- Cookies & Privacy

- GETTING STARTED

- Introduction

- FUNDAMENTALS

- Acknowledgements

- Research questions & hypotheses

- Concepts, constructs & variables

- Research limitations

- Getting started

- Sampling Strategy

- Research Quality

- Research Ethics

- Data Analysis

How to structure the Sampling Strategy section of your dissertation

The Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter (usually Chapter Three: Research Strategy ) needs to be well structured. A good structure involves four steps : describing , explaining , stating and justifying . You need to: (1) describe what you are studying, including the units involved in your sample and the target population ; (2) explain the types of sampling technique available to you; (3) state and describe the sampling strategy you used; and (4) justify your choice of sampling strategy. In this article, we explain each of these four steps:

- STEP ONE: Describe what you are studying

- STEP TWO: Explain the types of sampling technique available to you

- STEP THREE: State and describe the sampling strategy you used

- STEP FOUR: Justify your choice of sampling strategy

STEP ONE Describe what you are studying

First, the reader needs to know what you studied. This should include details about the following:

The units you measured (or examined).

Your target population .

If you used a probability sampling technique to select your sample , you will also need to describe:

Your sampling frame .

If you are unsure what of any of these terms mean (i.e., unit , sampling frame , population ), you might want to read the article, Sampling: The basics , before reading on. If you feel comfortable with these terms, let's imagine we completed a dissertation on the career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England. Below we describe our units , target population and sampling frame (imagining that we used a probability sampling technique ).

Career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England We examined the career choices of all students at the University of Oxford, England. By all students we mean all undergraduate and postgraduate students, full-time and part-time, studying at the University of Oxford, England, enrolled as of 05 January 2011.

From this description , the reader learns the following:

Units: students Population: all undergraduate and postgraduate students, full-time and part-time, at the University of Oxford, England Sampling frame: all students enrolled at the University of Oxford, as of 05 January 2011 (i.e., according to Student Records, assuming this is the department that maintains a list of all students studying at the university)

Note the difference between the target population and the sampling frame, from which we select our sample (when using a probability sampling technique). They are the same in all respects apart from the fact that the sampling frame tells the reader that only those students enrolled in the university according to Student Records on a particular date (i.e., 05 January 2011) are being studied. If the list of students kept by Student Records is very different from the population of all students studying at the university, this should be made clear [see the article, Sampling: The basics, to understand more about sampling frames and potential sampling bias].

By the time you come to write up the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter, you should know whether the sampling frame is the same as the population. If it is not, you should highlight the difference between the two. This completes the first part of the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter.

STEP TWO Explain the types of sampling technique available to you

Once you know what units you are studying, as well as your population and sampling frame , the reader will often want to know what types of sampling technique you could use . We say could use rather than should use because whilst there are certain ideal choices of sampling technique, there is seldom a right or wrong answer. Instead, researchers choose sampling techniques that they feel are most appropriate to their study, based on theoretical and practical reasons.

Broadly speaking, you could choose to select your sample from (a) your sampling frame using either a probability sampling technique (e.g., simple random sampling, systematic random sampling, stratified random sampling) or (b) from your population using a non-probability sampling technique (e.g., quota sampling, purposive sampling, convenience sampling, snowball sampling). To understand the differences between these techniques, as well as their advantages and disadvantages, you may want to start by reading the articles: Probability sampling and Non-probability sampling .

When explaining the types of sampling technique that were available to you in this part of your Sampling Strategy section, you should take into account: (a) the research strategy guiding your dissertation; and (b) theoretical and practical sampling issues.

The research strategy guiding your dissertation

Theoretically , the ideal sampling technique for a piece of research (i.e., probability or non-probability sampling) differs depending on whether you are using a quantitative , qualitative or mixed methods research design .

Theoretical and practical sampling issues

Whilst there are theoretical ideals when it comes to choosing a sampling technique to use for your dissertation (i.e., probability or non-probability sampling), it is often practical issues that determine not only whether you choose one type of sampling technique over another (e.g., non-probability sampling over probability sampling ), but also the specific technique that you use (e.g., purposive sampling over quota sampling ; i.e., both are non-probability sampling techniques). Such practical issues range from whether your target population is known (i.e., whether you can get access to a list of the population) to whether you have the time and money to get access to such a list [click on the relevant article to understand the advantages and disadvantages (i.e., theoretical and practical considerations ) of the different probability sampling (e.g., simple random sampling , systematic random sampling , stratified random sampling ) and non-probability sampling techniques (e.g., quota sampling , purposive sampling , self-selection sampling , convenience sampling , snowball sampling )].

Assuming that you understand the differences between these sampling techniques, and their relative merits, let's consider what sampling choices are open to us using our example of career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England . The green text illustrates what we have already written above.

Career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England We examined the career choices of all students at the University of Oxford, England. By all students we mean all undergraduate and postgraduate students, full-time and part-time, studying at the University of Oxford, England, enrolled as of 05 January 2011. Since our research drew on a quantitative research design , the ideal would have been to use a probability sampling technique because this allows us to make statistical inferences (i.e., generalisations ) from our sample of students to all students at the university . Such a probability sampling technique would provide greater external validity for our findings. Since we wanted to compare the career choices of different strata (i.e., groups of students); more specifically, males and females , the appropriate choice of probability sampling technique would have been a stratified random sample . However, if it were not possible to use a probability sampling technique , we could have used a non-probability sampling technique . Since we wanted to compare different strata (i.e., groups of students) and achieve a sample that is as representative as possible of our population , we could have used a quota sample .

From this explanation , the reader learns the following:

Types of sampling strategy available: probability and non-probability sampling Ideal choice: probability sampling Preferred choice of probability sampling technique: stratified random sample Preferred choice of non-probability sampling technique: quota sample

When you are writing up this part of the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter, you may be expected to include a much more comprehensive list of reasons why you prefer one type of sampling strategy (i.e., probability or non-probability) and more specifically, a particular sampling technique (e.g., stratified random sampling over quota sampling). We provide information about the advantages and disadvantages of these different sampling strategies and sampling techniques in the following articles: for probability sampling , see simple random sampling , systematic random sampling , stratified random sampling ; for non-probability sampling techniques, see quota sampling , purposive sampling , self-selection sampling , convenience sampling , snowball sampling .

STEP THREE State and describe the sampling strategy you used

Third, you need to state what sampling strategy and sampling technique you used, describing what you did.

Again, let's consider this for our example of career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England . The green text illustrates what we have already written above.

Career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England We examined the career choices of all students at the University of Oxford, England. By all students we mean all undergraduate and postgraduate students, full-time and part-time, studying at the University of Oxford, England, enrolled as of 05 January 2011. Since our research drew on a quantitative research design , the ideal would have been to use a probability sampling technique because this allows us to make statistical inferences (i.e., generalisations ) from our sample of students to all students at the university. Such a probability sampling technique would provide greater external validity for our findings. Since we wanted to compare the career choices of different strata (i.e., groups of students), including males and females , the appropriate choice of probability sampling technique would have been a stratified random sample . However, if it were not possible to use a probability sampling technique , we could have used a non-probability sampling technique . Since we wanted to compare different strata (i.e., groups of students) and achieve a sample that is as representative as possible of our population , we could have used a quota sample . In the event, we used quota sampling to select the sample of students that would be invited to take part in our dissertation research. Student Records provided us with the appropriate quotas for male and female students, which showed a 53:47 male-female ration [ NOTE: this is a fictitious figure]. We selected a sample size of 200 students, which was based on subjective judgement and practicalities of cost and time. Therefore, we sampled 106 male students (i.e., 53% of our sample size of 200 students) and 94 female students (i.e., 47% of our sample size of 200 students). For convenience, we stood outside the main library where we felt the thoroughfare (i.e., number of students passing by) would be highest.

From this statement and description , the reader learns the following:

Sampling strategy chosen: non-probability sampling Specific sampling technique used: quota sampling

Details of quota sampling: strata (i.e., groups of students) of interest are males and females ratio of males-females at the university was 53:47 sample size selected was 200 students quota sample filled based on ease of access to students at the main university library.

Again, when you are writing up this part of the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter, it may be appropriate to include greater description of the sampling technique you used.

STEP FOUR Justify your choice of sampling strategy

Finally, you need to justify your choice of sampling strategy. When writing up the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter, you may find it easier to combine the third and fourth steps (i.e., stating and describing the sampling strategy you used, as well as justifying that choice). Taking our example of the career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England , we illustrate how the two steps can be integrated. As before, the green text illustrates what we have already written above.

Career choices of students at the University of Oxford, England We examined the career choices of all students at the University of Oxford, England. By all students we mean all undergraduate and postgraduate students, full-time and part-time, studying at the University of Oxford, England, enrolled as of 05 January 2011. Since our research drew on a quantitative research design , the ideal would have been to use a probability sampling technique because this allows us to make statistical inferences (i.e., generalisations ) from our sample of students to all students at the university. Such a probability sampling technique would provide greater external validity for our findings. Since we wanted to compare the career choices of different strata (i.e., groups of students), including males and females , the appropriate choice of probability sampling technique would have been a stratified random sample . However, if it were not possible to use a probability sampling technique , we could have used a non-probability sampling technique . Since we wanted to compare different strata (i.e., groups of students) and achieve a sample that is as representative as possible of our population , we could have used a quota sample . In the event, we used quota sampling to select the sample of students that would be invited to take part in our dissertation research. We were unable to use a stratified random sampling , our preferred choice, because we could not obtain permission from Student Records to access a complete list of all students at the university. Without any other way of attaining a list of all students, we had to use quota sampling . However, Student Records did provide us with the appropriate quotas for male and female students, which showed a 53:47 male-female ration [note: this is a fictitious figure]. We selected a sample size of 200 students, which was based on subjective judgement and practicalities of cost and time. Therefore, we sampled 106 male students (i.e., 53% of our sample size of 200 students) and 94 female students (i.e., 47% of our sample size of 200 students). For convenience, we stood outside the main library where we felt the thoroughfare (i.e., number of students passing by) would be highest.

From this justification , the reader learns the following:

Main reason for rejecting the ideal sampling strategy:

Access to a list of all students (i.e., the sampling frame needed for probability sampling ) was not granted by Student Records.

No other way of attaining a list of all students was available.

When you think about justifying your choice of sampling technique when writing up the Sampling Strategy section of your Research Strategy chapter, you should consider both practical reasons (e.g., what time you have available, what access you have, etc.) and theoretical reasons (i.e., those relating to the specific sampling technique , but also your choice of research paradigm , research design and research methods ).

Introduction to Research Methods

7 samples and populations.

So you’ve developed your research question, figured out how you’re going to measure whatever you want to study, and have your survey or interviews ready to go. Now all your need is other people to become your data.

You might say ‘easy!’, there’s people all around you. You have a big family tree and surely them and their friends would have happy to take your survey. And then there’s your friends and people you’re in class with. Finding people is way easier than writing the interview questions or developing the survey. That reaction might be a strawman, maybe you’ve come to the conclusion none of this is easy. For your data to be valuable, you not only have to ask the right questions, you have to ask the right people. The “right people” aren’t the best or the smartest people, the right people are driven by what your study is trying to answer and the method you’re using to answer it.

Remember way back in chapter 2 when we looked at this chart and discussed the differences between qualitative and quantitative data.

One of the biggest differences between quantitative and qualitative data was whether we wanted to be able to explain something for a lot of people (what percentage of residents in Oklahoma support legalizing marijuana?) versus explaining the reasons for those opinions (why do some people support legalizing marijuana and others not?). The underlying differences there is whether our goal is explain something about everyone, or whether we’re content to explain it about just our respondents.

‘Everyone’ is called the population . The population in research is whatever group the research is trying to answer questions about. The population could be everyone on planet Earth, everyone in the United States, everyone in rural counties of Iowa, everyone at your university, and on and on. It is simply everyone within the unit you are intending to study.

In order to study the population, we typically take a sample or a subset. A sample is simply a smaller number of people from the population that are studied, which we can use to then understand the characteristics of the population based on that subset. That’s why a poll of 1300 likely voters can be used to guess at who will win your states Governor race. It isn’t perfect, and we’ll talk about the math behind all of it in a later chapter, but for now we’ll just focus on the different types of samples you might use to study a population with a survey.

If correctly sampled, we can use the sample to generalize information we get to the population. Generalizability , which we defined earlier, means we can assume the responses of people to our study match the responses everyone would have given us. We can only do that if the sample is representative of the population, meaning that they are alike on important characteristics such as race, gender, age, education. If something makes a large difference in people’s views on a topic in your research and your sample is not balanced, you’ll get inaccurate results.

Generalizability is more of a concern with surveys than with interviews. The goal of a survey is to explain something about people beyond the sample you get responses from. You’ll never see a news headline saying that “53% of 1250 Americans that responded to a poll approve of the President”. It’s only worth asking those 1250 people if we can assume the rest of the United States feels the same way overall. With interviews though we’re looking for depth from their responses, and so we are less hopefully that the 15 people we talk to will exactly match the American population. That doesn’t mean the data we collect from interviews doesn’t have value, it just has different uses.

There are two broad types of samples, with several different techniques clustered below those. Probability sampling is associated with surveys, and non-probability sampling is often used when conducting interviews. We’ll first describe probability samples, before discussing the non-probability options.

The type of sampling you’ll use will be based on the type of research you’re intending to do. There’s no sample that’s right or wrong, they can just be more or less appropriate for the question you’re trying to answer. And if you use a less appropriate sampling strategy, the answer you get through your research is less likely to be accurate.

7.1 Types of Probability Samples

So we just hinted at the idea that depending on the sample you use, you can generalize the data you collect from the sample to the population. That will depend though on whether your sample represents the population. To ensure that your sample is representative of the population, you will want to use a probability sample. A representative sample refers to whether the characteristics (race, age, income, education, etc) of the sample are the same as the population. Probability sampling is a sampling technique in which every individual in the population has an equal chance of being selected as a subject for the research.

There are several different types of probability samples you can use, depending on the resources you have available.

Let’s start with a simple random sample . In order to use a simple random sample all you have to do is take everyone in your population, throw them in a hat (not literally, you can just throw their names in a hat), and choose the number of names you want to use for your sample. By drawing blindly, you can eliminate human bias in constructing the sample and your sample should represent the population from which it is being taken.

However, a simple random sample isn’t quite that easy to build. The biggest issue is that you have to know who everyone is in order to randomly select them. What that requires is a sampling frame , a list of all residents in the population. But we don’t always have that. There is no list of residents of New York City (or any other city). Organizations that do have such a list wont just give it away. Try to ask your university for a list and contact information of everyone at your school so you can do a survey? They wont give it to you, for privacy reasons. It’s actually harder to think of popultions you could easily develop a sample frame for than those you can’t. If you can get or build a sampling frame, the work of a simple random sample is fairly simple, but that’s the biggest challenge.

Most of the time a true sampling frame is impossible to acquire, so researcher have to settle for something approximating a complete list. Earlier generations of researchers could use the random dial method to contact a random sample of Americans, because every household had a single phone. To use it you just pick up the phone and dial random numbers. Assuming the numbers are actually random, anyone might be called. That method actually worked somewhat well, until people stopped having home phone numbers and eventually stopped answering the phone. It’s a fun mental exercise to think about how you would go about creating a sampling frame for different groups though; think through where you would look to find a list of everyone in these groups:

Plumbers Recent first-time fathers Members of gyms

The best way to get an actual sampling frame is likely to purchase one from a private company that buys data on people from all the different websites we use.

Let’s say you do have a sampling frame though. For instance, you might be hired to do a survey of members of the Republican Party in the state of Utah to understand their political priorities this year, and the organization could give you a list of their members because they’ve hired you to do the reserach. One method of constructing a simple random sample would be to assign each name on the list a number, and then produce a list of random numbers. Once you’ve matched the random numbers to the list, you’ve got your sample. See the example using the list of 20 names below

and the list of 5 random numbers.

Systematic sampling is similar to simple random sampling in that it begins with a list of the population, but instead of choosing random numbers one would select every kth name on the list. What the heck is a kth? K just refers to how far apart the names are on the list you’re selecting. So if you want to sample one-tenth of the population, you’d select every tenth name. In order to know the k for your study you need to know your sample size (say 1000) and the size of the population (75000). You can divide the size of the population by the sample (75000/1000), which will produce your k (750). As long as the list does not contain any hidden order, this sampling method is as good as the random sampling method, but its only advantage over the random sampling technique is simplicity. If we used the same list as above and wanted to survey 1/5th of the population, we’d include 4 of the names on the list. It’s important with systematic samples to randomize the starting point in the list, otherwise people with A names will be oversampled. If we started with the 3rd name, we’d select Annabelle Frye, Cristobal Padilla, Jennie Vang, and Virginia Guzman, as shown below. So in order to use a systematic sample, we need three things, the population size (denoted as N ), the sample size we want ( n ) and k , which we calculate by dividing the population by the sample).

N= 20 (Population Size) n= 4 (Sample Size) k= 5 {20/4 (kth element) selection interval}

We can also use a stratified sample , but that requires knowing more about the population than just their names. A stratified sample divides the study population into relevant subgroups, and then draws a sample from each subgroup. Stratified sampling can be used if you’re very concerned about ensuring balance in the sample or there may be a problem of underrepresentation among certain groups when responses are received. Not everyone in your sample is equally likely to answer a survey. Say for instance we’re trying to predict who will win an election in a county with three cities. In city A there are 1 million college students, in city B there are 2 million families, and in City C there are 3 million retirees. You know that retirees are more likely than busy college students or parents to respond to a poll. So you break the sample into three parts, ensuring that you get 100 responses from City A, 200 from City B, and 300 from City C, so the three cities would match the population. A stratified sample provides the researcher control over the subgroups that are included in the sample, whereas simple random sampling does not guarantee that any one type of person will be included in the final sample. A disadvantage is that it is more complex to organize and analyze the results compared to simple random sampling.

Cluster sampling is an approach that begins by sampling groups (or clusters) of population elements and then selects elements from within those groups. A researcher would use cluster sampling if getting access to elements in an entrie population is too challenging. For instance, a study on students in schools would probably benefit from randomly selecting from all students at the 36 elementary schools in a fictional city. But getting contact information for all students would be very difficult. So the researcher might work with principals at several schools and survey those students. The researcher would need to ensure that the students surveyed at the schools are similar to students throughout the entire city, and greater access and participation within each cluster may make that possible.

The image below shows how this can work, although the example is oversimplified. Say we have 12 students that are in 6 classrooms. The school is in total 1/4th green (3/12), 1/4th yellow (3/12), and half blue (6/12). By selecting the right clusters from within the school our sample can be representative of the entire school, assuming these colors are the only significant difference between the students. In the real world, you’d want to match the clusters and population based on race, gender, age, income, etc. And I should point out that this is an overly simplified example. What if 5/12s of the school was yellow and 1/12th was green, how would I get the right proportions? I couldn’t, but you’d do the best you could. You still wouldn’t want 4 yellows in the sample, you’d just try to approximiate the population characteristics as best you can.

7.2 Actually Doing a Survey

All of that probably sounds pretty complicated. Identifying your population shouldn’t be too difficult, but how would you ever get a sampling frame? And then actually identifying who to include… It’s probably a bit overwhelming and makes doing a good survey sound impossible.

Researchers using surveys aren’t superhuman though. Often times, they use a little help. Because surveys are really valuable, and because researchers rely on them pretty often, there has been substantial growth in companies that can help to get one’s survey to its intended audience.

One popular resource is Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (more commonly known as MTurk). MTurk is at its most basic a website where workers look for jobs (called hits) to be listed by employers, and choose whether to do the task or not for a set reward. MTurk has grown over the last decade to be a common source of survey participants in the social sciences, in part because hiring workers costs very little (you can get some surveys completed for penny’s). That means you can get your survey completed with a small grant ($1-2k at the low end) and get the data back in a few hours. Really, it’s a quick and easy way to run a survey.

However, the workers aren’t perfectly representative of the average American. For instance, researchers have found that MTurk respondents are younger, better educated, and earn less than the average American.

One way to get around that issue, which can be used with MTurk or any survey, is to weight the responses. Because with MTurk you’ll get fewer responses from older, less educated, and richer Americans, those responses you do give you want to count for more to make your sample more representative of the population. Oversimplified example incoming!

Imagine you’re setting up a pizza party for your class. There are 9 people in your class, 4 men and 5 women. You only got 4 responses from the men, and 3 from the women. All 4 men wanted peperoni pizza, while the 3 women want a combination. Pepperoni wins right, 4 to 3? Not if you assume that the people that didn’t respond are the same as the ones that did. If you weight the responses to match the population (the full class of 9), a combination pizza is the winner.

Because you know the population of women is 5, you can weight the 3 responses from women by 5/3 = 1.6667. If we weight (or multiply) each vote we did receive from a woman by 1.6667, each vote for a combination now equals 1.6667, meaning that the 3 votes for combination total 5. Because we received a vote from every man in the class, we just weight their votes by 1. The big assumption we have to make is that the people we didn’t hear from (the 2 women that didn’t vote) are similar to the ones we did hear from. And if we don’t get any responses from a group we don’t have anything to infer their preferences or views from.

Let’s go through a slightly more complex example, still just considering one quality about people in the class. Let’s say your class actually has 100 students, but you only received votes from 50. And, what type of pizza people voted for is mixed, but men still prefer peperoni overall, and women still prefer combination. The class is 60% female and 40% male.

We received 21 votes from women out of the 60, so we can weight their responses by 60/21 to represent the population. We got 29 votes out of the 40 for men, so their responses can be weighted by 40/29. See the math below.

53.8 votes for combination? That might seem a little odd, but weighting isn’t a perfect science. We can’t identify what a non-respondent would have said exactly, all we can do is use the responses of other similar people to make a good guess. That issue often comes up in polling, where pollsters have to guess who is going to vote in a given election in order to project who will win. And we can weight on any characteristic of a person we think will be important, alone or in combination. Modern polls weight on age, gender, voting habits, education, and more to make the results as generalizable as possible.

There’s an appendix later in this book where I walk through the actual steps of creating weights for a sample in R, if anyone actually does a survey. I intended this section to show that doing a good survey might be simpler than it seemed, but now it might sound even more difficult. A good lesson to take though is that there’s always another door to go through, another hurdle to improve your methods. Being good at research just means being constantly prepared to be given a new challenge, and being able to find another solution.

7.3 Non-Probability Sampling

Qualitative researchers’ main objective is to gain an in-depth understanding on the subject matter they are studying, rather than attempting to generalize results to the population. As such, non-probability sampling is more common because of the researchers desire to gain information not from random elements of the population, but rather from specific individuals.

Random selection is not used in nonprobability sampling. Instead, the personal judgment of the researcher determines who will be included in the sample. Typically, researchers may base their selection on availability, quotas, or other criteria. However, not all members of the population are given an equal chance to be included in the sample. This nonrandom approach results in not knowing whether the sample represents the entire population. Consequently, researchers are not able to make valid generalizations about the population.

As with probability sampling, there are several types of non-probability samples. Convenience sampling , also known as accidental or opportunity sampling, is a process of choosing a sample that is easily accessible and readily available to the researcher. Researchers tend to collect samples from convenient locations such as their place of employment, a location, school, or other close affiliation. Although this technique allows for quick and easy access to available participants, a large part of the population is excluded from the sample.

For example, researchers (particularly in psychology) often rely on research subjects that are at their universities. That is highly convenient, students are cheap to hire and readily available on campuses. However, it means the results of the study may have limited ability to predict motivations or behaviors of people that aren’t included in the sample, i.e., people outside the age of 18-22 that are going to college.

If I ask you to get find out whether people approve of the mayor or not, and tell you I want 500 people’s opinions, should you go stand in front of the local grocery store? That would be convinient, and the people coming will be random, right? Not really. If you stand outside a rural Piggly Wiggly or an urban Whole Foods, do you think you’ll see the same people? Probably not, people’s chracteristics make the more or less likely to be in those locations. This technique runs the high risk of over- or under-representation, biased results, as well as an inability to make generalizations about the larger population. As the name implies though, it is convenient.

Purposive sampling , also known as judgmental or selective sampling, refers to a method in which the researcher decides who will be selected for the sample based on who or what is relevant to the study’s purpose. The researcher must first identify a specific characteristic of the population that can best help answer the research question. Then, they can deliberately select a sample that meets that particular criterion. Typically, the sample is small with very specific experiences and perspectives. For instance, if I wanted to understand the experiences of prominent foreign-born politicians in the United States, I would purposefully build a sample of… prominent foreign-born politicians in the United States. That would exclude anyone that was born in the United States or and that wasn’t a politician, and I’d have to define what I meant by prominent. Purposive sampling is susceptible to errors in judgment by the researcher and selection bias due to a lack of random sampling, but when attempting to research small communities it can be effective.

When dealing with small and difficult to reach communities researchers sometimes use snowball samples , also known as chain referral sampling. Snowball sampling is a process in which the researcher selects an initial participant for the sample, then asks that participant to recruit or refer additional participants who have similar traits as them. The cycle continues until the needed sample size is obtained.

This technique is used when the study calls for participants who are hard to find because of a unique or rare quality or when a participant does not want to be found because they are part of a stigmatized group or behavior. Examples may include people with rare diseases, sex workers, or a child sex offenders. It would be impossible to find an accurate list of sex workers anywhere, and surveying the general population about whether that is their job will produce false responses as people will be unwilling to identify themselves. As such, a common method is to gain the trust of one individual within the community, who can then introduce you to others. It is important that the researcher builds rapport and gains trust so that participants can be comfortable contributing to the study, but that must also be balanced by mainting objectivity in the research.

Snowball sampling is a useful method for locating hard to reach populations but cannot guarantee a representative sample because each contact will be based upon your last. For instance, let’s say you’re studying illegal fight clubs in your state. Some fight clubs allow weapons in the fights, while others completely ban them; those two types of clubs never interreact because of their disagreement about whether weapons should be allowed, and there’s no overlap between them (no members in both type of club). If your initial contact is with a club that uses weapons, all of your subsequent contacts will be within that community and so you’ll never understand the differences. If you didn’t know there were two types of clubs when you started, you’ll never even know you’re only researching half of the community. As such, snowball sampling can be a necessary technique when there are no other options, but it does have limitations.

Quota Sampling is a process in which the researcher must first divide a population into mutually exclusive subgroups, similar to stratified sampling. Depending on what is relevant to the study, subgroups can be based on a known characteristic such as age, race, gender, etc. Secondly, the researcher must select a sample from each subgroup to fit their predefined quotas. Quota sampling is used for the same reason as stratified sampling, to ensure that your sample has representation of certain groups. For instance, let’s say that you’re studying sexual harassment in the workplace, and men are much more willing to discuss their experiences than women. You might choose to decide that half of your final sample will be women, and stop requesting interviews with men once you fill your quota. The core difference is that while stratified sampling chooses randomly from within the different groups, quota sampling does not. A quota sample can either be proportional or non-proportional . Proportional quota sampling refers to ensuring that the quotas in the sample match the population (if 35% of the company is female, 35% of the sample should be female). Non-proportional sampling allows you to select your own quota sizes. If you think the experiences of females with sexual harassment are more important to your research, you can include whatever percentage of females you desire.

7.4 Dangers in sampling

Now that we’ve described all the different ways that one could create a sample, we can talk more about the pitfalls of sampling. Ensuring a quality sample means asking yourself some basic questions:

- Who is in the sample?

- How were they sampled?

- Why were they sampled?

A meal is often only as good as the ingredients you use, and your data will only be as good as the sample. If you collect data from the wrong people, you’ll get the wrong answer. You’ll still get an answer, it’ll just be inaccurate. And I want to reemphasize here wrong people just refers to inappropriate for your study. If I want to study bullying in middle schools, but I only talk to people that live in a retirement home, how accurate or relevant will the information I gather be? Sure, they might have grandchildren in middle school, and they may remember their experiences. But wouldn’t my information be more relevant if I talked to students in middle school, or perhaps a mix of teachers, parents, and students? I’ll get an answer from retirees, but it wont be the one I need. The sample has to be appropriate to the research question.

Is a bigger sample always better? Not necessarily. A larger sample can be useful, but a more representative one of the population is better. That was made painfully clear when the magazine Literary Digest ran a poll to predict who would win the 1936 presidential election between Alf Landon and incumbent Franklin Roosevelt. Literary Digest had run the poll since 1916, and had been correct in predicting the outcome every time. It was the largest poll ever, and they received responses for 2.27 million people. They essentially received responses from 1 percent of the American population, while many modern polls use only 1000 responses for a much more populous country. What did they predict? They showed that Alf Landon would be the overwhelming winner, yet when the election was held Roosevelt won every state except Maine and Vermont. It was one of the most decisive victories in Presidential history.

So what went wrong for the Literary Digest? Their poll was large (gigantic!), but it wasn’t representative of likely voters. They polled their own readership, which tended to be more educated and wealthy on average, along with people on a list of those with registered automobiles and telephone users (both of which tended to be owned by the wealthy at that time). Thus, the poll largely ignored the majority of Americans, who ended up voting for Roosevelt. The Literary Digest poll is famous for being wrong, but led to significant improvements in the science of polling to avoid similar mistakes in the future. Researchers have learned a lot in the century since that mistake, even if polling and surveys still aren’t (and can’t be) perfect.

What kind of sampling strategy did Literary Digest use? Convenience, they relied on lists they had available, rather than try to ensure every American was included on their list. A representative poll of 2 million people will give you more accurate results than a representative poll of 2 thousand, but I’ll take the smaller more representative poll than a larger one that uses convenience sampling any day.

7.5 Summary

Picking the right type of sample is critical to getting an accurate answer to your reserach question. There are a lot of differnet options in how you can select the people to participate in your research, but typically only one that is both correct and possible depending on the research you’re doing. In the next chapter we’ll talk about a few other methods for conducting reseach, some that don’t include any sampling by you.

- How it works

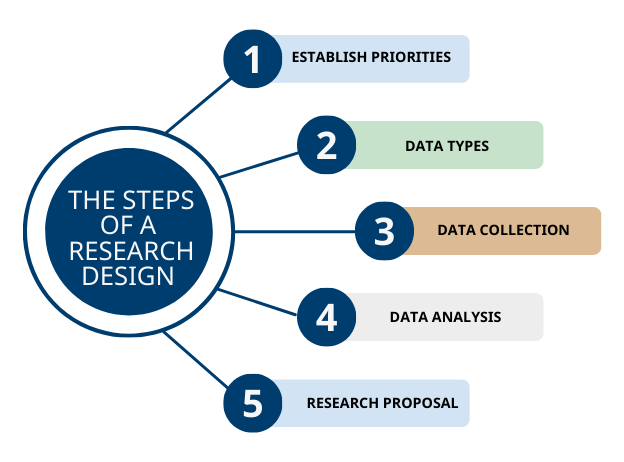

How to Write a Research Design – Guide with Examples

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On October 3, 2023

A research design is a structure that combines different components of research. It involves the use of different data collection and data analysis techniques logically to answer the research questions .

It would be best to make some decisions about addressing the research questions adequately before starting the research process, which is achieved with the help of the research design.

Below are the key aspects of the decision-making process:

- Data type required for research

- Research resources

- Participants required for research

- Hypothesis based upon research question(s)

- Data analysis methodologies

- Variables (Independent, dependent, and confounding)

- The location and timescale for conducting the data

- The time period required for research

The research design provides the strategy of investigation for your project. Furthermore, it defines the parameters and criteria to compile the data to evaluate results and conclude.

Your project’s validity depends on the data collection and interpretation techniques. A strong research design reflects a strong dissertation , scientific paper, or research proposal .

Step 1: Establish Priorities for Research Design

Before conducting any research study, you must address an important question: “how to create a research design.”

The research design depends on the researcher’s priorities and choices because every research has different priorities. For a complex research study involving multiple methods, you may choose to have more than one research design.

Multimethodology or multimethod research includes using more than one data collection method or research in a research study or set of related studies.

If one research design is weak in one area, then another research design can cover that weakness. For instance, a dissertation analyzing different situations or cases will have more than one research design.

For example:

- Experimental research involves experimental investigation and laboratory experience, but it does not accurately investigate the real world.

- Quantitative research is good for the statistical part of the project, but it may not provide an in-depth understanding of the topic .

- Also, correlational research will not provide experimental results because it is a technique that assesses the statistical relationship between two variables.

While scientific considerations are a fundamental aspect of the research design, It is equally important that the researcher think practically before deciding on its structure. Here are some questions that you should think of;

- Do you have enough time to gather data and complete the write-up?

- Will you be able to collect the necessary data by interviewing a specific person or visiting a specific location?

- Do you have in-depth knowledge about the different statistical analysis and data collection techniques to address the research questions or test the hypothesis ?

If you think that the chosen research design cannot answer the research questions properly, you can refine your research questions to gain better insight.

Step 2: Data Type you Need for Research

Decide on the type of data you need for your research. The type of data you need to collect depends on your research questions or research hypothesis. Two types of research data can be used to answer the research questions:

Primary Data Vs. Secondary Data

Qualitative vs. quantitative data.

Also, see; Research methods, design, and analysis .

Need help with a thesis chapter?

- Hire an expert from ResearchProspect today!

- Statistical analysis, research methodology, discussion of the results or conclusion – our experts can help you no matter how complex the requirements are.

Step 3: Data Collection Techniques

Once you have selected the type of research to answer your research question, you need to decide where and how to collect the data.

It is time to determine your research method to address the research problem . Research methods involve procedures, techniques, materials, and tools used for the study.

For instance, a dissertation research design includes the different resources and data collection techniques and helps establish your dissertation’s structure .

The following table shows the characteristics of the most popularly employed research methods.

Research Methods

Step 4: Procedure of Data Analysis

Use of the correct data and statistical analysis technique is necessary for the validity of your research. Therefore, you need to be certain about the data type that would best address the research problem. Choosing an appropriate analysis method is the final step for the research design. It can be split into two main categories;

Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative data analysis technique involves analyzing the numerical data with the help of different applications such as; SPSS, STATA, Excel, origin lab, etc.

This data analysis strategy tests different variables such as spectrum, frequencies, averages, and more. The research question and the hypothesis must be established to identify the variables for testing.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis of figures, themes, and words allows for flexibility and the researcher’s subjective opinions. This means that the researcher’s primary focus will be interpreting patterns, tendencies, and accounts and understanding the implications and social framework.

You should be clear about your research objectives before starting to analyze the data. For example, you should ask yourself whether you need to explain respondents’ experiences and insights or do you also need to evaluate their responses with reference to a certain social framework.

Step 5: Write your Research Proposal

The research design is an important component of a research proposal because it plans the project’s execution. You can share it with the supervisor, who would evaluate the feasibility and capacity of the results and conclusion .

Read our guidelines to write a research proposal if you have already formulated your research design. The research proposal is written in the future tense because you are writing your proposal before conducting research.

The research methodology or research design, on the other hand, is generally written in the past tense.

How to Write a Research Design – Conclusion

A research design is the plan, structure, strategy of investigation conceived to answer the research question and test the hypothesis. The dissertation research design can be classified based on the type of data and the type of analysis.

Above mentioned five steps are the answer to how to write a research design. So, follow these steps to formulate the perfect research design for your dissertation .

ResearchProspect writers have years of experience creating research designs that align with the dissertation’s aim and objectives. If you are struggling with your dissertation methodology chapter, you might want to look at our dissertation part-writing service.

Our dissertation writers can also help you with the full dissertation paper . No matter how urgent or complex your need may be, ResearchProspect can help. We also offer PhD level research paper writing services.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research design.

Research design is a systematic plan that guides the research process, outlining the methodology and procedures for collecting and analysing data. It determines the structure of the study, ensuring the research question is answered effectively, reliably, and validly. It serves as the blueprint for the entire research project.

How to write a research design?

To write a research design, define your research question, identify the research method (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed), choose data collection techniques (e.g., surveys, interviews), determine the sample size and sampling method, outline data analysis procedures, and highlight potential limitations and ethical considerations for the study.

How to write the design section of a research paper?

In the design section of a research paper, describe the research methodology chosen and justify its selection. Outline the data collection methods, participants or samples, instruments used, and procedures followed. Detail any experimental controls, if applicable. Ensure clarity and precision to enable replication of the study by other researchers.

How to write a research design in methodology?

To write a research design in methodology, clearly outline the research strategy (e.g., experimental, survey, case study). Describe the sampling technique, participants, and data collection methods. Detail the procedures for data collection and analysis. Justify choices by linking them to research objectives, addressing reliability and validity.

You May Also Like

Make sure that your selected topic is intriguing, manageable, and relevant. Here are some guidelines to help understand how to find a good dissertation topic.

To help students organise their dissertation proposal paper correctly, we have put together detailed guidelines on how to structure a dissertation proposal.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Research Methodology Example

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Methodology Chapter Template

If you’re working on a dissertation or thesis and are looking for an example of a research methodology chapter , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through a research methodology from a dissertation that earned full distinction , step by step. We start off by discussing the core components of a research methodology by unpacking our free methodology chapter template . We then progress to the sample research methodology to show how these concepts are applied in an actual dissertation, thesis or research project.

If you’re currently working on your research methodology chapter, you may also find the following resources useful:

- Research methodology 101 : an introductory video discussing what a methodology is and the role it plays within a dissertation

- Research design 101 : an overview of the most common research designs for both qualitative and quantitative studies

- Variables 101 : an introductory video covering the different types of variables that exist within research.

- Sampling 101 : an overview of the main sampling methods

- Methodology tips : a video discussion covering various tips to help you write a high-quality methodology chapter

- Private coaching : Get hands-on help with your research methodology

PS – If you’re working on a dissertation, be sure to also check out our collection of dissertation and thesis examples here .

FAQ: Research Methodology Example

Research methodology example: frequently asked questions, is the sample research methodology real.

Yes. The chapter example is an extract from a Master’s-level dissertation for an MBA program. A few minor edits have been made to protect the privacy of the sponsoring organisation, but these have no material impact on the research methodology.

Can I replicate this methodology for my dissertation?

As we discuss in the video, every research methodology will be different, depending on the research aims, objectives and research questions. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your literature review to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a research methodology chapter here .

Where can I find more examples of research methodologies?

The best place to find more examples of methodology chapters would be within dissertation/thesis databases. These databases include dissertations, theses and research projects that have successfully passed the assessment criteria for the respective university, meaning that you have at least some sort of quality assurance.

The Open Access Thesis Database (OATD) is a good starting point.

How do I get the research methodology chapter template?

You can access our free methodology chapter template here .

Is the methodology template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the template and you are free to use it as you wish.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Malays J Med Sci

- v.28(2); 2021 Apr

A Step-by-Step Process on Sample Size Determination for Medical Research

Determination of a minimum sample size required for a study is a major consideration which all researchers are confronted with at the early stage of developing a research protocol. This is because the researcher will need to have a sound prerequisite knowledge of inferential statistics in order to enable him/her to acquire a thorough understanding of the overall concept of a minimum sample size requirement and its estimation. Besides type I error and power of the study, some estimates for effect sizes will also need to be determined in the process to calculate or estimate the sample size. The appropriateness in calculating or estimating the sample size will enable the researchers to better plan their study especially pertaining to recruitment of subjects. To facilitate a researcher in estimating the appropriate sample size for their study, this article provides some recommendations for researchers on how to determine the appropriate sample size for their studies. In addition, several issues related to sample size determination were also discussed.

Introduction

Sample size calculation or estimation is an important consideration which necessitate all researchers to pay close attention to when planning a study, which has also become a compulsory consideration for all experimental studies ( 1 ). Moreover, nowadays, the selection of an appropriate sample size is also drawing much attention from researchers who are involved in observational studies when they are developing research proposals as this is now one of the factors that provides a valid justification for the application of a research grant ( 2 ). Sample size must be estimated before a study is conducted because the number of subjects to be recruited for a study will definitely have a bearing on the availability of vital resources such as manpower, time and financial allocation for the study. Nevertheless, a thorough understanding of the need to estimate or calculate an appropriate sample size for a study is crucial for a researcher to appreciate the effort expended in it.

Ideally, one can determine the parameter of a variable from a population through a census study. A census study recruits each and every subject in a population and an analysis is conducted to determine the parameter or in other words, the true value of a specific variable will be calculated in a targeted population. This approach of analysis is known as descriptive analysis. On the other hand, the estimate that is derived from a sample study is termed as a ‘statistic’ because it analyses sample data and subsequently makes inferences and conclusions from the results. This approach of analysis is known as inferential analysis, which is also the most preferred approach in research because drawing a conclusion from the sample data is much easier than performing a census study, due to various constraints especially in terms of cost, time and manpower.

In a census study, the accuracy of the parameters cannot be disputed because the parameters are derived from all subjects in the population. However, when statistics are derived from a sample, it is possible for readers to query to what extent these statistics are representative of the true values in the population. Thus, researchers will need to provide an additional piece of evidence besides the statistics, which is the P -value. The statistical significance or usually termed as ‘ P -value less than 0.05’, and it shall stand as an evidence or justification that the statistics derived from the sample can be inferred to the larger population. Some scholars may argue over the utility and versatility of P -value but it is nevertheless still applicable and acceptable until now ( 3 – 5 ).

Why It is Necessary to Perform a Sample Size Calculation or Estimation?

In order for the analysis to be conducted for addressing a specific objective of a study to be able to generate a statistically-significant result, a particular study must be conducted using a sufficiently large sample size that can detect the target effect sizes with an acceptable margin of error. In brief, a sample size is determined by three elements: i) type I error (alpha); ii) power of the study (1-type II error) and iii) effect size. A proper understanding of the concept of type I error and type II error will require a lengthy discussion. The prerequisite knowledge of statistical inference, probability and distribution function is also required to understand the overall concept ( 6 – 7 ). However, in sample size calculation, the values of both type I and type II errors are usually fixed. Type I error is usually fixed at 0.05 and sometimes 0.01 or 0.10, depending on the researcher. Meanwhile, power is usually set at 80% or 90% indicating 20% or 10% type II error, respectively. Hence, the only one factor that remains unspecified in the calculation of a sample size is the effect size of a study.

Effect size measures the ‘magnitude of effect’ of a test and it is independent of influences by the sample size ( 8 ). In other words, effect size measures the real effect of a test irrespective of its sample size. With reference to statistical tests, it is an expected parameter of a particular association (or correlation or relationship) with other tests in a targeted population. In a real setting, the parameter of a variable in a targeted population is usually unknown and therefore a study will be conducted to test and confirm these effect sizes. However, for the purpose of sample size calculation, it is still necessary to estimate the target effect sizes. By the same token, Cohen ( 9 ) presented in his article that a larger sample size is necessary to estimate small effect sizes and vice versa.