- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Observational Research

Definition:

Observational research is a type of research method where the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment. In other words, the researcher does not intervene or manipulate any variables but simply observes and describes what is happening.

Observation

Observation is the process of collecting and recording data by observing and noting events, behaviors, or phenomena in a systematic and objective manner. It is a fundamental method used in research, scientific inquiry, and everyday life to gain an understanding of the world around us.

Types of Observational Research

Observational research can be categorized into different types based on the level of control and the degree of involvement of the researcher in the study. Some of the common types of observational research are:

Naturalistic Observation

In naturalistic observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment without any interference or manipulation of variables.

Controlled Observation

In controlled observation, the researcher controls the environment in which the observation is taking place. This type of observation is often used in laboratory settings.

Participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher becomes an active participant in the group or situation being observed. The researcher may interact with the individuals being observed and gather data on their behavior, attitudes, and experiences.

Structured Observation

In structured observation, the researcher defines a set of behaviors or events to be observed and records their occurrence.

Unstructured Observation

In unstructured observation, the researcher observes and records any behaviors or events that occur without predetermined categories.

Cross-Sectional Observation

In cross-sectional observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of different individuals or groups at a single point in time.

Longitudinal Observation

In longitudinal observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of the same individuals or groups over an extended period of time.

Data Collection Methods

Observational research uses various data collection methods to gather information about the behaviors and experiences of individuals or groups being observed. Some common data collection methods used in observational research include:

Field Notes

This method involves recording detailed notes of the observed behavior, events, and interactions. These notes are usually written in real-time during the observation process.

Audio and Video Recordings

Audio and video recordings can be used to capture the observed behavior and interactions. These recordings can be later analyzed to extract relevant information.

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires can be used to gather additional information from the individuals or groups being observed. This method can be used to validate or supplement the observational data.

Time Sampling

This method involves taking a snapshot of the observed behavior at pre-determined time intervals. This method helps to identify the frequency and duration of the observed behavior.

Event Sampling

This method involves recording specific events or behaviors that are of interest to the researcher. This method helps to provide detailed information about specific behaviors or events.

Checklists and Rating Scales

Checklists and rating scales can be used to record the occurrence and frequency of specific behaviors or events. This method helps to simplify and standardize the data collection process.

Observational Data Analysis Methods

Observational Data Analysis Methods are:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves using statistical techniques such as frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations to summarize the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis involves identifying patterns and themes in the observed behaviors or interactions. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves categorizing and counting the occurrences of specific behaviors or events. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Time-series Analysis

Time-series analysis involves analyzing the changes in behavior or interactions over time. This analysis can help identify trends and patterns in the observed data.

Inter-observer Reliability Analysis

Inter-observer reliability analysis involves comparing the observations made by multiple observers to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis involves analyzing multiple variables simultaneously to identify the relationships between the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Event Coding

This method involves coding observed behaviors or events into specific categories and then analyzing the frequency and duration of each category.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis involves grouping similar behaviors or events into clusters based on their characteristics or patterns.

Latent Class Analysis

Latent class analysis involves identifying subgroups of individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors or interactions.

Social network Analysis

Social network analysis involves mapping the social relationships and interactions between individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors.

The choice of data analysis method depends on the research question, the type of data collected, and the available resources. Researchers should choose the appropriate method that best fits their research question and objectives. It is also important to ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis by using appropriate statistical tests and measures.

Applications of Observational Research

Observational research is a versatile research method that can be used in a variety of fields to explore and understand human behavior, attitudes, and preferences. Here are some common applications of observational research:

- Psychology : Observational research is commonly used in psychology to study human behavior in natural settings. This can include observing children at play to understand their social development or observing people’s reactions to stress to better understand how stress affects behavior.

- Marketing : Observational research is used in marketing to understand consumer behavior and preferences. This can include observing shoppers in stores to understand how they make purchase decisions or observing how people interact with advertisements to determine their effectiveness.

- Education : Observational research is used in education to study teaching and learning in natural settings. This can include observing classrooms to understand how teachers interact with students or observing students to understand how they learn.

- Anthropology : Observational research is commonly used in anthropology to understand cultural practices and beliefs. This can include observing people’s daily routines to understand their culture or observing rituals and ceremonies to better understand their significance.

- Healthcare : Observational research is used in healthcare to understand patient behavior and preferences. This can include observing patients in hospitals to understand how they interact with healthcare professionals or observing patients with chronic illnesses to better understand their daily routines and needs.

- Sociology : Observational research is used in sociology to understand social interactions and relationships. This can include observing people in public spaces to understand how they interact with others or observing groups to understand how they function.

- Ecology : Observational research is used in ecology to understand the behavior and interactions of animals and plants in their natural habitats. This can include observing animal behavior to understand their social structures or observing plant growth to understand their response to environmental factors.

- Criminology : Observational research is used in criminology to understand criminal behavior and the factors that contribute to it. This can include observing criminal activity in a particular area to identify patterns or observing the behavior of inmates to understand their experience in the criminal justice system.

Observational Research Examples

Here are some real-time observational research examples:

- A researcher observes and records the behaviors of a group of children on a playground to study their social interactions and play patterns.

- A researcher observes the buying behaviors of customers in a retail store to study the impact of store layout and product placement on purchase decisions.

- A researcher observes the behavior of drivers at a busy intersection to study the effectiveness of traffic signs and signals.

- A researcher observes the behavior of patients in a hospital to study the impact of staff communication and interaction on patient satisfaction and recovery.

- A researcher observes the behavior of employees in a workplace to study the impact of the work environment on productivity and job satisfaction.

- A researcher observes the behavior of shoppers in a mall to study the impact of music and lighting on consumer behavior.

- A researcher observes the behavior of animals in their natural habitat to study their social and feeding behaviors.

- A researcher observes the behavior of students in a classroom to study the effectiveness of teaching methods and student engagement.

- A researcher observes the behavior of pedestrians and cyclists on a city street to study the impact of infrastructure and traffic regulations on safety.

How to Conduct Observational Research

Here are some general steps for conducting Observational Research:

- Define the Research Question: Determine the research question and objectives to guide the observational research study. The research question should be specific, clear, and relevant to the area of study.

- Choose the appropriate observational method: Choose the appropriate observational method based on the research question, the type of data required, and the available resources.

- Plan the observation: Plan the observation by selecting the observation location, duration, and sampling technique. Identify the population or sample to be observed and the characteristics to be recorded.

- Train observers: Train the observers on the observational method, data collection tools, and techniques. Ensure that the observers understand the research question and objectives and can accurately record the observed behaviors or events.

- Conduct the observation : Conduct the observation by recording the observed behaviors or events using the data collection tools and techniques. Ensure that the observation is conducted in a consistent and unbiased manner.

- Analyze the data: Analyze the observed data using appropriate data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics, qualitative analysis, or content analysis. Validate the data by checking the inter-observer reliability and conducting statistical tests.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results by answering the research question and objectives. Identify the patterns, trends, or relationships in the observed data and draw conclusions based on the analysis.

- Report the findings: Report the findings in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate visual aids and tables. Discuss the implications of the results and the limitations of the study.

When to use Observational Research

Here are some situations where observational research can be useful:

- Exploratory Research: Observational research can be used in exploratory studies to gain insights into new phenomena or areas of interest.

- Hypothesis Generation: Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses about the relationships between variables, which can be tested using experimental research.

- Naturalistic Settings: Observational research is useful in naturalistic settings where it is difficult or unethical to manipulate the environment or variables.

- Human Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying human behavior, such as social interactions, decision-making, and communication patterns.

- Animal Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying animal behavior in their natural habitats, such as social and feeding behaviors.

- Longitudinal Studies: Observational research can be used in longitudinal studies to observe changes in behavior over time.

- Ethical Considerations: Observational research can be used in situations where manipulating the environment or variables would be unethical or impractical.

Purpose of Observational Research

Observational research is a method of collecting and analyzing data by observing individuals or phenomena in their natural settings, without manipulating them in any way. The purpose of observational research is to gain insights into human behavior, attitudes, and preferences, as well as to identify patterns, trends, and relationships that may exist between variables.

The primary purpose of observational research is to generate hypotheses that can be tested through more rigorous experimental methods. By observing behavior and identifying patterns, researchers can develop a better understanding of the factors that influence human behavior, and use this knowledge to design experiments that test specific hypotheses.

Observational research is also used to generate descriptive data about a population or phenomenon. For example, an observational study of shoppers in a grocery store might reveal that women are more likely than men to buy organic produce. This type of information can be useful for marketers or policy-makers who want to understand consumer preferences and behavior.

In addition, observational research can be used to monitor changes over time. By observing behavior at different points in time, researchers can identify trends and changes that may be indicative of broader social or cultural shifts.

Overall, the purpose of observational research is to provide insights into human behavior and to generate hypotheses that can be tested through further research.

Advantages of Observational Research

There are several advantages to using observational research in different fields, including:

- Naturalistic observation: Observational research allows researchers to observe behavior in a naturalistic setting, which means that people are observed in their natural environment without the constraints of a laboratory. This helps to ensure that the behavior observed is more representative of the real-world situation.

- Unobtrusive : Observational research is often unobtrusive, which means that the researcher does not interfere with the behavior being observed. This can reduce the likelihood of the research being affected by the observer’s presence or the Hawthorne effect, where people modify their behavior when they know they are being observed.

- Cost-effective : Observational research can be less expensive than other research methods, such as experiments or surveys. Researchers do not need to recruit participants or pay for expensive equipment, making it a more cost-effective research method.

- Flexibility: Observational research is a flexible research method that can be used in a variety of settings and for a range of research questions. Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses, to collect data on behavior, or to monitor changes over time.

- Rich data : Observational research provides rich data that can be analyzed to identify patterns and relationships between variables. It can also provide context for behaviors, helping to explain why people behave in a certain way.

- Validity : Observational research can provide high levels of validity, meaning that the results accurately reflect the behavior being studied. This is because the behavior is being observed in a natural setting without interference from the researcher.

Disadvantages of Observational Research

While observational research has many advantages, it also has some limitations and disadvantages. Here are some of the disadvantages of observational research:

- Observer bias: Observational research is prone to observer bias, which is when the observer’s own beliefs and assumptions affect the way they interpret and record behavior. This can lead to inaccurate or unreliable data.

- Limited generalizability: The behavior observed in a specific setting may not be representative of the behavior in other settings. This can limit the generalizability of the findings from observational research.

- Difficulty in establishing causality: Observational research is often correlational, which means that it identifies relationships between variables but does not establish causality. This can make it difficult to determine if a particular behavior is causing an outcome or if the relationship is due to other factors.

- Ethical concerns: Observational research can raise ethical concerns if the participants being observed are unaware that they are being observed or if the observations invade their privacy.

- Time-consuming: Observational research can be time-consuming, especially if the behavior being observed is infrequent or occurs over a long period of time. This can make it difficult to collect enough data to draw valid conclusions.

- Difficulty in measuring internal processes: Observational research may not be effective in measuring internal processes, such as thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. This can limit the ability to understand the reasons behind behavior.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Observation

Observation, as the name implies, is a way of collecting data through observing. This data collection method is classified as a participatory study, because the researcher has to immerse herself in the setting where her respondents are, while taking notes and/or recording. Observation data collection method may involve watching, listening, reading, touching, and recording behavior and characteristics of phenomena.

Observation as a data collection method can be structured or unstructured. In structured or systematic observation, data collection is conducted using specific variables and according to a pre-defined schedule. Unstructured observation, on the other hand, is conducted in an open and free manner in a sense that there would be no pre-determined variables or objectives.

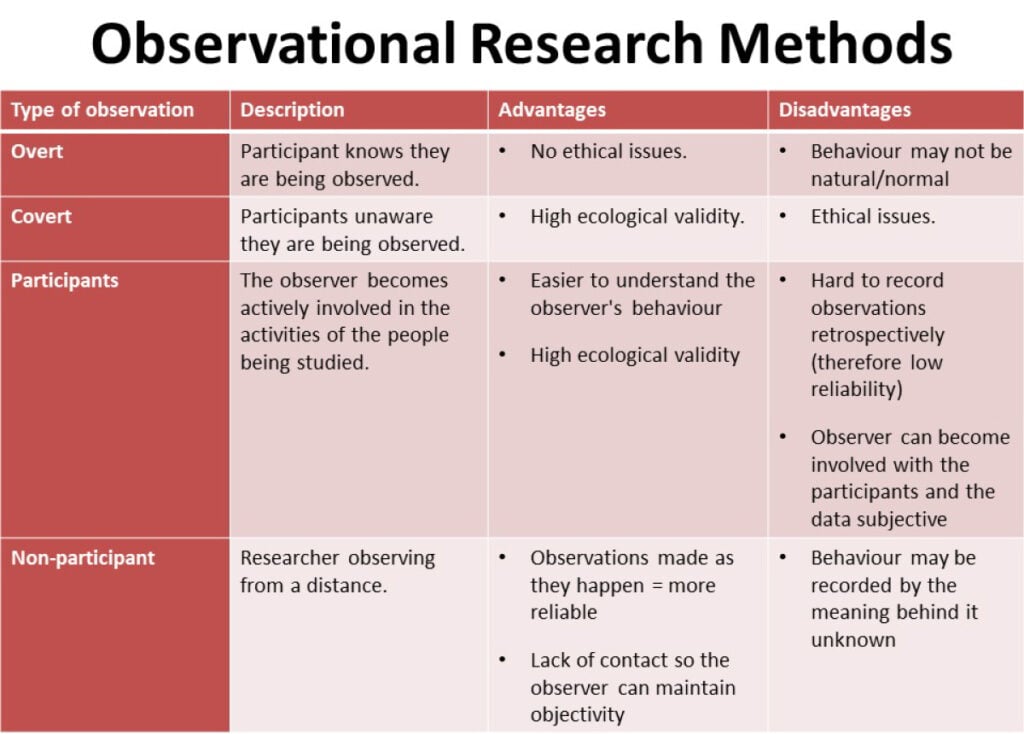

Moreover, this data collection method can be divided into overt or covert categories. In overt observation research subjects are aware that they are being observed. In covert observation, on the other hand, the observer is concealed and sample group members are not aware that they are being observed. Covert observation is considered to be more effective because in this case sample group members are likely to behave naturally with positive implications on the authenticity of research findings.

Advantages of observation data collection method include direct access to research phenomena, high levels of flexibility in terms of application and generating a permanent record of phenomena to be referred to later. At the same time, this method is disadvantaged with longer time requirements, high levels of observer bias, and impact of observer on primary data, in a way that presence of observer may influence the behaviour of sample group elements.

It is important to note that observation data collection method may be associated with certain ethical issues. As it is discussed further below in greater details, fully informed consent of research participant(s) is one of the basic ethical considerations to be adhered to by researchers. At the same time, the behaviour of sample group members may change with negative implications on the level of research validity if they are notified about the presence of the observer.

This delicate matter needs to be addressed by consulting with dissertation supervisor, and commencing the primary data collection process only after ethical aspects of the issue have been approved by the supervisor.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance offers practical assistance to complete a dissertation with minimum or no stress. The e-book covers all stages of writing a dissertation starting from the selection to the research area to submitting the completed version of the work within the deadline.

John Dudovskiy

Observation Method in Psychology: Naturalistic, Participant and Controlled

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The observation method in psychology involves directly and systematically witnessing and recording measurable behaviors, actions, and responses in natural or contrived settings without attempting to intervene or manipulate what is being observed.

Used to describe phenomena, generate hypotheses, or validate self-reports, psychological observation can be either controlled or naturalistic with varying degrees of structure imposed by the researcher.

There are different types of observational methods, and distinctions need to be made between:

1. Controlled Observations 2. Naturalistic Observations 3. Participant Observations

In addition to the above categories, observations can also be either overt/disclosed (the participants know they are being studied) or covert/undisclosed (the researcher keeps their real identity a secret from the research subjects, acting as a genuine member of the group).

In general, conducting observational research is relatively inexpensive, but it remains highly time-consuming and resource-intensive in data processing and analysis.

The considerable investments needed in terms of coder time commitments for training, maintaining reliability, preventing drift, and coding complex dynamic interactions place practical barriers on observers with limited resources.

Controlled Observation

Controlled observation is a research method for studying behavior in a carefully controlled and structured environment.

The researcher sets specific conditions, variables, and procedures to systematically observe and measure behavior, allowing for greater control and comparison of different conditions or groups.

The researcher decides where the observation will occur, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances, and uses a standardized procedure. Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

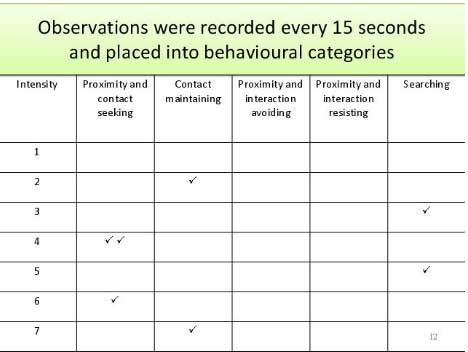

Rather than writing a detailed description of all behavior observed, it is often easier to code behavior according to a previously agreed scale using a behavior schedule (i.e., conducting a structured observation).

The researcher systematically classifies the behavior they observe into distinct categories. Coding might involve numbers or letters to describe a characteristic or the use of a scale to measure behavior intensity.

The categories on the schedule are coded so that the data collected can be easily counted and turned into statistics.

For example, Mary Ainsworth used a behavior schedule to study how infants responded to brief periods of separation from their mothers. During the Strange Situation procedure, the infant’s interaction behaviors directed toward the mother were measured, e.g.,

- Proximity and contact-seeking

- Contact maintaining

- Avoidance of proximity and contact

- Resistance to contact and comforting

The observer noted down the behavior displayed during 15-second intervals and scored the behavior for intensity on a scale of 1 to 7.

Sometimes participants’ behavior is observed through a two-way mirror, or they are secretly filmed. Albert Bandura used this method to study aggression in children (the Bobo doll studies ).

A lot of research has been carried out in sleep laboratories as well. Here, electrodes are attached to the scalp of participants. What is observed are the changes in electrical activity in the brain during sleep ( the machine is called an EEG ).

Controlled observations are usually overt as the researcher explains the research aim to the group so the participants know they are being observed.

Controlled observations are also usually non-participant as the researcher avoids direct contact with the group and keeps a distance (e.g., observing behind a two-way mirror).

- Controlled observations can be easily replicated by other researchers by using the same observation schedule. This means it is easy to test for reliability .

- The data obtained from structured observations is easier and quicker to analyze as it is quantitative (i.e., numerical) – making this a less time-consuming method compared to naturalistic observations.

- Controlled observations are fairly quick to conduct which means that many observations can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Controlled observations can lack validity due to the Hawthorne effect /demand characteristics. When participants know they are being watched, they may act differently.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is a research method in which the researcher studies behavior in its natural setting without intervention or manipulation.

It involves observing and recording behavior as it naturally occurs, providing insights into real-life behaviors and interactions in their natural context.

Naturalistic observation is a research method commonly used by psychologists and other social scientists.

This technique involves observing and studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in natural surroundings. The researcher simply records what they see in whatever way they can.

In unstructured observations, the researcher records all relevant behavior with a coding system. There may be too much to record, and the behaviors recorded may not necessarily be the most important, so the approach is usually used as a pilot study to see what type of behaviors would be recorded.

Compared with controlled observations, it is like the difference between studying wild animals in a zoo and studying them in their natural habitat.

With regard to human subjects, Margaret Mead used this method to research the way of life of different tribes living on islands in the South Pacific. Kathy Sylva used it to study children at play by observing their behavior in a playgroup in Oxfordshire.

Collecting Naturalistic Behavioral Data

Technological advances are enabling new, unobtrusive ways of collecting naturalistic behavioral data.

The Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR) is a digital recording device participants can wear to periodically sample ambient sounds, allowing representative sampling of daily experiences (Mehl et al., 2012).

Studies program EARs to record 30-50 second sound snippets multiple times per hour. Although coding the recordings requires extensive resources, EARs can capture spontaneous behaviors like arguments or laughter.

EARs minimize participant reactivity since sampling occurs outside of awareness. This reduces the Hawthorne effect, where people change behavior when observed.

The SenseCam is another wearable device that passively captures images documenting daily activities. Though primarily used in memory research currently (Smith et al., 2014), systematic sampling of environments and behaviors via the SenseCam could enable innovative psychological studies in the future.

- By being able to observe the flow of behavior in its own setting, studies have greater ecological validity.

- Like case studies , naturalistic observation is often used to generate new ideas. Because it gives the researcher the opportunity to study the total situation, it often suggests avenues of inquiry not thought of before.

- The ability to capture actual behaviors as they unfold in real-time, analyze sequential patterns of interactions, measure base rates of behaviors, and examine socially undesirable or complex behaviors that people may not self-report accurately.

- These observations are often conducted on a micro (small) scale and may lack a representative sample (biased in relation to age, gender, social class, or ethnicity). This may result in the findings lacking the ability to generalize to wider society.

- Natural observations are less reliable as other variables cannot be controlled. This makes it difficult for another researcher to repeat the study in exactly the same way.

- Highly time-consuming and resource-intensive during the data coding phase (e.g., training coders, maintaining inter-rater reliability, preventing judgment drift).

- With observations, we do not have manipulations of variables (or control over extraneous variables), meaning cause-and-effect relationships cannot be established.

Participant Observation

Participant observation is a variant of the above (natural observations) but here, the researcher joins in and becomes part of the group they are studying to get a deeper insight into their lives.

If it were research on animals , we would now not only be studying them in their natural habitat but be living alongside them as well!

Leon Festinger used this approach in a famous study into a religious cult that believed that the end of the world was about to occur. He joined the cult and studied how they reacted when the prophecy did not come true.

Participant observations can be either covert or overt. Covert is where the study is carried out “undercover.” The researcher’s real identity and purpose are kept concealed from the group being studied.

The researcher takes a false identity and role, usually posing as a genuine member of the group.

On the other hand, overt is where the researcher reveals his or her true identity and purpose to the group and asks permission to observe.

- It can be difficult to get time/privacy for recording. For example, researchers can’t take notes openly with covert observations as this would blow their cover. This means they must wait until they are alone and rely on their memory. This is a problem as they may forget details and are unlikely to remember direct quotations.

- If the researcher becomes too involved, they may lose objectivity and become biased. There is always the danger that we will “see” what we expect (or want) to see. This problem is because they could selectively report information instead of noting everything they observe. Thus reducing the validity of their data.

Recording of Data

With controlled/structured observation studies, an important decision the researcher has to make is how to classify and record the data. Usually, this will involve a method of sampling.

In most coding systems, codes or ratings are made either per behavioral event or per specified time interval (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

The three main sampling methods are:

Event-based coding involves identifying and segmenting interactions into meaningful events rather than timed units.

For example, parent-child interactions may be segmented into control or teaching events to code. Interval recording involves dividing interactions into fixed time intervals (e.g., 6-15 seconds) and coding behaviors within each interval (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

Event recording allows counting event frequency and sequencing while also potentially capturing event duration through timed-event recording. This provides information on time spent on behaviors.

Coding Systems

The coding system should focus on behaviors, patterns, individual characteristics, or relationship qualities that are relevant to the theory guiding the study (Wampler & Harper, 2014).

Codes vary in how much inference is required, from concrete observable behaviors like frequency of eye contact to more abstract concepts like degree of rapport between a therapist and client (Hill & Lambert, 2004). More inference may reduce reliability.

Macroanalytic coding systems

Macroanalytic coding systems involve rating or summarizing behaviors using larger coding units and broader categories that reflect patterns across longer periods of interaction rather than coding small or discrete behavioral acts.

For example, a macroanalytic coding system may rate the overall degree of therapist warmth or level of client engagement globally for an entire therapy session, requiring the coders to summarize and infer these constructs across the interaction rather than coding smaller behavioral units.

These systems require observers to make more inferences (more time-consuming) but can better capture contextual factors, stability over time, and the interdependent nature of behaviors (Carlson & Grotevant, 1987).

Microanalytic coding systems

Microanalytic coding systems involve rating behaviors using smaller, more discrete coding units and categories.

For example, a microanalytic system may code each instance of eye contact or head nodding during a therapy session. These systems code specific, molecular behaviors as they occur moment-to-moment rather than summarizing actions over longer periods.

Microanalytic systems require less inference from coders and allow for analysis of behavioral contingencies and sequential interactions between therapist and client. However, they are more time-consuming and expensive to implement than macroanalytic approaches.

Mesoanalytic coding systems

Mesoanalytic coding systems attempt to balance macro- and micro-analytic approaches.

In contrast to macroanalytic systems that summarize behaviors in larger chunks, mesoanalytic systems use medium-sized coding units that target more specific behaviors or interaction sequences (Bakeman & Quera, 2017).

For example, a mesoanalytic system may code each instance of a particular type of therapist statement or client emotional expression. However, mesoanalytic systems still use larger units than microanalytic approaches coding every speech onset/offset.

The goal of balancing specificity and feasibility makes mesoanalytic systems well-suited for many research questions (Morris et al., 2014). Mesoanalytic codes can preserve some sequential information while remaining efficient enough for studies with adequate but limited resources.

For instance, a mesoanalytic couple interaction coding system could target key behavior patterns like validation sequences without coding turn-by-turn speech.

In this way, mesoanalytic coding allows reasonable reliability and specificity without requiring extensive training or observation. The mid-level focus offers a pragmatic compromise between depth and breadth in analyzing interactions.

Preventing Coder Drift

Coder drift results in a measurement error caused by gradual shifts in how observations get rated according to operational definitions, especially when behavioral codes are not clearly specified.

This type of error creeps in when coders fail to regularly review what precise observations constitute or do not constitute the behaviors being measured.

Preventing drift refers to taking active steps to maintain consistency and minimize changes or deviations in how coders rate or evaluate behaviors over time. Specifically, some key ways to prevent coder drift include:

- Operationalize codes : It is essential that code definitions unambiguously distinguish what interactions represent instances of each coded behavior.

- Ongoing training : Returning to those operational definitions through ongoing training serves to recalibrate coder interpretations and reinforce accurate recognition. Having regular “check-in” sessions where coders practice coding the same interactions allows monitoring that they continue applying codes reliably without gradual shifts in interpretation.

- Using reference videos : Coders periodically coding the same “gold standard” reference videos anchors their judgments and calibrate against original training. Without periodic anchoring to original specifications, coder decisions tend to drift from initial measurement reliability.

- Assessing inter-rater reliability : Statistical tracking that coders maintain high levels of agreement over the course of a study, not just at the start, flags any declines indicating drift. Sustaining inter-rater agreement requires mitigating this common tendency for observer judgment change during intensive, long-term coding tasks.

- Recalibrating through discussion : Having meetings for coders to discuss disagreements openly explores reasons judgment shifts may be occurring over time. Consensus on the application of codes is restored.

- Adjusting unclear codes : If reliability issues persist, revisiting and refining ambiguous code definitions or anchors can eliminate inconsistencies arising from coder confusion.

Essentially, the goal of preventing coder drift is maintaining standardization and minimizing unintentional biases that may slowly alter how observational data gets rated over periods of extensive coding.

Through the upkeep of skills, continuing calibration to benchmarks, and monitoring consistency, researchers can notice and correct for any creeping changes in coder decision-making over time.

Reducing Observer Bias

Observational research is prone to observer biases resulting from coders’ subjective perspectives shaping the interpretation of complex interactions (Burghardt et al., 2012). When coding, personal expectations may unconsciously influence judgments. However, rigorous methods exist to reduce such bias.

Coding Manual

A detailed coding manual minimizes subjectivity by clearly defining what behaviors and interaction dynamics observers should code (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

High-quality manuals have strong theoretical and empirical grounding, laying out explicit coding procedures and providing rich behavioral examples to anchor code definitions (Lindahl, 2001).

Clear delineation of the frequency, intensity, duration, and type of behaviors constituting each code facilitates reliable judgments and reduces ambiguity for coders. Application risks inconsistency across raters without clarity on how codes translate to observable interaction.

Coder Training

Competent coders require both interpersonal perceptiveness and scientific rigor (Wampler & Harper, 2014). Training thoroughly reviews the theoretical basis for coded constructs and teaches the coding system itself.

Multiple “gold standard” criterion videos demonstrate code ranges that trainees independently apply. Coders then meet weekly to establish reliability of 80% or higher agreement both among themselves and with master criterion coding (Hill & Lambert, 2004).

Ongoing training manages coder drift over time. Revisions to unclear codes may also improve reliability. Both careful selection and investment in rigorous training increase quality control.

Blind Methods

To prevent bias, coders should remain unaware of specific study predictions or participant details (Burghardt et al., 2012). Separate data gathering versus coding teams helps maintain blinding.

Coders should be unaware of study details or participant identities that could bias coding (Burghardt et al., 2012).

Separate teams collecting data versus coding data can reduce bias.

In addition, scheduling procedures can prevent coders from rating data collected directly from participants with whom they have had personal contact. Maintaining coder independence and blinding enhances objectivity.

Bakeman, R., & Quera, V. (2017). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Burghardt, G. M., Bartmess-LeVasseur, J. N., Browning, S. A., Morrison, K. E., Stec, C. L., Zachau, C. E., & Freeberg, T. M. (2012). Minimizing observer bias in behavioral studies: A review and recommendations. Ethology, 118 (6), 511-517.

Hill, C. E., & Lambert, M. J. (2004). Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 84–135). Wiley.

Lindahl, K. M. (2001). Methodological issues in family observational research. In P. K. Kerig & K. M. Lindahl (Eds.), Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research (pp. 23–32). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mehl, M. R., Robbins, M. L., & Deters, F. G. (2012). Naturalistic observation of health-relevant social processes: The electronically activated recorder methodology in psychosomatics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74 (4), 410–417.

Morris, A. S., Robinson, L. R., & Eisenberg, N. (2014). Applying a multimethod perspective to the study of developmental psychology. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (2nd ed., pp. 103–123). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, J. A., Maxwell, S. D., & Johnson, G. (2014). The microstructure of everyday life: Analyzing the complex choreography of daily routines through the automatic capture and processing of wearable sensor data. In B. K. Wiederhold & G. Riva (Eds.), Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2014: Positive Change with Technology (Vol. 199, pp. 62-64). IOS Press.

Traniello, J. F., & Bakker, T. C. (2015). The integrative study of behavioral interactions across the sciences. In T. K. Shackelford & R. D. Hansen (Eds.), The evolution of sexuality (pp. 119-147). Springer.

Wampler, K. S., & Harper, A. (2014). Observational methods in couple and family assessment. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (2nd ed., pp. 490–502). Cambridge University Press.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

32 Observational Research

Learning objectives.

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation . Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation , the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation , the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

In yet another example (this one in a laboratory environment), Dov Cohen and his colleagues had observers rate the emotional reactions of participants who had just been deliberately bumped and insulted by a confederate after they dropped off a completed questionnaire at the end of a hallway. The confederate was posing as someone who worked in the same building and who was frustrated by having to close a file drawer twice in order to permit the participants to walk past them (first to drop off the questionnaire at the end of the hallway and once again on their way back to the room where they believed the study they signed up for was taking place). The two observers were positioned at different ends of the hallway so that they could read the participants’ body language and hear anything they might say. Interestingly, the researchers hypothesized that participants from the southern United States, which is one of several places in the world that has a “culture of honor,” would react with more aggression than participants from the northern United States, a prediction that was in fact supported by the observational data (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) [6] .

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in the studies by Kraut and Johnston and Cohen and his colleagues—a process referred to as coding is typically required . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that guides different observers to code them in the same way. This difficulty with coding illustrates the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Chapter 4. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

One of the primary benefits of structured observation is that it is far more efficient than naturalistic and participant observation. Since the researchers are focused on specific behaviors this reduces time and expense. Also, often times the environment is structured to encourage the behaviors of interest which again means that researchers do not have to invest as much time in waiting for the behaviors of interest to naturally occur. Finally, researchers using this approach can clearly exert greater control over the environment. However, when researchers exert more control over the environment it may make the environment less natural which decreases external validity. It is less clear for instance whether structured observations made in a laboratory environment will generalize to a real world environment. Furthermore, since researchers engaged in structured observation are often not disguised there may be more concerns with reactivity.

Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of an individual. Sometimes case studies are also completed on social units (e.g., a cult) and events (e.g., a natural disaster). Most commonly in psychology, however, case studies provide a detailed description and analysis of an individual. Often the individual has a rare or unusual condition or disorder or has damage to a specific region of the brain.

Like many observational research methods, case studies tend to be more qualitative in nature. Case study methods involve an in-depth, and often a longitudinal examination of an individual. Depending on the focus of the case study, individuals may or may not be observed in their natural setting. If the natural setting is not what is of interest, then the individual may be brought into a therapist’s office or a researcher’s lab for study. Also, the bulk of the case study report will focus on in-depth descriptions of the person rather than on statistical analyses. With that said some quantitative data may also be included in the write-up of a case study. For instance, an individual’s depression score may be compared to normative scores or their score before and after treatment may be compared. As with other qualitative methods, a variety of different methods and tools can be used to collect information on the case. For instance, interviews, naturalistic observation, structured observation, psychological testing (e.g., IQ test), and/or physiological measurements (e.g., brain scans) may be used to collect information on the individual.

HM is one of the most notorious case studies in psychology. HM suffered from intractable and very severe epilepsy. A surgeon localized HM’s epilepsy to his medial temporal lobe and in 1953 he removed large sections of his hippocampus in an attempt to stop the seizures. The treatment was a success, in that it resolved his epilepsy and his IQ and personality were unaffected. However, the doctors soon realized that HM exhibited a strange form of amnesia, called anterograde amnesia. HM was able to carry out a conversation and he could remember short strings of letters, digits, and words. Basically, his short term memory was preserved. However, HM could not commit new events to memory. He lost the ability to transfer information from his short-term memory to his long term memory, something memory researchers call consolidation. So while he could carry on a conversation with someone, he would completely forget the conversation after it ended. This was an extremely important case study for memory researchers because it suggested that there’s a dissociation between short-term memory and long-term memory, it suggested that these were two different abilities sub-served by different areas of the brain. It also suggested that the temporal lobes are particularly important for consolidating new information (i.e., for transferring information from short-term memory to long-term memory).

The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 6.1 “The Case of “Anna O.””) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920) [7] , who allegedly learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers repeatedly made a loud noise every time the rat approached him.

The Case of “Anna O.”

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961) [8] . (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. (p. 9)

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. (p.9)

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, he believed that her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Case studies are useful because they provide a level of detailed analysis not found in many other research methods and greater insights may be gained from this more detailed analysis. As a result of the case study, the researcher may gain a sharpened understanding of what might become important to look at more extensively in future more controlled research. Case studies are also often the only way to study rare conditions because it may be impossible to find a large enough sample of individuals with the condition to use quantitative methods. Although at first glance a case study of a rare individual might seem to tell us little about ourselves, they often do provide insights into normal behavior. The case of HM provided important insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation.

However, it is important to note that while case studies can provide insights into certain areas and variables to study, and can be useful in helping develop theories, they should never be used as evidence for theories. In other words, case studies can be used as inspiration to formulate theories and hypotheses, but those hypotheses and theories then need to be formally tested using more rigorous quantitative methods. The reason case studies shouldn’t be used to provide support for theories is that they suffer from problems with both internal and external validity. Case studies lack the proper controls that true experiments contain. As such, they suffer from problems with internal validity, so they cannot be used to determine causation. For instance, during HM’s surgery, the surgeon may have accidentally lesioned another area of HM’s brain (a possibility suggested by the dissection of HM’s brain following his death) and that lesion may have contributed to his inability to consolidate new information. The fact is, with case studies we cannot rule out these sorts of alternative explanations. So, as with all observational methods, case studies do not permit determination of causation. In addition, because case studies are often of a single individual, and typically an abnormal individual, researchers cannot generalize their conclusions to other individuals. Recall that with most research designs there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. With case studies, however, there are problems with both internal validity and external validity. So there are limits both to the ability to determine causation and to generalize the results. A final limitation of case studies is that ample opportunity exists for the theoretical biases of the researcher to color or bias the case description. Indeed, there have been accusations that the woman who studied HM destroyed a lot of her data that were not published and she has been called into question for destroying contradictory data that didn’t support her theory about how memories are consolidated. There is a fascinating New York Times article that describes some of the controversies that ensued after HM’s death and analysis of his brain that can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/magazine/the-brain-that-couldnt-remember.html?_r=0

Archival Research

Another approach that is often considered observational research involves analyzing archival data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005) [9] . In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988) [10] . In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This method is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as structured observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

Media Attributions

- What happens when you remove the hippocampus? – Sam Kean by TED-Ed licensed under a standard YouTube License

- Pappenheim 1882 by unknown is in the Public Domain .

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205. ↵

- Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553. ↵

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An "experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 945-960. ↵

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14. ↵

- Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton. ↵

- Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110. ↵

- Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27. ↵

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

An observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs.

When researchers engage in naturalistic observation by making their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied.

Where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior.

Refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior.

In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, it is a type of reactivity when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would.

Researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying.

Researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

Researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation.

When a researcher makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation.

A part of structured observation whereby the observers use a clearly defined set of guidelines to "code" behaviors—assigning specific behaviors they are observing to a category—and count the number of times or the duration that the behavior occurs.

An in-depth examination of an individual.

A family of systematic approaches to measurement using qualitative methods to analyze complex archival data.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics