad topics about the relevancy of the research itself, to detailed questions regarding confidentiality, establishing informed consent, briefing and debriefing research participants, dealing with invasive techniques, deception, and safe storage of your data.

The majority of these ethical dilemmas coincide largely with the concerns voiced by independent Institutional Review Boards (IRBs, also referred to as Research Ethics Committees , or RECs). IRBs register, review, and oversee local research applications that involve human participants. They are established to protect the rights of research participants and to foster a sustainable research environment. The task of such boards is to evaluate whether or not a research design meets the institutional ethics standards and facilitates a necessary risk assessment .

The necessity of ethical reviewing is reflected in national laws as well as international declarations and has become a mandatory procedure in universities and research institutes worldwide (see Israel 2015 , for an overview of ethical reviewing practices). Failing to seek the approval of an IRB can have serious consequence for the researchers involved. For example, the retraction note attached to an article on bullying, published in 2017 in the International Journal of Pediatrics revealed ‘The study was conducted in agreement with the school principal and the authors received verbal approval, but they did not receive formal ethical approval from the designated committee of the Ministry of Education ’ (entry at ‘Retraction Watch’, March 13th 2019).

A number of scholars focusing on ethical review processes have critiqued the institutionalization of ethical reviewing, because, as one author observed, it seems to assume that unscrupulous researchers are restrained only by the leash and muzzle of the IRB system (Schneider 2015 , p. 6).

Indeed, by setting aside ethics as a separate issue and submitting it to an ‘administrative logic’ (procedural, formalistic approach), scholarly research has fallen prey to a form of ethics creep , a process whereby the regulatory system expands and intensifies at the expense of genuine ethical reflection (Haggerty 2004 ). Scott ( 2017 ) remembers how a simple study once was killed by such formalistic procedures. Understandably, researchers sometimes see the completion of an IRB application form to be a mere ‘formality, a hurdle to surmount to get on and do the research’ (Guillemin and Gillam 2004 , p. 263).

We agree that ethical considerations should inform our discussions about research, and that these discussions should not be obstructed by regulatory procedures. The aim of this chapter is therefore to assist you in your ethical deliberations. This chapter seeks to guide you through the process of making important ethical decisions at all stages of formulating a research design, and to help you identify the common pitfalls, objections, and critiques. To facilitate this process, we have designed a series of queries at the end of each paragraph, that could be taken into consideration whenever you plan to carry out a research project. Not all questions may be relevant to all research projects, but as a whole, they should facilitate a fairly thorough preparation.

In the sections to follow, we map out the various ethical dimensions of designing a research project step by step: addressing the fundamental question of why and for whom we do research (Sect. 10.2 ); an exploration of the ethical considerations of the research design itself, including the recruitment of study participants (Sects. 10.3 and 10.4 ); violation of integrity (Sect. 10.5 ); avoiding deception (Sect. 10.6 ); informed consent (Sect. 10.7 ); collecting data during field work (Sect. 10.8 ); what to do with incidental findings (Sect. 10.9 ); analyzing collected data (Sect. 10.10 ); reporting and dissemination of research findings (Sect. 10.11 ); and finally data management and storage (Sect. 10.12 ). This chapter closes with a summary (Sect. 10.13 ) and we include a brief ethics checklist and offer a model informed consent form that can be used in the future to help you cross all your ‘t’s and dot all your ‘i’s (Box 10.1 ).

We highlight our discussions with multiple case studies selected from a wide range of disciplines within the social sciences, including specializations within psychology, anthropology, educational sciences, interdisciplinary studies, and others. For the sake of brevity, we refrain from seeking examples from all disciplines for each individual dilemma, but instead focus on those that seem most poignant. We hope this overview will prepare you to face the rigors of research with confidence.

Box 10.1: Rules of Thumb for Ethical Assessment of Research Designs

Avoiding Harm Researchers have a responsibility to ensure that their study does no harm to any participants or communities involved. They also need to assess the risks that participants (and communities) may face.

How likely is your research project to cause harm to the individuals or communities you choose to research? How serious is the possible harm? What measures need be taken to offset the risks? Is there any way in which harm could be justified or excused? How do you ensure that your study does not endanger the values, cultural traditions, and practices of the community you study?

Doing Good Researchers have the complementary obligation to do research that contributes to the furthering of others’ well-being.

Who are the beneficiaries of your study? What specific benevolence might flow from it and for whom? What can participants reasonably expect in return from you and what should you offer them, if anything? What does your study offer to promote the well-being of others? How does the community or society at large benefit?

Seeking Justice Finally, researchers should ensure that participants are treated justly and that no one has been favored or discriminated against.

Do you treat your participants fairly and have you taken their needs into consideration? How do you ensure a fair distribution of the burdens and benefits in both the participant’s experience and research outcomes? How are the (perhaps contradictory) needs of the communities taken into account?

Whereas all three criteria seem ‘self-evident’ if not trivial, there remains the critical and difficult question of how to interpret them, and whether they apply in any given case (i.e. everybody will agree that one should not harm people and do good or seek justice but what does this mean in practice?). For further discussion, see Beauchamp and Childress ( 2001 ), Principles of Biomedical Ethics .

2 Relevancy: Choice of Research Area

2.1 what for.

There are few subjects or questions that researchers cannot study, but are they all worth researching? That is a different question. Contrary to what you may think, completely new research questions do not exist. Research builds upon the pre-existing research lexicon. In fact, researchers have an obligation to enhance or critique theories, improve established bodies of knowledge, and adapt or alter relevant methodologies.

Failing to acknowledge research traditions may come with the risk of wasting valuable resources, but also of self-disqualification. The relevancy of a research project is thus not so much measured in terms of how much knowledge it generates, but rather in how much knowledge it generates in relation to what is already known (see the imperative of originality, discussed in Chap. 2 ).

2.2 For Whom?

Some research is fundamental – for the sake of knowledge – but most is not. Often, results have certain practical uses for other parties, sciences’ stakeholders . They can be commissionaires who act as patrons of research projects, professionals working in a ‘field of practice’ who make use of scientific knowledge, or their clients. Research can have implications for policy makers, teachers, therapists, professionals working with minority groups, or indeed, minority groups themselves, to name but a few.

The question how research projects impact various (potential) stakeholders is not always explicitly addressed, but we feel that this is something that deserves careful attention. Who is addressed, who will be influenced, and who can make use of research in which ways? Consider the following two examples where the stakeholders are specifically targeted and even addressed.

Ran et al. ( 2003 ) describe a comparative research study into the effectiveness of psychoeducational intervention programs in the treating of schizophrenics in rural China. The program specifically targets patients’ relatives, who, the researchers conclude, need to improve their knowledge of the illness and change their attitude towards the patient.

A qualitative study on experiences with prejudice and discrimination among Afghan and Iranian immigrant youth in Canada singles out the media as a ‘major contributor to shaping prejudicial attitudes and behaviors,’ and schools as one of the first places youth may encounter discrimination (Khanlou et al. 2008 )

2.3 At What Cost?

Thirdly, there is the question of balancing costs and benefits of research. Costs comprise of salaries, investments, use of equipment, but also of sacrifices or (health) risks run by all those involved. Benefits can be expected revenue and earnings, but also gained knowledge and expertise, certain privileges allotted to participants, or even access to particular facilities.

The fact that the costs and benefits can be of a material and immaterial nature makes them both difficult to measure and predict (see Diener and Crandall 1978 ). How do you value and weigh costs and benefits? Who should profit and who should run which risks?

While there is no way to answer these questions in general, there are different models that you can use to assess risks and benefits, based on what you think counts as important.

In the first model, science is committed to the principle of impartiality . Researchers and research participants partake in research primarily because they value science, want to promote its cause, and feel that their contribution helps further scientific knowledge. In this model, costs consist just of the salaries of the researchers and the marginal compensation of the participants for their time. Knowledge acquisition is the most important gain, and risks are understood in the immediate context of research (health hazards).

In the second model, knowledge production is regarded as a commercial activity. Universities and their researchers are seen as entrepreneurs who collaborate with other parties (mainly industry and government) and are committed to the principle of profit . In this model, costs are seen as investments, gains as (potential) revenues. Compensation of participants is an expense item and any risks they run can be ‘bought off.’

The third model proposes knowledge production from the principle of equitability (fairness for all). It accepts that knowledge may be profitable, but rejects a one-sided distribution of gains, where all the profits (patents, publication, prestige, grants) go to the researchers only, and none to the participants. Participants should not merely be monetarily compensated, but profit in a much more direct way, for example by giving them access to health facilities, providing better knowledge of the topic in question (Anderson 2019 ) or even empowering whole communities (Benatar 2002 ).

These different models not only perceive parties or stakeholders differently, they also perceive of risks, costs and benefits differently. Consequently, researchers may come to weigh the costs, benefits, and risks differently depending on what they value most (Box 10.2 ).

Box 10.2: Fair Compensation?

In a research application for a study on coping with undesirable social behavior at the workplace in China, the researchers planned to ask participants to complete a questionnaire which was estimated to takes up to 15 min. Participants would receive ¥8 (roughly 1 Euro) in compensation for their effort, but only once they completed the questionnaire. When queried by their local IRB why every participant wouldn’t be compensated regardless, rather than only those who complete the questionnaire, the researchers presented four arguments:

Rewarding participation before finishing the research leads to high dropout rates

It is difficult to organize payment with non-completers

The questions are non-invasive

In comparable cases, applications are always approved by IRBs

Evaluate these responses by ranking the arguments. Which argument do you find most and which least convincing, and why?

(Case communicated to one of the authors of this chapter)

2.4 Trauma Research: A Case in Point

Consider the question of whether research on traumatic experiences itself should be regarded as harmful. It is argued, on the one hand, that asking about traumatic experience is risky, as survivors may be more vulnerable and easier to stigmatize. On the other hand, there is also evidence that suggests that talking or writing about traumatic experiences can in fact be beneficial, psychologically as well as physiologically (Marshall et al. 2001 ). How does one weigh the (potential) risks against the (possible) benefits (DePrince and Freyd 2006 )?

In a study among 517 undergraduate students, Marno Cromer et al. ( 2006 ) asked subjects to rate how distressing it was for them to discuss a range of traumatic experiences and found that a vast majority did not find it difficult at all. However, argued the authors sensibly, it’s not the average that counts here, but the exception . And indeed, 24 participants reported the trauma research to be ‘much more distressing’ than everyday life. Of these 24, all but one still believed the research to be important enough to be carried out. The one exception reported that the research seemed ‘a somewhat bad idea.’

These findings concur with Newman et al. ( 1999 ), who did research on childhood abuse and found that a minority of the respondents reported feeling upset after the research. Of these, a few indicated that they would have preferred to have not participated had they known what the experience would be like.

In weighing the (immaterial) benefits against the costs of talking about traumatic experiences (distress), the former were deemed to outweigh the latter, provided that interviewers are carefully selected and trained.

Of note, however, one consideration is left out of this comparison, namely the question of whether not doing the research should be considered a risk (Box 10.3 ). Indeed, Becker-Blease and Freyd ( 2006 , p. 225) reason that ‘silence is part of the problem’, and there is a real ‘possibility that the social forces that keep so many people silent about abuse play out in the institution, research labs, and IRBs.’

Will the cost-benefit balance shift if the risk of not doing research be taken into consideration?

Q1: What is the added value of my research project and for whom does it benefit?

Which research traditions and methodologies do I relate to and why?

Who is addressed by my research project (who are my possible stakeholders)?

Which costs and benefits can be expected, for whom, and how do I balance them?

3 Choice of Participants

3.1 ethical limitations in choice of participants.

Researchers must make many decisions regarding the choice of participants. Is the sample randomly selected and does it give a fair representation of the population? Will the N be large enough to test my hypothesis? Has non-response been taken into account? Et cetera. Some of these methodological questions have ethical consequences, as we will explore below.

3.2 Number of Participants

This is of ethical concern because research is considered (at least to a degree) a burden on participants and often times on society at large as well. The number of participants should therefore be no more than absolutely necessary.

In quantitative studies, a reasonable estimate can be given with a power analysis . ‘Statistical power’ in hypothesis testing signifies the probability that the test will detect an effect that actually exists. By calculating the power of a study, it becomes possible to determine the required sample size, given a particular statistical method, and a predetermined degree of confidence. For example, to detect a small interaction effect between two variables, using a linear mixed-effect method, a sample of N = 120 would suffice at a default alpha of.05. Remaining space in this book does not permit a detailed discussion of how to calculate the power of a study, but see Cohen 1988 , for an explanation of power in the behavioral sciences in general.

In qualitative studies, no such power analysis would be suitable. Instead, the principle of saturation is often used. Saturation implies approaching new informants until enough knowledge is gained to answer the research question, or until the categories used are fully accounted for. What exactly constitutes ‘saturation’ may differ from one field of expertise to the next and may need further problematization moving forward (see O’Reilly and Parker 2012 ).

3.3 Selection of Participants

Laboratory studies often use undergraduate students as research subjects (usually in exchange for ‘credits’). These are called subject pools . In some fields of research in the social sciences, subject pools make up the majority of research participants, as Diener and Crandall ( 1978 ) pointed out long ago.

Convenience sampling (using groups of people who are easy to contact or to reach) not only has methodological drawbacks, but also ethical implications. Heinrich, Heine, and Norenzayan ( 2010 ) called attention to the social science’s ‘usual subjects’ and named them WEIRDOs, an acronym for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and coming from Democratic cultures.

They maintain that WEIRDOs aren’t representative of humans as a whole, and that psychologists shouldn’t routinely use them to make broad claims about the drivers of human behavior because WEIRDOs differ in fundamental aspects with non-WEIRDOs. Different cultural experiences result in differing styles of reasoning, conceptions of the self, notions of fairness, and even visual perception.

Box 10.3: Risks and Benefits

Risk : The probability of harm (physical, psychological, social, legal, or economic) occurring as a result of participation in a research study. The probability and the magnitude of possible harm may vary from minimal (or none) to significant.

Minimal Risk : A risk is considered to be minimal when the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the proposed research are not greater, in and of themselves, than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examination or tests.

Benefit : A valued or desired outcome, of material or physical nature (i.e. money, goods), or immaterial nature (i.e. knowledge, skills, privileges). Individuals may not only benefit from the research, but also communities as a whole.

(Adapted from the Policy Manual of the University of Louisville.)

3.4 Online Communities

As a specific target group for research, online communities pose their own dilemmas. Legally, researchers must be aware that they may be bound by the ‘general terms and conditions’ of these online platforms, which can restrict the use of their data for research purposes. Morally, it is important to ask whether it is right to record the activities of an online public place without the participant’s consent, regardless of whether it is allowed (see Chap. 7 for a discussion of this question). There are two viewpoints we will explore on this matter.

Oliver ( 2010 , p. 133) argues that although communication in an online environment may be mediated in different ways, it is still communication between people. In essence, the same ethical principles should apply, including the receipt of active consent.

Burbules ( 2009 , p. 538) on the other hand, argues that in online or web-based research, notions regarding privacy, anonymity, and the right to ‘own’ information needs to be radically reconsidered.

What matters online, Burbules argues, is not so much anonymity, but rather access. In the digital universe, people want to share information. But they also want to control who can make use of it. A challenging dichotomy to navigate indeed.

This problem (the question of who can access which data) has become even more urgent today. This urgency can be traced to new information and communication technologies that enable researchers to build extremely complex models based on massive and diverse databases, allowing increasingly accurate predictions about an individual’s actions and choices.

3.5 Control Groups

Research on the effects of certain interventions that involve control groups (participants who receive either less effective or no treatment) leads to the question of whether it is fair for a participant to be placed in a disadvantageous position.

This is referred to as asymmetrical treatment . The question is grounded in considerations of egalitarian justice , which is in other words, the idea that individuals should have an equal share of the benefits, rather than just the baseline avoidance of harm.

It is suggested that participants in the control group be offered the more effective treatment once the study is completed (Mark and Lenz-Watson 2011 ). A problem with this being that it applies to certain research designs only (typically RCT, or ‘Randomized Controlled Trial’) and not to others (policy interventions, for example, or education; for further discussion, see Diener and Crandall 1978 ). With research on policy interventions, (as opposed to treatment research), the question is whether or not it is fair to offer certain policies to certain groups and not to others.

Q2: Who are the participants in my research project?

Which ethical consequences may be involved in selecting participants for my research project?

How do I ensure that my selection of participants does not result in unfair treatment?

4 Vulnerable Participants

4.1 vulnerable participants.

Vulnerable participants are properly conceived of as those who have ‘an identifiably increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater wrong’ (Hurst quoted in Bracken-Roche et al. 2017 ). Seeking the cooperation of vulnerable people may be problematic for various reasons, but that does not imply that they cannot or should not be involved in research. It does mean that these groups need special attention, however.

4.2 Minors and Children

Working with minors and children requires consideration from both a moral and a legal perspective. Often in place are somewhat arbitrary age limits that will differ from country to country, which require that researchers seek active consent from the parents or legal representatives of a child. This says little, however, about the minor’s moral capacity to participate in research.

IRBs generally acknowledge that children can be involved, but that different age-groups should be treated on par with their stages of psychological development, that will inform what a six-year-old or a twelve-year-old child can or cannot do, or what an eight-year-old is capable of comparatively. In general, the younger the child, the shorter and less intense the inquiry should be.

We concur with Schenk and Rama Rao ( 2016 , p. 451) who argue that young children should be excluded from providing detailed information on potentially traumatic topics that may cause strong emotional distress. As is usually the case, exceptions can be made under particular circumstances, but they remain outliers. We also agree with Vargas and Montaya ( 2009 ) that it is sensible to consider any contextual and cultural factors, as this may make a difference in a child’s understanding of the research environment.

Finally, we emphasize that researchers who work with minors (children) should have special training on how to interview or collect data from them.

4.3 Disadvantaged Participants

When cognitively impaired individuals are included in a research design, special attention must be paid to the potential level of invasiveness, the degree of risk, the potential for benefit, and the participant’s severity of cognitive impairment (Szala-Meneok 2009 ). Likewise, people who are in dependent circumstances (such as detainees, elderly people in nursing homes, or the unemployed), may not always have the capacity to refuse consent, or may fail to understand that they have the power to refuse cooperation. A reasonable assessment regarding the perceived ability to participate and to refuse participation must thus be made for every case in which these populations are involved (see Box 10.4 for an overview of vulnerable participants).

4.4 Mixed Vulnerability

At times, several forms of vulnerability coincide within one research proposal. Consider as a case in point a proposed study into health problems (suicidal ideation), sexual risk-taking behavior, and substance use of LGBT adolescents of between 16–17 years old, as reported by Brian Mustanski ( 2011 ). An Institutional Review Board (IRB) was hesitant to approve Mustanski’s application for a number of reasons. We will discuss those reasons below, together with Mustanski’s responses.

The first problem the IRB encountered was that the researcher was seeking a waiver for parental permission. Adolescents at this age are legally minors and any waiver requires the provision of an appropriate mechanism for protecting the minor. Mustanski argued, however, that the goal of waiving parental permission was not to circumvent the authority of parents. ‘Instead, it is to allow for scientists to conduct research that could improve the health of adolescents in cases where parental permission is not a reasonable requirement to protect the participating youth’ ( 2011 , p. 677).

The second concern of the IRB was the vulnerability of the LGBT community collectively, who have historically been more prone to stigmatization and discrimination. Mustanski replied that he knew of no evidence that demonstrated any decision-making impairment of members of the LGBT community, and that he believed many of them would be insulted to have it implied otherwise.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the IRB was worried that participants in this research might be exposed to sensitive information that could lead to psychological harm. Mustanski agreed that IRBs should have a role in protecting participants’ interests, but argued that IRBs tended to overestimate risks. This can lead to time-consuming procedures and the implementation of supposed protections that may mitigate the scientific validity of the research, or discourage future behavioral research involving certain populations. After a number of required adjustments (such as a more detailed risk assessment), the proposal was ultimately accepted.

Box 10.4: Vulnerable Populations by Category

Adapted with permission from the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board for Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia.

Q3: How do you ensure appropriate and equitable selection of participants?

Who are your research subjects?

Are your research subjects part of a vulnerable population, and if so, what risks do you anticipate?

Where do you expect to find them and how do you intend to recruit them?

5 Use of Invasive Techniques

5.1 invasive techniques.

By invasive techniques , we mean any procedure or intervention that affects the body or mind of a research participant such that it results in psychological or physical harm. Some argue that our definition of invasiveness should not be limited to individual participants but should include entire communities as well (Box 10.5 ).

Invasive techniques, by definition, violate the principle of nonmaleficence (‘do no harm’), and are among the most urgent concerns of IRBs the world over. However, harm is broadly (and vaguely) defined, ranging from trauma to strong disagreeable feelings, and from short-term to long-lasting. The European Textbook on Ethics ( 2010 , p. 200) defines harm as such: ‘To be harmed is to have one’s interests set back or to be made worse off than one would otherwise have been. Harms can relate to any aspect of an individual’s welfare, for example physical or social. Institutions can also be harmed insofar as they can be thought of as having interests distinct from those of their members.’

Invasive techniques may include exposure to insensitive stimuli, intrusive interrogation, excessive measurements, or any procedures that can cause damage. We exclude from our discussion any medical practices or intervention, such as administering drugs or the use of clinical health trials and refer anyone who intends to use these techniques to specialized Medical Research Ethics Committees (MRECs).

5.2 Examples of Invasive Research

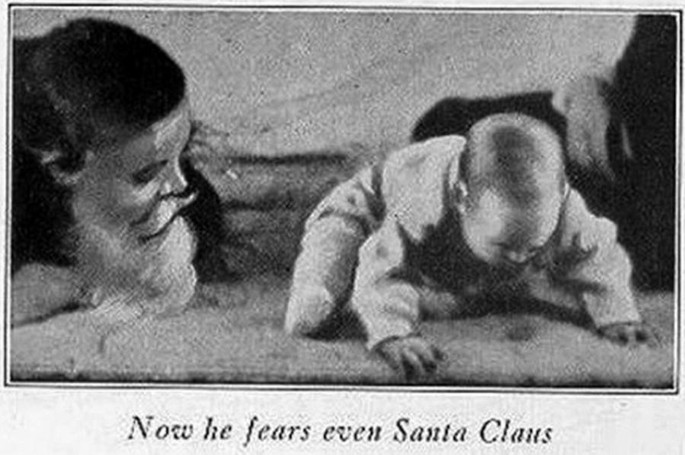

Some of psychology’s most famous experiments were hampered by the ethical quandaries of invasive research. For example, John Watson’s 1919 behavioral experiments with ‘Little Albert,’ an eleven-month-old child, who was exposed to loud, frightening sounds when presented with specific fearsome images. Although it is unclear what the net effects were on the child, by today’s standards, the design would be considered unethical for its gross lack on concern for the wellbeing of the child (see Harris 1979; Beck et al. 2009 ) (Fig. 10.1 ).

Little Albert . Still from the film made by Watson. (Source: Wikipedia)

Harry Harlow’s ‘Pit of Despair Studies’ from the 1950s involved infant primates who were raised in social isolation, without their protective mothers or with surrogate mothers (dolls). They consequently developed signs of what humans call ‘panic disorder.’ This complete lack of concern for animal welfare would certainly be considered unethical by today’s standards.

Psychologist Stanley Milgram’s well-known 1961 experiments, that involved participants who were led to believe that they were administering electric shocks to fellow participants are deemed invasive, despite the researcher attempting to minimize harm by debriefing his participants (see Tolich 2014 ).

Diana Baumrind ( 1964 ) was quick to recognize the ethical perils of the Milgram studies: ‘From the subject’s point of view procedures which involve loss of dignity, self-esteem, and trust in rational authority are probably most harmful in the long run and require the most thoughtfully planned reparations, if engaged in at all’ (p. 423).

5.3 Avoiding Invasive Routines?

Can (or should) invasiveness be avoided at all times? The answer seems obvious: no techniques that cause harm should be put to use. In practice, however, the answer is more ambiguous.

Some research topics are inherently ‘sensitive’ (i.e. psychological trauma, loss, bereavement, discrimination, sexism, or suicide). Merely discussing these subjects can be perceived as painful. Similarly, some techniques necessitate a physical response from participants and can result in some harm. Does that imply these subjects cannot be researched, and that these stimuli cannot be used? Not necessarily.

In an experiment that provides a telling example, researchers tried to establish the causal relationship between workload and stress response. To do so, they had to induce a potentially harmful stimulus, namely some form of stress. The results showed that such stimuli do indeed have an influence on a participant’s perceived well-being and impacted their physical health, as indicated by an increased cardiovascular response (see Hjortskov et al. 2004 ).

Is it justifiable to expose respondents to harmful stimuli, even when the effect is likely short-term? Hjortskov et al. answered the question in the affirmative and took refuge in what is considered by many as a safe baseline in research ethics. If harm does not exceed the equivalence of what can be expected to occur in everyday life, they argued, then the procedure should be safe.

It has been maintained that invasive techniques using stressors, unpleasant noises, rude or unkind remarks, among other forms of aggravators, are acceptable when (a) there are no other non-invasive techniques at hand, (b) the effects are equivalent to what people can expect to encounter in everyday situations, (c) have no long-lasting impact, and (d) everything is done to minimize harm.

Some retort that this will not (always) be sufficient. People who face systematic stigmatization in everyday life, or social exclusion, would be harmed in a way that is not acceptable should they be exposed to such stimuli, even though that is exactly what they expect to occur in everyday life.

Q4: Will the research design procedures result in any (unacceptable form of) harm or risk?

Which possible risks of harm are feasible in this research?

How do you plan to minimize harm (if any)?

Box 10.5: Invasive or Intrusive?

The term invasive originates from the medical sciences, where it means : entering the body, by cutting or inserting instruments . In the social sciences, it describes techniques that enter one’s privacy. Questions about one’s sexual orientation, political preferences, and other privately sensitive subjects are considered ‘invasive’, as is exposure to strong aversive stimuli or traumatizing experiences.

Intrusive was originally a legal term, described as entering without invitation or welcome . In the social sciences, it describes techniques that invoke ‘unwelcome feelings.’ Research may be regarded as ‘intrusive’ when it concerns topics that respondents dislike talking about or find difficult to discuss (Elam and Fenton 2003 , p. 16). Intrusive techniques can also involve prolonged procedures and processes that involve substantial physical contact. Intrusive questions can make a participant feel uneasy, uncomfortable, even shameful: ‘Are you anorexic?’ ‘Do you masturbate?’

Some examples of invasive and intrusive technique include:

EEG, PAT scans, CAT scans, (f)MRI, or measuring heart rate, are all non-invasive in the medical and psychological sense, but can be intrusive.

Questions about race, ethnicity, and sexual health can be both invasive and intrusive.

Queries about personal information, including name, date and place of birth, biometric records, education, financial, and employment history, are often thought to be neither invasive nor intrusive. However, to some people some of these questions can be intrusive. Regardless, use of this information is strictly limited under data protection regulation in most countries.

6 Deception

6.1 deceptive techniques.

Any research procedure in which a participant is deliberately provided with misinformation is labeled as a deceptive technique . Deception involves (a) giving false information, or (b) generating false assumptions, or (c) withholding any information that participants may request, or (d) withholding information that is relevant to appropriate informed consent (Lawson 2001 , p. 120). Just because early research on the harmfulness of deception does not indicate that deceived participants feel harmed (Christensen 1988 ) or that they become resentful (Kimmel 1998 ), does not mean it is without moral consequence.

By default, deception excludes consent (see below). Participants are therefore not at liberty to decide to participate (or to continue participating) on the conditions known to them, regardless of whether consent was given afterwards, or even whether participants agreed to be deceived beforehand (when they agree to be fooled in some way).

Deception thus suggests a possible breach of two important ethical principles: the protection of people’s autonomy and dignity, and the fair and equitable treatment of participants. Some have called for the abandonment of deception in research altogether, while others maintain that certain research areas, particularly in psychology, cannot do without it (see Christensen 1988 ). At any rate, IRBs have become more cautious in the last decade and generally insist on a full debriefing at minimum (see Mertens and Ginsberg 2009 , p. 331). But even a full debriefing may not always be possible.

To summarize: forms of deception include providing false or misleading information about:

Research goals or aims

Research setup

The researcher’s identity

The nature of a participants’ tasks or role

Any possible risks or consequences of participation.

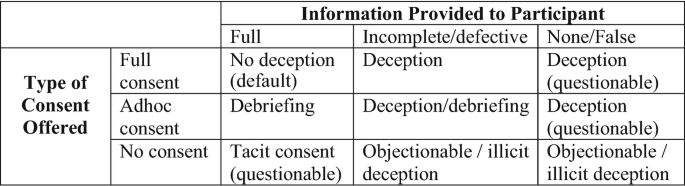

The distinction between false information and defective information is noteworthy. False information means presenting an (oftentimes completely) wrong picture of the true research goals, while defective or misleading information might only mean withholding some (key) aspects thereof. Some argue that not telling participants certain things is not a form of deception (Hey 1998 , p. 397), but we concur with Lawson ( 2001 ) that it certainly can be, especially on a relational level (pertaining to the relationship between researcher and participant) (Fig. 10.2 ).

Degrees of deception as a function of consent/debriefing and provision of information

6.2 Four Cases

Consider the following four cases in which (some form) of deception was deployed. How does the form and level of deception differ in these cases?

In the first, that came to the attention of one of the authors of this chapter, a group of researchers proposed to approach a number of intermediaries with mock job application letters and matching CV’s that differed only with respect to the ethnicity of the ‘applicant’. The researchers intended to measure the response rate of the intermediaries as an indication of hidden discrimination. The ‘participants’ (the intermediaries) were neither informed of nor debriefed about the research project, and thus would not be able to not participate or retort to its findings. Deception was deemed necessary to elicit true behavioral response.

The second pertained to an unpublished ethnographic study into social exclusion of the poor in Poland, carried out by one of the authors of this chapter. The researcher asked participants if they could be interviewed about their ‘lifestyles,’ deliberately not mentioning the goal of the study (social exclusion) because the researcher reasoned it might instill them (against their own conviction) with an idea that they are marginalized and excluded. The researcher feared that this idea would impose on them an identity that they could perceive as harmful. The research participants who were asked for consent were not informed about the true nature of the research project, nor were they debriefed afterwards. In this case, deception was considered both necessary as well as in the interest of the participants.

The third case concerns a covert participant observation project in an online anorexia support community performed by Brotsky and Giles ( 2007 ). The researchers created a mock identity of an anorexic young woman who said she wanted to continue losing weight. The researchers wanted to study the psychological support offered to her by the community, who was not informed about the research project. Throughout the course of the project, the invented character of the researchers developed close (online) relationships with some of its members. They justified the use of a manufactured identity on the grounds that if the purpose of the study was disclosed, access to the site would probably not be granted. Deception was deemed acceptable because of the ‘potential benefit of our findings to the eating disorders clinical field’ ( 2007 , p. 96). The research participants were never asked for their consent, nor informed about the nature of the research.

The fourth case concerns social psychology research into the bystander effect (the inclination not to intervene in a situation when other people are present). Experiments on the bystander effect rely heavily on giving false information about the roles of other participants involved in the study, because they are in reality in cahoots with the researcher.

In a recent study into the bystander effect, Van Bommel et al. ( 2014 ) wanted to know whether the presence of security cameras would have any influence on said effect. The researchers designed a realistic face-to-face situation featuring a security camera (not featured in the control group). They exposed participants to a mock ‘criminal act’ to see whether they would respond or not. Immediately afterwards, participants were informed of the true nature of the setup.

In all cases, some form of deception was considered necessary, though for different reasons. Deception contributes to inequity between the research and the participant. By debriefing the participant (i.e. informing them of the true nature or purpose of the research), some of this can be countered under certain circumstances. In the first case discussed above, debriefing was not considered, in the second it was ruled out. In the fourth case it was part of the design by default and not questioned as such. In the third case, it could (and some would argue should) have been used.

6.3 Deception and Misinformation

Arguably what matters most in considering the use of deception are found within two parameters: the degree of misinformation and the degree to which participants may give consent or can be debriefed (Ortmann and Hertwig 2002 ) (see Fig. 10.3 ). The questions any researcher must answer regardless are (1) whether or not it is really necessary to use deception, and (2) how to repair inequity if it were to be used.

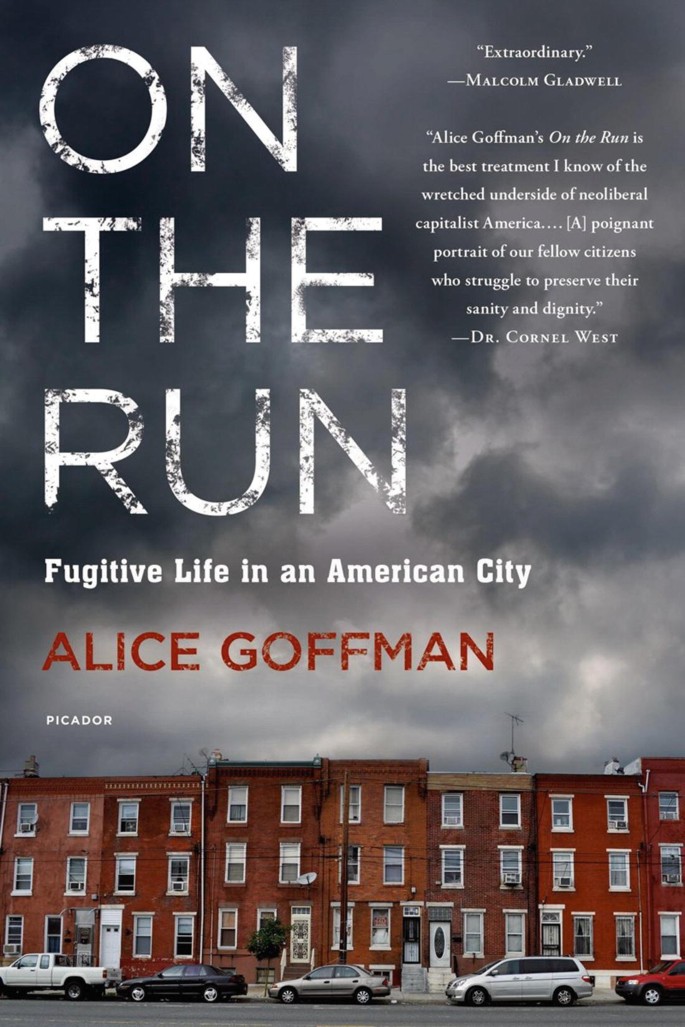

Alice Goffman, On the run

Q5: Will the research design provide a full disclosure of all information relevant to the participant? If not, why not?

How do you ensure your participants are adequately informed?

What do you do to prevent deception?

Box 10.6: Checkbox for Ethical Concerns in Social Sciences Research Design

Which research techniques do you use in your design, and to what extent is your design vulnerable to the ethical concerns above? Provide a detailed description.

7 Informed Consent

7.1 informed consent protocols.

Following established informed consent protocols are indispensable in any scientific research and serve to ensure that research is carried out in a manner that conforms to international regulations (such as the 1966 United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, that explicitly prohibits that anyone be subjected to scientific experimentation without their permission).

Consent is based on four prerequisites: (1) it is given voluntarily (free from coercion), (2) the participant is a legally competent actor, (3) is well informed, and (4) comprehends what is asked of them.