TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on May 17, 2021

What is a Short Story? Definitions and Examples

A short story is a form of fiction writing defined by its brevity . A short story usually falls between 3,000 and 7,000 words — the average short story length is around the 5,000 mark. Short stories primarily work to encapsulate a mood, typically covering minimal incidents with a limited cast of characters — in some cases, they might even forgo a plot altogether.

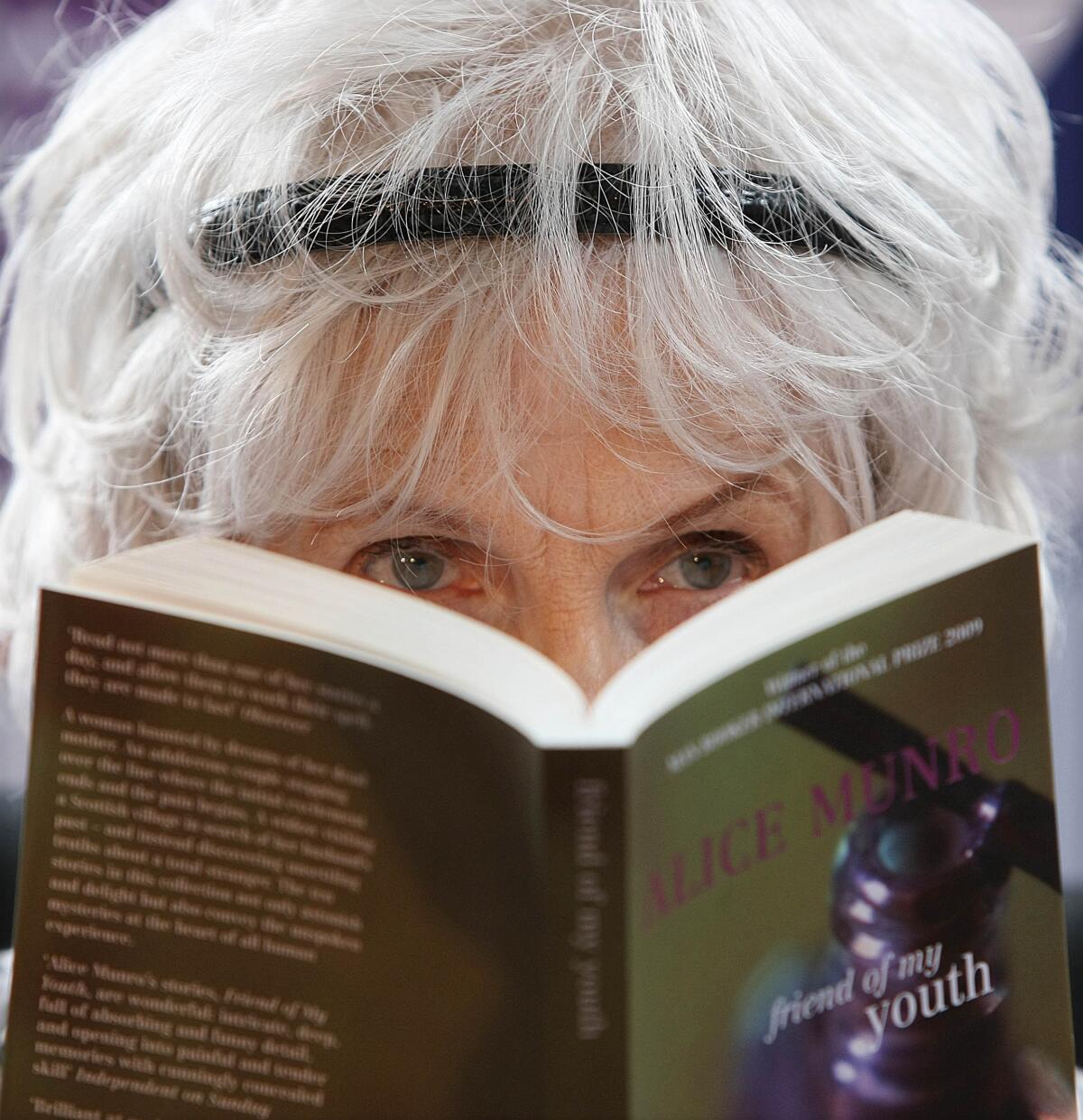

Many early-career novelists have dabbled in the form and had their work featured in literary magazines and anthologies. Others, like Raymond Carver and Alice Munro, have made it their bread and butter. From “starter” short story writers to short story experts, there’s an incredible range of short stories out there.

In this series of guides, we'll be looking into short stories and showing you how any writer can write a powerful piece of short fiction — and even get it published. But before we get into the weeds, let's look at a few examples to demonstrate the range and flexibility of this form.

What short story should you read next?

Find out here! Takes 30 seconds

Broadly speaking, you could answer the question of "what is a short story" in a few ways, starting with the most obvious.

A classic short narrative

Though short stories must inherently be concise pieces of writing, they often incorporate elements of the novel to retain a similar impact. A ‘classic short narrative’ is the most story-telling-by-the-numbers that a short story can get — the plot will imitate long-form fiction by having a defined exposition, escalating rising action , a climax, and a resolution.

Short stories do differ from longer prose works in some respects: they’re unlikely to contain a huge cast of characters, multiple points of view , or successive climaxes like those found in novellas and novels. But despite these cuts, if the author does their job right, a ‘classic’ short story will be just as affecting and memorable as a novel — if not more so.

Example #1: “Speaking in Tongues” by ZZ Packer

Tia, disillusioned with her strict Pentecostal upbringing in a sleepy Southern town, escapes her great-aunt’s clutches to find her mother in Atlanta. This story starts with a classic expository beat — Tia at school, flicking through a religious textbook, dreaming of another life. This is followed by a crisis: Tia travels by bus to the big city, befriends a man on the street, and goes to stay with him, only to learn that he is a drug dealer and a pimp. Eventually, Tia returns home to her great-aunt. In all, it’s a sensitive story about the vulnerability of youth and the longing for family.

As short stories go, “Speaking In Tongues” has a pretty impressive narrative. You can see how the premise and plot could work as a longer piece of fiction, but they pack even more of a punch in this shorter form.

A vignette is a short story that presents a neatly packaged moment in time, usually in quite a technically accomplished fashion. ‘Vignette’ is French word more frequently used to signify a small portrait, but in a literary sense, it means “a brief evocative description, account, or episode”. This could be of a person, event or place.

Fleetingness is at the crux of a vignette short story. For that reason, it is likely to be heavy on description, light on plot. You might find a particularly embellished description of a character or setting, often with a strong dose of symbolism that corresponds with a central theme.

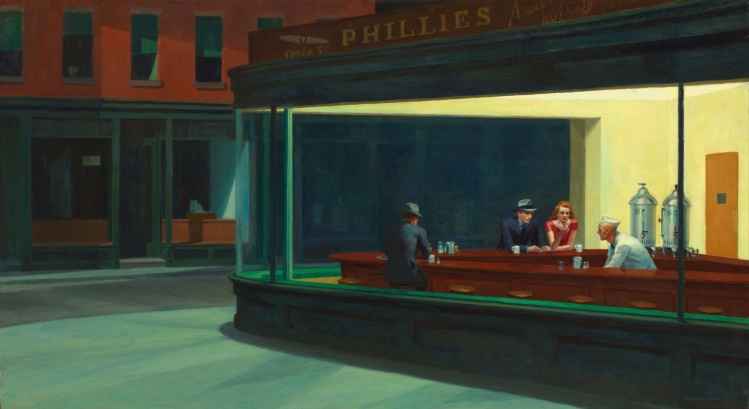

Example #2: “Viewfinder” by Raymond Carver

“Viewfinder” has a simple premise: a traveling photographer takes a photo of the narrator’s house, sells it to him on his doorstep, and is invited in for coffee. The story emphasizes feelings of loneliness that come to the fore in their interaction, captured brilliantly by Carver’s unadorned writing style. Tales like this that attribute importance to the mundane are arguably best served by a concise form as Carver's fascination with banal events could have become repetitive and rudderless in a longer piece of work.

Many critics agree that no one writes the American working classes quite like Carver. His stories chronicle the everyday experiences of Midwestern men and women eking out a living then fish, play cards, and shoot the breeze as life passes them by. It won Carver immense critical acclaim in his lifetime and is a great example of short-form writing that emphasizes mood rather than plot.

An anecdote

An anecdote recounted to friends is most successful when it’s pacey, humorous, and has a quick crescendo. The same can be said of short stories that capitalize on this storytelling device.

Anecdotal stories take on a more conversational tone and are more meandering in style, in contrast to the directness of other short stories and flash fiction . It can have a conventional story structure, like the classic short narrative, or it may focus on a particular stylistic recounting of an event. Basically, an anecdote allows a writer to have fun with the way a story is told — though exactly how it unfolds remains important too.

Example #3: “We Love You Crispina” by Jenny Zhang

Zhang’s 2017 short story collection Sour Heart chronicles the rough-and-tumble lives of recently immigrated Chinese-American living in downtown Manhattan. The stories in this collection are told from the perspectives of children, and the narrative takes full advantage of the impish, filterless way in which children relate their own experiences to themselves and others.

In “We Love You Crispina”, young Christina’s life in a crowded Washington Heights tenement block is refracted through her naive, contradictory understandings of the world. Her parents are struggling to get a leg up and are contemplating sending her back to Shanghai — but Christina is more concerned with how the bed bugs in their cramped apartment are making her itchy, and dissecting the interactions she has in the school playground. It’s a wonderfully nuanced exercise in contrast, as well as a reminder of what feels most important to us when we’re small, rendered potently through Christina’s 'anecdotal' voice.

An experiment with genre

Short stories, by nature, are more flexible pieces of fiction that aren’t wedded to the diktat of longer-form fiction. It means they can play around with and challenge the expectations of a genre’s expected conventions, in a relatively ‘low stakes’ way compared to a full-blown novel.

Oftentimes, an experiment won’t be a complete reinvention of the genre. Instead, one might find a refreshing twist on a classic trope — or, as in the example below, upping the ante and taking a genre to heights it has never been before.

Example #4: “A Good Man is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor

This short story sent shock waves through the American literary establishment when it was first published in 1953. It follows a Southern family on a road trip to visit the children’s grandmother — who end up crashing their car and happening upon a mysterious group of men. I won’t spoil the rest for you, but one word of warning: don’t expect a happy ending.

“A Good Man Is Hard To Find” incorporates common themes of Southern gothic literature , like religious imagery, and — surprise surprise — characters meeting a gruesome demise, but its controversial final scene marks it out. The macabre detail was shocking to audiences at the time but is now held up as a stellar example of the genre (and also exemplifies how a well-executed bit of subversion can become the golden standard in literature!). You might want to sleep with one eye open after reading this, but that’s half the point, right?

An exercise in extreme brevity

How many words do you actually need to tell a great story? If you were to ask that to someone who writes flash fiction , they tell you "fewer than 1,000 words."

The defining element that sets flash fiction apart from the standard-issue short story — other than word count — is that much more needs to be implied, rather than said upfront. Flash fiction, and especially mega-short microfiction, perfectly embody this principle of inference, which itself derives from Ernest Hemingway ’s Iceberg Theory of story development.

Example #5 “Curriculum” by Sejal Shah

“ Curriculum ”, clocking in at exactly 500 words, is a great sampling of the emotional, personal language that appears frequently in flash fiction. A handkerchief, some cream cloth, and a pair of glasses become important symbols around which Shah contemplates identity and womanhood, in the form of a series of questions that follow her descriptions of the objects.

This kind of deliberate, highly considered structure ensures that Shah’s flash fiction makes a razor-sharp point, whilst also allowing for a contemplative tone that transcends the words on the page. When done well, this style of short fiction can be a greater-than-expected vehicle for thoughtful comments on a range of issues.

If you’re in the mood to read more around the form, check out our picks for the 31 best short stories .

As you can see, the short story is an art form on its own that requires deftness, clarity, and a strong grasp of how to make an economy of words compelling and innovative. If you’re feeling ready to write a short story of your own, proceed to the next post in this series.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We have an app for that

Build a writing routine with our free writing app.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling . With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

How to Write a Short Story: Contents

The Core Elements of a Short Story

How to write a short story outline, how to write a short story step by step, how to write a short story: length and setting, how to write a short story: point of view, how to write a short story: protagonist, antagonist, motivation, how to write a short story: characters, how to write a short story: prose, how to write a short story: story structure, how to write a short story: capturing reader interest, where to read and submit short stories.

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid , the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction , such as a setting , plot , and point of view . It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction .

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step-by-step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction , pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator , or pull prompts from this Twitter .

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado . We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

Read more about writing effective conflict here:

What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise .

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

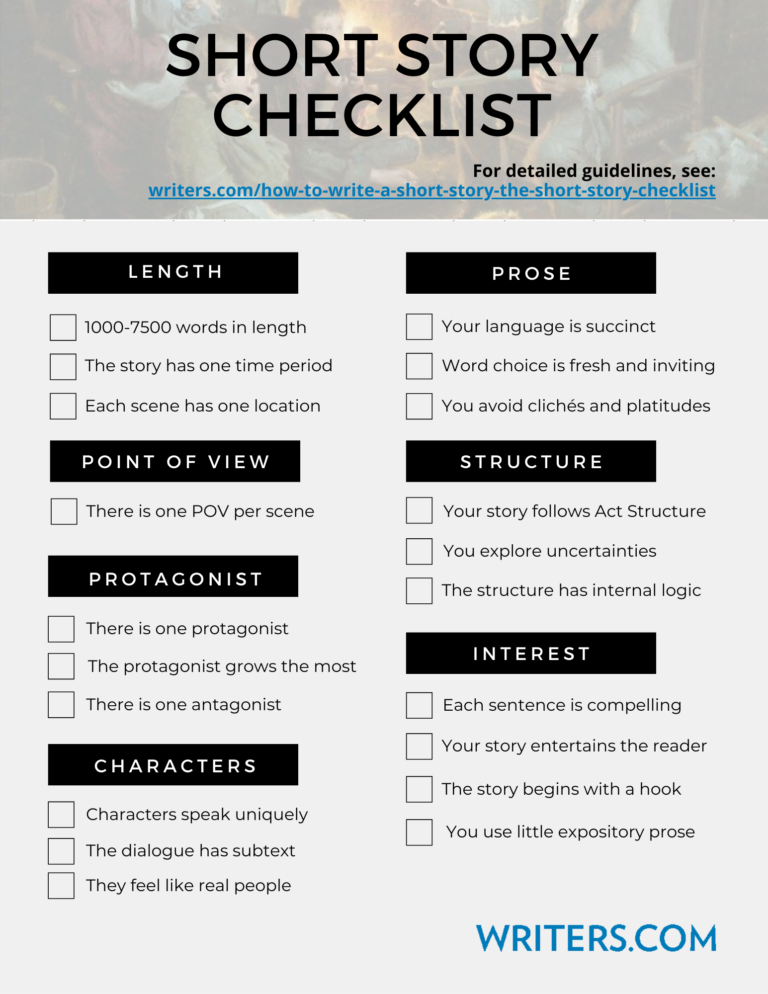

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko . Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download . Enjoy!

Click to download

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident , which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.

Your language is succinct, fresh and exciting, specific, colorful, avoiding clichés and platitudes. Sentence structures vary. In Genre stories, the language is simple, the symbolism is direct, and words are well-known, and sentences are relatively short. In Literary stories , you are freer to use more sophisticated ideas, words, sentence structures, styles , and underlying metaphors and implied motifs.

Your plot elements occur in the proper places according to classical Three Act Structure (or Freytag’s Pyramid ) so the reader feels he has vicariously gone through a harrowing trial with the protagonist and won, raising his sense of hope and possibility. Literary short stories may be more subtle, with lower stakes, experimenting beyond classical structures like the Hero’s Journey. They can be more like vignettes sometimes, or even slice-of-life, though these types are hard to place in publications.

In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape. In Literary short stories, you are free to explore uncertainty, ambiguity, and inchoate, realistic endings that suggest multiple interpretations, and unresolved issues.

Some Literary stories may be nonrealistic, such as with Surrealism, Absurdism, New Wave Fabulism, Weird and Magical Realism . If this is what you write, they still need their own internal logic and they should not be bewildering as to the what the reader is meant to experience, whether it’s a nuanced, unnameable mood or a trip into the subconscious.

Literary stories may also go beyond any label other than Experimental. For example, a story could be a list of To Do items on a paper held by a magnet to a refrigerator for the housemate to read. The person writing the list may grow more passive-aggressive and manipulative as the list grows, and we learn about the relationship between the housemates through the implied threats and cajoling.

Your short story is suspenseful, meaning readers hope the protagonist will achieve his best goal, his Need, by the Climax battle against the antagonist.

Your story entertains. This is especially necessary for Genre short stories.

The story captivates readers at the very beginning with a Hook, which can be a puzzling mystery to solve, an amazing character’s or narrator’s Voice, an astounding location, humor, a startling image, or a world the reader wants to become immersed in.

Expository prose (telling, like an essay) takes up very, very little space in your short story, and it does not appear near the beginning. The story is in Narrative format instead, in which one action follows the next. You’ve removed every unnecessary instance of Expository prose and replaced it with showing Narrative. Distancing words like “used to,” “he would often,” “over the years, he,” “each morning, he” indicate that you are reporting on a lengthy time period, summing it up, rather than sticking to Narrative format, in which immediacy makes the story engaging.

You’ve earned the right to include Expository Backstory by making the reader yearn for knowing what happened in the past to solve a mystery. This can’t possibly happen at the beginning, obviously. Expository Backstory does not take place in the first pages of your story.

Your reader cares what happens and there are high stakes (especially important in Genre stories). Your reader worries until the end, when the protagonist survives, succeeds in his quest to help the community, gets the girl, solves or prevents the crime, achieves new scientific developments, takes over rule of his realm, etc.

Every sentence is compelling enough to urge the reader to read the next one—because he really, really wants to—instead of doing something else he could be doing. Your story is not going to be assigned to people to analyze in school like the ones you studied, so you have found a way from the beginning to intrigue strangers to want to spend their time with your words.

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or want to publish your own stories, you’ll find great literary journals for writers of all backgrounds at this article:

https://writers.com/short-story-submissions

Learn How to Write a Short Story at Writers.com

The short story takes an hour to learn and a lifetime to master. Learn how to write a short story with Writers.com. Our upcoming fiction courses will give you the ropes to tell authentic, original short stories that captivate and entrance your readers.

Rosemary – Is there any chance you could add a little something to your checklist? I’d love to know the best places to submit our short stories for publication. Thanks so much.

Hi, Kim Hanson,

Some good places to find publications specific to your story are NewPages, Poets and Writers, Duotrope, and The Submission Grinder.

“ In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape.”

Not just no but NO.

See for example the work of MacArthur Fellow Kelly Link.

[…] How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist […]

Thank you for these directions and tips. It’s very encouraging to someone like me, just NOW taking up writing.

[…] Writers.com. A great intro to writing. https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-short-story […]

Hello: I started to write seriously in the late 70’s. I loved to write in High School in the early 60’s but life got in the way. Around the 00’s many of the obstacles disappeared. Since then I have been writing more, and some of my work was vanilla transgender stories. Here in 2024 transgender stories have become tiresome because I really don’t have much in common with that mind set.

The glare of an editor that could potentially pay me is quite daunting, so I would like to start out unpaid to see where that goes. I am not sure if a writer’s agent would be a good fit for me. My work life was in the Trades, not as some sort of Academic. That alone causes timidity, but I did read about a fiction writer who had been a house painter.

This is my first effort to publish since the late 70’s. My pseudonym would perhaps include Ahabidah.

Gwen Boucher.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home » Writing » What is a short story?

What is the history of the short story?

Short-form storytelling can be traced back to ancient legends, mythology, folklore, and fables found in communities all over the world. Some of these stories existed in written form, but many were passed down through oral traditions. By the 14 th century, the most well-known stories included One Thousand and One Nights (Middle Eastern folk tales by multiple authors, later known as Arabian Nights ) and Canterbury Tales (by Geoffrey Chaucer).

It wasn’t until the early 19th century that short story collections by individual authors appeared more regularly in print. First, it was the publication of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, then Edgar Allen Poe’s Gothic fiction, and eventually, stories by Anton Chekhov, who is often credited as a founder of the modern short story.

The popularity of short stories grew along with the surge of print magazines and journals. Newspaper and magazine editors began publishing stories as entertainment, creating a demand for short, plot-driven narratives with mass appeal. By the early 1900s, The Atlantic Monthly , The New Yorker , and Harper’s Magazine were paying good money for short stories that showed more literary techniques. That golden era of publishing gave rise to the short story as we know it today.

What are the different types of short stories?

Short stories come in all kinds of categories: action, adventure, biography, comedy, crime, detective, drama, dystopia, fable, fantasy, history, horror, mystery, philosophy, politics, romance, satire, science fiction, supernatural, thriller, tragedy, and Western. Here are some popular types of short stories, literary styles, and authors associated with them:

- Fable: A tale that provides a moral lesson, often using animals, mythical creatures, forces of nature, or inanimate objects to come to life (Brothers Grimm, Aesop)

- Flash fiction : A story between 5 to 2,000 words that lacks traditional plot structure or character development and is often characterized by a surprise or twist of fate (Lydia Davis)

- Mini saga: A type of micro-fiction using exactly 50 words (!) to tell a story

- Vignette: A descriptive scene or defining moment that does not contain a complete plot or narrative but reveals an important detail about a character or idea (Sandra Cisneros)

- Modernism: Experimenting with narrative form, style, and chronology (inner monologues, stream of consciousness) to capture the experience of an individual (James Joyce, Virginia Woolf)

- Postmodernism: Using fragmentation, paradox, or unreliable narrators to explore the relationship between the author, reader, and text (Donald Barthelme, Jorge Luis Borges)

- Magical realism: Combining realistic narrative or setting with elements of surrealism, dreams, or fantasy (Gabriel García Márquez)

- Minimalism: Writing characterized by brevity, straightforward language, and a lack of plot resolutions (Raymond Carver, Amy Hempel)

What are some famous short stories?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843) – Edgar Allen Poe

- “The Necklace” (1884) – Guy de Maupassant

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892) – Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- “The Story of an Hour” (1894) – Kate Chopin

- “Gift of the Magi” (1905) – O. Henry

- “The Dead,” “The Dubliners” (1914) – James Joyce

- “The Garden Party” (1920) – Katherine Mansfield

- “Hills Like White Elephants” (1927), “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” (1936) – Ernest Hemingway

- “The Lottery” (1948) – Shirley Jackson

- “Lamb to the Slaughter” (1953) – Roald Dahl

- “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” (1955) – Gabriel García Márquez

- “Sonny’s Blues” (1957) – James Baldwin

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” (1953), “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (1961) – Flannery O’Connor

What are some popular short story collections?

- The Things They Carried – Tim O’Brien

- Labyrinths – Jorge Luis Borges

- Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman – Haruki Murakami

- Nine Stories – J.D. Salinger

- What We Talk About When We Talk About Love – Raymond Carver

- The Stories of John Cheever – John Cheever

- Welcome to the Monkey House – Kurt Vonnegut

- Complete Stories – Dorothy Parker

- Interpreter of Maladies – Jhumpa Lahiri

- Suddenly a Knock at the Door – Etgar Keret

Do you have a short story collection or another book project in the works? Download our free layout software , BookWright, today and start envisioning the pages of your next book!

This is a unique website which will require a more modern browser to work! Please upgrade today!

This is a modern website which will require Javascript to work.

Please turn it on!

Find what you need to study

Short Fiction Overview

18 min read • november 18, 2021

Laura Walton

Attend a live cram event

Review all units live with expert teachers & students

What is a Short Story?

It’s not just a story that is short. Well, it is that, but a short story is not just a piece of a longer story or novel: it is a brief, stand-alone piece of literature with a beginning, middle, and end, character development, theme, and all of the fun literary devices that exist in longer stories. It does what a novel does, in fewer pages and tighter images, sentences, and phrases. This means that a literary short story is almost always denser than a novel.

Wait. Literary short story ? As opposed to what?

Literary vs. Commercial Fiction

Okay, so. If you like to read, and you read widely, then you probably have a few different types of literature that you go to at different times. Sometimes, you’re lying on the beach, or on a holiday break at home, and you want something easy to follow, with a clear beginning, middle, and end, without complicated plot or character development. That’s cool, and books and stories that fall into that category are called commercial fiction .

Commercial fiction is meant to be consumed quickly and easily, and doesn’t require repeat reading to get the full impact of the stories told. Examples of some popular commercial fiction include novels like Divergent, The Da Vinci Code, Crazy Rich Asians, and The Hunger Games .

There is nothing wrong with reading commercial fiction: even we literature teachers need a break from diving deeply into novels, and these books and stories provide an escape from reality for a short while. But you won’t see commercial fiction appearing on the AP Lit exam. Why? Because there isn’t enough deep analysis to be done with commercial fiction.

As opposed to commercial fiction, which provides an escape from the real world, literary fiction forces us to dive more deeply into the real world, even through fictional worlds, and think about our reality through literary devices and parallels. Literary fiction requires multiple readings, and deep readings at that, to fully understand the text. We are often unsatisfied with the endings of literary short stories and novels because, like in reality, they don’t end with loose ends tied up.

Literary fiction leaves us with questions. It makes us go back and find “something that we missed.” Literary fiction uses figurative language and literary devices - devices that, by definition, are indirect descriptors - to depict a story, and depict an author’s view of the world. The literature you read in your AP Lit class - the kind that can make your head hurt with multiple deeper meanings and symbols - is literary fiction .

Is there a clear-cut line between the two types? Nope. As with most things in life, fiction falls in a spectrum: some commercial fiction has literary elements, and some literary fiction may toe the line of being consumable and commercial (and enjoyable to read!). Just know that what you will study in AP Lit and analyze on the exam will fall into the literary category in some way.

How are short stories used on the AP Literature Exam?

You will read and analyze entire poems during the multiple-choice and free-response Q1 sections of the exam. You will analyze an entire novel or play for your free-response Q3. But short stories don’t have their own special section, and you will rarely, if ever, get to analyze a full short story on the exam.

Then what’s the point of studying short stories??

Firstly, they do appear on the exam, but in excerpts and pieces in the multiple-choice and free-response Q2 portions. (Just because a short story is “short,” doesn’t mean it can fit on one page for your analysis.)

Secondly, analyzing short stories prepares you for reading and analyzing longer novels like a boss scholar: if you’re used to searching a short text for deeper symbolism, characterization , tone , and literary devices , then you’ll use the same skills to search novels and plays.

And finally, because you only get those brief excerpts from short stories, novels, and plays on the exam, and you’re in the habit of reading short stories like a scholar, then you’ll breeze through analyzing the excerpts on the exam. Or it’ll at least make it a bit easier on you.

How to read a short story. Like, really read it.

Okay, cool. Now you know the difference between literary and commercial fiction, why literary fiction is used in your AP Lit class and on the exam, and how literary short stories are used on the AP Lit exam itself. Now, it’s time for why you’re really here.

How the devil do I read a short story like a scholar?

First of all, read the story more than once. Think you’ve got an easy night because your teacher only assigned a ten-page story to read? Think again. Short literary fiction is designed to be perplexing, and reading the story only once is likely going to leave you mega-confused.

Read the story at least twice, ideally three or four times, and annotate the story during those second and third and fourth reads. I always suggest reading it the first time for understanding, and the second and subsequent reads for further comprehension and analysis.

Neat. Got it. But annotation : my teacher tells me to annotate, but I never know what to annotate, or how!

Different people annotate in different ways, and the more you do it, the better you’ll get at annotating in a way that makes sense to you. Start with a simple, consistent symbol system, like this one

! anything that stands out to you in some way, or is surprising

* anything that is important (I’ll get to what can be “important” later on)

? anything that is confusing, or that you have a specific question about

→ anything that has a real-world connection or parallel

Circle words or phrases that are unfamiliar, or that are used in a way that you’ve never seen.

Underline or highlight the particular phrases or passages that elicit these reactions, and mark them with these symbols. A word of caution: avoid highlighting or underlining hugely long passages, and especially without using an annotation system. Otherwise, you might end up with the whole short story highlighted, with no real annotation or notes for you to refer back to!

Next, you want to make notes in the margins near these marked phrases and passages. For example, if something stood out to you, briefly note what about the passage, precisely, stood out. Or, write the question that you have about the particular phrase or paragraph or character. Annotations do not have to be long: they just need to make sense to you as you go back through the text and look for evidence to use in your writing and discussions.

Another effective annotation tool, especially for comprehension, is summary and paraphrasing: next to each passage or paragraph, write a brief summary, in your own words, describing what is happening. In this way, you can also ask questions, mark what stands out to you, and make connections between the text and the real world (which is where you’re going to find themes ). If you want even more practice or guidance with annotation , we have a stream for that !

🎥 Watch: AP Literature - Annotating for Understanding

Now, then. Back to my favorite teacher phrase: “Mark anything that’s important.” You’re probably thinking to yourself, “But everything is important! Highlight all the things!” Or, perhaps, “Nothing is important or more important in this text. Gahhhh!”

So, let’s talk about what's “important” in a short story , shall we? We’ll work with “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin for these sections, so read it and annotate it as explained above. The story is super short, and great for a quick dive into reading short stories like a champ.

The (Sometimes) Hidden Question: Overall Meaning

For every single analysis you do for a short story , you must determine its overall meaning and general themes . Why? Because every AP Lit exam question, whether it directly states it or not, will ask you how some aspect of the story you’re working with ties into the overall meaning of the text .

This phrase is most commonly seen with Q3 prompts (that is, prompts that ask you to analyze full novels and plays), but short stories also have overall meaning and purpose that you need to determine for analysis. Let’s look at some sample prompts to show this.

Sample Prompt 1: In serious literature, no scene of violence exists for its own sake. Choose a novel or play that confronts the reader or audience with a scene or scenes of violence and analyze the significance of the scene or scenes to the work’s meaning. (from CollegeBoard.org)

Sample Prompt 2: Choose a novel or play in which cultural, physical, or geographical surroundings shape psychological or moral traits in a character. Then write a well-organized essay in which you analyze how surroundings affect this character and illuminate the meaning of the work as a whole . (from CollegeBoard.org)

In these two Q3 prompts, as with most of the past and future prompts you’ll see, the question asks you not only to analyze a particular aspect of the story (violence, surroundings, etc.), but how that aspect “illuminates” or highlights the meaning of the work. “Meaning” can also be worded as “author’s purpose,” as in the following sample:

Sample Prompt 3: Although literary critics have tended to praise the unique in literary characterization , many authors have employed the stereotyped character successfully. Select a novel or play and analyze how the conventional or stereotyped character(s) function(s) to achieve the author’s purpose. (from CollegeBoard.org)

When you determine the overall meaning of a text, you’re determining why the author chose to write the text, AKA the author’s purpose, as well. So, don’t fall into the trap where you simply describe the first part of the prompt and leave out tying it back to the meaning; otherwise, you’ve only answered half of the question. Your thesis statement should answer all the questions asked in the prompt.

Short Stories and Complex Relationships. (No, Not That Kind. Maybe.)

Another common phrase you’ll see in AP Lit prompts, especially for Q2 (the prose prompt), is “analyze the complex relationship between…” or other variations of complexity. Because you’re studying and analyzing literary fiction , you will find complexity in the text. Finding the overall meaning or author’s purpose in a text should lead you to the complex aspect of the story you need.

But what, exactly, counts as “complex” or a “complex relationship”? Complexity is anything that makes something, well, complicated. Consider the following example regarding fatherhood:

Society values fathers as figures of protection, love, and wisdom for their children.

How might an author make this idea of the fatherhood complex? They might portray a father who does not display one or any of these traits, or a character who questions what fatherhood means to him versus what his society believes.

Or, to tie an example into “The Story of an Hour”:

Society dictates that marriage is an expression of love and devotion, and a spouse should grieve the loss of a spouse.

How does the author create complexity in her short story ? Louise, rather than feeling grief and loss at her husband’s death, feels freed and triumphant, even though she knows this is wrong in her society’s eyes.

Your prompt may (and has in the very recent past!) ask you to describe “how the author explores the complex interplay between emotions and social propriety” in the passage. You would then use examples of the plot, diction, literary devices , and figurative language to describe how and why the author shows this complexity.

Literary Devices and Figurative Language in Short Stories

One of the major items you’ll look for in short stories on the AP Lit exam is literary devices, and their effect on the passage as a whole , or tied into a particularly complex aspect of the story. So, you’ll want to mark the literary devices you see, and describe the what, how, and why of the device:

- What is the literary device being used?

- How does the author use this device? Who or what does it describe? Where does it appear? How does this device show complexity and overall meaning ?

- Why does the author choose to use this device to accomplish what? Why does the author choose this literary device over another to show complexity and meaning?

A common pitfall with describing literary devices is doing just that - simply describing the device, and not what its purpose or effect is in the story. Any phrase or sentence you pull should be evidence towards your thesis and used as such in your essay. If you highlight a literary device from a story in your essay, you’d better be ready to describe how and why it’s used; otherwise, you’ve wasted valuable time and cramped your hand for nothing.

🎥 Watch: AP Literature - Figurative Language and Function

Let’s do an example from “Story of an Hour”:

There was a feverish triumph in her eyes, and she carried herself unwittingly like a goddess of Victory.

There are multiple literary devices we can pull out of this sentence, but let’s focus on the simile: “she carried herself unwittingly like a goddess of Victory.” Great! We have the what : Chopin uses a simile to describe what Louise looks like. But don’t stop there.

How does Chopin use this device? She uses the simile to compare her main character, Louise, to a goddess of victory, of triumph, as she leaves her room for the first time since believing she is free from the shackles of marriage.

Now, for the more difficult part: why does Chopin use a simile, and in particular, this simile, to describe Louise? You may consider why she would choose a simile over other literary devices (such as imagery or metaphor), or why she chose the particular image of a goddess of victory instead of simply a goddess, or a winner of a race, or something similar.

This is where your analysis ties into your thesis. What are you trying to prove through your thesis, and how does this simile, and use of this simile, support your argument? How does this phrase you’ve pulled tie into the complexity and meaning of the story overall?

The simile can hearken back to the discussion of social complexity: that Louise, rather than follow social customs and grieve her husband’s death, walks like a goddess of victory over the stifling institution of marriage. But, she is just that: like a goddess of victory, rather than metaphorically being one, and will lose that image at her husband’s arrival.

Characterization in Short Stories

Remember: a short story is not just a piece of a story. It’s a story with a plot and character development, with a defined beginning, middle, and end, in a shorter space than a novel or play. Sure, you might be thrown into the middle of a setting or scene, but that doesn’t mean that a character isn’t fully hashed out in a short span of time, or that a “complex relationship” can’t develop between two or more characters.

This means that you, yes you, can and will do complex analyses of characters in short stories or excerpts.

When reading literary short stories, look for and annotate any figurative language , diction, and narration that fleshes out a character. Physical descriptions, flashbacks, dialogue, and the characters' responses to the action of the story all form their characterization . If an author bothered to fit a description into the small space they chose to write the story, then it’s important and should be marked.

In “The Story of an Hour,” Louise is a full-fledged character with personality traits, flaws, and development, all in the span of two pages. Chopin describes the “complex relationship” between Louise and her husband in two short sentences:

“And yet she had loved him--sometimes. Often she had not.”

Spouses are expected to love each other, yet in these lines, Louise admits that this was not always the case. Chopin also portrays Louise’s complex relationship with her society in the following paragraph:

“There would be no one to live for during those coming years; she would live for herself. There would be no powerful will bending hers in that blind persistence with which men and women believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature. A kind intention or a cruel intention made the act seem no less a crime as she looked upon it in that brief moment of illumination.”

Louise does not agree with the norms placed upon her by her society: she looks forward to “living for herself” rather than by the will of her husband or the institution of marriage, and she believes she will find happiness outside of where her society deems it appropriate to do so. Chopin continues, through narration, imagery, and figurative language , to fully develop Louise into a complex character. Assume that this is the case with every piece of literary fiction you read, and analyze accordingly.

All Roads Lead to Tone and Irony

This is where finding the overall meaning of the text is important again: you have to know an author’s tone towards a subject or person before you can determine meaning. Does the author have a positive or negative tone towards a social norm or idea? How does the author show this tone through their diction (word choice)?

In “The Story of an Hour,” Chopin displays her negative tone towards marriage in the following line:

“There would be no powerful will bending hers in that blind persistence with which men and women believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature.”

We can infer Chopin’s negative tone through words such as “blind persistence,” which imply that men and women of her time followed a norm without fully seeing or understanding its reasoning, and through the phrase “believe they have a right,” implying that people believe, but do not actually hold, the right towards another “fellow-creature.”

So, we know that Chopin does not see marriage as a positive institution. As a result, we know her overall purpose includes showing her readers this idea, and that any part of her story that portrays marriage in a positive light is likely to be ironic. You can do this same exercise (with more examples to prove your point) with any short story you read

Ooh, the irony! Errr, remind me what that is again, exactly?

Irony breeds in short stories: they are an excellent medium to show an author’s often divisive view of a social norm, stereotype, or relationship. Short stories move through a plot quickly, allowing an author to get to an ironic ending or description more quickly than in a novel or play. Missing an author’s ironic tone or plot twist can result in a misreading of the text and misanalysis on the exam.

Yikes! So, how do we make sure we spot irony in a short story ?

First of all, remember that something is ironic when the reader expects one outcome, and the opposite happens. We see irony appear in three different forms:

Verbal Irony: The author or a character says something, but means the opposite. (A lot of people call this being “sarcastic.” Sarcasm is a type of irony, but involves being cruel on purpose, whereas irony is not always cruel.)

Example: “[Selling babies for eating] would increase the care and tenderness of mothers towards their children...” - Jonathan Swift, “A Modest Proposal” (He definitely means the opposite of what he is saying. Trust me.)

Situational Irony: The reader expects one event or ending, but the opposite occurs.

Example: Instead of being happy about her husband’s appearance after believing him dead, Louise dies of heart failure at the end of “The Story of an Hour.”

Dramatic Irony : The reader knows something the characters in the story do not.

Example: The doctors proclaimed that Louise died of “heart disease - of the joy that kills” at the sight of her husband. We, the audience, know she died of shock and horror at her husband’s appearance.

Irony can be notoriously hard to spot in written texts. Why? Because our markers for irony, especially verbal irony, are just that: verbal. We listen for our friend’s tone of voice when they say they’re having a “great day” (is it actually great, or are they miserable and being ironic?). Unfortunately, we have yet to invent a special font for irony, so we have to look for other aspects in a short story to find it:

- Tone : See the explanation at the beginning of this section.

- Context: What is the author discussing in the short story ? For example, we know that the ending of “The Story of an Hour” is dramatically ironic because we go the context that Louise wants to be free of her marriage, not back in it. If something doesn’t make sense with the rest of the plot or descriptions from the story, go back and re-read it with an ironic tone in mind, and it may come together.

- Hyperbole: Are other parts of the text, like descriptions of characters or situations, exaggerated to an extreme degree? Do you see stereotypes in a piece of fiction? It’s likely that the author is attempting to ridicule and subvert these norms and stereotypes through exaggeration and irony.

- Diction: Word choice ties into context and hyperbole. How is the author describing particular characters and situations? Are the words the author chooses portraying something in a positive or negative light? Do they exaggerate a situation? Diction will also indicate tone , which will indicate whether or not an author is being ironic.

Thematic Analysis of a Short Story

So, now you have the tools to annotate and mark the important aspects of a short story for analysis, and you know what to look for. Now, what do you do with this evidence, and how will you use it on the exam?

As explained in the separate sections above, you will use whatever you find in the short story to support your thesis statement that you create based on the prompt you receive in the Free Response section of the exam. When you do timed writing, keep these tips in mind:

- DO read and mark the entire prompt before diving into the story. This way, you’ll narrow down what you’re analyzing.

- DO consider the what, how, and why of an author’s literary choices ( tone , literary devices , characterization , etc.). High scores on AP Lit essays are built on diving into the “whys” of the stories, not just the “whats.”

- DON’T feel like you need to mark and find every single literary device or super-secret symbol in the story. Focus on what you need to prove your thesis, and only your thesis.

You will also use short story excerpts for the Multiple Choice section of the exam. Many of the same strategies remain as for the Free Response analysis:

- Read through the questions before reading the story. Mark any lines or passages that the questions ask you to analyze specifically.

- Annotate for comprehension and clarity (using summary and paraphrase).

- The questions will ask for the whats, hows, and whys of a story and the author’s choices - be sure to look and mark for all three as you annotate.

For either section, the best things you can do for yourself are READ WIDELY and PRACTICE using past AP Lit prompts, multiple-choice questions, and good, dense examples of literary short stories.

Some good, dense literary short stories for practice (and enjoyment!)

Want to work your analysis chops on short stories, but don’t know where to begin? Here is a non-exhaustive list of good, dense literary short stories to dive into and practice the skills detailed in this guide. As a caution, much literary fiction by nature contains mature content and controversial subject matter; feel free to look up a synopsis of any short story to determine if the story is right for you:

“This is What it Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona” by Sherman Alexie

“The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

“The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Gilman

“Hill Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway

“Sweat” by Zora Neale Hurston

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

“Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” by Joyce Carol Oates

“The Things They Carried” by Tim O’Brien

“A Good Man is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor

“Revelation” by Flannery O’Connor

“The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe

Key Terms to Review ( 11 )

Characterization

Complex Relationships

Dramatic Irony

Figurative Language

Literary Devices

Literary Fiction

Overall Meaning

Short Story

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

48 Writing About Short Fiction

Dr. Karen Palmer

Analysis means to break something down in order to better understand how it works. To analyze a literary work is to pull it apart and look at its discrete components to see how those components contribute to the meaning and/or effect of the whole. Thus, a literary analysis argument considers what has been learned in analyzing a work (What do the parts look like and how do they function?) and forwards a particular perspective on their contribution to the whole (In light of the author’s use of diction, for example, what meaning does the novel, as a whole, yield?).

When writing a critical theory paper, your goal is to bring out a deeper meaning in a text through the application of a critical theory. For instance, you might show how an author illustrates the status of women in a particular time period (as in “The Story of an Hour”) or how a short story’s focus on money or status highlights a disparity between the classes (“The Necklace”).

Your own findings from your analysis of the primary text should be a priority in your interpretation of the work. Analytical skills are invaluable as you explore any subject, investigating the subject by breaking it down and looking closely at how it functions. Finding patterns in your observations, then, helps you to interpret your analysis and communicate to others how you came to your conclusions about the subject’s meaning and/or effect. As you make your case to the readers, it is crucial that you make it clear how your perspective is relevant to them. Ideally, they will come away from your argument intrigued by the new insights you have revealed about the subject.

Step 5: Researching

Although analysis is a crucial phase in writing about any subject, the next step of contributing to society’s knowledge and understanding is to participate in the scholarly dialog on the subject. The dialog among scholars, conveyed through academic articles and books, is a crucial resource for any researcher.

Regardless of the type of critical lens you are using for your paper, discovering more about the author of the text can add to your understanding of the text and add depth to your argument. Author pages are located in the Literature Online ProQuest database. Here, you can find information about an author and his/her work, along with a list of recent articles written about the author. This is a wonderful starting point for your research.

The next step is to attempt to locate an article about the text itself. It’s important to narrow down your database choices to the Literature category. In some cases, the options will be numerous. You can narrow down the choices by adding your critical lens to the search terms. ie “Story of an Hour” and feminism

In the case that your results are very limited, you might need to think outside of the box. Look for the author’s name and your critical theory. It’s possibly that articles have been written about another of the author’s pieces that can still add to your project. Another option is to search the full ProQuest database or the newspaper databases. Some periodicals publish literary criticism and reviews. Since they are popular, rather than academic, sources, these may be found in the periodical databases, rather than the literature options.

Another option is to search for an article relating to the critical lens you’ve chosen. For example, you might look for an article on the key elements of feminist literary criticism or on Freud’s id, ego, and superego to help you support your argument.

Finally, you might look for articles pertinent to an issue discussed in the short story. For example, “The Yellow Wallpaper” is about the treatment of post-partum depression. A modern day article on the appropriate treatment for this illness or a survey of the treatment of the illness could be a fantastic addition to your paper.

Remember, it is helpful to keep a Research Journal to track your research. Your journal should include, at a minimum, the correct MLA citation of the source, a brief summary of the article, and any quotes that stick out to you. A note about how you think the article adds to your understanding of the topic or might contribute to your project is a good addition, as well.

Step 6: Creating a Thesis and Outline

By the time you have completed an analysis of the story and finished your research, you should have a pretty clear idea about what you want to say about the text you’ve chosen. Your thesis should convey the main point you want to make about the story as viewed through the lens you chose. Perhaps you are looking at “The Yellow Wallpaper” through a feminist lens. Perhaps you want to call attention to the fact that women’s voices were unheard in their battles with post-partum depression. Your thesis might say something like, “Gilman used her short story to highlight the inappropriate and often harmful treatment women suffering from post-partum depression received and, in so doing, advocated for women’s voices to be heard.”

Once your argument is in place, the next step is to create an outline of your paper. Remember–your outline is like the skeleton of your paper. Without a solid foundation, your argument will not work properly.

One common misconception students entertain when they approach literary analysis essays is the idea that the structure of the essay should follow the structure of the literary work. The events of short stories, novels, and plays are often related chronologically, in linear order from the moment when the first event occurs to the moment of the last. Yet, it can be awkward to write a literary analysis using the story’s chronology as a basic structure for your own essay. Often, this approach leads to an essay that simply summarizes the literary work. Since a literary analysis paper should avoid summary for summary’s sake, the writer should avoid an essay structure that results in that pattern.

If chronology is not the primary structural factor in setting up a literary analysis paper, what is? You might consider the following hints in arranging the points of your own essay:

- What are your major points?

- What order will most effectively lead the reader to your perspective on this subject?

- Paragraph breaks should (a) cue the reader regarding shifts in focus and (b) break down ideas into small enough chunks that the reader does not lose sight of the currently emphasized point. On the other hand, in an academic essay, the paragraphs should not seem “choppy.” Rather each should be long enough to develop its point thoroughly before shifting to the next.

In most cases, a literary analysis outline will have the following parts:

- Introduction (hook, topic, thesis)

- Summary of the work and background of the author

- Argument (at least three points)

Here is a complete student outline for the story, “Everything in This Country Must,” by Colum McCann.

- Thesis: In “Everything in This Country Must” the author reveals the effect that grief can have on someone through the use of terminology, relationships, imagery, irony, and paradox.

- Born in Dublin, Ireland February 28 th , 1965.

- He was a reporter.

- He is a Creative Writing Professor at Hunter College.

- When was it written?

- What time is it based in?

- A short synopsis on what it is about.

- Soldiers use expletives. A true reflection of soldiers here.

- Contrast between American perception on certain words, versus what they mean in the United Kingdom.

- What Katie calls the soldiers. For the readers’ benefit and humor.

- Father’s relationship with Mammy and Fiachra.

- Father’s relationship with Katie.

- Father’s relationship with the draft horse.

- Father’s relationship with the soldiers.

- The soldiers’ relationship with each other.

- The vivid descriptions and the extensive use of simile.

- The darkness and rain seem to reflect the mood of the story. (Note: the very last sentence of the story.)

The British soldiers, (possibly the same ones who killed Mammy and Fiachra in a car accident) are the object of all the father’s loathing and blame. But they are also the savior of his favorite horse.

The entire story is based on saving the draft horse. At the end of the story, though, the father shoots it, and it dies. Why would he do that?

9. Conclusion:

Colum McCann reveals to the reader the innate and devastating effect grief can have on even the best of people. He does this in a beautiful short story and accomplished this through terminology, relationships, imagery, irony, and paradox.

Watch this video with some additional tips for creating an outline:

Step 7: Drafting

Writing an introduction.

The formula for a successful introduction for a literary analysis essay should feel very familiar to you. Your first task as a writer is to draw your readers into your essay by connecting their own experiences with the topic of your paper. This is accomplished by a hook that relates to your readers and draws them into your argument. For example, if you were writing about the treatment of post-partum depression in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” you might begin your paper with a statistic about the number of women who experience it. This statistic shows readers that your topic has significance to a modern issue and possibly to their own lives, as well.

Once you’ve successfully hooked your audience, you should transition into your topic. In this case, you’ll need to give your readers the author and title of the piece you are discussing. For example, you might say something like, “Post-partum depression is nothing new. In fact, Charlotte Perkins Gilman addresses the improper treatment of post-partum depression in her short story, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper.'” This sentence provides a bridge from the hook to the thesis.

Finally, your introduction should include a strong statement of your argument. “Gilman used her short story to highlight the inappropriate and often harmful treatment women suffering from post-partum depression received and, in so doing, advocated for women’s voices to be heard.” This final piece of the introduction leaves no doubt about the essay’s argument.

Remember that, while there are three key parts to an introduction, this does not mean that you will only have three sentences in your introductory paragraph.

Background Information

When writing an analysis of a short story, it’s important to consider your readers’ experience with the text. In general, you should assume that the reader is familiar with the short story, but that it may have been awhile since they have read it. Therefore, including a brief summary of the plot of the text is an important part of ensuring that your readers can follow your argument.

Here are some basic tips for writing a summary:

- Begin with an introductory sentence that states the text’s title, author and main thesis or subject.

- Write in your own words–do not include quotes.

- In less than five sentences, tell readers the general plot of the story, including key characters, events, and ideas.

- Do not insert any of your own opinions, interpretations, deductions or comments into a summary.

Depending on the type of analysis you are writing, the information about the author might also be an important element to include in your background section. This could be as simple as a single sentence telling readers when the piece was written or as complex as a short paragraph describing the historical and cultural context of the piece.

Body Paragraphs

Remember that your body paragraphs have three key components:

- Topic sentence that tells readers what point you will be discussing in the paragraph and relates back to the thesis. The topic sentence is also where you would include a transition from the previous paragraph.

- Support/Evidence for your point from the story, following the Quote Formula .

- Wrap up the paragraph by explaining to readers how the evidence you’ve provided proves your point.

Here’s a brief video explaining these the parts of a body paragraph in a literary analysis essay:

Here’s a brief video recapping the process of writing a literary analysis of the short story, “Story of an Hour”:

Incorporating Secondary Sources

One of the keys to a successful literary analysis is engaging in the academic conversation about the author and the work you’ve chosen. This means that you should incorporate your secondary sources into your analysis, as well as the primary text you are studying. Look for areas where an expert voice will help to strengthen the argument you are making in your paper. Since you’ve built your argument on your own analysis in combination with your research, this should be a fairly straightforward process. Remember to always surround quotes with your own words and follow the Quote Formula !

Conclusions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate your drafted conclusions, and suggest conclusion strategies to avoid.

ABOUT CONCLUSIONS

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. While the body is often easier to write, it needs a frame around it. An introduction and conclusion frame your thoughts and bridge your ideas for the reader.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

STRATEGIES FOR WRITING AN EFFECTIVE CONCLUSION

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion.

Friend: Why should anybody care?

You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally.

You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize: Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help her to apply your info and ideas to her own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

STRATEGIES TO AVOID

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

FOUR KINDS OF INEFFECTIVE CONCLUSIONS

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.