- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

What Can the Church Do About Child Protection?

You’ve read the papers. You’ve seen the reports. We know that abuse is happening in churches. According to the 2019 “Abuse of Faith” investigation by the Houston Chronicle , nearly 400 Southern Baptist leaders and volunteers—pastors, deacons, youth ministers, and missionaries—have been accused of misconduct by more than 700 victims since 1998.

Guidepost’s recent investigation into the problem of handling sexual abuse in the SBC has demonstrated a dire need for reform in abuse prevention training, volunteer screening, and response to allegations. The PCA released recommendations to equip churches handling cases of domestic abuse this week, demonstrating that abuse doesn’t discriminate by polity, theological convictions, or denominations. But what do we do about it? How can we respond when the scope of the problem seems beyond us?

Our understanding of the Bible’s standards for Christian character and its demands for how we care for the vulnerable must lead to changes in the way we view abuse prevention.

Ministry leaders should take time to grieve and lament the abuse that has gone on for years. We must consider how we can better care for those who have been affected by abuse , both survivors and their loved ones. And every organization that serves children and other vulnerable people must develop a plan to prevent abuse and respond properly if an allegation of abuse is reported in their ministry.

That’s where I want to focus in this article. Our theological convictions about the dignity of all people made in God’s image, our understanding of the Bible’s standards for Christian character, and its demands for how we care for the vulnerable must lead to changes in the way we view abuse prevention and child protection.

3 Key Measures for Child Safety

How can your church begin to take steps toward a robust child safety ministry? Consider these three child safety measures.

1. Governance

The best way to take child protection seriously in your church is to start at the top: in your organization’s leadership. As the Evangelical Council for Abuse Prevention’s general counsel Sally Wagenmaker says , “Child Protection starts with good, godly governance.”

If your leadership isn’t on board with child safety, then staff and volunteers are likely not on the same page about abuse prevention and reporting practices, and abuse will rarely be dealt with appropriately.

If your organization works with children, the governing body should institute a child safety program , and this program should require a robust screening process (including background checks, interviews, and reference checks) as well as training for all staff and children’s and youth ministry volunteers.

Require all volunteers to agree to a code of conduct , with policies of discipline for those who break it, and maintain a zero-tolerance policy for child sexual abuse. This means the church will not allow anyone who has admitted to or is found to have been convicted of child sexual abuse to work with children in any capacity.

2. Training

Every person who interacts with kids needs training on how to recognize the signs of abuse, grooming behavior, and abusive behavior. They also need training on how to respond to abusive incidents that occur both inside and outside of the organization. In your church’s training program, emphasize a proactive position toward child safety, rather than a reactive one, so you’re not reacting to situations after the damage has already been done.

Instill in staff and workers their responsibility as those on the front lines of child protection. They will pick up on abuse indicators through conversations and interactions with the kids first. Make staff and volunteers aware of mandated reporting laws in your local jurisdiction. You can find out your state’s requirements at Mandated Reporter or in the Mandatory Reporters guide from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Encourage workers to report anything they find suspicious, with assurance that individuals within the organization and the organization as a whole will not punish or discipline workers for reporting in good faith, regardless of whom they report or if the allegation is true or false.

For more resources on training, see Deepak Reju’s book On Guard: Preventing and Responding to Child Abuse at Church , especially chapters 11 and 12.

3. Response

Develop a written response plan before an incident of abuse occurs. The first 24 hours after a report is made are often the most crucial, so make all staff and volunteers aware of the plan so they can access it quickly.

Ensure your response plan complies with investigation protocols from law enforcement and child protective services. Be certain to include steps for how to care for the well-being of the alleged victim, and require documentation of all response actions.

A good response plan covers the following topics: how to receive an allegation of abuse from a child; how to report abuse; mandatory reporter laws and reporting protocols, including contact information for jurisdictional agencies; contact information for legal counsel and your insurance carrier; and designated counselors or therapists for victims.

Churches should put a crisis response team in place. This is an important step even for smaller churches and church plants, where the team will primarily be composed of volunteers. A crisis response team is made up of people who are familiar with the response plan and who provide care for the alleged victims and handle logistical needs.

Finally, leaders must be notified in the event of a report so they can develop an internal plan of care for the alleged victim, separate the victim from his or her abuser, and organize a strategy for communicating with the church and responding to potential media inquiries.

Whatever It Takes

Abuse survivor and victim advocate Jenna Quinn writes , “In the same way there is a mental, psychological, and physical impact of abuse, there is also a spiritual impact of abuse. . . . And when the abuse happens within the faith environment the impact of the survivor’s spiritual damage is often heightened.” We must do everything we can to remove stumbling blocks for those affected by abuse.

God calls his people to care for the vulnerable and protect his church from those who would do it harm (Ps. 82:3–4; Isa. 1:17; Acts 20:28–30; 1 Cor. 5:9–13; James 1:27; Jude 4). Maybe this is your first introduction to the problem of abuse, and maybe it seems too big to handle. But there are measures we can put in place both to prevent abuse and to respond properly, and there are plenty of ministries, Christian lawyers, and even insurance agencies who would love to help! The witness of the church is strengthened when we work together and do whatever it takes to protect and care for children.

The Evangelical Council for Abuse Prevention is devoted to supporting Christian ministries in child protection and abuse prevention through awareness , accreditation, and resources . The group has developed a set of child safety standards that were designed to help ministry leaders make their organizations safe for kids. The standards are divided into five categories: governance, child safety operations, screening, training, and response.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

Briggham Winkler (MDiv, Southern Seminary) is communications coordinator for the Evangelical Council for Abuse Prevention, where he has served since May 2021. He lives in Jacksonville, Florida, with his wife Hannah, their dog, and two cats. He previously served as an editorial intern with the The Gospel Coalition.

Now Trending

1 can i tell an unbeliever ‘jesus died for you’, 2 the faqs: southern baptists debate designation of women in ministry, 3 7 recommendations from my book stack, 4 artemis can’t undermine complementarianism, 5 ‘girls state’ highlights abortion’s role in growing gender divide.

The 11 Beliefs You Should Know about Jehovah’s Witnesses When They Knock at the Door

Here are the key beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses—and what the Bible really teaches instead.

8 Edifying Films to Watch This Spring

Easter Week in Real Time

Resurrected Saints and Matthew’s Weirdest Passage

I Believe in the Death of Julius Caesar and the Resurrection of Jesus Christ

Does 1 Peter 3:19 Teach That Jesus Preached in Hell?

The Plays C. S. Lewis Read Every Year for Holy Week

Latest Episodes

Lessons on evangelism from an unlikely evangelist.

Welcome and Witness: How to Reach Out in a Secular Age

How to Build Gospel Culture: A Q&A Conversation

Examining the Current and Future State of the Global Church

Trevin Wax on Reconstructing Faith

Gaming Alone: Helping the Generation of Young Men Captivated and Isolated by Video Games

Raise Your Kids to Know Their True Identity

Faith & Work: How Do I Glorify God Even When My Work Seems Meaningless?

Let’s Talk (Live): Growing in Gratitude

Getting Rid of Your Fear of the Book of Revelation

Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places: A Sermon from Julius Kim

Introducing The Acts 29 Podcast

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor Report

Introduction, internet child pornography.

The problems facing the children internationally include internet child pornography and child labor. These are problems widespread across the globe because of abating of the vices by government officials of various states and instability of various policy frameworks set by the governments.

Also, the social malpractices like bribery have also led to the laxity in dealing with the menace. There is a need for the involvement of the community and organization of goodwill, in the alleviation of poverty and suffering of children. This owes to the fact that poverty is the root cause of child abuse.

The internet is a virtual platform for the predation of children by the unscrupulous people. The people who propagate this vice act illegally, given that it is hard to apprehend them legally. This owes to the fact that different countries have their jurisdictions and internet space. This makes it difficult for identifying, arresting, and prosecution of these criminals. Moreover, not every nation is a signatory to the international internet protocol pact.

Therefore, some countries allow the practice in their jurisdiction. Sanderson (2007, 23) posits that lack of funding also contributes to the low legal response to this vice. This aggravates the situation because the legal practitioners, who ought to investigate the suspects, accept bribes, and let the suspects go unpunished.

Child labor

This is the forced working of children at attender age, usually between the age of 5 and 14 years. This arises from the low financial status of families. This is because their parents forcefully bond some children because they have no power to object. Furthermore, young children may not be aware of the problem until later in life. This practice denies the children the chance of attending school; hence, they grow as illiterates.

This affects every aspect of their lives, including their financial stability. The practice is usually concealed. Hence it becomes difficult for the policy enforcers to crack down on the propagators of these criminals. Hugh (2009, 35) posits that the consent of the parents of the children to the vice aggravates the situation. However, financial instability is the overriding causal problem. Therefore, it is incumbent upon all governments to boost the economic and financial welfare of its citizenry to avert the vice.

Children can also be abducted and subjected to forced labor by the abductors. The children are compelled to work in adverse conditions detrimental to their health and safety. The children are also denied freedom of expression to suppress complaints from the children. Indeed, they are also denied the freedom of movement, given that they may escape (Chris, 2007, 51). This makes the children afraid and traumatized; hence; they are forever victims of circumstance. They do not receive any compensation for the services they offer.

Remedial measures for Internet child pornography

There is a remedy to the vice of internet child pornography. Governments ought to liaise in curbing this vice. This can be done through harmonizing of policies of various governments about internet misuse. The sites that provide child pornography need to be banned from the operation and heavy fines charged.

Also, the parents of children should teach, guide, and counsel their children on the virtues of life and the negative impacts of watching such pornographic videos online. This will enlighten the children of the immorality of indulging in the practice. The government also ought to create laws prohibiting the practice and provision of severe penalties for committing and abating the practice.

Corporate Social Responsibility in the International education center

This is an international organization, which provides education to children across the globe. It has branches all over the world. The organization embraces the aspect of corporate social responsibility because of the vitality of the practice. This responsibility is implied for every organization. Its practice leads to goodwill from the members of society and assures of the going concern of the organization because of the many benefits derived from the initiative.

This institution carries out a free educational program for all the street children around its locations in the world. This affords the street children an opportunity to access literacy and intellectual development. Furthermore, the education obtained opens all avenues of the lives of these children, including financial breakthroughs. This lowers the crime rate in such towns, given that street children grow up to be robbers and burglars (Hugh, 2009, 43). In this regard, society benefits from this corporate social responsibility of the institution.

Ways of making child welfare projects successful

There are many ways in which children can be assisted to overcome their predicaments. First is the creation of non-governmental organizations to clamor for adherence to child rights. These initiatives also advocate for the ban of all social evils done to children, including child labor.

According to Farquhar (2008, 67), these organizations will spearhead the restoration of fair treatment of children across the globe. The creation of many needy children centers will provide a safe place for vulnerable children. This will reduce the numbers of cases of child mistreatment and abuse.

Ways of Improving We Care organization

We Care initiative can be improved through sufficient funding, which will enable the meeting of the divergent needs of children from all occupations. In this regard, parents and other people will bring the children to the organization for rehabilitation and intellectual development.

The donation of various goodies like learning materials, food, and other learning paraphernalia necessities will make We Care organization a better place for all and sundry. The organization can also be improved through the use of corporate social responsibility aspect. This will create awareness to the community regarding the agenda of the organization.

There is a need for a concerted effort in ensuring the welfare of all children across the globe. The synergistic approach will eliminate the mistreatment of children and the propagation of immoral practices like internet child pornography and child labor. Internet child pornography can be eliminated through the collective ban of the practice among all nations across the globe. This will be possible through the constitutional amendments to accommodate the ban of internet child pornography.

Child labor can also be curbed through full implementation of the child rights. This will help in the apprehension of the people who take part in child abuse. Organizations can help children through complying with the corporate social responsibilities. Helping the needy and vulnerable children will earn the organizations the reputation of the society because of the support given the children.

Chris, B. (2007). Child Protection: An Introduction . California: Publisher-SAGE.

Farquhar, S.E. (2008). The Benefits & Risks of Childcare (ECE) for Young Children. New Zealand: Child Forum.

Hugh, H. (2009). The World of Child Labour . New York: M.E. Sharpe Publications.

Sanderson, C. (2007). The seduction of children: empowering parents and teachers to protect children from child sexual abuse . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 22). Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor. https://ivypanda.com/essays/criminal-law-child-protection-from-pornography-and-labor/

"Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor." IvyPanda , 22 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/criminal-law-child-protection-from-pornography-and-labor/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor'. 22 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/criminal-law-child-protection-from-pornography-and-labor/.

1. IvyPanda . "Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/criminal-law-child-protection-from-pornography-and-labor/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Criminal Law: Child Protection from Pornography and Labor." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/criminal-law-child-protection-from-pornography-and-labor/.

- Internet Pornography Regulation

- Child Pornography on the Internet: How to Combat?

- Scientific Approaches to Pornography

- Pornography and Ethics

- The Difference Between Internally Generated Goodwill and Purchased Goodwill

- Child Pornography: Legal and Psychological Implications

- Pornography or Obscenity and the First Amendment

- Child Pornography and Its Regulation

- Pornography and Women Issues

- Pornography: The Access Restriction

- Digital Surveillance System

- Oral Arguments and Decision-Making on the Supreme Court

- Public Awareness of Chronic Kidney Disease

- U.S. Supreme Court: Antonin Scalia as a Textualist

- The United States Supreme Court: Marbury vs. Madison

Mandatory reporting was supposed to stop severe child abuse. It punishes poor families instead.

This article was published in partnership with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive ProPublica’s biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

PHILADELPHIA — More than a decade before the Penn State University child sex abuse scandal broke, an assistant football coach told his supervisors that he had seen Jerry Sandusky molesting a young boy in the shower. When this was revealed during Sandusky’s criminal trial in 2012, it prompted public outcry: Why hadn’t anyone reported the abuse sooner?

In response, Pennsylvania lawmakers enacted sweeping reforms to prevent anything like it from ever happening again.

Most notably, they expanded the list of professionals required to report it when they suspect a child might be in danger, broadened the definition for what constitutes abuse and increased the criminal penalties for those who fail to report.

“Today, Pennsylvania says ‘No more’ to child abuse,” then-Gov. Tom Corbett declared as he signed the legislation into law in 2014.

A flood of unfounded reports followed, overwhelming state and local child protection agencies. The vast expansion of the child protection dragnet ensnared tens of thousands of innocent parents, disproportionately affecting families of color living in poverty. While the unintended and costly consequences are clear, there’s no proof that the reforms have prevented the most serious abuse cases, an NBC News and ProPublica investigation found.

Instead, data and child welfare experts suggest the changes may have done the opposite.

The number of Pennsylvania children found to have been abused so severely that they died or were nearly killed has gone up almost every year since — from 96 in 2014 to 194 in 2021, according to state data . State child welfare officials say more vigilance in documenting severe cases of abuse likely contributed to the increase. But child safety advocates and researchers raised concerns that the surge of unfounded reports has overburdened the system, making it harder to identify and protect children who are truly in danger.

In the five years after the reforms took effect, the state’s child abuse hotline was inundated with more than 1 million reports of child maltreatment, state data shows. More than 800,000 of these calls were related not to abuse or serious neglect, but to lower-level neglect allegations often stemming from poverty, most of which were later dismissed as invalid by caseworkers.

The number of children reported as possible victims of abuse or serious neglect increased by 72% compared to the five years prior, triggering Child Protective Services investigations into the well-being of nearly 200,000 children from 2015 to 2019, according to a ProPublica and NBC News analysis of federal Department of Health and Human Services data . From this pool of reports, child welfare workers identified 6,000 more children who might have been harmed than in the five previous years. But for the vast majority of the 200,000 alleged victims — roughly 9 in 10 — county agencies dismissed the allegations as unfounded after inspecting families’ homes and subjecting parents and children to questioning.

The expanded reporting requirements were even less effective at detecting additional cases of sexual abuse. Some 42,000 children were investigated as possible sex abuse victims from 2015 to 2019 — an increase of 42% from the five years prior — but there was no increase in the number of substantiated allegations, the analysis of federal data showed. In other words, reforms enacted in response to a major sex abuse scandal led to thousands more investigations, but no increase in the number of children identified as likely victims.

Child welfare experts say these findings cast doubt on the effectiveness of the primary tool that states rely on to protect children: mandatory child abuse reporting. These policies, the bedrock of America’s child welfare system, were first implemented more than half a century ago in response to growing national awareness of child maltreatment. The thinking was simple: By making it a crime for certain professionals to withhold information about suspected abuse, the government could prevent vulnerable children from falling through the cracks.

Over the past decade, at least 36 states have enacted laws to expand the list of professionals required by law to report suspicions of child abuse or imposed new reporting requirements and penalties for failing to report, according to data compiled by the National Conference of State Legislatures , a group representing state governments.

Some legal experts and child welfare reform activists argue these laws have created a vast family surveillance apparatus, turning educators, health care workers, therapists and social services providers into the eyes and ears of a system that has the power to take children from their parents.

“I don’t think we have evidence that mandated reporting makes children safer,” said Kathleen Creamer, an attorney with Community Legal Services, a Philadelphia nonprofit that provides free representation to parents accused of abuse and neglect. “I actually think we have strong evidence that it puts child safety at risk because it makes parents afraid to seek help, and because it floods hotlines with frivolous calls, making it harder for caseworkers to identify families who really do need services.”

How America’s child welfare dragnet ensnares struggling families

- CPS workers search millions of homes a year. A mom who resisted paid a price .

- For Black families in Phoenix, child welfare investigations are a constant threat

- The ‘death penalty’ of child welfare: In 6 months, some parents lose their children forever.

In a yearlong investigation, ProPublica and NBC News are examining the extraordinary reach of America’s child welfare system and its disproportionate impact on the lives of low-income families of color. The stream of reports generated by mandatory reporting is so vast, and so unevenly applied, public health and social work researchers estimate that more than half of all Black children nationally will have been the subject of a child protective services investigation by the time they turn 18 — nearly double the rate of white children.

After a hotline report comes in, it’s the job of child welfare investigators to determine whether a child is truly in danger. These caseworkers aren’t held to the same legal or training standards as law enforcement, but they can wield significant power, ProPublica and NBC News found, sometimes pressuring their way into homes without court orders to comb through closets and pantries, looking for signs of what’s lacking.

Under this system, child welfare agencies investigate the families of 3.5 million children each year and take about 250,000 kids into protective custody, according to federal data. Fewer than 1 in 5 of these family separations are related to allegations of physical or sexual abuse, the original impetus behind mandatory reporting. Instead, the vast majority of removals are based on reports of child neglect, a broad range of allegations often tied to inadequate housing or a parent’s drug addiction.

In response, a growing movement of family lawyers, researchers and child welfare reform advocates have called for a radical change in the approach to child protection in America, starting with the abolition of mandatory reporting. This idea has grown in popularity among both progressive activists and conservatives who oppose what they call excessive government intrusion in the lives of families. Other critics support less dramatic reforms, such as limiting which professionals are required to report and providing better training for mandated reporters.

The fallout from Pennsylvania’s expansion of mandatory reporting has become something of a cautionary tale among those calling for a system overhaul. Even some proponents of the changes have begun to question their impact.

State Rep. Todd Stephens, a Republican who helped spearhead the post-Sandusky reforms, said the impact of the changes warranted closer examination. In response to NBC News and ProPublica’s findings, he said he would lead a legislative effort to take a “deep dive in the data” to ensure the laws are protecting children as intended.

But Stephens said he believes the legislation is working, citing the massive increase in hotline reports and the 6,000 additional children with substantiated findings of abuse or serious neglect over five years.

“The goal was, if people thought children were in trouble or in danger, we wanted the cavalry to come running,” Stephens said. “That’s 6,000 kids who are getting help who might not have otherwise.”

Child welfare experts, however, cautioned against drawing conclusions based on the increase in substantiated abuse cases because those are subjective determinations made by caseworkers that children were more likely than not to be at risk of being abused and do not indicate whether the findings were ultimately dismissed by a judge.

Dr. Rachel Berger, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh who served on a task force that paved the way for the 2014 reforms , said the state has not produced evidence to show the changes have made children safer.

In 2020, while testifying before the Pennsylvania House of Representatives , Berger warned lawmakers that the reforms “may have inadvertently made children less safe” by straining the system and siphoning resources away from genuine cases of abuse.

“We are continuing to tell mandated reporters, ‘Report, report, report,’ and nobody can handle it,” Berger said in an interview.

Jon Rubin, deputy secretary at the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services’ Office of Children, Youth and Families, which oversees the state’s ChildLine call center, said it’s “really hard to evaluate” whether the 2014 reforms succeeded in making children safer overall. Rubin said he’s aware of the concern that the changes overwhelmed the system and may have contributed to the increase in child abuse deaths. But he cautioned against drawing conclusions without considering other factors, such as the strain on the system caused by the fentanyl epidemic beginning in 2017.

Rubin said his agency is studying ways to reduce the number of hotline reports related to poverty and housing issues, in part by encouraging mandatory reporters to instead connect families directly with resources. The state has also made it a priority to keep struggling families together by providing access to services such as mental health counseling and parental support groups, Rubin said. He worries about the potential impact of more dramatic changes.

“How many children’s lives are we willing to risk to, as you said, abolish the system, to reduce the overreporting risk?” Rubin said. Would preventing unnecessary reports, he asked, be worth “one more child hurt or killed, five more children hurt or killed, 100 more children hurt or killed?”

But Richard Wexler, the executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, a Virginia-based advocacy group, said that this logic ignores the harm that comes with unnecessary government intrusion in the lives of innocent families. Simply having an investigation opened can be traumatic, experts say, and numerous studies show that separating young children from their parents leads to increased risk of depression , developmental delays, attachment issues and post-traumatic stress disorder.

It isn’t necessary to threaten educators, social workers, doctors and other professionals with criminal charges in order to protect children, Wexler argued.

“Abolishing mandatory reporting does not mean abolishing reporting,” he said. “Anybody can still call ChildLine. What it does, however, is put the decision back in the hands of professionals to exercise their judgment concerning when to pick up the phone.”

The cost of seeking help

April Lee, a Black mother of three in Philadelphia, said she has seen and experienced firsthand the way mandatory reporting and the prospect of child removals create a culture of fear in low-income communities.

In Philadelphia, the state’s most populous city, Black children were the focus of about 66% of reports to the city’s Department of Human Services, its child welfare agency, even though they make up about 42% of the child population, according to a 2020 report commissioned by the department.

Over time, Lee said, moms in neighborhoods like hers get used to having child welfare agents show up on their steps.

“It’s a shame,” she said. “You get to the point where it’s almost normalized that you’re going to have that knock on your door.”

Lee estimates that she’s personally had about 20 such reports filed against her in the two decades since she gave birth to her first child at the age of 15. In most instances, she said, the caseworkers didn’t leave her with paperwork, but she said the accusations ranged from inadequate housing to concerns over her son’s scraped knee after a tumble on the front porch.

The agency never discloses who files the reports, but Lee believes it was a call from a mandatory reporter that triggered the investigation that resulted in her children being taken away. In 2013, a year after the birth of her third child, Lee said, she was drugged at a bar and raped. In her struggle to cope with the trauma, she said, she confided in a doctor.

“I was honest,” Lee said. “Like ‘I’m f---ing struggling. I’m struggling emotionally.’”

She suspects someone at the clinic where she sought mental health care made the hotline call, most likely, she said, believing that the city’s child welfare agency would be able to help.

The agency opened an investigation and determined that Lee — who at one point had left her three children with a friend for several days — was not adequately caring for her children. The agency took them into protective custody, according to court records reviewed by NBC News and ProPublica. Afterward, Lee said, she spiraled into drug addiction and homelessness.

At her lowest point, Lee slept on a piece of cardboard in the Kensington neighborhood, the epicenter of Philadelphia’s opioid crisis. It took two years to get clean, she said, and another three before she regained custody of all of her children.

Lee said people like to tell her she’s proof that the system works, but she disagrees.

“My children still have deficits to this day due to that separation,” she said. “I still have deficits to this day due to that separation. I still hold my breath at certain door knocks. That separation anxiety is still alive and well in my family.”

Now Lee works as a client liaison at Community Legal Services, guiding parents through the system. The job is funded by a grant from the city agency that took her children. Virtually all of the mothers she works with have one thing in common, she said: They’re struggling to make ends meet.

“We see that in a lot of our cases,” Lee said. “You have someone that went to their doctor to say, ‘Hey, I relapsed.’ That’s a call to the ChildLine. Or you have a family that might go into a resource center saying, ‘Hey, we’re homeless.’ That’s a call to the ChildLine. You have children that show up to school without proper clothing. That’s a call to the ChildLine.”

But mandatory reporting, and the fear that it provokes, makes it harder for them to get the help they need.

“The solution to poverty,” Lee said, “should not be the removal of your children.”

Policies driven by outrage

In 1962, a pediatrician named C. Henry Kempe published a seminal paper identifying a new medical condition that he called “the battered-child syndrome.” Drawing on a survey of hospital reports nationwide and a review of medical records, Kempe warned that physical abuse had become a “significant cause of childhood disability and death” in America and that this violence often went unreported.

The paper led to widespread media attention and calls to address what some experts began calling the nation’s hidden child abuse epidemic. In the rush to take action, one solution emerged above all else: mandatory reporting.

Within four years of Kempe’s paper, every state had passed some form of mandatory child abuse reporting. In 1974, despite a lack of research into the effects of these new policies, the approach was codified into federal law when Congress enacted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which requires states to have mandatory reporting provisions in order to receive federal grants for preventing child abuse.

It became conventional wisdom among child welfare policymakers that more reporting and investigations would make children safer. States gradually expanded reporting requirements in the decades that followed, adding ever more professionals — including animal control officers, computer technicians and dentists — to the list. They also expanded the definition of child maltreatment to include emotional abuse and neglect.

But critics say these policy decisions too often have been guided by public outrage and politics, not by data and research.

“Reporting has been our one response to concerns about child abuse,” said Dr. Mical Raz, a physician and professor of history at the University of Rochester who has studied the impact of mandatory child abuse reporting. “Now we have quite a bit of data that shows that more reporting doesn’t result in better identification of children at risk and is not associated with better outcomes for children, and in some cases may cause harm to families and communities.”

The Sandusky scandal, Raz said, demonstrates how a high-profile atrocity and public outcry can drive policy decisions.

The longtime Penn State assistant football coach was convicted in 2012 on 45 counts of child sexual abuse tied to the repeated rape and molestation of boys over a 15-year period. An investigation commissioned by the Penn State Board of Trustees found that several university officials, including legendary Nittany Lions football coach Joe Paterno, had known about allegations of sex abuse against Sandusky as early as 1998, but had shown a “total and consistent disregard” for “the safety and welfare of Sandusky’s child victims.”

In response, Pennsylvania passed a raft of reforms. It clarified and expanded the definition of abuse and added tens of thousands of additional people to the state’s roster of mandated reporters — which now includes virtually any adult who works or volunteers with children. It also increased the criminal consequences for failing to report child abuse, with penalties ranging from a misdemeanor to a second-degree felony, punishable by up to 10 years in prison. Although such prosecutions are rare, child welfare officials said the threat is effective in driving more professionals to report.

But the state failed to include additional funding to handle the anticipated increase in hotline calls and investigations, despite warnings from county officials that the reforms “were going to put a massive strain on their workers and would require additional resources,” according to a 2017 report from the state auditor general.

Those warnings proved prescient. In early 2015, after the changes went into effect and thousands of additional reports flooded Pennsylvania’s child abuse hotline, state officials estimated 4 in 10 callers were placed on hold for so long that they hung up before getting a caseworker on the line.

Some ChildLine workers reported an uptick in calls from mandated reporters who openly acknowledged they did not really believe that a child was in danger. Haven Evans, now the director of programs at Pennsylvania Family Support Alliance, which trains mandatory reporters across the state, was working at the state’s hotline center that year.

“There were a lot of mandatory reporters who would even admit on the phone call that they were making this report because they were concerned with the changes in the law and the penalties being increased,” Evans said. “They just wanted to, for lack of a better word, cover their butt.”

In the months and years that followed, the state added funding and workers and upgraded call center technology to keep up with the deluge. But taking a report is just the first step of the process — what some refer to as the child welfare system’s “front door” — and not enough attention has been paid to studying whether the system as a whole leads to better outcomes, said Cathleen Palm, founder of the Center for Children’s Justice, a nonprofit in Bernville, Pennsylvania, that advocates for government interventions to protect children.

In 2018, Palm came out against proposed legislation to further expand mandatory reporting that had been introduced in the wake of the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal and grand jury investigation. Even though Palm is herself a survivor of child sexual abuse, her calls for a formal study before passing more reforms made her a target of attacks, she said.

“I literally got called by a senior official at the attorney general’s office, who called me screaming at me, equating me to a friend of the pedophile,” Palm said. “I was floored. Do you have any sense of who you’re talking to?”

The following year, state lawmakers acted anyway, passing a law that expanded when failure to report is a felony .

The same dynamic has played out across the country: High-profile media coverage of child abuse deaths and child sexual abuse have created overwhelming political pressure to ramp up mandatory reporting, in red and blue states alike.

Eighteen states have gone so far as to implement universal child abuse reporting requirements , deputizing every adult in the state as a mandatory reporter. But a 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that universal reporting requirements led to more unfounded reports while failing to detect additional confirmed cases of child maltreatment.

Kelley Fong, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Irvine, has done extensive research into the impacts of mandatory reporting policies. When Fong interviewed dozens of impoverished mothers in Rhode Island and later Connecticut , they described how mandated reporters are “omnipresent” and how the fear of a call to Child Protective Services leads some to avoid seeking public assistance.

But when she spoke to professionals who had filed reports against parents, Fong found a disconnect.

“Almost to a person, every single mandated reporter said, ‘I reported because I wanted to help the family,’” Fong said. “For the most part, these mandated reporters are in their jobs because they want to help people, they want to improve conditions for children and families. And so here is this agency that offers them this possibility of getting help to parents and children.”

Fong compared this approach to sending armed police officers to assist people struggling with homelessness, mental illness and addiction — a practice that’s drawn increased scrutiny since 2020’s nationwide demonstrations for racial justice and police reform. But while there’s growing awareness of the consequences of what activists view as the overpolicing of Black communities, Fong said fewer people have applied that same critical lens to child welfare.

That’s starting to change.

In 2019, in response to concerns that Massachusetts wasn’t doing enough to protect children, the state legislature voted to create a special commission to study how best to expand mandatory reporting requirements. For two years, the commission was progressing toward that goal — until they agreed to hear public comments on their plans.

During four hours of virtual testimony in April 2021, the commission heard from dozens of parents, social workers, legal experts and reform activists, most of whom expressed deep concerns about the potential harms of expanded reporting requirements. Raz was among those who testified, citing as a warning the dysfunction that followed the Pennsylvania reforms.

Afterward, members of the commission said they were “shocked” and “taken aback” to learn about potential problems associated with expanding the child welfare system. As a result, when the commission delivered its final report to lawmakers in June 2021, it made no formal policy recommendations.

Instead, it called for further study of the unintended impacts of mandatory reporting.

The strain on Philadelphia’s system

Few places were harder hit by Pennsylvania’s surge of new child abuse reports after 2015 than Philadelphia.

Kimberly Ali, commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Human Services, the city’s child welfare agency, acknowledged in an interview with NBC News that the change in the state’s mandatory reporting policies put a strain on Philadelphia’s system. She said the local hotline managed by her department “imploded” after the Sandusky reforms. It took the agency years to recover.

“That was a difficult time at the Department of Human Services, just trying to manage the number of calls and the number of investigations,” Ali said.

In a city where nearly a quarter of residents live in poverty, the deluge of new reports disproportionately involved Black families and led to a sharp increase in the number of Philadelphia children being taken from their parents. In 2017, the city’s child welfare agency removed the most children per capita among the 10 largest cities in the U.S. — at three times the rate of New York and four times that of Chicago, according to data compiled by the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

Five of those children belonged to Lisa Mothee.

On Aug. 21, 2017, a mandatory reporter employed by the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia called in a hotline report flagging that Mothee’s newborn baby had tested positive for opioids. The hospital later reported that Mothee had also failed to provide her baby with proper medical care, because she declined vaccinations and other medical screenings typically provided to newborns, according to court records.

At a court hearing a month later, Mothee, who is Black, told a judge that she had taken a Percocet to cope with pain late in her pregnancy. She explained that she’d stopped consenting to vaccines after one of her children had an adverse reaction several years earlier, which she believed was her right as a parent. After a lawyer for the city’s child welfare agency acknowledged in court that they didn’t have reason to believe Mothee’s children were in danger, she figured the case would be dismissed.

Instead, the judge ordered Mothee and the father of four of her children to be handcuffed and held in court for several hours while child protection agents picked up all five of her kids from school and a babysitter.

“What? No!” Mothee called out, according to a court transcript. “You can’t take my kids! You can’t take my kids!”

Eight months would pass before a different judge ordered her children to be returned . Years later, Mothee said she’s still struggling with the trauma of the ordeal. “It’s like a death,” she said. “You never get over that feeling.”

Mothee’s case was part of a statewide trend post-Sandusky.

The number of Pennsylvania children reported as possible victims of serious medical neglect — a blanket term describing a parent’s failure to provide adequate medical care — nearly quadrupled after the reforms went into effect in 2015, triggering Child Protective Services investigations into the well-being of about 9,600 children over a five-year span, according to the ProPublica and NBC News analysis of federal data.

This surge followed a change in how the state defined when neglect, including medical neglect, can be considered a form of child abuse. Lawmakers lowered the threshold from any failure to care for a child that endangers their “life or development,” to any failure that “threatens a child’s well-being.” Critics say the change has usurped parents’ right to make medical decisions for their children and has punished people who lack easy and affordable access to health care.

Mothee’s case was among several cited in a scathing report issued in April by a special committee of the Philadelphia City Council that detailed the unintended consequences of mandatory child abuse reporting and alleged failures at Philadelphia’s child welfare agency.

City Councilmember David Oh pushed for the creation of the special committee after his own brush with a mandatory reporter in 2018. A hospital worker at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia had phoned in a hotline report after Oh, a Republican and the city’s first Asian-American councilmember, brought his son to the emergency room with a broken collarbone. Oh explained that his boy had been injured while practicing martial arts, but the hospital social worker said she had no choice but to notify the city, triggering what Oh viewed as a senseless investigation into a report that was ultimately deemed unfounded.

Afterward, Oh said, he heard from dozens of Philadelphia parents, including Mothee, who’d gone through similar ordeals.

Ali, the DHS commissioner, said her agency has reduced the city’s foster care rolls by about 29% since 2017, with an increased focus on providing families with services rather than removing children. But Oh said not enough has been done to mitigate the fear created by mandatory reporting, especially in poorer Black communities.

“In those neighborhoods, everyone knows about mandated reporters,” Oh said during an interview at his office. “So when your child falls off a bike, you’ve got to think, ‘Do we take him to the hospital or not?’”

Oh’s committee made several recommendations for reforms — including a call for the state to abolish mandatory reporting.

“They have a system where everyone pulls a fire alarm anytime they feel like there’s a potential for fire, and theoretically it’s great because we’re going to catch every fire before it begins,” Oh said. “But how it’s worked out is all our firefighters are running around to false alarms, and now buildings are burning and people are dying. It’s a bad system.”

'Mandatory reporters into mandatory supporters'

Some experts argue that the best way to reduce unfounded reports of child abuse and neglect is not by abolishing mandatory reporting, but by doing a better job of training professionals on when to report — and when it’s better to provide help to a family in need instead.

In Pennsylvania, medical professionals are required to complete a two-hour mandatory reporter training course every two years; other professionals must take a three-hour training every five years.

But Dr. Benjamin Levi, a pediatrician and former director of the Center for the Protection of Children, a research and policy group at Penn State Children’s Hospital, said such training programs typically lack a clear explanation of the “reasonable suspicion” of abuse that should trigger a report.

“‘Reasonable suspicion’ is a feeling — they don’t even define it,” said Levi, who developed an alternative training for mandatory reporters to help fill in the gaps.

“If you increase mandated reporting, and you don’t make sure that mandated reporters know what to report and what not to report, you’ve just made the problem worse.”

Educators, the largest source of child abuse reports nationally, in particular have struggled to correctly identify children in need of help. From 2015 to 2019 in Pennsylvania, 24 out of 25 children referred to Child Protective Services by education professionals had their cases dismissed by case workers as unsubstantiated — but only after children and parents had been subjected to questioning and home searches.

Ali, the head of the Philadelphia child welfare agency, said her department has heard from educators who felt unable to help struggling families because they feared potential criminal charges for not reporting to the abuse hotline. With the support of a federal grant, her department plans to create an alternative hotline that mandatory reporters can call when they believe a family is in need but don’t suspect children are in danger.

Adopting the language of reform activists, Ali said the goal is “turning mandatory reporters into mandatory supporters.”

But Benita Williams, former operations director of Philadelphia’s child welfare agency, warned against more radical change, stressing that mandatory reporters should never hesitate to make a report in cases of suspected child abuse.

“Just report,” said Williams, now executive director of the Philadelphia Children’s Alliance, which supports victims of child sexual abuse. “If you are not sure, report and let the professional screen that out. Don’t try to become a social worker.”

Phoebe Jones, who helps lead DHS-Give Us Back Our Children, a group that advocates on behalf of Philadelphia mothers and grandmothers who’ve had children taken from them for issues related to poverty and domestic violence, argues that the real solution is to address the issues underlying most ChildLine reports, by providing parents and caregivers with a universal basic income to ensure they have what they need to care for children.

“Rather than taking children from their mothers and paying foster parents to care for them,” Jones said, “why don’t we invest that money in families?”

Mike Hixenbaugh reported from Philadelphia; Suzy Khimm reported from Washington, D.C.; Agnel Philip reported from New York.

Mike Hixenbaugh is a senior investigative reporter for NBC News, based in Maryland.

Suzy Khimm is a national investigative reporter for NBC News based in Washington, D.C.

Agnel Philip is a data reporter for ProPublica.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Parenting, childcare and children's services

- Safeguarding and social care for children

- Safeguarding and child protection

- Preventing neglect, abuse and exploitation

Training resources on childhood neglect: family case studies

Case studies for training multi-agency groups on identifying and preventing child neglect.

F1.0: case studies - Evans family

PDF , 198 KB , 1 page

F1.1: Fiona Evans' story

PDF , 183 KB , 1 page

F1.2: Steve Evans' story

PDF , 291 KB , 1 page

F1.3: Liam Evans' story

PDF , 233 KB , 1 page

F1.4: Shireen Evans' story

PDF , 253 KB , 1 page

F1.5: Lewis Evans' story

F1.6: liam evans' history.

PDF , 206 KB , 1 page

F2.0: case studies - Henderson/Miller/Taylor family

PDF , 313 KB , 2 pages

F2.1: Claire Henderson's story

PDF , 277 KB , 1 page

F2.2: Darren Miller's story

PDF , 223 KB , 1 page

F2.3: Michelle Henderson's story

PDF , 255 KB , 1 page

F2.4: Troy Taylor's story

PDF , 241 KB , 1 page

F2.5: Susan Miller's story

PDF , 324 KB , 1 page

F2.6: Michelle Henderson's history

PDF , 288 KB , 1 page

F2.7: Michelle Henderson's chronology

PDF , 303 KB , 2 pages

F2.8: Troy Taylor's history

PDF , 267 KB , 1 page

F3.0: case studies - Akhtar family

PDF , 141 KB , 2 pages

F3.1: Mabina Akhtar's story

PDF , 164 KB , 1 page

F3.2: Saleem Akhtar's story

PDF , 168 KB , 1 page

F3.3: Wasim Akhtar's story

PDF , 152 KB , 1 page

We have developed 3 family case studies to illustrate many of the issues that practitioners are likely to encounter when investigating childhood neglect. The 3 families are:

- Henderson/Taylor/Miller

The case studies provide first person narratives giving the perspective of each adult and child.

Accompanying videos to these case studies are available on our YouTube channel.

The guidance and exercise documents , presentations and notes and handouts that complement these family case studies are also available.

Related content

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Take action

- Report an antitrust violation

- File adjudicative documents

- Find banned debt collectors

- View competition guidance

- Competition Matters Blog

New HSR thresholds and filing fees for 2024

View all Competition Matters Blog posts

We work to advance government policies that protect consumers and promote competition.

View Policy

Search or browse the Legal Library

Find legal resources and guidance to understand your business responsibilities and comply with the law.

Browse legal resources

- Find policy statements

- Submit a public comment

Vision and Priorities

Memo from Chair Lina M. Khan to commission staff and commissioners regarding the vision and priorities for the FTC.

Technology Blog

Consumer facing applications: a quote book from the tech summit on ai.

View all Technology Blog posts

Advice and Guidance

Learn more about your rights as a consumer and how to spot and avoid scams. Find the resources you need to understand how consumer protection law impacts your business.

- Report fraud

- Report identity theft

- Register for Do Not Call

- Sign up for consumer alerts

- Get Business Blog updates

- Get your free credit report

- Find refund cases

- Order bulk publications

- Consumer Advice

- Shopping and Donating

- Credit, Loans, and Debt

- Jobs and Making Money

- Unwanted Calls, Emails, and Texts

- Identity Theft and Online Security

- Business Guidance

- Advertising and Marketing

- Credit and Finance

- Privacy and Security

- By Industry

- For Small Businesses

- Browse Business Guidance Resources

- Business Blog

Servicemembers: Your tool for financial readiness

Visit militaryconsumer.gov

Get consumer protection basics, plain and simple

Visit consumer.gov

Learn how the FTC protects free enterprise and consumers

Visit Competition Counts

Looking for competition guidance?

- Competition Guidance

News and Events

Latest news, betterhelp customers will begin receiving notices about refunds related to a 2023 privacy settlement with ftc.

View News and Events

Upcoming Event

Older adults and fraud: what you need to know.

View more Events

Sign up for the latest news

Follow us on social media

--> --> --> --> -->

Playing it Safe: Explore the FTC's Top Video Game Cases

Learn about the FTC's notable video game cases and what our agency is doing to keep the public safe.

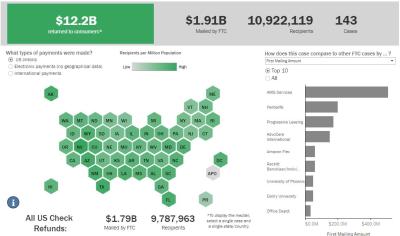

Latest Data Visualization

FTC Refunds to Consumers

Explore refund statistics including where refunds were sent and the dollar amounts refunded with this visualization.

About the FTC

Our mission is protecting the public from deceptive or unfair business practices and from unfair methods of competition through law enforcement, advocacy, research, and education.

Learn more about the FTC

Meet the Chair

Lina M. Khan was sworn in as Chair of the Federal Trade Commission on June 15, 2021.

Chair Lina M. Khan

Looking for legal documents or records? Search the Legal Library instead.

- Cases and Proceedings

- Premerger Notification Program

- Merger Review

- Anticompetitive Practices

- Competition and Consumer Protection Guidance Documents

- Warning Letters

- Consumer Sentinel Network

- Criminal Liaison Unit

- FTC Refund Programs

- Notices of Penalty Offenses

- Advocacy and Research

- Advisory Opinions

- Cooperation Agreements

- Federal Register Notices

- Public Comments

- Policy Statements

- International

- Office of Technology Blog

- Military Consumer

- Consumer.gov

- Bulk Publications

- Data and Visualizations

- Stay Connected

- Commissioners and Staff

- Bureaus and Offices

- Budget and Strategy

- Office of Inspector General

- Careers at the FTC

Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule ("COPPA")

- Consumer Protection

- Children's Privacy

COPPA imposes certain requirements on operators of websites or online services directed to children under 13 years of age, and on operators of other websites or online services that have actual knowledge that they are collecting personal information online from a child under 13 years of age.

File Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule: Final Rule Amendments (587.08 KB)

- Agency Information Collection Activities; Proposed Collection; Comment Request (COPPA Rule) ( October 2, 2018 )

- 16 CFR Part 312: Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule Safe Harbor Proposed Self-Regulatory Guidelines; Entertainment Software Rating Board’s COPPA Safe Harbor Program Application to Modify Program Requirements Federal Register Notice ( April 5, 2018 )

- 16 CFR Part 312: Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule Proposed Parental Consent Method; Jest8 Limited, Trading as Riyo, Application for Approval of Parental Consent Method ( August 7, 2015 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule: Final Rule Amendments To Clarify the Scope of the Rule and Strengthen Its Protections For Children's Personal Information; 16 C.F.R. Part 312 ( January 17, 2013 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule: Supplemental Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Request For Comment - Proposal To Modify Certain Proposed Definitions, 16 C.F.R. Part 312 ( August 6, 2012 )

- 16 C.F.R. Part 312: Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule: Proposed Rule; Request for Comment on Proposal to Amend Rule to Respond to Changes in Online Technology ( September 27, 2011 )

- Request for Public Comment on the Federal Trade Commission's Implementation of the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( April 5, 2010 )

- Request for Public Comment on the Federal Trade Commission's Implementation of the Rule, 75 FR 17089 ( April 5, 2010 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( April 22, 2005 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule: Request for Comments - 16 CFR Part 312 ( April 22, 2005 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( January 14, 2005 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( April 17, 2002 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( November 3, 1999 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( July 27, 1999 )

- Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule - 16 CFR Part 312 ( April 27, 1999 )

- FTC Extends Deadline for Comments on COPPA Rule until December 11 (December 9, 2019)

- FTC Extends Deadline for Comments on COPPA Rule until December 9 (October 17, 2019)

- FTC Seeks Comments on Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act Rule (July 25, 2019)

- FTC Seeks Comment on Proposed Modifications to Video Game Industry Self-Regulatory Program Approved under the COPPA Safe Harbor Program (April 2, 2018)

- FTC Seeks Public Comment on Riyo Proposal for Parental Verification Method Under COPPA Rule (July 31, 2015)

- FTC Approves iKeepSafe COPPA “Safe Harbor” Oversight Program (August 6, 2014)

- FTC Files Amicus Brief Clarifying Role of Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (March 21, 2014)

- FTC Seeks Public Comment on iKeepSafe’s Proposed Safe Harbor Program Under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (March 13, 2014)

- FTC Concludes Review of iVeriFly’s Proposed COPPA Verifiable Parental Consent Method (February 25, 2014)

- FTC Approves kidSAFE Safe Harbor Program (February 12, 2014)

- FTC’s ‘Net Cetera’ Advises Parents on How to Talk to Their Kids About Internet Use (January 28, 2014)

- FTC Grants Approval for New COPPA Verifiable Parental Consent Method (December 23, 2013)

- FTC Denies AssertID's Application for Proposed COPPA Verifiable Parental Consent Method (November 13, 2013)

- FTC Seeks Public Comment on kidSAFE’s Proposed Safe Harbor Program Under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (September 16, 2013)

- FTC Strengthens Kids' Privacy, Gives Parents Greater Control Over Their Information By Amending Childrens Online Privacy Protection Rule (December 19, 2012)

- FTC Seeks Comments on Additional Proposed Revisions to Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule (August 1, 2012)

- FTC Extends Deadline for Comments on Proposed Amendments to the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule Until December 23 (November 18, 2011)

- FTC Seeks Comment on Proposed Revisions to Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule (September 15, 2011)

- FTC Extends Public Comment Period for COPPA Rule Review until July 12, 2010 (July 2, 2010)

- FTC to Host Public Roundtable to Review Whether Technology Changes Warrant Changes to the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule (April 19, 2010)

- FTC Seeks Comment on Children's Online Privacy Protections; Questions Whether Changes to Technology Warrant Changes to Agency Rule (March 24, 2010)

- FTC Retains Children's Online Privacy Protection (COPPA) Rule Without Changes (March 8, 2006)

- FTC Seeks Comment on Children's Online Privacy Rule (April 21, 2005)

- FTC Seeks Comment on Proposed COPPA Rule Amendment (January 12, 2005)

- FTC Protecting Children's Privacy Online (April 22, 2002)

- New Rule Will Protect Privacy of Children Online (October 20, 1999)

- FTC to Hold Public Workshop on Appropriate Methods to Obtain Parental Consent in Conjunction with Rulemaking on Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (June 23, 1999)

- Children's Online Privacy Proposed Rule Issued by FTC (April 20, 1999)

- The Future of the COPPA Rule: An FTC Workshop ( July 16, 2019 )

- Protecting Kids' Privacy Online: Reviewing the COPPA Rule ( June 2, 2010 )

File Protecting Children’s Privacy Under COPPA: A Survey on Compliance (1.22 MB)

File Summary of Ex Parte Communication on December 10, 2019, with Commissioner Christine S. Wilson; Forrest Waldron, KreekCraft; and Travis Richardson, Ellify Talent Agency, Regarding the 2019 COPPA Rule Review (92.73 KB)

File Summary of Ex Parte Communication on December 16, 2019, between Commissioner Christine S. Wilson and Mohamed Moshyem, regarding the 2019 COPPA Rule Review (94.72 KB)

File Summary of Ex Parte Communication on December 9, 2019, between Commissioner Christine S. Wilson and Representatives from the DanTDM YouTube channel, regarding the 2019 COPPA Rule Review (94.88 KB)

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Protecting the young and vulnerable: Family & Youth’s Children’s Advocacy Center stands as a champion for children

Published 12:57 pm Sunday, April 28, 2024

By Crystal Stevenson

April is Child Abuse Prevention Month and experts at Family & Youth are using this time as an opportunity to stress the importance of families and communities working together to prevent child abuse and neglect.

“We have to create awareness in order for the community to understand that there is an issue that’s happening,” said Patra Minix, director of the Children’s Advocacy Center. “Child abuse happens in all communities, every socio-economic status and in people with different backgrounds. People need to become aware not only to be able to recognize it but prevent it. That’s what we do.”

Family & Youth, established as a non-profit organization in 1970, is an umbrella organization that provides professional family services in Southwest Louisiana. Eight agencies work under that umbrella — Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA), Human Services Response Institute, Children’s Advocacy Center (CAC), Performance Employee Assistance and Business Services , Children & Families Action Network, Autism Support Alliance and The Leadership Center for Youth .

Email newsletter signup

“We serve everyone in our community, but we have a very heavy focus on our most vulnerable kids — those who have been abused or neglected,” said Michaelynn Parks, vice president of the organization. “We are those front-line people who get to be part of their lives in their most vulnerable moments.”

Minix said awareness is essential in preventing child abuse.

“There are many different indicators and, of course, it’s going to be case-specific and different for each child but a few that we see across the board are unexplained injuries — if a child has an injury and they’re unable to tell you how they received the injury — also any changes in a child’s pattern — eating, sleeping, school performance, or maybe potty training regression — and any changes in a child’s behavior.”

Minix, who trained as a CASA volunteer while in college, said she “absolutely loves children.”

“I love to serve in any capacity I’m able to serve my community and help children,” she said. “I remember taking the tour of the CAC my sophomore year and I remember seeing myself in the investigative chair and then four years later is when I started here.”

Minix said their team goes out into the community to talk about child abuse, how to recognize it and tools to prevent it. One of those tools is encouraging parents to teach the importance of body safety in an age-appropriate manner, particularly teaching children the correct anatomical names.

“It reduces that stigma that’s associated with it and it empowers the child,” she said.

Another tool is Internet safety.

“We have to monitor everything that our children are engaging in online — whether it’s a video game, their smart devices,” Minix said. “They’re interacting with the world so we want to make sure that we are monitoring that. Also, form connections and a trusting bond with your child. That is what is going to reduce their risk of being abused by a perpetrator.

The CAC, which is separate from the main Family & Youth building to main confidentiality, is designed to coordinate services for children who have been reported as sexually or severely physically abused.

Minix said the CAC provides a comfortable environment and well-trained staff who work together with area prosecutors, law enforcement agencies, child protection investigators, social service workers, therapists, victims’ advocates and medical professionals to investigate child abuse allegations and reduce the number of investigative interviews typically experienced by young victims.

“All of the interviews are recorded so that the child does not have to keep retelling their experience over and over again,” Minix said. “These interviews are fact-finding and non-leading and are used strictly for investigative purposes. We receive our referrals from child protection and law enforcement as well adult protective services, because we are trained to interviewed mentally delayed adults.”

They’re also trained to interview non-verbal children as well as those who are hearing-Impaired.

“As soon as they enter the door, the interview process begins,” she said. “We make sure to welcome them with a warm welcome and a snack or treats and we’ve partnered with Doctor Dogs so therapy dogs can come in to really reduce the stress of being in a new environment to come and tell about what they experienced.”

At the end of the interview, the child gets to choose a treat from the prize closet so the session ends on a positive note.

CASA Volunteers needed

Last year, the CAC conducted 592 interviews with children.

Parks said for community members with a heart for helping kids, CASA is in need of volunteers.

“We train them to advocate in the best interest of the child,” she said. “Oftentimes CAC is involved at the very beginning of a case when maybe there has been an allegation of abuse and neglect and they help law enforcement for the investigative piece, but after that a lot of times children enter into foster care and that’s where CASA comes into play.”

The CASA volunteer follows the child for the life of their case, ensuring they have everything they need to build resilience. Volunteers must be at least 21, pass a background check and have a heart to help.

All of the training is provided by Family & Youth.

“The volunteer would meet with the child at least once or twice a month, really connecting with them and creating that bond to help build resilience,” Parks said. “They also create court reports about every six months and give recommendations based on their fact-finding observations.

There are 27 CASA volunteers serving about 50 children in Calcasieu, Allen and Jeff Davis parishes. Nearly 120 children are still waiting to be assigned a volunteer. The majority of them are involved in neglect cases.

“If you’re wanting to give back, CASA is an amazing place to start,” Parks said. “We’re always in need of volunteers, especially those kids who are waiting for a voice. CASA gives hope to a lot of those kids — having a consistent person in their life who can help build that resiliency.”

Featured Local Savings

More local news.

Current, past educators in Welsh honored

BREAKING: Elton voters recall their mayor

Special School Board meeting set for April 30 to review April 10 weather event

SW La. school lunch menus April 29-May 3

Special sections.

- Small Business

- Jobs/Recruiting

- Celebrations

- Subscriptionss

- © 2024, American Press

PROTECTION OF CHILD LABOUR IN INDIA

AUTHOR – SUDHANSHU RAJ 1 & MRS.ADYA PANDEY 2 , STUDENT 1 AND ASSISTANT PROFESSOR 2 AT AMITY UNIVERSITY LUCKNOW UTTAR PRADESH

BEST CITATION – SUDHANSHU RAJ & MRS.ADYA PANDEY, PROTECTION OF CHILD LABOUR IN INDIA, INDIAN JOURNAL OF LEGAL REVIEW (IJLR) , 4 (1) OF 2024, PG. 1049-1057, APIS – 3920 – 0001 & ISSN – 2583-2344.

In the current situation, where international community does only grow, the unsolved problem of the childhood slavery is that you see kids working in industry. this essay argues that child labour problem is widely affected by social and economic factors. This piece of writing looks at an overall approach to the root causes shifting from addiction and poverty to illiteracy, lack of education, social and economic upturns and insufficient family income as the basic ones. Children cannot survive the financial hardships, they experience emotional issues being overly stressed, and they are at risk of getting wounded through working. At last, I believe the only reason why child labour was eradicated in our country, India (where governments has laws, governmental as well as non-governmental organizations have activities and communities had campaigns for the protection of child rights and to fight against child labour) was the role they all played. The more recent instances of weak supervisory authorities which have been unable to stop children from working disclose this aspect. The main purposes of any law pertaining to enabling children to work or involving any other forms of commitments by children to any form of employment or work have been to provide the working hours, minimum age of employment, complete physical wellness and general safety to the children. It is the much-awaited Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 which is by far the most important of the legislations that we have on child labour, the first one being the Child labour (Pledging of Labour) Act of 1933 and the second one being Employment of Child Act of 1986.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Child Protection Laws For most of American history, protecting and caring for children was considered a matter of state rather than federal concern. That changed beginning in 1980 when Congress enacted the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-272, 94 Stat. 500.

Some of the key rights and protections guaranteed to children through domestic and international laws include: Right to life, survival, and development. Right to identity and nationality from birth. Right to an adequate standard of living, including nutrition, shelter, healthcare. Right to be protected from abuse, harm, neglect, physical/mental ...

Child protection is a function of state government that is ruled by state law but supported by significant federal funding and-in. The Future of Children PROTECTING CHILDREN FROM ABUSE AND NEGLECT Vol. 8 * No. 1 - Spring 1998. 5. many states-carried out by local government entities. For simplicity, the.

Consider these three child safety measures. 1. Governance. The best way to take child protection seriously in your church is to start at the top: in your organization's leadership. As the Evangelical Council for Abuse Prevention's general counsel Sally Wagenmaker says, "Child Protection starts with good, godly governance.".