- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

23.1: The Relationship Between Inflation and Unemployment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4473

The Phillips Curve

The Phillips curve shows the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment: as unemployment decreases, inflation increases.

learning objectives

- Review the historical evidence regarding the theory of the Phillips curve

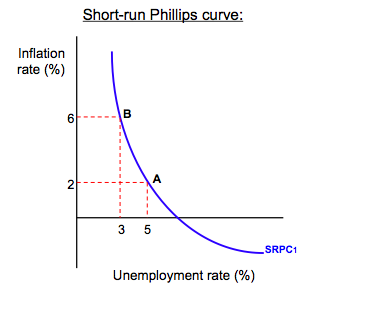

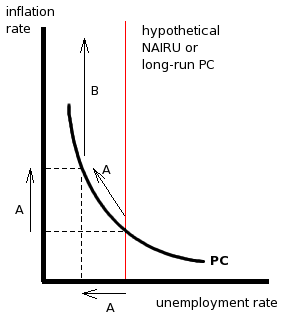

The Phillips curve relates the rate of inflation with the rate of unemployment. The Phillips curve argues that unemployment and inflation are inversely related: as levels of unemployment decrease, inflation increases. The relationship, however, is not linear. Graphically, the short-run Phillips curve traces an L-shape when the unemployment rate is on the x-axis and the inflation rate is on the y-axis.

Theoretical Phillips Curve : The Phillips curve shows the inverse trade-off between inflation and unemployment. As one increases, the other must decrease. In this image, an economy can either experience 3% unemployment at the cost of 6% of inflation, or increase unemployment to 5% to bring down the inflation levels to 2%.

The early idea for the Phillips curve was proposed in 1958 by economist A.W. Phillips. In his original paper, Phillips tracked wage changes and unemployment changes in Great Britain from 1861 to 1957, and found that there was a stable, inverse relationship between wages and unemployment. This correlation between wage changes and unemployment seemed to hold for Great Britain and for other industrial countries. In 1960, economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow expanded this work to reflect the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Because wages are the largest components of prices, inflation (rather than wage changes) could be inversely linked to unemployment.

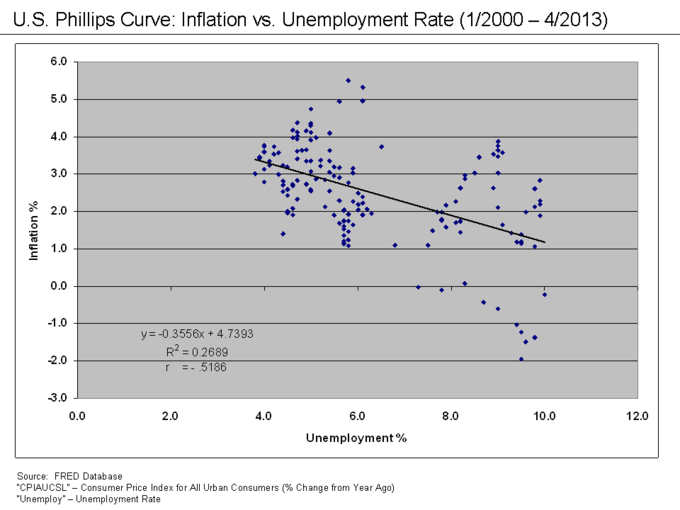

The theory of the Phillips curve seemed stable and predictable. Data from the 1960’s modeled the trade-off between unemployment and inflation fairly well. The Phillips curve offered potential economic policy outcomes: fiscal and monetary policy could be used to achieve full employment at the cost of higher price levels, or to lower inflation at the cost of lowered employment. However, when governments attempted to use the Phillips curve to control unemployment and inflation, the relationship fell apart. Data from the 1970’s and onward did not follow the trend of the classic Phillips curve. For many years, both the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment were higher than the Phillips curve would have predicted, a phenomenon known as “stagflation. ” Ultimately, the Phillips curve was proved to be unstable, and therefore, not usable for policy purposes.

US Phillips Curve (2000 – 2013) : The data points in this graph span every month from January 2000 until April 2013. They do not form the classic L-shape the short-run Phillips curve would predict. Although it was shown to be stable from the 1860’s until the 1960’s, the Phillips curve relationship became unstable – and unusable for policy-making – in the 1970’s.

The Relationship Between the Phillips Curve and AD-AD

Changes in aggregate demand cause movements along the Phillips curve, all other variables held constant.

- Relate aggregate demand to the Phillips curve

The Phillips Curve Related to Aggregate Demand

The Phillips curve shows the inverse trade-off between rates of inflation and rates of unemployment. If unemployment is high, inflation will be low; if unemployment is low, inflation will be high.

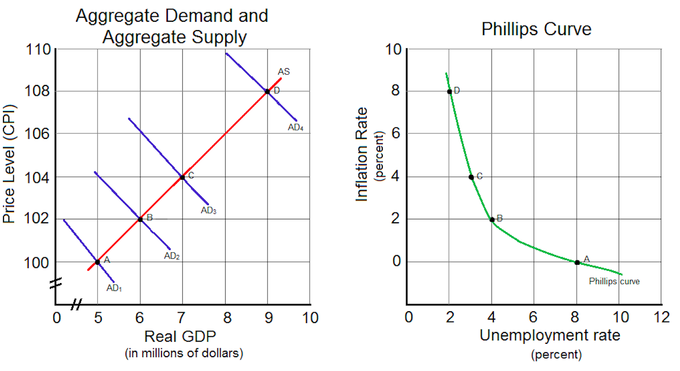

The Phillips curve and aggregate demand share similar components. The Phillips curve is the relationship between inflation, which affects the price level aspect of aggregate demand, and unemployment, which is dependent on the real output portion of aggregate demand. Consequently, it is not far-fetched to say that the Phillips curve and aggregate demand are actually closely related.

To see the connection more clearly, consider the example illustrated by. Let’s assume that aggregate supply, AS, is stationary, and that aggregate demand starts with the curve, AD 1 . There is an initial equilibrium price level and real GDP output at point A. Now, imagine there are increases in aggregate demand, causing the curve to shift right to curves AD 2 through AD4. As aggregate demand increases, unemployment decreases as more workers are hired, real GDP output increases, and the price level increases; this situation describes a demand-pull inflation scenario.

Phillips Curve and Aggregate Demand : As aggregate demand increases from AD1 to AD4, the price level and real GDP increases. This translates to corresponding movements along the Phillips curve as inflation increases and unemployment decreases.

As more workers are hired, unemployment decreases. Moreover, the price level increases, leading to increases in inflation. These two factors are captured as equivalent movements along the Phillips curve from points A to D. At the initial equilibrium point A in the aggregate demand and supply graph, there is a corresponding inflation rate and unemployment rate represented by point A in the Phillips curve graph. For every new equilibrium point (points B, C, and D) in the aggregate graph, there is a corresponding point in the Phillips curve. This illustrates an important point: changes in aggregate demand cause movements along the Phillips curve.

The Long-Run Phillips Curve

The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment, so inflation and unemployment are unrelated in the long run.

- Examine the NAIRU and its relationship to the long term Phillips curve

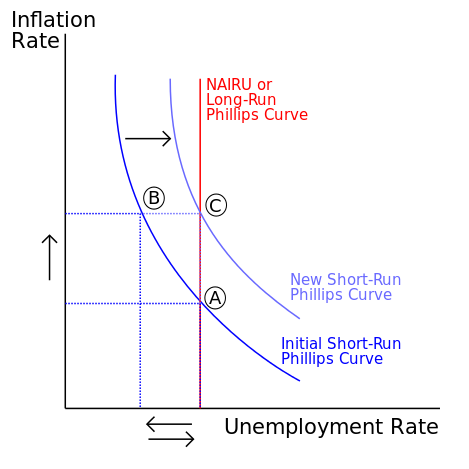

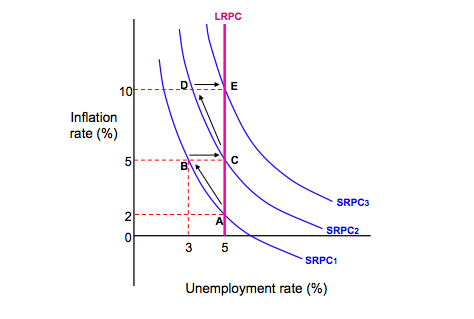

The Phillips curve shows the trade-off between inflation and unemployment, but how accurate is this relationship in the long run? According to economists, there can be no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run. Decreases in unemployment can lead to increases in inflation, but only in the short run. In the long run, inflation and unemployment are unrelated. Graphically, this means the Phillips curve is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment, or the hypothetical unemployment rate if aggregate production is in the long-run level. Attempts to change unemployment rates only serve to move the economy up and down this vertical line.

Natural Rate Hypothesis

The natural rate of unemployment theory, also known as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) theory, was developed by economists Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps. According to NAIRU theory, expansionary economic policies will create only temporary decreases in unemployment as the economy will adjust to the natural rate. Moreover, when unemployment is below the natural rate, inflation will accelerate. When unemployment is above the natural rate, inflation will decelerate. When the unemployment rate is equal to the natural rate, inflation is stable, or non-accelerating.

To get a better sense of the long-run Phillips curve, consider the example shown in. Assume the economy starts at point A and has an initial rate of unemployment and inflation rate. If the government decides to pursue expansionary economic policies, inflation will increase as aggregate demand shifts to the right. This is shown as a movement along the short-run Phillips curve, to point B, which is an unstable equilibrium. As aggregate demand increases, more workers will be hired by firms in order to produce more output to meet rising demand, and unemployment will decrease. However, due to the higher inflation, workers’ expectations of future inflation changes, which shifts the short-run Phillips curve to the right, from unstable equilibrium point B to the stable equilibrium point C. At point C, the rate of unemployment has increased back to its natural rate, but inflation remains higher than its initial level.

NAIRU and Phillips Curve : Although the economy starts with an initially low level of inflation at point A, attempts to decrease the unemployment rate are futile and only increase inflation to point C. The unemployment rate cannot fall below the natural rate of unemployment, or NAIRU, without increasing inflation in the long run.

The reason the short-run Phillips curve shifts is due to the changes in inflation expectations. Workers, who are assumed to be completely rational and informed, will recognize their nominal wages have not kept pace with inflation increases (the movement from A to B), so their real wages have been decreased. As such, in the future, they will renegotiate their nominal wages to reflect the higher expected inflation rate, in order to keep their real wages the same. As nominal wages increase, production costs for the supplier increase, which diminishes profits. As profits decline, suppliers will decrease output and employ fewer workers (the movement from B to C). Consequently, an attempt to decrease unemployment at the cost of higher inflation in the short run led to higher inflation and no change in unemployment in the long run.

The NAIRU theory was used to explain the stagflation phenomenon of the 1970’s, when the classic Phillips curve could not. According to the theory, the simultaneously high rates of unemployment and inflation could be explained because workers changed their inflation expectations, shifting the short-run Phillips curve, and increasing the prevailing rate of inflation in the economy. At the same time, unemployment rates were not affected, leading to high inflation and high unemployment.

The Short-Run Phillips Curve

The short-run Phillips curve depicts the inverse trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

- Interpret the short-run Phillips curve

The Phillips curve depicts the relationship between inflation and unemployment rates. The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line that illustrates that there is no permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run. However, the short-run Phillips curve is roughly L-shaped to reflect the initial inverse relationship between the two variables. As unemployment rates increase, inflation decreases; as unemployment rates decrease, inflation increases.

Short-Run Phillips Curve : The short-run Phillips curve shows that in the short-term there is a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. Contrast it with the long-run Phillips curve (in red), which shows that over the long term, unemployment rate stays more or less steady regardless of inflation rate.

Consider the example shown in. When the unemployment rate is 2%, the corresponding inflation rate is 10%. As unemployment decreases to 1%, the inflation rate increases to 15%. On the other hand, when unemployment increases to 6%, the inflation rate drops to 2%.

Historical application

During the 1960’s, the Phillips curve rose to prominence because it seemed to accurately depict real-world macroeconomics. However, the stagflation of the 1970’s shattered any illusions that the Phillips curve was a stable and predictable policy tool. Nowadays, modern economists reject the idea of a stable Phillips curve, but they agree that there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the short-run. Given a stationary aggregate supply curve, increases in aggregate demand create increases in real output. As output increases, unemployment decreases. With more people employed in the workforce, spending within the economy increases, and demand-pull inflation occurs, raising price levels.

Therefore, the short-run Phillips curve illustrates a real, inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment, but this relationship can only exist in the short run . The idea of a stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run has been disproved by economic history.

Relationship Between Expectations and Inflation

There are two theories of expectations (adaptive or rational) that predict how people will react to inflation.

- Distinguish adaptive expectations from rational expectations

The short-run Phillips curve is said to shift because of workers’ future inflation expectations. Yet, how are those expectations formed? There are two theories that explain how individuals predict future events.

Real versus Nominal Quantities

To fully appreciate theories of expectations, it is helpful to review the difference between real and nominal concepts. Anything that is nominal is a stated aspect. In contrast, anything that is real has been adjusted for inflation. To make the distinction clearer, consider this example. Suppose you are opening a savings account at a bank that promises a 5% interest rate. This is the nominal, or stated, interest rate. However, suppose inflation is at 3%. The real interest rate would only be 2% (the nominal 5% minus 3% to adjust for inflation).

The difference between real and nominal extends beyond interest rates. In an earlier atom, the difference between real GDP and nominal GDP was discussed. The distinction also applies to wages, income, and exchange rates, among other values.

Adaptive Expectations

The theory of adaptive expectations states that individuals will form future expectations based on past events. For example, if inflation was lower than expected in the past, individuals will change their expectations and anticipate future inflation to be lower than expected.

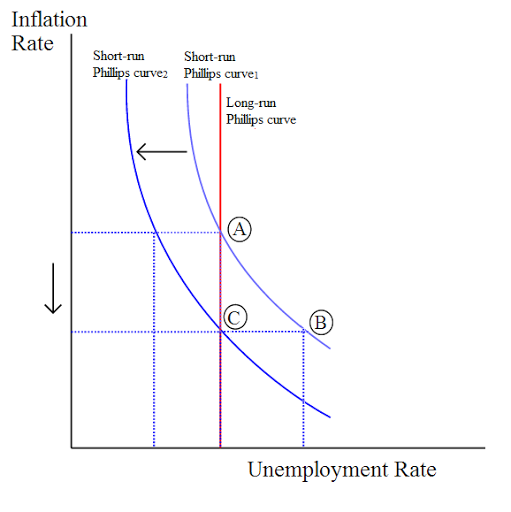

To connect this to the Phillips curve, consider. Assume the economy starts at point A at the natural rate of unemployment with an initial inflation rate of 2%, which has been constant for the past few years. Accordingly, because of the adaptive expectations theory, workers will expect the 2% inflation rate to continue, so they will incorporate this expected increase into future labor bargaining agreements. This way, their nominal wages will keep up with inflation, and their real wages will stay the same.

Expectations and the Phillips Curve : According to adaptive expectations theory, policies designed to lower unemployment will move the economy from point A through point B, a transition period when unemployment is temporarily lowered at the cost of higher inflation. However, eventually, the economy will move back to the natural rate of unemployment at point C, which produces a net effect of only increasing the inflation rate.According to rational expectations theory, policies designed to lower unemployment will move the economy directly from point A to point C. The transition at point B does not exist as workers are able to anticipate increased inflation and adjust their wage demands accordingly.

Now assume that the government wants to lower the unemployment rate. To do so, it engages in expansionary economic activities and increases aggregate demand. As aggregate demand increases, inflation increases. Because of the higher inflation, the real wages workers receive have decreased. For example, assume each worker receives $100, plus the 2% inflation adjustment. Each worker will make $102 in nominal wages, but $100 in real wages. Now, if the inflation level has risen to 6%. Workers will make $102 in nominal wages, but this is only $96.23 in real wages.

Although the workers’ real purchasing power declines, employers are now able to hire labor for a cheaper real cost. Consequently, employers hire more workers to produce more output, lowering the unemployment rate and increasing real GDP. On, the economy moves from point A to point B.

However, workers eventually realize that inflation has grown faster than expected, their nominal wages have not kept pace, and their real wages have been diminished. They demand a 4% increase in wages to increase their real purchasing power to previous levels, which raises labor costs for employers. As labor costs increase, profits decrease, and some workers are let go, increasing the unemployment rate. Graphically, the economy moves from point B to point C.

This example highlights how the theory of adaptive expectations predicts that there are no long-run trade-offs between unemployment and inflation. In the short run, it is possible to lower unemployment at the cost of higher inflation, but, eventually, worker expectations will catch up, and the economy will correct itself to the natural rate of unemployment with higher inflation.

Rational Expectations

The theory of rational expectations states that individuals will form future expectations based on all available information, with the result that future predictions will be very close to the market equilibrium. For example, assume that inflation was lower than expected in the past. Individuals will take this past information and current information, such as the current inflation rate and current economic policies, to predict future inflation rates.

As an example of how this applies to the Phillips curve, consider again. Assume the economy starts at point A, with an initial inflation rate of 2% and the natural rate of unemployment. However, under rational expectations theory, workers are intelligent and fully aware of past and present economic variables and change their expectations accordingly. They will be able to anticipate increases in aggregate demand and the accompanying increases in inflation. As such, they will raise their nominal wage demands to match the forecasted inflation, and they will not have an adjustment period when their real wages are lower than their nominal wages. Graphically, they will move seamlessly from point A to point C, without transitioning to point B.

In essence, rational expectations theory predicts that attempts to change the unemployment rate will be automatically undermined by rational workers. They can act rationally to protect their interests, which cancels out the intended economic policy effects. Efforts to lower unemployment only raise inflation.

Shifting the Phillips Curve with a Supply Shock

Aggregate supply shocks, such as increases in the costs of resources, can cause the Phillips curve to shift.

- Give examples of aggregate supply shock that shift the Phillips curve

The Phillips curve shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment. In the short-run, inflation and unemployment are inversely related; as one quantity increases, the other decreases. In the long-run, there is no trade-off. In the 1960’s, economists believed that the short-run Phillips curve was stable. By the 1970’s, economic events dashed the idea of a predictable Phillips curve. What could have happened in the 1970’s to ruin an entire theory? Stagflation caused by a aggregate supply shock.

Stagflation and Aggregate Supply Shocks

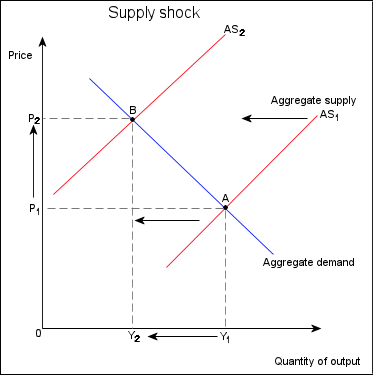

Stagflation is a combination of the words “stagnant” and “inflation,” which are the characteristics of an economy experiencing stagflation: stagnating economic growth and high unemployment with simultaneously high inflation. The stagflation of the 1970’s was caused by a series of aggregate supply shocks. In this case, huge increases in oil prices by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) created a severe negative supply shock. The increased oil prices represented greatly increased resource prices for other goods, which decreased aggregate supply and shifted the curve to the left. As aggregate supply decreased, real GDP output decreased, which increased unemployment, and price level increased; in other words, the shift in aggregate supply created cost-push inflation.

Aggregate Supply Shock : In this example of a negative supply shock, aggregate supply decreases and shifts to the left. The resulting decrease in output and increase in inflation can cause the situation known as stagflation.

Shifting the Phillips Curve

The aggregate supply shocks caused by the rising price of oil created simultaneously high unemployment and high inflation. At the time, the dominant school of economic thought believed inflation and unemployment to be mutually exclusive; it was not possible to have high levels of both within an economy. Consequently, the Phillips curve could not model this situation. For high levels of unemployment, there were now corresponding levels of inflation that were higher than the Phillips curve predicted; the Phillips curve had shifted upwards and to the right. Thus, the Phillips curve no longer represented a predictable trade-off between unemployment and inflation.

Disinflation

Disinflation is a decline in the rate of inflation, and can be caused by declines in the money supply or recessions in the business cycle.

- Identify situations with disinflation

Inflation is the persistent rise in the general price level of goods and services. Disinflation is a decline in the rate of inflation; it is a slowdown in the rise in price level. As an example, assume inflation in an economy grows from 2% to 6% in Year 1, for a growth rate of four percentage points. In Year 2, inflation grows from 6% to 8%, which is a growth rate of only two percentage points. The economy is experiencing disinflation because inflation did not increase as quickly in Year 2 as it did in Year 1, but the general price level is still rising. Disinflation is not to be confused with deflation, which is a decrease in the general price level.

Disinflation can be caused by decreases in the supply of money available in an economy. It can also be caused by contractions in the business cycle, otherwise known as recessions. The Phillips curve can illustrate this last point more closely. Consider an economy initially at point A on the long-run Phillips curve in. Suppose that during a recession, the rate that aggregate demand increases relative to increases in aggregate supply declines. This reduces price levels, which diminishes supplier profits. As profits decline, employers lay off employees, and unemployment rises, which moves the economy from point A to point B on the graph. Eventually, though, firms and workers adjust their inflation expectations, and firms experience profits once again. As profits increase, employment also increases, returning the unemployment rate to the natural rate as the economy moves from point B to point C. The expected rate of inflation has also decreased due to different inflation expectations, resulting in a shift of the short-run Phillips curve.

Disinflation : Disinflation can be illustrated as movements along the short-run and long-run Phillips curves.

Inflation vs. Deflation vs. Disinflation

To illustrate the differences between inflation, deflation, and disinflation, consider the following example. Assume the following annual price levels as compared to the prices in year 1:

- Year 1: 100% of Year 1 prices

- Year 2: 104% of Year 1 prices

- Year 3: 106% of Year 1 prices

- Year 4: 107% of Year 1 prices

- Year 5: 105% of Year 1 prices

As the economy moves through Year 1 to Year 4, there is a continued growth in the price level. This is an example of inflation; the price level is continually rising. However, between Year 2 and Year 4, the rise in price levels slows down. Between Year 2 and Year 3, the price level only increases by two percentage points, which is lower than the four percentage point increase between Years 1 and 2. The trend continues between Years 3 and 4, where there is only a one percentage point increase. This is an example of disinflation; the overall price level is rising, but it is doing so at a slower rate.

Between Years 4 and 5, the price level does not increase, but decreases by two percentage points. This is an example of deflation; the price rise of previous years has reversed itself.

- The relationship between inflation rates and unemployment rates is inverse. Graphically, this means the short-run Phillips curve is L-shaped.

- A.W. Phillips published his observations about the inverse correlation between wage changes and unemployment in Great Britain in 1958. This relationship was found to hold true for other industrial countries, as well.

- From 1861 until the late 1960’s, the Phillips curve predicted rates of inflation and rates of unemployment. However, from the 1970’s and 1980’s onward, rates of inflation and unemployment differed from the Phillips curve’s prediction. The relationship between the two variables became unstable.

- Aggregate demand and the Phillips curve share similar components. The rate of unemployment and rate of inflation found in the Phillips curve correspond to the real GDP and price level of aggregate demand.

- Changes in aggregate demand translate as movements along the Phillips curve.

- If there is an increase in aggregate demand, such as what is experienced during demand-pull inflation, there will be an upward movement along the Phillips curve. As aggregate demand increases, real GDP and price level increase, which lowers the unemployment rate and increases inflation.

- The natural rate of unemployment is the hypothetical level of unemployment the economy would experience if aggregate production were in the long-run state.

- The natural rate hypothesis, or the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) theory, predicts that inflation is stable only when unemployment is equal to the natural rate of unemployment. If unemployment is below (above) its natural rate, inflation will accelerate (decelerate).

- Expansionary efforts to decrease unemployment below the natural rate of unemployment will result in inflation. This changes the inflation expectations of workers, who will adjust their nominal wages to meet these expectations in the future. This leads to shifts in the short-run Phillips curve.

- The natural rate hypothesis was used to give reasons for stagflation, a phenomenon that the classic Phillips curve could not explain.

- The long-run Phillips curve is a vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment, but the short-run Phillips curve is roughly L-shaped.

- The inverse relationship shown by the short-run Phillips curve only exists in the short-run; there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run.

- Economic events of the 1970’s disproved the idea of a permanently stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation.

- Nominal quantities are simply stated values. Real quantities are nominal ones that have been adjusted for inflation.

- Adaptive expectations theory says that people use past information as the best predictor of future events. If inflation was higher than normal in the past, people will expect it to be higher than anticipated in the future.

- Rational expectations theory says that people use all available information, past and current, to predict future events. If inflation was higher than normal in the past, people will take that into consideration, along with current economic indicators, to anticipate its future performance.

- According to adaptive expectations, attempts to reduce unemployment will result in temporary adjustments along the short-run Phillips curve, but will revert to the natural rate of unemployment. According to rational expectations, attempts to reduce unemployment will only result in higher inflation.

- In the 1970’s soaring oil prices increased resource costs for suppliers, which decreased aggregate supply. The resulting cost-push inflation situation led to high unemployment and high inflation ( stagflation ), which shifted the Phillips curve upwards and to the right.

- Stagflation is a situation where economic growth is slow (reducing employment levels) but inflation is high.

- The Phillips curve was thought to represent a fixed and stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation, but the supply shocks of the 1970’s caused the Phillips curve to shift. This ruined its reputation as a predictable relationship.

- Disinflation is not the same as deflation, when inflation drops below zero.

- During periods of disinflation, the general price level is still increasing, but it is occurring slower than before.

- The short-run and long-run Phillips curve may be used to illustrate disinflation.

- Phillips curve : A graph that shows the inverse relationship between the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation in an economy.

- stagflation : Inflation accompanied by stagnant growth, unemployment, or recession.

- aggregate demand : The the total demand for final goods and services in the economy at a given time and price level.

- Natural Rate of Unemployment : The hypothetical unemployment rate consistent with aggregate production being at the long-run level.

- non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment : (NAIRU); theory that describes how the short-run Phillips curve shifts in the long run as expectations change.

- adaptive expectations theory : A hypothesized process by which people form their expectations about what will happen in the future based on what has happened in the past.

- rational expectations theory : A hypothesized process by which people form their expectations about what will happen in the future based on all relevant information.

- supply shock : An event that suddenly changes the price of a commodity or service. It may be caused by a sudden increase or decrease in the supply of a particular good.

- disinflation : A decrease in the inflation rate.

- inflation : An increase in the general level of prices or in the cost of living.

- deflation : A decrease in the general price level, that is, in the nominal cost of goods and services.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SPECIFIC ATTRIBUTION

- Q18-Macro (Is there a long-term trade-off between inflation and unemployment?). Provided by : ib-econ Wikispace. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-M...employment%3F) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips Curve. Provided by : sjhsrc Wikispace. Located at : sjhsrc.wikispaces.com/Phillips+Curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stagflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...phillips-curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- U.S.nPhillips Curve 2000 to 2013. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:U....00_to_2013.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : Wikispaces. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-M...unemployment?) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- aggregate demand. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/aggregate%20demand . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : http://www.boundless.com . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Milton Friedman. Provided by : econwikis-mborg Wikispace. Located at : econwikis-mborg.wikispaces.com/Milton+Friedman . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Natural rate of unemployment. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural...f_unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Natural Rate of Unemployment. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural...20Unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...f-unemployment . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- NAIRU-SR-and-LR. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NAIRU-SR-and-LR.svg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Unit V. Provided by : ap-macroeconomics Wikispace. Located at : ap-macroeconomics.wikispaces.com/Unit+V . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillips_curve . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : Wikispaces. Located at : ib-econ.wikispaces.com/Q18-Macro+(Is+there+a+long-term+trade-off+between+inflation+and+unemployment?) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- PhilCurve.png. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PhilCurve.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Adaptive expectations. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_expectations . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Rational expectations. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Rational_expectations . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Real versus nominal value (economics). Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_ve...ue_(economics) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- adaptive expectations theory. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/adaptiv...tions%20theory . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by : Boundless Learning. Located at : www.boundless.com//economics/...tations-theory . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Supply_shock . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Phillips curve. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillip...%23Stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Stagflation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/supply%20shock . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- stagflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/stagflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Economics supply shock. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ec...pply_shock.png . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Disinflation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Disinflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long-Run AS. Provided by : mchenry Wikispace. Located at : mchenry.wikispaces.com/Long-Run+AS . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- deflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/deflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- inflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/inflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- disinflation. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : en.wiktionary.org/wiki/disinflation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- U.S.nPhillips Curve 2000 to 2013. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:U....00_to_2013.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by : lh5.googleusercontent.com/-B...inflation2.png. Located at : https://lh5.googleusercontent.com/-Bc5Yt-QMGXA/Uo3sjZ7SgxI/AAAAAAAAAXQ/1MksRdza_rA/s512/Phillipscurve_disinflation2.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Labor Supply and Demand

The phillips curve, phillips curve implications.

- Monetarist Rebuttal

Relationship Breakdown

Cpi vs. unemployment, current environment wages, the bottom line.

- Macroeconomics

How Inflation and Unemployment Are Related

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/elvis_picardoimg_1978__e_pic-5bfc2629c9e77c0026b3f1d0.jpg)

The relationship between inflation and unemployment has traditionally been an inverse correlation . However, this relationship is more complicated than it appears at first glance, and it has broken down on a number of occasions over the past 50 years.

Since inflation and employment (and unemployment) are some of the most closely monitored economic indicators, we'll delve into their relationship and how they affect the overall economy.

Key Takeaways

- Inflation and unemployment typically have an inverse correlation but the relationship is a complex one.

- In times of high unemployment, wages typically remain stagnant, and wage inflation (or rising wages) is non-existent.

- In times of low unemployment, employers typically need to pay higher wages to attract employees, ultimately leading to rising wage inflation.

- The Phillips Curve believes that rising wages should lead to higher prices for products and services in an economy, ultimately pushing the overall inflation rate higher.

- Monetarists argue against the Phillips Curve, stating that over the long run, the economy tends to revert to the natural rate of unemployment as it adjusts to any rate of inflation.

When unemployment is high , the number of people looking for work significantly exceeds the number of jobs available. In other words, the supply of labor is greater than the demand for it.

Let's take wage inflation —the rate of change in wages—as a proxy for inflation in the economy. With so many workers available, there's little need for employers to "bid" for the services of employees by paying them higher wages. In times of high unemployment, wages typically remain stagnant, and wage inflation (or rising wages) is non-existent.

In times of low unemployment , the demand for labor by employers exceeds the supply. In such a tight labor market, employers typically need to pay higher wages to attract employees, ultimately leading to rising wage inflation.

Over the years, economists have studied the relationship between unemployment and wage inflation, as well as the overall inflation rate.

A.W. Phillips was one of the first economists to present compelling evidence of the inverse relationship between unemployment and wage inflation. Phillips studied the relationship between unemployment and the rate of change of wages in the United Kingdom over a period of almost a full century (from 1861 to 1957), and he discovered that the latter could be explained by two things: the level of unemployment and the rate of change of unemployment.

Phillips hypothesized that when demand for labor is high and there are few unemployed workers, employers can be expected to bid wages up quite rapidly; however, when demand for labor is low, and unemployment is high, workers are reluctant to accept lower wages than the prevailing rate, and as a result, wage rates fall very slowly.

The Federal Reserve Bank of the U.S. targets an inflation rate of 2%.

A second factor that affects wage rate changes is the rate of change in unemployment. If the economy is booming, employers will bid more vigorously for workers—which means that demand for labor is increasing at a fast pace (i.e., the percentage of unemployment is decreasing rapidly)—than they would if the demand for labor were either not increasing (e.g., percentage unemployment is unchanging) or only increasing at a slow pace.

Since wages and salaries are major input costs for companies, rising wages should lead to higher prices for products and services in an economy, ultimately pushing the overall inflation rate higher. As a result, Phillips graphed the relationship between general price inflation and unemployment, rather than wage inflation. The graph is known today as the Phillips Curve.

Low inflation and full employment are the cornerstones of monetary policy for the modern central bank. For instance, the U.S. Federal Reserve's monetary policy objectives are maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.

The tradeoff between inflation and unemployment led economists to use the Phillips Curve to fine-tune monetary or fiscal policy. Since a Phillips Curve for a specific economy would show an explicit level of inflation for a specific rate of unemployment and vice versa, it should be possible to aim for a balance between desired levels of inflation and unemployment.

The rate of change of the Consumer Price Index or CPI is the rate of inflation or an indicator of rising prices in the U.S. economy.

Figure 1 shows the rate of change of the CPI and unemployment rates in the 1960s.

If unemployment was 6%—and through monetary and fiscal stimulus , the rate was lowered to 5%—the impact on inflation would be negligible. In other words, with a 1% fall in unemployment, prices would not rise by much.

If instead, unemployment fell to 4% from 6%, we can see on the left axis that the corresponding inflation rate would rise to 3% from 1%.

Figure 1: U.S. inflation (CPI) and unemployment rates in the 1960s

Monetarist Rebuttal

The 1960s provided compelling proof of the validity of the Phillips Curve, such that a lower unemployment rate could be maintained indefinitely as long as a higher inflation rate could be tolerated.

However, in the late 1960s, a group of economists who were staunch monetarists , led by Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps , argued that the Phillips Curve does not apply over the long term. They contended that over the long run, the economy tends to revert to the natural rate of unemployment as it adjusts to any rate of inflation.

The natural rate is the long-term unemployment rate that is observed once the effect of short-term cyclical factors has dissipated and wages have adjusted to a level where supply and demand in the labor market are balanced. If workers expect prices to rise, they will demand higher wages so that their real (inflation-adjusted) wages are constant.

In a scenario wherein monetary or fiscal policies are adopted to lower unemployment below the natural rate, the resultant increase in demand will encourage firms and producers to raise prices even faster.

The U.S. unemployment rate as of Aug. 2023.

As inflation accelerates, workers may supply labor in the short term because of higher wages—leading to a decline in the unemployment rate; however, over the long haul, when workers are fully aware of the loss of their purchasing power in an inflationary environment, their willingness to supply labor diminishes and the unemployment rate rises to the natural rate. However, wage inflation and general price inflation continue to rise.

Therefore, over the duration, higher inflation would not benefit the economy through a lower rate of unemployment. By the same token, a lower rate of inflation should not inflict a cost on the economy through a higher rate of unemployment. Since inflation has no impact on the unemployment rate in the long term, the long-run Phillips curve morphs into a vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment.

Friedman's and Phelps's findings gave rise to the distinction between the short-run and long-run Phillips curves. The short-run Phillips curve includes expected inflation as a determinant of the current rate of inflation and hence is known by the formidable moniker "expectations-augmented Phillips Curve."

The natural rate of unemployment is not a static number but changes over time due to the influence of a number of factors. These include the impact of technology, changes in minimum wages, and the degree of unionization. In the U.S., the natural rate of unemployment was at 5.3% in 1949; it rose steadily until it peaked at 6.2% in 1978-79, and then declined afterward. It is expected to be around 4.5% for the remainder of the 2020 decade.

The monetarists' viewpoint did not gain much traction initially as it was made when the popularity of the Phillips Curve was at its peak. However, unlike the data from the 1960s, which definitively supported the Phillips Curve premise, the 1970s provided significant confirmation of Friedman's and Phelps' theory.

In fact, the data at many points over the next three decades do not provide clear evidence of the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation.

The 1970s were a period of both high inflation and high unemployment in the U.S. due to two massive oil supply shocks. The first oil shock was from the 1973 embargo by Middle East energy producers that caused crude oil prices to quadruple in about a year.

The second oil shock occurred when the Shah of Iran was overthrown in a revolution and the loss of output from Iran caused crude oil prices to double between 1979 and 1980. This development led to both high unemployment and high inflation.

The boom years of the 1990s were a time of low inflation and low unemployment. Economists attribute a number of reasons for this positive confluence of circumstances. These include:

- The global competition that kept a lid on price increases by U.S. producers

- Reduced expectations of future inflation as tight monetary policies had led to declining inflation for more than a decade

- Productivity improvements due to the large-scale adoption of technology

- Demographic changes in the labor force, with more aging baby boomers and fewer teens working

In the graphs below, we can see the inverse correlation between inflation—as measured by the rate of change of the CPI—and unemployment reassert itself, only to break down at times.

- In 2001, the mild recession as a result of 9/11 pushed unemployment higher to roughly 6% while inflation fell below 2.5%.

- In the mid-2000s, as unemployment fell, inflation was steady around 1% to 2.5%.

- During the Great Recession , the rate of change of the CPI fell dramatically as unemployment soared to almost 10%.

- From 2012 to 2015, we can see that the inverse correlation broke down where inflation and unemployment moved in tandem.

- From 2016 to 2019, unemployment steadily declined to 50-year lows (before the onset of COVID-19 at the end of 2019), while inflation remained around 2%. In other words, the inverse correlation between the two indicators wasn't as strong as it was in prior years.

- In 2020, unemployment soared to almost 15% (in April 2020) as a result of the economic impacts of the global pandemic caused by COVID-19 but decreased steadily through Jan. 2021.

- In Jan. 2021, the unemployment rate fell by 0.4 percentage points, to 6.3%. Although this measure is lower than the high reached in April 2020, it remained well above pre-pandemic levels (3.5%) in Feb. 2020. During this time, inflation remained relatively unaffected, although prices began to rise sharply starting in Feb. of 2021. These price rises were primarily due to the simultaneous supply shocks to the global economy, although likely increased as a result of the shortage of labor in essential industries.

- In 2022, inflation continued to soar and unemployment continued to drop, until reaching a stable level of approximately 3.5%, where it remained for the rest of 2022 and most of 2023. In the middle of 2022, inflation started to slow after the Fed's interest rate hikes.

Before the Covid pandemic and the ensuing high inflationary environment, an unusual feature of today's economic environment has been the paltry wage gains despite high corporate profits and declining unemployment since the Great Recession.

- In the first graph below, the annual percentage change in wages (red dotted line) for the private sector has barely nudged higher since 2015.

- In the second graph below, you can see that once the economy was hit with high inflation in 2022, constant dollar wages and salaries significantly dropped. They started to climb in 2022, but have not been raised enough to match pre-inflationary levels.

What Are the Main Causes of Unemployment?

There are many causes for unemployment, including general seasonal and cyclical factors, recessions, depressions, technological advancements replacing workers, and job outsourcing.

Does Inflation Lead to a Recession?

Inflation can lead to a recession. If prices are too high due to inflation and wages have not increased accordingly, this can cause consumers to slow down or stop spending. When this happens, businesses start to lose money, which would lead to them laying off employees, increasing unemployment, and increasing the number of people willing to spend less money, repeating the cycle and further slowing the economy.

Who Benefits From Inflation?

Generally, debtors benefit from inflation because they are repaying their loans with money that is less valuable than the money they borrowed initially. Banks can also benefit from inflation because when inflation is high, central banks increase interest rates to combat inflation. Banks make more money with higher interest rates.

The inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment depicted in the Phillips Curve works well in the short run, especially when inflation is fairly constant as it was in the 1960s. It does not hold up over the long term since the economy reverts to the natural rate of unemployment as it adjusts to any rate of inflation.

Because it's also more complicated than it appears at first glance, the relationship between inflation and unemployment has broken down in periods like the stagflationary 1970s and the booming 1990s.

International Monetary Fund. " Unemployment: The Curse of Joblessness ."

Economic Policy Institute. " Causes of Wage Stagnation ."

Economic Policy Institute. " A Long Spell of Very Low Unemployment Would Raise Wages—Even in the Face of Employers’ Monopsony Power ."

University of Miami. " The Phillips Curve ," Page 56.

Brookings Institution. " The Hutchins Center Explains: The Phillips Curve ."

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. " Why Does the Federal Reserve Aim for Inflation of 2% Over the Longer Run? "

Wiley Online Library. " The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957 ."

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. " The Federal Reserve's "Dual Mandate": The Evolution of an Idea ."

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. " Consumer Price Index ."

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. " The Employment Situation ."

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. " Dr. Econ, What Is the Relevance of the Phillips Curve to Modern Economies? "

The Nobel Prize. " Edmund S. Phelps ."

St. Louis Fed, FRED. " Noncyclical Rate of Unemployment ."

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. " The Natural Rate of Unemployment Over the Past 100 Years ."

Encyclopedia Brittanica. " Arab Oil Embargo ."

Brookings Institution. " What Iran’s 1979 Revolution Meant for US and Global Oil Markets ."

Yale University. " The Oil Shocks of the 1970s ."

University of Richmond. " Low Inflation: The Surprise of the 1990s ," Page 9.

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. " The 1990s Inflation Puzzle ," Page 9.

University of Richmond. " Low Inflation: The Surprise of the 1990s ," Pages 5-7.

University of Chicago. " Why Is the U.S. Unemployment Rate So Much Lower ?" Pages 1-2.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. " Job Market Remains Tight in 2019, as the Unemployment Rate Falls to its Lowest Level Since 1969 ."

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. " Consumer Price Index: 2020 in Review ."

St. Louis Fed, FRED. " Unemployment Rate ."

St. Louis Fed, FRED. " Unemployment Rate vs. Consumer Price Index ."

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Employment Cost Index ," Page 2.

- What Is Unemployment? Causes, Types, and Measurement 1 of 43

- What Does Termination of Employment Mean? 2 of 43

- What Is an Unemployment Claim? 3 of 43

- Unemployment Compensation: Definition, Requirements, and Example 4 of 43

- What Is Severance Pay? Definition and Why It's Offered 5 of 43

- Severance Package Explained: The Layoff Payoff 6 of 43

- 7 Considerations When You Negotiate Severance 7 of 43

- 7 Effective Ways to Prepare for a Layoff 8 of 43

- Unemployment Insurance (UI): How It Works, Requirements, and Funding 9 of 43

- How to Apply for Unemployment Insurance Now 10 of 43

- Who Doesn't Get Unemployment Insurance? 11 of 43

- What Was Private Unemployment Insurance? 12 of 43

- How to Pay Your Bills When You Lose Your Job 13 of 43

- Can I Access Money in My 401(k) If I Am Unemployed? 14 of 43

- All About COBRA Health Insurance 15 of 43

- Medical Debt: What to Do When You Can’t Pay 16 of 43

- Help, My Unemployment Benefits Are Running Out 17 of 43

- What Is the Unemployment Rate? Rates by State 18 of 43

- How Is the U.S. Monthly Unemployment Rate Calculated? 19 of 43

- Unemployment Rates: The Highest and Lowest Worldwide 20 of 43

- What You Need to Know About the Employment Report 21 of 43

- U-3 vs. U-6 Unemployment Rate: What's the Difference? 22 of 43

- Participation Rate vs. Unemployment Rate: What's the Difference? 23 of 43

- What the Unemployment Rate Does Not Tell Us 24 of 43

- How the Unemployment Rate Affects Everybody 25 of 43

- How Inflation and Unemployment Are Related 26 of 43

- How the Minimum Wage Impacts Unemployment 27 of 43

- The Cost of Unemployment to the Economy 28 of 43

- Okun’s Law: Economic Growth and Unemployment 29 of 43

- What Can Policymakers Do To Decrease Cyclical Unemployment? 30 of 43

- What Happens When Inflation and Unemployment Are Positively Correlated? 31 of 43

- The Downside of Low Unemployment 32 of 43

- Frictional vs. Structural Unemployment: What’s the Difference? 33 of 43

- Structural vs. Cyclical Unemployment: What's the Difference? 34 of 43

- Cyclical Unemployment: Definition, Cause, Types, and Example 35 of 43

- Disguised Unemployment: Definition and Different Types 36 of 43

- Employment-to-Population Ratio: Definition and What It Measures 37 of 43

- Frictional Unemployment: Definition, Causes, and Quit Rate Explained 38 of 43

- Full Employment: Definition, Types, and Examples 39 of 43

- Labor Force Participation Rate: Purpose, Formula, and Trends 40 of 43

- Labor Market Explained: Theories and Who Is Included 41 of 43

- What Is the Natural Unemployment Rate? 42 of 43

- Structural Unemployment: Definition, Causes, and Examples 43 of 43

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Philips-Curve-V3-7eb591d5e5174452b921fd88677c1229.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Page One Economics ®

Exploring the dynamics of unemployment.

"Unemployment is of vital importance, particularly to the unemployed."

—Edward Heath

Introduction

Think of some reasons people become unemployed. Did you think of someone quitting, getting fired, or being laid off? Well, all of those reasons are correct; and, if the people who experience any of those events actively seek new work, they're considered unemployed and part of the labor market. But it's not just those who quit, are fired, or are laid off who enter the labor market. Some enter the market for the first time, and some get back into it after being out for some time.

This article provides Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Population Survey (CPS) data on when people

- enter the labor market for the first time (new entrants),

- return to the market after being out for a while (re-entrants),

- choose to quit for a different job (job leavers), and

- lose their job and decide to find another one (job losers).

Each dataset provides information about labor market and economic conditions. We'll explore these unemployed groups and how they may behave differently over time and during recessions, which are typically associated with an increase in the overall unemployment rate.

Unemployment and the Business Cycle

Let's start with some basics. Economists and agencies such as the BLS define unemployment as a condition where people at least 16 years of age are without jobs and actively seeking work. Notice there are two conditions (besides age): The person is (1) without work and (2) looking for work.

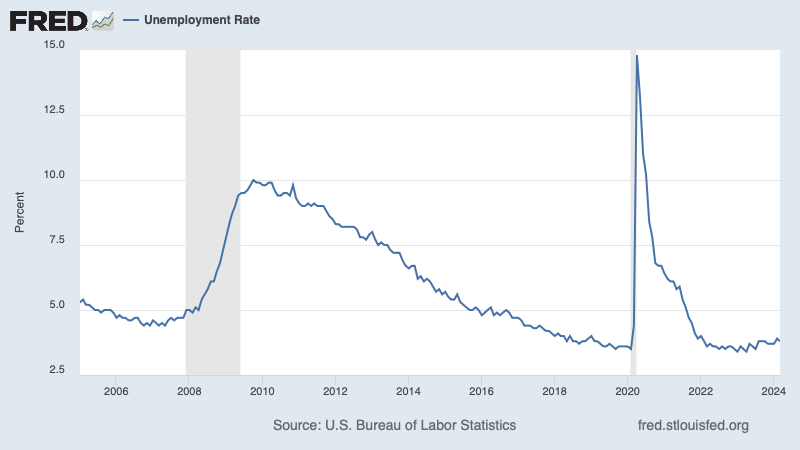

Figure 1 Unemployment Rate

SOURCE: US Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVuT .

Figure 1 shows the unemployment rate between 2005 and 2024. Each shaded area of the graph represents a recession (a contractionary phase of the business cycle ). 1 Note that the overall unemployment rate tends to be sensitive to business cycles. When the economy is contracting, such as during the Great Recession of 2008-09, fewer people are employed (an increase in the unemployment rate). Economists associate cyclical unemployment with recessions in the business cycle. When the economy is expanding, more people are employed (a decrease in the unemployment rate). Economists associate frictional unemployment with these times; unemployed people tend to be either new entrants to the labor market (such as recent graduates) or re-entrants (returning to the labor market after being out for a while).

The graph shows the unemployment rate overall, but the number of new entrants, re-entrants, job leavers, and job losers changes depending on economic conditions; how much they change tells us how sensitive each group is to the business cycle—cyclical sensitivity.

Entering the Labor Market

Everyone's journey through the labor market starts somewhere. More specifically, it starts with your first job. New entrants have never worked before and are entering the labor force for the first time. 2 They are mainly students transitioning from education to employment. When new entrants begin their job search, they don't have a job (yet) but are officially looking for work, so they count as unemployed (frictionally unemployed). New entrants make up around 10% of the total unemployed.

However, new job seekers aren't the only ones jumping into the labor market; re-entrants previously worked but were out of the labor force before searching for another job. Re-entering the labor market is a personal and economic decision.

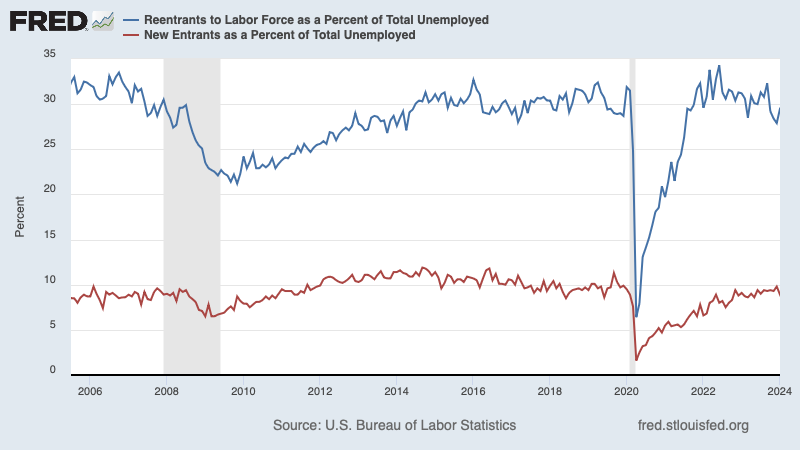

Re-entrants and New Entrants as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVvt .

Re-entrant unemployment is cyclically sensitive (Figure 2, blue line). 3 When compared with new entrants (red line), re-entrants make up a more significant percentage of the total unemployed, 4 particularly when there is economic expansion. As the economy expands, the percentage of re-entrants slowly increases because there is increased confidence the labor market is more favorable for job seekers. Conversely, as the economy contracts (such as during the 2008-09 and 2020 recessions), the proportion of re-entrants decreases significantly because they end their job searches, leaving the labor market.

Leaving the Labor Market Voluntarily

Job leavers voluntarily quit their job and look for new work. 5 We also call these instances voluntary separations or voluntary layoffs. Job leavers can provide information about how people feel about the labor market's strength. For example, in the post-pandemic recovery of 2021-23, factors like re-evaluation of work-life balance and a tight labor market led to an increased number of job leavers, as they were seeking higher-paying jobs or new opportunities. So, an increase in the number of job leavers can indicate a healthy labor market: It shows that workers are confident about their chances of finding a new job and that they'll voluntarily leave their current job.

Job Leavers as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVvY .

Figure 3 shows job leavers as a percent of the total unemployed from 2005 to January 2024. During recessions, such as the Great Recession of 2008-09, the percentage of job leavers declines, as fewer people leave their jobs due to uncertainty about finding new ones; this is driven by decreased business investment and demand for hires. Conversely, in economic expansions, more job leavers emerge as confidence grows, businesses invest more, and hiring increases. For example, as the economy recovered after the Great Recession (expansionary phase), the percentage of job leavers climbed upward and started to exceed pre-recession levels until the 2020 pandemic. 6 In September 2022, the percentage of job leavers peaked at 16%, and in October 2023 it returned to a pre-pandemic level of 12.3%, indicating the conclusion of what was headlined the "Great Resignation" or "Great Reshuffle." 7 The percentage of unemployed job leavers is still relatively small, and the percentage change among this group is the smallest throughout business cycles, indicating minimal cyclical sensitivity.

Leaving the Labor Market In voluntarily

Job losers are either temporarily laid off from a job but expect to be recalled or permanently laid off or fired from a job and begin looking for new work. We also call these instances involuntary separations or involuntary layoffs. Job losers have been particularly interesting to analyze because they make up the largest single group of the unemployed. 8

Job Losers as a Percent of Total Unemployed

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1jVwg .

Figure 4 shows job losers as a percent of the total unemployed from October 2005 to January 2024. The recessions in 2008-09 and 2020 show that the change in the percentage of job losers was reactive to each economic downturn. During the Great Recession it increased; after the recession ended in June 2009 the labor market recovery was slow, with the percentage of job losers ultimately returning to pre-recession levels in March 2015. 9 With a substantial period of economic expansion in the following years, the percentage of job losers decreased.

Each recession affects some industries more than others. During the 2020 recession, workers in the leisure and hospitality industry were the hardest hit. 10 This is an example of why job losers are the most cyclically sensitive of the four unemployed groups: As much as 70% of total business costs are employees. 11 During recessions, when businesses are dealing with decreased revenues, they look to cut their numbers of employees, investing less in labor.

Why does this information matter? Maybe you have been part of one of these unemployed groups or know someone who experienced unemployment, either voluntarily or involuntarily. When people experience unemployment, there is a reaction among each group, and how each group reacts plays a role in defining what the labor market looks and feels like for the unemployed, employed, and businesses. How cyclically sensitive each group is can also provide valuable insights for policymakers to make the best decisions for the economy and for businesses to recover after a downturn or continue to grow at a healthy rate.

1 The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee maintains a chronology of U.S. business cycles, which identifies the dates of peaks and troughs that frame economic recessions and expansions. A recession is the period between a peak of economic activity and its subsequent trough, or lowest point. Between trough and peak, the economy is in an expansion. Expansion is the normal state of the economy; most recessions are brief. However, the time it takes for the economy to return to its previous peak level of activity, or its previous trend path, may be quite extended. According to the NBER chronology, the most recent peak occurred in February 2020; the most recent trough occurred in April 2020. See https://www.nber.org/research/business-cycle-dating/business-cycle-dating-procedure-frequently-asked-questions .

2 U.S. Census Bureau. "Current Population Survey: Design and Methodology." Technical Paper 66, October 2006; https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/methodology/tp-66.pdf .

3 Gilroy, Curtis L. and McIntire, Robert J. "Job Losers, Leavers, and Entrants: A Cyclical Analysis." JSTOR Monthly Labor Review , November 1974, 97 (11), pp. 35-9; http://www.jstor.org/stable/41839192 . Accessed March 7, 2024.

4 Note that during the COVID recession, new-entrant unemployment seems to be equally sensitive (in terms of percentage drop).

5 U.S. Census Bureau, 2006. (See footnote 2.)

6 Lambert, Thomas E. "The Great Resignation in the United States: A Study of Labor Market Segmentation." Taylor & Francis Journals Forum for Social Economics , 2023, 52 (4), pp. 373-86; https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2022.2164599 .

7 See https://www.investopedia.com/the-great-resignation-is-officially-over-7963266#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways,have%20weighed%20down%20the%20economy .

8 Gilroy and McIntire, 1974. (See footnote 3.)

9 Weinberg, John. "The Great Recession and Its Aftermath." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Federal Reserve History, 2013; https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-and-its-aftermath .

10 See https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/#:~:text=No%20matter%20how%20you%20measure,remains%20as%20of%20February%202021 .

11 See https://www.bizjournals.com/bizjournals/news/2022/05/01/the-biggest-cost-of-doing-business.html .

© 2024, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Business cycle: The fluctuating levels of economic activity in an economy over a period of time measured from the beginning of one recession to the beginning of the next.

Cyclical unemployment: Unemployment associated with recessions in the business cycle.

Frictional unemployment: Unemployment that results when people are new to the job market (for example, recent graduates) or are transitioning from one job to another.

Unemployment rate: The percentage of the labor force that is willing and able to work, does not currently have a job, and is actively looking for employment.

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

The Effect of Quenching Temperature on the Structure and Properties of Alloy Ei437B-VD Blades for a Helicopter Gas Turbine Engine

- Published: 20 October 2016

- Volume 60 , pages 617–621, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- B. S. Lomberg 1 ,

- M. N. Letnikov 1 ,

- I. V. Kabanov 2 &

- A. N. Chelombit’ko 3

53 Accesses

Explore all metrics

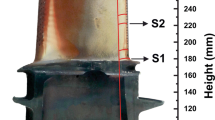

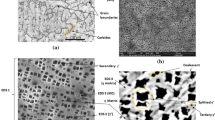

Results are given for a study of the effect of quenching temperature on macro- and microstructure, and mechanical properties of nickel-based superalloy EI437B-VD. It is shown that in order to improve structure stability and mechanical properties of rolled bar and stamped GTE blades made of alloy EI437B-VD, and also to avoid a different grain size, it is necessary to reduce quenching temperature in performing heat treatment from 1080 ± 5°C to 1020 ± 5°C.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Heat Transfer, Thermal Stress and Failure Inspection of a Gas Turbine Compressor Stator Blade Made of Five Different Conventional Superalloys and Ultra-High-Temperature Ceramic Material: A Direct Numerical Investigation

Relationship Between γ′ Phase Degradation and In-Service GTD-111 First-Stage Blade Local Temperature

The effect of the solution and aging treatments on the microstructures and microhardness of nickel-based superalloy

E. N. Kablov, “Innovative developments of FGUP VIAM GNTs RF for implementing “Strategic areas of material development and their processing technology for the period up to 2030,” Aviats. Mater. Tekhnol. , No. 1, 3–33 (2015).

E. N. Kablov, O. G. Ospennikova, B. S. Lomberg, and V. V. Sidorov, “Priority areas for developing manufacture of superalloys for aero engine building,” Probl. Chern. Met. Materialoved. , No. 3, 47–54 (2013).

E. N. Kablov, B. S. Lomberg, and O. G. Ospennikova, “Creation of contemporary superalloys and their manufacturing technology for aero engine building,” Krylya Rodiny , No. 3–4, 34–38 (2012).

B. S. Lomberg, S. V. Ovsepyan, and M. M. Bakradze, “Features of alloying and heat treatment of superalloys for disks for a new generation of gas-turbine engines,” Aviats. Mater. Tekhnol. , No. 2, 3–8 (2010).

B. S. Lomberg, S. V. Ovsepyan, M. M. Bakradze, and I. S. Mazalov, “High-temperature nickel superalloys for gas turbine engine components,” Aviats. Mater. Technol. , Spec. Iss. (2012).

G. S. Garibov, N. M. Grits, V. P. Shmelev, et al., Patent 2455383 RF, IPC C22F1/10, “Heat treatment method for nickel-base superalloys in order to improve low-cycle fatigue resistance,” subm. 05.05.2011, publ. 07.10.2012.

S. V. Ovsepyan, B. S. Lomberg, M. M. Bakradze, and N. M. Letnikov, “Heat treatment of wrought nickel-base superalloys for GTE disks,” Vestn. MGTU im Baumana. Ser. Mashinostr. , No. SP2, 122–130 (2011).

M. M. Bakradze, S. V. Ovsepyan, S. A. Shugaev, and M. N. Letnikov, “Effect of quenching regimes on structure and properties of nickel-base superalloy EK151-ID disk stampings,” Trudy VIAM , No. 9, Art. 01 (2013).

B. S. Lomberg, M. M. Bakradze, E. B. Chabina, and E. V. Filonova, “Correlation of structure and properties for nickel-base superalloys for gas turbine disks,” Aviats. Mater. Tekhnol. , No. 2, 25–30 (2011).

E. V. Filonova, M. M. Bakradze, A. Ya. Kochubei, and N. A. Vavilin, “Study of changes in structure and phase composition of alloy VZh175 during hot deformation and heat treatment,” Aviats. Mater. Tekhnol. , No. 3, 10–13 (2014).

Patent 2019150 (A1) EP, “Method of controlling and refining final grain size in supersolvus heat treated nickel-base superalloy,” subm. 06.28.2007, publ. 01.01.2009.

Patent 8679269 US, “Method of controlling grain size in forget precipitation-strengthened alloys and components formed thereby,” subm. 05.05.2011, publ. 11.08.2012.

Patent 7553384 US, “Local heat treatment for improved fatigue resistance in turbine components,” subm. 01.25.2006, publ. 06.30.2009.

Patent 2176436 EP, “A method of heat treating a superalloy component and an alloy component,” subm. 08.03.2007, publ. 04.21.2010.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

State Research Center of the Russian Federation – All-Russia Research Institute of Aviation Materials (VIAM), Moscow, Russia

B. S. Lomberg & M. N. Letnikov

Elektrostal Metallurgical Plant, Elektrostal, Moscow Region, Russia

I. V. Kabanov

Motor Sich Company, Zaporozhie, Ukraine

A. N. Chelombit’ko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to B. S. Lomberg .

Additional information

Translated from Metallurg, No. 6, pp. 68–72, June, 2016.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lomberg, B.S., Letnikov, M.N., Kabanov, I.V. et al. The Effect of Quenching Temperature on the Structure and Properties of Alloy Ei437B-VD Blades for a Helicopter Gas Turbine Engine. Metallurgist 60 , 617–621 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-016-0340-5

Download citation

Received : 04 February 2015

Published : 20 October 2016

Issue Date : September 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-016-0340-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- microstructure

- different grain size

- mechanical properties

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This paper estimates the short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment for the Indian economy over the period 2009-2015, in order to know whether there is a tradeoff between inflation and ...

In this paper, local projections are used to explore the unemployment-price inflation relationship in a more generalized, empirical fashion. We find that inflation's reaction to changes in the unemployment rate varies across states of the economy, with timing as the primary difference. In low-unemployment environments, inflation reacts immediately and persistently. In high-unemployment ...

The parameter λ2 (s) is depicted for inflation, λ21 (s), and unemployment, λ22 (s), in Figure 2. It is seen that λ21 (s) is large at all scales, whereas λ22 (s) is large at scales smaller than one year. Large values of λ21 (s) imply that rare events occurring in the inflation rate make its PDF non-Gaussian.

The theory of the Phillips curve (Phillips 1958; The University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2011), a diagrammatic representation of the economic relationship between inflation and unemployment, explains why we consider inflation and unemployment without regard to nominal (or real) interest rates in the two-equation theory of partial ...

The discussion over the relationship between the inflation, unemployment and economic growth has been relevant over the centuries to a wide range of economic interests. It is agreed among the researchers and economists that reaching the price stability, ceteris paribus, will have a beneficial effect on employment and economic prosperity measured with GDP growth, particularly under the ...

The inflation and unemployment rates consistently show negative relationships with financial satisfaction, whereas the real GDP growth rate shows a positive relationship. For instance, in 2010-2014, when the inflation and unemployment rates increased by one percentage point, the financial satisfaction score fell by 0.052 units and 0.018 units ...

The purpose of this paper is to continue research on the Phillips curve and to examine the relationship between inflation and unemployment for 2 The use of the reciprocal form suggests that a small increase in the unemployment rate would be associated with a much larger decrease in the excess demand for labor at low unemployment rates.

The empirical findings from the XWT method suggest a relationship between unemployment, inflation, and GDP, though the relationship varies over time and frequency. ... Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. ... The relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment ...

The 'natural rate of unemployment' was not an important part of Friedman's presidential address, although it is what the paper is remembered for. On the 50th anniversary of the paper, we argue that there is no 'natural rate of unemployment', and that the relation between inflation and unemployment is not the one assumed by Friedman or ...

In his original paper, Phillips tracked wage changes and unemployment changes in Great Britain from 1861 to 1957, and found that there was a stable, inverse relationship between wages and unemployment. ... The relationship between inflation rates and unemployment rates is inverse. Graphically, this means the short-run Phillips curve is L-shaped ...

relationship between unemployment and inflation rates. These variables are highly connected, Phillips maintained "that much more detailed research into the relations between unemployment, wage rates, prices and productivity" was needed. Then, Okun posited there is a negative relationship between output and unemployment (Knotek 2007).

Key Takeaways. Inflation and unemployment typically have an inverse correlation but the relationship is a complex one. In times of high unemployment, wages typically remain stagnant, and wage ...

examine the unidirectional relationship between unemployment, economic growth, and inflation in North African states between 1965 and 2016. [7].

The Phillips Curve explains the inverse relationship between unemployment rates and inflation rates. Okun's law supports the link between the economy's unemployment rates and its total output. ... has its mean at 4.87 and totals 765 observations. Another critical variable in this paper, the inflation rate, has its variation range from −9.73% ...

The study explores the relationship between unemployment and inflation as indicated by the existing and prevalent situations and circumstances in the Philippine economy. The two economic indicators are explored and discussed to be able to show how they affect the quality of life of Filipinos belonging to various sectors and social status.

The empirical study method is time series analysis, and the monthly data set covers the period from January 1992 to April 2023. According to the study's findings, no causality relationship could be detected between unemployment and inflation variables in Germany in the period, neither in the long run nor in the short run.

This article empirically analyzes the relationship between unemployment rate and inflation rate in the Philippines over the period 1980-2006. The negative association between unemployment and inflation is known as the Phillips Curve because the trade-off relationship between these two variables was first pointed out by William Phillips in 1958. Since then, the Phillips Curve has remained an ...

The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between inflation, unemployment, exchange ... An Empirical Analysis of the Nexus Between Inflation, Exchange Rate, Unemployment and Economic Growth in Ethiopia: A Granger Casualty Approach - Ferede Mengistie Alemu, 2024