Honors Theses

What this handout is about.

Writing a senior honors thesis, or any major research essay, can seem daunting at first. A thesis requires a reflective, multi-stage writing process. This handout will walk you through those stages. It is targeted at students in the humanities and social sciences, since their theses tend to involve more writing than projects in the hard sciences. Yet all thesis writers may find the organizational strategies helpful.

Introduction

What is an honors thesis.

That depends quite a bit on your field of study. However, all honors theses have at least two things in common:

- They are based on students’ original research.

- They take the form of a written manuscript, which presents the findings of that research. In the humanities, theses average 50-75 pages in length and consist of two or more chapters. In the social sciences, the manuscript may be shorter, depending on whether the project involves more quantitative than qualitative research. In the hard sciences, the manuscript may be shorter still, often taking the form of a sophisticated laboratory report.

Who can write an honors thesis?

In general, students who are at the end of their junior year, have an overall 3.2 GPA, and meet their departmental requirements can write a senior thesis. For information about your eligibility, contact:

- UNC Honors Program

- Your departmental administrators of undergraduate studies/honors

Why write an honors thesis?

Satisfy your intellectual curiosity This is the most compelling reason to write a thesis. Whether it’s the short stories of Flannery O’Connor or the challenges of urban poverty, you’ve studied topics in college that really piqued your interest. Now’s your chance to follow your passions, explore further, and contribute some original ideas and research in your field.

Develop transferable skills Whether you choose to stay in your field of study or not, the process of developing and crafting a feasible research project will hone skills that will serve you well in almost any future job. After all, most jobs require some form of problem solving and oral and written communication. Writing an honors thesis requires that you:

- ask smart questions

- acquire the investigative instincts needed to find answers

- navigate libraries, laboratories, archives, databases, and other research venues

- develop the flexibility to redirect your research if your initial plan flops

- master the art of time management

- hone your argumentation skills

- organize a lengthy piece of writing

- polish your oral communication skills by presenting and defending your project to faculty and peers

Work closely with faculty mentors At large research universities like Carolina, you’ve likely taken classes where you barely got to know your instructor. Writing a thesis offers the opportunity to work one-on-one with a with faculty adviser. Such mentors can enrich your intellectual development and later serve as invaluable references for graduate school and employment.

Open windows into future professions An honors thesis will give you a taste of what it’s like to do research in your field. Even if you’re a sociology major, you may not really know what it’s like to be a sociologist. Writing a sociology thesis would open a window into that world. It also might help you decide whether to pursue that field in graduate school or in your future career.

How do you write an honors thesis?

Get an idea of what’s expected.

It’s a good idea to review some of the honors theses other students have submitted to get a sense of what an honors thesis might look like and what kinds of things might be appropriate topics. Look for examples from the previous year in the Carolina Digital Repository. You may also be able to find past theses collected in your major department or at the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library. Pay special attention to theses written by students who share your major.

Choose a topic

Ideally, you should start thinking about topics early in your junior year, so you can begin your research and writing quickly during your senior year. (Many departments require that you submit a proposal for an honors thesis project during the spring of your junior year.)

How should you choose a topic?

- Read widely in the fields that interest you. Make a habit of browsing professional journals to survey the “hot” areas of research and to familiarize yourself with your field’s stylistic conventions. (You’ll find the most recent issues of the major professional journals in the periodicals reading room on the first floor of Davis Library).

- Set up appointments to talk with faculty in your field. This is a good idea, since you’ll eventually need to select an advisor and a second reader. Faculty also can help you start narrowing down potential topics.

- Look at honors theses from the past. The North Carolina Collection in Wilson Library holds UNC honors theses. To get a sense of the typical scope of a thesis, take a look at a sampling from your field.

What makes a good topic?

- It’s fascinating. Above all, choose something that grips your imagination. If you don’t, the chances are good that you’ll struggle to finish.

- It’s doable. Even if a topic interests you, it won’t work out unless you have access to the materials you need to research it. Also be sure that your topic is narrow enough. Let’s take an example: Say you’re interested in the efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s and early 1980s. That’s a big topic that probably can’t be adequately covered in a single thesis. You need to find a case study within that larger topic. For example, maybe you’re particularly interested in the states that did not ratify the ERA. Of those states, perhaps you’ll select North Carolina, since you’ll have ready access to local research materials. And maybe you want to focus primarily on the ERA’s opponents. Beyond that, maybe you’re particularly interested in female opponents of the ERA. Now you’ve got a much more manageable topic: Women in North Carolina Who Opposed the ERA in the 1970s and 1980s.

- It contains a question. There’s a big difference between having a topic and having a guiding research question. Taking the above topic, perhaps your main question is: Why did some women in North Carolina oppose the ERA? You will, of course, generate other questions: Who were the most outspoken opponents? White women? Middle-class women? How did they oppose the ERA? Public protests? Legislative petitions? etc. etc. Yet it’s good to start with a guiding question that will focus your research.

Goal-setting and time management

The senior year is an exceptionally busy time for college students. In addition to the usual load of courses and jobs, seniors have the daunting task of applying for jobs and/or graduate school. These demands are angst producing and time consuming If that scenario sounds familiar, don’t panic! Do start strategizing about how to make a time for your thesis. You may need to take a lighter course load or eliminate extracurricular activities. Even if the thesis is the only thing on your plate, you still need to make a systematic schedule for yourself. Most departments require that you take a class that guides you through the honors project, so deadlines likely will be set for you. Still, you should set your own goals for meeting those deadlines. Here are a few suggestions for goal setting and time management:

Start early. Keep in mind that many departments will require that you turn in your thesis sometime in early April, so don’t count on having the entire spring semester to finish your work. Ideally, you’ll start the research process the semester or summer before your senior year so that the writing process can begin early in the fall. Some goal-setting will be done for you if you are taking a required class that guides you through the honors project. But any substantive research project requires a clear timetable.

Set clear goals in making a timetable. Find out the final deadline for turning in your project to your department. Working backwards from that deadline, figure out how much time you can allow for the various stages of production.

Here is a sample timetable. Use it, however, with two caveats in mind:

- The timetable for your thesis might look very different depending on your departmental requirements.

- You may not wish to proceed through these stages in a linear fashion. You may want to revise chapter one before you write chapter two. Or you might want to write your introduction last, not first. This sample is designed simply to help you start thinking about how to customize your own schedule.

Sample timetable

Avoid falling into the trap of procrastination. Once you’ve set goals for yourself, stick to them! For some tips on how to do this, see our handout on procrastination .

Consistent production

It’s a good idea to try to squeeze in a bit of thesis work every day—even if it’s just fifteen minutes of journaling or brainstorming about your topic. Or maybe you’ll spend that fifteen minutes taking notes on a book. The important thing is to accomplish a bit of active production (i.e., putting words on paper) for your thesis every day. That way, you develop good writing habits that will help you keep your project moving forward.

Make yourself accountable to someone other than yourself

Since most of you will be taking a required thesis seminar, you will have deadlines. Yet you might want to form a writing group or enlist a peer reader, some person or people who can help you stick to your goals. Moreover, if your advisor encourages you to work mostly independently, don’t be afraid to ask them to set up periodic meetings at which you’ll turn in installments of your project.

Brainstorming and freewriting

One of the biggest challenges of a lengthy writing project is keeping the creative juices flowing. Here’s where freewriting can help. Try keeping a small notebook handy where you jot down stray ideas that pop into your head. Or schedule time to freewrite. You may find that such exercises “free” you up to articulate your argument and generate new ideas. Here are some questions to stimulate freewriting.

Questions for basic brainstorming at the beginning of your project:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- Why do I care about this topic?

- Why is this topic important to people other than myself

- What more do I want to learn about this topic?

- What is the main question that I am trying to answer?

- Where can I look for additional information?

- Who is my audience and how can I reach them?

- How will my work inform my larger field of study?

- What’s the main goal of my research project?

Questions for reflection throughout your project:

- What’s my main argument? How has it changed since I began the project?

- What’s the most important evidence that I have in support of my “big point”?

- What questions do my sources not answer?

- How does my case study inform or challenge my field writ large?

- Does my project reinforce or contradict noted scholars in my field? How?

- What is the most surprising finding of my research?

- What is the most frustrating part of this project?

- What is the most rewarding part of this project?

- What will be my work’s most important contribution?

Research and note-taking

In conducting research, you will need to find both primary sources (“firsthand” sources that come directly from the period/events/people you are studying) and secondary sources (“secondhand” sources that are filtered through the interpretations of experts in your field.) The nature of your research will vary tremendously, depending on what field you’re in. For some general suggestions on finding sources, consult the UNC Libraries tutorials . Whatever the exact nature of the research you’re conducting, you’ll be taking lots of notes and should reflect critically on how you do that. Too often it’s assumed that the research phase of a project involves very little substantive writing (i.e., writing that involves thinking). We sit down with our research materials and plunder them for basic facts and useful quotations. That mechanical type of information-recording is important. But a more thoughtful type of writing and analytical thinking is also essential at this stage. Some general guidelines for note-taking:

First of all, develop a research system. There are lots of ways to take and organize your notes. Whether you choose to use note cards, computer databases, or notebooks, follow two cardinal rules:

- Make careful distinctions between direct quotations and your paraphrasing! This is critical if you want to be sure to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work. For more on this, see our handout on plagiarism .

- Record full citations for each source. Don’t get lazy here! It will be far more difficult to find the proper citation later than to write it down now.

Keeping those rules in mind, here’s a template for the types of information that your note cards/legal pad sheets/computer files should include for each of your sources:

Abbreviated subject heading: Include two or three words to remind you of what this sources is about (this shorthand categorization is essential for the later sorting of your sources).

Complete bibliographic citation:

- author, title, publisher, copyright date, and page numbers for published works

- box and folder numbers and document descriptions for archival sources

- complete web page title, author, address, and date accessed for online sources

Notes on facts, quotations, and arguments: Depending on the type of source you’re using, the content of your notes will vary. If, for example, you’re using US Census data, then you’ll mainly be writing down statistics and numbers. If you’re looking at someone else’s diary, you might jot down a number of quotations that illustrate the subject’s feelings and perspectives. If you’re looking at a secondary source, you’ll want to make note not just of factual information provided by the author but also of their key arguments.

Your interpretation of the source: This is the most important part of note-taking. Don’t just record facts. Go ahead and take a stab at interpreting them. As historians Jacques Barzun and Henry F. Graff insist, “A note is a thought.” So what do these thoughts entail? Ask yourself questions about the context and significance of each source.

Interpreting the context of a source:

- Who wrote/created the source?

- When, and under what circumstances, was it written/created?

- Why was it written/created? What was the agenda behind the source?

- How was it written/created?

- If using a secondary source: How does it speak to other scholarship in the field?

Interpreting the significance of a source:

- How does this source answer (or complicate) my guiding research questions?

- Does it pose new questions for my project? What are they?

- Does it challenge my fundamental argument? If so, how?

- Given the source’s context, how reliable is it?

You don’t need to answer all of these questions for each source, but you should set a goal of engaging in at least one or two sentences of thoughtful, interpretative writing for each source. If you do so, you’ll make much easier the next task that awaits you: drafting.

The dread of drafting

Why do we often dread drafting? We dread drafting because it requires synthesis, one of the more difficult forms of thinking and interpretation. If you’ve been free-writing and taking thoughtful notes during the research phase of your project, then the drafting should be far less painful. Here are some tips on how to get started:

Sort your “evidence” or research into analytical categories:

- Some people file note cards into categories.

- The technologically-oriented among us take notes using computer database programs that have built-in sorting mechanisms.

- Others cut and paste evidence into detailed outlines on their computer.

- Still others stack books, notes, and photocopies into topically-arranged piles.There is not a single right way, but this step—in some form or fashion—is essential!

If you’ve been forcing yourself to put subject headings on your notes as you go along, you’ll have generated a number of important analytical categories. Now, you need to refine those categories and sort your evidence. Everyone has a different “sorting style.”

Formulate working arguments for your entire thesis and individual chapters. Once you’ve sorted your evidence, you need to spend some time thinking about your project’s “big picture.” You need to be able to answer two questions in specific terms:

- What is the overall argument of my thesis?

- What are the sub-arguments of each chapter and how do they relate to my main argument?

Keep in mind that “working arguments” may change after you start writing. But a senior thesis is big and potentially unwieldy. If you leave this business of argument to chance, you may end up with a tangle of ideas. See our handout on arguments and handout on thesis statements for some general advice on formulating arguments.

Divide your thesis into manageable chunks. The surest road to frustration at this stage is getting obsessed with the big picture. What? Didn’t we just say that you needed to focus on the big picture? Yes, by all means, yes. You do need to focus on the big picture in order to get a conceptual handle on your project, but you also need to break your thesis down into manageable chunks of writing. For example, take a small stack of note cards and flesh them out on paper. Or write through one point on a chapter outline. Those small bits of prose will add up quickly.

Just start! Even if it’s not at the beginning. Are you having trouble writing those first few pages of your chapter? Sometimes the introduction is the toughest place to start. You should have a rough idea of your overall argument before you begin writing one of the main chapters, but you might find it easier to start writing in the middle of a chapter of somewhere other than word one. Grab hold where you evidence is strongest and your ideas are clearest.

Keep up the momentum! Assuming the first draft won’t be your last draft, try to get your thoughts on paper without spending too much time fussing over minor stylistic concerns. At the drafting stage, it’s all about getting those ideas on paper. Once that task is done, you can turn your attention to revising.

Peter Elbow, in Writing With Power, suggests that writing is difficult because it requires two conflicting tasks: creating and criticizing. While these two tasks are intimately intertwined, the drafting stage focuses on creating, while revising requires criticizing. If you leave your revising to the last minute, then you’ve left out a crucial stage of the writing process. See our handout for some general tips on revising . The challenges of revising an honors thesis may include:

Juggling feedback from multiple readers

A senior thesis may mark the first time that you have had to juggle feedback from a wide range of readers:

- your adviser

- a second (and sometimes third) faculty reader

- the professor and students in your honors thesis seminar

You may feel overwhelmed by the prospect of incorporating all this advice. Keep in mind that some advice is better than others. You will probably want to take most seriously the advice of your adviser since they carry the most weight in giving your project a stamp of approval. But sometimes your adviser may give you more advice than you can digest. If so, don’t be afraid to approach them—in a polite and cooperative spirit, of course—and ask for some help in prioritizing that advice. See our handout for some tips on getting and receiving feedback .

Refining your argument

It’s especially easy in writing a lengthy work to lose sight of your main ideas. So spend some time after you’ve drafted to go back and clarify your overall argument and the individual chapter arguments and make sure they match the evidence you present.

Organizing and reorganizing

Again, in writing a 50-75 page thesis, things can get jumbled. You may find it particularly helpful to make a “reverse outline” of each of your chapters. That will help you to see the big sections in your work and move things around so there’s a logical flow of ideas. See our handout on organization for more organizational suggestions and tips on making a reverse outline

Plugging in holes in your evidence

It’s unlikely that you anticipated everything you needed to look up before you drafted your thesis. Save some time at the revising stage to plug in the holes in your research. Make sure that you have both primary and secondary evidence to support and contextualize your main ideas.

Saving time for the small stuff

Even though your argument, evidence, and organization are most important, leave plenty of time to polish your prose. At this point, you’ve spent a very long time on your thesis. Don’t let minor blemishes (misspellings and incorrect grammar) distract your readers!

Formatting and final touches

You’re almost done! You’ve researched, drafted, and revised your thesis; now you need to take care of those pesky little formatting matters. An honors thesis should replicate—on a smaller scale—the appearance of a dissertation or master’s thesis. So, you need to include the “trappings” of a formal piece of academic work. For specific questions on formatting matters, check with your department to see if it has a style guide that you should use. For general formatting guidelines, consult the Graduate School’s Guide to Dissertations and Theses . Keeping in mind the caveat that you should always check with your department first about its stylistic guidelines, here’s a brief overview of the final “finishing touches” that you’ll need to put on your honors thesis:

- Honors Thesis

- Name of Department

- University of North Carolina

- These parts of the thesis will vary in format depending on whether your discipline uses MLA, APA, CBE, or Chicago (also known in its shortened version as Turabian) style. Whichever style you’re using, stick to the rules and be consistent. It might be helpful to buy an appropriate style guide. Or consult the UNC LibrariesYear Citations/footnotes and works cited/reference pages citation tutorial

- In addition, in the bottom left corner, you need to leave space for your adviser and faculty readers to sign their names. For example:

Approved by: _____________________

Adviser: Prof. Jane Doe

- This is not a required component of an honors thesis. However, if you want to thank particular librarians, archivists, interviewees, and advisers, here’s the place to do it. You should include an acknowledgments page if you received a grant from the university or an outside agency that supported your research. It’s a good idea to acknowledge folks who helped you with a major project, but do not feel the need to go overboard with copious and flowery expressions of gratitude. You can—and should—always write additional thank-you notes to people who gave you assistance.

- Formatted much like the table of contents.

- You’ll need to save this until the end, because it needs to reflect your final pagination. Once you’ve made all changes to the body of the thesis, then type up your table of contents with the titles of each section aligned on the left and the page numbers on which those sections begin flush right.

- Each page of your thesis needs a number, although not all page numbers are displayed. All pages that precede the first page of the main text (i.e., your introduction or chapter one) are numbered with small roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv, v, etc.). All pages thereafter use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

- Your text should be double spaced (except, in some cases, long excerpts of quoted material), in a 12 point font and a standard font style (e.g., Times New Roman). An honors thesis isn’t the place to experiment with funky fonts—they won’t enhance your work, they’ll only distract your readers.

- In general, leave a one-inch inch margin on all sides. However, for the copy of your thesis that will be bound by the library, you need to leave a 1.25-inch margin on the left.

How do I defend my honors thesis?

Graciously, enthusiastically, and confidently. The term defense is scary and misleading—it conjures up images of a military exercise or an athletic maneuver. An academic defense ideally shouldn’t be a combative scene but a congenial conversation about the work’s merits and weaknesses. That said, the defense probably won’t be like the average conversation that you have with your friends. You’ll be the center of attention. And you may get some challenging questions. Thus, it’s a good idea to spend some time preparing yourself. First of all, you’ll want to prepare 5-10 minutes of opening comments. Here’s a good time to preempt some criticisms by frankly acknowledging what you think your work’s greatest strengths and weaknesses are. Then you may be asked some typical questions:

- What is the main argument of your thesis?

- How does it fit in with the work of Ms. Famous Scholar?

- Have you read the work of Mr. Important Author?

NOTE: Don’t get too flustered if you haven’t! Most scholars have their favorite authors and books and may bring one or more of them up, even if the person or book is only tangentially related to the topic at hand. Should you get this question, answer honestly and simply jot down the title or the author’s name for future reference. No one expects you to have read everything that’s out there.

- Why did you choose this particular case study to explore your topic?

- If you were to expand this project in graduate school, how would you do so?

Should you get some biting criticism of your work, try not to get defensive. Yes, this is a defense, but you’ll probably only fan the flames if you lose your cool. Keep in mind that all academic work has flaws or weaknesses, and you can be sure that your professors have received criticisms of their own work. It’s part of the academic enterprise. Accept criticism graciously and learn from it. If you receive criticism that is unfair, stand up for yourself confidently, but in a good spirit. Above all, try to have fun! A defense is a rare opportunity to have eminent scholars in your field focus on YOU and your ideas and work. And the defense marks the end of a long and arduous journey. You have every right to be proud of your accomplishments!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Atchity, Kenneth. 1986. A Writer’s Time: A Guide to the Creative Process from Vision Through Revision . New York: W.W. Norton.

Barzun, Jacques, and Henry F. Graff. 2012. The Modern Researcher , 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Graff, Gerald, and Cathy Birkenstein. 2014. “They Say/I Say”: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . New York: Pantheon.

Lasch, Christopher. 2002. Plain Style: A Guide to Written English. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Ten things I wish I'd known before starting my dissertation

The sun is shining but many students won't see the daylight. Because it's that time of year again – dissertation time.

Luckily for me, my D-Day (dissertation hand-in day) has already been and gone. But I remember it well.

The 10,000-word spiral-bound paper squatted on my desk in various forms of completion was my Allied forces; the history department in-tray was my Normandy. And when Eisenhower talked about a "great crusade toward which we have striven these many months", he was bang on.

I remember first encountering the Undergraduate Dissertation Handbook, feeling my heart sink at how long the massive file took to download, and began to think about possible (but in hindsight, wildly over-ambitious) topics. Here's what I've learned since, and wish I'd known back then…

1 ) If your dissertation supervisor isn't right, change. Mine was brilliant. If you don't feel like they're giving you the right advice, request to swap to someone else – providing it's early on and your reason is valid, your department shouldn't have a problem with it. In my experience, it doesn't matter too much whether they're an expert on your topic. What counts is whether they're approachable, reliable, reassuring, give detailed feedback and don't mind the odd panicked email. They are your lifeline and your best chance of success.

2 ) If you mention working on your dissertation to family, friends or near-strangers, they will ask you what it's about, and they will be expecting a more impressive answer than you can give. So prepare for looks of confusion and disappointment. People anticipate grandeur in history dissertation topics – war, genocide, the formation of modern society. They don't think much of researching an obscure piece of 1970s disability legislation. But they're not the ones marking it.

3 ) If they ask follow-up questions, they're probably just being polite.

4 ) Do not ask friends how much work they've done. You'll end up paranoid – or they will. Either way, you don't have time for it.

5 ) There will be one day during the process when you will freak out, doubt your entire thesis and decide to start again from scratch. You might even come up with a new question and start working on it, depending on how long the breakdown lasts. You will at some point run out of steam and collapse in an exhausted, tear-stained heap. But unless there are serious flaws in your work (unlikely) and your supervisor recommends starting again (highly unlikely), don't do it. It's just panic, it'll pass.

6 ) A lot of the work you do will not make it into your dissertation. The first few days in archives, I felt like everything I was unearthing was a gem, and when I sat down to write, it seemed as if it was all gold. But a brutal editing down to the word count has left much of that early material at the wayside.

7 ) You will print like you have never printed before. If you're using a university or library printer, it will start to affect your weekly budget in a big way. If you're printing from your room, "paper jam" will come to be the most dreaded two words in the English language.

8 ) Your dissertation will interfere with whatever else you have going on – a social life, sporting commitments, societies, other essay demands. Don't even try and give up biscuits for Lent, they'll basically become their own food group when you're too busy to cook and desperate for sugar.

9 ) Your time is not your own. Even if you're super-organised, plan your time down to the last hour and don't have a single moment of deadline panic, you'll still find that thoughts of your dissertation will creep up on you when you least expect it. You'll fall asleep thinking about it, dream about it and wake up thinking about. You'll feel guilty when you're not working on it, and mired in self-doubt when you are.

10 ) Finishing it will be one of the best things you've ever done. It's worth the hard work to know you've completed what's likely to be your biggest, most important, single piece of work. Be proud of it.

- Blogging students

- Higher education

- Advice for students

Most viewed

Writing an Honors Thesis

An Honors Thesis is a substantial piece of independent research that an undergraduate carries out over two semesters. Students writing Honors Theses take PHIL 691H and 692H, in two different semesters. What follows answers all the most common questions about Honors Theses in Philosophy.

All necessary forms are fillable and downloadable.

Honors Thesis Application

Honors Thesis Contract

Honors Thesis Learning Contract

Who can write an Honors Thesis in Philosophy?

Any Philosophy major who has a total, cumulative GPA of at least 3.3 and a GPA of at least 3.5 (with a maximum of one course with a PS grade) among their PHIL courses can in principle write an Honors Thesis. In addition, students need to satisfy a set of specific pre-requisites, as outlined below.

What are the pre-requisites for an Honors Thesis in Philosophy?

The requirements for writing an Honors Thesis in Philosophy include

- having taken at least five PHIL courses, including two numbered higher than 299;

- having a total PHIL GPA of at least 3.5 (with a maximum of one course with a PS grade); and

- having done one of the following four things:

- taken and passed PHIL 397;

- successfully completed an Honors Contract associated with a PHIL course;

- received an A or A- in a 300-level course in the same area of philosophy as the proposed thesis ; or

- taken and passed a 400-level course in the same area of philosophy as the proposed thesis .

When should I get started?

You should get started with the application process and search for a prospective advisor the semester before you plan to start writing your thesis – that is, the semester before the one in which you want to take PHIL 691H.

Often, though not always, PHIL 691H and 692H are taken in the fall and spring semesters of the senior year, respectively. It is also possible to start earlier and take 691H in the spring semester of the junior year and PHIL 692H in the fall of the senior year. Starting earlier has some important advantages. One is that it means you will finish your thesis in time to use it as a writing sample, should you decide to apply to graduate school. Another is that it avoids a mad rush near the very end of your last semester.

How do I get started?

Step 1: fill out the honors thesis application.

The first thing you need to do is fill out an Honors Thesis Application and submit it to the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) for their approval.

Step 2: Find an Honors Thesis Advisor with the help of the DUS

Once you have been approved to write an Honors Thesis, you will consult with the DUS about the project that you have in mind and about which faculty member would be an appropriate advisor for your thesis. It is recommended that you reach out informally to prospective advisors to talk about their availability and interest in your project ahead of time, and that you include those suggestions in your application, but it is not until your application has been approved that the DUS will officially invite the faculty member of your choice to serve as your advisor. You will be included in this correspondence and will receive written confirmation from your prospective advisor.

Agreeing to be the advisor for an Honors Thesis is a major commitment, so bear in mind that there is a real possibility that someone asked to be your advisor will say no. Unfortunately, if we cannot find an advisor, you cannot write an Honors Thesis.

Step 3: Fill out the required paperwork needed to register for PHIL 691H

Finally, preferably one or two weeks before the start of classes (or as soon as you have secured the commitment of a faculty advisor), you need to fill out an Honors Thesis Contract and an Honors Thesis Learning Contract , get them both signed by your advisor, and email them to the DUS.

Once the DUS approves both of these forms, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 691H. All of this should take place no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner).

What happens when I take PHIL 691H and PHIL 692H?

PHIL 691H and PHIL 692H are the course numbers that you sign up for to get credit for working on an Honors Thesis. These classes have official meeting times and places. In the case of PHIL 691H , those are a mere formality: You will meet with your advisor at times you both agree upon. But in the case of PHIL 692H , they are not a mere formality: The class will actually meet as a group, at least for the first few weeks of the semester (please see below).

When you take PHIL 691H, you should meet with your advisor during the first 5 days of classes and, if you have not done so already, fill out an Honors Thesis Learning Contract and turn in to the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) . This Contract will serve as your course syllabus and must be turned in and approved no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner). Once the DUS approves your Honors Thesis Learning Contract, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 691H.

Over the course of the semester, you will meet regularly with your advisor. By the last day of classes, you must turn in a 10-page paper on your thesis topic; this can turn out to be part of your final thesis, but it doesn’t have to. In order to continue working on an Honors Thesis the following semester, this paper must show promise of your ability to complete one, in the opinion of your advisor. Your advisor should assign you a grade of “ SP ” at the conclusion of the semester, signifying “satisfactory progress” (so you can move on to PHIL 692H). Please see page 3 of this document for more information.

When you take PHIL 692H, you’ll still need to work with your advisor to fill out an Honors Thesis Learning Contract . This Contract will serve as your course syllabus and must be turned in to and approved by the DUS no later than the 5th day of classes in any given semester (preferably sooner).

Once the DUS approves your Honors Thesis Learning Contract, they’ll get you registered for PHIL 692H.

At the end of the second semester of senior honors thesis work (PHIL 692H), your advisor should assign you a permanent letter grade. Your advisor should also change your PHIL 691H grade from “ SP ” to a permanent letter grade. Please see page 3 of this document for more information.

The Graduate Course Option

If you and your advisor agree, you may exercise the Graduate Course Option. If you do this, then during the semester when you are enrolled in either PHIL 691H or PHIL 692H, you will attend and do the work for a graduate level PHIL course. (You won’t be officially enrolled in that course.) A paper you write for this course will be the basis for your Honors Thesis. If you exercise this option, then you will be excused from the other requirements of the thesis course (either 691H or 692H) that you are taking that semester.

Who can be my advisor?

Any faculty member on a longer-than-one-year contract in the Department of Philosophy may serve as your honors thesis advisor. You will eventually form a committee of three professors, of which one can be from outside the Department. But your advisor must have an appointment in the Philosophy Department. Graduate Students are not eligible to advise Honors Theses.

Who should be my advisor?

Any faculty member on a longer-than-one-year contract in the Department of Philosophy may serve as your honors thesis advisor. It makes most sense to ask a professor who already knows you from having had you as a student in a class. In some cases, though, this is either not possible, or else there is someone on the faculty who is an expert on the topic you want to write about, but from whom you have not taken a class. Information about which faculty members are especially qualified to advise thesis projects in particular areas of philosophy can be found here .

What about the defense?

You and your advisor should compose a committee of three professors (including the advisor) who will examine you and your thesis. Once the committee is composed, you will need to schedule an oral examination, a.k.a. a defense. You should take the initiative here, communicating with all members of your committee in an effort to find a block of time (a little over an hour) when all three of you can meet. The thesis must be defended by a deadline , set by Honors Carolina , which is usually a couple of weeks before the end of classes. Students are required to upload the final version of their thesis to the Carolina Digital Repository by the final day of class in the semester in which they complete the thesis course work and thesis defense.

What is an Honors Thesis in Philosophy like?

An Honors Thesis in Philosophy is a piece of writing in the same genre as a typical philosophy journal article. There is no specific length requirement, but 30 pages (double-spaced) is a good guideline. Some examples of successfully defended Honors The easiest way to find theses of past philosophy students is on the web in the Carolina Digital Repository . Some older, hard copies of theses are located on the bookshelf in suite 107 of Caldwell Hall. (You may ask the Director of Undergraduate Studies (DUS) , or anyone else who happens to be handy, to show you where it is!)

How does the Honors Thesis get evaluated?

The honors thesis committee will evaluate the quality and originality of your thesis as well as of your defense and then decides between the following three options:

- they may award only course credit for the thesis work if the thesis is of acceptable quality;

- they may designate that the student graduate with honors if the thesis is of a very strong quality;

- they may recommend that the student graduate with highest honors if the thesis is of exceptional quality.

As a matter of best practice, our philosophy department requires that examining committees refer all candidates for highest honors to our Undergraduate Committee chaired by the Director of Undergraduate Studies. This committee evaluates nominated projects and makes the final decision on awarding highest honors. Highest honors should be awarded only to students who have met the most rigorous standards of scholarly excellence.

Office of Undergraduate Education

University Honors Program

- Honors Requirements

- Major and Thesis Requirements

- Courses & Experiences

- Nova Series

- Honors Courses

- NEXUS Experiences

- Non-Course Experiences

- Faculty-Directed Research and Creative Projects

- Community Engagement and Volunteering

- Internships

- Learning Abroad

Honors Thesis Guide

- Sample Timeline

- Important Dates and Deadlines

- Requirements and Evaluation Criteria

- Supervision and Approval

- Credit and Honors Experiences

- Style and Formatting

- Submit Your Thesis

- Submit to the Digital Conservancy

- Honors Advising

- Honors Reporting Center

- Get Involved

- University Honors Student Association

- UHSA Executive Board

- Honors Multicultural Network

- Honors Mentor Program

- Honors Community & Housing

- Freshman Invitation

- Post-Freshman Admission

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Faculty Fellows

- Faculty Resources

- Honors Faculty Representatives

- Internal Honors Scholarships

- Office for National and International Scholarships

- Letters of Recommendation

- Personal Statements

- Scholarship Information

- Honors Lecture Series

- Honors Recognition Ceremony

- Make a Donation

- UHP Land Acknowledgment

- UHP Policies

An honors thesis is required of all students graduating with any level of Latin honors. It is an excellent opportunity for undergraduates to define and investigate a topic in depth, and to complete an extended written reflection of their results & understanding. The work leading to the thesis is excellent preparation for graduate & professional school or the workplace.

- Sample timeline

- Requirements and evaluation criteria

- Supervision and approval

- Style and formatting

- Submitting your thesis

- Submitting to the Digital Conservancy

Thesis Database

The thesis database is a searchable collection of over 6,000 theses, with direct access to more than 4,000 full-text theses in PDF format. The database—fully searchable by discipline, keyword, level of Latin Honors, and more—is available for student use in the UHP Office, 8am–4:30pm, Monday–Friday.

Thesis Forms & Documents

- Thesis Title Page template

- Thesis work is reported using the "Thesis Proposal" and "Thesis Completion" WorkflowGen processes found in the Honors Reporting Center.

- Summer Research Opportunities

- Global Seminars and LAC Seminars

- Honors Research in London - Summer 2024

Global Ecology @ Flinders

10 things I wish I knew before doing an Honours degree

In 2018 I started my Honours degree in biodiversity and conservation at Flinders University. I had completed my Bachelor of Science in 2017, after being accepted in the Honours stream through my Year 12 Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR).

I will not sugar-coat it — I was a bad Bachelor student. I scarcely attended classes and at times submitted sub-par work. I believed that as long as I didn’t fail anything I would still be able to do my Honours, so I did the bare minimum and just got by. However in the last semester I discovered I needed an average GPA of 5.0 to secure my Honours position, regardless of what stream I was doing. Panic ensued, I was already too deep in my final semester of not achieving to pull my grades around. Thankfully, I was eventually accepted, after having to plead my case with the Honours board.

In the end I managed to score myself a First Class Honours and a PhD candidature (and hopefully soon a publication). Honours was definitely a struggle, but it was also one of the best experiences of my life. I just wish I had known these 10 things before I started …

1. You will fail

Not the brightest note to start on, but don’t fear, everyone fails. Honours is full of ups and downs, and at some point, somewhere along the line, something in your project will go wrong. But it’s okay! It happens to every person that has ever done an Honours or a PhD. Whether the failing is small or catastrophic, remember this happens all the time.

More importantly your supervisor or co-ordinator sees it all the time. The best thing to do is tell your supervisor and your co-ordinator early on. It may be a simple case of steering your research in a slightly new direction, changing the scope of your project, or even taking some extra time. It’s okay to fail, just keep pushing.

2. You will be treated differently

Again, not as bad as it sounds! One of the biggest things I noticed during my Honours was how much I was treated as a colleague instead of an (undergraduate) student. People will start asking your opinion on subjects, especially on your research. Take these opportunities to test your skills learned during the Bachelors; it’s a great way to build networks for your career. You will also be a representative of your lab or supervisor, so you may be sent to conferences or be asked to represent them at different events. Take this time to shine.

3. You will be independent

Being independent during your Honours is a tricky balance. On the one hand, you will need to be an independent thinker and problem-solver — this is the big leagues after all. But on the other, it is important to have a good working relationship with your supervisor(s). In my case, I would pre-plan the number of times I would attempt something or the amount of time I would allocate to trying to solve a problem relative to the size of work. I found that when I presented something to my supervisor, or was frustrated at something not working, they were more willing to help because I had attempted it myself first to the best of my abilities.

4. You’ll make great friends

Friends at uni are so important for the overall experience, but especially so in Honours. The cohorts are much smaller and so you get to know your peers on a personal level. This is beneficial for many reasons. First, they understand your struggle like no-one else (“how many words is your lit review?” “When are you going to start writing your thesis?” “What form is your thesis in?” “Want to get coffee?”). Study groups or even lunch-break groups ensure that you still have social connections and help with independent problem solving. These friends are also able to check up on you when you go MIA into a thesis-writing vortex. Basically, they get it.

5. You will develop a caffeine addiction and become anaemic

Okay, this one might be just me, but it is a cautionary tale. I know that the 6 th cup of coffee and the 2-minute noodles or mi goreng might seem like the best option for a meal at the end of what seems like a 72-hour day, but trust me, there are consequences. Make sure to take AT LEAST one day a week off your uni work. I called these days personal admin days, usually a Sunday.

Cook something nutritional, such as easily freezable meals (my personal favourites are soups — anything with beans and curries). You are not productive when you are sick and tired. Similar with caffeine. If you are staring down the barrel of your 5 th coffee or energy drink for the day, perhaps take a walk instead, or simply call it a day. And get a good feed and night’s rest and come back the next day ready to go.

6. You will have no time at the end of your thesis

Be prepared to have your life consumed by your thesis and research for the last few months (if you have no time during your whole Honours year, you might have to reassess your workload). Fear not, it should only be for the last few months of “crunch time” during the actual writing phase. In this time, be honest with your friends and family, let them know that you may not be able to attend everything because your thesis must take priority in this time. But it will all be over soon and they can go back to having your undivided attention.

7. At some point(s) you will hate your thesis

Have you ever heard of imposter syndrome? It is the feeling that you have accidently ended up where you are and that you are unqualified or not deserving of your success. It is something that I suffered for most of my Honours. This thought process made me hate my thesis at some points; I felt that it wasn’t good enough or that I had no right to be talking about my research.

But guess what? I didn’t get to where I was by accident. I worked hard (see opening paragraph). It is normal to hate your own work sometimes, but you have to work through it. Talk to your supervisor or peers, get them to re-read your work and help you with some constructive criticism or praise. It can sometimes also be beneficial to take some time away from writing your thesis: try formatting it, doing some other work, or just taking the day off to come back the next day and go again. Whatever you do, DO NOT FREAK OUT AND DELETE EVERYTHING — it is never as bad as you think.

8. People will listen to you

As I wrote above, you are not where you are by accident. You have worked hard to get where you are (repeat until you believe it). Guess what? You are now rapidly becoming an expert in your field. You have a Bachelors degree, you know (or should know) what you are talking about, and people (including your peers) are going to find your research interesting. You are now more a peer then a student yourself, so be confident and willing to share your knowledge. Remember that you stand on the shoulders of giants who have previously shared their knowledge with you. Pay it forward.

9. It’s actually great!

Yep, Honours is actually a really great experience, and something that I recommend to everyone thinking about it. I know that it can be daunting, because you often talk to Honours students while they’re in the midst of their writing, are sleep-deprived, and who are probably jacked-up on caffeine (see point 5). This is like asking a parent what it’s like being a parent when they have a three-year old who is in the throes of toilet training, has a fever, and has decided she no longer wants to sleep in her own bed. But I promise you, the skills, experience, networking and future opportunities far outweigh any of the negatives

10. You can do it

A positive note to end on! Yes, you can do it. It will be tough and you will struggle at times, but you can do it. Remember that your co-ordinator and more often than not, your supervisor, has been through this. Draw on their wealth of knowledge and keep good communication so they can help you if you are slipping or need to readjust your study load or research question.

Kathryn Venning

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: 10 things I wish I knew before doing an Honours degree | ConservationBytes.com

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Honors & Theses

The Honors Thesis: An opportunity to do innovative and in-depth research.

An honors thesis gives students the opportunity to conduct in-depth research into the areas of government that inspire them the most. Although, it’s not a requirement in the Department of Government, the honors thesis is both an academic challenge and a crowning achievement at Harvard. The faculty strongly encourages students to write an honors thesis and makes itself available as a resource to those students who do. Students work closely with the thesis advisor of their choice throughout the writing process. Approximately 30% of Government concentrators each year choose to write a thesis.

Guide to Writing a Senior Thesis in Government

You undoubtedly have many questions about what writing a thesis entails. We have answers for you. Please read A Guide to Writing a Senior Thesis in Government , which you can download as a PDF below. If you still have questions or concerns after you have read through this document, we encourage you to reach out to the Director of Undergraduate Studies, Dr. Nara Dillon ( [email protected] ), the Assistant Director of Undergraduate Studies, Dr. Gabriel Katsh ( [email protected] ), or the Undergraduate Program Manager, Karen Kaletka ( [email protected] ).

- Search UNH.edu

- Search University Honors Program

Commonly Searched Items:

- Hamel Scholars Program

- Honors Program Admission

- Registration & Advising

- Honors Requirements

- Honors Courses & Example Syllabi

- Honors in Discovery

- Interdisciplinary Honors

- Departmental Honors

Honors Thesis

- Graduating with Honors

- The Honors Community

- Scholarships and Awards

- Student Leadership Organizations

- Student FAQ

- Honors Advising

- Honors Outdoor Orientation Trips (HOOT)

- Faculty Recognition

- Faculty FAQ

- Faculty List

- Honors Staff

- Annual Report

- Honors Digest

- Fall 2024 Honors College

All Honors Students end their program with an Honors Thesis: a sustained, independent research project in a student’s field of study. Your thesis must count for at least 4 credits (some majors require that the thesis be completed over 2 semesters, and some require more than 4 credits). The thesis is an opportunity to work on unique research under the guidance of a faculty advisor. It often provides a writing sample for graduate school, and is also something you can share with employers to show what kind of work you can do.

What is an Honors thesis?

Most of your work in college involves learning information and ideas generated by other people. When you write a thesis, you are engaging with previous work, but also adding new knowledge to your field. That means you have to know what's already been done--what counts as established knowledge; what's the current state of research; what methods and kinds of evidence are acceptable; what debates are going on. (Usually, you'll recount that knowledge in a review of the literature.) Then, you need to form a research question that you can answer given your available skills, resources, and time (so, not "What is love?" but "How are ideas about love different between college freshmen and seniors?"). With your advisor, you'll plan the method you will use to answer it, which might involve lab work, field work, surveys, interviews, secondary research, textual analysis, or something else--it will depend upon your question and your field. Once your research is carried out, you'll write a substantial paper (usually 20-50 pages) according to the standards of your field.

What do theses look like?

The exact structure will vary by discipline, and your thesis advisor should provide you with an outline. As a rough guideline, we would expect to see something like the following:

1. Introduction 2. Review of the literature 3. Methods 4. Results 5. Analysis 6. Conclusion 7. Bibliography or works cited

In 2012 we began digitally archiving Honors theses. Students are encouraged to peruse the Honors Thesis Repository to see what past students' work has looked like. Use the link below and type your major in the search field on the left to find relevant examples. Older Honors theses are available in the Special Collections & Archives department at Dimond Library.

Browse Previous Theses

Will my thesis count as my capstone?

Most majors accept an Honors Thesis as fulfilling the Capstone requirement. However, there are exceptions. In some majors, the thesis counts as a major elective, and in a few, it is an elective that does not fulfill major requirements. Your major advisor and your Honors advisor can help you figure out how your thesis will count. Please note that while in many majors the thesis counts as the capstone, the converse does not necessarily apply. There are many capstone experiences that do not take the form of an Honors thesis.

Can I do a poster and presentation for my thesis?

No. While you do need to present your thesis (see below), a poster and presentation are not a thesis.

How do I choose my thesis advisor?

The best thesis advisor is an experienced researcher, familiar with disciplinary standards for research and writing, with expertise in your area of interest. You might connect with a thesis advisor during Honors-in-Major coursework, but Honors Liaisons can assist students who are having trouble identifying an advisor. You should approach and confirm your thesis advisor before the semester in which your research will begin.

What if I need funds for my research?

The Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research offers research grants, including summer support. During the academic year, students registered in credit-bearing thesis courses may apply for an Undergraduate Research Award for up to $600 in research expenses (no stipend). Students who are not otherwise registered in a credit-bearing course for their thesis research may enroll in INCO 790: Advanced Research Experience, which offers up to $200 for research expenses.

What if I need research materials for a lengthy period?

No problem! Honors Students can access Extended Time borrowing privileges at Dimond Library, which are otherwise reserved for faculty and graduate students. Email [email protected] with note requesting “extended borrowing privileges” and we'll work with the Library to extend your privileges.

Can I get support to stay on track?

Absolutely! Thesis-writers have an opportunity to join a support group during the challenging and sometimes isolating period of writing a thesis. Learn more about thesis support here .

When should I complete my thesis?

Register for a Senior Honors Thesis course (often numbered 799) in the spring and/or fall of your Senior year.

This “course” is an independent study, overseen by your Thesis Advisor. Your advisor sets the standards, due dates, and grades for your project. It must earn at least a B in order to qualify for Honors.

What happens with my completed thesis?

Present your thesis.

All students must publicly present their research prior to graduation. Many present at the Undergraduate Research Conference in April; other departmentally-approved public events are also acceptable.

Publish your thesis:

Honors students are asked to make their thesis papers available on scholars.unh.edu/honors/ . This creates a resource for future students and other researchers, and also helps students professionalize their online personas.

These theses are publicly available online. If a student or their advisor prefers not to make the work available, they may upload an abstract and/or excerpts from the work instead.

Students may also publish research in Inquiry , UNH's undergraduate research journal.

University Honors Program

- Honors withdrawal form

- Discovery Flex Option

- Honors Thesis Support Group

- Designating a Course as Honors

- Honors track registration

- Spring 2024 Honors Discovery Courses

- Honors Discovery Seminars

- Engagement Meet-Ups (EMUs)

- Sustainability

- Embrace New Hampshire

- University News

- The Future of UNH

- Campus Locations

- Calendars & Events

- Directories

- Facts & Figures

- Academic Advising

- Colleges & Schools

- Degrees & Programs

- Undeclared Students

- Course Search

- Academic Calendar

- Study Abroad

- Career Services

- How to Apply

- Visit Campus

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Graduate Admissions

- UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law

- Housing & Residential Life

- Clubs & Organizations

- New Student Programs

- Student Support

- Fitness & Recreation

- Student Union

- Health & Wellness

- Student Life Leadership

- Sport Clubs

- UNH Wildcats

- Intramural Sports

- Campus Recreation

- Centers & Institutes

- Undergraduate Research

- Research Office

- Graduate Research

- FindScholars@UNH

- Business Partnerships with UNH

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Research and Technology at UNH

- Request Information

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

HLTH432 Honours Thesis information guide

What is hlth432a/b honours thesis, why complete a thesis, who is eligible to enroll in hlth432a/b, contact potential supervisors, tips for the interview with your potential supervisor, external supervisors, complete hlth432a/b enrollment process, how am i graded in hlth432a/b.

According to the calendar course description, HLTH432 is:

“An independent research project on an approved topic, supervised by a faculty member. Includes an approved proposal and completion of -- introduction, review of literature, methods, data collection, data analysis and presentation of results in thesis form. Recommended for students planning graduate studies.”

Generally, an Honours thesis is a research project in which you choose a topic, review all relevant literature, collect and analyse data and then report your results. If there is an area of health sciences or public health that you find particularly interesting and if you feel that you understand statistics and research design, you may want to consider completing the honours thesis, which may require either Social Science (non-lab based) or a Biohealth (lab based) research. The research may involve:

- Original field or lab research (pending finances);

- Secondary analysis of existing data;

- Historical or archival analyses;

- Systematic Review or meta-analysis.

Back to top

The main objective of the Honours Thesis (HLTH 432A/HLTH 432B) is to provide you with an opportunity to gain experience in formulating and evaluating research ideas, but even more importantly, completing a thesis will allow you to consolidate your thinking about the many aspects of health you have studied during your undergraduate career.

How will that happen? You will:

- review, evaluate and interpret information from a wide range of relevant disciplines that are relevant to a specific area of health science / public health.

- integrate and apply that information to identify and address a specific health problem.

- consider the ethical issues specific to your research.

- apply your knowledge of methodologies, at least in one type of research.

- you will have the opportunity to polish your written communications, and

- in your meetings with your supervisor, you will have the chance to practice communicating your ideas orally in a one-on-one situation with a scientist-mentor; moreover,

- you will have the opportunity to enhance your information literacy skills and your data collection and analysis skills.

The thesis is an exciting way to cap off your undergraduate career. It provides huge opportunities for you to consolidate what you already know, and to learn about a specific topic in-depth. It also provides you with invaluable preparation for whatever path you take after your undergraduate studies. Finally, it is a really amazing experience to actually create new knowledge!

The following prerequisites apply:

- Department Consent Required: please submit HLTH432 Honours Thesis Pre-approval Application online.

- HLTH 204 or approved equivalent statistics course and HLTH 333; Level at least 4A School of Public Health Sciences (SPHS) students.

- Normally, minimum 75% major and overall averages are recommended to enrol in the course but 80% major and overall averages are preferred.

- A faculty member must agree to act as your supervisor. Because of limited faculty resources, enrolment in HLTH 432A/B is not guaranteed.

You will be notified via email once your HLTH432 Honours Thesis Pre-approval Application is approved. The email will also include a course outline for HLTH432. If you have received this material, you have indicated an interest in taking HLTH 432A and have received Department Consent. Your next step is to:

- Review this package completely.

- Create a WORD document (250 words or less) that provides details of any research or other relevant experience that a potential supervisor might be interested in knowing about you.

- Create a WORD document (250 words or less) that provides details of any specific research interests or research questions you might wish to investigate, including support for your questions (if you have considered the area in greater depth).

- Review and update your resume.

- Review the SPHS Faculty members’ areas of research interests and decide on one or two potential supervisors. If you already have a research question, try to select a potential supervisor whose area of interest is most closely related to that question. See the list of SPHS faculty members by area of focus .

- DO NOT approach faculty members without emailing first to make an appointment.

- If at all possible use your @uwaterloo.ca email. This email is less likely to end up in Junk mail.

Email template

Dear (Use proper title and full name),

I am writing to express interest in working on an honours thesis under your supervision. I have reviewed your research interests and would be very excited to work on an aspect of your research, or to develop independent research that is consistent with your work. I am attaching a recent resume, a statement of my experience and a statement of my research interests for you to review.

I am available on (state days of the week) at (state hours of availability) to see you. Would it be possible to book an appointment at any of those times? I look forward to meeting with you to discuss your research, and whether there is a way in which I can contribute to it with an honours thesis.

Yours truly, (your name) (contact email and telephone)

- Be punctual

- Be respectful

- Highlight any experience you have.

- Highlight your academic strengths

- your unofficial transcript

- your resume

- your statement of research interests and/or another sample of your written work

- the Thesis Requirements (Appendix A in the course outline) so that your potential supervisor can review the expectations for the thesis

- FORM 432A - Agreement to Supervise .

On occasion, students may be permitted to work with a supervisor from outside the School of Public Health Sciences. There are two separate categories of external supervisors:

- Category B supervisors are UW professors from other Departments in the Faculty of Health or are one of our adjunct faculty members. In such cases, the research thesis and the supervisor must be approved by the Associate Director of Undergraduate Studies, who is the coordinator of HLTH 432A/B. The thesis will be approved if it meets SPHS standards for learning objectives.

- Category C supervisors may be professors from another faculty at the University of Waterloo (e.g., Science, Arts), or the supervisor may be someone who conducts research outside the University of Waterloo. In such cases, the research thesis and the supervisor must be approved by the Associate Director, Undergraduate Studies, who coordinates HLTH 432A/B. The thesis will be approved if it meets SPHS standards for learning objectives and the HLTH 432A/B coordinator can arrange for an SPHS faculty member to co-supervise the thesis.

My supervisor has agreed! What’s next?

- Submit HLTH432 Honours Thesis Enrollment Form for HLTH432A online no later than one week prior to the last day to add courses for the school term . Note you will need to upload a signed copy of Form432A (PDF) in order to complete the online submission, so please allow plenty of time for yourself to gather your supervisor’s signature.

- At the end of your HLTH 432A term, you need to submit another HLTH432 Honours Thesis Enrollment Form for HLTH432B. You will not be enrolled in HLTH 432B until your supervisor has agreed to supervise you for a second semester. The procedure and deadline is similar to HLTH432A enrollment: the HLTH432 Honours Thesis Enrollment Form for HLTH432B needs to be received no later than one week prior to the last day to add courses for the school term . A signed copy of Form432B (PDF) will need to be uploaded at the same time to complete the online submission.

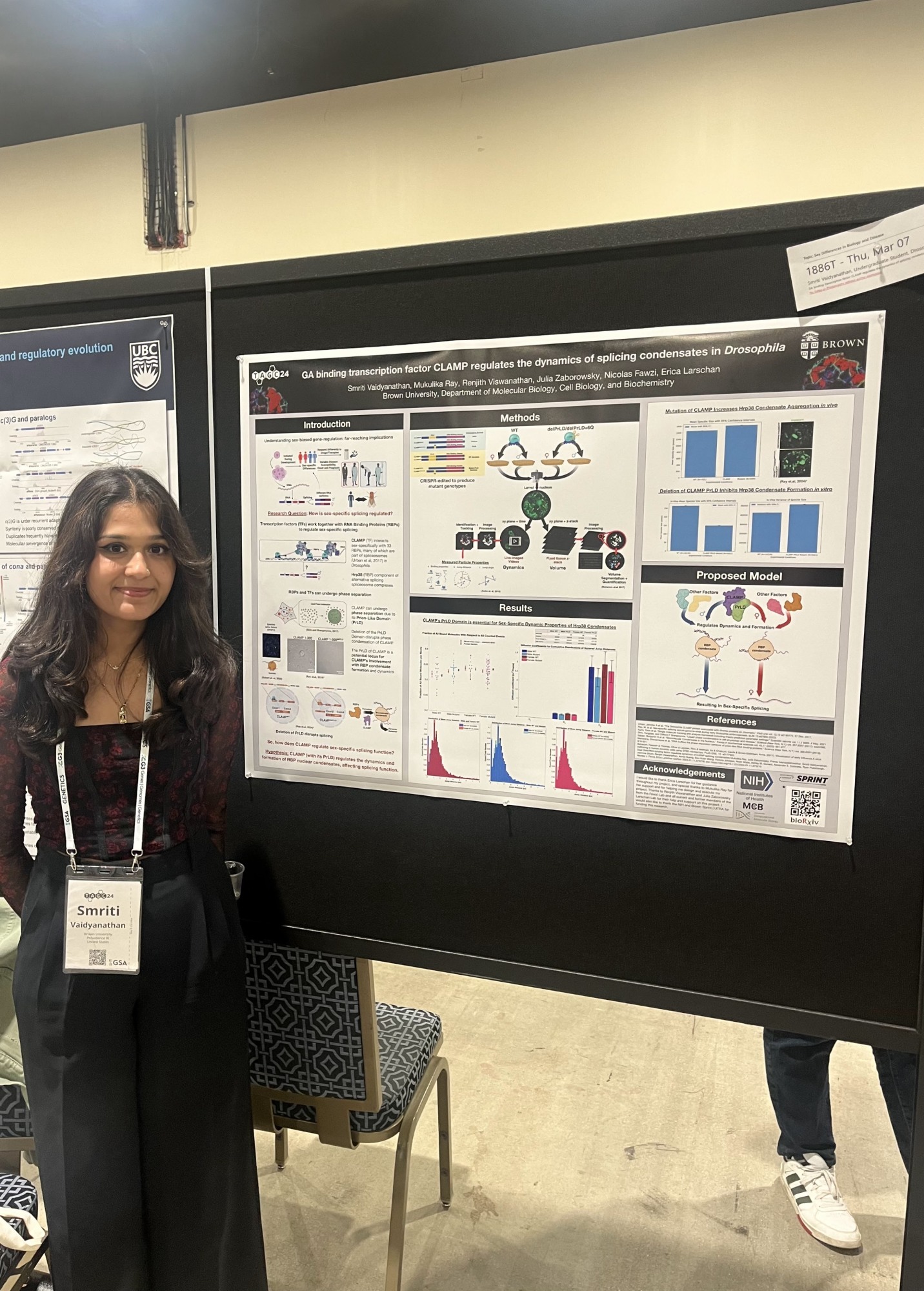

Separate grades are submitted for your work in 432A and 432B and the nature of the term products that will be evaluated will depend upon the type of thesis you are completing (Social Science/non-lab or Biohealth/lab –the course outline). Due dates for term products for each of 432A and 432B are specified in the course outline. Normally these are the final day of classes for the term in which you are enrolled in the course. Your supervisor must submit final grades to the Course Coordinator at the very latest by the end of the examination period, and you must submit your term products before this to give your supervisor time to read and grade it. A number of drafts should be submitted early so that your supervisor can read them and provide comments. This will allow for revisions to be made before the final submission of materials for grading. Remember to provide the Course Coordinator with a final copy of your thesis. Note that you will also have to give a poster presentation on your proposal towards the end of the HLTH 432A term and a Powerpoint presentation on your final thesis project during the 4 th year Honours Thesis Colloquium at the end of the HLTH 432B term.

WRITING AN HONORS THESIS IN THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT

Updated January 2022

Honors English students, following Schreyer Honors College requirements, compose a thesis of significant scholarly research or creative writing. The thesis is completed in close consultation with a thesis supervisor during the semester before the student’s graduation semester, while the student is enrolled in English 494H.

In the graduation semester, students polish and submit their theses for approval by the thesis supervisor and the honors advisor and then submit them to Schreyer Honors College. Dates of final submission vary; please consult your honors advisor and the Schreyer website .

An Honors Thesis in English

An English honors thesis in scholarly research and interpretation should be an ambitious, well-researched, in-depth study focused on a topic chosen by the student in consultation with the thesis supervisor.

An English honors thesis in creative writing should be a sophisticated and well-crafted creative project written in consultation with the thesis supervisor, a project that demonstrates the student’s increasing proficiency of their chosen creative genre(s).

The Critical/Literary Studies Thesis

A critical / literary studies thesis might arise from a range of possibilities: a course paper you would like to extend; an interest you were unable to pursue in class; a connection between two classes that you’ve made on your own; an author, set of works, or theme you want to explore in greater depth; a critical question that has been puzzling you; a body of literature that you want to contextualize; a topic relevant to post-graduate plans (e.g., law school, graduate school, marketing career, writing career, and so forth). Consider also your skill sets, your workload and experiences, and the timeline for completion. The questions you’re asking should be open to productive analysis, questions worth asking.

The topic should challenge you, so that you’re neither summarizing nor skimming the surface of the primary and secondary work under consideration. Chapters within the thesis should build upon each other and connect to an overarching theme or argument. The thesis should be as clear and concise as possible. Make sure the argument is structured, with each chapter and each paragraph having a clear role to play in the development of the argument.

Because the thesis is a scholarly product, it will demonstrate good research skills and effective use of secondary readings. It will also be grammatically correct. Your work will be entering existing critical conversations with other scholarship, so your research should be sufficiently completed prior to your finalizing the thesis plan. Your work should have properly formatted notes and bibliography, whether in Chicago, MLA, or APA style.

Note length stipulations: Honors theses in critical / literary studies may be as short as 8,000 words but no longer than 15,000 words. If the thesis is shorter or longer than these advised limits, explain your thinking and decision-making in the introduction of your thesis.

The Creative Thesis

The creative thesis will be an innovative, stylistically sophisticated work, attentive to language and voice. The work should develop a sustained narrative or theme. Most students who write creative theses produce a collection of short stories or personal essays, a novella, a memoir, a research-based piece of creative nonfiction or a collection of poems. It is very, very difficult to write a novel in one semester, so unless you already have a novel underway, writing a novel is probably not a realistic thesis project. Creative works should be unified (by theme, by topic, or in some other way).

Students should already have taken a 200-level creative writing workshop in the chosen genre(s) and a 300- or 400-level workshop in this same genre(s). (You can be signed up to take the 400-level workshop in 494H semester.) Ideally, students will have studied creative writing with the faculty member who will serve as supervisor, but note that this is a suggestion and not a requirement. Schedule an initial meeting with your prospective thesis supervisor to discuss your plans for the execution of your creative work.

Note this requirement! Creative works will offer an introductory reflective essay (five to eight pages) outlining the project’s aims and placing the project into the context of the style and/or themes of work by other authors. The introductory reflection should address how your creative project complements or challenges work done by others. It should 1) explain the goals of the project and 2) place it into the context of relevant creative or critical texts. Any works referred to in this essay should be documented using Chicago, MLA, of APA style.

Note length stipulations: Honors theses in creative writing may be as short as 8,000 words but no longer than 15,000 words. If the thesis is shorter or longer than these advised limits, explain your thinking and decision-making in the introductory reflective essay.

The Thesis Supervisor

Schreyer Honors College requires thesis proposals to be submitted in early April of the year before graduation. For this reason, you must have a thesis supervisor by March, so that you can draft your proposal under the supervisor’s direction.