Everyone Wants an "A": The Role of Academic Expectations in Academic Performance

Degree type.

- Master of Science

- Psychological Sciences

Campus location

- Indianapolis

Advisor/Supervisor/Committee Chair

Additional committee member 2, additional committee member 3, usage metrics.

- Clinical psychology

Advertisement

Academic expectations among university students and staff: addressing the role of psychological contracts and social norms

- Published: 30 January 2021

- Volume 82 , pages 847–863, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Ryan Naylor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6880-6463 1 ,

- Fiona L. Bird 2 &

- Nicole E. Butler 2

2415 Accesses

9 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Student expectations of required workload, behaviour, resource use, role and relationship profoundly shape success in higher education and inform satisfaction with their learning experience. Teachers’ expectations of students’ behaviour can similarly affect the university learning experience and environment. When expectations between academic staff and students are not aligned, student satisfaction and staff morale are likely to suffer. This study sought to identify areas where the academic expectations of students and staff aligned or diverged and understand responses to any breaches of expectations. Here, we report on qualitative findings from a survey of 259 undergraduate students and 48 staff members and focus group interviews with 10 students and 15 staff members. Although their academic expectations aligned in most areas, students appeared to have broader conceptions of success at university than staff, and a stronger focus on the importance of personal relationships with staff and teaching quality. Academics expressed stronger injunctive norms about prioritisation of study and the importance of identifying as a student. These differences are likely to lead to tension between the two groups, particularly in areas of value for individuals. While clarifying expectations may improve alignment between the groups to some extent, the basis of these differences in individual priorities suggests that merely articulating expectations may not resolve the issue. We therefore argue for staff to adopt a co-creation approach to academic expectations and to ‘meet students halfway’ where possible.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Resources, Training, and Support for Early Career Academics: Mixed Messages and Unfulfilled Expectations

Student engagement in academic activities: a social support perspective.

Matthew J. Xerri, Katrina Radford & Kate Shacklock

What is required to develop career pathways for teaching academics?

Dawn Bennett, Lynne Roberts, … Michelle Broughton

Appleton-Knapp, S. L., & Krentler, K. A. (2006). Measuring student expectations and their effects on satisfaction: the importance of managing student expectations. Journal of marketing education, 28 (3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475306293359 .

Article Google Scholar

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., Brooker, A., Wyn, J., Allen, L., Brett, M., et al. (2017). Enhancing mental wellbeing: a handbook for academic educators . Melbourne: Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Google Scholar

Baik, C., Naylor, R., & Arkoudis, S. (2015). The first year experience in Australian universities: finding from two decades, 1994–2014 . Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

Breckler, S. J. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of personality and social psychology, 47 (6), 1191.

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., & van Haeringen, K. (2019). Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Studies in higher education, 44 (11), 1837–1856. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788 .

Brinkworth, R., McCann, B., Matthews, C., & Nordström, K. (2009). First year expectations and experiences: student and teacher perspectives. Higher Education, 58 (2), 157–173.

Cheng, M., Taylor, J., Williams, J., & Tong, K. (2016). Student satisfaction and perceptions of quality: testing the linkages for PhD students. Higher Education Research & Development, 35 (6), 1153–1166.

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 201–234). San Diego: Academic Press Inc.

Collier, P. J., & Morgan, D. L. (2008). “Is that paper really due today?”: differences in first-generation and traditional college students’ understandings of faculty expectations. Higher Education, 55 (4), 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9065-5 .

Dabos, G. E., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Mutuality and reciprocity in the psychological contracts of employees and employers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89 (1), 52.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual review of psychology, 53 (1), 109–132.

Haslam, S. A., Oakes, P. J., Turner, J. C., & McGarty, C. (1995). Social categorization and group homogeneity: changes in the perceived applicability of stereotype content as a function of comparative context and trait favourableness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 34 (2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01054.x .

Hassel, S., & Ridout, N. (2018). An investigation of first-year students’ and lecturers’ expectations of university education. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02218 .

McFarlane Shore, L., & Tetrick, L. E. (1994). The psychological contract as an explanatory framework in the employment relationship. In C. L. Cooper & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Trends in organizational behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 91–109). New York: John Wiley.

Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22 (1), 226–256.

Naylor, R. (2017). First year student conceptions of success: What really matters? Student Success, 8 , 9+.

Naylor, R., & Mifsud, N. (2019). Towards a structural inequality framework for student retention and success. Higher Education Research & Development, 1–14, . https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1670143 .

Nicholson, L., Putwain, D., Connors, L., & Hornby-Atkinson, P. (2013). The key to successful achievement as an undergraduate student: confidence and realistic expectations? Studies in higher education, 38 (2), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.585710 .

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: a study of psychological contracts. Journal of organizational behavior, 11 (5), 389–400.

Schalk, R., & Roe, R. E. (2007). Towards a dynamic model of the psychological contract. Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 37 (2), 167–182.

Social Research Centre. (2019). 2018 Student experience survey national report . Australia: Commonwealth of Australia.

Stok, F. M., & de Ridder, D. T. (2019). The focus theory of normative conduct. In K. Sassenberg & M. Vliek (Eds.), Social Psychology in Action (pp. 95–110). Cham: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Troiano, H., & Elias, M. (2014). University access and after: explaining the social composition of degree programmes and the contrasting expectations of students. Higher Education, 67 (5), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9670-4 .

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2010). Beyond hard outcomes: ‘soft’outcomes and engagement as student success. Teaching in Higher Education, 15 (6), 661–673.

Download references

This work was supported by a Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Grant from La Trobe University and funding from the School of Life Sciences and Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sydney School of Health Sciences, the University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Ryan Naylor

Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution, College of Science, Health and Engineering, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Fiona L. Bird & Nicole E. Butler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ryan Naylor .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Naylor, R., Bird, F.L. & Butler, N. Academic expectations among university students and staff: addressing the role of psychological contracts and social norms. High Educ 82 , 847–863 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00668-2

Download citation

Accepted : 15 December 2020

Published : 30 January 2021

Issue Date : November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00668-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Expectations

- Psychological contracts

- Social norms

- Qualitative analysis

- Student success

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

Published on September 7, 2022 by Tegan George and Shona McCombes. Revised on November 21, 2023.

The introduction is the first section of your thesis or dissertation , appearing right after the table of contents . Your introduction draws your reader in, setting the stage for your research with a clear focus, purpose, and direction on a relevant topic .

Your introduction should include:

- Your topic, in context: what does your reader need to know to understand your thesis dissertation?

- Your focus and scope: what specific aspect of the topic will you address?

- The relevance of your research: how does your work fit into existing studies on your topic?

- Your questions and objectives: what does your research aim to find out, and how?

- An overview of your structure: what does each section contribute to the overall aim?

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to start your introduction, topic and context, focus and scope, relevance and importance, questions and objectives, overview of the structure, thesis introduction example, introduction checklist, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about introductions.

Although your introduction kicks off your dissertation, it doesn’t have to be the first thing you write — in fact, it’s often one of the very last parts to be completed (just before your abstract ).

It’s a good idea to write a rough draft of your introduction as you begin your research, to help guide you. If you wrote a research proposal , consider using this as a template, as it contains many of the same elements. However, be sure to revise your introduction throughout the writing process, making sure it matches the content of your ensuing sections.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Begin by introducing your dissertation topic and giving any necessary background information. It’s important to contextualize your research and generate interest. Aim to show why your topic is timely or important. You may want to mention a relevant news item, academic debate, or practical problem.

After a brief introduction to your general area of interest, narrow your focus and define the scope of your research.

You can narrow this down in many ways, such as by:

- Geographical area

- Time period

- Demographics or communities

- Themes or aspects of the topic

It’s essential to share your motivation for doing this research, as well as how it relates to existing work on your topic. Further, you should also mention what new insights you expect it will contribute.

Start by giving a brief overview of the current state of research. You should definitely cite the most relevant literature, but remember that you will conduct a more in-depth survey of relevant sources in the literature review section, so there’s no need to go too in-depth in the introduction.

Depending on your field, the importance of your research might focus on its practical application (e.g., in policy or management) or on advancing scholarly understanding of the topic (e.g., by developing theories or adding new empirical data). In many cases, it will do both.

Ultimately, your introduction should explain how your thesis or dissertation:

- Helps solve a practical or theoretical problem

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Builds on existing research

- Proposes a new understanding of your topic

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Perhaps the most important part of your introduction is your questions and objectives, as it sets up the expectations for the rest of your thesis or dissertation. How you formulate your research questions and research objectives will depend on your discipline, topic, and focus, but you should always clearly state the central aim of your research.

If your research aims to test hypotheses , you can formulate them here. Your introduction is also a good place for a conceptual framework that suggests relationships between variables .

- Conduct surveys to collect data on students’ levels of knowledge, understanding, and positive/negative perceptions of government policy.

- Determine whether attitudes to climate policy are associated with variables such as age, gender, region, and social class.

- Conduct interviews to gain qualitative insights into students’ perspectives and actions in relation to climate policy.

To help guide your reader, end your introduction with an outline of the structure of the thesis or dissertation to follow. Share a brief summary of each chapter, clearly showing how each contributes to your central aims. However, be careful to keep this overview concise: 1-2 sentences should be enough.

I. Introduction

Human language consists of a set of vowels and consonants which are combined to form words. During the speech production process, thoughts are converted into spoken utterances to convey a message. The appropriate words and their meanings are selected in the mental lexicon (Dell & Burger, 1997). This pre-verbal message is then grammatically coded, during which a syntactic representation of the utterance is built.

Speech, language, and voice disorders affect the vocal cords, nerves, muscles, and brain structures, which result in a distorted language reception or speech production (Sataloff & Hawkshaw, 2014). The symptoms vary from adding superfluous words and taking pauses to hoarseness of the voice, depending on the type of disorder (Dodd, 2005). However, distortions of the speech may also occur as a result of a disease that seems unrelated to speech, such as multiple sclerosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

This study aims to determine which acoustic parameters are suitable for the automatic detection of exacerbations in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by investigating which aspects of speech differ between COPD patients and healthy speakers and which aspects differ between COPD patients in exacerbation and stable COPD patients.

Checklist: Introduction

I have introduced my research topic in an engaging way.

I have provided necessary context to help the reader understand my topic.

I have clearly specified the focus of my research.

I have shown the relevance and importance of the dissertation topic .

I have clearly stated the problem or question that my research addresses.

I have outlined the specific objectives of the research .

I have provided an overview of the dissertation’s structure .

You've written a strong introduction for your thesis or dissertation. Use the other checklists to continue improving your dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. & McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/introduction-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write an abstract | steps & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Rationale Essay

Writing about academic expectations.

The discussion of how you’re addressing ESC Area of Study Guidelines and other academic expectations is one of the most important in the rationale essay, as it presents your evidence, backed up by research, to show that your individually-designed degree is academically valid. Above all, think of this section as your logical argument for the validity of your degree choices. Provide enough specific evidence so that your readers (members of an academic review committee) will be convinced that you’ve

- done your research,

- understood your research, and

- addressed Empire State College and overall academic expectations thoughtfully and thoroughly.

As you start writing about academic expectations, make sure to name your area of study and concentration (if you have a degree with a concentration) so that there’s a clear relationship between the focus of your degree and your discussion of ESC guidelines.

Writing about Guidelines

- Name of your area of study and concentration (if you have a degree with a concentration).

- Include a summary or paraphrase, or even a list of the appropriate Empire State College Area of Study guidelines, to show that you understand the college’s general academic expectations for your type of degree. If you are using a guideline that has both a general discussion of expected skills and knowledge areas, plus a specific discussion of expected skills and knowledge for a specific concentration, you need to include a discussion of both the general and specific guidelines.

- Document by citing the pages.

- Analyze the contents of your own degree/concentration by explaining courses, PLA areas, and/or experience that you have (but did not pursue for PLA) that address the college-level knowledge expectation for each of the main items in the guideline/s.

Business, Management, and Economics

One of the ESC general guidelines for Business, Management, and Economics states this college-level knowledge expectation:

Ethical and social responsibility : demonstration of an understanding of and appreciation for ethical and social issues facing organizations and their environments

You may be planning to pursue credit through prior learning assessment in human resource management, and a good portion of your learning may have been about ethical issues within organizations, so you explain this briefly in this section of your rationale essay. Or you may plan to address this guideline by taking a course in Business Ethics. Or you may be doing a business degree focused on information technology, and plan on doing a course in Social and Ethical Issues in IT. There’s no one way to address this particular guideline; you just need to analyze the knowledge you already have or intend to gain through a course, in order to address this guideline and prove that you have this type of knowledge, in some way.

Community and Human Services

One of the ESC general guidelines for degrees in Community and Human Services states this college-level knowledge expectation:

Knowledge of human behavior: Students should identify and demonstrate an understanding of human behavior within the context of various social, developmental, global, economic, political, biological and/or environmental systems. These studies should cover theory, historical and developmental perspectives.

For example, studies could include human development, fire-related human behavior, child development, deviant behavior, stress in families, or cognitive psychology.

This guideline provides some ideas for courses or PLA areas; there are others as well, such as Introduction to Psychology, Child Development, and more. There is no one way to address this guideline.

Cultural Studies

One of the ESC specific concentration guidelines for a concentration in Communications states this college-level knowledge expectation:

History: a knowledge of the history and associated politics of media institutions/industries in a culture; knowledge of the role of media in culture/society, democracy and the development of digital identity

You may be planning to show that you have some historical knowledge of communications through a course in History and Theory of New Media, The American Cinema, The Decline of Journalism, or any of many other possibilities. Again, there is no one way to address this guideline.

Writing about General Education Requirements

Writing about general education requirements can be quite brief; a paragraph can suffice. SUNY requires at least 30 credits in 7 of 10 general education areas. (Two required general education areas are math and basic communication; the other 5 are your choice). Explain the areas you’ve included and give one example of a course that fulfills general education fully for each area.

Writing about Additional Academic Expectations

Did you summarize your research into other colleges (if needed) to show that you understand the general academic expectations for your type of degree? Have you found through your research that most degrees in your field include a course in X, even though the ESC guidelines do not explicitly state that area? Include a summary of your research into other colleges, as appropriate, if you needed to look at multiple programs to get a better sense of how to structure your own, and explain how your research translated into coursework for your degree.

Writing about Concentration Design (as appropriate)

In addition to your discussion of guidelines, your writing about academic or educational expectations may explain the overall pattern of your degree. Do you have courses that link with one another and fit into an overall framework? If appropriate, explain how you designed your concentration to move from introductory- to advanced-level studies, to include supportive studies that the guidelines do not mention but that are important to your individual goals, and/or to address the reasons why you designed your concentration in a particular, unique way. Some degrees do not need full, or any, explanation of concentration design, particularly if they follow a traditional, disciplinary route. Other degrees, such as degrees in the Interdisciplinary Area of Study, always need explanation of concentration design, because they allow so much flexibility. Academic review committee members need to understand why these degrees have been designed in certain ways, to include certain courses in certain patterns and sequences.

Answer the following questions to help address degree structure and design in your rationale essay:

- Does learning, especially in your concentration, show progression from introductory to advanced (in a bachelor’s degree concentration)?

- Do you have certain groups of courses that link with each other, for a particular purpose?

- Do you have certain courses that support and/or enhance one another (e.g., do some pieces of the general learning relate to and enhance studies in the concentration)?

- Writing about Academic Expectations. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Project : Educational Planning. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- image of open book with letters flying from it. Authored by : Mediamodifier. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/literature-book-page-clean-3033196/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2024

Exploring the roles of academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, and academic resilience on perceived English proficiency

- Po-Chi Kao 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 158 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

675 Accesses

Metrics details

This study aims to examine and analyze a research model comprising three latent variables (academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, and academic resilience) to gain insights into the perceived English proficiency of EFL (English as a foreign language) learners. These variables have been overlooked in previous literature despite their importance in understanding learning outcomes. A total of 395 undergraduate students from a Taiwanese university participated in this study. Through the use of structural equation modeling, the hypotheses in the research model were tested. The findings of this research are as follows: (1) Academic expectation stress has a significant and negative impact on EFL learners’ perceived English proficiency; (2) Academic resilience positively predicts EFL learners’ perceived English proficiency; (3) Academic resilience mediates the relationship between academic expectation stress and perceived English proficiency; (4) Adaptive coping mediates the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience. These results add valuable insights to the existing literature in EFL teaching and learning, shedding light on the dynamics of these variables.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The quest of English proficiency for EFL (English as a foreign language) learners can be a difficult road fraught with challenges. Academic expectation stress and academic resilience stand out as elements that are likely to influence students’ learning performance among these obstacles [ 1 , 2 ]. Adaptive coping may also play a role [ 3 ]. Academic expectation stress is defined as the psychological strain experienced by students due to the demanding nature of academic expectations imposed upon them [ 6 ]. Academic resilience is defined as the capacity of students to successfully deal with difficulties, setbacks, and stressors while retaining a positive outlook, adaptability and perseverance [ 9 ]. Adaptive coping is defined as the proactive approach of actively taking actions to eliminate or overcome stressors and reduce their impact [ 3 ]. The purpose of this study is to investigate and analyze the complex relationship between academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, academic resilience, and perceived EFL proficiency. The author hopes that this study will shed insight on the underlying mechanisms of latent variables that may affect students’ EFL learning outcomes directly or indirectly.

As the importance of mastering English in today’s society is widely acknowledged, the interplay of psychological factors and language acquisition is becoming an important research area in the study of psychology and language education. While previous researchers have made attempts to investigate the dynamics of psychological factors and language learning, there are still novel factors to explore, particularly to test if these factors can contribute to or impede the development of English proficiency. By delving into the exploration of these latent variables, this study seeks to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of language learning.

Moreover, this study goes beyond a unidimensional examination of individual factors and instead explores the synergistic dynamics of these factors. By doing so, this study offers a richer perspective on the mechanisms shaping EFL learning outcomes, thereby advancing the current understanding in this field. By understanding the issues faced by EFL learners in their quest for English proficiency, this study can ultimately contribute to the development of more effective pedagogical approaches in language education.

Literature review

In light of the significance of enhancing English proficiency among EFL learners, this study reviewed previous research and theoretical frameworks, aiming to examine the above-mentioned underlying variables that may shape and influence perceived English proficiency among EFL learners. Through the review and discussion of relevant literature in the following sections, the author aspired to illuminate the complex pathways that may underlie EFL learners’ journey towards English mastery.

- English proficiency

In today’s globalized world, English ability has become a vital asset. It provides individuals with educational, professional, and business opportunities, allowing them to succeed in an interconnected society. Mastery of the English language allows people to converse effectively with others from various backgrounds and improves intercultural understanding. English proficiency has become a precondition for success and upward mobility as it continues to dominate professions such as science, technology, commerce, and academia [ 4 ]. By understanding the importance of English competence and the elements that influence it, EFL learners can realize their full potential brought by mastering the English language.

In light of the significance of enhancing English proficiency among EFL learners, this research project aims to investigate the impact of underlying variables that have received limited attention in prior language education studies. Additionally, this study responds to the call made by Gardner [ 5 ] to explore novel variables in research on foreign language teaching and learning. Building upon previous research, this study introduces a conceptual framework comprising three factors that could have a direct or indirect influence on the perceived English proficiency of EFL learners. These latent factors include academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, and academic resilience.

- Academic expectation stress

Academic expectation stress refers to the psychological strain experienced by students due to the demanding nature of academic expectations imposed upon them [ 6 ]. Teachers, parents, classmates, or even self-imposed pressures can all contribute to these expectations [ 7 ]. Fear of failure, the quest of high grades, competition, and the need to satisfy social or personal success criteria are all common causes of stress [ 4 ]. These expectations can be overwhelming, resulting in anxiety, self-doubt, and a lower feeling of well-being [ 6 ].

Academic expectation stress can have a substantial impact on students’ learning experiences. Excessive or chronic stress inhibits cognitive functioning, impairs attention and concentration, and disturbs memory processes [ 8 ], all of which are necessary for EFL learning. Students may also suffer diminished motivation, lower interest in learning activities, and a drop in academic achievement [ 8 ]. As a result, its negative consequences on academic performance might create a downward spiral, exacerbating EFL learners’ English learning challenges.

- Adaptive coping

Students may use a variety of coping mechanisms to overcome stressful situations when faced with academic expectation stress. Adaptive coping is one such strategy. It refers to the proactive approach of actively taking actions to eliminate or overcome stressors and reduce their impact [ 3 ]. Active and planning tactics are used in adaptive coping [ 3 ]. The active method entails taking the initiative to tackle challenges, make efforts, and systematically implement coping techniques [ 3 ]. The cognitive process of considering how to successfully deal with a stressor is referred to as planning. It comprises devising action-oriented plans, deliberating on the essential measures to solve the issue, and deciding the best strategy to deal with the situation [ 3 ]. Adaptive coping represents a coping approach that places great importance on assuming control and actively tackling stressors. It entails acknowledging the presence of stress, comprehending its nature and consequences, and purposefully taking measures to mitigate and conquer it [ 3 ]. The strategies employed in adaptive coping concentrate on effectively addressing the underlying causes of stress, while simultaneously cultivating the necessary skills to triumph over challenges. This method fosters a sense of self-assurance, fortitude, and personal empowerment when confronted with adversity [ 3 ].

- Academic resilience

Academic resilience is the capacity of students to successfully deal with difficulties, setbacks, and stressors while retaining a positive outlook, adaptability and perseverance [ 9 ]. Self-belief, self-control, optimism, and a growth mindset are among the psychological qualities possessed by resilient students [ 10 ]. Academic resilience can be nurtured and developed through supportive environments, healthy relationships, and targeted interventions [ 9 ].

Students who are resilient are more inclined to uphold a balanced outlook, establish objectives that are attainable, and tackle obstacles with a proactive mindset for finding solutions [ 11 ]. According to Martin & Marsh [ 12 ], academic resilience enables students to recover from setbacks and embrace efficient study techniques, resulting in enhanced scholastic achievements and a more gratifying learning journey.

Rationale for the study

The literature review exposes a research gap in terms of limited attention to certain variables in the context of language education. Prior literature elucidates the detrimental effects of academic expectation stress on students’ learning experiences and academic achievement. Excessive stress can disrupt cognitive functioning, impair attention, and disturb memory process, which in turn may adversely affect EFL learning. Understanding the impact of academic expectation stress on language learners is crucial for effective language instruction. In addition, previous literature also highlights the significance of adaptive coping and academic resilience. Adaptive coping strategies, as mentioned, are crucial for addressing stressors and assuming control. Academic resilience, with its emphasis on a positive outlook, adaptability, and perseverance, plays a pivotal role in students’ ability to recover from setbacks and enhance their learning performance. While existing research has laid a strong foundation for understanding these factors respectively, there’s a need to delve deeper into the associations between these factors and English proficiency. The associations between these variables have received limited attention in prior research on language education. This research intends to bridge this gap by investigating these variables and their potential influence on English proficiency. In particular, the present study aligns with the call made by Gardner [ 5 ] to explore novel variables in research on foreign language teaching and learning. By introducing a conceptual framework that incorporates these understudied factors, the research responds to the academic community’s call for a deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of language learning. The research also seeks to address the identified research gap and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics involved in EFL learning. This knowledge will not only contribute to the field of language education but also benefit pedagogical practices that support learners in their pursuit of English proficiency.

From the perspective of the Self-determination Theory (SDT) by Ryan and Deci [ 13 ], psychological needs can affect people’s behavior and well-being. Individuals have the psychological needs of autonomy and competence, according to SDT [ 13 ]. English proficiency can be viewed as a vehicle through which students satisfy their competence need. The mastery of a language is a demonstration of competence, providing individuals with the ability to navigate an interconnected world. Academic expectation stress from teachers, parents, or peers may compromise students’ autonomy. The proactive nature of adaptive coping aligns with SDT’s emphasis on autonomy. In actively addressing stressors and taking control of the coping process, students are fulfilling their need for autonomy. Academic resilience, characterized by a positive outlook, adaptability, and perseverance, resonates with SDT’s emphasis on psychological well-being. As a research gap in understanding the underlying mechanisms of latent variables that may directly or indirectly impact students’ EFL learning outcomes has been identified, this research introduced and tested a novel conceptual framework inspired by the theoretical perspective of SDT. Ultimately, this study aims to address the identified gap and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing EFL learning outcomes.

Theoretical underpinnings and hypothesis development

Academic expectation stress and learning outcomes.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, proposed by Lazarus and Folkman [ 14 ], offers valuable insights into the relationships between academic expectation stress and learning outcomes. Lazarus and Folkman [ 14 ] assert that individuals evaluate stressors based on their cognitive appraisal, which comprises primary and secondary appraisals. Primary appraisal involves assessing the significance of the stressor, while secondary appraisal focuses on one’s ability to cope with it. In the context of academic expectation stress, students often appraise the stressor as significant and may question their ability to cope. According to Ang and Huan [ 15 ], this self-doubt can impair cognitive function, lessen their willingness to make efforts or engage, and ultimately have an effect on their learning outcomes. This self-doubt, combined with the emotional responses triggered by academic stress, can hinder concentration, information processing, and overall cognitive functioning [ 16 ]. This study therefore hypothesizes that academic expectation stress has a negative impact on EFL learners’ English proficiency. (Hypothesis 1)

Academic resilience and learning outcomes

The relationships between academic resilience and learning outcomes can be explained with the Social Cognitive Theory [ 17 ]. The reciprocal interactions between people, the environment, and behaviors are highlighted in the Social Cognitive Theory. This theory contends that motivation, perseverance, and academic success are all greatly influenced by self-efficacy, or people’s perceptions of their capacity to complete particular tasks or goals.

Academic resilience, which involves students’ capacity to successfully navigate academic difficulties, setbacks, and stressors while maintaining a positive attitude and perseverance [ 18 ], is closely related to self-efficacy. According to Cassidy [ 18 ], students with high levels of academic resilience are more likely to have a strong sense of self-efficacy, which can affect their motivation to work hard, persevere in the face of challenges, and use effective learning strategies. Improved learning outcomes may result from this increased motivation and engagement.

Additionally, social modeling and observational learning are emphasized in the Social Cognitive Theory [ 19 ]. Students with high academic resilience may observe and model the behaviors of resilient peers, teachers, or mentors. By witnessing others’ successful efforts to overcome obstacles, students can develop self-efficacy beliefs and ultimately enhance their learning outcomes. Hence, this study hypothesizes that academic resilience positively predicts EFL learners’ English proficiency. (Hypothesis 2)

Academic resilience as a mediator between academic expectation stress and academic performance

The Resilience Theory [ 20 ] offers valuable theoretical perspectives to explore how academic resilience may influence students’ ability to navigate stress and achieve optimal academic performance. The Resilience Theory [ 20 ] posits that individuals can adapt, thrive, and maintain positive functioning despite adversity. It emphasizes the dynamic process through which individuals harness their internal and external resources to cope with stress and overcome challenges. Resilience is not a fixed trait, but rather a malleable quality that can be fostered and developed [ 9 ].

Academic resilience may be crucial in mediating the connection between stress and academic performance in the context of learning. Academic resilience refers to a student’s capacity to overcome obstacles, stay motivated, and persevere [ 10 ]. Academic resilience can act as a protective factor and affect students’ academic performance when they are under high levels of academic expectation stress. Additionally, their resilience can mitigate the detrimental effects of stress on academic performance. Resilient students are more likely to see academic difficulties as growth opportunities rather than insurmountable obstacles. They view failures as temporary setbacks and maintain confidence in their abilities to overcome them [ 9 ]. This positive outlook and belief may ultimately lead to improved academic performance. Hence, this study hypothesizes that academic resilience mediates the relationship between academic expectation stress and EFL proficiency. (Hypothesis 3)

Adaptive coping as a mediator between academic expectation stress and academic resilience

The Cognitive-behavioral Theory [ 21 ] may illuminate the mediating role of adaptive coping in the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience. The Cognitive-behavioral Theory emphasizes the interplay between individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviors [ 21 ]. This theory posits that individuals’ thoughts and interpretations of events significantly influence their emotional and behavioral responses. By recognizing and modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors, individuals can enhance their well-being and cope with stressors more effectively [ 21 ].

In the context of academic expectation stress and academic resilience, adaptive coping can be viewed through the lens of the Cognitive-behavioral Theory. Students who engage in adaptive coping strategies actively challenge and reframe negative thoughts and beliefs associated with academic expectation stress. They may replace self-defeating thoughts with more adaptive and empowering thoughts.

By adaptively challenging and modifying their thoughts, students can regulate their emotional responses to academic expectation stress, reducing anxiety, and increasing their resilience. These cognitive changes can lead to adaptive behaviors in the face of challenges, ultimately enhancing their academic resilience. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that adaptive coping mediates the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience. (Hypothesis 4)

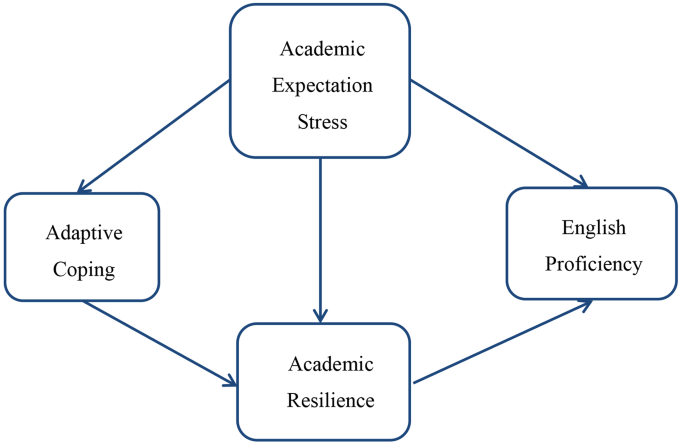

The four hypotheses are conceptualized as a research model as shown in Fig. 1 . Four variables — academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, academic resilience, and perceived English proficiency — are examined in relation to one another in this study. Understanding how these factors interact and affect one another is the objective of the present study. This study aims to offer empirical evidence that quantifies the dynamics of these four variables by using a cross-sectional design in an EFL classroom setting at a university.

Conceptual framework

In order to examine the hypotheses and achieve the research objectives, this study employed a non-experimental research design to collect quantitative data. The study adopted a cross-sectional approach, engaging the involvement of college students who are currently enrolled in EFL courses. These students were invited to partake in a survey. The variables of interest were assessed through self-report measures, providing the participants with an opportunity to give their responses.

Participants

The sample consisted of 395 young adults who are currently enrolled in EFL courses offered by a university in Taiwan, including 200 females (50.6%) and 195 males (49.4%). The participants had four age groups, 150 of them belonged to the category of 18 years old (38%), 199 students belonged to 19 years old (50.4%), 26 students belonged to 20 years old (6.6%), while 20 students belonged to the age category of 21 years old or above (5%). Notably, the majority of the participants belonged to the 18–19 age groups, accounting for approximately 90% of the total sample.

The study and the survey process were thoroughly explained to the EFL students before they took part in the survey. Consent forms were provided to inform the students about the goals of the current research project and to invite their participation. It was emphasized that the research data would be kept confidential for research purposes only and that their responses would not have an impact on their course scores. The students were given the freedom that they could end the survey at any time. All data collected were anonymous, and it took students approximately 20 min to complete the entire survey. The research qualifies as being exempt from ethical approval because it involves the use of non-sensitive, completely anonymous educational survey when the participants are not defined as “vulnerable” and participation does not induce undue psychological stress or anxiety. It is worth noting that this study followed the ethical guidelines established by the university.

The Academic Expectation Stress Inventory (AESI) developed by Ang and Huan [ 15 ] consisting of nine items was used to measure the extent of academic stress resulting from personal expectations as well as those of parents and teachers. Each item in the scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never True) to 5 (Almost Always True). The total scores obtained from summing the item responses indicate the level of academic expectation stress, with higher scores indicating higher levels of stress. Ang and Huan [ 15 ] have established the AESI as a valid and reliable tool that has been successfully used among the adult population. This scale has been reported to possess good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) [ 15 ].

Adaptive coping strategies were assessed with the Adaptive Coping Scale (ACS) [ 3 ], which was derived from the active coping and planning subscales of the Coping Behavior Questionnaire (COPE) [ 3 ]. In the original study validating the COPE scale [ 3 ], the two subscales of Active Coping and Planning were found to converge into a single factor “adaptive coping”. Similar to the study by Thompson et al. [ 22 ], the author of the present study combined these two subscales to evaluate what was referred to as adaptive coping in this study. Students were asked to recall how they coped with academic expectation stress and rate each item on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I usually don’t do this at all) to 4 (I usually do this a lot). A sample statement is “I take direct action to get around the problem.” Internal consistency for this scale has been reported to be α = 0.93 [ 22 ].

The Academic Resilience Scale (ARS) [ 9 ] was used to assess students’ capacity to proficiently handle setbacks, challenges, adversities, and pressures encountered within an academic environment. This scale has six items, and each of them is worded in a positive sense on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Never True) to 5 (Almost Always True). A sample item is “I’m good at bouncing back from a poor mark in my schoolwork.” This scale has been reported to possess good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) [ 9 ].

The participants’ perceived English proficiency was assessed using the Self-reported English Proficiency Scale (SEPS) [ 23 ], which consists of 12 items. This scale was developed based on previous studies conducted by Butler [ 24 ] and Chacon [ 25 ]. Participants rated each statement on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score indicates a higher level of perceived English proficiency. An example item from the scale is “In face-to-face interaction with an English speaker, I can participate in a conversation at a normal speed.” The SEPS has demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.85 [ 23 ].

Data analysis

This research involved an examination of demographic details, which are essential for testing the proposed relationships among study variables and validating theoretical propositions. To accomplish the objectives, SPSS v.27 was utilized.

To confirm that the collected data followed a normal distribution, values of skewness and kurtosis were examined and found to be approximately within the established criterions i.e., ± 1 or ± 2 [ 26 , 27 ]. Furthermore, multicollinearity was assessed, and all variables in the model displayed VIF values below 3, indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity [ 26 ]. Consistent with Kock’s [ 28 ] recommendation, VIF values below 3.3 suggest no common method bias. Descriptive analysis, employing mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), was conducted to assess the central tendency and variability of the responses. Additionally, correlations among the study variables were examined to evaluate the nature and strength of the interrelationships. See Table 1 for details on above.

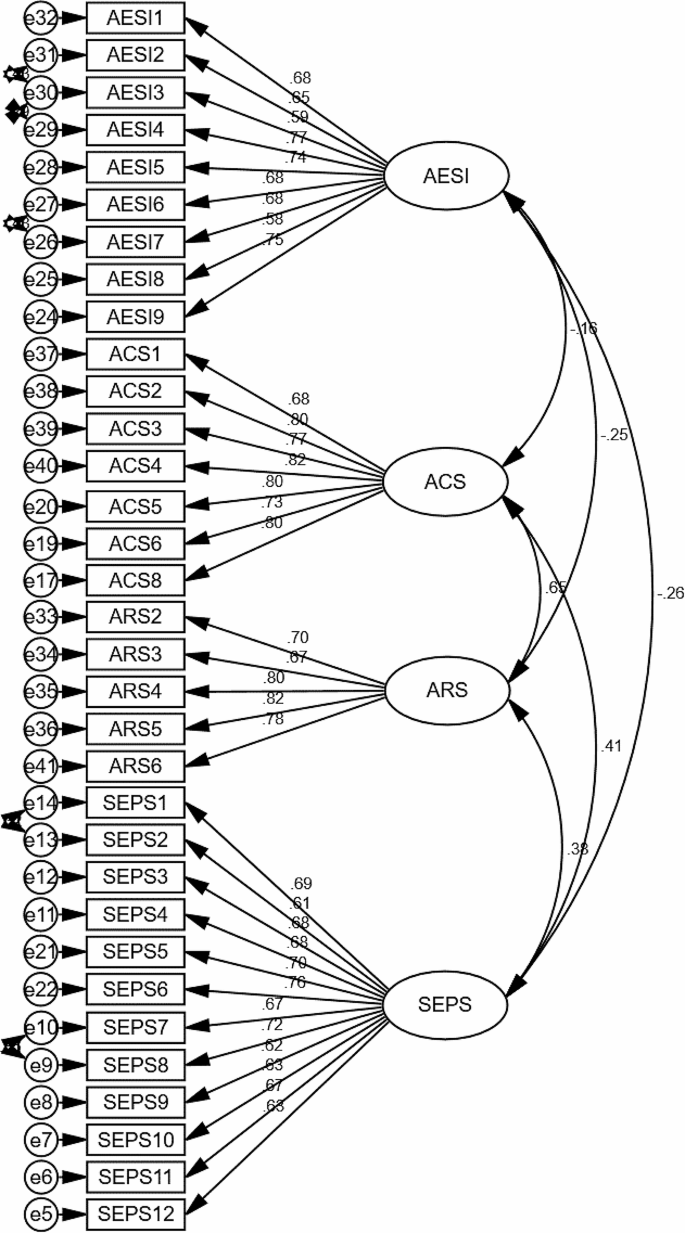

Assessment of measurement model

Evaluation of the measurement model was done to assess the reliability and validity of the study scales. AMOS v.24 was utilized for this purpose. A four-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the dimensionality and coherence of the ACS, AESI, ARS and SEPS factors [ 26 ]. In order to achieve the best possible fit between the data and the model, error terms were covariated based on modification index values exceeding 4 [ 26 , 29 ], as depicted in Fig. 2 . That four-factor model demonstrated a good fit, X 2 (984) / df (484) = 2.03 (< 3), RMR = 0.043 (< 0.08), TLI = 0.921 (> 0.90), CFI = 0.928 (> 0.90), and RMSEA = 0.051 (< 0.08). The acceptable criteria for these indices are provided in parentheses [ 26 ].

In addition to evaluating the model fitness indices, this study also ensured the reliability and validity of the measurement model through various additional procedures. Firstly, the factor loadings were examined, and items with factor loadings above 0.5 were kept (see Fig. 2 ). Cronbach’s alpha (CA) was also assessed, and all values exceeded 0.7, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. Composite reliability (CR) values were also above 0.7, further confirming the reliability of the measurement model. Convergent validity, assessed by the average variance extracted (AVE), exceeded 0.5 for all factors except for AESI and SEPS which had AVE values > 0.4. However, since their CR values were over 0.6, they were still considered acceptable [ 30 ].

Additionally, the study evaluated discriminant validity through the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, ensuring that all ratios were below 0.85 [ 26 ]. This analysis reinforced the appropriateness of the measurement model, establishing a strong foundation for hypothesis testing, as presented in Table 2 .

Measurement model diagram

Notes: ACS = Adaptive Coping Scale; AESI = Academic Expectation Stress Inventory; ARS = Academic Resilience Scale; SEPS = Self-reported English Proficiency Scale; circles = error terms; double-headed arrows = measurement error correlations

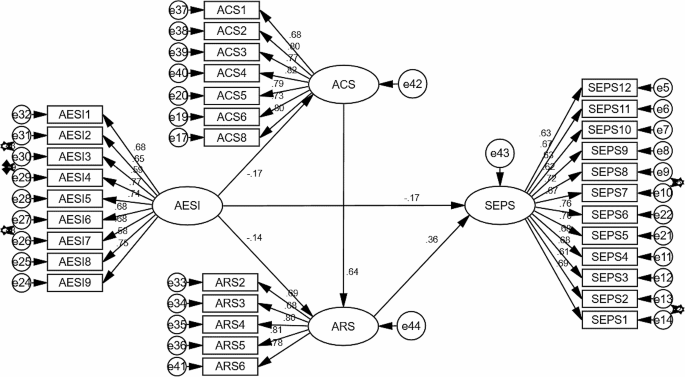

Assessment of structural model

Evaluation of the structural model (depicted in Fig. 3 ) was done to evaluate its fitness and facilitate hypothesis testing. Based on the model fitness indices, the four-factor structural model demonstrated a good fit, X 2 (1000) / df (485) = 2.06, RMR = 0.046, TLI = 0.919, CFI = 0.925, and RMSEA = 0.052 [ 26 ]. These results provided a strong basis for confidently testing the study’s hypotheses.

Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis testing was conducted using structural equation modelling, employing 2000 samples of bias-corrected bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals (CI) comprising lower bound (LB) and upper bound (UB). As illustrated in Table 3 , the results revealed that AESI had a negative and significant impact on SEPS (B = − 0.167, p =.014, 95% CI [-0.282, − 0.036]), which confirmed that H1 was supported. It was concluded that academic expectation stress had a significant and negative impact on EFL learners’ English proficiency. ARS had a positive and significant impact on SEPS (B = 0.359, p =.001, 95% CI [0.227, 0.471]). Therefore, H2 was supported. It was concluded that academic resilience positively predicted EFL learners’ English proficiency. AESI had a negative and significant impact on SEPS through ARS (B = − 0.047, p =.011, 95% CI [-0.097, − 0.009]). Thus, mediation occurred. H3 was also supported. It was concluded that academic resilience mediated the relationship between academic expectation stress and English proficiency. AESI had a positive and significant impact on ARS through ACS (B = − 0.102, p =.013, 95% CI [-0.192, − 0.024]). Hence, again mediation occurred, so H4 was also supported. It was concluded that adaptive coping mediated the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience.

Mediation analysis

While H3 was supported, the type of mediation was not determined based solely on the indirect effects. As indicated in Table 4 , the direct effect of AESI on SEPS was found to be significant (B = − 0.158, p =.012, 95% CI [-0.275, − 0.037]), suggesting a case of partial mediation [ 31 ]. When ARS was introduced into the equation, the direct effect was decreased to B = − 0.047, meaning that ARS was able to lessen the negative impact of AESI on SEPS by 77.07% (indirect effect divided by total effect– 1). Sobel’s [ 32 ] test demonstrated that the indirect effect of AESI on SEPS via ARS was significant (z = -2.62, p =.009), providing additional support for H3. Similarly, for H4 it was a partial mediation as direct effect was significant (B = − 0.158, p =.012, 95% CI [-0.275, − 0.037]). ACS was able to lessen the negative impact of AESI on ARS by 60.77%. Sobel test also found to be significant (z = -2.84, p =.005), so it provided an extended support to H4.

SEM path model

The statistical findings reveal that academic expectation stress negatively predicts the perceived English proficiency of EFL learners, while academic resilience has a positive effect on perceived English proficiency. Concurrently, the relationship between academic expectation stress and perceived English proficiency is partially mediated by academic resilience. This study also reveals the mediating role of adaptive coping in the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience. There has been a lack of research simultaneously exploring the interrelationships among these four variables in the existing literature. This study aims to fill this research gap by investigating their interconnectedness. While previous studies have primarily examined the individual links between these variables, this study stands out as one of the first to explore their simultaneous interplay. By doing so, it offers valuable quantitative evidence to deepen our understanding of these four variables within the research framework.

The statistical results revealed a significant negative effect of academic expectation stress on perceived English proficiency. There could be a couple of explanations for this finding. According to MacIntyre and Gregersen [ 33 ], high levels of academic stress may increase anxiety and have a negative impact, which can impede language learning. Academic expectation stress can negatively affect a learner’s capacity to learn and use English by impairing cognitive functioning, attentional focus, and information processing [ 15 ]. Stress can also make learners fear failure and create a tendency toward perfection [ 34 ]. Individuals who are burdened by intense academic expectations may find themselves compelled to meet or surpass these demands. Consequently, they may develop a predisposition to avoid errors rather than actively immerse themselves in purposeful language practice. The apprehension of failure can act as a hindrance to the acquisition of language, inhibiting learners from embracing challenges or experimenting with the language.

The analysis also unveiled a notable and beneficial impact of academic resilience on EFL learners’ perceived proficiency in the English language. This finding is similar to the results of previous studies [ 35 , 36 ]. Academic resilience refers to the ability to rebound from setbacks and maintain motivated in the face of challenges [ 12 ]. It appears that EFL learners who possess a greater level of resilience are more likely to persist and exert effort in their language learning endeavors, even when confronted with difficulties. This sustained effort and motivation may contribute to an increase in language practice and involvement, which can ultimately lead to an improvement in the learners’ English proficiency. Moreover, resilient learners tend to possess a favorable perception of their academic capabilities [ 18 ], even when faced with obstacles. Having a higher level of self-efficacy may result in a heightened confidence in English language skills and a willingness to take on demanding language tasks. This positive mindset and self-belief may enhance the engagement of EFL learners in their language learning journey and positively impact the outcomes of English learning.

The relationship between academic expectation stress and English proficiency being mediated by academic resilience was also revealed in this study. Resilient learners may lessen the negative effects of academic expectation stress on EFL proficiency and advance positive English learning outcomes because they are more likely to perceive academic expectations stress as manageable and respond with proactive and effective strategies [ 20 ]. Additionally, as was already mentioned, students who are resilient tend to believe they are capable of overcoming obstacles and succeeding [ 18 ]. As learners with higher resilience are more likely to maintain confidence in their language learning abilities and persevere in the face of challenges, this positive self-belief can serve as a buffer against the detrimental effects of academic expectation stress.

The relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience was found to be mediated by adaptive coping, according to the statistical analysis. This finding can be explained with the Cognitive-Behavioral Theory [ 21 ]. Students may actively challenge and reframe unfavorable ideas and beliefs about academic expectation stress when they use adaptive coping strategies. In this process, self-defeating thoughts are swapped out for stronger, more empowering ones. Students can control their emotional responses to academic expectation stress by actively addressing and moderating their thoughts, which lowers anxiety and boosts resilience. When confronted with academic expectation stress, these cognitive changes and adaptive behaviors may ultimately improve their academic resilience.

Implications

For EFL education, the finding that academic expectation stress has a significant negative impact on English proficiency has educational implications. This finding emphasizes the need to address academic expectation stress as a potential obstacle to English proficiency. Teachers might think about implementing student-centered approaches [ 37 ], which encourage a nurturing and supportive learning environment where students feel more empowered and less under pressure from their teachers, parents or themselves. EFL teachers can foster language learning by addressing academic expectation stress, as well as create an atmosphere conducive to language learning in order to better learners’ English proficiency.

The finding that academic resilience has a significant and positive impact on English proficiency emphasizes the importance of recognizing and fostering academic resilience in language learning. EFL instructors should think about incorporating practices and strategies that can improve students’ resilience, such as giving learners the chance to set goals and develop self-regulated learning strategies [ 38 ]. EFL instructors can help students overcome obstacles, stick with their language learning efforts, and ultimately raise their English proficiency by fostering academic resilience.

Pinpointing academic resilience as a mediator between the stress of academic expectations and English proficiency shows the significance of acknowledging and cultivating academic resilience as a crucial element in enhancing EFL proficiency. By fostering academic resilience, EFL educators can support students in effectively managing the pressures of academic expectations, ultimately resulting in enhanced EFL proficiency.

Similarly, the mediating role of adaptive coping in the relationship between academic expectation stress and academic resilience also carries implications for EFL education. To enhance learners’ academic resilience, EFL teachers can consider implementing interventions that help learners develop adaptive strategies such as active and planning approaches [ 3 ] to cope with academic expectation stress.

Limitations

Like any research, it is important to recognize certain limitations of this study. Firstly, the reliance on self-report measures to assess the four variables introduces the possibility of response bias. Future investigations could benefit from incorporating objective measures and employing diverse research methods to gauge these variables. Moreover, the specific focus on EFL learners within the Taiwanese tertiary educational context may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Replicating the study in various learner populations and educational settings would offer additional perspectives on the interrelationship of these variables among EFL learners. Finally, for future researchers, there are still a few less explored psychological factors that could potentially influence EFL learning experience. One such factor is transpathy [ 39 , 40 ]. It means the amount of emotional and sensory involvement of the teacher [ 39 , 40 ]. Transpathy may affect students’ EFL learning experience. By incorporating transpathy into EFL research, future researchers can advance the field’s understanding of the complex dynamics of psychological factors at play in foreign language teaching and learning.

Thus far, there has been a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the interplay between academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, academic resilience, and perceived English proficiency among university EFL learners. This study aims to fill this research gap and expand the current knowledge base in this particular population. Moreover, the findings of this research have significant implications for EFL teachers who strive to enhance their students’ English proficiency. The author anticipates that these findings will contribute to the existing literature in the fields of education and applied linguistics by providing a thorough examination of these variables among college students. By gaining deeper insights into these variables, university EFL learners can improve their English learning experiences, while EFL instructors can offer better support to their students in enhancing their English proficiency.

Data availability

All data collected is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Kao P-C. Medical students’ attention in EFL class: roles of academic expectation stress and quality of sleep. Appl Linguist Rev. 2021. Ahead of prints.

Yang S, Wang W. The role of academic resilience, motivational intensity and their relationship in EFL learners’ academic achievement. Front Psychol. 2022;12:823537.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(2):267–83.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ilyosovna NA. The importance of English language. Int J Orange Technol. 2020;2(1):22–4.

Google Scholar

Gardner RC. The socio-educational model of second language acquisition. In: Lamb M, Csizér K, Henry A, Ryan S, editors. The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. pp. 21–37.

Chapter Google Scholar

Poots A, Cassidy T. Academic expectation, self-compassion, psychological capital, social support and student wellbeing. Int J Educ Res. 2020;99:101506.

Article Google Scholar

Calaguas GM. Parents/teachers and self-expectations as sources of academic stress. Int J Res Stud Psychol. 2012;2(1):43–52.

Shek TL. Mental health of Chinese adolescents in different Chinese societies. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 1995;8(2):117–55.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Martin AJ, Marsh HW. Academic resilience and its psychological and educational correlates: a construct validity approach. Psychol Sch. 2006;43(3):267–81.

Rudd G, Meissel K, Meyer F. Measuring academic resilience in quantitative research: a systematic review of the literature. Educ Res Rev. 2021;34:100402.

Martin AJ, Burns EC, Collie RJ, Cutmore M, MacLeod S, Donlevy V. The role of engagement in immigrant students’ academic resilience. Learn Instr. 2022;82:101650.

Martin AJ, Marsh HW. Academic buoyancy: towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. J Sch Psychol. 2008;46(1):53–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;61:101860.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

Ang RP, Huan VS. Academic expectations stress inventory: development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66(3):522–39.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

McBride EE, Greeson JM. Mindfulness, cognitive functioning, and academic achievement in college students: the mediating role of stress. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:10924–34.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Asian J Soc Psychol. 1999;2(1):21–41.

Cassidy S. Resilience building in students: the role of academic self-efficacy. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1781.

Schunk DH. Social cognitive theory. In: Harris KR, Graham S, Urdan T, McCormick CB, Sinatra GM, Sweller J, editors. APA educational psychology handbook: vol 1. Theories, constructs, and critical issues. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 101–23.

VanBreda AD. Resilience theory: a literature review. South African Military Health Service; 2001.

Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):953–9.

Thompson RJ, Mata J, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Gotlib IH. Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: variations across age and depressive state. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(6):459–66.

Yilmaz C. Teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy, English proficiency, and instructional strategies. Soc Behav Pers. 2011;39(1):91–100.

Butler YG. What level of English proficiency do elementary school teachers need to attain to teach EFL? Case studies from Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. TESOL Q. 2004;38(2):245–78.

Chacón CT. Teachers’ perceived efficacy among English as a foreign language teachers in middle schools in Venezuela. Teach Teach Educ. 2005;21(3):257–72.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. Cengage; 2019.

George D, Mallery P. IBM SPSS statistics 27 step by step: a simple guide and reference. Routledge; 2021.

Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collaboration (ijec). 2015;11(4):1–10.

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge; 2016.

Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J Mark Res. 1981;18(3):382–8.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82.

Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312.

MacIntyre P, Gregersen T. Affect: the role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learning. In: Mercer S, Ryan S, Williams M, editors. Psychology for language learning: insights from research, theory and practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012. pp. 103–18.

Stoeber J, Rennert D. Perfectionism in school teachers: relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21(1):37–53.

Liu H, Zhong Y, Chen H, Wang Y. The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: a conservation-of-resources perspective. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2023-0089

Liu H, Han X. Exploring senior high school students’ English academic resilience in the Chinese context. Chin J Appl Linguistics. 2022;45(1):49–68.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Awla NJ, Haji NM. Investigating the implementation of student-centered approach in EFL speaking classroom. J Duhok Univ. 2023;26(1):750–67.

Mohan V, Verma M. Self-regulated learning strategies in relation to academic resilience. Voice Res. 2020;27:34.

Pishghadam R, Ebrahimi S, Rajabi Esterabadi A, Parsae A. Emotions and success in education: from apathy to transpathy. J Cogn Emot Educ. 2023;1(1):1–16.

Miri MA. (2023). Transpathy and the relational affect of social justice in refugee education. J Cogn Emot Educ. 2023;1(2):17–32.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The mode of data collections was conducted via Google forms thus no such funding was required for the present study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for General Education, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Po-Chi Kao .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

According to the Measures for the Ethics Review of Research Involving Human released by Taiwan authorities ( https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOMA/fp-2782-9538-106.html ), the ethics review of this study can be waived as the research involves the use of non-sensitive, completely anonymous educational survey when the participants are not defined as vulnerable. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the author’s institution. All participants were given a plain language statement and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The participants were assured of the right to confidentiality of information and the right to withdraw from the study at any stage of the research.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kao, PC. Exploring the roles of academic expectation stress, adaptive coping, and academic resilience on perceived English proficiency. BMC Psychol 12 , 158 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01630-y

Download citation

Received : 10 September 2023

Accepted : 27 February 2024

Published : 16 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01630-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- EFL education

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific