The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity – Essay Example

Introduction, what is the digital divide, causes of the digital divide, reducing the divide, digital divide: essay conclusion, works cited.

The invention of the computer and the subsequent birth of the internet have been seen as the most significant advances of the 20th century.

Over the course of the past few decades, there has been a remarkable rise in the use of computers and the internet. Sahay asserts that the ability of computing technologies to traverse geographical and social barriers has resulted in the creation of a closer knit global community (36). In addition to this, the unprecedented high adoption rate of the internet has resulted in it being a necessity in the running of our day to day lives.

However, there have been concerns due to the fact that these life transforming technologies are disparately available to people in the society. People in the high-income bracket have been seen to have a higher access to computer and the internet. This paper argues that the digital divide does exist and sets out to provide a better understanding of the causes of the same. Solutions to this problem are also addressed by this paper.

The term divide is mostly used to refer to the economic gap that exists between the poor and richer members of the society. In relation to technology, the OECD defines digital divide as ” the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard both to their opportunities to access information and communication technologies (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities.” (5). As such, the digital divide refers to the disparities in access of communication technology experienced by people.

While the respective costs of computers and internet access have reduced drastically over the years, these costs still remain significantly expensive for some people in the population. As a result of this, household income is still a large determinant of whether internet access is available at a home.

Income is especially a large factor in developing countries where most people still find the cost of owning a PC prohibitive. However, income as a factor leading to the digital divide is not only confined to developing nations. A report by the NTIA indicated that across the United States, internet access in homes continued to be closely correlated with the income levels (3).

Education also plays a key role in the digital divide. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration indicates that in America, certain groups such as Whites and Asian Americans who possess higher educational levels have higher levels of both computer ownership as well as access to the internet (3). This is because the more educated members of the society are having a higher rate of increased access to computers and internet access as opposed to the less educated.

A simple increase in the access to computer hardware resources through the production of low cost versions of information technology which is affordable to many does not necessarily result in a reduction in the digital divide. This is because in addition to the economic realities there are other prominent factors.

The lack of technological knowhow has been cited as further widening the digital divide. This means that even with access to technology, people might still be unable to make effective usage of the same. Sahay best expresses this problem by asserting that “just by providing people with computers and internet access, we cannot hope to devise a solution to bridge the digital divide.” (37).

Another cause of the digital divide is the social and cultural differences evident in most nations in the world. One’s race and culture have been known to have a deep effect on their adoption and use of a particular technology (Chen and Wellman 42).

This is an opinion which is shared by Sahay who notes that people with fears, assumptions or pre-conceived notions about technology may shy away from its usage (46). As such, people can have the economic means and access to computers and the internet but their culture may retard their use of the same.

The digital divide leads to a loss of the opportunity by many people to benefit from the tremendous economic and educational opportunities that the digital economy provides (NTIA 3). As such, the reduction of this divide by use of digital inclusion steps is necessary for everyone to share in the opportunities provided. As has been demonstrated above, one of the primary causes of the digital divide is the income inequality between people and nations.

Most developing countries have low income levels and their population cannot afford computers. To help alleviate this, programs have been put in place to reduce the cost of computers or even offer them for free to the developing countries. For example, a project by Quanta Computer Inc in 2007 set out to supply laptops to developing world children by having consumers in the U.S. buy 2 laptops and have one donated to Africa (Associated Press).

Studies indicate that males are more likely than females in the comparable population to have internet access at home mostly since women dismiss private computer and internet usage (Korupp and Szydlik 417). The bridging of this gender divide will therefore lead to a reduction in the digital divide that exists.

In recent years, there has been evidence that the gender divide is slowly closing up. This is mostly as a result of the younger generation who use the computer and internet indiscriminately therefore reducing the strong gender bias that once existed. This trend should be encouraged so as to further accelerate the bridging of the digital divide.

As has been illustrated in this paper, there exist non economic factors that may lead to people not making use of computers hence increasing the digital divide. These factors have mostly been dismissed as more attention is placed on the income related divide. However, dealing with this social and cultural related divides will also lead to a decrease in the divide. By alleviating the fears and false notions that people may have about technology, people will be more willing to use computers and the internet.

A divide, be it digital or economic acts as a major roadblock in the way for economic and social prosperity. This paper set out to investigate the digital divide phenomena. To this end, the paper has articulated the issue of digital divide, its causes and solutions to the problem.

While some people do suggest that the digital divide will get bridged on its own as time progresses, I believe that governments should take up affirmative action and fund projects that will result in a digitally inclusive society. Bridging of the digital divide will lead to people and nations increasingly being included in knowledge based societies and economies. This will have a positive impact to every community in the entire world.

Associated Press. Hundred-Dollar Laptop’ on Sale in Two-for-One Deal. 2007. Web.

Chen, Wenhong and Wellman, Barry. The Global Digital Divide- Within and Between Countries . IT & SOCIETY, VOLUME 1, ISSUE 7. 2004, PP. 39-45.

Korupp, Sylvia and Szydlik, Marc. Causes and Trends of the Digital Divide. European Sociological Review Vol. 21. no. 4, 2005.

National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). Falling Through the Net: Towards Digital Inclusion . 2000. Web.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Understanding the Digital Divide . 2001. Web.

Sahay, Rishika. The causes and Trends of the Digital Divide . 2005. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 30). The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/

"The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." IvyPanda , 30 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example'. 30 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Digital Divide Essay: the Challenge of Technology and Equity - Essay Example." October 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-digital-divide/.

- Bridging the Gap in Meeting Customer Expectations

- Artificial Intelligence: Bridging the Gap to Human-Level Intelligence

- Bridging Uncertainty in Management Consulting

- Excess Use of Technology and Motor Development

- People Have Become Overly Dependent on Technology

- Technology and Negative Effects

- The Concept and Effects of Evolution of Electronic Health Record System Software

- Americans and Digital Knowledge

- Purdue University

- Purdue Engagement

- Community Development

The State of the Digital Divide in the United States

August 17, 2022

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic shed a bright light on an issue that has been around for decades: the digital divide. As parents, children, and workers scrambled to learn, socialize, and work from home, adequate internet connectivity became critical. This analysis takes a detailed look at the digital divide as it was in 2020 (latest year available), who it affected, and its socioeconomic implications by using an innovative metric called the digital divide index . It should also increase awareness on this issue as communities and residents prepare to take advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime investment in both broadband infrastructure and digital equity, components of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Data for this analysis came primarily from the U.S. Census Bureau 5-year American Community Survey. Additional sources include but are not limited to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Lightcast (formerly known as Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. or EMSI) and Venture Forward by GoDaddy. The unit of analysis was U.S. counties for which DDI scores were calculated 1 .

Digital Divide Index

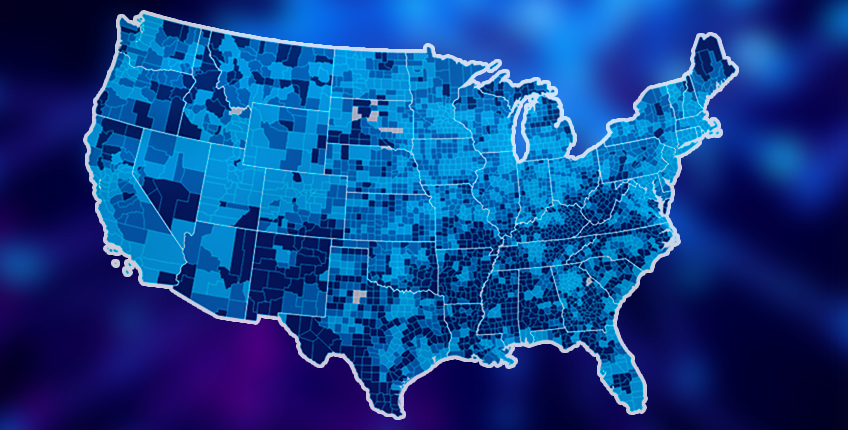

The digital divide index (DDI) consists of three scores ranging from 0 (lowest divide) to 100 (highest divide) and includes ten variables grouped in two categories: infrastructure/adoption and socioeconomic. For purposes of analysis, the overall DDI score was utilized. Counties were divided into three roughly equal groups based on the DDI score: low (1,031 counties), moderate (1,031 counties), and high (1,063 counties).

These groups were then utilized to analyze a host of other variables to better understand this issue. Figure 1 shows a map of U.S. counties by DDI groups. Of the 1,031 counties with a low digital divide, 747 or 72% were considered urban (population living in urban areas 2 was more than 50%). On the other hand, of the 1,063 counties with a high digital divide, only 187 or 17.5% were urban.

Figure 1 – U.S. Counties by DDI Group

Figure 2 shows the average DDI scores by group. The low group had an average score of 17.33, the moderate group an average score of 26.35, and the high digital divide group an average score of 36.58.

Figure 2 – Average DDI Scores by Group

Next, we look at a host of variables by the DDI group to better understand who it affected and its socioeconomic implications.

Demographics

Figure 3 shows selected demographic characteristics in counties with a low and high digital divide. A higher share of the population in counties with a high digital divide are rural, veterans, living in poverty, and disabled. On the other hand, a higher share of the population in counties with a low digital divide are minorities. While this was somewhat surprising, keep in mind that many counties with a low digital divide are urban, which in turn have a higher share of minorities. Please note that minorities include all but White, non-Hispanic. The share of children is roughly the same between low and high digital divide counties at roughly one-fifth.

Figure 3 – Percent of Population by Selected Demographic Characteristics in Low and High DDI Counties

As the economy continues to digitize, it is important to understand who is being left behind from a workforce perspective. Figure 4 shows the share of population by selected workforce-related variables in low and high digital divide counties. As shown, the share of children enrolled in K-12th grade without a computer or internet subscription is higher in counties with a high digital divide. In fact, one-quarter of children enrolled in Pre-K through 4th grade in high digital divide counties did not have a computer or internet subscription.

Regarding educational attainment, the share of those 25 years or older in high digital divide counties with a bachelor’s degree or higher is 20 percentage points lower compared to the share in low digital divide counties (16.6 versus 36.7). Likewise, the labor force participation rate among the working age population (ages 16 to 64) as well as the prime working age population (ages 25 to 54) is lower in counties with a high digital divide compared to counties with a low digital divide.

Figure 4 – Percent of Population by Selected Workforce Variables in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

Additional household characteristics need to be understood within the digital divide context. Figure 5 shows the share of households by selected characteristics in low and high digital divide counties. The share of lower earning households was higher in high digital divide counties as was the share of households with a person 60 years or older. The share of households with a person 65 or older living alone was also higher compared to low digital divide counties. Regarding the share of households with limited English, the share was slightly higher in counties with a low digital divide compared to a high digital divide.

Figure 5 – Percent of Population by Selected Workforce Variables in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

Digital distress and internet income ratio.

A related metric our Center developed is called “digital distress”. This metric utilizes fewer variables than the DDI but also offers insights for community leaders and residents regarding digital inequities. Figure 6 shows the four variables used to calculate digital distress by low and high digital distress in counties.

Figure 6 – Percent of Households by Digital Distress Metrics in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

One of the variables recently added to the DDI is the “Internet Income Ratio” or IIR. The IIR gauges digital inequality by dividing the share of homes making less than $35,000 without internet access by the share of homes making $75,000 or more without internet access. A higher IIR denotes a higher inequality. Figure 7 shows the share of homes without internet access as well as the IIR in low and high digital divide counties.

In other words, the share of lower income households without internet access is 7.1 times higher compared to the share of wealthier households without internet access in low digital divide counties. This number is higher compared to the 4.4 in counties with a high digital divide. This may seem counterintuitive but nonetheless makes the argument that digital inequity continues to be an issue even in counties with a low digital divide.

Figure 7 – Internet Income Ratio (IIR) in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

Homework and senior gap.

The homework gap has been discussed widely during the pandemic. It refers to the percentage of children that do not have internet access and struggle to complete their homework assignments. Another gap—that is not discussed as much—is the senior gap. This refers to the population aged 65 or older with no internet or computer access. This group can enhance their quality of life significantly if they can participate in online activities. Figure 8 shows the percentage of children and the population ages 65 or older with no access to computers as well as having access to computers but no internet.

As shown, counties with a high digital divide—as measured by the DDI—have a higher children (homework) and senior gap. However, it is important to note that while lack of internet is an issue among seniors, lack of computers is more of an issue. Consider that one-quarter of the population age 65 or older in high digital divide counties did not have a computer compared to 10.5% having a computer, but no internet access.

Figure 8 – Percent of Children and Seniors by Selected Characteristics in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

Digital economy.

This last group of variables shed light on the digital divide and digital economy implications. Figure 9 shows the share of jobs by selected characteristics in low and high digital divide counties. Note that the number of jobs in counties with a low digital divide grew by 11.7% between 2010 and 2020 compared to a 0.5% decrease in counties with a high digital divide. As expected, the share of digital economy jobs 3 in counties with a low digital divide was higher compared to the share in counties with a high digital divide, as was the share of remote work friendly occupations and workers ages 16 and older working from home.

Figure 9 – Share of Jobs by Selected Characteristics in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

Regarding the roughly 80% of occupations, whose digital skill levels were measured, Figure 10 shows that counties with a high digital divide had a lower share of occupations requiring high digital skills (21%) compared to counties with a low digital divide (30.8%). Likewise, the share of jobs requiring low digital skills was larger in counties with a high digital divide compared to counties with a low digital divide.

Figure 10 – Share of Occupations by Digital Skill Level in Low and High Digital Divide Counties

To wrap-up this analysis, we look at two innovative metrics developed by the Venture Forward project by GoDaddy . This project has calculated a microbusiness density metric (the higher the number, the better) that is highly correlated with economic benefits as well as the microbusiness activity index, that considers three components. Infrastructure refers to how ready the county is in terms of physical and intellectual infrastructure. The participation component looks at the number of GoDaddy online microbusinesses run by residents in the community. And the third engagement component looks at how active the websites are in the community. These new metrics are very insightful because there were 2.8 million more online microbusinesses in 2020 compared to 2019.

As shown in Figure 11, the average microbusiness density in low digital divide counties was double the density in high digital divide counties (6.4 versus 3.2). In addition, microbusiness activity index was 15 points higher in low digital divide counties (106.3 versus 91.6). What is interesting, however, is that the difference in the infrastructure and participation components is not as high. This implies that high digital divide counties have some elements in place to take advantage of the digital economy. The issue seems to be more about sophisticated online presence (engagement).

Figure 11 – Microbusiness Density and Activity Index in Low & High Digital Divide Counties

Conclusions and discussion.

The objective of this analysis is to provide a deeper understanding of who the digital divide affects and what socioeconomic implications there are to help communities as they plan and implement their digital equity and broadband infrastructure plans. Please note that we deliberately included metrics that shed light on specific populations targeted by the digital equity act. A couple of disclaimers first, before we jump into conclusions.

First, a tradeoff of grouping counties and analyzing averages is that critical and underlying dynamics are overlooked. Even if your county is included in the low digital divide category, this does not mean that the issue has been addressed. On the other hand, if your county has a high digital divide, this does not mean the situation is dire. There are certainly assets and resources that can be mobilized. Second, this data is two years old. The urgency and nature of the pandemic caused things to go in overdrive creating a highly dynamic landscape. We encourage our readers to use this as a baseline and pursue their own strategies to gather more timely and granular data, including assets and resources.

As shown in this analysis, the digital divide affects groups and areas in different ways. While a greater share of residents living in high digital divide counties are rural, this issue affects urban areas as well. An example of this is the fact that the share of minorities living in high digital divide counties was lower than those living in low digital divide areas. In other words, the share of White non-Hispanics was higher in high digital divide counties. This finding is surprising but makes the point that this issue is affecting residents across all races/ethnicities.

Poorer, disabled, older, less educated populations, and lower labor force participation rates are seen in higher digital divide counties. It is not clear from the analysis if this is a result of the digital divide or simply that these characteristics were already in place and the digital divide is just one more wrinkle to iron out. Also note that lack of devices, and not necessarily internet access, is a larger issue among the population ages 65 or older (also known as the senior gap).

The digital divide is holding back counties from participating fully in the digital economy. Again, it is not clear if this would have been the case regardless of the digital divide, but nonetheless it is placing communities at a disadvantage. As shown, counties with a high digital divide lost jobs between 2010 and 2020 while counties with a low digital divide saw an 11 percent increase. Likewise, the share of occupations requiring high digital skills was larger in counties with a low digital divide. Lastly, microbusiness density and activity were also lower in counties with a high digital divide. However, regarding microbusiness activity, the issue seems to be more about sophisticated online presence rather than infrastructure and number of businesses online.

Granted, these findings may be affected more by external, well-known urban and rural trends given that many counties with a low digital divide are urban. However, should this continue to be the case? What would happen if rural areas and other disadvantaged groups were at digital parity with their urban and more advantaged counterparts? Could they benefit from the digital economy as well? Luckily, significant investments will be taking place in the next several years to begin tackling these digital inequities with real-life consequences.

- Due to data availability, the DDI was calculated for 3,125 counties of the 3,143 in total (18 were excluded).

- Since the official 2020 urban/rural definitions will be released until December of 2022, we used one of the metrics being considered. This metric considers any Census block urban if it has at least 425 housing units per square mile, the equivalent to 1,105 people. The prior urban definition used 500 people per square mile. Please note this estimate is preliminary as the official definitions have not been released.

- Includes 44 industries with 6-digit NAICS codes considered to be “fully” part of the digital economy. These are mostly semiconductors, service providers, batteries as well as software developers and data processing to name a few. Does not include warehousing or retail associated with e-commerce.

Roberto Gallardo is the Vice President for Engagement, Director of the Purdue Center for Regional Development and an Associate Professor in the Agricultural Economics Department.... read more

Industry Clusters and Spatial Machine Learning Methods

Kumar Named New Director of the Purdue

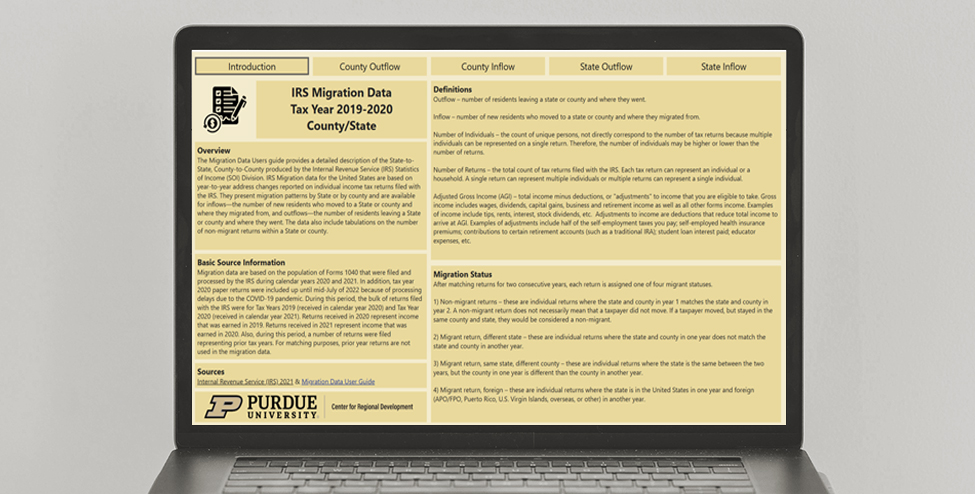

Introducing the New IRS Migration Tool

The Rural Urban Continuum Code: What Changed?

- Broadband (24)

- Data Explorations and Insights (2)

- Data Tools (12)

- Digital Inclusion (7)

- Economic and Business Development (7)

- Engagement (2)

- Health Data (3)

- Indiana's Digital Equity Landscape (5)

- Remote Work (3)

- Strategies (2)

- Workforce & Talent Development (3)

- AHA Communities

- Buy AHA Merchandise

- Cookies and Privacy Policy

In This Section

- Bridging the Digital Divide

- Project Summary

- Note to Instructors

- Photoanalysis of a Family Photograph

- Finding the Historical Context for the Family Photograph

- Sephardic Jews and Their History

- The Ladino Language

- Sara's Story

- Jacob's Story

- Morris's Story

- Clara's Story

- Photoanalysis of the Marriage Photograph

- How This Family History Project Has Been Researched

- Connections to World History

Bridging the Digital Divide: Reflective Essay on "Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age"

Introduction.

During the past decade there has been considerable discussion about the "digital divide," the widening gap between the technological "haves" and "have nots" in the US and globally. 1 Many have predicted that this gap will become ever wider over the next decades, and that significant numbers of poor peoples and nations will be left behind in the revolution in information technology that is sweeping the globe. It is indeed disquieting to think that the global technological transformation now occurring will only serve to intensify disparities and inequities among peoples, however, my observations of this project in relation to recent trends, I am optimistic that over time, the "digital divide" in the US will be narrowed, and that most sectors of society, domestically and globally, will partake of the new technologies and utilize them towards their ends. While digital divide issues have played a role in the experiences of the Southern California cluster in this project, I believe that the conditions that created them are rapidly changing and that the spread of new technologies will shortly lead to an outburst of creative development in higher education, and possibly towards the emergence of a new paradigm in teaching and learning.

Historians and The Digital Divide

My role in "Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age" as Southern California cluster leader has largely been that of coordinating the efforts of six historians to develop web-based teaching materials for the world history survey course, and to identify and work with a small group of historians to review and "field test" those materials. Our objective has been to see ways in which web-based materials can facilitate the use of active learning strategies using primary sources in the survey course, so that history survey courses can also be used to enhance the teaching of critical thinking skills in the general education curriculum. Through all, our objective has nurture a small "learning community" of historians who span the gap between two and four year institutions and who engage in constructive dialogue on the nature of the project and the teaching and learning issues it embodies. Although "digital divide" issues have played a role in the unfolding of the project during the past two or more years, these will cease to be as critical as the new educational technologies become more commonplace, easy to use, and as more computer-literate persons enter the historical profession in years to come. When the technologies become more familiar, we will be able to reflect on the teaching and learning issues with greater assurance than we are at present.

Many history faculty express some reluctance to incorporate Internet-based assignments into their classes because of the problem of access. On my campus, for example, a recent survey indicated that 30% of our students do not have Internet access at home. Thus, if we assign our students web-based materials, many will have to work on the project at one of the computer labs on campus. Additionally, some colleges have very limited student computer facilities, further complicating the problem of access. As many students are juggling their education with work and family obligations, problems of access are sometimes viewed as a hardship. Many instructors have worried about this problem. Are we discriminating against our students if we mandate that they complete computer and Internet-driven assignments? At the same time, we know that to be competitive and functional in their world, they must be computer literate. Paradoxically, are we discriminating against them if we do not require them to do computer-based assignments.

Although this has been the first question raised by faculty with respect to this project and hence has become the de facto framework guiding discussion, I believe there is often a deeper reluctance at work. The fact is that many faculty members in history and other fields in the humanities are only minimally computer literate (simple word processing and, increasingly, email). In my small History department, which consists of eight tenured or tenure track faculty and a cadre of approximately 4-6 part-time instructors, three of the eight full-timers do not have Internet access from their home office computers and are only now getting office computers that will enable easy Internet access.

Moreover, and more to the point, most of my colleagues believe that the Internet has little to offer them as a research tool, as either they work with textual materials not presently available on the Web or they specialize in types of research (e.g., close reading of texts) that makes the Web irrelevant. They have little incentive to explore the use of the new technology in their teaching, nor any particular interest in the use of technology for its own sake. It is a hard sell to convince them that they should try something new and technologically different from what has been tried and true both in their classes and in their experience as professional historians.

Thus if my department is not atypical, although the reluctance of history faculty to explore the new teaching technologies may be framed in terms of concern for students, the "culture" of the historical profession is an equally significant or even greater factor. In a subtle way, I believe these factors have also emerged in the work of our core group. Completing our projects has required far more computer literacy than we had anticipated, and for a majority of the core faculty, the technological dimension was the most challenging aspect of the project.

While at present use of the Internet is largely "transparent," i.e., easy to access and user friendly, at this time in the history of the technology, construction of web-based sites is not so transparent, although it is becoming easier all the time. That is to say, construction of web-based lessons requires much more than minimal computer literacy, as well as use of fairly expensive equipment such as fast and large computers, scanners, digital cameras, etc. While many people in the US do have such equipment for their personal use, the struggling academics I have worked with by and large do not, nor do they have lots of disposable income with which to purchase them. This equipment has not yet become part of their repertory of home consumer products the way that television sets and other appliances are, for example.

For most of the Southern California core faculty in this AHA project, the technology has been the most daunting aspect of our charge. Except for Nancy Fitch of CSU Fullerton, who easily was the most advanced among us in terms of her experience with the technology of developing web-based materials, the others were inexperienced and had varying degrees of understanding of the enterprise as a whole. Again, most of us had little or no experience engaging in our own research using the Web and no experience at all in using computer-based technologies in our teaching. Although Professor Jan Reiff of UCLA helped to orient us to the issues implicit in the project, most of us have had to learn by doing-evidence for the constructivist learning model?

For most of us, technical support from our institutions ranged from non-existent (Bill Jones at Mount SAC and Tom Reins at Fullerton College) to partial (Dave Smith at CSU Pomona and Lael Sorenson at CSU Los Angeles). For myself, I relied upon a colleague who teaches computer-based instruction courses at my university. Without Nancy Fitch's personal one-on-one assistance to several core faculty, we all would have had a far more difficult time. Thus our institutions reflected the digital divide in American higher education--between two and four year institutions and between teaching institutions and research-focused institutions--in terms of computing capability and especially in terms of technical support. In this respect, the participants in this project have been on the other (wrong) side of the digital divide during the time the project was underway.

Problems in the History Survey

As our charge in this AHA project was to focus on the role of new educational technologies in the teaching of the world history survey course, it is of interest to see ways that the core faculty considered the use of technology to address the problems inherent in the teaching of the survey course. These problems are: 1) the problem of student motivation; 2) the problem of "coverage" and, 3) the problem of integration of skill development with content delivery. 2 Although these problems are interrelated, we will consider them separately here.

With regard to student motivation, the survey course is primarily designed as a venue for students to learn basic historical information as well as basic historical concepts. The former often consists inevitably and unavoidably in the retention of historical facts, such as names of historically important people and dates of historically important events, while the historical concepts are most commonly comprised of notions such as chronological thinking or cause/effect sequences. It is probably fair to say that in our assignments and exams for the survey courses, retention of factual information is emphasized at least equally as understanding of basic historical concepts, and probably more so.

We have a basic contradiction with regard to history survey courses, in that we focus on historical facts but we are reasonably certain, based on anecdotal evidence that students offer, that the majority of these historical facts will not be retained in the students' memories for very long after the class has ended. We must teach our students the historical facts if the students are to achieve any of the other skills and insights associated with historical knowledge. In particular, analysis of documentary materials, interpretation of historical events, and construction of historical narratives all require knowledge of the basic historical facts, and the survey course is where this knowledge, precursor to higher forms of historical understanding, is introduced at the college level.

Yet we know that many students find the memorization of names and dates to be onerous and boring. How many of us have heard from students that they "hated" history in high school because "all we did" was memorize names and dates? A student will likely be turned off to the joys of historical investigation because the names and dates that have to be learned have little or no intrinsic meaning.

By and large, our core faculty did not directly address a technology-based solution to this problem, although it was an implicit element in their projects. A technology-neutral approach to the problem of motivation of students in survey courses generally focuses on three types of classroom assignments or activities: 1) those that personalize history through examples; 2) those that study a certain number of events or topics in-depth ("post-holing"); and, 3) those that emphasize active learning, or "doing history" through investigation of primary sources.

The first solution, personalizing history, is often attempted through lectures and readings about persons who lived in the past, but can also be linked to autobiographical or family history assignments. The second solution, in-depth focus, is usually modeled in lectures and then accomplished through assignment of a term paper based on secondary sources, or through a series of shorter writing assignments based on additional reading of secondary sources. The third, active learning through historical investigation based on primary sources, is less frequently employed in the survey courses but often provides the basis for discussion sections or full classroom sessions devoted to discussion of primary sources from readers that often are companions to world history textbooks.

All of the web-based projects developed by the Southern California core faculty can be used to implement one or more of the solutions to the problem of motivation. All of the projects use primary sources in conjunction with discussion questions developed by the lesson designer (active learning through primary sources); all lend themselves to production of one or more specialized writing assignments (post-holing); and at least two (Fitch and Pomerantz) provide the basis for biography and family history projects (personalizing history).

However, in general the core faculty themselves did not overtly address the issue of the role of technology in dealing with student motivation. As a rule, each instructor develops and refines solutions on a dynamic, on-going basis through the process of teaching, and generally these solutions are achieved by relying more on in-class discussions, either whole class or in small group format, and through refining the selection of assigned materials. These solutions have been made, for the most part, without having thought about technology as an aspect to the solution of a teaching and learning problem, and most of the core faculty simply reproduced the structure for in-class discussions and group work onto the web. A basic question that needs to be asked, and which has not yet been asked, is: what do these web-based lessons add to the solution of the problem of motivation that is unique, that cannot be solved effectively through non-technological means?

The second problem, related to the first, is that of "coverage." The greater the chronological and geographical scope of the survey course, the harder it is to cover all the material, and the more critical the problem of student motivation becomes. If what I have noted above is true, then students become more interested when there is time to stop and smell the flowers, so to speak, rather than "viewing flowers on horseback," as the Chinese expression goes. I think it is fair to say that none of the Southern California core faculty in this project consciously considered the role of technology in addressing this problem, although it was implicit in their choice of lessons to develop in the web environment. As with the first problem, a next step is to consciously ask the question of whether technology can provide a different or better solution to the problem of "coverage" in the survey course. Is there some new or different way that computer-technology can assist us in addressing this problem?

Finally, we have the problem of the integration of basic skill development with course content. All of us fret about how to organize our courses so that all the relevant periods of history are covered in sufficient depth, while at the same time using the opportunity afforded by the course to teach or reinforce basic skills such as critical reading, writing and analytical thinking. While in theory this interface should work smoothly, in practice it often involves a constant juggling act in the allocation of instructional time between skill development and content coverage. Many faculty members express frustration at what they perceive as their students' low level of basic skill mastery and resent having to "take time away" from the content of the course to spend time working with the class on writing effective theses statements or topic sentences, for example, or ways to develop a good paragraph, or how to read for the main idea.

As with the issues described above, each instructor develops his or her own individual solution to deal with the problem of integration of basic skills, and in general, as in the cases described above, these solutions have generally been made without regard to technological solutions. Indeed, some faculty may feel that adding technology to the mix poses additional problems for the instructor. Not only does one have reading, writing and critical thinking skills to take time away from the course content, but now one has to deal with problems of computer literacy! Rather than being an enhancement, therefore, technology may be seen as a burden by faculty struggling with the problem of covering a great deal of course material.

The task of the Southern California cluster in this AHA project was specifically to see how we could use the new technologies to facilitate the development of critical reasoning skills of students in the survey courses through use of different types of primary sources. The focus on critical thinking derived from our view that history as a discipline lends itself to strengthening of critical reasoning skills, especially by teaching students how to read texts closely and evaluate their utility as historical sources. While historical habits of mind may differ somewhat from critical reasoning as defined in the general education curricula, there is still considerable overlap, and this is where our group of historians wanted to focus their efforts.

As in the case of the other problems delineated above, however, there was some ambiguity in the ways we dealt specifically with the role of technology in addressing this problem. At least three of the six projects (Fitch, Sorenson, Pomerantz) sought to integrate pictorial sources with written texts, and in one case also began to experiment with incorporation of audio-based source materials as well, thereby utilizing one of the important features of the new technology. We have yet to address the question, however, of what is different about using these sources in a computer and Internet-based environment from using multimedia resources in an in-class environment.

Similarly, we did not address ways to use hyperlink technology to specifically focus on basic skill development. For example, we have become accustomed to using spell checkers and sometimes grammar checking software to improve writing and expect our students to use these word processing features. Dictionaries and multimedia encyclopedias are yet other examples of hyperlink reference functions that aid in writing, as is software specifically designed to help students organize essays and develop generalizations. Are there ways we could have used hyperlink functions to aid in critical reasoning skills? Perhaps, this must remain for further research and exploration.

Thus, the Southern California historians who have participated in this project have varied in their approaches to the questions posed above. For all of us, I think it is fair to say that the web-based projects we developed have served as "extras" rather than as "staples" in the survey course "diet." For most of us that diet consists largely of lecture/discussion format, with some emphasizing the former over the latter. For example, one core faculty member, Dave Smith, has developed his own survey teaching method that emphasizes group projects oriented along structured comparative categories for analysis ("Doing World History"); this method was developed for use in an in-class environment and has not been expanded to consider its functioning in a web environment. Others are eclectic, incorporating group work as aspects of class discussion time. As our classes vary in size from about 40 over 100 students, there are different choices instructors make about how to structure in-class as well as out-of-class time.

One further point needs to be noted about the experiences of the core faculty in developing their materials, and that is the problem with fair use of copyrighted materials. For in-class use, instructors tend to be very informal about their use of Xeroxed materials and rarely perceive the need to obtain permission of the author or publisher. For our web-based lessons, however, we had to be very cautious in this regard and could utilize or link only to materials in the public domain. This necessitated considerable searching in some cases, and considerable hand-wringing. In one case, that of Lael Sorenson's lesson, the web-based lesson differs considerably from its printed version because of the constraints the project observed with regard to copyright regulations.

In general, the core faculty approached the problem of their "assignment" in this project by thinking about topics and assignments they were already teaching, and seeing how those topics and assignments could "translate" to the web environment. This is a reflection of our current level of understanding of technology and its impact on learning. If we consider teaching, especially the integration of new technologies into teaching, as a developmental process, then this project has served to provide each of us with a "snapshot" of our stage of development at this particular point. I think that as the technologies become more familiar and more transparent, we will become more sophisticated in our thinking about their role in the teaching and learning process and more adept at using them to inform our work.

Towards a New Paradigm?

In November 2000 my campus (relatively small and underfunded, beset with many of the same problems experienced by other small, relatively poor colleges nationwide) celebrated its first ever "Technology Day." This day-long program provided an opportunity for the campus community to learn about the technological infrastructure that has been put in place during the past few years on our campus. In the past ten years, approximately $2-$2.5 million has been spent (in campus, CSU system, and federal funds) to upgrade the campus "backbone" and to purchase up-to-date desktop PCs for each faculty office. Starting next year, the University plans to provide each class and each faculty member with individual web sites, so that on-line discussion groups, class sessions and examinations, in addition to web-based lessons and assignments, will be feasible. Additionally, in the next couple of years, "smart" classrooms will be constructed throughout the campus, giving faculty instant access to our multimedia resources in their classrooms, including digitized films and videotapes. Faculty will be able to access Internet sites directly in the classroom as well, and students will have enhanced Internet access from campus computer labs and from terminals at student housing facilities.

One may think that even the relatively modest capital investment made by my university is beyond the means of many struggling colleges and universities in the US, but on the contrary, it is within the resources of many more. My university is about in the middle of the nationwide curve technologically. It is also worth noting that the rapid expansion of wireless technology may soon lower even these relatively modest capital outlay costs. The wireless revolution is presently enabling the "have nots" to leap directly into a wireless-based technological transformation without much capital outlay at all. This means that what I have described above either has happened already at your institution, or will be happening soon. We in higher education will soon no longer be able to think of ourselves as "have nots" with respect to the "digital divide," and it is time to examine the possibilities embodied in the new educational technologies and to think about what implications they hold for the teaching and learning process in our field.

We are in the midst of an era in which many changes are occurring in higher education, some but not all of them fueled by new communications technologies. In particular, Internet technology is facilitating an explosion in distance learning or mediated instruction courses and programs. The web-based projects developed in the AHA's "Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age" are ambiguous as to the ways they might be used by instructors. They might be used as an adjunct to the traditional survey classroom, or they could conceivably form part of a course taught entirely through Internet-based distance learning. Both non-profit and for-profit educational institutions are experimenting with the use of synchronous and asynchronous instructional modes that allow students to take courses "anywhere, anytime," at their own convenience, a phenomenon that may be a fad but more likely is not.

From teacher-centered instruction, the focus shifts with computer-based technologies, subtly or not so subtly, to student-centered learning. The student's active learning is facilitated in that the computer-using student is in a better position to direct his or her own access to information through use of the Internet. This possibility carries with it enormous potential for shifts in the teaching and learning process.

The changes in the "teaching" part of the "teaching and learning process" as a result of the new educational technologies are more readily apparent than are those in the "learning" part. As we undergo transformation from a teaching-centered to a learning-centered model, from passivity to activity on the part of the student, and from information-centered to analysis-centered as to course content, it appears that the role of the instructor is diminished. From master of the classroom, quite literally dominating the classroom from the lectern, the instructor now becomes a guide or facilitator. It is a more modest, and perhaps a more passive role than that to which we are accustomed, and instructors may feel that they have less control over their student's learning. The outcomes seem even more intangible and transient than in the conventionally taught class, because at least in the traditional classroom we knew that something had happened, because we made it happen. As noted recently by Lloyd Armstrong in Change , the publication of the American Association of Higher Education, the role of the instructor in the new educational technology is now "unbundled," with potential that poses many problematic issues for us as faculty:

The knowledgeable professor defines the material to be taught; experts in multimedia pedagogy create the structure of the course, technical people implement it; and assessment experts evaluate the course's success in enabling students to learn. The resulting course may contain lectures by the professor who defined the course, a multiplicity of experts lecturing on specific points, or lectures by a hired presenter to reinforce the course's concepts, or it is also possible the course may have no "talking heads" at all. 3

It is more difficult to get at the changes we might anticipate in the "learning" part of the "teaching and learning process" under this technological transformation. Instructors who have taught recently using asynchronous Internet transmissions report anecdotally that they feel their students are more actively engaged in the class material through the virtual discussion groups and greater opportunity for student-instructor interaction. 4

But to date the research on student learning in distance learning or mediated instruction environments is generally unhelpful in addressing more concretely the question of how or in what ways the student learning differs from that in the traditional classroom. Much of the research has framed this issue in terms of whether or not the learning in distance learning is comparable with that in on-campus classrooms, by looking at various equivalencies, e.g., whether the student is receiving the same level of quality in instruction and services, and by examining student attitudes towards their educational experience in the distance learning environment. Although a great deal of effort is going into the study of these questions (by accrediting bodies and funding agencies, for example), to date the research is inconclusive. 5

The "Teaching and Learning in the Digital Age" project has provided us with the opportunity to reflect upon these issues as we developed our materials and began teaching with them. It think it is fair to say that we are still at the stage of framing questions for research and reflection. Because we as a group have been at such an early stage in our understanding of the new instructional technologies, our formulation of these questions is still tentative. There are two areas of particular interest and concern to historians, however, with regard to the impact of computer technology on student learning. These are, first, the implications for short-range versus sustained examination of materials and concepts, and the second concerns the distinction between linear and associational thinking.

In her thoughtful reflective essay, Nancy Fitch has speculated about the inherent distinctiveness of texts in their printed and electronic forms. 6 In the latter, text is limited by the size of the computer monitor rather than by the size of the printed page, and the thrust of the technology leads to fewer lines, fewer words, and a more distinctive graphic arrangement of text on the screen. Readers become accustomed to taking in text a screen at a time. We can speculate on the unhappy implications of this mode of reading for historical thinking skill and critical reasoning skill development, but these speculations remain just that at present. This is clearly an area of research that historians will find of great interest.

The second area of interest concerns the distinction between linear and associational modes of thought. At least part of the package of "historical habits of mind," particularly chronological thinking development, is linear in nature, as is what we commonly think of as "logical" thought patterns stressed in critical reasoning. Yet we are all aware that hyperlink technology facilitates associational thought, wherein the way links are structured on the Internet enables the student to break out of the instructor's proscribed linear progression into a vastly wider world of associations.

The implications of this shift in thinking modes are yet to be analyzed from the perspective of the historian's craft. Should we be celebrating the creative possibilities of associational thinking, of the prospect of ranging through vast fields of knowledge by means of a few mouse clicks? Should we rethink our goals in the light of this technological shift? Where do linear thinking modes intersect in this new domain, or do they?

These are but two of the types of significant questions around which to frame pedagogical questions in the future. It will take years of experimentation and reflection to arrive at a more sophisticated understanding of how to define or redefine our pedagogical goals in the new era, and how to accomplish our pedagogical goals with the new means at hand. We have made a good beginning, thanks to the American Historical Association and the National Endowment for the Humanities, but it is only a beginning.

1. See, e.g., http://www.digitaldivide.gov/

2. These problems, in my opinion, boil down to the essential problem of attempting to incorporate a constructivist learning model into the structure of the survey course. They seem antithetically opposed, and what emerges is an uneasy hybrid.

3. Lloyd Armstrong, "Distance Learning: An Academic Leader's Perspective on a Disruptive Product," Change, 32.6 (Nov.-Dec. 2000) 20-27.

4. Ronald Bergman, November 14, 2000.

5. "What's the Difference? A Review of Contemporary Research on the Effectiveness of Distance Learning in Higher Education," Institute for Higher Education Policy, April 1999.

6. Nancy Fitch, " Reflective Essay ."

The digital divide - An introduction

door Alexander van Deursen en Jan van Dijk

During the 1990s, researchers and policy makers began discussing the presence of a so-called “digital divide,” a distinction of people who do and do not have access to information and communication technologies (ICTs). The concept of the digital divide stems from a comparative perspective of social and information inequality and depends on the idea that there are benefits associated with ICT access and usage and negative consequences attending non-access and usage. Originally, the term “digital divide” mostly referred to gaps in access to computers. When the Internet became widely accessible in society and began to provide a primary means of computing, the term shifted to encompass gaps in Internet access. Defining the digital divide in terms of access to the Internet is now the most popular convention. However, other digital equipment such as mobile telephony and digital television are not ruled out by some users of the term digital divide.

The term digital divide probably has caused more confusion than clarification. According to Gunkel (2003) it is a deeply ambiguous term in the sharp dichotomy it refers to. Van Dijk (2005) has warned against a number of pitfalls of this metaphor. First, the metaphor suggests a simple divide between two clearly divided groups with a yawning gap between them. In fact the divide is more like a spectrum with on the one side people who use computers and the Internet for about every daily task and the people not using them at all at the other side. Secondly, it suggests that the gap is very difficult to bridge. A third misunderstanding might be the impression that the divide is about absolute inequalities, that is between those included and those excluded. In reality most inequalities of the access to digital technology observed are more of a relative kind (see below). A final wrong connotation might be the suggestion that the divide is a static condition while in fact the gaps observed are continually shifting.

An important theoretical distinction concerned is that between individualistic and relational conceptions of social inequality. The first conception departs from so-called methodological individualism (Wellman and Berkowitz, 1988). Differential access to information and computer technologies (ICTs) is related to individuals and their characteristics: level of income and education, employment, age, sex, and ethnicity, to mention the most important ones. This is the usual approach in survey research, which measures the properties of individual respondents. Making multivariate analyses of several individual properties and aggregating them to produce properties of collectivities, one hopes to find background explanations. An alternative notion of inequality uses a relational or network approach (Wellman and Berkowitz, 1988). Here the prime units of analysis are not individuals but the positions of individuals and the relationships between them. Inequality is not primarily a matter of individual attributes but of categorical differences between groups of people. This is the point of departure of the pioneering work Durable Inequality by the American sociologist Charles Tilly (1999). “The central argument runs like this: Large, significant inequalities in advantages among human beings correspond mainly to categorical differences such as black/white, male/female, citizen/foreigner, or Muslim/Jew rather than to individual differences in attributes, propensities, or performances” (Tilly, p. 7). In this conception gender inequality in using ICTs, for example, is not explained by the presumed characteristics of males and females (females having less technical interest etc.) but by the gender relations between them in which males first appropriate new technologies and exclude females in daily practice..

Despite these conceptual problems the term “digital divide” drew attention to the important issue of information inequality in scholarly and political communities at the turn of the century. Countries increasingly realized that the digital divide reduces the potential of the labor force and of innovation. Information and communication technologies were considered to be a growth sector in the economy that should be supported in global competition. Between 2000 and 2004, scientific and policy conferences concerning the digital divide were exceedingly popular, but attention to this matter began to decline in 2004 and 2005 (Van Dijk, 2006). On political and policy-making fronts, many observers, particularly those in rich, developed countries, reached the conclusion that the problem was almost solved, as a rapidly increasing majority of their inhabitants obtained access to computers, the Internet and other digital technologies.

The common current opinion among policy makers and the public at large is that the divide is closing between those who do and do not have access to computers, the Internet and other digital media. In some countries, Internet connection rates in households have reached the figure of 90 percent. Computers, mobile telephony, digital televisions and other digital media are becoming cheaper by the day, while their capacity to perform complex tasks increases. These media are introduced on a massive scale and into all aspects of everyday life. Several applications appear so easy to use that basic literacy supposedly is the sole prerequisite for using them. However, simultaneously defining the digital divide in terms of physical access to a technology is considered superficial by digital divide researchers; physical access alone is no longer considered to be the most important factor explaining information superiority observed. The emphasis is shifting to new dimensions, that is inequalities of skills and usage.

DIMENSIONS OF THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

First dimension: physical and material access

An important reason for the decreasing attention given to the digital divide in the first decade of the 21st century may lies in the fact that divides in physical access to the Internet are closing in most western countries. Concerns about acquiring physical access to digital media have completely dominated public opinion and policy perspectives in the last two decades. Indeed, these concerns are still paramount, as many people think the digital divide is closing because 90 percent of the population or more have access to a computer and the Internet. Such a number would put the Internet on a par with television as a media source. One should note that the diffusion of the Internet in the last two decades has occurred even faster than that of television. However, on a global scale the situation is different; in 2010 Internet access was estimated between 20 and 25 percent of the world population, while in many developing countries, Internet access is still restricted to less than ten percent of the population (UN/ITUstatistics).

Moreover, physical access is not equal to material access. Material access includes all costs related to the use of computers, connections, peripheral equipment, software and services. These costs are diverging in many ways, and people with physical access have very different computer, Internet and other digital media expenses. Considering the current economic crisis in the Western world, the problem of material access to computer and Internet resources for particular parts of the population might become more serious. In this regard, several scholars have pointed toward mobile phones and other portables such as tablet computers as technologies that have the potential to reduce the digital access divide. Mobile phones offer a more affordable means of access to the Internet than computers do when only simple applications that require small data capacity are used (Akiyoshi and Ono, 2008). They are supposed to offer a viable alternative for developing countries. However, one should also keep in mind that mobile phones are by no means a substitute for computers as they lack many advanced applications.

Whatever opportunities mobile phones offer, it is certainly a misconception to think that physical or material access to the Internet automatically bring all the benefits associated with Internet use. Indeed, it is rather schematic and superficial to conceive the digital divide in terms of a binary classification between those with and without physical access to computers or the Internet. Such a belief directly links rates of access to differences in material resources: one either does, or does not have the resources to establish a connection to the Internet. Moreover, such a belief assumes that having a connection correlates with having access to all the advantages the Internet offers. Compaine (2001), for instance, relied on the Diffusion of Innovations (DI) theory of Everett Rogers (1963/1995), who theorized that innovations would spread through society in an S-curve. The S-curve measures the relative speed with which members of a social system adopt a particular innovation and focuses on the time required for that innovation to be adopted by a certain percentage of the system (Rogers, 1995). The adoption rate accelerates at a first tipping point, called critical mass; at this point, an innovation has been so widely adopted that its continued adoption is self-sustaining (Markus, 1987). At a second tipping point diffusion begins to slow down as the market starts to reach saturation. Here the access divide starts to close. Van Dijk (2012) has portrayed the current situation of the physical access divide on a world scale in terms of the S-curve with the locations of developed and developing countries mapped into it.

The two curved lines in Figure 1 are splitting the main curved line that has the shape of a S to indicate that we have two sides or populations in the digital divide with different representations of the S-curve (that portrays the average). One curve is for those on the ‘wrong’ side of the digital divide, usually people with low education, low income and higher age and those on the ‘right’ side of the divide, mostly people with high education, high income and lower age. When the two lines come together the physical access divide is closing. However, at this point in time we still do not know whether it will close completely – this is called ‘normalization’ in the Figure - or that a gap will remain because the social categories in the higher curve continue to have a lead because they first adopt every new innovation in the field of digital media (for example the transition from narrowband to broadband). This is called ‘stratification’ by Norris (2001).

If Compaine and van Dijk were correct in applying DI theory to the digital divide, increases in physical access to the Internet would no doubt correspond to the S-curve measuring the adoption of innovations. From this point of view, the digital divide should steadily disappear as the diffusion rate reaches saturation, particularly when ‘normalization’ applies. The likelihood of the correspondence between the declining digital divide and the increasing rate of innovation diffusion would further be augmented as a result of the migration of the Internet to platforms such as digital television and mobile phones; indeed, the mistaken notion that the digital divide is a temporary problem of physical access has been reinforced by these migrations (Golding and Murdock, 2001). However, there are serious problems with applying the DI theory to the study of computer and Internet diffusion (Norris, 2001; Van Dijk and Hacker, 2003). Van Dijk (2005: 62-65) mentions several weak assumptions of this theory. First, why should the diffusion of each medium necessarily reach a hundred percent? Instead of this ‘normalization’ it might stop far before the stage of population-wide diffusion or become stratified (some categories keep adopting more and earlier than others). Second, while the DI theory assumes the existence of a single confined medium that does not change, in fact digital media devices often are combined (multimedia) and they continually change in functionality, quality, price and appearance (think about the history of the PC), Finally, the determinism of DI theory is striking: why should there be innovators, early adopters and early or late majority users with every medium?

Other dimensions come forwards: the second-level digital divide

Because it is wrong to assume that physical access to computers and the Internet automatically entails all benefits associated with their use, the digital divide should not be considered as a divide of physical access only. In the literature about the digital divide published after 2000, this conclusion comes forward stronger and stronger. Other dimensions have come forwards. Kling (2000), for instance, suggested a distinction between technical access (i.e., material availability) and social access (i.e., professional knowledge and technical skills necessary to benefit from information technologies). Attewell (2001) distinguished between a first digital divide and a second digital divide. Hargittai (2002), however, suggested what has become perhaps the most familiar distinction: that between first- and second-level digital divides. Besides these dimensions Warschauer (2003) also argued that factors such as content, language, literacy, educational level attained, and institutional structure must be considered. Van Dijk (2005) proposed a causal model with four types of access to ICTs: motivational access (e.g., the lack of the elementary digital experience by people who have no interest or feel hostile toward ICTs), physical access (e.g., the availability of ICTs), digital skills (e.g., the ability to use ICTs), and usage access (the opportunity and practice of using ICTs). He calls the shift from physical access to skills and usage a ‘deepening divide’ as unequal skills and usage are deeply entrenched in existing social inequalities and because they will deepen these inequalities again.

The dimension of motivation

Each of these scholars shares the following view: while gaps in physical access might be closing in certain respects, other digital divides have begun to grow. In his discussion of motivation access, for instance, van Dijk (2005) argues that the wish to have a computer and a connection to the Internet precedes physical access. Thus, many of those who remain on the excluded side of the digital divide do so for motivational reasons. According to van Dijk, there are not only ‘have-nots’ but also ‘want-nots.’ At the start of the diffusion of new technologies, motivational concerns are the strongest forces to stimulate or prevent the acceptance of those technologies. In several European and American surveys conducted between 1999 and 2003, half of those individuals unconnected to the Internet explicitly stated that they would refuse to seek a connection for the following reasons: no need or significant usage opportunities, no time or liking, rejection of the medium (e.g., Internet and computer games viewed as ‘dangerous’ media), lack of money, or lack of skills (e.g. ARD-ZDF, 1999b and a Pew Internet and American Life survey: Lenhart, Horrigan, Rainie et al., 2003). These observations lead us to one of the most confusing myths produced by popular ideas about the digital divide: that people are either in or out, included or excluded. To explain people’s motivations for using digital technologies, mental and psychological conditions are often mentioned in literature about the digital divide. Here, the phenomena of computer anxiety and techno-phobia are still relevant and continue to create barriers to computer and Internet access in many countries, especially among seniors, people with low educational background and segments of the female population (Brosnan, 1998, Chua, Chen and Wong, 1999, Rockwell and Singleton, 2002, UCLA, 2003)).

The skill dimension

In contemporary literature, inequality of Internet skills increasingly is acknowledged as a key dimension of the digital divide. Several terms are used to frame Internet skills, e.g. digital or information literacy, computer skills, ICT literacy or web fluency. To date, very little scientific research has focused on the actual level of digital skills possessed by various populations. Many large-scale surveys have revealed dramatic differences in skills among populations, including those populations in countries experiencing the extensive diffusion of new media (Van Dijk, 2005; Warschauer, 2003). Nevertheless, these surveys measure actual levels of digital skills only by asking respondents to estimate their own proficiency.

A better way to obtain valid and complete measurements of digital skills is to implement performance tests; such tests would require participants to perform those computer and Internet tasks that are regularly performed in daily life. Hargittai (2002) has begun to implement performance tests in this field. Asking 54 demographically diverse Americans to perform different Internet search tasks, she discovered enormous differences in levels of accomplishment and in the time needed to complete the tasks. In the Netherlands, Van Deursen and Van Dijk (2010, 2011) conducted performance tests in a university media lab on a cross-section of the Dutch population; more than 300 people were tested. Subjects who took the test showed a fairly high level of basic operational and formal skills, but they experienced much more difficulty in processing content-related information and in exercising strategic skills.

The results showed significant differences in performance between people of different ages and levels of education. Age primarily appears to be a significant contributor to the basic skills to use the Internet medium-related skills, as younger people perform better on these skills than older people do. In contrast, older individuals performed better where content-related skills, including information and strategic skills, were needed; this occurred in all instances where the older individuals possessed an adequate level of medium-related skills. However, because many seniors tend to lack medium-related Internet skills, they are seriously limited in their content-related skills. Nevertheless, this observation provides another perspective on popular notions about the abilities of the so-called ‘digital generation.’ It also shows that the skills inequality problem will not automatically disappear in the future and that life experience and substantial education of all kinds remain vital for acquiring digital skills.

The usage dimension

Aside from divergences in skill levels, the digital divide debate has increasingly drawn attention to the actual usage of the Internet. As a dependent factor, Internet use can be measured in several ways (e.g., usage time and frequency; number and diversity of usage applications; broadband or narrowband use; more or less active or creative use). Statistics regarding usage time and frequency are notoriously unreliable, as they rely on shifting and divergent operational definitions that are often determined by market research bureaus. These statistics give only some indication of the difference between actual use and physical access. It is certain, for example, that actual use diverges greatly from potential use. Furthermore, those who have a computer and/or Internet connection not always actually use them. Many assumed users actually use the computer or the Internet only once a week or a few times a month; some people never use them.

It is important to understand that when a physical access gap for a particular social category closes, usage of the medium concerned does not automatically equalize. Here the concept of ‘usage gap’ might apply. This concept is comparable to the concept ‘knowledge gap’ created in the 1970s by Tichenor, Donohue and Olien (1970). While the knowledge gap concerns the differential derivation of knowledge achieved through mass media and focuses, in particular, on mass media’s influence on perception and cognition, the usage gap concept is much broader and potentially more effective in terms of social inequality because this gap concerns differential uses of and activities with computers and the Internet in all spheres of daily life, not just the derivation of knowledge.

The usage gap closures becomes most apparent when looking at types of usage. It is generally assumed that some Internet activities are more beneficial or advantageous for Internet users than others. Some activities offer users more chances and resources to move forward in their career, work, education and societal position than others that are mainly consumptive or entertaining (e.g., Hargittai and Hinnant, 2008; Kim and Kim, 2001; Mossberger, Tolbert and Stansbury, 2003; Van Dijk, 2005; Wasserman and Richmond-Abbott, 2005). In terms of the theories of capital inspired by Bourdieu (1984), one could also say that certain Internet activities allow users to accrue more economic, social and cultural capital and resources than other activities. While some sections of the population will more frequently use those applications that have the greatest advantages for accruing capital and resources (work, career, study, societal participation, etc.), other sections will choose to use those entertainment applications that have little or no advantage for accruing capital and resources (e.g., van Dijk, 1999; Bonfadelli, 2002; Park, 2002; Zillien and Hargittai, 2009).

These differences in types of Internet use call into question the belief that growing up in a digital world results in an intuitive and unproblematic use of digital technologies (see Prensky, 2001). A difference exists between the personal and purposeful uses of technologies such as the Internet. Recently, several scholars have addressed the digital divide by attempting to classify Internet usage types. Some of these classifications take the uses-and-gratifications approach (Katz, Blumler and Gureitch, 1974) as a starting point, while others make use of the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989) or Social Cognitive Theory. Finally, there are scholars who account for differences in usage by grouping Internet users into use typologies (e.g., Ortega Egea, Menéndez and González, 2007).

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE AND INEQUALITY