- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- For the Press

- Our Programs

- Endorsements

- Partner With GDCI

- Guides & Publications

- search Search

- globe Explore by Region

- Global Street Design Guide

Download for Free

Thank you for your interest! The guide is available for free indefinitely. To help us track the impact and geographical reach of the download numbers, we kindly ask you not to redistribute this guide other than by sharing this link. Your email will be added to our newsletter; you may unsubscribe at any time.

" * " indicates required fields

About Streets

- Prioritizing People in Street Design

- Streets Around the World

- Global Influences

- A New Approach to Street Design

- How to Use the Guide

- What is a Street

- Shifting the Measure of Success

- The Economy of Streets

- Streets for Environmental Sustainability

- Safe Streets Save Lives

- Streets Shape People

- Multimodal Streets Serve More People

- What is Possible

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

- How to Measure Streets

- Summary Chart

- Measuring the Streets

Street Design Guidance

- Key Design Principles

- Defining Place

- Local and Regional Contexts

- Immediate Context

- Changing Contexts

- Comparing Street Users

- A Variety of Street Users

- Pedestrian Networks

- Pedestrian Toolbox

- Sidewalk Types

- Design Guidance

- Crossing Types

- Pedestrian Refuges

- Sidewalk Extensions

- Universal Accessibility

- Cycle Networks

- Cyclist Toolbox

- Facility Types

- Cycle Facilities at Transit Stop

- Protected Cycle Facilities at Intersections

- Cycle Signals

- Filtered Permeability

- Conflict Zone Markings

- Cycle Share

- Transit Networks

- Transit Toolbox

- Stop Placement

- Sharing Transit Lanes with Cycles

- Contraflow Lanes on One-Way Streets

- Motorist Networks

- Motorist Toolbox

- Corner Radii

- Visibility and Sight Distance

- Traffic Calming Strategies

- Freight Networks

- Freight Toolbox

- Freight Management and Safety

- People Doing Business Toolbox

- Siting Guidance

- Underground Utilities Design Guidance

- Underground Utilities Placement Guidance

- Green Infrastructure Design Guidance

- Benefits of Green Infrastructure

- Lighting Design Guidance

- General Strategies

- Demand Management

- Network Management

- Volume and Access Management

- Parking and Curbside Management

- Speed Management

- Signs and Signals

- Design Speed

- Design Vehicle and Control Vehicle

- Design Year and Modal Capacity

- Design Hour

Street Transformations

- Street Design Strategies

- Street Typologies

- Example 1: 18 m

- Example 2: 10 m

- Pedestrian Only Streets: Case Study | Stroget, Copenhagen

- Example 1: 8 m

- Case Study: Laneways of Melbourne, Australia

- Case Study: Pavement to Parks; San Francisco, USA

- Case Study: Plaza Program; New York City, USA

- Example 1: 12 m

- Example 2: 14 m

- Case Study: Fort Street; Auckland, New Zealand

- Example 1: 9 m

- Case Study: Van Gogh Walk; London, UK

- Example 1: 13 m

- Example 2: 16 m

- Example: 3: 24 m

- Case Study: Bourke St.; Sydney, Australia

- Example 2: 22 m

- Example 3: 30 m

Case Study: St. Marks Rd.; Bangalore, India

- Example 2: 25 m

- Example 3: 31 m

- Case Study: Second Ave.; New York City, USA

- Example 1: 20 m

- Example 2: 30 m

- Example 3: 40 m

- Case Study: Götgatan; Stockholm, Sweden

- Example 1: 16 m

- Example 2: 32 m

- Example 3: 35 m

- Case Study: Swanston St.; Melbourne, Australia

- Example 1: 32 m

- Example 2: 38 m

- Case Study: Boulevard de Magenta; Paris, France

- Example 1: 52 m

- Example 2: 62 m

- Example 3: 76 m

- Case Study: Av. 9 de Julio; Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Example: 34 m

- Case Study: A8erna; Zaanstad, The Netherlands

- Example: 47 m

- Case Study: Cheonggyecheon; Seoul, Korea

- Example: 40 m

- Case Study: 21st Street; Paso Robles, USA

- Types of Temporary Closures

- Example: 21 m

- Case Study: Raahgiri Day; Gurgaon, India

- Example: 20 m

- Case Study: Jellicoe St.; Auckland, New Zealand

- Example: 30 m

- Case Study: Queens Quay; Toronto, Canada

- Case Study: Historic Peninsula; Istanbul, Turkey

- Existing Conditions

- Case Study 1: Calle 107; Medellin, Colombia

- Case Study 2: Khayelitsha; Cape Town, South Africa

- Case Study 3: Streets of Korogocho; Nairobi, Kenya

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Acknowledgements

- Conversion Chart

- Metric Charts

- Summary Chart of Typologies Illustrated

- User Section Geometries

- Assumptions for Intersection Dimensions

- search Keyword Search

- Neighborhood Streets

- Neighborhood Main Streets

The reconstruction of this one-way street addressed several major challenges, including inadequate design and planning, poor maintenance standards, and inefficient utility management.

The project took a comprehensive, multidimensional approach under the program Tender S.U.R.E.: break once, and fix once and for all. This approach promotes upfront investment in quality materials and construction to increase durability.

- Balance existing uses.

- Enhance user experience, increase pedestrian safety, and calm traffic.

- Reduce disruptive construction practices by investing in upfront, quality

- construction for long-term durability.

Key Elements

Enhanced and extended sidewalks.

One-way protected cycle tracks.

Consistent travel lanes.

Dedicated and paved bus, auto rickshaw, and parking bays.

Landscaped strip between the motorized and non-motorized paths.

Protection and enhancement of existing trees with pits and guards.

Reconfiguration of underground utilities with the creation of access chambers for utility lines.

Keys to Success

- Interagency coordination.

- Public participation and involvement from the early stages of the project.

- Documentation and verification of existing utilities as part of planning and design process.

Involvement

Public Agencies Government of Karnataka, Bangalore Municipal Corporation (BBMP), Bangalore Development Authority, KPTCL, Traffic Police, Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC), BESCOM

Nonprofit Organizations Jana Urban Space, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy

Designers and Engineers Jana USP (Designer), NAPC (Contractor)

Project Timeline

Adapted by Global Street Design Guide published by Island Press.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CASE STUDY: Urban Design THE CITY OF MARIKINA CASE STUDY MARIKINA CITY

Related Papers

Civil Engineering and Architecture

Horizon Research Publishing(HRPUB) Kevin Nelson

Peri-urban is commonly defined as an area around the suburban region that has the hybrid characteristics between an urban area and a rural area. The study aimed to investigate the change of regional typology due to the progress of the peri-urban area in Marisa based on the physical and social aspects in 1980 and in 2017. Encompassing two districts, the study employed descriptive-quantitative method and analysis techniques, i.e., overlay, scoring, and spatial. The results showed that in 1980, four districts were included in the rural frame zone (zona bidang desa) category. Moreover, seven sub-districts were categorized as rural-urban frame zone (zona bidang desa kota) while the rest were included in the rural frame zone category. In 2017, a change of typology from rural-urban frame zone to urban-rural frame zone occurred in several villages/sub-districts, i.e., Libuo, South Marisa, North Marisa, and Pohuwato. Over a span of 37 years, the typology of several sub-districts has changed from rural frame zone to urban frame zone in Libuo, South Marisa, North Marisa, and Pohuwato village/sub-district. The urban sprawl in areas in Marisa has increased the need for an integrated policy to create a balanced spatial development.

As two areas directly adjacent to Gorontalo City, the sub-districts of Telaga (Gorontalo Regency) and Kabila (Bone Bolango Regency) are the center of regional growth. The study aimed to examine the physical development of two sub-districts, Telaga and Kabila, since the sub-districts previously mentioned have different regional characteristics and different physical morphology developments influenced by Gorontalo city. That the two sub-districts can be viewed as a peri-urban area of Gorontalo city is a fascinating topic to comprehend the peri-urban area. The stages of this qualitative descriptive research consisted of preliminary survey and observation, distributing questionnaires, collecting data, processing data, data analysis, and data interpretation. Over the last ten years, urban land use has increased in both Telaga and Kabila sub-district by 5% (49.18 ha) and 3% (45.58 ha), respectively. Agropolis activities still dominated the two peri-urban areas. The pattern of land use in the Sub-District of Telaga was the pattern of octopus, while that of Kabila sub-district was a linear pattern (southern part) and frog jump (northern part). Generally, the street pattern in the peri-urban area has a linear path pattern. The development of this peri-urban area seemed unplanned. The situation is understandable since these two areas were initially agrarian villages and hinterland areas of Gorontalo city.

Freek Colombijn

IJESRT Journal

The established economic activity is also influenced by road network patterns and transportation accessibility, to encourage the emergence of new urban activities, activity patterns and movement patterns. The height of land function in the residential area of Marisa is influenced by the ease of accessibility and the demand for residential because it is next to the Central Office district and the urban center. The study aims to (1) Identify components of morphological form comprising land use, road and building network patterns (patterns and densities), (2) Analyzing the morphological form of the old City of Marisa and combine it with characteristic morphological forming components. The methods of research used are qualitative methods of phenomenology. The results showed that (1) the City of Marisa has a characteristic of a village-city frame zone (zobikodes) that is fertile, developing naturally for surplus commodities. The land use pattern of Marisa City, Marisa City Road network, and the patterns and functions of Marisa City are a component of the morphological constituent of Marisa. (2) The City of Marisa forms a compact city i.e. octopus morphology (octopus shaped/star shaped cities) and the custom Tawulongo into local wisdom in organizing the layout of Old Town center Maris

Technology Reports of Kansai University

Antariksa Sudikno

The discussion about a house cannot only be learned from the perceivable physical form, but the house can be a description of the development process of the formation of a family with the social, cultural and economic conditions that underlie it. The physical condition of a residence can also provide an idea of how far the home owner has adapted the technology and culture around him. Family routine activities can also be described in the condition of the existing space configuration in the house. Circulation patterns are intentionally or unintentionally formed from the configuration of space which forms an element of the living space. This is also what happens to community settlements in the Poncokusumo District, Malang Regency. The condition of the area adjacent to Ngadas Village which is very thick with Tengger customs and culture was an interesting reason for the Poncokusumo District as the object of the research. The configuration pattern of the residential space was the result of this research discussion which was analyzed using qualitative methods. house, room, configuration. Key words: house, room, configuration

Journal Innovation of Civil Engineering (JICE)

Jalaluddin Mubarok

Perkembangan perkotaan pada suatu daerah pasti mengalami kemajuan seiring berjalannya peradaban manusia, sehingga pada umumnya perkembangan perkotaan tidak hanya berkembang secara kuantitas atau jumlah penduduk, melainkan juga dari segi perkembangan seni arsitektur, elemen-elemen arsitektur lainnya. Hal ini membuat peneliti merasa penting dalam hal mengkaji dan menganalisa terkait perkembangan perkotaan khususnya pada perkembangan perkotaan menurut teori dari Kevin Lynch yakni Image of the City. Hal ini dilihat dari perkembangannya pasti sudah sangat berbeda dengan teori dan penerapan di perkotaan dan kawasan suatu kota di wilayah tertentu. Hal ini juga mendorong peneliti untuk memetakan terhadap kawasan salah satu perkotaan yang ada di Jawa Timur, yakni kota Malang. Dikarenakan lokasi tersebut berada pada area yang mengalami pertumbuhan dan perkembangan yang sangat pesat, sehingga perlu adanya pengkajian dan pemetaan terhadap elemen-elemen perkotaan yang ada di kota Malang tersebut...

PLANNING MALAYSIA JOURNAL

ILLYANI IBRAHIM

Understanding the urban form is crucial in determining the structure of a city in terms of physical and nonphysical aspects. The physical aspects include built-up areas that can be seen on the earth surface, and the nonphysical aspects include the shape, size, density, and configuration of settlements. The objectives of this study are to (i) analyse the elements of historical urban form that are suitable for the site and (ii) to study on the elements of urban form in Melaka. Content analysis was adopted to analyse the literature of urban form and Melaka. Results show that the following four elements of urban form are suitable to be used for historical urban form analysis: (i) streets, (ii) land use, (iii) buildings, and (iv) open space. The findings also indicate that the selected urban form has successfully delineated in the historical of Melaka as the selected urban elements can be specifically scrutinized with the content analysis. Further study will focus on the historical urban...

Dominador N Marcaida Jr.

This is an updated copy of the profile for Barangay Marupit, Camaligan, Camarines Sur earlier published here at Academia.edu containing additional information and revisions that arose from later research by the author.

irwan wunarlan

IAEME Publication

The Settlement Area in Kampung Aur is a densely populated settlement located on the banks of the Deli River in Medan. Until now there has not been a more appropriate solution to the arrangement of the area and its residents although there are in several cities there have been several types of solutions to the problem of densely populated settlements ranging from forced evictions, the construction of new settlements in the form of flat / flat and village improvement programs. That said, the government began to realize that the problem could not be solved by a one-way system. There must be communication with slum dwellers. This then encourages the authors to make an arrangement of the area and its residents with an approach to the behavior of citizens and the types of settlements at this time. This study aims to produce a design of the area and settlements that can accommodate social and cultural aspects of society through the approach of environmental behavior and types of settlements. To achieve this goal, participatory observation will be carried out in every dominant community in the location. Through this observation it will be seen how the environmental settings and behavior work in Kampung Aur. Data on environmental and behavioral settings will then be processed to produce Kampung Aur design completion criteria. From this study it was found that there are two dominant tribes in Kampung Aur, namely Chinese and Minang.

RELATED PAPERS

predrag bejakovic

Min Rahminiwati

Fiziolohichnyĭ zhurnal

Oleg Tsupykov

SSRN Electronic Journal

Florence Guillaume

Adriana Rosa Cruz Santos

Bianca Martins

Marcel Broersma

Journal of Prosthodontics

Mário Sedrez

Science Signaling

Hemlata Agnihotri

Nikoo Yamani

Bamberger interdisziplinäre Mittelalterstudien

Ylva Schwinghammer

Value in Health

Panos Kanavos

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine

Asha Wijegunawardana

Journal of Electrical Engineering

zarko markov

László Nagygyörgy

Journal of Power and Energy Engineering

Faisal PEER MOHAMED

International Journal of Horticulture & Agriculture

Getachew Gudero

Journal of Insect Science

Sebastian Pelizza

Katri Kontturi

华威大学毕业证制作流程 UoW毕业证文凭

Fuzzy Sets and Systems

Miguel Couceiro

Arman Beisenov

Working paper

Joseph Haubrich

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Barcelona Urban Public Spaces 1976

- infrastructure

- place making

- transit system

- social fabric

- redevelopment

The city of Barcelona was awarded for a collective effort between many professionals in the requalification of 42 Urban Public Spaces in the city between 1981 and 1987. The projects affected positively nearly 1.7 million people extending over 100 sq. kilometers, covering the territory of the districts: Ciutat Vella, Eixample, Sants Montjuïc, Les Corts, Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, Gràcia, Horta-Guinardó, Nous Barris, Sant Andreu, and Sant Martí. The proposal’s merit resides in enhancing the quality of life through the public realm and the access to areas for leisure and social activities. Three kinds of specific urban space projects have been completed: plazas, parks, and streets. The urban public space projects represent a large and impressive body of public works at widely different scales spread throughout the city. The aim was to develop a program for the entire city, one that would eventually operate in a decentralized manner, fitting the needs of particular geographic locales regardless of prevailing socioeconomic and physical circumstances. During the early stages, all public improvements were confined to the project sites themselves, and there were no displacements of population or viable urban functions from surrounding areas. Moreover, projects were undertaken in all ten districts within Barcelona: Ciutat Vella, Eixample, Sanes Moncjuic, Les Cores, Sarria-Sane Gervasi, Gracia, Horca-Guinard6, Nous Barris, Sane Andreu and Sant Marci, respectively. The program officially began in December 1980. Apart from being a local jurisdiction, each district corresponds to a distinctive area within the city that warrants special urban design consideration, and each district is largely characterized by a particular pattern of streets and surrounding buildings.

Project Leads

- Town Planning Commission

- Office of Urban Projects

Organizations

- Piñón y Viaplana

- Urban Planning Laboratory

- Design Development

- Construction

- Schematic Design

Land use type

Population/density.

Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design

Bibliography.

Winner, 2012 Australia Award for Urban Design

Project Proposer, Project Manager and Construction Contractor: McGregor Coxall

Urban Designers: Equatica

Architect: Parramatta City Council

Project Websites:

Project Description:

The Parramatta River Urban Design Strategy (the Strategy) is a strategy for the regeneration of Sydney’s second largest CBD and its waterfront—a site that encompasses 31 hectares in the centre of Parramatta. The Strategy reorientates the Parramatta’s CBD towards the river and positions Parramatta Quay as a new water arrival point in the heart of Parramatta, connecting Parramatta’s CBD to Circular Quay by ferry. It also proposes four new vibrant mixed-use precincts on the river foreshore. In addition, the Strategy incorporates a new brand for the City of Parramatta: ‘Where The Waters Meet’, based on the meeting point of the harbour and river.

Commercial, Public Open Spaces, Mixed Use, Retail, Residential, Community, Recreation

Transport Options:

Principle: Enhancing

Parramatta is close to the geographic centre of metropolitan Sydney. It is currently undergoing change economically, demographically and physically. Parramatta City Centre is unique because it is the only major CBD within Sydney that is located on a riverfront. The name Parramatta means ‘head of the waters’ where fresh water meets salt water. Despite Parramatta’s riverfront location, the CBD has traditionally been oriented away from the river. At present there is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for Parramatta to make the most of its central and unique river location.

The Parramatta River Urban Design Strategy maximises this opportunity by reconnecting the city centre with its greatest asset, the river. The Strategy re-acknowledges the start of the Parramatta City Centre from the river, highlights the connection between the western most extent of Sydney Harbour and Parramatta City, and refocuses Parramatta’s CBD towards the river. To enhance the aquatic ecology of the river and improve the connection of Parramatta Quay to the CBD, the Strategy proposes to move the point at which salt and fresh water meet, by relocating the Charles Street Weir and moving Parramatta Quay to a more central location.

The Strategy proposes a mixture of land uses along the river foreshore, offering spaces for events, recreation, commerce, employment art and culture. New laneways named ‘Water Streets’ will improve the connections between Parramatta City and the river and will feature public art, water sculptures and water sensitive urban design initiatives. New medium rise apartment buildings with northerly aspects are also proposed and will contribute to the mix of housing types and tenures in the area. They will be set behind lower buildings on the water’s edge, defining the edge of the city and the visual corridor of the river.

Principle: Connected

The Strategy redefines and consolidates Parramatta’s urban centre and improves its connection to its river and Parramatta Quay. The new city core is to be defined by Parramatta Station to the south, the proposed North Parramatta Station to the north, and Church Street and Smith Streets to the west and east. The relocation of Charles Street Weir and Parramatta Quay help to redefine the city centre and reorient it towards the river.

The Parramatta River will become a focus for activity and will be better connected to the CBD through a series of laneways. One of the proposed laneways, Civic Place, will link the CBD to Parramatta Quay by a short five-minute walk.

A new pedestrian walkway under Lennox Bridge will link the proposed new urban terraces to the Foreshore Parklands and Parramatta Quay to the east and the King’s School and Parramatta Parklands to the west. Another new pedestrian crossing over the Marsden Street Weir will connect the visual arts building and the performing arts building on the opposite banks of the river.

Principle: Diverse

The Strategy has designed the public space and built form of Parramatta’s waterfront in a way that will directly encourage people to come to the water’s edge and engage with the Parramatta River. The Urban Design Strategy embodies key initiatives to create a diverse range of uses for the public and private space of Parramatta. These include:

Principle: Enduring

The Strategy has considered long-term effects of climate change and projected sea level rise levels as well as flooding issues that affect Parramatta’s city area. It proposes innovative ways to address these key constraints. The new developments along the waterfront will be designed to withstand flood events at 3.0 metre reduced levels. Also environmentally, the removal of the Charles Street Weir and the introduction of a new weir in a reconstructed river channel will help to repair the aquatic ecology of the river.

Water cycle management is centrally integrated into the planning and design of the Strategy and it features a Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) philosophy. The Strategy utilises WSUD to improve catchment and waterway health, and encourage conservation and management of this precious natural resource. The WSUD initiatives incorporated in the Strategy are:

Principle: Comfortable

The Strategy aims to redesign Parramatta to be more pedestrian friendly and a more comfortable and exciting place to visit. It links Parramatta’s CBD to the riverfront and redevelops Parramatta’s river foreshore into an interesting and inviting place to visit.

Principle: Vibrant

The Strategy makes Parramatta Quay a focus for activity in Parramatta. The public space around the Quay are to include a city square at Philip Street, a grass slope down to the river adjacent to the Smith Street Bridge and a promenade that steps down to the water’s edge. The new riverfront development will create a vibrant environment for people to work and play in, and which is appealing to visit at any time of the day or night.

Parramatta Quay is to become the heart of the Parramatta’s night time economy with restaurants, bars and a grand terrace that can be used as a moonlight cinema or for performances. Patrons of the restaurants on the waterside terraces will be able to watch the express Rivercat ferry come and go against the backdrop of the new weir and a new sculptural fish ladder. The proposal includes remodeling the Riverside Theatre as well, which is to have a grand glass atrium that links to a terrace bar.

The Strategy will also enable commuter ferries and pleasure craft to moor in the heart of Parramatta, enhancing the experience of arrival by ferry into Parramatta and bringing activity and excitement to the water’s edge in a new Parramatta Quay.

Principle: Safe

The increased use of the Parramatta foreshore will enhance its safety, day and night. The presence of more people in the Parramatta CBD and river foreshore area will likely reduce crime. Passive surveillance from people in buildings, cafes and shops adjacent to the foreshore area and public spaces will also improve safety in the area.

Principle: Walkable

The Strategy redefines and consolidates Parramatta’s urban centre and provides better links between the CBD to the river and Parramatta Quay, making the entire area more walkable. The laneways linking the CBD to the river will provide enjoyable, functional and diverse routes to walk along. This will encourage more people to walk and cycle to and within Parramatta’s City Centre and along the foreshore. The relocation of the Parramatta Quay closer to Parramatta’s CBD will also encourage more people to catch the ferry and walk into the CBD.

Principle: Context

The Strategy utilises a thorough understanding of the Parramatta River catchment and considers the opportunities for occupying the foreshore below flood level. It builds on regional and local planning instruments and studies previously undertaken by Parramatta City Council, including:

The Strategy creates the basis for developing a delivery framework that is uniquely suited to Parramatta, its community and context. It will inform future development along Parramatta’s foreshore and CBD, as well as potential future amendments to the Parramatta City Centre Local Environmental Plan and Development Control Plan.

Principle: Excellence

The Strategy successfully provides a framework for re-orientating Parramatta’s CBD to the river, regenerating the river foreshore and creating new vibrant mixed-use precincts along the riverfront. To accompany the redevelopment, a new vision for the brand of Parramatta has been developed: ‘Where The Waters Meet’.

The Strategy will form the basis of a detailed masterplan and a business case, which are the next steps for its delivery.

Principle: Custodianship

The Strategy creates momentum to enact positive change in Parramatta and helps to set an agenda for this change. It provides the foundation for informed discussion about the future direction and positioning of Parramatta’s CBD and waterfront. It creates the basis for developing a delivery framework that is uniquely suited to Parramatta, its community and its context.

Parramatta City Council recognises the role of the Strategy and the aims underpinning it in contributing to the ongoing economic, cultural and environmentally sustainable regeneration of Parramatta’s CBD and foreshore.

- Contributors

- Links

- Translations

- What is Gendered Innovations ?

Sex & Gender Analysis

- Research Priorities

- Rethinking Concepts

- Research Questions

- Analyzing Sex

- Analyzing Gender

- Sex and Gender Interact

- Intersectional Approaches

- Engineering Innovation

- Participatory Research

- Reference Models

- Language & Visualizations

- Tissues & Cells

- Lab Animal Research

- Sex in Biomedicine

- Gender in Health & Biomedicine

- Evolutionary Biology

- Machine Learning

- Social Robotics

- Hermaphroditic Species

- Impact Assessment

- Norm-Critical Innovation

- Intersectionality

- Race and Ethnicity

- Age and Sex in Drug Development

- Engineering

- Health & Medicine

- SABV in Biomedicine

- Tissues & Cells

- Urban Planning & Design

Case Studies

- Animal Research

- Animal Research 2

- Computer Science Curriculum

- Genetics of Sex Determination

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Agriculture

- Climate Change

- Environmental Chemicals

- Housing and Neighborhood Design

- Marine Science

- Menstrual Cups

- Population and Climate Change

- Quality Urban Spaces

- Smart Energy Solutions

- Smart Mobility

- Sustainable Fashion

- Waste Management

- Water Infrastructure

- Intersectional Design

- Major Granting Agencies

- Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Universities

Housing and Neighborhood Design: Analyzing Gender

- Full Case Study

The Challenge

Integrating gender analysis into architectural design and urban planning processes can ensure that buildings and cities serve well the needs of all inhabitants: women and men of different ages, with different family configurations, employment patterns, socioeconomic status and burdens of caring labor (Sánchez de Madariaga et al., 2013).

Method: Analyzing Gender

Analyzing gender in architectural and urban design can contribute to constructing housing and neighborhoods that better address people’s everyday needs, by fully integrating caring issues—caring for children, the elderly, and disabled—into research design.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Integrating gender expertise into housing and neighborhood design and evaluation is well underway, especially in Europe, and will improve living conditions for its residents, particularly parents, children, and the elderly.

2. Gender-aware housing and neighborhood design will improve pedestrian mobility and use of space for women and men of different ages, care duties, and physical abilities.

Planners, architects, and researchers from various fields have shown that gender roles and divisions of labor result in different needs with respect to built environments. These differences appear at various scales—individual buildings, neighborhoods, cities, and regions—and in the different domains of city building, such as housing, public facilities, transportation, streets and open space, employment and retail space (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2004). Gender analysis of space has identified the ways in which urban environments may enforce gender norms and fail to serve women and men equally (Spain, 2002; Hayden, 2005). Widely unrecognized gender assumptions in architecture and planning contribute to unequal access to urban spaces. While this Case Study addresses urban design in high-income countries, issues, such as safety in public space, or access to water, energy, transportation, and basic sanitation, become high priority in developing countries (Jarvis, 2009; Reeves et al., 2012).

Gendered Innovation 1: Integrating Gender Expertise into Housing and Neighborhood Design and Evaluation

In 2009 and 2010, Vienna was rated as one of the cities with the “highest quality of living in the world” (Irschik et al., 2013). Gender analysis contributed to this excellence: Over the past two decades, gender expertise has become fully integrated into Vienna’s urban planning (Booth et al., 2001):

1991 Two Viennese urban planners described the gendered aspects of urban design in an exhibition, “Who Owns Public Space–Women’s Daily Life in the City.”

1992 The Vienna City Council established the Women’s Office.

1998 The City Planning Bureau established the Co-ordination Office for Planning and Construction Geared to the Requirements of Daily Life and the Specific Needs of Women.

2002 Vienna designated Mariahilf, Vienna’s 6th district, a gender mainstreaming “pilot district,” a test area where gender analysis became an integral part of urban planning (Bauer, 2009; Kail et al., 2006 & 2007).

2010 Gender experts were moved from the Coordination Office directly into groups for “Urban Planning, Public Works and Building Construction.” This final step brought gender experts “in-house,” making them part of the core decision-making in the City of Vienna.

Method: Rethinking Priorities and Outcomes The European Union prioritized gender mainstreaming in 1996 and funded sixty networked projects in efforts to develop gender analysis for urban planning (Horelli et al., 2000; Roberts, 2013). Policy makers and funders that make gender analysis a requirement for funding potentially provide a platform for integrating gender-specific criteria into housing and neighbourhood planning. View General Method

Method: Analyzing Gender The relationship between place, space, and gender is complex and involves a number of steps: 1. Evaluating past urban design practices: Researchers recognized that urban design typically lacked a gender perspective, and was “blind” to differences between groups—women and men, people using different forms of transport and performing different kinds of work, etc. For example, design often focused on the needs of formally-employed persons who “inhabit the environment as consumers […] expecting residential areas to fulfill only one function and judging them by their recreational and leisure value.” This overlooks the needs of women and men who perform housework, child- and eldercare, etc. as well as the needs of “children, adolescents, and the elderly” (MOST-I, 2003; Ullmann, 2013). 2. Mainstreaming gender analysis into design (as discussed in Gendered Innovation 1 above). 3. Analyzing users and services: Designers may look at how various populations use space in relation to paid work, home life and work, social relations, cultural practices, and leisure. Designers may also examine the needs of various populations living in housing units and the needs of the people who service those units, such as cleaners and maintenance people. 4. Obtaining user input: Using co-creation and participatory research techniques , designers may ask users about their daily lived experience. Researchers may use a variety of methods, such as surveys, interviews, or observation. 5. Evaluation and planning (as discussed in Gendered Innovations 1 above). View General Method

Vienna’s example is being adopted by other European cities (Borbíró, 2011). This case study highlights only a few of the designs globally that have mainstreamed gender analysis into urban design and evaluation: 1. At the regional level, the Central European Urban Spaces (UrbSpace) project, supported by the EU’s Regional Development Fund, aims to improve the urban environments of eight Central European countries (Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Germany, and Italy) though renovations of open urban spaces, such as public parks and squares (Rebstock et al., 2011). UrbSpace uses a strategy of integrating the “gender perspective into every stage of the policy process – design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. (Scioneri et al., 2009). To this end, gender analysis is additionally used as a tool to contribute to other goals: environmental sustainability, public participation in planning, security of urban spaces, and accessibility (Stiles, 2010). For a summary of aspects to consider, see the Urban Planning & Design Checklist.

Gendered Innovation 2: Gender-Aware Housing and Neighborhood Design

Urban designers applying gender analysis have undertaken projects that coordinate design for housing, parks, and transportation to improve the quality of “everyday life.” Innovations in this field include:

A. Housing to Support Child- and Eldercare: Designers recognized that traditional urban design separated living spaces and commercial spaces into separate zones, resulting in large distances between homes, markets, schools, etc. These distances placed significant stress on people combining employment with care responsibilities (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2013). In addition, such design practices often make cars the most practical means of transportation, creating environmental challenges (Blumenberg, 2004)—see Case Study: Climate Change . In response, urban designers have created housing and neighborhoods with on-site child- and elderly-care facilities, shops for basic everyday needs, and often primary-care medical facilities.

Conclusions and Next Steps

The example of Vienna presented in this case study highlights how integrating gender expertise into city planning led to pilot projects, such as Frauen-Werk-Stadt I & II and In der Wiesen Generation Housing that succeeded in incorporating everyday living and caring tasks into the specific housing and neighborhood projects. These projects can serve as a model for larger-scale planning. A next step will involve moving beyond pilot projects toward fully integrating gender analysis into planning and budgeting at the municipal, regional, and national, and regional levels. Further research is also needed to understand how urban structures interact with gender relations, and how these differ across time and space.

Works Cited

Bauer, U.(2009). Gender Mainstreaming in Vienna: How the Gender Perspective Can Raise the Quality of Life in a Big City. Women and Gender Research, 18 (3-4) , 64-72.

Birch, E. (2011). Design of Healthy Cities for Women. In Meleis, A., Birch, E., 7 Wachter, S. (Eds.), Women’s Health and the World’s Cities , pp. 73-92. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press.

Blumenberg, E. (2004). En-Gendering Effective Planning: Spatial Mismatch, Low-Income Women, and Transportation Policy. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70 (3) , 269-281.

Booth, C., & Gilroy, R. (2001). Gender-Aware Approaches to Local and Regional Development: Better-Practice Lessons from across Europe. Town Planning Review, 72 (2) , 217-242.

Borbíró, F. (2011). “Dynamics of Gender Equality Institutions in Vienna: The Potential of a Feminist Neo-Institutionalist Explanation.” Paper Presented at the Sixth Annual European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Conference, Reykjavik.

Burton, E., & Mitchell, L. (2006). Inclusive Urban Design: Streets for Life. Oxford: Elsevier Architectural Press.

Greed, C. (2005). Making the Divided City Whole: Mainstreaming Gender into Planning in the United Kingdom. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 97 (3) , 267-280.

Greed, C. (2006). Institutional and Conceptual Barriers to the Adoption of Gender Mainstreaming Within Spatial Planning Departments in England. Planning Theory and Practice, 7(2) , 179-197.

Hayden, D. (2005). What Would A Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. In Fainstein, S., & Servon, L. (Eds.), Gender and Planning: A Reader , pp. 47-64. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Horelli, L., Booth, C. and Gilroy, R. (2000). The EuroFEM Toolkit for Mobilising Women into Local and Regional Development , Revised version. Helsinki: Helsinki University of Technology.

Irschik, E., & Kail, E. (2013). Vienna: Progress towards a Fair Shared City. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 292-329. Ashgate, London.

Jarvis, H. and Kantor, P. (2009) Cities and Gender . London: Routledge.

Kail, E., & Prinz, C. (2006). Gender Mainstreaming (GM) Pilot District. Vienna: City of Vienna Municipal Directorate, City Planner’s Office.

Kail, E., & Irschik, E. (2007). Strategies for Action in Neighbourhood Mobility Design in Vienna - Gender Mainstreaming Pilot District Mariahilf. German Journal of Urban Studies, 46 (2).

Magistrat der Stadt Wien. (2012). Alltags- und Frauengerechter Wohnbau. www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/alltagundfrauen/wohnbau.html

MOST-I: Management of Social Transformations Phase I (2003). Frauen-Werk-Stadt - A Housing Project by and for Women in Vienna, Austria. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) MOST Clearing House Best Practices Database. www.unesco.org/most/westeu19.htm

Rebstock, M., Berding, J., Gather, M., Hudekova, Z., & Paulikova, M. (2011). Urban Spaces – Enhancing the Attractiveness and Quality of the Urban Environment: Work Package 5, Action 5.1.3, Methodology Plan for Good Planning and Designing of Urban Open Spaces. Erfurt: University of Applied Sciences, 17.

Reeves, D., Parfitt, B., & Archer, C. (2012). Gender and Urban Planning: Issues and Trends. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

Reeves, D. (2003). Gender Equality and Plan Making: The Gender Mainstreaming Toolkit. London: Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI).

Reeves, D. (2005). Planning for Diversity: Policy and Planning in a World of Difference. Abingdon: Routledge.

Roberts, M. (2013). Introduction: Concepts, Themes, and Issues in a Gendered Approach to Planning. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 1-18. Ashgate, London.

Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI). (2007). Gender and Spatial Planning: RTPI Good Practice Note Seven. London: RTPI.

RTPI. (2007). Gender and Spatial Planning: Good Practice Note 7. London: Royal Town Planning Institute.

Ruiz Sánchez, J. (2013). Planning Urban Complexity at the Scale of Everyday Life: Móstoles Sur, a New Quarter in Metropolitan Madrid. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe, pp. 402-414. Ashgate: London.

Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés (2004). Urbanismo con perspectiva de género , Fondo Social Europeo- Junta de Andalucía, Sevilla.

Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés and Marion Roberts (Eds.) (2013). Fair Shared Cities. The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe. Ashgate, London.

United Nations (UN). (2010). The Millennium Development Goals Report . New York: UN Publications.

Scioneri, V., & Abluton, S. (2009). Urban Spaces – Enhancing the Attractiveness and Quality of the Urban Environment: Sub-Activity 3.2.3, Gender Aspects. Cuneo: Lamoro Agenziadi Sviluppo.

Ullmann, F. (2013). Choreography of Life: Two Pilot Projects of Social Housing in Vienna. In Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Roberts, M. (Eds.), Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe , pp. 415-433. Ashgate, London-New York.

Housing and Neighborhood Design: Analyzing Gender In a Nutshell

Traditionally, cities have separated living and commercial spaces, resulting in large distances between home, daycare, shops, schools, and medical care. In such cities cars often become the preferred means of transportation, creating serious problems for the environment.

“Urban form” and the housing crisis: Can streets and buildings make a neighbourhood more affordable?

Assistant Professor of Architecture / Urbanism, IE School of Architecture and Design, IE University

Junior Architect at OMA, IE University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

IE University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation ES.

IE University provides funding as a member of The Conversation EUROPE.

View all partners

As of 2007 , most humans live in cities. Though this is a relatively recent trend, many of our settlements contain street, block, and building patterns that have developed over centuries. These patterns – which collectively make up what we call “urban form” – are far from a neutral backdrop: they influence who lives where, what businesses find footholds in which locations, and what makes some areas more diverse than others.

“Bottom-up” and “top-down” are terms which are often used to pin down the two ends of the vast range of urban form. Bottom-up refers to neighborhoods which develop naturally and gradually, without a strict masterplan guiding their development. Top-down, on the other hand, refers to urban form that is designed by singular authors, with much tighter controls over, and ideals around, how it should develop over time.

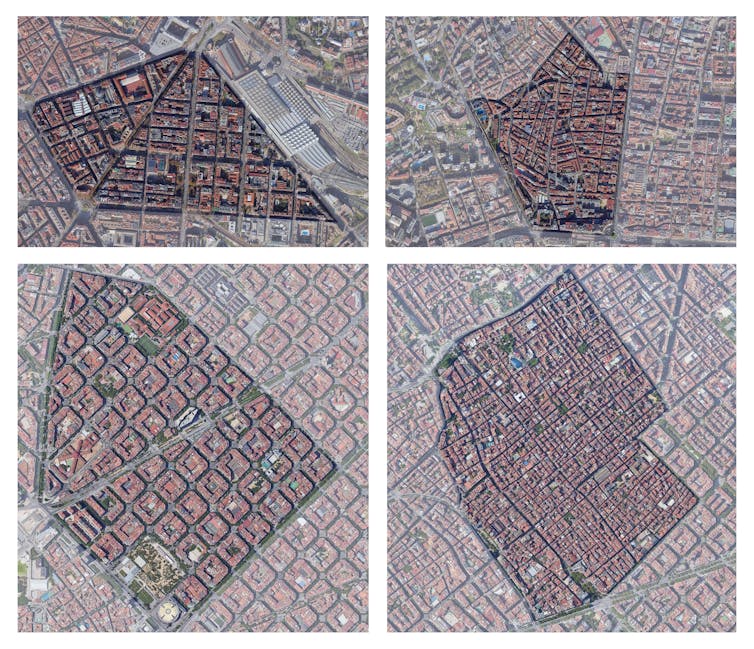

If we look at bottom-up neighbourhoods from a bird’s eye view, we tend to see a variety of block sizes, street widths and public spaces, and often maze-like street patterns. Top-down areas, by comparison, tend to be less varied, with clear evidence of their authors’ vision and values regarding urban geometry and the nature of public space – grid systems and sweeping boulevards abound. Many cities have bottom-up and top-down neighourhoods existing side by side, legacies of different political and socioeconomic eras.

Cities also reflect the values of time, place, and history. Today there are extensive discussions of bottom-up development and how it fosters communities and neighbourhood identity, while the lasting imprints of top-down regimes are still clearly visible in contemporary cities around the world.

For centuries, architects, planners and philosophers have suggested that bottom-up areas of cities tend to be more inclusive than top-down ones, supporting a wider range of economic classes. However, decisively proving such a theory has proved challenging.

How the built world shapes demographics: two theoretical approaches

The link between urban form, class and economic diversity follows two lines of thought.

The first is an extension of ecology. In natural habitats that have developed slowly over time – through bottom-up processes – we tend to observe a wide range of species. However, in planned habitats – built much more rapidly in a top-down manner – this kind of richness is often markedly absent. Slow growth tends to produce more intricacy and diversity, and this idea is often extended to theories of urban form.

The second line of thought is economic. Consider the diversity of public spaces in bottom-up districts – different sized streets, alleyways, squares, parks, courtyards, and so on. This variety of public spaces creates different qualities of light and air, as well as a wide range of favourable and less favourable conditions.

A more varied real estate market should, in theory, emerge as a byproduct of this diversity: a dark, poorly ventilated apartment is cheaper than a bright, airy one; a dwelling overlooking a pleasant square is more marketable than one next to a narrow alley. These varied spaces can host a varied population – a range of different ages, household sizes and income levels, all living cheek to jowl alongside one another.

In a top-down neighbourhood such variety is often absent, as buildings, streets, and public spaces tend to be more uniform. This homogeneity should, in theory, limit population diversity.

Real world examples: Madrid and Barcelona

In late 2021, we conducted research into the relationship between urban form and housing . We looked at two districts in Barcelona and two in Madrid, with one bottom-up and one top-down in each city, homing in on areas with similar average real estate values. The neighbourhoods examined were Bellas Vistas and Palos de la Frontera in Madrid, and Vila de Gracia and Nova Esquerra de l’Eixample in Barcelona.

Curiously, our research both confirmed and subverted the presumed theoretical link between urban form and housing stock, and the presumed supremacy of bottom-up over the top-down areas in fostering economic diversity.

Our main finding was that the bottom-up districts we looked at had, overall, more small-scale apartments. The reason is simple: they had more small-scale buildings, built on small-scale plots. Once divided into apartments, this produces small apartments – homes in the bottom-up areas were 10% to 23.1% smaller than their top-down counterparts. This also made their real estate markets for small homes more competitive, and therefore more affordable.

However, our study showed there is nothing inherently magical about bottom-up areas. Their more intricate housing stock has little to do with the layout of streets and blocks, and a lot to do with how that land is built upon.

Plot size appears to be the deciding factor: the districts with greater numbers of small buildings built on small plots supported a denser and more affordable housing stock, regardless of whether they were top-down or bottom-up.

Older bottom-up areas seem to naturally lend themselves to having more small-scale plots. This is likely due to the incremental development of these areas, and the complex land ownership patterns that developed as a result. However, there is no reason why a top-down area cannot be designed to replicate these characteristics.

Implications for the housing crisis

Governments seeking to rein in housing markets can take action to encourage development on a smaller scale. One rather blunt, though potentially fruitful, method is limiting ownership of urban land by a single individual or corporation, or limiting the footprint and size of non-public buildings that can be built within a city.

Although it applies to agricultural land, the limitation of private ownership to 50 acres per person in Sri Lanka is a useful case study here.

Even in countries like the United States, where property rights are wielded in objection to such arguments, there is a longstanding debate on the fundamental necessity of land ownership limitations in maintaining a functioning capitalist system.

As housing crises rage across the world, many cities are in dire pursuit of a more affordable, more varied, and more inclusive housing stock. It is increasingly clear that urban policies aiming to achieve this solely by addressing real estate development are falling woefully short of their aims on a global scale.

What our research indicates is that deeper, more structural approaches may be worth considering – approaches that not only address the physical form of the city, but also the ownership patterns that underpin it. Approaching urban land ownership and architecture on a smaller scale may hold potential that is not yet being used in full.

- Urban planning

- Housing crisis

- The Conversation Europe

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Technical Skills Laboratory Officer

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Urban Design Case Study Archive is a project of Harvard University's Graduate School of Design developed collaboratively between faculty, students, developers, and professional library staff. Specifically, it is an ongoing collaboration between the GSD's Department of Urban Planning and Design and the Frances Loeb Library. ...

6 Urban Design Projects With Nature-Based Solutions. Extreme natural events are becoming increasingly frequent all over the world. Numerous studies indicate that floods, storms, and sea-level rise ...

Urban Design - Case Studies and Examples John Pattison Updated December 22, 2022 20:38 "Lessons from the Streets of Tokyo" An urbanist abroad discovers that Tokyo faces many of the same challenges as U.S. cities—off-street parking, pedestrian safety, utilizing space, etc.—but is addressing them in very different ways. ...

CASE STUDY LINKS/REFERENCES. An award for Australian urban design initiatives and projects that demonstrate excellence and innovation, and contribute to a wider appreciation of, urban design. A resource with publications and case studies of excellent buildings and spaces, United Kingdom. Case studies of residential, reuse and infill ...

Plazas, squares, and parks, undeniable necessities in the urban fabric, have become, today, more vital than ever. Not only do these spaces have a positive impact on health, but they generate ...

Urban DesignCase Study Archive. Urban Design. Case Study Archive. 01 / 05.

CREATING CITIES FOR WALKING AND CYCLING A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THREE INDIAN CITIES July 2020. Implemented by. In cooperation with. Prepared by. Content, layout and design: Vidhya Mohankumar ...

In the narrow streets and urban life, drug trafficking found a favorable environment to thrive. Medellín plunged into a profound crisis during the 1980s and 1990s, as known by all. "Medellín ...

In 1958, a concrete cover was placed over the stream, and an elevated highway, measuring 5.6 km (3.5 mi) in length and 16 m (52 ft) in width, was completed in 1976. In July 2003, the mayor of Seoul, Lee Myung-bak initiated a project to remove the elevated highway and restore the stream. This was a significant endeavor as it required the removal ...

Explore the transformative urban design of Cayalá, a 'city within a city' in Guatemala. Discover how its blend of traditional architecture and modern planning principles of new urbanism creates vibrant, sustainable communities. Learn from our in-depth case study how strategic branding and community-centric design can redefine urban living.

The projects documented in these 16 case studies demonstrate the urban design qualities outlined in the Urban Design Protocol. The diversity of project types is intentional, covering a range of activities, scales and locations across New Zealand to ensure wide appeal and to illustrate as many lessons as possible.

The conversion of the 1.15 km-long main street into a pedestrian street was seen as a pioneering effort, which gave rise to much public debate before the street was converted. "Pedestrian streets will never work in Scandinavia" was one theory. "No cars means no customers and no customers means no business," said local business owners.

Urban design is about making connections between peo-ple and places, movement and urban form, nature and the built fabric. Urban design draws together the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity, and economic viability into the creation of places with dis-tinct beauty and identity. Urban design is derived from but

Urban canyons. Street canyons initially consist of streetscape including the horizontal and vertical surfaces within the space. Two of the main factors found to have a great impact on the street canyon are the height-to-width (H/W) ratio and street orientation [Citation 3].Results from a previous study showed that 1.5 is the optimal aspect ratio due to the building's increased shading ...

Case study in Urban Design. CONTENT 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction 1.1 Project Title / Project Information 1.2 Location 1.3 Dates: Inception, Planning and implementation 1.4 Scope: Site/s with ...

94 likes • 54,474 views. L. Lalith Aditya. Architecture Urban design Casestudy of GOA. Education. 1 of 61. Download Now. Download to read offline. Urban design Case study GOA PANJIM - Download as a PDF or view online for free.

Using the northern section of the Sumida Ward in Tokyo, Japan, this study examines the creation and application of the Urban System Design (USD) Conceptual Framework as an initial proof of concept. This proof of concept examines the process, methods, models, and outcomes of the basic Urban Systems Design approach as it currently stands. 2.

The most inspiring residential architecture, interior design, landscaping, urbanism, and more from the world's best architects. Find all the newest projects in the category Urban Design. 690 ...

Case Study: St. Marks Rd.; Bangalore, India. Location: Bangalore, India ... The reconstruction of this one-way street addressed several major challenges, including inadequate design and planning, poor maintenance standards, and inefficient utility management. ... Jana Urban Space, Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy. Designers and ...

CASE STUDY: Urban Design THE CITY OF MARIKINA What are the external elements, such as a through road, threaten the health and survival of the district? Presence of sidewalk vendors - it destroy the beauty of the city and create an unpleasant scene for tourists. Informal settlers- informal settlements along the Marikina River have often viewed ...

The city of Barcelona was awarded for a collective effort between many professionals in the requalification of 42 Urban Public Spaces in the city between 1981 and 1987. The projects affected positively nearly 1.7 million people extending over 100 sq. kilometers, covering the territory of the districts: Ciutat Vella, Eixample, Sants Montjuïc ...

The Parramatta River Urban Design Strategy (the Strategy) is a strategy for the regeneration of Sydney's second largest CBD and its waterfront—a site that encompasses 31 hectares in the centre of Parramatta. The Strategy reorientates the Parramatta's CBD towards the river and positions Parramatta Quay as a new water arrival point in the ...

Widely unrecognized gender assumptions in architecture and planning contribute to unequal access to urban spaces. While this Case Study addresses urban design in high-income countries, issues, such as safety in public space, or access to water, energy, transportation, and basic sanitation, become high priority in developing countries (Jarvis ...

Urban policy needs to look beyond housing ... IE School of Architecture and Design, IE University ... the limitation of private ownership to 50 acres per person in Sri Lanka is a useful case study ...

It describes the emergent subculture in an Italian slum in an urban neighbourhood in the United States, called the Cornerville district (a pseudonym). ... A case study design similar to multiple-case design, is cross-case design (Yin, 2014, p. 242). In it, two or more cases experiencing similar events or phenomenon are studied, and then the ...

Decarbonizing the urban environment has two significant challenges: Increasing electricity demand due to the electrification of space heating and increased renewables share in the electricity supply. The European Commission defines a new grid support mechanism for peak-shaving products in renewed Electricity Market Design.

The main aim of this article is to evaluate the impact of dynamic indicators associated with urban spaces on the environmental behavior of residents in Shanghai, China. With the city experiencing rapid urbanization and increasing environmental concerns, it is crucial to understand how the design and management of urban spaces can encourage pro-environmental attitudes and actions among the ...