- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, creative problem solving as overcoming a misunderstanding.

- Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Solving or attempting to solve problems is the typical and, hence, general function of thought. A theory of problem solving must first explain how the problem is constituted, and then how the solution happens, but also how it happens that it is not solved; it must explain the correct answer and with the same means the failure. The identification of the way in which the problem is formatted should help to understand how the solution of the problems happens, but even before that, the source of the difficulty. Sometimes the difficulty lies in the calculation, the number of operations to be performed, and the quantity of data to be processed and remembered. There are, however, other problems – the insight problems – in which the difficulty does not lie so much in the complexity of the calculations, but in one or more critical points that are susceptible to misinterpretation , incompatible with the solution. In our view, the way of thinking involved in insight problem solving is very close to the process involved in the understanding of an utterance, when a misunderstanding occurs. In this case, a more appropriate meaning has to be selected to resolve the misunderstanding (the “impasse”), the default interpretation (the “fixation”) has to be dropped in order to “restructure.” to grasp another meaning which appears more relevant to the context and the speaker’s intention (the “aim of the task”). In this article we support our view with experimental evidence, focusing on how a misunderstanding is formed. We have studied a paradigmatic insight problem, an apparent trivial arithmetical task, the Ties problem. We also reviewed other classical insight problems, reconsidering in particular one of the most intriguing one, which at first sight appears impossible to solve, the Study Window problem. By identifying the problem knots that alter the aim of the task, the reformulation technique has made it possible to eliminate misunderstanding, without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. With the experimental versions of the problems exposed we have obtained a significant increase in correct answers. Studying how an insight problem is formed, and not just how it is solved, may well become an important topic in education. We focus on undergraduate students’ strategies and their errors while solving problems, and the specific cognitive processes involved in misunderstanding, which are crucial to better exploit what could be beneficial to reach the solution and to teach how to improve the ability to solve problems.

Introduction

“A problem arises when a living creature has a goal but does not know how this goal is to be reached. Whenever one cannot go from the given situation to the desired situation simply by action, then there has to be recourse to thinking. (…) Such thinking has the task of devising some action which may mediate between the existing and the desired situations.” ( Duncker, 1945 , p. 1). We agree with Duncker’s general description of every situation we call a problem: the problem solving activity takes a central role in the general function of thought, if not even identifies with it.

So far, psychologists have been mainly interested in the solution and the solvers. But the formation of the problem remained in the shadows.

Let’s consider for example the two fundamental theoretical approaches to the study of problem solving. “What questions should a theory of problem solving answer? First, it should predict the performance of a problem solver handling specified tasks. It should explain how human problem solving takes place: what processes are used, and what mechanisms perform these processes.” ( Newell et al., 1958 , p. 151). In turn, authors of different orientations indicate as central in their research “How does the solution arise from the problem situation? In what ways is the solution of a problem attained?” ( Duncker, 1945 , p. 1) or that of what happens when you solve a problem, when you suddenly see the point ( Wertheimer, 1959 ). It is obvious, and it was inevitable, that the formation of the problem would remain in the shadows.

A theory of problem solving must first explain how the problem is constituted, and then how the solution happens, but also how it happens that it is not solved; it must explain the correct answer and with the same means the failure. The identification of the way in which the problem is constituted – the formation of the problem – and the awareness that this moment is decisive for everything that follows imply that failures are considered in a new way, the study of which should help to understand how the solution of the problems happens, but even before that, the source of the difficulty.

Sometimes the difficulty lies in the calculation, the number of operations to be performed, and the quantity of data to be processed and remembered. Take the well-known problems studied by Simon, Crypto-arithmetic task, for example, or the Cannibals and Missionaries problem ( Simon, 1979 ). The difficulty in these problems lies in the complexity of the calculation which characterizes them. But, the text and the request of the problem is univocally understood by the experimenter and by the participant in both the explicit ( said )and implicit ( implied ) parts. 1 As Simon says, “Subjects do not initially choose deliberately among problem representations, but almost always adopt the representation suggested by the verbal problem statement” ( Kaplan and Simon, 1990 , p. 376). The verbal problem statement determines a problem representation, implicit presuppositions of which are shared by both.

There are, however, other problems where the usual (generalized) interpretation of the text of the problem (and/or the associated figure) prevents and does not allow a solution to be found, so that we are soon faced with an impasse. We’ll call this kind of problems insight problems . “In these cases, where the complexity of the calculations does not play a relevant part in the difficulty of the problem, a misunderstanding would appear to be a more appropriate abstract model than the labyrinth” ( Mosconi, 2016 , p. 356). Insight problems do not arise from a fortuitous misunderstanding, but from a deliberate violation of Gricean conversational rules, since the implicit layer of the discourse (the implied ) is not shared both by experimenter and participant. Take for example the problem of how to remove a one-hundred dollar bill without causing a pyramid balanced atop the bill to topple: “A giant inverted steel pyramid is perfectly balanced on its point. Any movement of the pyramid will cause it to topple over. Underneath the pyramid is a $100 bill. How would you remove the bill without disturbing the pyramid?” ( Schooler et al., 1993 , p. 183). The solution is burn or tear the dollar bill but people assume that the 100 dollar bill must not be damaged, but contrary to his assumption, this is in fact the solution. Obviously this is not a trivial error of understanding between the two parties, but rather a misunderstanding due to social conventions, and dictated by conversational rules. It is the essential condition for the forming of the problem and the experimenter has played on the very fact that the condition was not explicitly stated (see also Bulbrook, 1932 ).

When insight problems are used in research, it could be said that the researcher sets a trap, more or less intentionally, inducing an interpretation that appears to be pertinent to the data and to the text; this interpretation is adopted more or less automatically because it has been validated by use but the default interpretation does not support understanding, and misunderstanding is inevitable; as a result, sooner or later we come up against an impasse. The theory of misunderstanding is supported by experimental evidence obtained by Mosconi in his research on insight problem solving ( Mosconi, 1990 ), and by Bagassi and Macchi on problem solving, decision making and probabilistic reasoning ( Bagassi and Macchi, 2006 , 2016 ; Macchi and Bagassi, 2012 , 2014 , 2015 , 2020 ; Macchi, 1995 , 2000 ; Mosconi and Macchi, 2001 ; Politzer and Macchi, 2000 ).

The implication of the focus on problem forming for education is remarkable: everything we say generates a communicative and therefore interpretative context, which is given by cultural and social assumptions, default interpretations, and attribution of intention to the speaker. Since the text of the problem is expressed in natural language, it is affected, it shares the characteristics of the language itself. Natural language is ambiguous in itself, differently from specialized languages (i.e., logical and statistical ones), which presuppose a univocal, unambiguous interpretation. The understanding of what a speaker means requires a disambiguation process centered on the intention attribution.

Restructuring as Reinterpreting

Traditionally, according to the Gestaltists, finding the solution to an insight problem is an example of “productive thought.” In addition to the reproductive activities of thought, there are processes which create, “produce” that which does not yet exist. It is characterized by a switch in direction which occurs together with the transformation of the problem or a change in our understanding of an essential relationship. The famous “aha!” experience of genuine insight accompanies this change in representation, or restructuring. As Wertheimer says: “… Solution becomes possible only when the central features of the problem are clearly recognized, and paths to a possible approach emerge. Irrelevant features must be stripped away, core features must become salient, and some representation must be developed that accurately reflects how various parts of the problem fit together; relevant relations among parts, and between parts and whole, must be understood, must make sense” ( Wertheimer, 1985 , p. 23).

The restructuring process circumscribed by the Gestaltists to the representation of the perceptual stimulus is actually a general feature of every human cognitive activity and, in particular, of communicative interaction, which allows the understanding, the attribution of meaning, thus extending to the solution of verbal insight problems. In this sense, restructuring becomes a process of reinterpretation.

We are able to get out of the impasse by neglecting the default interpretation and looking for another one that is more pertinent to the situation and which helps us grasp the meaning that matches both the context and the speaker’s intention; this requires continuous adjustments until all makes sense.

In our perspective, this interpretative function is a characteristic inherent to all reasoning processes and is an adaptive characteristic of the human cognitive system in general ( Levinson, 1995 , 2013 ; Macchi and Bagassi, 2019 ; Mercier and Sperber, 2011 ; Sperber and Wilson, 1986/1995 ; Tomasello, 2009 ). It guarantees cognitive economy when meanings and relations are familiar, permitting recognition in a “blink of an eye.” This same process becomes much more arduous when meanings and relations are unfamiliar, obliging us to face the novel. When this happens, we have to come to terms with the fact that the usual, default interpretation will not work, and this is a necessary condition for exploring other ways of interpreting the situation. A restless, conscious and unconscious search for other possible relations between the parts and the whole ensues until everything falls into place and nothing is left unexplained, with an interpretative heuristic-type process. Indeed, the solution restructuring – is a re -interpretation of the relationship between the data and the aim of the task, a search for the appropriate meaning carried out at a deeper level, not by automaticity. If this is true, then a disambiguant reformulation of the problem that eliminates the trap into which the subject has fallen, should produce restructuring and the way to the solution.

Insight Problem Solving as the Overcoming of a Misunderstanding: The Effect of Reformulation

In this article we support our view with experimental evidence, focusing on how a misunderstanding is formed, and how a pragmatic reformulation of the problem, more relevant to the aim of the task, allows the text of the problem to be interpreted in accordance with the solution.

We consider two paradigmatic insight problems, the intriguing Study Window problem, which at first sight appears impossible to solve, and an apparent trivial arithmetical task, the Ties problem ( Mosconi and D’Urso, 1974 ).

The Study Window problem

The study window measures 1 m in height and 1 m wide. The owner decides to enlarge it and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to double the area of the window without changing its shape and so that it still measures 1 m by 1 m. The workman carried out the commission. How did he do it?

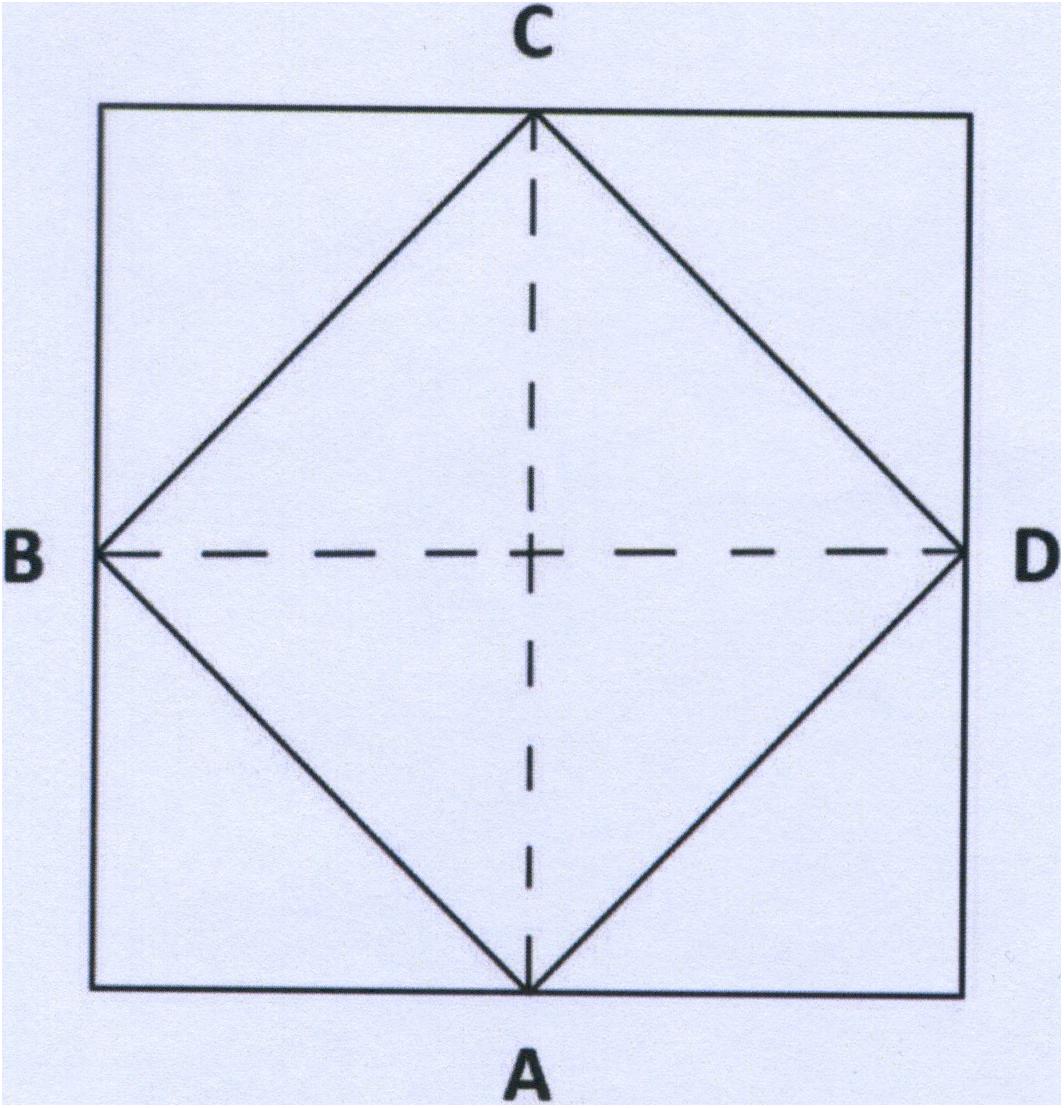

This problem was investigated in a previous study ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2015 ). For all the participants the problem appeared impossible to solve, and nobody actually solved it. The explanation we gave for the difficulty was the following: “The information provided regarding the dimensions brings a square form to mind. The problem solver interprets the window to be a square 1 m high by 1 m wide, resting on one side. Furthermore, the problem states “without changing its shape,” intending geometric shape of the two windows (square, independently of the orientation of the window), while the problem solver interprets this as meaning the phenomenic shape of the two windows (two squares with the same orthogonal orientation)” ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2015 , p. 156). And this is where the difficulty of the problem lies, in the mental representation of the window and the concurrent interpretation of the text of the problem. Actually, spatial orientation is a decisive factor in the perception of forms. “Two identical shapes seen from different orientations take on a different phenomenic identity” ( Mach, 1914 ).

The solution is to be found in a square (geometric form) that “rests” on one of its angles, thus becoming a rhombus (phenomenic form). Now the dimensions given are those of the two diagonals of the represented rhombus (ABCD).

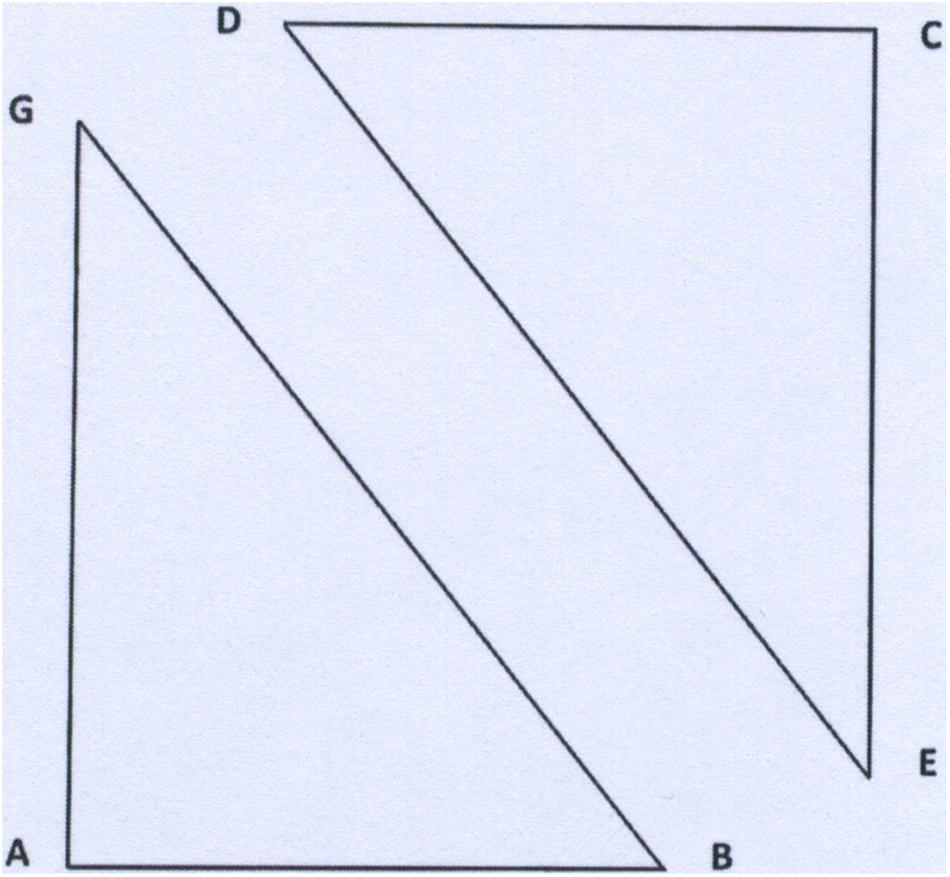

Figure 1. The study window problem solution.

The “inverted” version of the problem gave less trouble:

[…] The owner decides to make it smaller and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to halve the area of the window […].

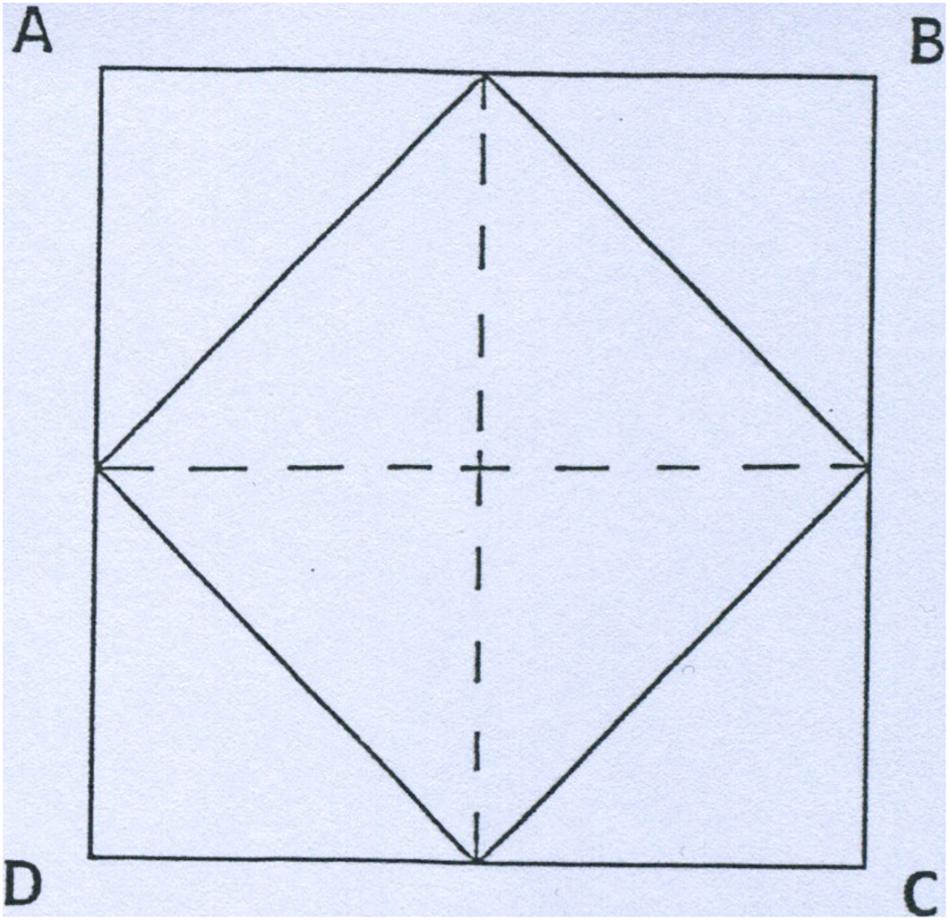

Figure 2. The inverted version.

With this version, 30% of the participants solved the problem ( n = 30). They started from the representation of the orthogonal square (ABCD) and looked for the solution within the square, trying to respect the required height and width of the window, and inevitably changing the orientation of the internal square. This time the height and width are the diagonals, rather than the side (base and height) of the square.

Eventually, in another version (the “orientation” version) it was explicit that orientation was not a mandatory attribute of the shape, and this time 66% of the participants found the solution immediately ( n = 30). This confirms the hypothesis that an inappropriate representation of the relation between the orthogonal orientation of the square and its geometric shape is the origin of the misunderstanding .

The “orientation” version:

A study window measures 1 m in height and 1 m wide. The owner decides to make it smaller and calls in a workman. He instructs the man to halve the area of the window: the workman can change the orientation of the window, but not its shape and in such a way that it still measures one meter by one meter. The workman carries out the commission. How did he do it?

While with the Study window problem the subjects who do not arrive at the solution, and who are the totality, know they are wrong, with the problem we are now going to examine, the Ties problem, those who are wrong do not realize it at all and the solution they propose is experienced as the correct solution.

The Ties Problem ( Mosconi and D’Urso, 1974 )

Peter and John have the same number of ties.

Peter gives John five of his ties.

How many ties does John have now more than Peter?

We believe that the seemingly trivial problem is actually the result of the simultaneous activation and mutual interference of complex cognitive processes that prevent its solution.

The problem has been submitted to 50 undergraduate students of the Humanities Faculty of the University of Milano-Bicocca. The participants were tested individually and were randomly assigned to three groups: control version ( n = 50), experimental version 2 ( n = 20), and experimental version 3 ( n = 23). All groups were tested in Italian. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the conditions and received a form containing only one version of the two assigned problems. There was no time limit. They were invited to think aloud and their spontaneous justifications were recorded and then transcribed.

The correct answer is obviously “ten,” but it must not be so obvious if it is given by only one third of the subjects (32%), while the remaining two thirds give the wrong answer “five,” which is so dominant.

If we consider the text of the problem from the point of view of the information explicitly transmitted ( said ), we have that it only theoretically provides the necessary information to reach the solution and precisely that: (a) the number of ties initially owned by P. and J. is equal, (b) P. gives J. five of his ties. However, the subjects are wrong. What emerges, however, from the spontaneous justifications given by the subjects who give the wrong answer is that they see only the increase of J. and not the consequent loss of P. by five ties. We report two typical justifications: “P. gives five of his to J., J. has five more ties than P., the five P. gave him” and also “They started from the same number of ties, so if P. gives J. five ties, J. should have five more than P.”

Slightly different from the previous ones is the following recurrent answer, in which the participants also consider the decrease of P. as well as the increase of J.: “I see five ties at stake, which are the ones that move,” or also “There are these five ties that go from one to the other, so one has five ties less and the other has five more,” reaching however the conclusion similar to the previous one that “J. has five ties more, because the other gave them to him.” 2

Almost always the participants who answer “five” use a numerical example to justify the answer given or to find a solution to the problem, after some unsuccessful attempts. It is paradoxical how many of these participants accept that the problem has two solutions, one “five ties” obtained by reasoning without considering a concrete number of initial ties, owned by P. and J., the other “ten ties” obtained by using a numerical example. So, for example, we read in the protocol of a participant who, after having answered “five more ties,” using a numerical example, finds “ten” of difference between the ties of P. and those of J.: “Well! I think the “five” is still more and more exact; for me this one has five more, period and that’s it.” “Making the concrete example: “ten” – he chases another subject on an abstract level. I would be more inclined to another formula, to five.”

About half of the subjects who give the answer “five,” in fact, at first refuse to answer because “we don’t know the initial number and therefore we can’t know how many ties J. has more than P.,” or at the most they answer: “J. has five ties more, P. five less, more we can’t know, because a data is missing.”

Even before this difficulty, so to speak, operational, the text of the problem is difficult because in it the quantity relative to the decrease of P. remains implicit (−5). The resulting misunderstanding is that if the quantity transferred is five ties, the resulting difference is only five ties: if the ties that P. gives to J. are five, how can J. have 10 ties more than P.?

So the difficulty of the problem lies in the discrepancy between the quantity transferred and the bidirectional effect that this quantity determines with its displacement. Resolving implies a restructuring of the sentence: “Peter gives John five of his ties (and therefore he loses five).” And this is precisely the reasoning carried out by those subjects who give the right answer “ten.”

We have therefore formulated a new version in which a pair of verbs should make explicit the loss of P.:

Peter loses five of his ties and John takes them.

However, the results obtained with this version, submitted to 20 other subjects, substantially confirm the results obtained with the original version: the correct answers are 17% (3/20) and the wrong ones 75% (15/20). From a Chi-square test (χ 2 = 2,088 p = 0.148) it results no significant difference between the two versions.

If we go to read the spontaneous justifications, we find that the subjects who give the answer “five” motivate it in a similar way to the subjects of the original version. So, for example: “P. loses five, J. gets them, so J. has five ties more than P.”

The decrease of P. is still not perceived, and the discrepancy between the lost amount of ties and the double effect that this quantity determines with its displacement persists.

Therefore, a new version has been realized in which the amount of ties lost by P. has nothing to do with J’s acquisition of five ties, the two amounts of ties are different and then they are perceived as decoupled, so as to neutralize the perceptual-conceptual factor underlying it.

Peter loses five of his ties and John buys five new ones.

It was submitted to 23 participants. Of them, 17 (74%) gave the answer “ten” and only 3 (13%) the answer “five.” There was a significant difference (χ 2 = 16,104 p = 0.000) between the results obtained using the present experimental version and the results from the control version. The participants who give the correct solution “ten” mostly motivate their answer as follows: “P. loses five and therefore J. has also those five that P. lost; he buys another five, there are ten,” declaring that he “added to the five that P. had lost the five that J. had bought.” The effectiveness of the experimental manipulation adopted is confirmed. 3

The satisfactory results obtained with this version cannot be attributed to the use of two different verbs, which proved to be ineffective (see version 2), but to the splitting, and consequent differentiation (J. has in addition five new ties), of the two quantities.

This time, the increase of J. and the decrease of P. are grasped as simultaneous and distinct and their combined effect is not identified with one or the other, but is equal to the sum of +5 and −5 in absolute terms.

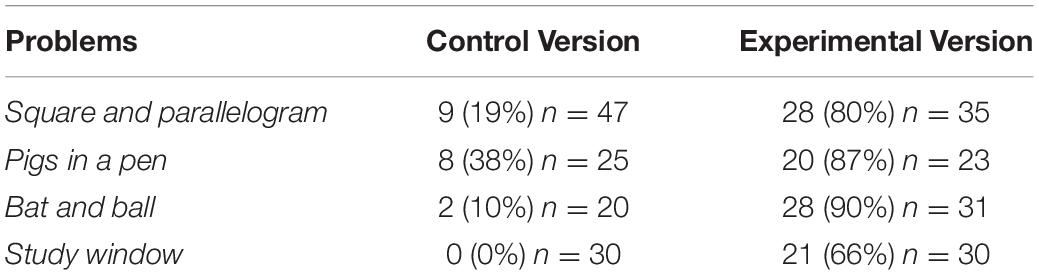

The hypothesis regarding the effect of reformulation has also been confirmed in classical insight problems such as the Square and the Parallelogram ( Wertheimer, 1925 ), the Pigs in a Pen ( Schooler et al., 1993 ), the Bat & Ball ( Frederick, 2005 ) in recent studies ( Macchi and Bagassi, 2012 , 2015 ) which showed a dramatic increase in the number of solutions.

In their original version these problems are true brain teasers, and the majority of participants in these studies needed them to be reformulated in order to reach the solution. In Appendix B we present in detail the results obtained (see Table 1 ). Below we report, for each problem, the text of the original version in comparison with the reformulated experimental version.

Table 1. Percentages of correct solutions with reformulated experimental versions.

Square and Parallelogram Problem ( Wertheimer, 1925 )

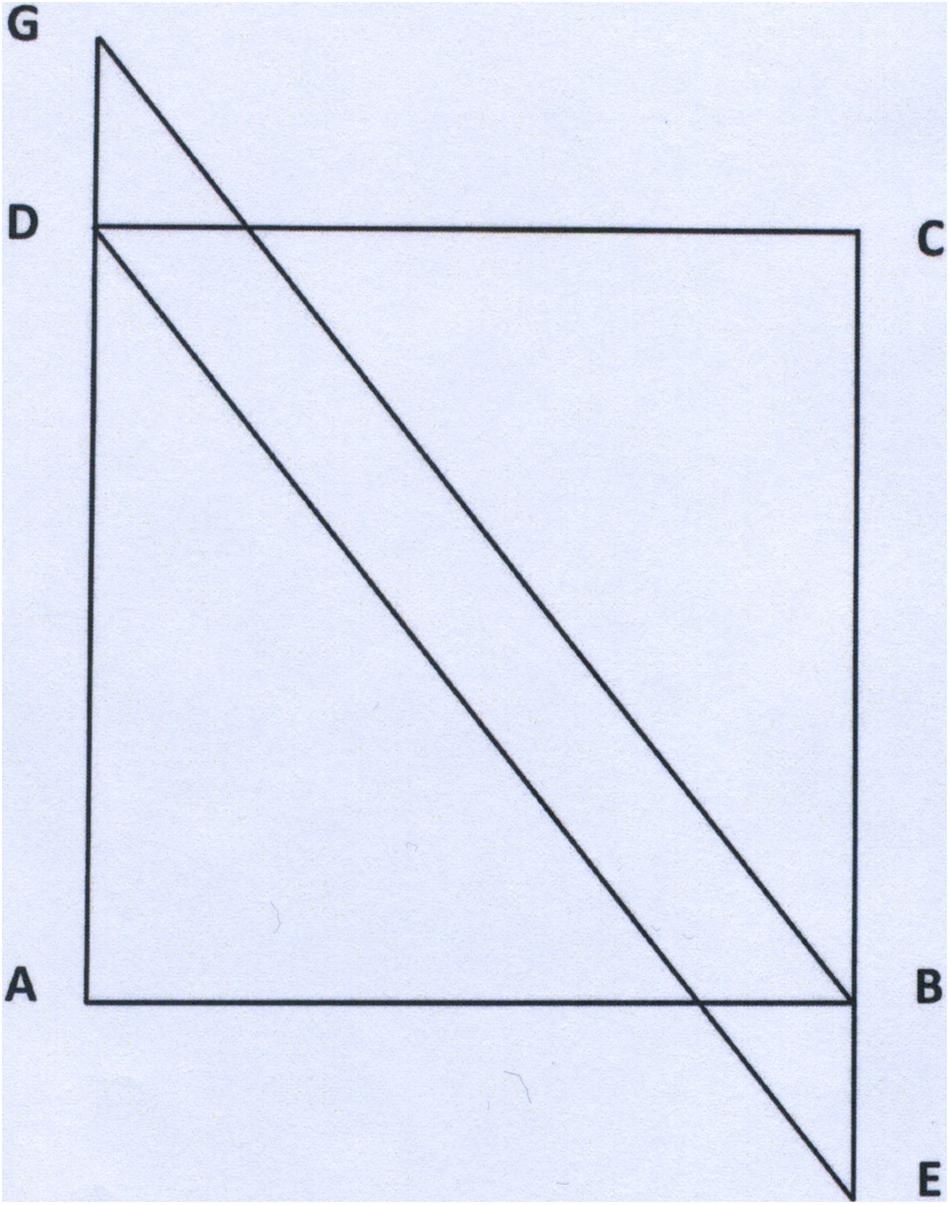

Given that AB = a and AG = b, find the sum of the areas of square ABCD and parallelogram EBGD ( Figures 3 , 4 ).

Figure 3. The square and parallelogram problem.

Figure 4. Solution.

Experimental Version

Given that AB = a and AG = b , find the sum of the areas of the two partially overlapping figures .

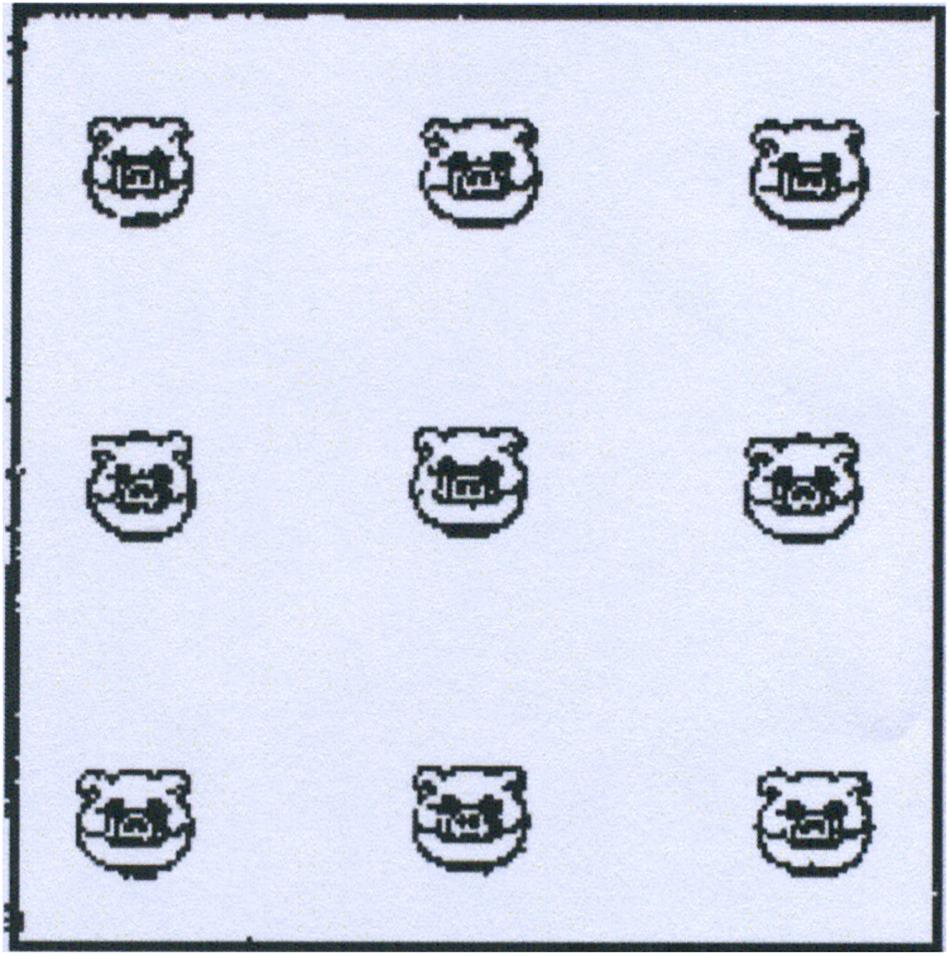

Pigs in a Pen Problem ( Schooler et al., 1993 )

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen . Build two more square enclosures that would put each pig in a pen by itself ( Figures 5 , 6 ).

Figure 5. The pigs in a pen problem.

Figure 6. Solution.

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen. Build two more squares that would put each pig in a by itself .

Bat and Ball Problem ( Frederick, 2005 )

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? ___cents.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. Find the cost of the bat and of the ball .

Once the problem knots that alter the aim of the task have been identified, the reformulation technique can be a valid didactic tool, as it allows to reveal the misunderstanding and to eliminate it without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. The training to creativity would consist in this sense in training to have interpretative keys different from the usual, when the difficulty cannot be addressed through computational techniques.

Closing Thoughts

By identifying the misunderstanding in problem solving, the reformulation technique has made it possible to eliminate the problem knots, without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. With the experimental reformulated versions of paradigmatic problems, both apparent trivial tasks or brain teasers have obtained a significant increase in correct answers.

Studying how an insight problem is formed, and not just how it is solved, may well become an important topic in education. We focus on undergraduate students’ strategies and their errors while solving problems, and the specific cognitive processes involved in misunderstanding, which are crucial to better exploit what could be beneficial to reach the solution and to teach how to improve the ability to solve problems.

Without violating the need for the necessary rigor of a demonstration, for example, it is possible to organize the problem-demonstration discourse according to a different criterion, precisely by favoring the psychological needs of the subject to whom the explanation discourse is addressed, taking care to organize the explanation with regard to the way his mind works, to what can favor its comprehension and facilitate its memory.

On the other hand, one of the criteria traditionally followed by mathematicians in constructing, for example, demonstrations, or at least in explaining them, is to never make any statement that is not supported by the elements provided above. In essence, in the course of the demonstration nothing is anticipated, and indeed it happens frequently that the propositions directly relevant and relevant to the development of the reasoning (for example, the steps of a geometric demonstration) are preceded by digressions intended to introduce and deal with the elements that legitimize them. As a consequence of such an expositive formalism, the recipient of the speech (the student) often finds himself in the situation of being led to the final conclusion a bit like a blind man who, even though he knows the goal, does not see the way, but can only control step by step the road he is walking along and with difficulty becomes aware of the itinerary.

The text of every problem, if formulated in natural language, has a psychorhetoric dimension, in the sense that in every speech, that is in the production and reception of every speech, there are aspects related to the way the mind works – and therefore psychological and rhetorical – that are decisive for comprehensibility, expressive adequacy and communicative effectiveness. It is precisely to these aspects that we refer to when we talk about the psychorhetoric dimension. Rhetoric, from the point of view of the broadcaster, has studied discourse in relation to the recipient, and therefore to its acceptability, comprehensibility and effectiveness, so that we can say that rhetoric has studied discourse “psychologically.”

Adopting this perspective, the commonplace that the rhetorical dimension only concerns the common discourse, i.e., the discourse that concerns debatable issues, and not the scientific discourse (logical-mathematical-demonstrative), which would be exempt from it, is falling away. The matter dealt with, the truth of what is actually said, is not sufficient to guarantee comprehension.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LM and MB devised the project, developed the theory, carried out the experiment and wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- ^ The theoretical framework assumed here is Paul Grice’s theory of communication (1975) based on the existence in communication of the explicit layer ( said ) and of the implicit ( implied ), so that the recognition of the communicative intention of the speaker by the interlocutor is crucial for comprehension.

- ^ A participant who after having given the solution “five” corrects himself in “ten” explains the first answer as follows: “it is more immediate, in my opinion, to see the real five ties that are moved, because they are five things that are moved; then as a more immediate answer is ‘five,’ because it is something more real, less mathematical.”

- ^ The factor indicated is certainly the main responsible for the answer “five,” but not the only one (see the Appendix for a pragmatic analysis of the text).

- ^ Versions and results of the problems exposed are already published in Macchi e Bagassi 2012, 2014, 2015.

Bagassi, M., and Macchi, L. (2006). Pragmatic approach to decision making under uncertainty: the case of the disjunction effect. Think. Reason. 12, 329–350. doi: 10.1080/13546780500375663

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bagassi, M., and Macchi, L. (2016). “The interpretative function and the emergence of unconscious analytic thought,” in Cognitive Unconscious and Human Rationality , eds L. Macchi, M. Bagassi, and R. Viale (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 43–76.

Google Scholar

Bulbrook, M. E. (1932). An experimental inquiry into the existence and nature of “insight”. Am. J. Psycho. 44, 409–453. doi: 10.2307/1415348

Duncker, K. (1945). “On problem solving,” in Psychological Monographs , Vol. 58, (Berlin: Springer), I–IX;1–113. Original in German, Psychologie des produktiven Denkens. doi: 10.1037/h0093599

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 19, 25–42. doi: 10.1257/089533005775196732

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am. Psychol. 58, 697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kaplan, C. A., and Simon, H. A. (1990). In search of insight. Cogn. Psychol. 22, 374–419. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(90)90008-R

Levinson, S. C. (1995). “Interactional biases in human thinking,” in Social Intelligence and Interaction , ed. E. N. Goody (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 221–261. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511621710.014

Levinson, S. C. (2013). “Cross-cultural universals and communication structures,” in Language, Music, and the Brain: A Mysterious Relationship , ed. M. A. Arbib (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 67–80. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262018104.003.0003

Macchi, L. (1995). Pragmatic aspects of the base-rate fallacy. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 4, 188–207. doi: 10.1080/14640749508401384

Macchi, L. (2000). Partitive formulation of information in probabilistic reasoning: beyond heuristics and frequency format explanations. Organ. Behav. Hum. 82, 217–236. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2000.2895

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2012). Intuitive and analytical processes in insight problem solving: a psycho-rhetorical approach to the study of reasoning. Mind Soc. 11, 53–67. doi: 10.1007/s11299-012-0103-3

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2014). The interpretative heuristic in insight problem solving. Mind Soc. 13, 97–108. doi: 10.1007/s11299-014-0139-7

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2015). When analytic thought is challenged by a misunderstanding. Think. Reas. 21, 147–164. doi: 10.4324/9781315144061-9

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2019). The argumentative and the interpretative functions of thought: two adaptive characteristics of the human cognitive system. Teorema 38, 87–96.

Macchi, L., and Bagassi, M. (2020). “Bounded rationality and problem solving: the interpretative function of thought,” in Handbook of Bounded Rationality , ed. Riccardo Viale (London: Routledge).

Mach, E. (1914). The Analysis of Sensations. Chicago IL: Open Court.

Mercier, H., and Sperber, D. (2011). Why do human reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 34, 57–74. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x10000968

Mosconi, G. (1990). Discorso e Pensiero. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Mosconi, G. (2016). “Closing thoughts,” in Cognive Unconscious and Human rationality , eds L. Macchi, M. Bagassi, and R. Viale (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 355–363. Original in Italian Discorso e pensiero.

Mosconi, G., and D’Urso, V. (1974). Il Farsi e il Disfarsi del Problema. Firenze: Giunti-Barbera.

Mosconi, G., and Macchi, L. (2001). The role of pragmatic rules in the conjunction fallacy. Mind Soc. 3, 31–57. doi: 10.1007/bf02512074

Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., and Simon, H. A. (1958). Elements of a theory of human problem solving. Psychol. Rev. 65, 151–166. doi: 10.1037/h0048495

Politzer, G., and Macchi, L. (2000). Reasoning and pragmatics. Mind Soc. 1, 73–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02512230

Schooler, J. W., Ohlsson, S., and Brooks, K. (1993). Thoughts beyond words: when language overshadows insight. J. Exp. Psychol. 122, 166–183. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.122.2.166

Simon, H. A. (1979). Information processing models of cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 30, 363–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.30.020179.002051

Sperber, D., and Wilson, D. (1986/1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why We Cooperate. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/8470.001.0001

Wertheimer, M. (1925). Drei Abhandlungen zur Gestalttheorie. Erlangen: Verlag der Philosophischen Akademie.

Wertheimer, M. (1959). Productive Thinking. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Wertheimer, M. (1985). A gestalt perspective on computer simulations of cognitive processes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1, 19–33. doi: 10.1016/0747-5632(85)90004-4

Pragmatic analysis of the problematic loci of the Ties problem, which emerged from the spontaneous verbalizations of the participants:

- “the same number of ties”

This expression is understood as a neutral information, a kind of base or sliding plane on which the transfer of the five ties takes place and, in fact, these subjects motivate their answer “five” with: “there is this transfer of five ties from P. to J. ….”

- “5 more, 5 less”

We frequently resort to similar expressions in situations where, if I have five units more than another, the other has five less than me and the difference between us is five.

Consider, for example, the case of the years: say that J. is five years older than P. means to say that P. is five years younger than J. and that the difference in years between the two is five, not ten.

In comparisons, we evaluate the difference with something used as a term of reference, for example the age of P., which serves as a basis, the benchmark, precisely.

- “he gives”

The verb “to give” conveys the concept of the growth of the recipient, not the decrease of the giver, therefore, contributes to the crystallization of the “same number,” preventing to grasp the decrease of P.

Appendix B 4

Given that AB = a and AG = b, find the sum of the areas of square ABCD and parallelogram EBGD .

Typically, problem solvers find the problem difficult and fail to see that a is also the altitude of parallelogram EBGD. They tend to calculate its area with onerous and futile methods, while the solution can be reached with a smart method, consisting of restructuring the entire given shape into two partially overlapping triangles ABG and ECD. The sum of their areas is 2 x a b /2 = a b . Moreover, by shifting one of the triangles so that DE coincides with GB, the answer is “ a b ,” which is the area of the resultant rectangle. Referring to a square and a parallelogram fixes a favored interpretation of the perceptive stimuli, according to those principles of perceptive organization thoroughly studied by the Gestalt Theory. It firmly sets the calculation of the area on the sum of the two specific shapes dealt with in the text, while, the problem actually requires calculation of the area of the shape, however organized, as the sum of two triangles rectangles, or the area of only one rectangle, as well as the sum of square and parallelogram. Hence, the process of restructuring is quite difficult.

To test our hypotheses we formulated an experimental version:

In this formulation of the problem, the text does not impose constraints on the interpretation/organization of the figure, and the spontaneous, default interpretation is no longer fixed. Instead of asking for “the areas of square and parallelogram,” the problem asks for the areas of “the two partially overlapping figures.” We predicted that the experimental version would allow the subjects to see and consider the two triangles also.

Actually, we found that 80% of the participants (28 out of 35) gave a correct answer, and most of them (21 out of 28) gave the smart “two triangles” solution. In the control version, on the other hand, only 19% (9 out of 47) gave the correct response, and of these only two gave the “two triangles” solution.

The findings were replicated in the “Pigs in a pen” problem:

Nine pigs are kept in a square pen . Build two more square enclosures that would put each pig in a pen by itself.

The difficulty of this problem lies in the interpretation of the request, nine pigs each individually enclosed in a square pen, having only two more square enclosures. This interpretation is supported by the favored, orthogonal reference scheme, with which we represent the square. This privileged organization, according to our hypothesis, is fixed by the text which transmits the implicature that the pens in which the piglets are individually isolated must be square in shape too. The function of enclosure wrongfully implies the concept of a square. The task, on the contrary, only requires to pen each pig.

Once again, we created an experimental version by reformulating the problem, eliminating the word “enclosure” and the phrase “in a pen.” The implicit inference that the pen is necessarily square is not drawn.

The experimental version yielded 87% correct answers (20 out of 23), while the control version yielded only 38% correct answers (8 out of 25).

The formulation of the experimental versions was more relevant to the aim of the task, and allowed the perceptual stimuli to be interpreted in accordance with the solution.

The relevance of text and the re-interpretation of perceptual stimuli, goal oriented to the aim of the task, were worked out in unison in an interrelated interpretative “game.”

We further investigated the interpretative activity of thinking, by studying the “Bat and ball” problem, which is part of the CRT. Correct performance is usually considered to be evidence of reflective cognitive ability (correlated with high IQ scores), versus intuitive, erroneous answers to the problem ( Frederick, 2005 ).

Bat and Ball problem

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $ 1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?___cents

Of course the answer which immediately comes to mind is 10 cents, which is incorrect as, in this case, the difference between $ 1.00 and 10 cents is only 90 cents, not $1.00 as the problem stipulates. The correct response is 5 cents.

Number physiognomics and the plausibility of the cost are traditionally considered responsible for this kind of error ( Frederick, 2005 ; Kahneman, 2003 ).

These factors aside, we argue that if the rhetoric structure of the text is analyzed, the question as formulated concerns only the ball, implying that the cost of the bat is already known. The question gives the key to the interpretation of what has been said in each problem and, generally speaking, in every discourse. Given data, therefore, is interpreted in the light of the question. Hence, “The bat costs $ 1.00 more than” becomes “The bat costs $ 1.00,” by leaving out “more than.”

According to our hypothesis, independently of the different cognitive styles, erroneous responses could be the effect of the rhetorical structure of the text, where the question is not adequate to the aim of the task. Consequently, we predicted that if the question were to be reformulated to become more relevant, the subjects would find it easier to grasp the correct response. In the light of our perspective, the cognitive abilities involved in the correct response were also reinterpreted. Consequently, we reformulated the text as follows in order to eliminate this misleading inference:

This time we predicted an increase in the number of correct answers. The difference in the percentages of correct solutions was significant: in the experimental version 90% of the participants gave a correct answer (28 out of 31), and only 10% (2 out of 20) answered correctly in the control condition.

The simple reformulation of the question, which expresses the real aim of the task (to find the cost of both items), does not favor the “short circuit” of considering the cost of the bat as already known (“$1,” by leaving out part of the phrase “more than”).

It still remains to be verified if those subjects who gave the correct response in the control version have a higher level of cognitive reflexive ability compared to the “intuitive” respondents. This has been the general interpretation given in the literature to the difference in performance.

We think it is a matter of a particular kind of reflexive ability, due to which the task is interpreted in the light of the context and not abstracting from it. The difficulty which the problem implicates does not so much involve a high level of abstract reasoning ability as high levels of pragmatic competence, which disambiguates the text. So much so that, intervening only on the pragmatic level, keeping numbers physiognomics and maintaining the plausible costs identical, the problem becomes a trivial arithmetical task.

Keywords : creative problem solving, insight, misunderstanding, pragmatics, language and thought

Citation: Bagassi M and Macchi L (2020) Creative Problem Solving as Overcoming a Misunderstanding. Front. Educ. 5:538202. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.538202

Received: 26 February 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 03 December 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Bagassi and Macchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Macchi, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Psychology and Mathematics Education

Creative Problem Solving as Overcoming a Misunderstanding

M. Bagassi , L. Macchi

Dec 1, 2020

Influential Citations

Journal name not available for this finding

Key Takeaway : Insight problem solving involves identifying and resolving misunderstandings, improving students' ability to solve complex problems.

Solving or attempting to solve problems is the typical and, hence, general function of thought. A theory of problem solving must first explain how the problem is constituted, and then how the solution happens, but also how it happens that it is not solved; it must explain the correct answer and with the same means the failure. The identification of the way in which the problem is formatted should help to understand how the solution of the problems happens, but even before that, the source of the difficulty. Sometimes the difficulty lies in the calculation, the number of operations to be performed, and the quantity of data to be processed and remembered. There are, however, other problems – the insight problems – in which the difficulty does not lie so much in the complexity of the calculations, but in one or more critical points that are susceptible to misinterpretation, incompatible with the solution. In our view, the way of thinking involved in insight problem solving is very close to the process involved in the understanding of an utterance, when a misunderstanding occurs. In this case, a more appropriate meaning has to be selected to resolve the misunderstanding (the “impasse”), the default interpretation (the “fixation”) has to be dropped in order to “restructure.” to grasp another meaning which appears more relevant to the context and the speaker’s intention (the “aim of the task”). In this article we support our view with experimental evidence, focusing on how a misunderstanding is formed. We have studied a paradigmatic insight problem, an apparent trivial arithmetical task, the Ties problem. We also reviewed other classical insight problems, reconsidering in particular one of the most intriguing one, which at first sight appears impossible to solve, the Study Window problem. By identifying the problem knots that alter the aim of the task, the reformulation technique has made it possible to eliminate misunderstanding, without changing the mathematical nature of the problem. With the experimental versions of the problems exposed we have obtained a significant increase in correct answers. Studying how an insight problem is formed, and not just how it is solved, may well become an important topic in education. We focus on undergraduate students’ strategies and their errors while solving problems, and the specific cognitive processes involved in misunderstanding, which are crucial to better exploit what could be beneficial to reach the solution and to teach how to improve the ability to solve problems.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Creative Problem Solving

Finding innovative solutions to challenges.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine that you're vacuuming your house in a hurry because you've got friends coming over. Frustratingly, you're working hard but you're not getting very far. You kneel down, open up the vacuum cleaner, and pull out the bag. In a cloud of dust, you realize that it's full... again. Coughing, you empty it and wonder why vacuum cleaners with bags still exist!

James Dyson, inventor and founder of Dyson® vacuum cleaners, had exactly the same problem, and he used creative problem solving to find the answer. While many companies focused on developing a better vacuum cleaner filter, he realized that he had to think differently and find a more creative solution. So, he devised a revolutionary way to separate the dirt from the air, and invented the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner. [1]

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of solving problems or identifying opportunities when conventional thinking has failed. It encourages you to find fresh perspectives and come up with innovative solutions, so that you can formulate a plan to overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

In this article, we'll explore what CPS is, and we'll look at its key principles. We'll also provide a model that you can use to generate creative solutions.

About Creative Problem Solving

Alex Osborn, founder of the Creative Education Foundation, first developed creative problem solving in the 1940s, along with the term "brainstorming." And, together with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. Despite its age, this model remains a valuable approach to problem solving. [2]

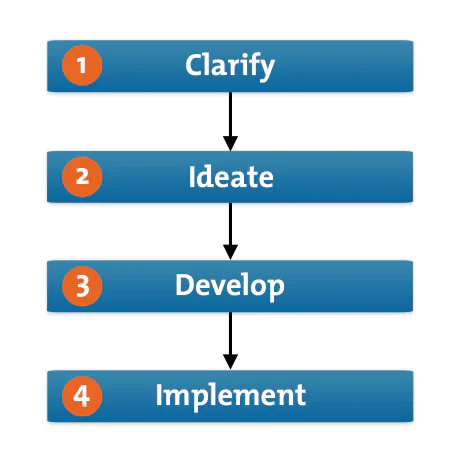

The early Osborn-Parnes model inspired a number of other tools. One of these is the 2011 CPS Learner's Model, also from the Creative Education Foundation, developed by Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Marie Mance, and co-workers. In this article, we'll use this modern four-step model to explore how you can use CPS to generate innovative, effective solutions.

Why Use Creative Problem Solving?

Dealing with obstacles and challenges is a regular part of working life, and overcoming them isn't always easy. To improve your products, services, communications, and interpersonal skills, and for you and your organization to excel, you need to encourage creative thinking and find innovative solutions that work.

CPS asks you to separate your "divergent" and "convergent" thinking as a way to do this. Divergent thinking is the process of generating lots of potential solutions and possibilities, otherwise known as brainstorming. And convergent thinking involves evaluating those options and choosing the most promising one. Often, we use a combination of the two to develop new ideas or solutions. However, using them simultaneously can result in unbalanced or biased decisions, and can stifle idea generation.

For more on divergent and convergent thinking, and for a useful diagram, see the book "Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making." [3]

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

CPS has four core principles. Let's explore each one in more detail:

- Divergent and convergent thinking must be balanced. The key to creativity is learning how to identify and balance divergent and convergent thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice each one.

- Ask problems as questions. When you rephrase problems and challenges as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities, it's easier to come up with solutions. Asking these types of questions generates lots of rich information, while asking closed questions tends to elicit short answers, such as confirmations or disagreements. Problem statements tend to generate limited responses, or none at all.

- Defer or suspend judgment. As Alex Osborn learned from his work on brainstorming, judging solutions early on tends to shut down idea generation. Instead, there's an appropriate and necessary time to judge ideas during the convergence stage.

- Focus on "Yes, and," rather than "No, but." Language matters when you're generating information and ideas. "Yes, and" encourages people to expand their thoughts, which is necessary during certain stages of CPS. Using the word "but" – preceded by "yes" or "no" – ends conversation, and often negates what's come before it.

How to Use the Tool

Let's explore how you can use each of the four steps of the CPS Learner's Model (shown in figure 1, below) to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

Figure 1 – CPS Learner's Model

Explore the Vision

Identify your goal, desire or challenge. This is a crucial first step because it's easy to assume, incorrectly, that you know what the problem is. However, you may have missed something or have failed to understand the issue fully, and defining your objective can provide clarity. Read our article, 5 Whys , for more on getting to the root of a problem quickly.

Gather Data

Once you've identified and understood the problem, you can collect information about it and develop a clear understanding of it. Make a note of details such as who and what is involved, all the relevant facts, and everyone's feelings and opinions.

Formulate Questions

When you've increased your awareness of the challenge or problem you've identified, ask questions that will generate solutions. Think about the obstacles you might face and the opportunities they could present.

Explore Ideas

Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions you identified in step 1. It can be tempting to consider solutions that you've tried before, as our minds tend to return to habitual thinking patterns that stop us from producing new ideas. However, this is a chance to use your creativity .

Brainstorming and Mind Maps are great ways to explore ideas during this divergent stage of CPS. And our articles, Encouraging Team Creativity , Problem Solving , Rolestorming , Hurson's Productive Thinking Model , and The Four-Step Innovation Process , can also help boost your creativity.

See our Brainstorming resources within our Creativity section for more on this.

Formulate Solutions

This is the convergent stage of CPS, where you begin to focus on evaluating all of your possible options and come up with solutions. Analyze whether potential solutions meet your needs and criteria, and decide whether you can implement them successfully. Next, consider how you can strengthen them and determine which ones are the best "fit." Our articles, Critical Thinking and ORAPAPA , are useful here.

4. Implement

Formulate a plan.

Once you've chosen the best solution, it's time to develop a plan of action. Start by identifying resources and actions that will allow you to implement your chosen solution. Next, communicate your plan and make sure that everyone involved understands and accepts it.

There have been many adaptations of CPS since its inception, because nobody owns the idea.

For example, Scott Isaksen and Donald Treffinger formed The Creative Problem Solving Group Inc . and the Center for Creative Learning , and their model has evolved over many versions. Blair Miller, Jonathan Vehar and Roger L. Firestien also created their own version, and Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Mary C. Murdock, and Marie Mance developed CPS: The Thinking Skills Model. [4] Tim Hurson created The Productive Thinking Model , and Paul Reali developed CPS: Competencies Model. [5]

Sid Parnes continued to adapt the CPS model by adding concepts such as imagery and visualization , and he founded the Creative Studies Project to teach CPS. For more information on the evolution and development of the CPS process, see Creative Problem Solving Version 6.1 by Donald J. Treffinger, Scott G. Isaksen, and K. Brian Dorval. [6]

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Infographic

See our infographic on Creative Problem Solving .

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

There have been many adaptations of the original Osborn-Parnes model, but they all involve a clear structure of identifying the problem, generating new ideas, evaluating the options, and then formulating a plan for successful implementation.

[1] Entrepreneur (2012). James Dyson on Using Failure to Drive Success [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 27, 2022.]

[2] Creative Education Foundation (2015). The CPS Process [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022.]

[3] Kaner, S. et al. (2014). 'Facilitator′s Guide to Participatory Decision–Making,' San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Puccio, G., Mance, M., and Murdock, M. (2011). 'Creative Leadership: Skils That Drive Change' (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[5] OmniSkills (2013). Creative Problem Solving [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022].

[6] Treffinger, G., Isaksen, S., and Dorval, B. (2010). Creative Problem Solving (CPS Version 6.1). Center for Creative Learning, Inc. & Creative Problem Solving Group, Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Simplex thinking.

8 Steps for Solving Complex Problems

Book Insights

Solving Tough Problems: An Open Way of Talking, Listening, and Creating New Realities

Adam Kahane (Foreword by Peter Senge)

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Nine Ways to Get the Best From X (Twitter)

The Sales Funnel

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Take the stress out of your life.

Expert Interviews

Eight Classic Mistakes Interviewers Make Infographic

Infographic Transcript

Infographic

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Project management for non-project managers.

Understanding the principles of project management

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How to Be a More Creative Problem-Solver at Work: 8 Tips

- 01 Mar 2022

The importance of creativity in the workplace—particularly when problem-solving—is undeniable. Business leaders can’t approach new problems with old solutions and expect the same result.

This is where innovation-based processes need to guide problem-solving. Here’s an overview of what creative problem-solving is, along with tips on how to use it in conjunction with design thinking.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Encountering problems with no clear cause can be frustrating. This occurs when there’s disagreement around a defined problem or research yields unclear results. In such situations, creative problem-solving helps develop solutions, despite a lack of clarity.

While creative problem-solving is less structured than other forms of innovation, it encourages exploring open-ended ideas and shifting perspectives—thereby fostering innovation and easier adaptation in the workplace. It also works best when paired with other innovation-based processes, such as design thinking .

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Design thinking is a solutions-based mentality that encourages innovation and problem-solving. It’s guided by an iterative process that Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar outlines in four stages in the online course Design Thinking and Innovation :

- Clarify: This stage involves researching a problem through empathic observation and insights.

- Ideate: This stage focuses on generating ideas and asking open-ended questions based on observations made during the clarification stage.

- Develop: The development stage involves exploring possible solutions based on the ideas you generate. Experimentation and prototyping are both encouraged.

- Implement: The final stage is a culmination of the previous three. It involves finalizing a solution’s development and communicating its value to stakeholders.

Although user research is an essential first step in the design thinking process, there are times when it can’t identify a problem’s root cause. Creative problem-solving addresses this challenge by promoting the development of new perspectives.

Leveraging tools like design thinking and creativity at work can further your problem-solving abilities. Here are eight tips for doing so.

8 Creative Problem-Solving Tips

1. empathize with your audience.

A fundamental practice of design thinking’s clarify stage is empathy. Understanding your target audience can help you find creative and relevant solutions for their pain points through observing them and asking questions.

Practice empathy by paying attention to others’ needs and avoiding personal comparisons. The more you understand your audience, the more effective your solutions will be.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

If a problem is difficult to define, reframe it as a question rather than a statement. For example, instead of saying, "The problem is," try framing around a question like, "How might we?" Think creatively by shifting your focus from the problem to potential solutions.

Consider this hypothetical case study: You’re the owner of a local coffee shop trying to fill your tip jar. Approaching the situation with a problem-focused mindset frames this as: "We need to find a way to get customers to tip more." If you reframe this as a question, however, you can explore: "How might we make it easier for customers to tip?" When you shift your focus from the shop to the customer, you empathize with your audience. You can take this train of thought one step further and consider questions such as: "How might we provide a tipping method for customers who don't carry cash?"

Whether you work at a coffee shop, a startup, or a Fortune 500 company, reframing can help surface creative solutions to problems that are difficult to define.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

If you encounter an idea that seems outlandish or unreasonable, a natural response would be to reject it. This instant judgment impedes creativity. Even if ideas seem implausible, they can play a huge part in ideation. It's important to permit the exploration of original ideas.

While judgment can be perceived as negative, it’s crucial to avoid accepting ideas too quickly. If you love an idea, don’t immediately pursue it. Give equal consideration to each proposal and build on different concepts instead of acting on them immediately.

4. Overcome Cognitive Fixedness

Cognitive fixedness is a state of mind that prevents you from recognizing a situation’s alternative solutions or interpretations instead of considering every situation through the lens of past experiences.

Although it's efficient in the short-term, cognitive fixedness interferes with creative thinking because it prevents you from approaching situations unbiased. It's important to be aware of this tendency so you can avoid it.

5. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

One of the key principles of creative problem-solving is the balance of divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is the process of brainstorming multiple ideas without limitation; open-ended creativity is encouraged. It’s an effective tool for generating ideas, but not every idea can be explored. Divergent thinking eventually needs to be grounded in reality.

Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is the process of narrowing ideas down into a few options. While converging ideas too quickly stifles creativity, it’s an important step that bridges the gap between ideation and development. It's important to strike a healthy balance between both to allow for the ideation and exploration of creative ideas.

6. Use Creative Tools

Using creative tools is another way to foster innovation. Without a clear cause for a problem, such tools can help you avoid cognitive fixedness and abrupt decision-making. Here are several examples:

Problem Stories

Creating a problem story requires identifying undesired phenomena (UDP) and taking note of events that precede and result from them. The goal is to reframe the situations to visualize their cause and effect.

To start, identify a UDP. Then, discover what events led to it. Observe and ask questions of your consumer base to determine the UDP’s cause.

Next, identify why the UDP is a problem. What effect does the UDP have that necessitates changing the status quo? It's helpful to visualize each event in boxes adjacent to one another when answering such questions.

The problem story can be extended in either direction, as long as there are additional cause-and-effect relationships. Once complete, focus on breaking the chains connecting two subsequent events by disrupting the cause-and-effect relationship between them.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool encourages you to consider how people from different backgrounds would approach similar situations. For instance, how would someone in hospitality versus manufacturing approach the same problem? This tool isn't intended to instantly solve problems but, rather, to encourage idea generation and creativity.

7. Use Positive Language

It's vital to maintain a positive mindset when problem-solving and avoid negative words that interfere with creativity. Positive language prevents quick judgments and overcomes cognitive fixedness. Instead of "no, but," use words like "yes, and."

Positive language makes others feel heard and valued rather than shut down. This practice doesn’t necessitate agreeing with every idea but instead approaching each from a positive perspective.

Using “yes, and” as a tool for further idea exploration is also effective. If someone presents an idea, build upon it using “yes, and.” What additional features could improve it? How could it benefit consumers beyond its intended purpose?

While it may not seem essential, this small adjustment can make a big difference in encouraging creativity.

8. Practice Design Thinking

Practicing design thinking can make you a more creative problem-solver. While commonly associated with the workplace, adopting a design thinking mentality can also improve your everyday life. Here are several ways you can practice design thinking:

- Learn from others: There are many examples of design thinking in business . Review case studies to learn from others’ successes, research problems companies haven't addressed, and consider alternative solutions using the design thinking process.

- Approach everyday problems with a design thinking mentality: One of the best ways to practice design thinking is to apply it to your daily life. Approach everyday problems using design thinking’s four-stage framework to uncover what solutions it yields.

- Study design thinking: While learning design thinking independently is a great place to start, taking an online course can offer more insight and practical experience. The right course can teach you important skills , increase your marketability, and provide valuable networking opportunities.

Ready to Become a Creative Problem-Solver?

Though creativity comes naturally to some, it's an acquired skill for many. Regardless of which category you're in, improving your ability to innovate is a valuable endeavor. Whether you want to bolster your creativity or expand your professional skill set, taking an innovation-based course can enhance your problem-solving.

If you're ready to become a more creative problem-solver, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses . If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

What is creative problem-solving?

Table of Contents

An introduction to creative problem-solving.

Creative problem-solving is an essential skill that goes beyond basic brainstorming . It entails a holistic approach to challenges, melding logical processes with imaginative techniques to conceive innovative solutions. As our world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, the ability to think creatively and solve problems with fresh perspectives becomes invaluable for individuals, businesses, and communities alike.

Importance of divergent and convergent thinking

At the heart of creative problem-solving lies the balance between divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking encourages free-flowing, unrestricted ideation, leading to a plethora of potential solutions. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is about narrowing down those options to find the most viable solution. This dual approach ensures both breadth and depth in the problem-solving process.

Emphasis on collaboration and diverse perspectives

No single perspective has a monopoly on insight. Collaborating with individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and areas of expertise offers a richer tapestry of ideas. Embracing diverse perspectives not only broadens the pool of solutions but also ensures more holistic and well-rounded outcomes.

Nurturing a risk-taking and experimental mindset

The fear of failure can be the most significant barrier to any undertaking. It's essential to foster an environment where risk-taking and experimentation are celebrated. This involves viewing failures not as setbacks but as invaluable learning experiences that pave the way for eventual success.

The role of intuition and lateral thinking

Sometimes, the path to a solution is not linear. Lateral thinking and intuition allow for making connections between seemingly unrelated elements. These 'eureka' moments often lead to breakthrough solutions that conventional methods might overlook.

Stages of the creative problem-solving process

The creative problem-solving process is typically broken down into several stages. Each stage plays a crucial role in understanding, addressing, and resolving challenges in innovative ways.

Clarifying: Understanding the real problem or challenge

Before diving into solutions, one must first understand the problem at its core. This involves asking probing questions, gathering data, and viewing the challenge from various angles. A clear comprehension of the problem ensures that effort and resources are channeled correctly.

Ideating: Generating diverse and multiple solutions

Once the problem is clarified, the focus shifts to generating as many solutions as possible. This stage champions quantity over quality, as the aim is to explore the breadth of possibilities without immediately passing judgment.

Developing: Refining and honing promising solutions

With a list of potential solutions in hand, it's time to refine and develop the most promising ones. This involves evaluating each idea's feasibility, potential impact, and any associated risks, then enhancing or combining solutions to maximize effectiveness.

Implementing: Acting on the best solutions

Once a solution has been honed, it's time to put it into action. This involves planning, allocating resources, and monitoring the results to ensure the solution is effectively addressing the problem.

Techniques for creative problem-solving

Solving complex problems in a fresh way can be a daunting task to start on. Here are a few techniques that can help kickstart the process:

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a widely-used technique that involves generating as many ideas as possible within a set timeframe. Variants like brainwriting (where ideas are written down rather than spoken) and reverse brainstorming (thinking of ways to cause the problem) can offer fresh perspectives and ensure broader participation.

Mind mapping

Mind mapping is a visual tool that helps structure information, making connections between disparate pieces of data. It is particularly useful in organizing thoughts, visualizing relationships, and ensuring a comprehensive approach to a problem.

SCAMPER technique

SCAMPER stands for Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse. This technique prompts individuals to look at existing products, services, or processes in new ways, leading to innovative solutions.

Benefits of creative problem-solving

Creative problem-solving offers numerous benefits, both at the individual and organizational levels. Some of the most prominent advantages include:

Finding novel solutions to old problems

Traditional problems that have resisted conventional solutions often succumb to creative approaches. By looking at challenges from fresh angles and blending different techniques, we can unlock novel solutions previously deemed impossible.

Enhanced adaptability in changing environments

In our rapidly evolving world, the ability to adapt is critical. Creative problem-solving equips individuals and organizations with the agility to pivot and adapt to changing circumstances, ensuring resilience and longevity.

Building collaborative and innovative teams

Teams that embrace creative problem-solving tend to be more collaborative and innovative. They value diversity of thought, are open to experimentation, and are more likely to challenge the status quo, leading to groundbreaking results.

Fostering a culture of continuous learning and improvement

Creative problem-solving is not just about finding solutions; it's also about continuous learning and improvement. By encouraging an environment of curiosity and exploration, organizations can ensure that they are always at the cutting edge, ready to tackle future challenges head-on.

Get on board in seconds

Join thousands of teams using Miro to do their best work yet.

Problem-Solving Mindset: How to Achieve It (15 Ways)

One of the most valuable skills you can have in life is a problem-solving mindset. It means that you see challenges as opportunities to learn and grow, rather than obstacles to avoid or complain about. A problem-solving mindset helps you overcome difficulties, achieve your goals, and constantly improve yourself. By developing a problem-solving mindset, you can become more confident, creative, and resilient in any situation.A well-defined problem paves the way for targeted, effective solutions. Resist the urge to jump straight into fixing things. Invest the time upfront to truly understand what needs to be solved. Starting with the end in mind will make the path to resolution that much smoother.

Sanju Pradeepa

* This Post may contain affiliate Links, and we receive an affiliate commission for any purchases made by you using such links. *

Ever feel like you’re stuck in a rut with no way out? We’ve all been there. The problems life throws at us can seem insurmountable. But the truth is, you have everything you need to overcome any challenge already within you. It’s called a problem-solving mindset. Developing the ability to see problems as puzzles to solve rather than obstacles to overcome is a game changer. With the right mindset, you can achieve amazing things.

In this article, we’ll explore what having a problem-solving mindset really means and how you can cultivate one for yourself. You’ll learn proven techniques to shift your perspective, expand your creativity, and find innovative solutions to your biggest problems. We’ll look at examples of people who have used a problem-solving mindset to accomplish extraordinary feats. By the end, you’ll have the tools and inspiration to transform how you think about and approach problems in your own life.

Table of Contents

What is a problem-solving mindset.

A problem solving mindset is all about approaching challenges in a solution-focused way. Rather than feeling defeated by obstacles, you look at them as puzzles to solve. Developing this mindset takes practice, but the rewards of increased resilience, creativity and confidence make it worth the effort.