Title: The Failure of Governance in Nigeria: An Epistocratic Challenge

The failure of governance in Nigeria manifests in the declining capacity of political leaders to recognize systemic risks such as election fraud, terrorist attacks, herder-farmer conflict, armed banditry, and police brutality and put in place the necessary measures to navigate these challenges. In contrast with the current system in which leadership is attained through bribery, intimidation, and violence, Nigeria needs an epistocratic system of governance that is founded on the pedigree of its political leaders and the education of its voters.

At the end of the Cold War, African civil society movements striving for more democratic governance began to challenge authoritarian regimes on the continent. Declining living conditions within African countries and the failure of authoritarian African leaders to deliver the promises of economic prosperity they made to encourage the acceptance of development aid fueled the push for change. International donors’ insistence on democratic reform as a precondition for aid gave impetus for Nigerian civil society to push for domestic accountability. Thus, domestic pressure for political pluralism and external pressure for representative governance have both played a role in the calls for democratic reform in Nigeria.

But despite some successes, corruption and socioeconomic disparities within Nigerian democracy continue to run rampant. Since 1999, the democratic space has been dominated by political elites who consistently violate fundamental principles associated with a liberal democratic system, such as competitive elections, the rule of law, political freedom, and respect for human rights. The outcome of the 2019 presidential election further eroded public trust in the ability of the independent electoral commission to organize competitive elections unfettered by the authoritarian influences of the ruling class. This challenge is an indicator of the systemic failure in Nigeria’s governance system. A continuation of the current system will only accelerate the erosion of public trust and democratic institutions. In contrast with the current system in which votes are attained through empty promises, bribery, voter intimidation, and violence, Nigeria needs a governance system that will enhance the education of its voters and the capability of its leaders.

Statistically speaking, Nigeria has consistently ranked low in the World Governance Index in areas such as government effectiveness, political stability and the presence of violence and terrorism, rule of law, and control of corruption. Nigeria is perceived in the 2020 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index as a highly corrupt country with a score of 25/100 while its corruption ranking increased from 146 in 2019 to 149 in 2020 out of 180 countries surveyed. While President Muhammadu Buhari won the 2015 election on his promise to fight insecurity and corruption, his promises went unfulfilled; Boko Haram continues to unleash unspeakable violence on civilians while the fight against corruption is counterproductive.

At the core of Nigeria’s systemic failure is the crisis of governance, which manifests in the declining capacity of the state to cope with a range of internal political and social upheavals. There is an expectation for political leaders to recognize systemic risks such as terrorist attacks, herder-farmer conflict, and police brutality and put in place the necessary infrastructure to gather relevant data for problem solving. But the insufficiency of political savvy required to navigate the challenges that Nigeria faces has unleashed unrest across the nation and exacerbated existing tensions. The #ENDSARS Protests against police brutality in 2020 is one of the manifestations of bad governance.

The spiral of violence in northern Nigeria in which armed bandits engage in deadly planned attacks on communities, leading to widespread population displacement, has become another grave security challenge that has sharpened regional polarization. Because some public servants are usually unaware of the insecurities faced by ordinary Nigerians, they lack the frame of reference to make laws that address the priorities of citizens. The crisis of governance is accentuated by a democratic culture that accords less importance to the knowledge and competence that political leaders can bring to public office. These systemic challenges have bred an atmosphere of cynicism and mistrust between citizens and political leaders at all levels of government.

Political elites in Nigeria also exploit poverty and illiteracy to mobilize voters with food items such as rice, seasoning, and money. The rice is usually packaged strategically with the image of political candidates and the parties they represent. The assumption is that people are more likely to vote for a politician who influences them with food than one who only brings messages of hope. The practice of using food to mobilize voters is commonly described as “ stomach infrastructure ” politics. The term “stomach infrastructure” arose from the 2015 election in Ekiti state when gubernatorial candidate Ayodele Fayosi mobilized voters with food items and defeated his opponent Kayode Fayemi. It is undeniable that Nigerian political culture rewards incompetent leaders over reform-minded leaders who demonstrate the intellectualism and problem-solving capabilities needed to adequately address systemic issues of poverty and inequality.

Jason Brennan describes the practice of incentivizing people to be irrational and ignorant with their votes as the unintended consequence of democracy. Brennan believes specific expertise is required to tackle socio-economic issues, so political power should be apportioned based on expert knowledge. As Brennan suggests, Nigeria lacks a system of governance in which leadership is based on capability. Rather, the political system in Nigeria is dominated by individuals who gain power through nepotism rather than competence, influence voters with food rather than vision, and consolidate power through intimidation or by incentivizing constituents with material gifts which they frame as “empowerment” to keep them subservient and loyal political followers. By implication, the failure of governance in Nigeria is arguably the result of incompetent leadership.

Nigeria needs a new model of governance in which political leadership is based on the knowledge and competence of both political leaders and the electorate. One solution is to establish what Brennan refers to as epistocracy , which is a system of governance in which the votes of politically informed citizens should count more than the less informed. For J ustin Klocksiem , epistocracy represents a political system in which political power rests exclusively on highly educated citizens. This idea drew its philosophical influence from John Stuart Mill , who believed that the eligibility to vote should be accorded to individuals who satisfy certain educational criteria. The notion that educational attainment should be the prerequisite for the electorate to choose their leaders as proposed by Brennan, Klocksiem, and Mill is an important proposition that should be taken seriously.

However, one cannot ignore that such thinking originates from societies where civic education is high and the electorate can make informed choices about leadership. In Nigeria, the majority of citizens are uneducated on political issues. Simultaneously, those who are highly educated are increasingly becoming indifferent to political participation; they have lost faith in the power of their votes and the integrity of the political system. For an epistocratic system to work in Nigeria, there must be significant improvements in literacy levels so that citizens are educated about the issues and can use their knowledge to make informed decisions about Nigeria’s political future.

It is important to mention that Nigeria’s political elites have exploited illiteracy to reinforce ethnic, religious, and political divisions between groups that impede democratic ideals. Since the resultant effect of epistocracy is to instill knowledge, raise consciousness and self-awareness within a polity anchored on the failed system of democracy, decisions that promote the education of uninformed voters are the rationale for an epistocratic system of governance. The Constitution must ensure that only citizens who can formulate policies and make informed decisions in the public’s best interest can run for public office. When the Constitution dictates the standard of epistocratic governance, informed citizens will be better equipped to champion political leadership or determine the qualifications of their leaders. Epistocratic governance will be the alternative to Nigeria’s current dysfunctional democratic system while retaining the aspects of liberal democracy that maintain checks and balances.

We are not, however, oblivious that implementing such an epistocratic system of governance in Nigeria potentially contributes to more inequality given its highly undemocratic and exclusive nature. Our argument takes into consideration the contextual realities of poverty and illiteracy and the realization that poor and illiterate constituents have less power to evaluate the credibility of public servants or hold them accountable. The benefits of electing epistocratic leaders are that many citizens would desire to be educated in preparation for leadership. The more educated the population the more likely it is that political leaders will be held accountable. However, the kind of education that is needed to significantly transform the governance landscape in Nigeria is civic education.

We propose three policies to promote epistocratic governance in Nigeria. First, aspiring leaders must demonstrate the intellectual pedigree to translate knowledge into effective, transparent, and accountable governance that leads to national prosperity. As Rotimi Fawole notes, the bar should be higher for those aspiring to executive or legislative office “to improve the ideas that are put forward and the intellectual rigor applied to the discussions that underpin our statehood.”

Second, the government must increase access to education through government-sponsored initiatives that integrate civic education into school curriculums. Currently, little opportunity exists for young Nigerians, particularly those in underfunded public education systems, to learn about their civic roles at the local, state, national, and international levels, including how to emerge as participating citizens through the academic curriculum.

Third, the government should engage the support of local NGOs to promote civic education across Nigeria in culturally appropriate ways. The NGOs should be empowered to define the legal concept of citizenship and summarize specific civil rights enshrined in the Constitution into a Charter of Rights and Responsibilities modeled after the Canadian Charter. The Charter should include value positions essential to an effective democracy, such as the rights of citizens, social justice, accountable governance, and rule of law. It can then be commissioned as a resource for civics education in Nigeria.

This article recognizes that Nigeria is grappling with governance challenges orchestrated by two decades of a failed democratic project. Governing these challenges requires knowledgeable leaders and an equally informed electorate. Like any new experiment, there are concerns about the viability of epistocracy as a political system, particularly in a Nigerian context fraught with ethnoreligious and political challenges. But Nigeria will only have effective governance when the right people are saddled with the responsibility to govern. However, change cannot be spontaneous. The implementation of an epistocratic system of governance within the Nigerian context must be incremental, bearing in mind that Nigeria’s democracy is still evolving.

Obasesam Okoi is Assistant Professor of Justice and Peace Studies at the University of St. Thomas , Minnesota, where he teaches Intro to Justice and Peace Studies, Public Policy Analysis and Advocacy, and Social Policy in a Changing World. His research interests and expertise include governance and peacebuilding, insurgency and counterinsurgency, assessment of post-conflict peacebuilding programs and policies, and peace engineering. He has published in prominent peer-reviewed journals such as World Development, Conflict Resolution Quarterly, African Security, and Peace Review.

MaryAnne Iwara is a Senior Jennings Randolph Fellow in the program on Countering Violent Extremism at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), USA, and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nigeria. Very recently, she was a Policy Leader Fellow at the School of Transnational Governance, European University Institute, Florence, Italy. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Leipzig, Germany.

Image Credit: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (via Creative Commons)

- Civil Society ,

- Regimes & Governance

Recommended Articles

What Can Indonesia Learn from Qatar’s Experience in Mediating Conflicts in the Middle East?

Qatar plays a crucial role in mediating conflicts in the Middle East region. Its engagement in negotiations with diverse stakeholders–including countries like Lebanon, Sudan, and Libya and non-state actors such…

Arriving at a Crossroads: Can Europe Avoid Replaying the Policy Failures of the 2014-16 Migration Crisis?

As irregular migration numbers once again soar to historic levels, Europe’s migration challenges remain a difficult challenge to surmount. After years of infighting and foot-dragging, an agreement on a long-stalled…

NATO: Time to Adopt a Pre-emptive Approach to Cyber Security in New Age Security Architecture

NATO is evolving politically and militarily, as it becomes more technologically sophisticated in the cyberspace realm to meet the multidimensional challenges of the twenty-first century. Specifically, NATO continues…

Failed state? Why Nigeria’s fragile democracy is facing an uncertain future

In the first in a series on Africa’s most populous state, we look at the effects of widening violence, poverty, crime and corruption as elections approach

- My father’s senseless murder must be a wake-up call for Nigeria

A series of overlapping security, political and economic crises has left Nigeria facing its worst instability since the end of the Biafran war in 1970.

With experts warning that large parts of the country are in effect becoming ungovernable, fears that the conflicts in Africa’s most populous state were bleeding over its borders were underlined last week by claims that armed Igbo secessionists in the country’s south-east were now cooperating with militants fighting for an independent state in the anglophone region of neighbouring Cameroon.

The mounting insecurity from banditry in the north-west, jihadist groups such as Boko Haram in the north-east, violent conflict between farmers and pastoralists across large swathes of Nigeria’s “middle belt”, and Igbo secessionists in the south-east calling for an independent Biafra once again, is driving a brain drain of young Nigerians. It has also seen the oil multinational Shell announce that it is planning to pull out of the country because of insecurity , theft and sabotage.

Among recent prominent victims of the lethal violence was Dr Chike Akunyili, a prominent physician in Nigeria’s southern state of Anambra, ambushed as he returned from a lecture to commemorate the life of his wife, Dora, who had been the head of the country’s national food and drug agency.

Who killed the widower and his police guard remains unclear. The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), an Igbo secessionist movement whose militancy has grown increasingly violent and which has vowed to prevent November’s elections for governor in Anambra state, has denied involvement. So too has the security agency, the Department of State Services . Eyewitnesses reported that the attackers, who also killed his driver, were shouting that there would be no elections in Anambra .

What is clear, however, is that Akunyili’s murder is far from an isolated event in Africa’s second-largest economy – a country facing multiple and overlapping challenges that have plunged many areas into violence and lawlessness.

From Boko Haram ’s jihadist insurgency in the north, to the escalating conflict between farmers and pastoralists, a growing piracy crisis in the Gulf of Guinea and the newly emboldened Igbo secessionists, Nigeria – under the presidency of the retired army general Muhammadu Buhari since 2015 – is facing a mounting sense of crisis as elections approach in 2023.

Those security issues are in addition to a series of other problems, including rising levels of poverty , violent crime and corruption amid an increasing sense that the central government, in many places, is struggling to govern.

All of which has prompted dire warnings from some observers about the state of Nigeria’s democracy.

One of the bleakest was the analysis delivered by Robert Rotberg and John Campbell, two prominent US academics – the latter a former ambassador to Nigeria – in an essay for Foreign Policy in May that attracted considerable debate.

“Nigeria has long teetered on the precipice of failure,” they argued. “Unable to keep its citizens safe and secure, Nigeria has become a fully failed state of critical geopolitical concern. Its failure matters because the peace and prosperity of Africa and preventing the spread of disorder and militancy around the globe depend on a stronger Nigeria.”

Even among those who dispute the labelling of Nigeria as a fully failed state accept that insecurity is rising.

Nigeria’s minister of information and culture, Lai Mohammed, accepts that insecurity exists but insists the country is winning the war against its various insurgents.

“I live in Nigeria, I work in Nigeria and I travel all around Nigeria and I can tell you Nigeria is not a failed state,” Mohammed told the BBC.

But if the murder of Chike Akunyili represents anything, it is the dangers facing Nigerians in many parts of the country. This has prompted some to argue that the country’s centralised federal model, a legacy of independence and the long years of military rule, is in need of reform.

While Nnamdi Obasi , who follows Nigeria for the International Crisis Group, would not yet brand Nigeria a failed state, he sees it as a fragile one with the potential for the situation to worsen without radical improvements in governance.

“I’d say the country is deeply challenged on several fronts,” he said from Abuja. “It’s challenged in terms of its economy and people’s livelihoods.

Nigeria since independence

From hopeful beginnings in 1960, west Africa’s powerhouse has suffered civil war, years of coups and military rule, ethnic and regional conflicts, endemic corruption, banditry and Islamist insurgencies. Here are some key events.

New constitution establishes federal system with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a northerner, as prime minister and Benjamin Nnamdi Azikiwe, an Igbo, as governor general, the ceremonial head of state.

Government overthrown in what was seen as an “Igbo coup” and General Aguiyi-Ironsi takes power. Balewa and Ahmadu Bello, northern Hausa-Fulani leader, among those killed

Lt Col Yakubu Gowon becomes head of state. Estimated 30,000 Igbos massacred in riots in northern Nigeria, causing about 1 million to flee to south-east

Between 500,000 and 2 million civilians die from starvation during the war. Gowon attempts reconciliation, declaring “no victor, no vanquished”

Process of moving federal capital to Abuja begins

Succeeded by top aide, Lt Gen Olusegun Obasanjo, who initiates transition from military rule to US-style presidential system

Shehu Shagari, a northerner, becomes first president of second republic, with Igbo vice-president

Coup led by Maj Gen Muhammadu Buhari after disputed elections

Chief Moshood Abiola is apparent winner

In 2000, government declares that Abacha and his family stole $4.3bn from public funds

He is arrested for treason and jailed for four years

The writer and campaigner against oil industry damage to his Ogoni homeland, is executed with eight other dissidents . EU imposes sanctions and Commonwealth suspends Nigeria’s membership

Clashes with Christians opposing the issue lead to hundreds of deaths

Obasanjo elected for second term despite EU observers reporting “serious irregularities”

This leads to attacks to pipelines and other oil facilities and the kidnap foreign oil workers

Subsequently more than 100 are killed in co-ordinated bombings and shootings in Kano

A state of emergency is declared in northern states of Yobe, Borno and Adamawa. Insurgent violence mounts in eight other states

They are taken from a boarding school in northern town of Chibok. Over the next year, Boko Haram launch series of attacks across north-east Nigeria and into neighbouring Chad and Cameroon, seizing several towns near Lake Chad. Group’s allegiance switched from al-Qaida to Islamic State

The intention is to push Boko Haram out of towns and back into their Sambisa forest stronghold. UN refugee agency, UNHCR, says conflict has caused at least 157,000 people to flee into Niger, Cameroon and Chad . A further one million people estimated to be internally displaced inside Nigeria

He is the first opposition candidate to do so in Nigeria

US thinktank Freedom House claims polls “marred by serious irregularities and widespread intimidation ”. At least 141 people killed in communal clashes between Fulani and Adara in Kaduna state

Youth protests against police brutality, focused on the notorious Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) , spread across cities in the south. The #EndSARS movement ends with massacre of still unconfirmed number of protesters shot by security forces at Lekki tollgate in Lagos

They also abduct nine women and girls in Takulashi, Borno state. The following month Boko Haram abduct 334 boys from school in Kankara, Katsina state; days later, 80 pupils of madrasa abducted in Dandume , Katsina State

Isis-linked militia seizes arms from Boko Haram and integrates former commanders and fighters. Analysts say Iswap’s greater discipline and strategy of both co-opting and coercing local communities has helped it expand across Sahel and poses bigger threat.

Nigeria spends 1.47tn naira (£2.6bn) on servicing domestic and external debt in first half of 2021, according to data from Debt Management Office

“There is a sense of disappointment in the fact that the country hasn’t developed as people had expected and has suffered reversals in poverty and youth unemployment. Then there’s the dearth of infrastructure and a generally very poor quality of services.

“On the security front there are several main areas of concern. The first is the north-east, which is where Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa (Iswap) are located.

“In the north-west there are armed groups who are generally referred to as bandits but who have, in a sense, grown beyond that definition of ‘bandit’. [Recently] they attacked a military camp in Sokoto state and killed 12 military personnel.

“Then there is the old problem in the Niger delta [Nigeria’s main oil-producing region], which remains unresolved.”

But the Niger delta’s bubbling disquiet has in recent years been eclipsed by other conflicts – particularly that between pastoral herders and farmers in Nigeria’s central belt, and the re-emergence of an armed Biafran nationalist movement in the Igbo south-east. This separatist activity is happening for the first time since the end of the Biafran war , from 1967 to 1970, which led to widespread starvation and left a million people dead .

For many Nigeria experts, the lesson is not to be found in the individual parts of the crisis but in the way they are beginning to bleed into one another.

As Obasi points out, the conflicts between nomadic herders and farmers have been in part driven by the displacement south of pastoralists from the north-east and north-west by the insecurity in those regions, while a widening sense of impunity across Nigeria has driven people to arm themselves.

“Insecurity seems almost nationwide,” said Obasi. “People have difficulty moving from one city to another, with kidnappings and danger on the highways.

“It is going from a largely governed country with a few ungoverned spaces to a place where there are a few governed spaces while in the rest of the country governance has retreated.”

It bodes ill for Nigeria’s democratic system of civilian government, adopted in 1999 after long years of military rule that began in 1966 apart from a brief four-year interregnum during President Shehu Shagari ’s second Nigerian republic, which ended in 1983.

It was Buhari – who now calls himself a “converted democrat” – who succeeded him as head of state after he overthrew Shagari’s government in a military coup.

While the 2011 elections were seen by the US as being among the “ most credible and transparent elections since the country’s independence ”, Nigeria’s politics have long been complicated by an unwritten agreement among its elites that power should rotate between a figure from the Muslim-dominated north and the mainly Christian south every two terms. With Buhari’s two terms due to end in 2023, power will then – in theory at least – rotate to the south.

Leena Koni Hoffman, a research associate at the Chatham House thinktank and a member of the Nigerian diaspora, says ordinary Nigerians feel “vulnerable” and “grim”, suggesting that the rotational system of government may no longer be fit for purpose.

“The agreement negotiated by the elites is broken. It is not inclusive and the democratic dividend is not being distributed,” she said.

The consequence, she adds, has been that Nigeria’s politics has fractured, with “people exploiting ethnic and religious differences to give people answers that match questions in any part of Nigeria”.

“To give you an idea of the scale of the conflict happening in Nigeria, I could show you a map coloured pink for where violence is happening – it is pink all over.

“For a country that has not been at war since the Biafran war that ended in 1970 – and in the middle of the longest stretch of civilian democracy – to be experiencing this scale of intense violence should be alarming,” she said.

“We knew a long time ago that the country’s rural population had little security, but now we understand they are being exposed to violent non-state actors who have worked out that the security apparatus is hollowed out.

“My family comes from the middle belt. My father is a retired accountant who wants to farm but he can’t be in his home town because it has been decimated by violence. You hear of incidents where 30 people are killed here, a dozen there. Villages attacked .

“More and more communities are seeing that the government is not stepping in with its security forces and are forming their own vigilante groups.”

Aggravating the sense of a state being hollowed out is an under-resourced and overwhelmed judicial system that has left ordinary Nigerians with little expectation of access to justice.

Writing on Facebook after his death , Akunyili’s daughter described their last conversation the day before his killing, with questions that many Nigerians are asking.

“I asked him if he was being careful and he assured me that he was, going on to add that he never went out any more and was sure to be home by six. Convinced, I reminded him to be even more careful and to take care of himself. “We can choose a different path,” she added, referring to ubuntu , a concept of humanity and community based on the idea: “I am because we are.”

“This current [path] leads to more senseless death and pain for one too many,” she said.

- Crisis Nigeria

Most viewed

20 years of democracy: Has Nigeria changed for the better?

Two decades after the West African country’s army handed power to a civilian leader, many question if life has improved.

Two decades ago, in a colourful ceremony held in the capital, Abuja, Nigeria’s military handed over power to an elected civilian leader.

Generals had ruled the oil-rich West African country for the previous 15 years.

Keep reading

Nigeria’s women drivers rally together to navigate male-dominated industry, ‘i blame the government’: poor kenyans say no support amid record flooding, ‘we need you’: solomon islands’ support for us agency’s return revealed, ‘triple spending’: zimbabweans bear cost of changing to new zig currency.

The ceremony was attended by heads of state and representatives from more than 40 countries.

The mood was upbeat and the new leader promised prosperity to the thousands of his countrymen who were in the stadium. Millions of others watched the ceremony on television. Others listened to newly elected president Olusegun Obasanjo’s speech on radio.

But after 20 years of democracy and four presidents, where is Nigeria today?

Economic malaise

The country’s economy has seen a boom since the return of civilian rule. Nigeria’s GDP has grown six-fold since 1999, according to World Bank data.

In 1999, despite its vast oil wealth, Nigeria’s GDP was a mere $59bn. That figure skyrocketed to $375bn by the end of 2017.

“The economy is doing much better now because there is a greater level of trust in our economic institutions. There is also more foreign investments now compared to the military era,” Aliyu Audu, an Abuja-based economist, told Al Jazeera.

Nigeria, the continent’s most populous country, is still heavily reliant on oil. Petroleum represents more than 80 percent of total export revenue, according to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

When the global oil price crashed in 2016, Nigeria’s economy was not spared. The country went into a recession, its first in 25 years.

The economy, the biggest on the continent ahead of South Africa, has not fully recovered. Unemployment stands at 23 percent and inflation at 11 percent, according to official figures.

“Nigeria’s economy needs to diversify. We need to tap into the agricultural sector where the country can put millions of the unemployed to work. Investment in infrastructure will also put many young people to work and reduce double-digit inflation,” Audu said.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics figures, 43 percent of the country’s 190 million population is either unemployed or underemployed.

Despite the recent economic boom, extreme poverty is common. Some 87 million Nigerians live in dire poverty, according to Washington-based Brookings Institution.

Nigeria overtook India, a country of 1.3 billion people, last year as the country that is home to the most extremely impoverished people in the world, it said.

Vast corruption

Nigeria still remains one of the most corrupt nations on the planet. Transparency International ranked the country 144 out 180 in its 2018 corruption perceptions index.

If corruption is not dealt with immediately it could cost Nigeria up to 37 percent of its GDP by 2030, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), a global auditing firm.

This cost equates to nearly $2,000 per Nigerian resident by 2030, PwC said.

President Muhammadu Buhari launched an anti-corruption drive after taking office in May 2015.

“Corruption is still a huge problem, but it is not like what it was before. That is because the people have the choice to get rid of a leader if he is corrupt. That was not possible under the military generals. There are also whistleblowers now,” Audu noted.

Security issues

Since 2009, northeastern Nigeria has been hit by security challenges. Boko Haram, a group that wants to establish an Islamic state following a strict interpretation of Islamic law, has waged a deadly insurgency.

The violence has killed thousands of people and forced more than two million from their homes.

The United Nations and human rights activists accused both Boko Haram and security forces fighting it of putting civilians, including many children, in harm’s way.

The violence has spread to neighbouring Niger, Chad and Cameroon, prompting a regional military coalition against the armed group.

In recent weeks, the coalition forces have pounded Boko Haram hideouts in the Lake Chad area with air strikes as well as launching ground assaults.

Boko Haram fighters kidnapped at least 276 girls from a secondary school in Chibok town. Five years after the attack, more than 112 girls are still missing.

A total of 107 girls have been found or released as part of a deal between the Nigerian government and the armed group.

Boko Haram allegedly operates its largest camp in the vast Sambisa forest in Nigeria’s northeast.

The forest stretches for about 60,000 square kilometres in the southern part of the northeastern state of Borno, which has borne the brunt of Boko Haram’s violence.

“More needs to be done to protect and preserve basic human rights in parts of the northeast. People live in fear from Boko Haram,” Eze Onyekpere, a human rights activist, told Al Jazeera.

“Apart from the areas facing Boko Haram insurgency, rights of citizens have improved significantly since the return of civilian rule. Arbitrary arrests and torture are not common. We also have a constitution that safeguards the rights of all citizens,” Onyekpere added.

Press freedom

Under the military, press freedom was severely restricted. Whistleblowers faced detention and possibly torture in custody.

Twenty years later, Nigeria has a vibrant media with the country also hosting bureaus for some of the world’s major media groups.

Reporters Without Borders ranks Nigeria 120 out of 180 in its 2019 press freedom index.

“Nigeria has come a long way, but it still has a long way to go. We could have been far ahead of where are currently,” Onyekpere said.

- EssayBasics.com

- Pay For Essay

- Write My Essay

- Homework Writing Help

- Essay Editing Service

- Thesis Writing Help

- Write My College Essay

- Do My Essay

- Term Paper Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Write My Research Paper

- Assignment Writing Help

- Essay Writing Help

- Call Now! (USA) Login Order now

- EssayBasics.com Call Now! (USA) Order now

- Writing Guides

How to write Essay About Democracy in Nigeria?

College and university students are often given controversial assignments that are far from easy to accomplish. One of these assignments can be writing a basic essay about democracy in Nigeria. Actually, writing a paper on controversial “bright” topics is not an easy task because there are numerous aspects and facts to explore. At the same time, it is easy to get lost in the information details and focusing on primary facts will help you to accomplish your writing assignment. Otherwise, look for additional help and follow essay basics writing steps that we will gladly offer you to you. We have gathered a team of writers who will write a professional essay for you that will serve you as an example of what your essay should look like in the first place

Table of Contents

Writing an Essay About Democracy in Nigeria

It is a common knowledge if you want to solve a problem, first you should identify it. After analyzing the problem and studying all aspects of it, it is necessary to provide appropriate recommendations and possible solutions to the problem. When you write basic essay about democracy in Nigeria, you should take the same approach. Without identifying a problem, there will be no solutions to look for. The main aim of essay about democracy in Nigeria is to examine problems of democracy establishment in this country since 1960 when Nigeria became an independent country from Britain.

We can write Your Essay for You!

Possible topics to discus in your Essay about Democracy in Nigeria

- The Dilemma.

- Democracy, Government and Freedom.

- Review Democracy in Action.

- Democracy: Virtual Representation.

- The People and the Democracy in Nigeria.

- Democracy Model in Nigeria.

- Democracy and its influence on Economy of Nigeria.

- Getting to know the Democracy in Nigeria.

- The Press and the Democracy in Nigeria.

There is a widespread opinion that the main problem of Nigerian democracy is absence of real charismatic leaders, who can efficiently manage human resources of this country. Mismanagement of the God-given resources in Nigeria resulted in massive unemployment and high level of poverty in the country. Consequently, it led to never-ending tension among people, lack of patriotic feelings and ongoing vandalizing. Political and economic instability influence all the aspects of human well-being in the most negative way.

The essay about democracy in Nigeria aims to find the reasons of democratic problems in the country, providing solutions for already existing problems and preventing prospective threats in the future.

The Reasons of Nigerian Problems with Democracy

- Nigerian people do not want to learn from their own history, leading to the repeating of the same problems year after year.

- Failure of country leaders and their inefficiency in ruling of the country.

- Complexity and heterogeneity of Nigerian population.

- Existence of several hundreds of mutually unintelligible languages, spoken in the country, provoking misunderstanding among people and government in general.

How to improve situation with democracy in Nigeria?

- Leadership is a key factor in the development of Nigerian democracy and society in general.

- Strong leader who will govern the country should be the center of social, economic and political life of Nigeria.

- If one compares democracy in Nigeria with a ship, the country leader is the captain. Captain’s determination, commitment and skills bring success to the voyage. The country leader as a ship’s captain should have commitment to result, self-discipline, strong faith and in the success of all his deeds.

- Nigerian leader should have courage to take risks, to make challenging decisions that will lead to the development and growth of the country’s economy.

What is worth mentioning in your Essay about Democracy?

- One more thing that is obligatory for the development of the country is the belief in democracy. Belief of every society member into success of the country is simply crucial. Even the smallest child should understand that his hands create success of the country. Every person should strive for creation of a better future for his society. Every person should strive for the development of the democracy because democracy supports freedom. Democracy provides equality in high esteem. And these are factors worth to fight for, factors that can be the life goal for people, especially living in Nigeria.

How Can We Help?

If you find yourself struggling with writing a competitive essay about democracy in Nigeria, we believe you can trust your basics writing assignments to our team of professional writers. Having a wide experience in variety of paper writing assignments from students around the globe, we will gladly help you with your assignments as well.

DEMOCRACY UNDER STRAIN: SEEKING SOLUTIONS FOR NIGERIA

Sep 15, 2020 | Press Releases

In Nigeria’s 60 years of self-rule, her democratic journey has been chequered. From the First Republic government which took the reins from the colonial administration to the present Fourth Republic, Nigeria’s attempts at democratic rule have been interrupted by a cumulative 29 years of military interregnum. The country is currently enjoying her longest unbroken spell of democratic rule since 29 May 1999.

As the world marks this year’s International Day of Democracy, with the theme ‘Democracy under Strain: Solutions for a Changing World’, and this year’s celebration coinciding with the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, emphasis should be to support human rights, the rule of law, peace and stability, which are all critical democracy development indicators.

The National Association of Seadogs, Pyrates Confraternity, congratulates Nigerians and the Nigerian government for keeping the fire of Democracy burning in the last twenty-one years of the Fourth Republic. Although the challenges have been enormous, the collective will of Nigerians has proven stronger than the divisive forces which habitually scuttled our democratic sojourn before now.

The citizens are the centrepiece of any democracy. While the people confer legitimacy of power through their votes, the elected government is expected to meet their needs and aspirations. Consequently, obnoxious policies like the recent hikes in Premium Motor Spirit pump price and electricity tariff at the same time, without taking into consideration the prevailing socio-economic realities, and the devastating economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, are clearly insensitive, undemocratic, and unacceptable.

Also, the attempted passage of the vexatious Social Media Bill and the latest attempts at restricting media coverage of the National Assembly are potent threats to the guaranteed freedoms which should naturally be entitlements from our hard-won democracy. The loss of confidence in the integrity of the national electoral process, which is ridden with violence, voter intimidation, ballot rigging and complicity by state actors, heightens concerns about the future of democracy in Nigeria.

According to the Global Terrorism Index 2020, Nigeria currently ranks third in the list of most terrorised countries in the world, just behind Afghanistan and Iraq. In the same week, the 2020 mortality estimates released by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) revealed that Nigeria has overtaken India to become the world’s number one contributor to deaths of children under the age of five; a development that was actualised two years earlier than predicted, according to Thisday Newspaper report of September 10, 2020.

Human security, whether defined as freedom from want (access to a minimum threshold of food, water, healthcare, shelter, education, and work), or freedom from fear (national or territorial security), is an essential entitlement of democratic governance. Therefore, any threat to security in Nigeria, occasioned either by ineffective and harsh economic policies, or the activities of terrorists and other criminal elements, portend great danger to the survival of Nigeria’s democracy.

Against this backdrop, we demand as follows:

- That governments at all levels must strive harder towards strengthening the time-tested components and pillars of democracy namely: security and welfare of the people, rule of law, equality, rights, liberties, and opportunities.

- That political institutions including the Independent National Electoral Commission, political parties, pressure groups, the arms of government, mass media, and civil society groups, need to be strengthened and accorded full independence from interference in the drive towards deepening our democracy.

- That President Muhammadu Buhari should revisit and sign into law the 2019 Electoral Reform Bill presented to him before the 2019 general elections, and equally to ensure a conducive environment for a free press and for civil society organisations to flourish, in the interest of democracy.

- That equality before the law is non-negotiable in a democracy. The recurrent disobedience of court orders granting bail to Nigerians in criminal proceedings initiated by the Federal Government, and such other brazen illegalities deemed injurious to our body polity are major obstacles to the attainment of enduring democracy. Selective justice, preferential or detrimental treatment in the application of the law are an anathema to democracy.

- That the Federal Government of Nigeria must do more than the jaded rhetoric of “bringing the perpetrators to book” and other such ineffectual clichés towards finding a lasting solution to the ethnic and religious tensions in Kaduna, Plateau, Benue and other affected parts of the country.

Nigeria as the largest democracy in Africa should be the torchbearer and pacesetter in the propagation and entrenchment of democracy across the African continent and beyond. This year’s celebration offers the nation another opportunity to reflect on the imperatives towards deepening and elevating democratic governance in Nigeria.

Abiola Owoaje NAS Cap’n Abuja, Nigeria

Share this:

You may also like….

Mubarak Bala: A Call For Justice, Equity and Fairness

May 3, 2024

Since its official proclamation by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1993, sequel to the recommendation...

May Day 2024: A Clarion Call to Nigeria Labour

May 2, 2024

The International Workers Day is marked on May 1 across the world, to celebrate workers and further the continuous...

DIA’s assault on press freedom, threat to democracy

Apr 3, 2024

Mr Segun Olatunji, the editor of FirstNews newspaper, who was abducted by operatives of the Defence Intelligence...

Thoughts and perspectives on democratic practices in Nigeria

Open submission by Eziano Spencer

The ruling party in Nigeria is not doing anything different from the past government. For years we have been yearning for internal democracy, but we are still very far from it. The central government and its 36 states have abandoned their manifestos. Promises are not kept.

There is no strong leadership, and decision taking is so slow - it can take months - so we are having many crises and controversies all over. Party members are taking each other to court, up to Supreme Court level. A current case involves the executive, the senate president and the legislature.

Political parties are not inclusive or participatory enough. Nigerian politics is personality based. People want to exercise authority and dictate what happens in parties. Those who have looted the government treasury become godfather figures, winning elections and claiming power, all to acquire more wealth and protect their investments, arrogating power to themselves.

There is no transparency and accountability in the political system. Politicians do not take care of those who elected them into power and reached out to them or carry them along. Candidates are imposed on voters. Those candidates are not their choice and not the right candidates.

Politicians acquire power to deal with their opponents and to solve their personal problems. They are not there to make history for themselves or make policies that will affect the lives of the people.

At the helm of affairs only one person is saying that he will fight corruption. Every other person around is silent about it, and some of them have been found to be corrupt. Some of those who were in the past administration, who are known to have looted the government treasury when they were governors or held other political positions, have changed to the ruling party and are serving in the present government. Ministers, governors and other political office holders are not talking about or fighting corruption. The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission is not investigating them; it is going after the opposition members, which makes their activities selective. This action has silenced opposition members. Though we know that some huge amounts of money have been recovered from leakages in the system and from corrupt past political office holders, there is silence about those who have defected from opposition party to the ruling party. This is not good for our internal democracy. There is continuing abuse of public funds. Those who have their hands in the public treasury, from local government to state government up to the federal level, run, control and hijack the ruling party. They have become godfathers and kingmakers. They have bought over our traditional rulers. This does not augur well for our democracy.

The Federal Government have refused to recognise the critical problem of the massacre of the Benue people in Benue and Taraba States by terrorist Fulani herdsmen. Over months around 25,000 men, women and children were slaughtered with knives, shot with AK47 rifles or had their houses burnt down and had all their farm produce and farmland destroyed. On one day alone around 71 children, men and women were massacred by the herdsmen. This came without response and intervention from the federal government, which failed to send armed policemen and the military for operations. The state governors have no control over the armed police or the army: they have to wait for orders from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria before they can intervene. In Nigeria it is a serious crime and offence to be seen carrying arms, which should lead to arrest. These cattle herdsmen carried arms about without being arrested by the police. It is generally believed that this was because the president is a Fulani man, which means no one can arrest the Fulani cattle herdsmen.

Just recently at a catholic church, during one of their early morning services, around 20 people were killed, including two reverend fathers. This was followed by a mass protest by catholic church members and their priests in most states, before they buried their members. Professor Wole Soyinka, the Noble laureate, demanded international intervention. The unarmed Benue people and the Governor have for months been crying for help through the media from the United Nations and Africa Union. Thousands of homeless Benue people are internally displaced and in camps looking for help and living in fear. Nigerian people cannot conduct business in Benue or go to a place of worship there.

But politicians are not interested in the killings. We need a new leader to build confidence in Nigerians. The desperation of politicians brings about violence and killings. Feeding on poverty and insecurity, they import small arms into the country, and arm our unemployed youths and students, who are cultist in our higher institutions. They have rigged elections and clamped down on their opponents.

Students and others are recruited by Independent National Electoral Commission for jobs during elections. Their lives are put at risk by the politicians who are desperate. They manipulate them and threaten them with guns to accept rigged election results or face being killed if they refuse to cooperate. This has not helped our democracy.

The only thing the Nigerian government relies upon is oil. Each state is blessed with abundant mineral resources and land for farming. In the past our economy depended on agriculture and the economy was booming. Since the discovery of oil in the south of Nigeria, states have abandoned farming and go to the central government every month to get an allocation from the revenue from oil for their state. If Nigeria is restructured, we will stop depending on oil and develop our economic potential. It is only a few selfish, self-centred people or states that do not want a restructure.

The high levels of poverty in our land have led to the trading of human beings for exploitation for slavery and prostitution. Parents even allow human trafficking agents to take their daughters out of the country to Egypt, Oman and Saudi Arabia, under the guise of becoming housemaids or deceiving them that they are going to become shop workers. These girls, when interrogated, do not know where they are being taken to and what they are going to be used for. This has become a big business between the agents and migration officers at the airport. The agents bring these girls from Kwara State, Ondo State, Osun State, Ekiti State and neighbouring West Africa countries. They travel with Nigerian passports, and some with West African passports. The immigration excuse is that the women are above 18 years and if they were denied from travelling, who would refund their ticket money?

We can rebuild democracy and respond to democratic challenges through the effort of civil society by making sure that the 1999 Constitution is revisited. The desperation, killings, looting of the treasury and the lack of economic development are a result of the huge amounts of salaries attached to political offices, the power of office holders to award billions of Naira in contracts, and the fact that they do not need to declare their assets when they assume office and after their tenure, both at home and abroad. Salaries and allowances should not be attached to political office holders who want to serve the people. The total amount of money to be received monthly by the president should not exceed 400,000 Naira monthly and governors and the Senate President should not receive more than 300,000 Naira monthly. This will help to reduce the desperation for power and the killings that follow and encourage economic development.

Auditors should be recruited and attached to each project and contract awarded, with spending monitored and quarterly reports published.

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission office should not be headed by any government agencies like the police. A separate body, like the accounting body, should head that office for accountability and transparency.

More technical schools should be built to train our young people and help them acquire skills. They should be trained for one year before thinking of looking for jobs. More skills acquisition centres should be built by state governors for new graduates to acquire skills. Young people should be trained in how to demand from their government what they need.

Our leaders and policy makers should guide the utterances they make concerning their citizens; recently this has led to some Nigerian youths who had travelled to Tanzania being deported by Tanzania immigration officers after their president had said that they do not want to work.

Peace education should be taught from the primary school to university level to reduce religious and ethnic killings every time there is a conflict.

- Reimagining Democracy

- #ReimaginingDemocracy

DIGITAL CHANNELS

- @CIVICUSalliance

- Newsletters

- Feedback Form

HEADQUARTERS 25 Owl Street, 6th Floor Johannesburg, South Africa, 2092 Tel: +27 (0)11 833 5959 Fax: +27 (0)11 833 7997

UN HUB: NEW YORK CIVICUS, c/o We Work 450 Lexington Ave New York NY 10017 United States

UN HUB: GENEVA 11 Avenue de la Paix Geneva Switzerland CH-1202 Tel: +41.79.910.34.28

- About CIVICUS

- Youth Action Team

- Member Advisory Group

- Diversity & Inclusion Group for Networking and Action

- Accountability

- Strategic Plan 2022 - 2027

- Civic Space Initiative

- VUKA! Coalition for Civic Action

- Enabling Environment

- Crisis Response Fund

- CIVICUS at the United Nations

- Solidarity Fund

- Affinity Group of National Associations

- CIVICUS Youth

- International Civil Society Week

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Civil Society Resourcing

- Youth Action Lab

- CHARM Africa

- Local Leadership Labs

- CIVICUS Monitor

- Innovation for Change

- Resilient Roots

- Digital Action Lab

- Digital Resiliency Grants

- Work With Us

- Become a Member

- Grassroots Solidarity Revolution

- Stand As My Witness

- CIVICUS In the News

- Media Releases

- CIVICUS Blog

- Annual Reports

- State of Civil Society Reports

- Enabling Environment National Assessment Reports

- More Reports

- Civil Society at the UN

- Action for Sustainable Development

- Toolkits & Guides

- Press Center

How Nigeria has got better at running elections that are freer and fairer

Lecturer, Poliitical Science, Obafemi Awolowo University

Disclosure statement

Damilola Agbalajobi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

The conduct of periodic, competitive, participatory, credible and non-violent elections is one of the main yardsticks used to determine the democratic condition of a state.

As such, Nigeria’s 2019 general election is pivotal to the sustenance and consolidation of the Nigerian democracy. The elections have confirmed the Nigerian electorate’s constitutional right to elect new leaders and punish nonperforming ones by denying them their votes.

Because of the postponement , the Independent National Electoral Commission was under pressure to deliver credible and non-violent elections. Its attempts to distribute materials across Nigeria’s 36 states before election day were marred by mishaps. For example, evidence from European Union observers showed that electoral materials and officers arrived late in some units in the region around Abuja.

Similar cases were reported at some polling units in Kano, Lagos and Kaduna states. Voting in some states was also impacted by a failure of the commission’s card reader machines. In Gezewa and Fagge locations in Kano State, voting began late because the voters couldn’t be identified. Faulty card reader machines also disrupted and delayed voting process in Sokoto, Enugu, and Kogi states.

In addition, elections were cancelled in some polling units in Anambra, River and Lagos states because voting was disrupted by rival political party supporters. Some of the hoodlums who caused the disruption were arrested. Voting resumed and the results are currently being collated.

The outcome of the poll now depends on the electoral commission’s ability to manage the vote counting process in line with the rules governing the conduct of elections in Nigeria.

In my view, Nigeria’s main problem both then and now has been the repeated attempts by candidates to manipulate the process. In this particular election, it must be noted that the incumbent has been defeated in a few areas where he should have won. This is significant. As regards the level of violence, this election has been relatively peaceful when compared to the 2015 poll where 55 deaths were recorded. Even then, there has been a glaring display of ineptitude within security circles, especially in opposition strongholds.

Elections conducted by the commission since Nigeria’s return to democratic governance in 1999 have been marred by electoral malpractices. These include violent attacks on voters, commission officials and members of the opposition.

The majority of these attacks were politically motivated and intended to disrupt the voting process. The elections in 1999, 2003 and 2007 were riddled with irregularities and tainted by violence. But the tide turned in 2011 when a major improvement was witnessed. This was courtesy of new election laws and the 2010 amendment of Nigeria’s constitution which created new guidelines for the conduct of national elections.

Some of the changes that contributed to the success of the 2011 election were the use of biometric data in voter registration and that permanent voters’ cards were issued. These two things sealed the loopholes in the manual voting system which had been particularly easy to manipulate.

The use of National Youth Service officers in the registration of voters and execution of the vote on polling day also contributed to the success of the 2011 poll.

But even with that relative success, post-election violence erupted across 12 states in the west and north east of Nigeria. 800 people died and over 65,000 were displaced.

In a bid to conduct a credible and non-violent election in 2015, the electoral commission postponed the poll because of the security threat posed by Boko Haram. Unfortunately, 58 people still lost their lives to pre-election violence that erupted in 22 states.

Expectations of the 2019 poll

Regardless of the technical and logistics challenges in 2019, there was massive voter turnout . The Nigerian electorate is hungry for a government that will solve their everyday problems. Some of the issues that need fixing are the economy, high cost of living, unemployment, widespread poverty, persistent violent killings, and ethno-religious tensions.

While these are valid concerns, some have speculated that the high turnout could also have been a result of voter bribery . This speculation cannot be dismissed given Nigeria’s history of cash-driven elections .

Additional research was done by Dare Leke Idowu. A Doctoral applicant in the Department of Political Science at the Obafemi Awolowo University in Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

- Peacebuilding

- Democracy in Africa

- Election violence

- Peace & Security

- Nigeria elections 2019

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Challenges and Solutions of Democracy in Nigeria

Introduction, challenges of democracy in nigeria, solutions of democracy challenges in nigeria.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What Can Improve Democracy?

Ideas from people in 24 countries, in their own words, table of contents.

- How politicians can improve

- Calls for systemic reform

- For many respondents, fixing democracy begins with the people

- It's difficult to please everyone

- Economic reform and basic needs

- No changes and no solutions – or at least no democratic ones

- Road map for this research project

- Politicians

- Changing leadership

- Political parties

- Government reform

- Special interests

- Media reform

- Economic reform

- Policies and legislation

- Citizen behavior

- Individual rights and equality

- Electoral reform

- Direct democracy

- Rule of law

- Ensuring safety

- The judicial system

- Codebook development

- Coding responses

- Collapsing codes for analysis

- Characteristics of the responses

- Selection of quotes

- About Pew Research Center’s Spring 2023 Global Attitudes Survey

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Appendix C: Codebook

- Appendix D: Political categorization

- Classifying parties as populist

- Classifying parties as left, right or center

- Acknowledgments

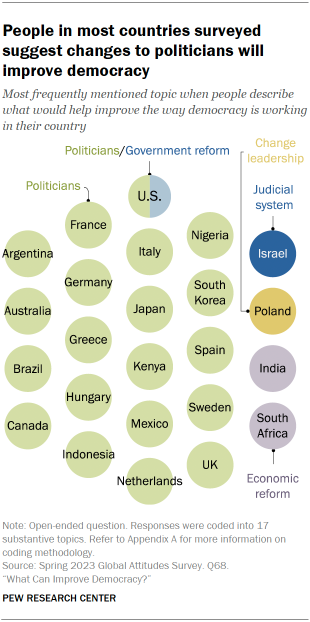

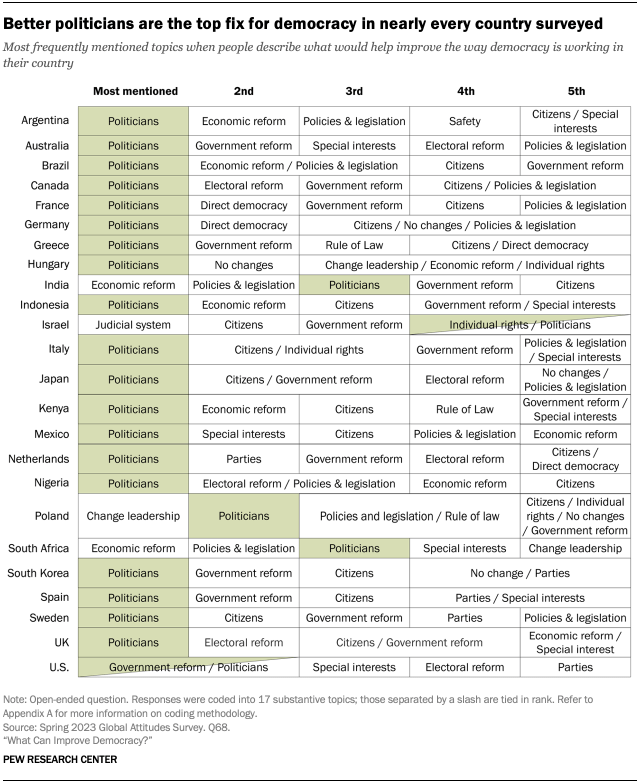

This Pew Research Center analysis on views of how to improve democracy uses data from nationally representative surveys conducted in 24 countries across North America, Europe, the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific region, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. All responses are weighted to be representative of the adult population in each country.

For non-U.S. data, this analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 27,285 adults conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face with adults in Argentina, Brazil, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Poland and South Africa. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel. Read more about international survey methodology .

In the U.S., we surveyed 3,576 adults from March 20 to March 26, 2023. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Researchers examined random samples of English responses, machine-translated non-English responses, and non-English responses translated by a professional translation firm to develop a codebook for the main topics mentioned across the 24 countries. The codebook was iteratively improved via practice coding and calculations of intercoder reliability until a final selection of 17 substantive codes was formally adopted. (For more on the codebook, refer to Appendix C .)

To apply the codebook to the full collection of open-ended responses, a team of Pew Research Center coders and professional translators were trained to code English and non-English responses. Coders in both groups coded random samples and were evaluated for consistency and accuracy. They were asked to independently code responses only after reaching an acceptable threshold for intercoder reliability. (For more on the coding methodology, refer to Appendix A .)

There is some variation in whether and how people responded to our open-ended question. In each country surveyed, some respondents said that they did not understand the question, did not know how to answer or did not want to answer. This share of adults ranged from 4% in Spain to 47% in the U.S.

In some countries, people also tended to mention fewer things that would improve democracy in their country relative to people surveyed elsewhere. For example, across the 24 countries surveyed, a median of 73% mentioned only one topic in our codebook (e.g., politicians). The share in South Korea is much higher, with 92% suggesting only one area of improvement when describing what they think would improve democracy. In comparison, about a quarter or more mention two areas of improvement in France, Spain, Sweden and the U.S.

These differences help explain why the share giving a particular answer in certain publics may appear much lower than others, even if it is the top- ranked suggestion for improving democracy. To give a specific example, 10% of respondents in Poland mention politicians, while 18% do so in South Africa – yet the topic is ranked second in Poland and third in South Africa. Given this discrepancy, researchers have chosen to highlight not only the share of the public that mentions a given topic but also its relative ranking among all topics coded, both in text and in graphics.

Here is the question used for this report , along with coded responses for each country, and the survey methodology .

Open-ended responses highlighted in the text of this report were chosen to represent the key themes researchers identified. They have been edited for clarity and, in some cases, translated into English by a professional firm. Some responses have also been shortened for brevity.

Pew Research Center surveys have long found that people in many countries are dissatisfied with their democracy and want major changes to their political systems – and this year is no exception . But high and growing rates of discontent certainly raise the question: What do people think could fix things?

We set out to answer this by asking more than 30,000 respondents in 24 countries an open-ended question: “What do you think would help improve the way democracy in your country is working?” While the second- and third-most mentioned priorities vary greatly, across most countries surveyed, there is one clear top answer: Democracy can be improved with better or different politicians.

People want politicians who are more responsive to their needs and who are more competent and honest, among other factors. People also focus on questions of descriptive representation – the importance of having politicians with certain characteristics such as a specific race, religion or gender.

Respondents also think citizens can improve their own democracy. Across most of the 24 countries surveyed, issues of public participation and of different behavior from the people themselves are a top-five priority.

Other topics that come up regularly include:

- Economic reform , especially reforms that will enhance job creation.

- Government reform , including implementing term limits, adjusting the balance of power between institutions and other factors.

We explore these topics and the others we coded in the following chapters:

- Politicians, changing leadership and political parties ( Chapter 1 )

- Government reform, special interests and the media ( Chapter 2 )

- Economic and policy changes ( Chapter 3 )

- Citizen behavior and individual rights and equality ( Chapter 4 )

- Electoral reform and direct democracy ( Chapter 5 )

- Rule of law, safety and the judicial system ( Chapter 6 )

You can also read people’s answers in their own words in our interactive data essay and quote sorter: “How People in 24 Countries Think Democracy Can Improve.” Many responses in the quote sorter and throughout this report appear in translation; for selected quotes in their original language, visit this spreadsheet .

The survey was conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023, in 24 countries and 36 different languages. Below, we highlight some key themes, drawn from the open-ended responses and the 17 rigorously coded substantive topics.

In almost every country surveyed, changes to politicians are the most commonly mentioned way to improve democracy. People broadly call for three types of improvements: better representation , increased competence and a higher level of responsiveness . They also call for politicians to be less corrupt or less influenced by special interests.

Representation

“Bringing in more diverse voices, rather than mostly wealthy White men.” Woman, 30, Australia

First, people want to see politicians from different groups in society – though which groups people want represented run the gamut. In Japan, for example, one woman said democracy would improve if there were “more diversity and more women parliamentarians.” In Kenya, having leaders “from all tribes” is seen as a way to make democracy work better. People also call for younger voices and politicians from “poor backgrounds,” among other groups. The opposing views of two American respondents, though, highlight why satisfying everyone is difficult:

“Most politicians in office right now are rich, Christian and old. Their overwhelmingly Christian views lead to laws and decisions that not only limit personal freedoms like abortion and gay marriage, but also discriminate against minority religions and their practices.”

– Man, 23, U.S.

“We need to stop worrying about putting people in positions because of their race, ethnicity or gender. What happened to being put in a position because they are the best person for that position?”

– Man, 64, U.S.

“Our politicians should have an education corresponding to their subject or field.” Woman, 72, Germany

Second, people want higher-caliber politicians. This includes a desire to see more technical expertise and traits such as morality, honesty, a “stronger backbone” or “more common sense.”

Sometimes, people simply want politicians with “no criminal records” – something mentioned explicitly by a South Korean man and echoed by respondents in the United States, India and Israel, among other places.

Responsiveness

“Make democracy promote more of the people’s voice. The people’s voice is the great strength for leadership.” Man, 27, Indonesia

Third, people want their politicians to hear them and respond to their needs and wishes, and for politicians to keep their promises. One man in the United Kingdom said, “If leaders would listen more to the local communities and do their jobs as members of Parliament, that would really help democracy in this country. It seems like once they’re elected, they just play lip service to the role.”

Special interests and corruption

Concerns about special interests and corruption are common in certain countries, including Mexico, the U.S. and Australia. One Mexican woman said, “Politicians should listen more to the Mexican people, not buy people off using money or groceries.” Others complained about politicians “pillaging” the country and enriching themselves by keeping tax money.

For some, the political system itself needs to change in order for democracy to work better. Changing the governmental structure is one of the top five topics coded in most countries surveyed – and it’s tied for the most mentioned issue in the U.S., along with politicians. These reforms include adjusting the balance of power between institutions, implementing term limits, and more.

Some also see the need to reform the electoral system in their country; others want more direct democracy through referenda or public forums. Judicial system reform is a priority for some, especially in Israel. (In Israel, the survey was conducted amid large-scale protests against a proposed law that would limit the power of the Supreme Court, but prior to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and the court’s rejection of the law in January .)

The U.S. stands out as the only country surveyed where reforming the government is the top concern (tied with politicians). Americans mention very specific proposals such as giving the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico statehood, increasing the size of the House of the Representatives to allow one representative per 100,000 people, requiring a supermajority for all spending bills, eliminating the filibuster, and more.

Term limits for elected officials are a particularly popular reform in the U.S. Americans call for them to prevent “career politicians,” as in the case of one woman who said, “I think we need to limit the number of years politicians can serve. No one should be able to serve as a politician for 40+ years like Joe Biden. I don’t have anything against him. I just think that we need limits. We have too many people who have served for too long and have little or nothing to show for it.” Term limits for Supreme Court justices are also top of mind for many Americans when it comes to judicial system reform.

“There are many parts of the UK where it’s obvious who will get elected. My vote doesn’t count where I live because the Conservative Party wins every time. Effectively it means that the majority is not represented by the government. With proportional representation, everybody’s vote would count.” Man, 62, UK

The electoral system is among the top targets for change in some countries. In Canada, Nigeria and the UK, changing how elections work is the second-most mentioned topic of the 17 substantive codes – and it falls in the top five in Australia, Japan, the Netherlands and the U.S.

Suggested changes vary across countries and include switching from first-past-the-post to a proportional voting system, having a fixed date for elections, lowering the voting age, returning to hand-counted paper ballots, voting directly for candidates rather than parties, and more.

Calls for direct democracy are prevalent in several European countries – even ranking second in France and Germany. One French woman said, “There should be more referenda, they should ask the opinion of the people more, and it should be respected.”

In the broadest sense, people want a “direct voting system” or for “people to have the vote, not middlemen elected officials.” More narrowly, they also mention specific topics they would like referenda for, including rejoining the European Union in the UK; “abortion, retirement and euthanasia” in France; “all legislation which harms the justice system” in Israel; asylum policy, nitrogen policy and local affairs in the Netherlands; “when and where the country goes to war” in Australia; “gay marriage, marijuana legalization and bail reform” in the U.S.; “nuclear power, sexuality, NATO and the EU” in Sweden; and who should be prime minister in Japan. (The survey was conducted prior to Sweden joining NATO in March 2024.)

Of the systemic reforms suggested, few bring up changes to the judicial system in most countries. Only in Israel, where the topic ranked first at the time of the survey, does judicial system reform appear in the top 10 coded issues. Israelis approach this issue from vastly different perspectives. For instance, some want to curtail the Supreme Court’s influence over government decisions, while others want to preserve its independence, as in these two examples:

“Finish the legislation that will limit the enormous and generally unreasonable power of the Supreme Court in Israel!”

– Man, 64, Israel

“Do everything to keep the last word of the High Court on any social and moral issue.”

– Man, 31, Israel

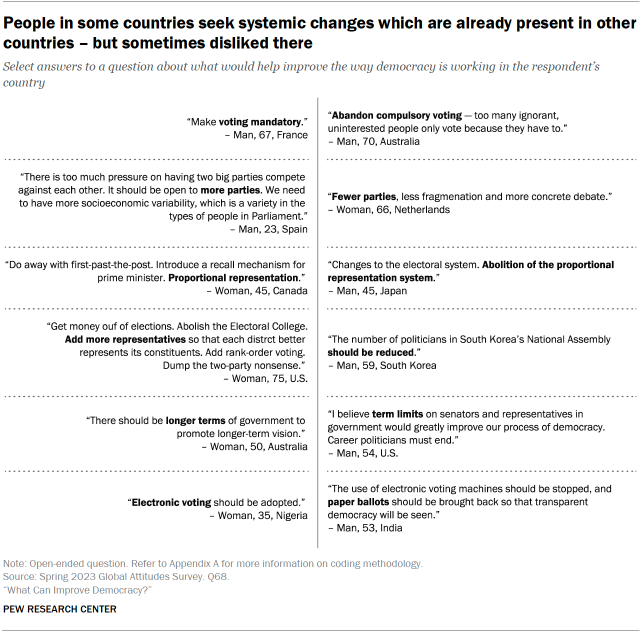

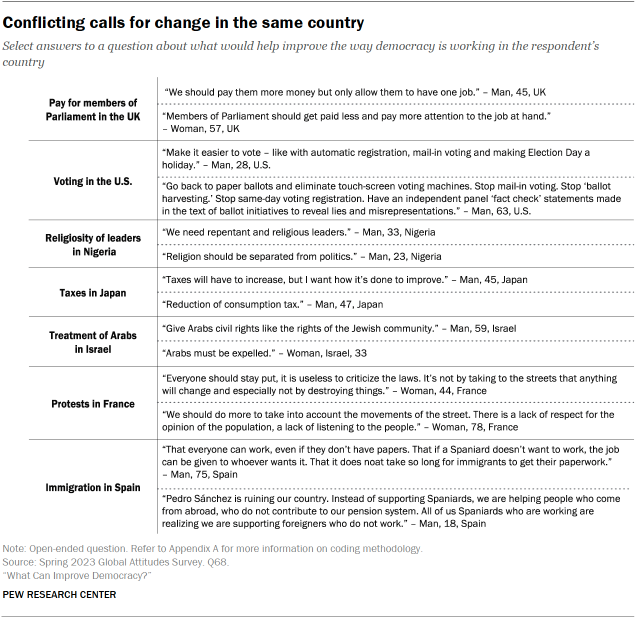

Is the grass always greener?

Notably, some respondents propose the exact reform that those in another country would like to do away with.

For example, while some people in countries without mandatory voting think it could be useful to implement, there are respondents in Australia – where voting is compulsory – who want it to end. People without mandatory voting see it as a way to force everyone to have a say: “We have to get everyone out to vote. Everyone complains. Voting should be mandatory. Everyone has to vote and have a say,” said a Canadian woman. But the flip side one Australian expressed was, “Eliminate compulsory voting. The votes of people who do not care about a result voids the vote of somebody who does.”