Decision Making: a Theoretical Review

- Regular Article

- Published: 15 November 2021

- Volume 56 , pages 609–629, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Matteo Morelli 1 ,

- Maria Casagrande ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4430-3367 2 &

- Giuseppe Forte 1 , 3

6471 Accesses

14 Citations

Explore all metrics

Decision-making is a crucial skill that has a central role in everyday life and is necessary for adaptation to the environment and autonomy. It is the ability to choose between two or more options, and it has been studied through several theoretical approaches and by different disciplines. In this overview article, we contend a theoretical review regarding most theorizing and research on decision-making. Specifically, we focused on different levels of analyses, including different theoretical approaches and neuropsychological aspects. Moreover, common methodological measures adopted to study decision-making were reported. This theoretical review emphasizes multiple levels of analysis and aims to summarize evidence regarding this fundamental human process. Although several aspects of the field are reported, more features of decision-making process remain uncertain and need to be clarified. Further experimental studies are necessary for understanding this process better and for integrating and refining the existing theories.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Ethical decision-making theory: an integrated approach.

In AI we trust? Perceptions about automated decision-making by artificial intelligence

Estimating power in (generalized) linear mixed models: An open introduction and tutorial in R

André, M., Borgquist, L., Foldevi, M., & Mölstad, S. (2002). Asking for ‘rules of thumb’: a way to discover tacit knowledge in general practice. Family Practice, 19 (6), 617–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/19.6.617

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S. W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50 (1–3), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275 (5304), 1293–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., & Damasio, A. R. (2000a). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral cortex, 10 (3), 295–307.

Bechara, A., Tranel, D., & Damasio, H. (2000b). Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain, 123 (Pt 11), 2189–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.11.2189

Bechara, A., & Damasio, A. R. (2005). The somatic marker hypothesis: a neural theory of economic decision. Games and Economic Behavior, 52, 336–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2004.06.010

Article Google Scholar

Blanchard, T. C., Strait, C. E., & Hayden, B. Y. (2015). Ramping ensemble activity in dorsal anterior cingulate neurons during persistent commitment to a decision. Journal of Neurophysiology, 114 (4), 2439–49. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00711.2015

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bohanec, M. (2009). Decision making: A computer-science and information-technology viewpoint. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems, 7 (2), 22–37

Google Scholar

Brand, M., Fujiwara, E., Borsutzky, S., Kalbe, E., Kessler, J., & Markowitsch, H. J. (2005). Decision-Making deficits of korsakoff patients in a new gambling task with explicit rules: associations with executive functions. Neuropsychology, 19 (3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.19.3.267

Broche-Pérez, Y., Jiménez, H., & Omar-Martínez, E. (2016). Neural substrates of decision-making. Neurologia, 31 (5), 319–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2015.03.001

Byrnes, J. P. (2013). The nature and development of decision-making: A self-regulation model . Psychology Press

Clark, L., & Manes, F. (2004). Social and emotional decision-making following frontal lobe injury. Neurocase, 10 (5), 398–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554790490882799

Cummings, J. L. (1995). Anatomic and behavioral aspects of frontal-subcortical circuits a. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 769 (1), 1–14

Dale, S. (2015). Heuristics and biases: The science of decision-making. Business Information Review, 32 (2), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382115592536

Damasio, A. R. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 351 (1346), 1413–20. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0125

Dewberry, C., Juanchich, M., & Narendran, S. (2013). Decision-making competence in everyday life: The roles of general cognitive styles, decision-making styles and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 55 (7), 783–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.012

Doya, K. (2008). Modulators of decision making. Nature Neuroscience, 11 (4), 410–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn2077

Dunn, B. D., Dalgleish, T., & Lawrence, A. D. (2006). The somatic marker hypothesis: a critical evaluation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30 (2), 239–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.07.001

Elliott, R., Rees, G., & Dolan, R. J. (1999). Ventromedial prefrontal cortex mediates guessing. Neuropsychologia, 37 (4), 403–411

Ernst, M., Bolla, K., Mouratidis, M., Contoreggi, C., Matochik, J. A., Kurian, V., et al. (2002). Decision-making in a risk-taking task: a PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology, 26 (5), 682–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00414-6

Ernst, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2005). Neurobiology of decision making: a selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (8), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.004

Evans, J. S. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–78. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

Fellows, L. K. (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of human decision making: A review and conceptual framework. Behavioral & Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 3 (3), 159–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582304273251

Fellows, L. K., & Farah, M. J. (2007). The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in decision making: judgment under uncertainty or judgment per se? Cerebral Cortex, 17 (11), 2669–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhl176

Fehr, E., & Camerer, C. F. (2007). Social neuroeconomics: the neural circuitry of social preferences. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11 (10), 419–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.002

Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., & Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(200001/03)13:1<1::AID-BDM333>3.0.CO;2-S

Fischhoff, B. (2010). Judgment and decision making. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1 (5), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.65

Forte, G., Favieri, F., & Casagrande, M. (2019). Heart rate variability and cognitive function: a systematic review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 710

Forte, G., Morelli, M., & Casagrande, M. (2021). Heart rate variability and decision-making: autonomic responses in making decisions. Brain Sciences, 11 (2), 243

Forte, G., Favieri, F., Oliha, E. O., Marotta, A., & Casagrande, M. (2021). Anxiety and attentional processes: the role of resting heart rate variability. Brain Sciences, 11 (4), 480

Frith, C. D., & Singer, T. (2008). The role of social cognition in decision making. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 363 (1511), 3875–86. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0156

Galotti, K. M. (2002). Making decisions that matter: How people face important life choices . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 451–82. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346

Gigerenzer, G., & Selten, R. (Eds.). (2001). Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox . MIT Press

Goel, V., Gold, B., Kapur, S., & Houle, S. (1998). Neuroanatomical correlates of human reasoning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 10 (3), 293–302

Gold, J. I., & Shadlen, M. N. (2007). The neural basis of decision making. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 30, 535–74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113038

Gottlieb, J. (2007). From thought to action: the parietal cortex as a bridge between perception, action, and cognition. Neuron, 53 (1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.009

Gozli, D. G. (2017). Behaviour versus performance: The veiled commitment of experimental psychology. Theory & Psychology, 27, 741–758

Gozli, D. (2019). Free Choice. Experimental Psychology and Human Agency . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20422-8_6

Group, T. M. A. D., Fawcett, T. W., Fallenstein, B., Higginson, A. D., Houston, A. I., Mallpress, D. E., & McNamara, J. M., …. (2014). The evolution of decision rules in complex environments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 18 (3), 153–161

Guess, C. (2004). Decision making in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture , 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1032

Gupta, R., Koscik, T. R., Bechara, A., & Tranel, D. (2011). The amygdala and decision-making. Neuropsychologia, 49 (4), 760–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.09.029

Heilbronner, S. R., & Hayden, B. Y. (2016). Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a bottom-up view. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 39, 149–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013952

Hickson, L., & Khemka, I. (2014). The psychology of decision making. International review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol 47, pp. 185–229). Academic

Johnson, J. G., & Busemeyer, J. R. (2010). Decision making under risk and uncertainty. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1 (5), 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.76

Kable, J. W., & Glimcher, P. W. (2009). The neurobiology of decision: consensus and controversy. Neuron , 63 (6),733–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.003

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice. Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist, 58 (9), 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697

Kahneman, D. (2011). P ensieri lenti e veloci . Trad.it. a cura di Serra, L., Arnoldo Mondadori Editore

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), 263–292

Kheramin, S., Body, S., Mobini, S., Ho, M. Y., Velázquez-Martinez, D. N., Bradshaw, C. M., et al. (2002). Effects of quinolinic acid-induced lesions of the orbital prefrontal cortex on inter-temporal choice: a quantitative analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 165 (1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-002-1228-6

Lee, V. K., & Harris, L. T. (2013). How social cognition can inform social decision making. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00259

Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66 , 799–823

Loewenstein, G., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127 (2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267

Mather, M. (2006). A review of decision-making processes: weighing the risks and benefits of aging. In Carstensen, L. L., & Hartel, C. R. (Eds.), & Committee on Aging Frontiers in Social Psychology, Personality, and Adult Developmental Psychology, Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences, When I’m 64 (pp. 145–173). National Academies Press

Mazzucchi, L. (2012). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica: Premesse teoriche e applicazioni cliniche (3rd ed.). EDRA

Mishra, S. (2014). Decision-making under risk: integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18 (3), 280–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314530517

Moreira, C. (2018). Unifying decision-making: a review on evolutionary theories on rationality and cognitive biases. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.12455

Naqvi, N., Shiv, B., & Bechara, A. (2006). The role of emotion in decision making: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15 (5), 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00448.x

O’Doherty, J. P., Buchanan, T. W., Seymour, B., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Predictive neural coding of reward preference involves dissociable responses in human ventral midbrain and ventral striatum. Neuron, 49 (1), 157–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.014

Padoa-Schioppa, C., & Assad, J. A. (2008). The representation of economic value in the orbitofrontal cortex is invariant for changes of menu. Nature Neuroscience, 11 (1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn2020

Palombo, D. J., Keane, M. M., & Verfaellie, M. (2015). How does the hippocampus shape decisions? Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 125, 93–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2015.08.005

Pardo-Vazquez, J. L., Padron, I., Fernandez-Rey, J., & Acuña, C. (2011). Decision-making in the ventral premotor cortex harbinger of action. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2011.00054

Paulus, M. P., & Yu, A. J. (2012). Emotion and decision-making: affect-driven belief systems in anxiety and depression. Trends in Cognitive Science, 16, 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.07.009

Payne, J. W. (1973). Alternative approaches to decision making under risk: Moments versus risk dimensions. Psychological Bulletin, 80 (6), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035260

Payne, J. W., Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker . Cambridge University Press

Phelps, E. A., Lempert, K. M., & Sokol-Hessner, P. (2014). Emotion and decision making: multiple modulatory neural circuits. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 37, 263–287

Pronin, E. (2007). Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11 (1), 37–43

Rangel, A., Camerer, C., & Read Montague, P. (2008). Neuroeconomics: The neurobiology of value-based decision-making. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9 (7), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2357

Reyna, V. F., & Lloyd, F. J. (2006). Physician decision making and cardiac risk: Effects of knowledge, risk perception, risk tolerance, and fuzzy processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 12 (3), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-898X.12.3.179

Rilling, J. K., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). The neuroscience of social decision-making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131647

Robinson, D. N. (2016). Explanation and the “brain sciences". Theory & Psychology, 26 (3), 324–332

Robbins, T. W., James, M., Owen, A. M., Sahakian, B. J., McInnes, L., & Rabbitt, P. (1994). Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): a factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia, 5 (5), 266–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000106735

Rogers, R. D., Owen, A. M., Middleton, H. C., Williams, E. J., Pickard, J. D., Sahakian, B. J., et al. (1999). Choosing between small, likely rewards and large, unlikely rewards activates inferior and orbital prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 19 (20), 9029–9038. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-09029.1999

Rolls, E. T., & Baylis, L. L. (1994). Gustatory, olfactory, and visual convergence within the primate orbitofrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 14 (9), 5437–52. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05437.1994

Rolls, E. T., Critchley, H. D., Browning, A. S., Hernadi, I., & Lenard, L. (1999). Responses to the sensory properties of fat of neurons in the primate orbitofrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 19 (4), 1532–40. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01532.1999

Rosenbloom, M. H., Schmahmann, J. D., & Price, B. H. (2012). The functional neuroanatomy of decision-making. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24 (3), 266–77. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11060139

Rushworth, M. F., & Behrens, T. E. (2008). Choice, uncertainty and value in prefrontal and cingulate cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 11 (4), 389–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn2066

Sanfey, A. G. (2007). Social decision-making: insights from game theory and neuroscience. Science, 318 (5850), 598–602. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1142996

Serra, L., Bruschini, M., Ottaviani, C., Di Domenico, C., Fadda, L., Caltagirone, C., et al. (2019). Thalamocortical disconnection affects the somatic marker and social cognition: a case report. Neurocase, 25 (1–2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2019.1599025

Shahsavarani, A. M., & Abadi, E. A. M. (2015). The bases, principles, and methods of decision-making: A review of literature. International Journal of Medical Reviews, 2 (1), 214–225

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). Rational actors or rational fools: Implications of the affect heuristic for behavioral economics. Journal of Socio-Economics, 31 (4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(02)00174-9

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24, 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x

Staerklé, C. (2015). Political Psychology. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences , 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24079-8

Tremblay, S., Sharika, K. M., & Platt, M. L. (2017). Social decision-making and the brain: a comparative perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21 (4), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.01.007

Trepel, C., Fox, C. R., & Poldrack, R. A. (2005). Prospect theory on the brain? Toward a cognitive neuroscience of decision under risk. Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research, 23 (1), 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.016

Van Der Pligt, J. (2015). Decision making, psychology of. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2 (5), 917–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24014-2

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior . Princeton University Press

Weber, E. U., & Hsee, C. K. (2000). Culture and individual judgment and decision making. Applied Psychology: An International Journal, 49, 32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00005

Weller, J. A., Levin, I. P., Shiv, B., & Bechara, A. (2009). The effects of insula damage on decision-making for risky gains and losses. Society for Neuroscience, 4 (4), 347–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470910902934400

Williams, D. J., & Noyes, J. M. (2007). How does our perception of risk influence decision-making? Implications for the design of risk information. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 8, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14639220500484419

Yamada, H., Inokawa, H., Matsumoto, N., Ueda, Y., & Kimura, M. (2011). Neuronal basis for evaluating selected action in the primate striatum. European Journal of Neuroscience, 34 (3), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07771.x

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università di Roma “Sapienza”, Via dei Marsi. 78, 00185, Rome, Italy

Matteo Morelli & Giuseppe Forte

Dipartimento di Psicologia Dinamica, Clinica e Salute, Università di Roma “Sapienza”, Via degli Apuli, 1, 00185, Rome, Italy

Maria Casagrande

Body and Action Lab, IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia, Rome, Italy

Giuseppe Forte

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Maria Casagrande or Giuseppe Forte .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Morelli, M., Casagrande, M. & Forte, G. Decision Making: a Theoretical Review. Integr. psych. behav. 56 , 609–629 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-021-09669-x

Download citation

Accepted : 09 November 2021

Published : 15 November 2021

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-021-09669-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Decision making

- Neural correlates of decision making

- Decision-making tasks

- Decision-making theories

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

OPINION article

Decision-making in health and fitness.

- 1 Independent Researcher, Ormond Beach, FL, United States

- 2 Sports Performance Research Institute New Zealand, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Introduction

Lifestyle choices associated with food and exercise habits are fundamentally a complex decision-making process associated with many biological, social, and emotional variables. As this may be considered more difficult and time consuming, many people choose to make the simple straightforward and emotional decision influenced primarily by marketers and social media, giving consumers the perception of quick, positive predictable outcomes, even if they are inaccurate and appear too good to be true. Rather than a lack of consensus by scientists and clinicians on how to improve health and fitness, poor choices by consumers encouraged by advertisements and social trends may contribute to the continued growth of chronic illness and disability that leads to higher healthcare costs. Within this framework, modern decision-making theory may help us better understand this global problem.

Marketers selling health and fitness products and services have long since seized on our tendency to respond to advertisements that promise quick-fix solutions—especially diet and exercise fads that speak to the emotionally-run limbic system and easily grab consumer attention. Unfortunately, these initiatives often prevent people from thinking about the potential benefits and risks of using such products and services, which requires a more complex decision-making cognitive process to make the same choice. Weight loss, injury prevention , and increased energy are among the common buzzwords that quickly receive consumer's attention. Terms like fresh, natural , and local , which don't necessarily imply healthy, along with many certified organic food items, can in fact be classified as junk food. These quick-fix choices often result in postponing improved health and fitness for an individual, with wide-ranging negative outcomes; consider the current overfat pandemic with its downstream diseases and disabilities in the US, where, despite rising exercise rates, 91% of adults are now affected ( 1 , 2 ).

Since food and exercise are known to significantly influence health and fitness, and impact the development of chronic disease, disability, and premature death ( 3 ), the processes by which individuals make lifestyle choices—and their related consequences—should be an important public health concern.

Cognitive Decision-Making

Denes-Raj and Epstein ( 4 ) suggest that decision-making behavior is guided by two different cognitive processes, the first being an emotional response typical of interpersonal interactions, and the second an analytical response such as that used to solve a mathematical problem. The theory was simplified further by Amos Tversky, with Stanovich and West naming the emotional process “System 1” and the rational one “System 2” ( 5 , 6 ). Kahneman applied these ideas to economic behavior ( 7 ), with Tversky and Kahneman awarded separate Nobel prizes for their respective works. The application of System 1 and System 2 decision-making behavior in the context of health and fitness can have wide-ranging potential personal and global public health implications, and is described here as behavioral health and fitness . [ Health is defined as all areas of the body working in harmony, while fitness is the ability to perform physical activity ( 8 )].

Large numbers of people around the world attempt to regularly manage a variety of personal health and fitness routines. At its onset, this self-care process can be strongly influenced by companies selling products and services (diets, books, programs, exercise equipment) through radio and TV, online and print media, health, and fitness societies/agencies and from governmental recommendations, the latter two strongly influenced by politics and lobbying. The process is often void of individuality, encourages a one-size-fits-all notion, and can lead to dangerous herd behavior ( 9 ). These are associated with a System 1 response. Personalizing food and exercise choices require more thinking and is associated with System 2.

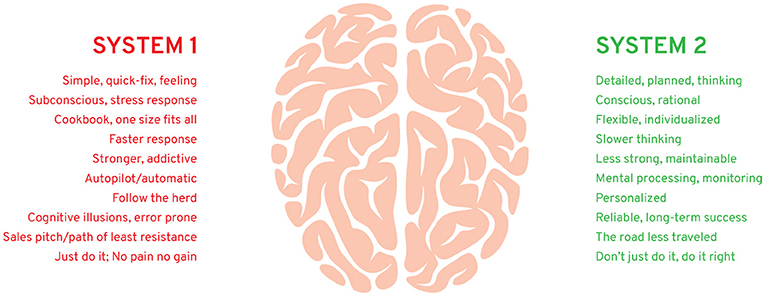

Characteristics of System 1 and System 2

Normally, both modes of decision-making are used in our day-to-day lives, and both have potential value. Consider System 1's first impression, an often accurate assessment of another person, place, food and physical activity. This impression may correspond to one's System 2 analysis over time. However, more often the use of images, words, sounds and other impressions in marketing, quickly sway people by enlisting System 1 to help sell unhealthy products and services.

Involving simple everyday choices that are habit- and reaction-based, usually made with little thinking, attention, or information, System 1 governs the quick decisions such as which of several doors to use when entering an office building, lanes to take on a highway, or seats to sit in at an airport. However, important decisions that can impact on immediate and long-term individual and population health and fitness are influenced if not governed by System 1 as well ( 10 ).

The System 1 process is primarily an unconscious but natural reaction, such that one's true underlying attitude or motivation for the decision is hard to come by, and the individual will likely provide one of several plausible rationalizations to justify how they made the decision. While this system is leveraged particularly well by marketers advertising products and services, it comes with the potential for strong bias and error referred to as cognitive illusions that can lead to reduced health and fitness. Fleeting first impressions appear attractive to System 1 and predominate its decision-making: Seeing a splashy colorful cover of a new diet book or a smiling lean person working out are common examples.

Relying on conscious intellect for lifestyle decision-making, System 2 requires more time to assess a particular eating plan or exercise program. In terms of self-care, it also provides an individual with the ability for ongoing monitoring of signs and symptoms that measure progress.

The more reliable and logical System 2 process can yield a personalized approach rather than a one-size-fits-all menu, and grants the ability to incorporate a planned, flexible program that can lead to improved outcomes ( 11 ). Requiring reasonable literacy, this approach offers greater autonomy, and can also reduce healthcare costs ( 12 ).

Figure 1 lists some factors associated with System 1 and System 2 decision-making.

Figure 1 . Some factors associated with behavioral health and fitness.

Health practitioners can also play an important part in teaching patients about the lifestyle habits associated with their particular needs, helping them avoid making irrational or poor choices ( 3 , 13 ). However, for the benefits of health education to succeed, a high level of engagement is required. Here again, this may be impaired by society's System 1 dominance in the health and fitness arena, where consumers—patients and practitioners alike—are influenced. Unfortunately, few practitioners provide details on decision-making and modification of behavior for other related reasons: it's time-consuming, most practitioners are not knowledgeable enough, and patients are given few strategies for maintenance. Likewise, governmental recommendations are extremely simplistic, not individualized, and without encouragement.

Costs of System 1

System 1 marketing deception has been a successful business strategy for decades, selling untold numbers of health and fitness products and services that promise quick improvement that System 2 thinks is unlikely. For example, the diet industry in Europe and the United States alone has annual revenues in excess of $150 billion, and rising, yet up to two-thirds of any weight lost is regained within 1 year—and almost all is regained within 5 years, along with lost health ( 14 ).

Downstream healthcare costs continue to be high and are rising globally as well. In the US, 2014 health-care costs climbed to $3.2 trillion ( 15 ), with the Kaiser Family Foundation estimating a worldwide cumulative healthcare loss of $47 trillion between 2011 and 2030.

Examples and Misconceptions

Here, we provide two examples of how the reliance of a System 1 approach can lead to failure:

1. A person wanting to lose weight is attracted to a program claiming you can shed 10 pounds the first week. Whether initially successful or not, the diet usually fails to provide long-term results, and may cause side effects such as nutritional imbalance, metabolic impairment, and disordered eating.

2. A person wants to exercise to get into shape. Regular gym workouts encouraged by the no pain, no gain philosophy pushes the process. After a period of initial excitement, with some results realized—lost weight, more fitness—fatigue, soreness, injury, and frustration may develop causing some to give up working out. Others may become addicted to exercise, and despite pain or frustration, continue pushing through it, increasing stress hormones that impair health and fitness.

System 1-based marketing has spawned many popular misconceptions, trendy fads, and rally cries that become unhealthy social mantras. Below are two popular and very successful examples:

1. No pain, no gain . Perhaps the first social description of no-pain no-gain came from Benjamin Franklin in his writings on capitalism ( 16 ). But in the fitness arena, this rallying cry glorifies pain and the high rates of preventable injury. It overshadows the scientific consensus (System 2), considered more effective and healthy. Bill Bowerman, legendary sports coach and co-founder of Nike, said, “The idea that the harder you work, the better you're going to be is just garbage. The greatest improvement is made by the man or woman who works most intelligently.”

2. Just do it . Ironically, this popular Nike ad slogan, which appeared later in the company's evolution, communicates the System 1 message that it is enough to simply make a snap judgment to follow a certain exercise ritual without further consideration, encouraging a herd mentality ( 9 ). System 2 might think, don't just do it, do it right .

The New Players

Mobile trackers are the relatively new players in the health and fitness arena, and enlist primarily System 1 due to their emphasis on gaming and gamification. As they collect largely irrelevant data, users tend to give up on them within 6 months ( 17 ). Despite this, analysts at Morgan Stanley believe these devices will become a $1.6 trillion business in the near future ( 18 ). Indeed, the System 1 slant of mobile trackers, in the absence of more substantive and sophisticated analytics that engage System 2 thinking, may contribute to their early abandonment and demise: there is little reason to continue engaging the user through System 2 once System 1 thinking has run its course, at which point the user moves on to the next new device or program that captures the attention of System 1.

A Public Health Choice

The purpose of public health includes informing and educating the public, mobilizing community partnerships, developing policies to support health goals, and enforcing related laws and regulations ( 19 ). Despite the reality that many consumers use System 1 thinking to make unhealthy lifestyle choices, public health officials, health practitioners, policy makers, and others must work out how best to interact with an existing System 1 process to reverse this trend ( 13 , 20 ). Exploiting System 1 can help make health and fitness habitual, a process accomplished many times with whole populations reducing health-related risks through public health actions. Wide et al. ( 21 ) showed that a brief psychological intervention in young adults with a high prevalence of dental caries led to an immediate positive effect with improved oral health behaviors. The use of seatbelts has significantly reduced injury and death in vehicular accidents due to laws, high visibility enforcement, and fines, and promoting positive beliefs ( 22 ). The importance of hand washing education to help prevent infections has occurred throughout most populations ( 23 ). Promotion of self-care has also been effective in such areas as breast cancer screening behavior ( 24 ), and gestational anemia ( 25 ). While we applaud these and other public health successes, improved behavioral health and fitness promotions are urgently needed, while reducing the advertisement of unhealthy products and services to avoid drowning out the positive recommendations.

Recommendations

More specific suggestions to encourage individuals to avoid making poor diet and exercise choices can be made through two general public health approaches. First is to further restrict or ban the advertising and promotion of unhealthy products and services. This is being achieved with tobacco, and is gradually being implemented now by a ban on soda sales in some schools or junk food in some hospitals, and/or through a higher tax on unhealthy products. Second, and concurrent, is the promotion of healthy options, which can also include reductions or elimination of tax on healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables. These can be attempted through System 2 approaches but simplified sufficiently for most people to understand, implement, and maintain. This strategy may also require more creative, simple System 1-type guidelines, not unlike traditional successful marketing, to encourage easier understanding and behavioral changes. In addition:

- Public health communication messages and campaigns should be more clear and modernized; the Institute of Medicine found a major mismatch between the health information people receive and what they understand ( 26 ).

- These lifestyle recommendations should also be updated regularly as they can quickly become outdated ( 27 ). For example, the US government has just updated recommendations for physical activity for the first time in 10 years; compared with this once a decade frequency, companies promoting unhealthy products and services are bombarding consumers on a daily basis ( 28 ).

- The promotion of education strategies has already been successfully applied to individuals performing self-care for such conditions as cardiovascular disease ( 29 ) and mild cognitive impairment ( 30 ). With a sufficient level of scientific consensus in the area of diet and exercise, similar strategies regularly implemented can help people make better choices and offset ongoing System 1 misinformation campaigns.

There is no doubt that lifestyle change is difficult, one created in great part by decades of harmful System 1 marketing. This also can feed poor self-discipline in consumers. However, with the added awareness of behavioral health and fitness, combined with the help of public health actions, the process of self-care that many consumers follow could improve discipline and intellectual judgment as part of a System 2 process that more likely brings long-term success.

When it comes to making lifestyle choices, large numbers of people around the world who practice self-care are guided by System 1 thinking primarily from corporate marketing of health and fitness products and services that have potentially grave, unhealthy consequences. This may be significantly influencing the corresponding rise of chronic disease, physical impairment, lowered mental health, reduced quality of life, and healthcare costs. It is our hope that this article could help further increase public health awareness and stimulate a more detailed plan of action for effective strategies to improve and maintain health and fitness behavior, and consequently reduce mortality and morbidity of chronic disease and disability in adults and children.

Author Contributions

PM conceived the idea for the manuscript and lead the authorship process. PL edited a draft of the manuscript and contributed to the content.

Conflict of Interest Statement

PM is an independent clinical consultant, writes articles, and books that include the topics presented herein, and has a business website pertaining to health and fitness ( www.philmaffetone.com ). PL is an independent consultant, writes articles and books, and has a website pertaining to performance, health, and longevity ( www.plewsandprof.com ).

1. Maffetone PB, Rivera-Dominguez I, Laursen PB. Overfat and underfat: new terms and definitions long overdue. Front Public Health (2016) 4:279. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00279

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Maffetone PB, Laursen PB. The prevalence of overfat adults and children in the US. Front Public Health (2017) 5:290. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00290

3. Adams RJ. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy (2010) 3:61–72. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S7500

4. Denes-Raj V, Epstein S. Conflict between intuitive and rational processing: when people behave against their better judgment. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1994) 66:819–29. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.819

5. Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. In: Kahneman D, Slovic P, Tversky A, editors. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (1982).

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

6. Stanovich KE, West RF. Individual differences in reasoning: implications for the rationality debate? Behav Brain Sci. (2000) 23:645–65; discussion 665–726. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00003435

7. Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am Psychol. (2003) 58:697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697

8. Maffetone PB, Laursen PB. Athletes: fit but unhealthy? Sports Med Open (2015) 2:24. doi: 10.1186/s40798-016-0048-x

9. Banerjee AV. A simple model of herd behavior. Q J Econ. (1992) 107:797–817. doi: 10.2307/2118364

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin (2011).

Google Scholar

11. Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, et al. Meta-analysis: chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Ann Intern Med. (2005) 143:427–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00007

12. Anderson K, Burford O, Emmerton L. Mobile health apps to facilitate self-care: a qualitative study of user experiences. PLoS ONE (2016) 11:e0156164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156164

13. Polak L. Making health habitual. Br J Gen Pract. (2013) 63:70–1. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X662966

14. Dulloo AG, Montani JP. Pathways from dieting to weight regain, to obesity and to the metabolic syndrome: an overview. Obes Rev. (2015) 16(Suppl. 1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/obr.12250

15. Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, Catlin A National Health Expenditure Accounts T. National health spending in 2014: faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff. (2016) 35:150–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1194

16. Reinert SA. The way to wealth around the world: Benjamin Franklin and the Globalization of American Capitalism. Am Hist Rev . (2015) 120:61–97. doi: 10.1093/ahr/120.1.61

17. Michael A. Major Trends in the Wearable Devices Industry [Online] (2016). Available online at: http://www.wearabledevices.com/2016/01/05/major-trends-in-the-wearable-devices-industry/ (Accessed Oct 18, 2018).

18. Danova T. Just 3.3 Million Fitness Trackers Were Sold in the US in the Past Year [Online] . Business Insider (2014). Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com/33-million-fitness-trackers-were-sold-in-the-us-in-the-past-year-2014-5 (Accessed Oct 18, 2018).

19. Stover GN, Bassett MT. Practice is the purpose of public health. Am J Public Health (2003) 93:1799–801. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.11.1799

20. Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation' and general practice. Br J Gen Pract. (2012) 62:664–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X659466

21. Wide U, Hagman J, Werner H, Hakeberg M. Can a brief psychological intervention improve oral health behaviour? A randomised controlled trial. BMC Oral Health (2018) 18:163. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0627-y

22. Buckley L, Jones MLH, Ebert SM, Reed MP, Hallman JJ. Evaluating an intervention to improve belt fit for adult occupants: promoting positive beliefs. J Safety Res. (2018) 64:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2017.12.012

23. Ataee RA, Ataee MH, Mehrabi Tavana A, Salesi M. Bacteriological aspects of hand washing: a key for health promotion and infections control. Int J Prev Med. (2017) 8:16. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.201923

24. Saei Ghare Naz M, Simbar M, Rashidi Fakari F, Ghasemi V. Effects of model-based interventions on breast cancer screening behavior of women: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2018) 19:2031–41. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.8.2031

25. Seshan V, Alkhasawneh E, Al Kindi S, Al Simadi FA, Arulappan J. Can gestational anemia be alleviated with increased awareness of its causes and management strategies? implications for health care services. Oman Med J. (2018) 33:322–30. doi: 10.5001/omj.2018.59

26. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2004).

27. Martinez Garcia L, Sanabria AJ, Garcia Alvarez E, Trujillo-Martin MM, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Kotzeva A, et al. The validity of recommendations from clinical guidelines: a survival analysis. CMAJ (2014) 186:1211–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140547

28. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (Online). President's Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Available online at: https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans/index.html (Accessed Nov 16, 2018).

29. Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, Dickson VV, Dunbar SB, Lee CS, et al. Self-care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6:e006997. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006997

30. Vanoh D, Ishak IH, Shahar S, Manaf ZA, Ali NM, Noah SM. Development and assessment of a web-based intervention for educating older people on strategies promoting healthy cognition. Clin Interv Aging (2018) 13:1787–98. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S157324

Keywords: chronic disease, consumer choice behavior, emotion reactivity, system 1 and system 2, health education, diet, exercise

Citation: Maffetone PB and Laursen PB (2019) Decision-Making in Health and Fitness. Front. Public Health 7:6. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00006

Received: 25 October 2018; Accepted: 08 January 2019; Published: 23 January 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Maffetone and Laursen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philip B. Maffetone, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2022

A framework of evidence-based decision-making in health system management: a best-fit framework synthesis

- Tahereh Shafaghat 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Peivand Bastani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0412-0267 1 , 3 na1 ,

- Mohammad Hasan Imani Nasab 4 ,

- Mohammad Amin Bahrami 1 ,

- Mahsa Roozrokh Arshadi Montazer 5 ,

- Mohammad Kazem Rahimi Zarchi 2 &

- Sisira Edirippulige 6

Archives of Public Health volume 80 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

7 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scientific evidence is the basis for improving public health; decision-making without sufficient attention to evidence may lead to unpleasant consequences. Despite efforts to create comprehensive guidelines and models for evidence-based decision-making (EBDM), there isn`t any to make the best decisions concerning scarce resources and unlimited needs . The present study aimed to develop a comprehensive applied framework for EBDM.

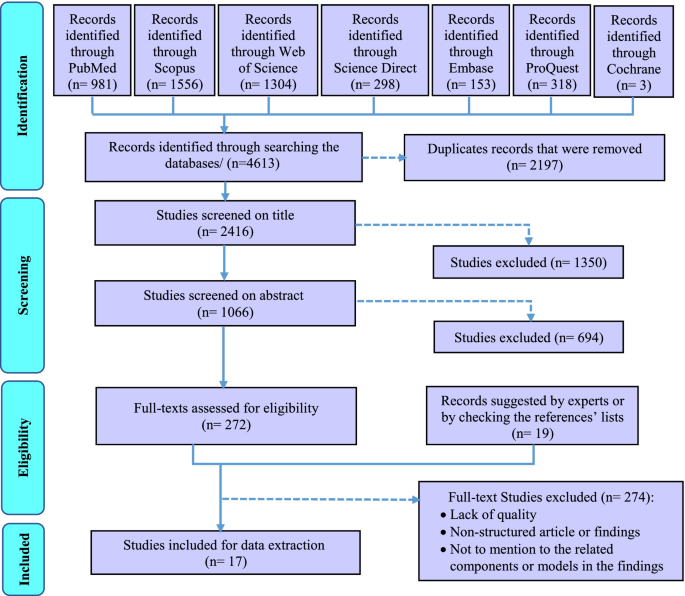

This was a Best-Fit Framework (BFF) synthesis conducted in 2020. A comprehensive systematic review was done via six main databases including PUBMED, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, EMBASE, and ProQuest using related keywords. After the evidence quality appraisal, data were extracted and analyzed via thematic analysis. Results of the thematic analysis and the concepts generated by the research team were then synthesized to achieve the best-fit framework applying Carroll et al. (2013) approach.

Four thousand six hundred thirteen studies were retrieved, and due to the full-text screening of the studies, 17 final articles were selected for extracting the components and steps of EBDM in Health System Management (HSM). After collecting, synthesizing, and categorizing key information, the framework of EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general scopes. These comprised inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating, which included 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps.

Conclusions

The present framework provided a comprehensive guideline that can be well adapted for implementing EBDM in health systems and related organizations especially in underdeveloped and developing countries where there is usually a lag in updating and applying evidence in their decision-making process. In addition, this framework by providing a complete, well-detailed, and the sequential process can be tested in the organizational decision-making process by developed countries to improve their EBDM cycle.

Peer Review reports

Globally, there is a growing interest in using the research evidence in public health policy-making [ 1 , 2 ]. Public health systems are diverse and complex, and health policymakers face many challenges in developing and implementing policies and programs that are required to be efficient [ 1 , 3 ]. The use of scientific evidence is considered to be an effective approach in the decision-making process [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Due to the lack of sufficient resources, evidence-based decision-making ( EBDM) is regarded as a way to optimize costs and prevent wastes [ 6 ]. At the same time, the direct consequence of ignoring evidence is poorer health for the community [ 7 ].

Evidence suggests that health systems often fail to exploit research evidence properly, leading to inefficiencies, death or reduced quality of citizens’ lives, and a decline in productivity [ 8 ]. Decision-making in the health sector without sufficient attention to evidence may lead to a lack of effectiveness, efficiency, and fairness in health systems [ 9 ]. Instead, the advantages of EBDM include adopting cost-effective interventions, making optimal use of limited resources, increasing customer satisfaction, minimizing harm to individuals and society, achieving better health outcomes for individuals and society [ 10 , 11 ], as well as increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of public health programs [ 12 ].

Using the evidence in health systems’ policymaking is a considerable challenging issue that many developed and developing countries are facing nowadays. This is particularly important in the latter, where their health systems are in a rapid transition [ 13 ]. For instance, although in 2012, a study in European Union countries showed that health policymakers rarely had necessary structures, processes, and tools to exploit research evidence in the policy cycle [ 14 ], the condition can be worse among the developing and the underdeveloped ones. For example, evidence-based policy-making in developing countries like those located in the Middle East can have more significant impacts [ 15 , 16 ]. In such countries resources are generally scarce, so the policymakers' awareness of research evidence becomes more important [ 17 ]. In general, low and middle-income countries have fewer resources to deal with health issues and need quality evidence for efficient use of these resources [ 7 ].

Since the use of EBDM is fraught with the dilemma of most pressing needs and having the least capacity for implementation especially in developing countries [ 16 ], efforts have been made to create more comprehensive guidelines for EBDM in healthcare settings, in recent years [ 18 ]. Stakeholders are significantly interested in supporting evidence-based projects that can quickly prioritize funding allocated to health sectors to ensure the effective use of their financial resources [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. However, it is unlikely that the implementation of EBDM in Health System Management (HSM) will follow the evidence-based medicine model [ 10 , 22 ]. On the other hand, the capacity of organizations to facilitate evidence utilization is complex and not well understood [ 22 ], and the EBDM process is not usually institutionalized within the organizational processes [ 10 ]. A study in 2005 found that few organizations support the use of research evidence in health-related decisions, globally [ 23 ]. Weis et al. (2012) also reported there is insufficient information on EBDM in local health sectors [ 12 ]. In general, it can be emphasized that relatively few organizations hold themselves accountable for using research evidence in developing health policies [ 24 ]. To the best of our knowledge, there isn`t any comprehensive global and practical model developed for EBDM in health systems/organizations management. Accordingly, the present study aimed to develop a comprehensive framework for EBDM in health system management. It can shed the light on policymakers to access a detailed practical model and enable them to apply the model in actual conditions.

This was a Best Fit Framework (BFF) synthesis conducted in 2020 to develop a comprehensive framework for EBDM in HSM. Such a framework synthesis is achieved as a combination of the relevant framework, theory, or conceptual models and particularly is applied for developing a priori framework based on deductive reasoning [ 25 ]. The BFF approach is appropriate to create conceptual models to describe or express the decisions and behaviors of individuals and groups in a particular domain. This is distinct from other methods of evidence synthesis because it employs a systematic approach to create an initial framework for synthesis based on existing frameworks, models, or theories [ 25 ] for identifying and adapting theories systematically with the rapid synthesis of evidence [ 25 , 26 ]. The initial framework can be derived from a relatively well-known model in the target field, or be formed by the integration of several existing models. The initial framework is then reduced to its key components that have shaped its concepts [ 25 ]. Indeed, the initial framework considers as the basis and it can be rebuilt, extended, or reduced based on its dimensions [ 26 ]. New concepts also emerge based on the researchers' interpretation of the evidence and ongoing comparisons of these concepts across studies [ 25 ]. This approach of synthesis possesses both positivist and interpretative perspectives; it provides the simultaneous use of the well-known strengths of both framework and evidence synthesis [ 27 ].

In order to achieve this aim the following methodological steps were conducted as follows:

Searching and selection of studies

In this step, we aimed to look for the relevant models and frameworks related to evidence-based decision-making in health systems management. The main research question was “what is the best framework for EBDM in health systems?” after defining the research question, the researchers searched for published studies on EBDM in HSM in different scientific databases with relevant keywords and constraints as inclusion and exclusion criteria from 01.01.2000 to 12.31.2020 (Table 1 ).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were determined as the studies that identify the components or develop a model or framework of EBDM in health organization in the form of original or review articles or dissertations, which were published in English and had a full text. The studies like book reviews, opinion articles, and commentaries that lacked a specific framework for conducting our review were excluded. During the search phase of the study, we attempted as much as possible to access studies that were not included in the search process or gray literature by reviewing the references lists of the retrieved studies or by contacting the authors of the articles or experts and querying them, as well as manually searching the related sites (Fig. 1 ).

The PRISMA flowchart for selection of the studies in scoping review

Quality appraisal

The quality of the obtained studies was investigated using three tools for assessing the quality of various types of studies considering types and methods of the final include studies in systematic review. These tools were including Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) for assessing the quality of qualitative researches [ 28 ], Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA) [ 29 ], and The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers [ 30 ] (Table 3- Appendix ).

Data extraction

After searching the studies from all databases and removing duplicates, the studies were independently reviewed and screened by two members (TS and MRAM) of the research team in three phases by the title, abstract, and then the full text of the articles. At each stage of the study, the final decision to enter the study to the next stage was based on agreement and, in case of disagreement, the opinion of the third person from the research team was asked (PB). Mendeley reference manager software was used to systematically search and screen relevant studies. The data from the included studies were extracted based on the study questions and accordingly, a form of the studies’ profile including the author's name, publication year, country, study title, type of study, and its conditions were prepared in Microsoft Excel software (Table 4- Appendix ).

Synthesis and the conceptual model

In this step, a thematic analysis approach was applied to extract and analyze the data. For this purpose, first, the texts of the selected studies were read several times, and the initial qualitative codes or thematic concepts, according to the determined keywords and based on the research question, were found and labeled. Then these initial thematic codes were reviewed to achieve the final codes and they were integrated and categorized to achieve the final main themes and sub-themes, eventually. The main and the sub-themes are representative of the main and sub-steps of EBDM. At the last stage of the synthesis, the thematic analysis was finalized with 8 main themes and all the main and the sub-themes were tabulated (Table 5- Appendix ).

Creation of a new conceptual framework

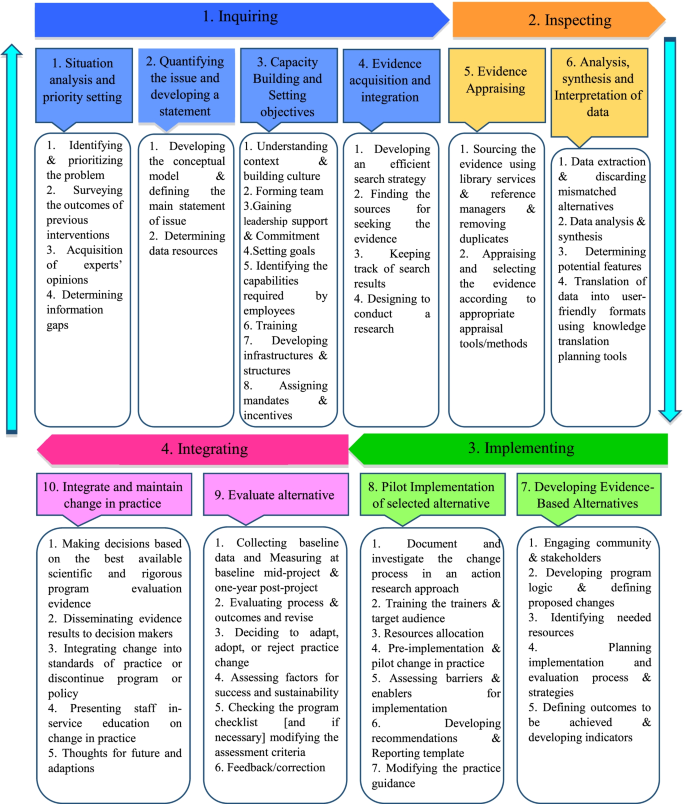

For BFF synthesis in the present study, we compared the existing models and tried to find a model that fits the best. Three related models that appeared to be relatively well-suited to the purpose of this study to provide a complete, comprehensive, and practical EBDM model in HSM were found. According to the BFF instruction in Carroll et al. (2013) study [ 25 ], we decided to use all three models as the basis for the best fit because any of those models were not complete enough and we could give no one an advantage over others. Consequently, the initial model or the BFF basis was formed and the related thematic codes were classified according to the category of this basis as the main themes/steps of EBDM in HSM (Table 5- Appendix ). Then, the additional founded thematic codes were added and incorporated to this basis as the other main steps and the sub-steps of the EBDM in HSM according to the research team and some details in the form of sub-steps were added by the research team to complete the synthesized framework. Eventually, a comprehensive practical framework consisting of 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps was created with the potentiality of applying and implementing EDBM in HSM that we categorized them into four main phases (Table 6- Appendix ).

Testing the synthesis: comparison with the a priori models, dissonance and sensitivity

In order to assess the differences between the priori framework and the new conceptual framework, the authors tried to ask some experts’ opinions about the validity of the synthesized results. The group of experts has included eight specialists in the field of health system management or health policy-making. These experts have been chosen considering their previous research or experience in evidence-based decision/policy making performance/management (Table 2 ). This panel lasted in two three-hour sessions. The finalized themes and sub-themes (Table 6- Appendix ) and the new generated framework (Fig. 3 ) were provided to them before each session so that they could think and then in each meeting they discussed them. Finally, all the synthesized themes and sub-themes resulted were reviewed and confirmed by the experts.

Ethical considerations

To prevent bias, two individuals carried out all stages of the study such as screening, data extraction, and data analysis. The overall research project related to this manuscript was approved by the medical ethics conceal of the research deputy of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences with approval number IR.SUMS.REC.1396–01-07–14184, too.

The initial search across six electronic databases and the Cochrane library yielded 4613 studies. After removing duplicates, 2416 studies were assessed based on their titles. According to the abstract screening of the 1066 studies that remained after removing the irrelevant titles, 291 studies were selected and were entered into the full-text screening phase. Due to full-text screening of the studies, 17 final studies were selected for extracting the components and steps of EBDM in HSM (Fig. 1 ). The features of these studies were summarized in Table 4- Appendix (see supplementary data). Furthermore, according to the quality appraisal of the included studies, the majority of them had an acceptable level of quality. These results have been shown in Table 3- Appendix .

Results of the thematic analysis of the evidence (Table 5- Appendix ) along with the concepts proposed and added by the research team according to the focus-group discussion of the experts were shown in Table 6- Appendix . Accordingly, the main steps and related sub-steps of the EBDM process in HSM were defined and categorized.

After collecting, synthesizing, and categorizing thematic concepts, incorporating them with the initial models, and adding the additional main steps and sub-steps to the basic models, the final synthesized framework as a best-fit framework for EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general phases of inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating and 10 main steps (Fig. 2 ). For better illustration, this framework with all the main steps and 47 sub-steps has been shown in Fig. 3 , completely.

The final synthesized framework of evidence-based decision-making in health system management

The main steps and sub-steps of the framework of EBDM in health system management

In the present study, a comprehensive framework for EBDM in HSM was developed. This model has different distinguishing characteristics than the formers. First of all, this is a comprehensive practical model that combined the strengths and the crucial components of the limited number of previous models; second, the model includes more details and complementary steps and sub-steps for full implementation of EBDM in health organizations and finally, the model is benefitted from a cyclic nature that has a priority than the linear models. Concerning the differences between the present framework and other previous models in this field, it must be said that most of the previous models related to EBDM were presented in the scope of medicine (that they were excluded from our SR according to the study objectives and exclusion criteria). A significant number of those models were proposed for the scope of public health and evidence-based practice, and only a limited number of them focused exactly on the scope of management and policy/decision making in health system organizations.

Given that the designed model is a comprehensive 10-step model, it can be used in some way at all levels of the health system and even in different countries. However, there will be a difference here, given that this framework provides a practical guide and a comprehensive guideline for applying evidence-based decision-making approach in health systems organizations, at each level of the health system in each country, this management approach can be applied depending on their existing infrastructure and the processes that are already underway (such as capacity building, planning, data collection, etc.), and at the same time, with a general guide, they can provide other infrastructure as well as the prerequisites and processes needed to make this approach much more possible and applicable.

It is true that evidence-based management is different from evidence-based medicine and even more challenging (due to lack of relevant data, greater sensitivity in data collection and their accuracy, lack of consistency and lack of transparency in the implementation of evidence-based decision-making in management rather than evidence-based medicine, etc.). Still, the general framework provided in this article can be used to help organizations that really want to act and move forward through this approach.

Furthermore, based on the findings, most of the previous studies only referred to some parts of the components and steps of the EBDM in health organizations and neglected the other parts or they were not sufficiently comprehensive [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Most of the previous models did not mention the necessary sub-steps, tools, and practical details for accurate and complete implementation of the EBDM, which causes the organizations that want to use these models, will be confused and cannot fully implement and complete the EBDM cycle. Among the studies that have provided a partly complete model than the other studies, were the studies by Brownson (2009), Yost (2014), and Janati (2018) [ 3 , 41 , 42 ]. Consequently, the combination of these three studies has been used as the initial framework for the best-fit synthesis in the present study.

Likewise, the models presented by Brownson (2009) and Janati (2018) were only limited to the six or seven key steps of the EBDM process, and they did not mention the details required for doing in each step, too [ 3 , 4 , 42 ]. Also, the model presented in the study of Janati (2018) was linear, and the relationships between the EBDM components were not well considered [ 42 , 43 ]; however, the model presented in this study was recursive. Also, in Yost's study (2014), despite the 7 main steps of EBDM and some details of each of the steps, the proposed process was not schematically drawn in the form of a framework and therefore the relationships between steps and sub-steps were not clear [ 41 ]. According to what was discussed, the best-fit framework makes the possibility of concentrating the fragmented models to a comprehensive one that can be fully applied and evaluated by the health systems policymakers and managers.

In the present study, the framework of EBDM in HSM was developed in the form of four general scopes of inquiring, inspecting, implementing, and integrating including 10 main steps and 47 sub-steps. These scopes were discussed as follows:

In the first step, “situation analysis and priority setting”, the most frequently cited sub-step was identifying and prioritizing the problem. Accordingly, Falzer (2009), emphasized the importance of identifying the decision-making conditions and the relevant institutions and determining their dependencies as the first steps of EBDM [ 44 ]. Aas (2012) has also cited the assessment of individuals and problem status and problem-finding as the first steps of EBDM [ 34 ]. Moreover, the necessity of identifying the existing situation and issues and prioritizing them has been emphasized as the initial steps in most management models such as environmental analysis in strategic planning [ 45 ].

Despite considering the opinions and experience of experts and managers as one of the important sources of evidence for decision-making [ 42 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ], many studies did not mention this sub-step in the EBDM framework. Hence, the present authors added the acquisition of experts’ opinions as a sub-step of the first step because of its important role in achieving a comprehensive view of the overall situation.

In the second step, “quantifying the issue and developing a statement”, “Developing the conceptual model for the issue” was more addressed [ 37 , 41 , 47 ]. In addition, the authors to complete this step added the fourth sub-step, “Defining the main statement of issue”. This is because that most of the problems in health settings may have a similar value for managers and decision-makers and quantifying them can be used as a criterion for more attention or selecting the problem as the main issue to solve.

The third step, “Capacity building and setting objectives”, was not seen in many other included studies as a main step in EBDM, however, the present authors include this as a main step because without considering the appropriate objectives and preparing necessary capacities and infrastructures, entering to the next steps may become problematic. Moreover, in numerous studies, factors such as knowledge and skills of human resources, training, and the availability of the essential structures and infrastructures have been identified as facilitators of EBDM [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ]. According to this justification, they are included in the present framework as sub-steps of the third step.

Considering the third step and based on the knowledge extracted from the previous studies, the three sub-steps of “understanding context and Building Culture” [ 56 , 57 ], “gaining the support and commitment of leaders” [ 39 , 57 , 58 ], and “identifying the capabilities required by employees and their skills weaknesses” [ 58 , 59 , 60 ] were the most important sub-steps in this step of EBDM framework. In this regard, Dobrow (2004) has also stated that the two essential components of any EBDM are the evidence and context of its use [ 32 ]. Furthermore, Isfeedvajani (2018) stated that to overcome barriers and persuade hospital managers and committees to apply evidence-based management and decision-making, first and foremost, creating and promoting a culture of "learning through research" was important [ 61 ].

The present findings showed that in the fourth main step, “evidence acquisition and integration”, the most important sub-step was “finding the sources for seeking the evidence” [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 60 , 62 , 63 ]. Concerning the sources for the use of evidence in decision-making in HSM, studies have cited numerous sources, most notably scientific and specialized evidence such as research, articles, academic reports, published texts, books, and clinical guidelines [ 39 , 64 , 65 ]. After scientific evidence, using the opinions and experiences of experts, colleagues, and managers [ 42 , 46 , 49 , 66 ] as well as the use of census and local level data [ 49 , 66 , 67 ], and other sources such as financial [ 67 ], political [ 42 , 49 ] and evaluations [ 49 , 68 ] data were cited.

The fifth step of the present framework, “evidence appraising”, was emphasized by previous literature; for instance, Pierson (2012) pointed to the use of library services in EBDM [ 69 ]. Appraising and selecting the evidence according to appropriate appraisal tools/methods was cited the most. International and local evidence is confirmed that ignoring these criteria can lead to serious faults in the process of decision and policy-making [ 70 , 71 ].

Furthermore, the sixth step, “analysis, synthesis, and interpretation of data”, was mentioned in many included studies [ 36 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 57 , 59 , 72 ]. This step emphasized the role of analysis and synthesis of data in the process of generation applied and useful information. It is obvious that the local interpretation according to different contexts may lead to achieving such kind of knowledge that can be used as a basis for local EBDM in HSM.

Implementing

The third scope consisted of the seventh and eighth steps of the EBDM process in HSM. In the seventh step, “developing evidence-based alternatives”, the issue of involving stakeholders in decision-making and subsequently, planning to design and implementation of the process and evaluation strategies had been focused by the previous studies [ 58 , 60 , 62 , 63 , 73 ]. Studies by Belay (2009) and Armstrong (2014) had also emphasized the need to use stakeholder and public opinion as well as local and demographic data in decision-making [ 49 , 67 ].

“Pilot-implementation of selected alternatives” was the eighth step of the framework. Some key sub-steps of this step were resources allocation [ 58 ], Pre-implementation and pilot change in practice and assessing barriers and enablers for implementation [ 40 ] that indicated the significance of testing the strategies in a pilot stage as a pre- requisition of implementing the whole alternatives. It is obvious that without attention to the pilot stage, adverse and unpleasant outcomes may occur that their correction process imposes many financial, organizational, and human costs on the originations. In addition, a study explained that one of the strategies of the decision-makers to measure the feasibility of the policy options was piloting them, which had a higher chance of being approved by the policymakers. Also, pilot implementation in smaller scales has been recommended in public health in cases of lack of sufficient evidence [ 74 ].

Integrating

This last scope consists of the ninth and tenth steps. The main sub-step of the ninth step, “evaluating alternatives”, was to evaluating process and outcomes and revise. After a successful implementation of the pilot, this step can be assured that the probable outcomes may be achieved and this evaluation will help the decision and policymakers to control the outcomes, effectively. Also, it impacts the whole target program and proposes some correcting plans through an accurate feedback process, too. Pagoto (2007) explained that a facilitator for EBDM would be an efficient and user-friendly system to assess utilization, outcomes, and perceived benefits [ 55 ].

Also, the tenth step, “integrating and maintaining change in practice”, was not considered as a major step in previous models, too, while it is important to maintain and sustain positive changes in organizational performance. In this regard, Ward (2011) also suggested several steps to maintain and sustain the widespread changes in the organization, including increasing the urgency and speed of action, forming a team, getting the right vision, negotiating for buy-in, empowerment, short-term success, not giving up and help to make a change stick [ 35 ]. Finally, the most important sub-steps that could be mentioned in this step were the dissemination of evidence results to decision-makers and the integration of changes made to existing standards and performance guidelines. Liang (2012) had also emphasized the importance of translating existing evidence into useful practices as well as disseminating them [ 47 ]. In addition, the final sub-step, “feedback and feedforward towards the EBDM framework”, was explained by the authors to complete the framework.

Some previous findings showed that about half and two-thirds of organizations do not regularly collect related data about the use of evidence, and they do not systematically evaluate the usefulness or impact of evidence use on interventions and decisions [ 75 ]. The results of a study conducted on healthcare managers at the various levels of an Iranian largest medical university showed that the status of EBDM is not appropriate. This problem was more evident among physicians who have been appointed as managers and who have less managerial and systemic attitudes [ 76 ]. Such studies, by concerning the shortcomings of current models for EBDM in HSM or even lack of a suitable and usable one, have confirmed the necessity of developing a comprehensive framework or model as a practical guide in this field. Consequently, existing and presenting such a framework can help to institutionalize the concept of EBDM in health organizations.

In contrast, results of Lavis study (2008) on organizations that supported the use of research evidence in decision-making reported that more than half of the organizations (especially institutions of health technology assessment agencies) may use the evidence in their process of decision-making [ 75 ], so applying the present framework for these organizations can be recommended, too.

Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of access to some studies (especially gray literature) related to the subject in question that we tried to access them by manual searching and asking from some articles’ authors and experts. In addition, most of the existing studies on EBDM were limited to examining and presenting results on influencing, facilitating, or hindering factors or they only mentioned a few components in this area. Consequently, we tried to search for studies from various databases and carefully review and screen them to make sure that we did not lose any relevant data and thematic code. Also, instead of one model, we used four existing models as a basis in the BFF synthesis so that we can finally, by adding additional codes and themes obtained from other studies as well as expert opinions, provide a comprehensive model taking into account all the required steps and details. Also, the framework developed in this study is a complete conceptual model made by BFF synthesis; however, it may need some localization, according to the status and structure of each health system, for applying it.

The present framework provides a comprehensive guideline that can be well adapted for implementing EBDM in health systems and organizations especially in underdeveloped and developing countries where there is usually a lag in updating and applying evidence in their decision-making process. In addition, this framework by providing a complete, well-detailed, sequential and practical process including 10 steps and 56 sub-steps that did not exist in the incomplete related models, can be tested in the organizational decision-making process or managerial tasks by developed countries to improve their EBDM cycle, too.

Availability of data and materials

All data in a form of data extraction tables are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Evidence-based decision-making

Health System Management

Best-Fit Framework

Rychetnik L, Bauman A, Laws R, King L, Rissel C, Nutbeam D, et al. Translating research for evidence-based public health: Key concepts and future directions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(12):1187–92.

Article Google Scholar

Nutbeam D, Boxall AM. What influences the transfer of research into health policy and practice? Observations from England and Australia. Public Health. 2008;122(8):747–53.

Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-Based Public Health: A Fundamental Concept for Public Health Practice. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 2009;30(1):175–201. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100134 .

Brownson RC, Gurney JG, Land GH. Evidence-based decision making in public health. J Public Heal Manag Pract [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2018 May 26];5(5):86–97. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=yxRgAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA133&dq=+criteria+OR+health+%22evidence+based+decision+making%22&ots=hiqVNQtF24&sig=jms9GsBfw6gz1cN2FQXzCBZvmMQ

McGinnis JM. ‘Does Proof Matter? Why Strong Evidence Sometimes Yields Weak Action.’ Am J Heal Promot. 2001;15(5):391–396. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.391 .