Value Education Topics: Exploring the Importance

Value education plays a crucial role in shaping individuals and societies. It involves imparting moral, ethical, and social values to individuals equipping them with the necessary tools to navigate life.

The need for value education has become more pronounced in today’s fast-paced and ever-changing world. By understanding the value education’s core principles and significance, we can create a better society for future generations.

Value education encompasses cultivating positive values such as honesty, empathy, respect, responsibility, and compassion. It aims to develop individuals who excel academically and exhibit strong moral character.

By instilling these values, we can foster a sense of social cohesion, empathy, and ethical decision-making in individuals, enabling them to contribute positively to society.

Table of Contents

The Importance of Value Education in Today’s Society

In today’s society, where individuals are constantly bombarded with conflicting messages and faced with complex ethical dilemmas, value education is paramount. Value education provides a moral compass, guiding individuals to make ethical choices and contribute positively to their communities.

It equips individuals with the skills and knowledge to navigate through the challenges of life, fostering personal growth and resilience.

Moreover, value education helps in building a harmonious and inclusive society. By promoting respect, tolerance, and empathy, individuals learn to appreciate diversity and coexist peacefully with people from different backgrounds.

This fosters a sense of unity and social cohesion, which is crucial for the progress and development of any society.

Value Education Topics for Degree Students

For degree students, value education topics can be tailored to their needs and aspirations. These topics should focus on preparing students for their future careers while nurturing their moral character. Some essential value education topics for degree students include:

Ethics in the Workplace: Examining ethical dilemmas and decision-making in professional settings.

Leadership and Integrity: Exploring the qualities of effective leadership and the importance of integrity in the workplace.

Social Responsibility: Understanding the role of individuals and organizations in addressing social issues and contributing to the betterment of society.

Sustainable Development: Promoting awareness and understanding of sustainable practices to create a more environmentally conscious society.

Global Citizenship: Encouraging students to become responsible global citizens by understanding and appreciating diverse cultures and perspectives.

Incorporating Value Education and Life Skills Topics

Value education goes hand in hand with the development of life skills. Life skills are essential abilities that enable individuals to cope with the challenges of everyday life effectively. When combined with value education, life skills topics enhance personal growth and empower individuals to navigate various situations confidently and resiliently.

Some value education and life skills topics that can be incorporated include:

- Emotional Intelligence: Developing self-awareness, empathy, and practical communication skills to build healthy relationships.

- Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving: Encouraging analytical thinking and the ability to find creative solutions to complex problems.

- Decision-Making: Teaching individuals to make informed decisions by considering ethical implications and long-term consequences.

- Conflict Resolution: Equipping individuals with the skills to resolve conflicts peacefully and promote positive dialogue.

- Stress Management: Providing strategies to manage stress and maintain mental well-being effectively.

Topics for Value Education in Schools

Schools play a pivotal role in shaping the values and character of young minds. By incorporating value education into school curricula, we can instill positive values in students from an early age, creating a strong foundation for their personal and social development. Some topics that can be included in value education in schools are:

- Respect for Others: Teaching students to respect and appreciate the diversity of cultures, beliefs, and opinions.

- Kindness and Empathy: Promoting acts of kindness and empathy towards others, fostering a supportive and inclusive school environment.

- Responsible Citizenship: Educating students about their rights and responsibilities as citizens, and the importance of active participation in their communities.

- Environmental Awareness: Encouraging students to be environmentally conscious and promoting sustainable practices.

- Ethical Use of Technology: Teaching students about the responsible and ethical use of technology, including cyberbullying prevention and digital etiquette.

Promoting Value-Based Education Topics

Promoting value-based education topics requires a multifaceted approach involving educational institutions, policymakers, parents, and the wider community. Together, we can create an environment that fosters the development of strong moral character and values in individuals.

Educational institutions can promote value-based education by:

- Integrating value education into their curricula across all levels of education.

- Providing professional development opportunities for teachers to incorporate value education topics into their teaching practices effectively.

- Creating a supportive and inclusive school culture that emphasizes values such as respect, empathy, and integrity.

- Collaborating with parents and the community to reinforce value education principles beyond the classroom.

Policymakers play a crucial role in promoting value education by:

- Recognizing the importance of value education and integrating it into educational policies and frameworks.

- Allocating resources and support for implementing value education programs in schools and universities.

- Collaborating with educational institutions and stakeholders to develop comprehensive value education guidelines.

Parents can contribute to promoting value education by:

- Reinforcing positive values at home and modeling ethical behavior for their children.

- Engaging in open conversations with their children about moral and ethical dilemmas.

- Encouraging community service and volunteering activities to promote values such as empathy and social responsibility.

By working together, we can create a society that values and prioritizes the development of strong moral character and ethical behavior.

Exploring Various Topics on Value Education

Value education is a vast field with a multitude of topics that can be explored. The topics can be tailored to different age groups and contexts. Some other topics on value education include:

Gender Equality: Promoting awareness and understanding of gender equality, challenging stereotypes, and promoting inclusivity.

Human Rights and Social Justice: Educating individuals about human rights issues and the importance of social justice in creating an equitable society.

Integrity and Honesty: Cultivating a culture of integrity and honesty, emphasizing the importance of ethical behavior in personal and professional life.

Cultural Appreciation and Diversity: Encouraging individuals to appreciate and respect diverse cultures, fostering a sense of unity and harmony.

Civic Responsibility: Educating individuals about their civic responsibilities and encouraging active participation in democratic processes.

Implementing Value Education in Different Settings

Value education can be implemented in various settings beyond traditional educational institutions. By extending value education to workplaces, community organizations, and other contexts, we can create a society where ethical behavior and moral values are upheld.

In workplaces, value education can be integrated through:

- Ethical Codes of Conduct: Developing and implementing ethical codes of conduct to guide employees’ behavior and decision-making.

- Training and Workshops: Providing training programs and workshops on ethical decision-making, conflict resolution, and fostering positive workplace relationships.

- Leadership Development: Incorporating value education topics into leadership development programs to foster ethical leadership and organizational culture.

In community organizations, value education can be promoted through:

- Workshops and Seminars: Organizing workshops and seminars to raise awareness about values such as empathy, compassion, and social responsibility.

- Community Service: Encouraging community service activities that promote values and contribute to the well-being of society.

- Collaborations and Partnerships: Collaborating with educational institutions, businesses, and other organizations to develop comprehensive value education programs.

Resources for Value Education Topics

Numerous resources are available to support the teaching and learning of value education topics. These resources can aid educators, parents, and individuals in exploring and understanding different aspects of value education. Some valuable resources include:

Books and Literature: There are numerous books, stories, and novels that explore moral and ethical themes, providing valuable insights and discussions.

Online Platforms and Websites: Websites dedicated to value education provide lesson plans, activities, and resources for educators and parents.

Educational Videos and Documentaries: Engaging videos and documentaries can be used to initiate discussions and explore value education topics.

Workshops and Training Programs: Participating in workshops and training programs focused on value education can enhance knowledge and skills in this area.

Community Organizations and NGOs: Collaborating with community organizations and NGOs can provide access to valuable resources and expertise in value education.

Conclusion: The Impact of Value Education on Society

Value education is crucial in shaping individuals and societies. By imparting moral, ethical, and social values, we can create a society where individuals exhibit strong character, empathy, and responsible citizenship. The importance of value education in today’s society cannot be overstated.

Through value education , we can foster a sense of social cohesion, promote positive values, and create a more inclusive and equitable society. By incorporating value education topics into educational curricula, workplaces, community organizations, and other settings, we can ensure that individuals are equipped with the necessary tools to navigate through life with integrity and compassion.

About The Author

Website Developer, Blogger, Digital Marketer & Search Engine Optimization SEO Expert.

See author's posts

Related Posts

Is Psychology A Social Science Or Natural Science: Overview

Why Is Educational Psychology Important

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Join CollegeSearch Family

Monthly Users

Monthly Applications

Popular Colleges by Branches

Trending search.

Top MBA Colleges in Delhi/NCR

Top MBA Colleges in Bangalore

Top Engineering Colleges in Delhi/NCR

Top Engineering Colleges in Bangalore

No Result Found

Popular Branches

Home > News & Articles > Importance of Value Education: Aim, Types, Purpose, Methods

Samiksha Gupta

Updated on 06th January, 2023 , 8 min read

Importance of Value Education: Aim, Types, Purpose, Methods

Importance of value education overview.

Value-based education places an emphasis on helping students develop their personalities so they can shape their future and deal with challenges with ease. It shapes children to effectively carry out their social, moral, and democratic responsibilities while becoming sensitive to changing circumstances. The importance of value education can be understood by looking at its advantages in terms of how it helps students grow physically and emotionally, teaches manners and fosters a sense of brotherhood, fosters a sense of patriotism, and fosters religious tolerance.

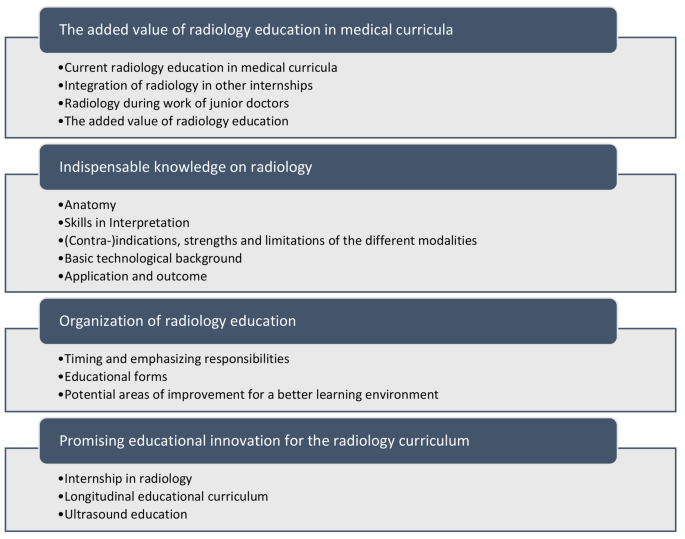

What is Value Education?

"Value education" is the process through which people impart moral ideals to one another. Powney et al. define it as an action that can occur in any human organization. During this time, people are assisted by others, who may be older, in a condition they experience in order to make explicit our ethics, assess the effectiveness of these values and associated behaviors for their own and others' long-term well-being, and reflect on and acquire other values and behaviors that they recognize as being more effective for their own and others' long-term well-being. There is a distinction to be made between literacy and education.

Goals of Importance of Value Education

This notion refers to the educational process of instilling moral norms in order to foster more peaceful and democratic communities. Values education, therefore, encourages tolerance and understanding beyond our political, cultural, and religious differences, with a specific emphasis on the defense of human rights, the protection of ethnic minorities and vulnerable groups, and environmental conservation.

Importance of Value Education

Value education ought to be integrated into the educational process rather than being considered a separate academic field. The value of value education can be understood from many angles. The following are some reasons why value education is essential in the modern world-

- It aids in making the right choices in challenging circumstances, enhancing decision-making skills.

- It cultivates important values in students, such as kindness, compassion, and empathy.

- Children's curiosity is sparked, their values and interests are developed, and this further aids in students' skill development.

- Additionally, it promotes a sense of brotherhood and patriotism, which helps students become more accepting of all cultures and religions.

- Due to the fact that they are taught about the proper values and ethics, it gives students' lives a positive direction.

- It aids students in discovering their true calling in life—one that involves giving back to society and striving to improve themselves.

- A wide range of responsibilities come with getting older. Occasionally, this can create a sense of meaninglessness, which increases the risk of mental health disorders, midlife crises, and growing dissatisfaction with one's life. Value education seeks to fill a void in peoples' lives in some small way.

- Additionally, people are more convinced and dedicated to their goals and passions when they learn about the importance of values in society and their own lives. This causes the emergence of awareness, which then produces deliberate and fruitful decisions.

- The critical role of value in highlighting the execution of the act and the significance of its value, education is highlighted. It instils a sense of ‘meaning' behind what one is supposed to do and thus aids in personality development.

Also read more National Education Day and Women's Education in India .

Purpose of value education.

Value education is significant on many levels in the modern world. It is essential to ensure that moral and ethical values are instilled in children throughout their educational journey and even after.

The main goals of value education are as follows:

- To make sure that a child's personality development is approached holistically, taking into account their physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs

- Instilling a sense of patriotism and good citizenship values

- Educating students about the value of brotherhood at the social, national, and global levels

- Fostering politeness, accountability, and cooperation

- Fostering a sense of curiosity and inquiry about orthodox practices

- Teaching students how to make moral decisions and how to make good decisions

- Encouraging a democratic outlook and way of life

- Teaching students the value of tolerance and respect for people of all cultures and religions.

Read more about the Importance of Books and Distance Education Universities .

Scope of value education.

The scope of value education is as follows-

- To make a positive contribution to society through good living and trust.

- Moral education, personality education, ethics, and philosophy have all attempted to accomplish similar goals.

- Character education in the United States refers to six character education programs in schools that try to teach key values such as friendliness, fairness, and social justice while also influencing students' behavior and attitudes.

Also read more Best Distance Education Institutes .

Types of value education, cultural value.

Cultural values are concerned with what is right and wrong, good and evil, as well as conventions and behavior. Language, ethics, social hierarchy, aesthetics, education, law, economics, philosophy, and many social institutions all reflect cultural values.

Moral Value

Ethical principles include respecting others' and one's own authority, keeping commitments, avoiding unnecessary conflicts with others, avoiding cheating and dishonesty, praising people and making them work, and encouraging others.

Personal Values

Personal values include whatever a person needs in social interaction. Personal values include beauty, morality, confidence, self-motivation, regularity, ambition, courage, vision, imagination, and so on.

Spiritual Value

Spiritual worth is the greatest moral value. Purity, meditation, yoga, discipline, control, clarity, and devotion to God are examples of spiritual virtues.

Spiritual value education emphasizes self-discipline concepts. satisfaction with self-discipline, absence of wants, general greed, and freedom from seriousness.

Social Value

A person cannot exist in the world unless they communicate with others. People are looking for social values such as love, affection, friendship, noble groups, reference groups, impurity, hospitality, courage, service, justice, freedom, patience, forgiveness, coordination, compassion, tolerance, and so on.

Universal Value

The perception of the human predicament is defined by universal ideals. We identify ourselves with mankind and the universe through universal ideals. Life, joy, fraternity, love, sympathy, service, paradise, truth, and eternity are examples of universal values.

Importance of Value Education in School

The inclusion of value education in school curricula is crucial because it teaches students the fundamental morals they need to develop into good citizens and individuals. Here are the top reasons why valuing education in school is important:

- Their future can be significantly shaped and their ability to discover their true calling in life can be helped by value education.

- Every child's education begins in school, so incorporating value-based education into the curriculum can aid students in learning the most fundamental moral principles from the very beginning of their academic careers.

- Value education can also be taught in schools with a stronger emphasis on teaching human values than memorizing theories, concepts, and formulas to get better grades. The fundamentals of human values can thus be taught to students through the use of storytelling in value education.

- Without the study of human values that can make every child a more kind, compassionate, and empathic person and foster emotional intelligence in every child, education would undoubtedly fall short.

Importance of Value Education in Personal Life

We all understand the value of education in our lives in this competitive world; it plays a crucial part in molding our lives and personalities. Education is critical for obtaining a good position and a career in society; it not only improves our personalities but also advances us psychologically, spiritually, and intellectually. A child's childhood ambitions include becoming a doctor, lawyer, or IAS official. Parents desire to picture their children as doctors, lawyers, or high-ranking officials. This is only achievable if the youngster has a good education. As a result, we may infer that education is extremely essential in our lives and that we must all work hard to obtain it in order to be successful.

How Does Value Education Help in Attaining Life Goals

Education in values is crucial for a person's growth. In many ways, it benefits them. Through value education, you can achieve all of your life goals, and here's how:

- It helps students know how to shape their future and even helps them understand the meaning of life.

- It teaches them how to live their lives in the most advantageous way for both themselves and those around them.

- In addition to helping students understand life's perspective more clearly and live successful lives as responsible citizens, value education also helps students become more and more responsible and sensible.

- Additionally, it aids students in forging solid bonds with their relatives and friends.

- enhances the students' personality and character.

- Value-based education helps students cultivate a positive outlook on life.

What are the types of value education opportunities?

After understanding the significance of this important topic, the next step is choosing the type that best meets your needs. The teaching of values can start at a young age (in primary school) and continue through higher education and beyond. Understanding the various opportunities available to you will make it easy to find the right fit.

Early Age Training

Value education is now being taught in many primary, middle, and high schools all over the world. The best way to learn the skills taught in this training is to be taught how important it is from a young age.

Student Exchange Programs

One of the best ways to teach students about values and foster a sense of responsibility in them is through student exchange or gap year programs. Student exchange programs are another exceptional way to experience various cultures and broaden your understanding of how people behave and function. This is a fantastic chance for first- and second-year undergraduate students.

Workshops for Adults

People who are four to five years into their careers frequently show signs of irritation, unhappiness, fatigue, and burnout, which is a worrying statistic worth noting. As a result, the relevance and significance of education for adults is a notion that is currently steadily gaining support within the global community.

Methods of Teaching Value Education

Teaching value education can be done using a variety of methodologies and techniques. Four of the many are the most frequently used. They are

- Methods used in classroom instruction include direct instruction, group discussions, reading, listening, and other activities.

- This method includes a practical description of the strategies. It is an activity-based method. This practical knowledge improves learning abilities and helps people live practical lives on their own.

- Socialized techniques: These involve the learner participating in real-world activities and encounters that simulate the roles and issues that socialization agents face.

- The incident learning approach enables the examination of a particular event or encounter in the history of a particular group.

Related Articles-

Traditional education vs. value education.

Both traditional education and values education are important for personal development since they help us establish our life goals. However, although the former educates us about social, scientific, and humanistic knowledge, the latter teaches us how to be decent citizens. In contrast to traditional education, there is no separation between what happens inside and outside the classroom in values education.

Key takeaways

- The discipline of value education is essential to the overall growth and learning of students.

- You can acquire all the necessary emotional and spiritual tools for use in a variety of situations by realizing its significance.

- You can apply the lessons over the course of your academic career. Additionally, there are special education options available for a particular age group.

- One of the best ways to get the most out of your educational experience is to combine the two types of value education training.

- It's also crucial to remember that value education is a continuous process that extends outside of the classroom.

Was this Article Helpful/Relevant or did you get what you were looking for ?

👍 1,234

👎234

Similar Articles

JoSAA Counselling 2024

D Pharmacy: Admission 2024, Subjects, Colleges, Eligibility, Fees, Jobs, Salary

How to Become a Pilot after 12th: In India, Courses, Exams, Fees, Salary 2023

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 5 main values of education.

Ans. There are five fundamental approaches to values education, according to Superka, Ahrens, and Hedstrom (1976): inculcation, moral development, analysis, values clarification, and action learning.

What is value education?

Ans. An individual develops abilities, attitudes, values, and other types of positive behavior depending on the society he lives in through the process of value education.

Why is value education important?

Ans. Every person must ensure a holistic approach to the development of their personality in regard to the physical, mental, social, and moral aspects. It gives the students a constructive direction in which to mold their future, assisting them in growing in maturity and responsibility and in understanding the meaning of life.

Does value education increase emotional intelligence (EQ)?

Ans. Yes, value education has been shown to boost emotional intelligence (particularly when given at a young age). For a variety of personal, academic, and professional opportunities, EQ is a crucial factor that is evaluated.

Will I learn how to socialize better if I study value education?

Ans. Yes, you will. You can develop a fresh perspective on people and groups from various communities and professions with the aid of value education. This aerial perspective of various people is a great way to hone your socialization abilities.

Similar College

Apply Before Dec 16

ICFAI Business School (IBS) Mumbai - Maharashtra

Course Offered

Fees for 2 years, avg. package, highest package.

ICFAI Business School (IBS) Pune - Maharashtra

PDF Preview

Popular searches, popular colleges/universities, top colleges by courses, top courses.

Value Education: Meaning, Importance, Benefits

Academic education and value education are virtually intertwined; hence, they are equally important. Without the former, nobody will be able to learn skills such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. One cannot secure a good job or manage even the simplest daily essentials if they do not know how to behave properly with others.

Understand Value Education

Meaning of value education.

Considering Value Education as a compound word, the separate definitions of both the terms “value” and “education” are presented. This leads to the definition of Value Education as the process of transmitting values to the pupils.

According to K. H. Imam Zarkasy, Value Education is an educational action or the conveying of knowledge on the measurement of morality, and showing the difference between what is bad and good for living in society.

The various aspects of Value Education include Moral Education, Civic Education, Citizenship Education, Environmental Education, Religious Education, and Spiritual Education.

Educators worldwide have initiated various steps, packages, projects, and discussions at their respective levels for promoting values.

Some names that could be mentioned here include:

- Holistic Approach to Education

- Global Education

- Value-Based Education (VBE)

- Democratic Education

- Character Education

- Home School System

- Alternative Education

- Philosophy for Child (P4C)

- Islamization of Knowledge (IOK)

- Moral Education

- Project/Problem-Based Learning (P2BL)

- TLC (Teaching and Learning Center)

- Anchored Instruction

- Interdisciplinary Approach

- Enquiring Minds

- Living Values Education Programme (LVEP)

Importance of Value Education

The importance of balancing material and moral values.

Everything a person does has little meaning and will not serve them well. Therefore, for our welfare, as well as that of others, both academic excellence and value education must be combined.

Even during good times, the finer things in life, such as a high reputation, fame, and money, can make a person arrogant unless they know how to use money and power correctly. The absence of these very attributes can destroy their glory and honor.

If we possess many talents, wealth, power, or fame in life, we must learn to use them wisely so that both ourselves and others may find happiness by leading a life guided by both moral values and material riches.

Addressing Global Challenges Through Value Education

World citizens are facing numerous problems, including terrorism, drug addiction, poverty, and overpopulation.

Hence, it is necessary to instill moral values in the curriculum because education is a highly effective weapon to combat these evils and find solutions. “Education is a weapon, whose effect depends on who holds it in their hand and at whom it is aimed” (Joseph Stalin).

Shaping the Future Through Education

We know that today’s children are tomorrow’s citizens. If we provide a good education to today’s children, the future of the next generation will be well-informed. Education is the key to solving all types of these problems .

Embracing Modernity with Moral Values

We are living in a modern century, and therefore, we must use science and technology in the proper way. It is not difficult for us to address all the issues related to non-moral or valueless matters. The primary objective of this study is to instill moral values in schools and colleges.

The Transformative Power of Education

Education possesses the genuine power to help learners shape their minds and manners accordingly, thus enabling the attainment of academic excellence in a fruitful and perfect manner.

Manifestation of Values

We see that Value Education has two aspects to be judged and appreciated, and these two are worth making life and living (1) useful and (2) satisfactory.

It is highly abstract and qualitative, and at the same time, relative in the context of the individual’s culture, creed, acquired belief, conviction, attitude, etc. “Many men, many minds,” and so there are astronomical varieties and kinds of value concepts of education among the peoples of the world.

Literary Illustrations of Value Differences

Now let us cite some examples from some celebrated works.

For instance, the classical playwright Shakespeare’s two characters in his famed drama “ The Merchant of Venice ” exhibit two sorts of values of a single thing – money.

To one protagonist, Antony, the value of money, so to say, lies in sacrifice to ameliorate the sufferings of the poor and the distressed, whereas his counterpart, Shylock, treats the same for multiplying it by usury practices if needed, heartlessly.

Though these two characters are literary creations, they actually represent the two characters of society that have existed since the creation of man, so to speak.

Diverse Cultural Perspectives on Values

Again, the story of Hatemtaye is a unique example that shows how a good soul was ready to have his own head chopped off for his poverty-stricken killer who came to kill him (Hatemtaye) to claim the prize money. According to blood, culture, education, belief, or religion, people of the world are contradictorily and even contrarily different and varied.

For instance, a Jewish, a Christian, a Hindu, a Buddhist, a Muslim, and even an Atheist express their distinct attitudes, manners, and behaviors that are not necessarily similar in respect of, say, greetings, eating habits, drinking, clothing, and observing ceremonies.

Contrasting Economic and Political Systems

To a Communist, a state is the master of the people, and each citizen of the communist country has to work for the welfare of the state according to their capability, and in return, the state will provide them with provisions according to their necessity.

As a result, the value of a person is determined by their physical strength and food, minus their soul, which survives on spiritual nourishment. In a capitalist country, earnings and spending have no moral or humanitarian constraints.

Philosophical Approaches to Values

Pragmatic thoughts and hedonistic philosophy are now influential in world politics. According to naturalists, an individual can get the greatest value out of life by harmonizing their life as closely as possible with nature.

Pragmatists deny the existence of ultimate eternal values and believe that all values are subjective and relative to humans.

They think that values constantly develop through the interplay between fresh personal experiences and cultural influences. Values like truth are rooted in and derived from their source; this is the belief of essentialists.

Spiritual Perspectives on Value

According to perennialists, not only knowledge but values are grounded in a teleological and supernatural reality. To them, beauty is the highest value in aesthetics, and speculative reason is the highest value in ethics.

They focus on teaching ideas that are everlasting, seeking enduring truths that are constant, as the natural and human worlds at their most essential level do not change. Sufis seek to gain spiritual illumination through deep meditation and attain an inner vision of the truth.

The Global Need for Value Education

So we see that with respect to politics, the forms of dictatorship, kingship, jingoistic nationalism, blood, territory, and color-based nationalism have been treated as useful and beneficial by the leaders of these categories.

Thus, the peoples of the present world are divided into several warring groups that now measure their power, prestige, and superiority based on their arms race and atomic energy. This means that the peace observed by these warring peoples is based on the balance of terror, not on the balance of goodwill.

This crucial global situation urgently requires Value Education. Changing such conflicting mindsets and behaviors, especially among the big powers, depends fundamentally on infusing education with morality, ethics, humanity , and other elements of Value Education.

A Critical Look into Value Education

Value Education is a very recent subject, considered for inclusion in general education courses, which had once been deeply rooted in early education. The average person dreams and believes that the primary aim of education is to meet the needs of parents facing socio-religio-economic and moral pressures.

Parental Aspirations in Education

Thus, we see that a farmer wants his son to become an expert in leading a farming life, a businessman hopes his son becomes a successful businessman capable of facing competition in this field, and similarly, a university teacher desires his child to become a distinguished intellectual figure, and so on.

All these notions of various parents or guardians express the desire to provide their children with better opportunities in life through education than they themselves have had.

Religious Foundations of Early Education

However, the history of education in the past shows that in ancient India, Europe, especially England, places of worship initially established common schools that accepted holy scriptures from people of different religions, making religion the core of moral training.

Shift Towards Secularism: The Renaissance Impact

This practice continued until the advent of the Renaissance between the 14th and 15th centuries, marked by the exploitation of science, technology, land discovery, economic resources, and other factors that significantly influenced human thinking, emphasizing pragmatism in life and society.

It diminished the importance of belief in God, religion, and divinity, rendering them almost insignificant and worthless.

Prominent Voices Against Religious Institutions

For instance, an American scholar named Thomas Pine expressed his personal viewpoint in his article ‘Profession of Faith’ in a manner that sophisticatedly disregarded religion.

He stated, ‘I believe in one God, and no more, and I hope for happiness beyond this life,’ asserting his belief as ‘My mind is my own church.’

Furthermore, he opined that ‘All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian, or Turkish (i.e., Muslims), appear to me no other than human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind and monopolize power and profit (F.B.G & A.P.H, 1974).’

Such a dismissive attitude toward God and religion is also evident in the views of individuals like Karl Marx , Darwin, and Einstein.

The Rise of Secular Societie

As a result, this godless perspective has transformed the current education system into one that is secular in both content and spirit. It has made belief in God and religion a personal matter of optional belief and ritual in society, including in state life and governance.

There is a belief that non-religious people demonstrate higher scores in acts of generosity and kindness, such as lending their possessions or offering a seat on a crowded bus, compared to religious individuals.

All these examples advocate that a society without God and with non-religious beliefs tends to perform better acts of service and goodwill for the community as a whole.

Consequences of a Godless Society

Hence, a secular society established through godless education has gained more ground than one influenced by religion. In such a society, a person’s life is seen as reaching its final and absolute end in death, with all their deeds, both good and bad, having no consequences in their future life or the next world.

A closer look at this dire situation of human life, devoid of religion, God, and divinity, reveals that it has occurred rapidly primarily due to the absence of value education in its true and real sense.

Value as the Base of Education

The authors, thinkers, educationists, and philosophers of world renown have been deeply grappling with the strong urge to establish morality as the foundation of all branches of education, which essentially constitutes Value Education.

Historical Perspectives on Morality in Education

Aristotle and later other renowned figures such as Locke, Hume, and Bertrand Russell held the opinion that moral objectives should be incorporated into education to curb humanity’s relentless pursuit of money, wealth, and power.

They believed that without acquiring these elements, life on this mortal earth would lead to a painful and meaningless end.

Life’s Purpose Beyond Materialism

These types of individuals, lacking faith in God or any form of religion, believe that life’s growth occurs here, both in power and wealth, with the ultimate goal of finding fulfillment in this material world.

The Need for Moral Aims in Education

Let us, therefore, critically examine the question: Why should education have moral aims, and how can these aims be implemented?

6 Benefits of Moral Objectives in Education

It is an acknowledged fact that the moral objectives of education have the effective capacity to control humanity’s inclination towards selfish rationality in pursuing personal enjoyment.

Studies on such tendencies or drives demonstrate that:

Achieving Excellence Through Virtue

The cultivation of virtue, the establishment of moral habits or values, allows individuals to achieve the highest quality and excellence in their character.

Philosopher Kant referred to it as ‘a good will,’ a concept acknowledged in all physical, intellectual, and aesthetic aspects of culture that helps individuals attain moral excellence.

The Role of Socialization in Education

Every child should receive proper training for social interaction and friendship. ‘Society is a human creation’ that necessitates socialization and the subordination of the self to uphold the golden rule ‘Live and Let Live,’ which thrives on love, politeness, sympathy, sacrifice, empathy, etc.

Promoting Peace and Prosperity Through Education

To achieve and maintain socio-religious, cultural, economic, and political peace and prosperity, every child should be educated, both in theory and practice, to fulfill these essential societal requirements.

The Growth and Development of Value-Education

Value-Education is a fully developed subject with the laws of growth and development, much like other subjects in the curriculum. It undergoes development through moral judgments, emotional experiences, and cultural activities that motivate learners to acquire moral strength and clarity in their thoughts and actions.

Learners learn and enrich this subject through careful nurturing and guidance provided by wise teachers and parents who embody moral principles in their actions.

Integrating Moral Values Across the Curriculum

The core content of all school courses, whether in Arts, Science, Commerce, etc., should be grounded in moral values and judgments. Learners should engage in thoughtful cultivation of key facts and figures in each subject to promote moral culture and character development.

Practical Approaches to Imparting Moral Values

Schools should incorporate both theoretical and practical approaches to impart moral values . These values can be presented to learners through stories, dramatization of lessons, sketches, drawings, festoons, and various other creative methods.

In essence, the school itself should embody the living values of social life and society as a whole.

Specifically, the values of cooperation, sympathy, dedication, and tolerance should be taught to children in the classroom and within society so that they may realize that true and genuine happiness and benefit in life can be achieved through the practice of these qualities in group living.

The Role of Teachers in Moral Education

Pedagogical applications related to components of values such as morality and ethics should have a profound psychological impact on teachers.

They should receive proper moral training because it is the teachers who must consistently and rationally cultivate moral thoughts and actions. Consequently, children will be capable of acquiring moral insight and feelings with great enthusiasm, inspired by their teachers’ character and personality.

Conclusion: Integration of Academic Excellence and Value Education

Imitating Spenser Herbert, we can safely say that Value Education encapsulates the entire purpose of education, including the inner quality, insight, and volition of children who, through the application of moral virtues in character and behavior, become citizens of good character within a nation.

Mere academic knowledge without a deep foundation in moral and spiritual values will only mold one-sided personalities. These individuals may accumulate wealth and material possessions but will remain impoverished in self-understanding, the promotion of peace, and contributions to social welfare.

To emphasize this fact, Swami Vivekananda said, ‘Excess of knowledge and power, without holiness, makes human beings devils.’

Value Education necessitates academic excellence, especially to equip learners thoroughly with its elements so that they feel confident in implementing these values in their individual and social lives. This is because academic teaching is systematic, and the impact of education is bound to be fruitfully realistic and beneficial.

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Leverage Beyond /

Importance of Value Education

- Updated on

- Jan 18, 2024

What is Value Education? Value-based education emphasizes the personality development of individuals to shape their future and tackle difficult situations with ease. It moulds the children so they get attuned to changing scenarios while handling their social, moral, and democratic duties efficiently. The importance of value education can be understood through its benefits as it develops physical and emotional aspects, teaches mannerisms and develops a sense of brotherhood, instils a spirit of patriotism as well as develops religious tolerance in students. Let’s understand the importance of value education in schools as well as its need and importance in the 21st century.

Here’s our review of the Current Education System of India !

This Blog Includes:

Need and importance of value education, purpose of value education, importance of value education in school, difference between traditional and value education, essay on importance of value education, speech on importance of value education, early age moral and value education, young college students (1st or 2nd-year undergraduates), workshops for adults, student exchange programs, co-curricular activities, how it can be taught & associated teaching methods.

This type of education should not be seen as a separate discipline but as something that should be inherent in the education system. Merely solving problems must not be the aim, the clear reason and motive behind must also be thought of. There are multiple facets to understanding the importance of value education.

Here is why there is an inherent need and importance of value education in the present world:

- It helps in making the right decisions in difficult situations and improving decision-making abilities.

- It teaches students with essential values like kindness, compassion and empathy.

- It awakens curiosity in children developing their values and interests. This further helps in skill development in students.

- It also fosters a sense of brotherhood and patriotism thus helping students become more open-minded and welcoming towards all cultures as well as religions.

- It provides a positive direction to a student’s life as they are taught about the right values and ethics.

- It helps students find their true purpose towards serving society and doing their best to become a better version of themselves.

- With age comes a wide range of responsibilities. This can at times develop a sense of meaninglessness and can lead to a rise in mental health disorders, mid-career crisis and growing discontent with one’s life. Value education aims to somewhat fill the void in people’s lives.

- Moreover, when people study the significance of values in society and their lives, they are more convinced and committed to their goals and passions. This leads to the development of awareness which results in thoughtful and fulfilling decisions.

- The key importance of value education is highlighted in distinguishing the execution of the act and the significance of its value. It instils a sense of ‘meaning’ behind what one is supposed to do and thus aids in personality development .

In the contemporary world, the importance of value education is multifold. It becomes crucial that is included in a child’s schooling journey and even after that to ensure that they imbibe moral values as well as ethics.

Here are the key purposes of value education:

- To ensure a holistic approach to a child’s personality development in terms of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual aspects

- Inculcation of patriotic spirit as well as the values of a good citizen

- Helping students understand the importance of brotherhood at social national and international levels

- Developing good manners and responsibility and cooperativeness

- Promoting the spirit of curiosity and inquisitiveness towards the orthodox norms

- Teaching students about how to make sound decisions based on moral principles

- Promoting a democratic way of thinking and living

- Imparting students with the significance of tolerance and respect towards different cultures and religious faiths

There is an essential need and importance of value education in school curriculums as it helps students learn the basic fundamental morals they need to become good citizens as well as human beings. Here are the top reasons why value education in school is important:

- Value education can play a significant role in shaping their future and helping them find their right purpose in life.

- Since school paves the foundation for every child’s learning, adding value-based education to the school curriculum can help them learn the most important values right from the start of their academic journey.

- Value education as a discipline in school can also be focused more on learning human values rather than mugging up concepts, formulas and theories for higher scores. Thus, using storytelling in value education can also help students learn the essentials of human values.

- Education would surely be incomplete if it didn’t involve the study of human values that can help every child become a kinder, compassionate and empathetic individual thus nurturing emotional intelligence in every child.

Both traditional, as well as values education, is essential for personal development. Both help us in defining our objectives in life. However, while the former teaches us about scientific, social, and humanistic knowledge, the latter helps to become good humans and citizens. Opposite to traditional education, values education does not differentiate between what happens inside and outside the classroom.

Value Education plays a quintessential role in contributing to the holistic development of children. Without embedding values in our kids, we wouldn’t be able to teach them about good morals, what is right and what is wrong as well as key traits like kindness, empathy and compassion. The need and importance of value education in the 21st century are far more important because of the presence of technology and its harmful use. By teaching children about essential human values, we can equip them with the best digital skills and help them understand the importance of ethical behaviour and cultivating compassion. It provides students with a positive view of life and motivates them to become good human beings, help those in need, respect their community as well as become more responsible and sensible.

Youngsters today move through a gruelling education system that goes on almost unendingly. Right from when parents send them to kindergarten at the tender age of 4 or 5 to completing their graduation, there is a constant barrage of information hurled at them. It is a puzzling task to make sense of this vast amount of unstructured information. On top of that, the bar to perform better than peers and meet expectations is set at a quite high level. This makes a youngster lose their curiosity and creativity under the burden. They know ‘how’ to do something but fail to answer the ‘why’. They spend their whole childhood and young age without discovering the real meaning of education. This is where the importance of value education should be established in their life. It is important in our lives because it develops physical and emotional aspects, teaches mannerisms and develops a sense of brotherhood, instils a spirit of patriotism as well as develops religious tolerance in students. Thus, it is essential to teach value-based education in schools to foster the holistic development of students. Thank you.

Importance of Value Education Slideshare PPT

Types of Value Education

To explore how value education has been incorporated at different levels from primary education, and secondary education to tertiary education, we have explained some of the key phases and types of value education that must be included to ensure the holistic development of a student.

Middle and high school curriculums worldwide including in India contain a course in moral science or value education. However, these courses rarely focus on the development and importance of values in lives but rather on teachable morals and acceptable behaviour. Incorporating some form of value education at the level of early childhood education can be constructive.

Read more at Child Development and Pedagogy

Some universities have attempted to include courses or conduct periodic workshops that teach the importance of value education. There has been an encouraging level of success in terms of students rethinking what their career goals are and increased sensitivity towards others and the environment.

Our Top Read: Higher Education in India

Alarmingly, people who have only been 4 to 5 years into their professional careers start showing signs of job exhaustion, discontent, and frustration. The importance of value education for adults has risen exponentially. Many non-governmental foundations have begun to conduct local workshops so that individuals can deal with their issues and manage such questions in a better way.

Recommended Read: Adult Education

It is yet another way of inculcating a spirit of kinship amongst students. Not only do student exchange programs help explore an array of cultures but also help in understanding the education system of countries.

Quick Read: Scholarships for Indian Students to Study Abroad

Imparting value education through co-curricular activities in school enhances the physical, mental, and disciplinary values among children. Furthermore, puppetry , music, and creative writing also aid in overall development.

Check Out: Drama and Art in Education

The concept of teaching values has been overly debated for centuries. Disagreements have taken place over whether value education should be explicitly taught because of the mountainous necessity or whether it should be implicitly incorporated into the teaching process. An important point to note is that classes or courses may not be successful in teaching values but they can teach the importance of value education. It can help students in exploring their inner passions and interests and work towards them. Teachers can assist students in explaining the nature of values and why it is crucial to work towards them. The placement of this class/course, if there is to be one, is still under fierce debate.

Value education is the process through which an individual develops abilities, attitudes, values as well as other forms of behaviour of positive values depending on the society he lives in.

Every individual needs to ensure a holistic approach to their personality development in physical, mental, social and moral aspects. It provides a positive direction to the students to shape their future, helping them become more responsible and sensible and comprehending the purpose of their lives.

Values are extremely important because they help us grow and develop and guide our beliefs, attitudes and behaviour. Our values are reflected in our decision-making and help us find our true purpose in life and become responsible and developed individuals.

The importance of value education at various stages in one’s life has increased with the running pace and complexities of life. It is becoming difficult every day for youngsters to choose their longing and pursue careers of their choice. In this demanding phase, let our Leverage Edu experts guide you in following the career path you have always wanted to explore by choosing an ideal course and taking the first step to your dream career .

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Your Article is awesome. It’s very helpful to know the value of education and the importance of value education. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Anil, Thanks for your feedback!

Value education is the most important thing because they help us grow and develop and guide our beliefs, attitudes and behaviour. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Susmita, Rightly said!

Best blog. well explained. Thank you for sharing keep sharing.

Thanks.. For.. The Education value topic.. With.. This.. Essay. I.. Scored.. Good. Mark’s.. In.. My. Exam thanks a lot..

Your Article is Very nice.It is Very helpful for me to know the value of Education and its importance…Thanks for sharing your thoughts about education…Thank you ……

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)