Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

The Meticulously Crafted Adventures of David Grann

How a bookish reporter became one of the most sought-after writers in hollywood..

David Grann is the first to say he isn’t a natural-born explorer. Thanks to a degenerative eye condition, the longtime New Yorker writer sees the world as though looking through a windshield during a rainstorm. He doesn’t hike or camp, and he has a tendency to take the wrong train when he rides the subway. While researching The Lost City of Z , his 2009 book about a Victorian-era adventurer who went missing in the Amazon and never returned, he briefly got lost in the Amazon himself. So it wasn’t all that surprising when, on a sunny morning in April, Grann showed up at the wrong location for our interview. When I found him on the sidewalk near the South Street Seaport Museum, where we were supposed to meet, he was grinning from ear to ear. “It’s just like me to get lost,” he said, laughing.

Grann, 56, may not have the strapping physical attributes of his subjects, but his meticulously researched stories, with their spare, simmering setups that almost always deliver stunning payoffs, have made him one of the preeminent adventure and true-crime writers working today. “We often think that reporters have to be super-capable in every way in order to get the best material, but sometimes if you have something like weak sight, you compensate in such a brilliant way that it’s better than if you have the best vision,” said Daniel Zalewski, Grann’s longtime editor at The New Yorker . In just over a decade, Grann has published The Lost City of Z ; Killers of the Flower Moon , about the targeted assassinations of members of the Osage Nation; The White Darkness , about a polar explorer obsessed with crossing Antarctica alone; and two collections’ worth of magazine stories about murderers, master manipulators, and scientists on the hunt for the elusive giant squid.

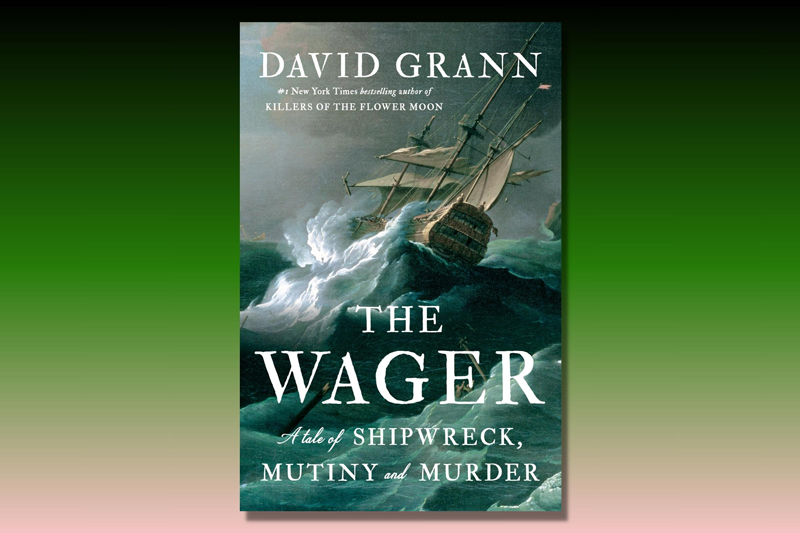

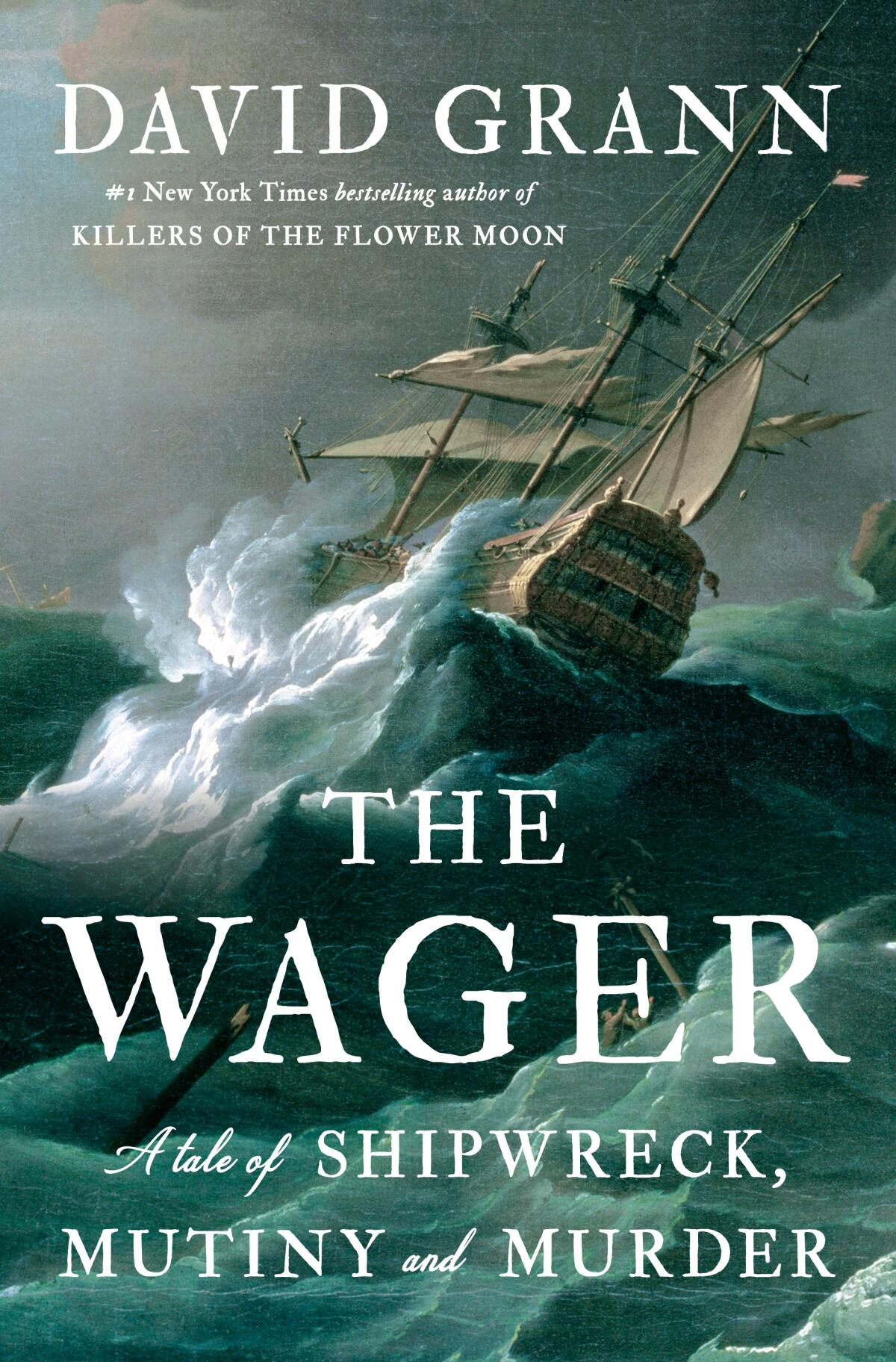

His latest book, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder , traces the journey of the H.M.S. Wager , a British warship that ran aground on a Pacific island in 1742 while on a secret mission. Stranded, the crew members mutinied and spent months fighting for survival, testing not only their physical limits but those of military law and the social order. Multiple groups of survivors miraculously made it back to England only to offer different, sometimes conflicting, accounts of the ordeal. More than the adventure story, the Rashomon -like atmosphere is what gives The Wager the intellectual heft of a David Grann endeavor. “After all they had been through — scurvy, shipwrecks, typhoons, violence — these castaway voyagers are summoned to face court-martial, and they could be hanged. So hoping to save their lives, they released testimony or written accounts, which became quite a sensation, but they also sparked this furious war over the truth,” Grann said.

After spending two years poring over journals, court records, and logbooks, he still felt he could never fully understand the experience of the Wager ’s crew unless he visited the island. That’s how this reluctant explorer found himself sitting in a small boat as it motored across a stretch of Pacific Ocean often referred to as the Gulf of Pain, while waves tossed the 50-foot vessel around like a soda can. “That journey was probably stupid, probably foolish, but in the end was really essential,” Grann said. As he walked around the island, the brutal conditions the sailors described — the windchill, the lack of food, the dense foliage that suffocated their movement — felt real. “I understood why this British officer had called Wager Island the kind of place where the soul of man dies. I’m like, Okay, my soul would have died here .”

Grann grew up in Westport, Connecticut, the middle child of the late Victor Grann, a cancer specialist and recreational sailor who occasionally exhibited some of the madman qualities his son would later explore in his subjects (“If a hurricane was coming he would not sail away from it,” Grann said), and Phyllis Grann , a powerhouse book editor and publisher who shared one piece of wisdom above all: Don’t become a writer.

Like any good child, he ignored his mother’s advice. After graduating from Connecticut College, he wrote a coming-of-age novel that he never published and briefly taught fiction while getting a master’s degree in creative writing at Boston University. Eventually, he gave up on fiction and committed himself to journalism, where he has mastered a streamlined, propulsive type of narrative that readers devour for its hide-and-seek reveals. The success of that form is indisputable — Killers of the Flower Moon has sold over a million copies — but it’s not without detractors. “If you taught the artificial brains of supercomputers at IBM Research to write nonfiction prose, and if they got very good at it, they might compose a book like David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon ,” Dwight Garner wrote in his New York Times review. Grann, however, is diligent about removing stylistic flourishes from his writing. “You’re really only as good as the material you’re working with,” he said. “You might be able to improve it some, or you may not make it as good as it could have been, but at some level, if the material isn’t good, you’re kind of sunk.”

“David spends weeks and weeks and months and months sifting through possible stories,” said David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker . “I’d wander by his office and he’d be reading these archives and old letters and all kind of material, holding the paper close to his face like an ancient Talmudic scholar.”

Nowhere are the twists and turns of Grann’s stories more hotly anticipated than in Hollywood. According to one film scout, producers sometimes hear about Grann’s ideas before he has committed to pursuing them. Four of his stories have been adapted into movies, and at least four others are in development as either films or series. The bidding war for Killers of the Flower Moon was heated, with the winners paying a reported $5 million for the rights. Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio ultimately signed on to make the film, which is scheduled to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May. Scorsese and DiCaprio acquired the rights for The Wager last July, nearly a year before its publication.

Inside the Seaport Museum — where Grann revels in the knowledge that its tall ship, the Wavertree , was once battered rounding Cape Horn, just like the Wager — he tells me he doesn’t think about his projects as movies. His interest in the Wager was stoked by an 18th-century account written in stilted English, hardly cinematic gold. This account was given by John Byron (who would one day be the grandfather of the poet Lord Byron), who was 16 when he left Portsmouth aboard the Wager . As Byron’s story was one of a handful given by survivors, “I tried to gather all the facts to determine what really happened,” Grann writes in an author’s note at the beginning of the book.

Where other writers might take liberties, Grann is obsessive about accuracy. “David’s stuff reads like literature, but every detail, every quote, every seemingly implausible glimpse into a subject’s mind is accounted for,” said David Kortava, who fact-checked both The White Darkness and The Wager . Grann verifies his own work before sending it to a fact-checker, and his devotion to the fact-checking process can seem comical. The first time he asked Kortava if he had checked the spellings of his kids’ names on The Wager ’s dedication page, Kortava thought Grann was joking. The second time he asked, Kortava checked the spellings. “He doesn’t have an OCD diagnosis, as far as I know, but I do, and I definitely consider him one of the tribe,” Kortava said.

Grann didn’t always have the freedom to pursue his idiosyncratic interests. He was once a general-assignment magazine writer delivering stories about Barry Bonds, John McCain, and Newt Gingrich. A 2000 profile of the now-deceased Ohio congressman Jim Traficant that Grann wrote for The New Republic helped him discover the types of stories he wanted to tell and how to go about telling them. In an Ohio courthouse, Grann unearthed a 1980 recording of Traficant, then a candidate for sheriff, talking to two mobsters. “I hear Traficant dropping the F-bomb every other word, and I hear him talking about taking bribes, and then I hear about people coming up swimming in the Mahoning River. And it was a voice that was so different from the voice I heard on C-SPAN,” Grann said. “It was kind of the beginning where I was thinking, Oh! These are the voices of the stories I want to tell . It also showed me the power of archives for the first time. You can find things that are just kind of sitting there if you look, and they can peel back façades and get you closer to the hidden truth.”

I ask Grann if he misses reporting on contemporary figures. He holds up his hand and makes a zero with his fingers while letting out a sigh of relief. “The kind of reporting I really like to do is so immersive, and usually figures like that do not want you to be with them,” he said. Their ghosts, he has learned, have no choice.

- david grann

- the new yorker

Most Viewed Stories

- Paul Krugman Is Right About the Economy, and the Polls Are Wrong

- ‘Sleepy Don’: Trump Falls Asleep (Again!) During Hush-Money Trial

- Trump’s Gettysburg Address Featured a Pirate Impression

- Elon Musk Has Forgotten What Tesla Is

- The Never Trumper Listening to Trump Voters

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

- Paul Krugman Is Right About the Economy, and the Polls Are Wrong By Jonathan Chait

- ‘Sleepy Don’: Trump Falls Asleep (Again!) During Hush-Money Trial By Margaret Hartmann

- Trump’s Gettysburg Address Featured a Pirate Impression By Margaret Hartmann

- Elon Musk Has Forgotten What Tesla Is By Kevin T. Dugan

- The Never Trumper Listening to Trump Voters By David Freedlander

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

by David Grann

D avid Grann, the best-selling author of Killers of the Flower Moon and The Lost City of Z , returns with another historical epic about a mystery nearly lost to time. The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder recounts the thrilling true story of the HMS Wager, a sixth-rate Royal Navy ship, and a mutiny that may or may not have taken place. It’s not an easy story to tell, as Grann freely admits in his opening author’s note, being that “the participants’ conflicting, and at times warring, perspectives” were all he had to go by. What we know for sure: in January 1742, a deteriorated boat washed up on the shores of Brazil with 30 men who claimed they were the survivors of the shipwrecked Wager—and yet six months later another vessel landed in Chile with three men who swore that those castaways were actually mutineers.

Using the crew’s log books, daily journals, and court testimony, Grann paints a gruesome portrait of the danger and uncertainty that came with being a sailor in the 18th century. In 1740, 250 men set sail from England on a secret mission. The threat of war was all around, but so was the fear of dying at sea of scurvy, typhus, or delirium. (Grann describes, in gory detail, a table used aboard the warship to amputate rotting limbs without anesthesia.) Once the crew is marooned on an island off the coast of Chilean Patagonia, he writes in stunning detail about the ghastly lengths they went to to survive, with some turning to cannibalism to fend off starvation. He describes how the men were saved by the island’s indigenous people—Kawésqar and the Chono—but, because of their imperialist upbringing, couldn’t help but refer to their saviors as “savages.” In Grann’s capable hands, The Wager is not just a suspenseful mystery at sea, it’s also a page-turning tragic farce in which there may be no heroes and villains, just mortal men suffering from delusions of grandeur. — Shannon Carlin

Buy Now: The Wager on Bookshop | Amazon

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected] .

All the Sinners Bleed

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Reviews of The Wager by David Grann

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder

by David Grann

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- History, Current Affairs and Religion

- Central & S. America, Mexico, Caribbean

- On The High Seas

- UK (Britain) & Ireland

- 17th Century or Earlier

- Top 20 Best Books of 2023

Rate this book

About this Book

Book summary.

Winner: BookBrowse Nonfiction Award 2023 From the #1 New York Times bestselling author of Killers of the Flower Moon , a page-turning story of shipwreck, survival, and savagery, culminating in a court martial that reveals a shocking truth. The powerful narrative reveals the deeper meaning of the events on The Wager , showing that it was not only the captain and crew who ended up on trial, but the very idea of empire.

On January 28, 1742, a ramshackle vessel of patched-together wood and cloth washed up on the coast of Brazil. Inside were thirty emaciated men, barely alive, and they had an extraordinary tale to tell. They were survivors of His Majesty's Ship the Wager, a British vessel that had left England in 1740 on a secret mission during an imperial war with Spain. While the Wager had been chasing a Spanish treasure-filled galleon known as "the prize of all the oceans," it had wrecked on a desolate island off the coast of Patagonia. The men, after being marooned for months and facing starvation, built the flimsy craft and sailed for more than a hundred days, traversing nearly 3,000 miles of storm-wracked seas. They were greeted as heroes. But then ... six months later, another, even more decrepit craft landed on the coast of Chile. This boat contained just three castaways, and they told a very different story. The thirty sailors who landed in Brazil were not heroes – they were mutineers. The first group responded with countercharges of their own, of a tyrannical and murderous senior officer and his henchmen. It became clear that while stranded on the island the crew had fallen into anarchy, with warring factions fighting for dominion over the barren wilderness. As accusations of treachery and murder flew, the Admiralty convened a court martial to determine who was telling the truth. The stakes were life-and-death—for whomever the court found guilty could hang. The Wager is a grand tale of human behavior at the extremes told by one of our greatest nonfiction writers. Grann's recreation of the hidden world on a British warship rivals the work of Patrick O'Brian, his portrayal of the castaways' desperate straits stands up to the classics of survival writing such as The Endurance , and his account of the court martial has the savvy of a Scott Turow thriller. As always with Grann's work, the incredible twists of the narrative hold the reader spellbound.

The First Lieutenant Each man in the squadron carried, along with a sea chest, his own burdensome story. Perhaps it was of a scorned love, or a secret prison conviction, or a pregnant wife left on shore weeping. Perhaps it was a hunger for fame and fortune, or a dread of death. David Cheap, the first lieutenant of the Centurion, the squadron's flagship, was no different. A burly Scotsman in his early forties with a protracted nose and intense eyes, he was in flight—from squabbles with his brother over their inheritance, from creditors chasing him, from debts that made it impossible for him to find a suitable bride. Onshore, Cheap seemed doomed, unable to navigate past life's unexpected shoals. Yet as he perched on the quarterdeck of a British man-of-war, cruising the vast oceans with a cocked hat and spyglass, he brimmed with confidence—even, some would say, a touch of haughtiness. The wooden world of a ship—a world bound by the Navy's rigid regulations and ...

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

BookBrowse Awards 2023

Media Reviews

Reader reviews, bookbrowse review.

Winner: BookBrowse Nonfiction Award 2023 I found this book to be well-researched, well-written and extremely easy to read. It was actually quite a thrilling read to be honest. It felt more like I was reading an adventure book than a nonfiction book (Tara T). Although the subject matter was not of great interest to me when I started reading the book, my opinion quickly changed when more of the narrative was developed. The author takes a maritime scandal and engulfs the reader in a suspenseful historical thriller! (Dan W). It's a riveting, page-turning adventure, complete with shipwreck, mutiny and murder (Lois K)... continued

(Reviewed by BookBrowse First Impression Reviewers ).

Write your own review!

Beyond the Book

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked The Wager, try these:

The Wide Wide Sea

by Hampton Sides

Published 2024

About this book

More by this author

From New York Times bestselling author Hampton Sides, an epic account of the most momentous voyage of the Age of Exploration, which culminated in Captain James Cook's death in Hawaii, and left a complex and controversial legacy still debated to this day

by Scott Carney , Jason Miklian

Published 2023

The deadliest storm in modern history ripped Pakistan in two and led the world to the brink of nuclear war when American and Soviet forces converged in the Bay of Bengal.

Books with similar themes

Support bookbrowse.

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The House on Biscayne Bay by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim

A moving family drama and coming-of-age story revealing a dark corner of South Korean history.

Win This Book

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

Why a Harrowing 18th-Century Shipwreck Is a Parable for Our Times

By Sean Woods

Editor’s picks

The 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, the 50 worst decisions in movie history, every awful thing trump has promised to do in a second term.

It’s incredible that anyone survived given the calamities and deprivations the crew faced. Yeah, but I was looking for a deeper resonance. Why resuscitate and revive and spend years excavating something from the 18th century? But as I started to dive into archives and pull journals, I realized that as interesting as what had happened on the island was, what happened after several of the survivors made it back to England was even more incredible. They’d waged this war against every element and now, suddenly, they are summoned to face a court martial. And if they don’t tell a convincing tale, they could be hanged. And so, in hoping to save their lives, they release these various accounts trying to depict themselves as the heroes of the story. They all begin to wage a war on the truth.

That’s all too close to home. Yes, because there’s a war over history right now. Like, what history books can we teach? There was a teacher who was afraid to teach Killers of the Flower Moon in her school in Oklahoma, and the books were just piling up.

'Doomsday Dad' Chad Daybell's Lawyer Blames Lori Vallow for Family Murders

Martin scorsese to spearhead doc series on christian saints for fox nation, dancehall artist vybz kartel's murder conviction overturned.

It’s really a Rashomon-like story. When you’re dealing with competing narratives, as a journalist and a historian, how do you weigh the differing accounts? At some level you can never completely resolve it. Joan Didion famously said, “We all tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Yet, in this case of the men of the Wager, they quite literally have to tell their stories in order to live. And if they don’t tell a good one, they’re going to get hanged. I had never seen such a case where you can see each individual shaping their story and burnishing certain facts and leaving out other facts. And so, I decided rather than try to be some omniscient being, the best way to handle it was just simply to show it.

There are still multiple conflicting accounts of the events. I chose to tell the story from the perspective of three of the men, all of whom served on the Wager: Captain David Cheap; John Bulkeley, the gunner; and then John Byron, the midshipman. And thereby show how each one is shaping the facts. I leave it up to the reader to judge as best as they can. My feeling was that by doing that, you gain insight into how we all shape our stories, and how we all hope to emerge as the heroes of them — in order to live with what we’ve done or haven’t done.

What’s left out of history is in many ways some of the most tragic parts of the book. Absolutely. One of the Wager’s castaways was named John Duck, who was a free black sailor at the time. And he is somebody who survives going around Cape Horn in a violent typhoon, he survives one of the worst scurvy outbreaks ever recorded. He survives the shipwreck and then survives one of the longest castaway voyages. And yet, unlike so many others, he cannot tell his story. He is kidnapped and sold into slavery. I could find no record of what had happened to him. The absence of John Duck’s story underscores how many chapters of history can never be told. I was as haunted in many ways by the gaps in the story — by the John Ducks. What his story drove home to me was that the most sinister crimes and worse racial injustices have been largely excised from the American consciousness.

The Wager is clearly about the cost of empire and yet most of these people on the ship are just trying to stay alive or make some money, and remain seemingly unaware that they are in the service of an imperialist nation. They are completely unconscious. When you read their narratives in the journals, these people are either dreaming about heroism or rising in the ranks of the military, or coming back with riches or simply trying simply to survive to get back to their families. And many of them are victims of this system.

Some are just folks off the street who get kidnapped or press-ganged into service in the navy. Many of these people didn’t even want to go on the damn voyage. They’re forced onto the ship. And I do think the narrative reveals how empires survive by having so many citizens, consciously or not, who are complicit. So many of these people are complicit in a system that is also victimizing them.

You’ve written about explorers who get lost in the Amazon and someone trying to cross-country ski across Antarctica . Why are you drawn to extreme stories? Those circumstances are like these little laboratories that test the human condition. They end up revealing something, the kind of secret nature, the hidden nature of us, the good and the bad. And you can really see it play out. So I think they’re revelatory sorts of tales. Like in the Wager , you see these selfless acts, and then the same person, moments later, will commit a shocking act of brutality.

It all goes south very fast for the men of the Wager. They descend into a Hobbesian state of nature. They start off with the imperial notion that Western civilization is somehow superior, yet they descend into warring factions and there are mutinies and murders, and a few even succumb to cannibalism. Which is probably why the British Empire wants the story to go away. They don’t want to admit that British officers didn’t behave like gentlemen, they behave like brutes.

Trump Forced to See Mean Memes About Him Shared by Prospective Jurors

Supreme court justices may do trump and jan. 6 rioters a solid, cher's son argues she's 'unfit to serve' as his conservator, o.j. simpson executor clarifies stance on goldmans receiving money from estate.

OK, so, you’ve written about the Amazon, the shipwreck of the Wager, and a deadly trek across Antarctica on skis. How would David Grann do in any of these experiences? I’m like a little nerdy guy. I’m basically half-blind, bald, out of shape — at this point, sadly, an older gentleman. The idea for me to go exploring is the most preposterous thing in the world.

Scientology Boss David Miscavige Gets Judge Knocked Off Sex Assault Lawsuit

- Courts and Crime

- By Nancy Dillon

Jerrod Carmichael Is Sorry for Criticizing Dave Chappelle's Trans Jokes — to the Press

- By Jon Blistein

How the United States Arms the Mexican Cartels

- By Ieva Jusionyte

Musk's Loyal Tesla Investors Deny Panic Over Layoffs and Stock Dive

- Crumple Zone

- By Miles Klee

America's First Olympic Breakdancer Is Ready to Take Gold

- By Brandon Sneed

Most Popular

Ryan gosling and kate mckinnon's 'close encounter' sketch sends 'snl' cold open into hysterics, keanu reeves joins 'sonic 3' as shadow, michael douglas is the latest actor to make controversial remarks about intimacy coordinators, masters 2024 prize money pegged at $20m, up $2m from prior year, you might also like, jimmy buffett tribute at hollywood bowl brings together paul mccartney, eagles, snoop dogg, harrison ford, brandi carlile, jane fonda and scores of stars, as q1 revenue falls, lvmh plays the waiting game, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, inside that epic ‘shogun’ episode 9 moment: ‘the best scene of the season’, caitlin clark smashes another tv record as wnba draft draws 2.45m.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Verify it's you

Please log in.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny, and Murder

By David Grann

Typhoons. Scurvy. Shipwreck. Mutiny. Cannibalism. A war over the truth and who gets to write history. All of these elements converge in David Grann’s upcoming book, “ The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder .” It tells the extraordinary saga of the officers and crew of the Wager, a British naval warship that wrecked off the Chilean coast of Patagonia, in 1741. The men, marooned on a desolate island, descended into murderous anarchy. Years later, several survivors made it back to England, where, facing a court-martial and desperate to save their own lives, they gave wildly conflicting versions of what had happened. They each attempted to shade a scandalous truth—to erase history. As did the British Empire.

In 2016, Grann, a staff writer at the magazine and the author of “ Killers of the Flower Moon ” and “ The Lost City of Z ,” stumbled across an eyewitness account of the voyage by John Byron, who had been a sixteen-year-old midshipman on the Wager when the journey began. (Byron was the grandfather of the poet Lord Byron, who drew, in “ Don Juan ,” on what he referred to as “my grand-dad’s ‘Narrative.’ ”) Grann set out to reconstruct what really took place, and spent more than half a decade combing through the archival debris: the washed-out logbooks, the moldering correspondence, the partly truthful journals, the surviving records from the court-martial. To better understand what the castaways had endured on the island, which is situated in the Gulf of Sorrows—or, as some prefer to call it, the Gulf of Pain—he travelled there in a small, wood-heated boat.

In this excerpt, of the book’s prologue and first chapter, Grann introduces David Cheap, a burly, tempestuous British naval lieutenant. During the chaotic voyage, he was promoted to captain of the Wager and, at long last, fulfilled his dream of becoming a lord of the sea—that is, until the wreck.

The only impartial witness was the sun. For days, it watched as the strange object heaved up and down in the ocean, tossed mercilessly by the wind and the waves. Once or twice, the vessel nearly smashed into a reef, which might have ended our story. Yet somehow—whether through destiny, as some would later proclaim, or dumb luck—it drifted into an inlet, off the southeastern coast of Brazil, where several inhabitants laid eyes upon it.

More than fifty feet long and ten feet wide, it was a boat of some sort—though it looked as if it had been patched together from scraps of wood and cloth and then battered into oblivion. Its sails were shredded, its boom shattered. Seawater seeped through the hull, and a stench emanated from within. The bystanders, edging closer, heard unnerving sounds: thirty men were crammed on board, their bodies wasted almost to the bone. Their clothes had largely disintegrated. Their faces were enveloped in hair, tangled and salted like seaweed.

Some were so weak they could not even stand. One soon gave out his last breath and died. But a figure who appeared to be in charge rose with an extraordinary exertion of will and announced that they were castaways from His Majesty’s Ship the Wager, a British man-of-war.

When the news reached England, it was greeted with disbelief. In September, 1740, during an imperial conflict with Spain, the Wager, carrying some two hundred and fifty officers and crew, had embarked from Portsmouth in a squadron on a secret mission: to capture a treasure-filled Spanish galleon known as “the prize of all the oceans.” Near Cape Horn, at the tip of South America, the squadron had been engulfed by a hurricane, and the Wager was believed to have sunk with all its souls. But, two hundred and eighty-three days after the ship had last been reported seen, these men miraculously emerged in Brazil.

They had been shipwrecked on a desolate island off the coast of Patagonia. Most of the officers and crew had perished, but eighty-one survivors had set out in a makeshift boat lashed together partly from the wreckage of the Wager. Packed so tightly on board that they could barely move, they travelled through menacing gales and tidal waves, through ice storms and earthquakes. More than fifty men died during the arduous journey, and, by the time the few remnants reached Brazil three and a half months later, they had traversed nearly three thousand miles—one of the longest castaway voyages ever recorded. They were hailed for their ingenuity and bravery. As the leader of the party noted, it was hard to believe that “human nature could possibly support the miseries that we have endured.”

Six months later, another boat washed ashore, this one landing in a blizzard off the southwestern coast of Chile. It was even smaller—a wooden dugout propelled by a sail stitched from the rags of blankets. On board were three additional survivors, and their condition was even more frightful. They were half naked and emaciated; insects swarmed over their bodies, nibbling on what remained of their flesh. One man was so delirious that he had “quite lost himself,” as a companion put it, “not recollecting our names . . . or even his own.”

After these men recovered and returned to England, they levelled a shocking allegation against their companions who had surfaced in Brazil. They were not heroes—they were mutineers. In the controversy that followed, with charges and countercharges from both sides, it became clear that while stranded on the island the Wager’s officers and crew had struggled to persevere in the most extreme circumstances. Faced with starvation and freezing temperatures, they built an outpost and tried to re-create naval order. But, as their situation deteriorated, the Wager’s officers and crew—those supposed apostles of the Enlightenment—descended into a Hobbesian state of depravity. There were warring factions and marauders and abandonments and murders. A few of the men succumbed to cannibalism.

Back in England, the principal figures from each group, along with their allies, were now summoned by the Admiralty to face a court-martial. The trial threatened to expose the secret nature not only of those charged but also of an empire whose self-professed mission was spreading civilization.

Several of the accused published sensational—and wildly conflicting—accounts of what one of them called the “dark and intricate” affair. The philosophers Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu were influenced by reports of the expedition, and so, later, were Charles Darwin and two of the great novelists of the sea, Herman Melville and Patrick O’Brian. The suspects’ main aim was to sway the Admiralty and the public. A survivor from one party composed what he described as a “faithful narrative,” insisting, “I have been scrupulously careful not to insert one word of untruth: for falsities of any kind would be highly absurd in a work designed to rescue the author’s character.” The leader of the other side claimed, in his own chronicle, that his enemies had furnished an “imperfect narrative” and “blackened us with the greatest calumnies.” He vowed, “We stand or fall by the truth; if truth will not support us, nothing can.”

We all impose some coherence—some meaning—on the chaotic events of our existence. We rummage through the raw images of our memories, selecting, burnishing, erasing. We emerge as the heroes of our stories, which allows us to live with what we have done—or haven’t done.

But these men believed that their very lives depended on the stories they told. If they failed to provide a convincing tale, they could be secured to a ship’s yardarm and hanged.

Chapter 1: The First Lieutenant

Each man in the squadron carried, along with a sea chest, his own burdensome story. Perhaps it was of a scorned love, or a secret prison conviction, or a pregnant wife left onshore weeping. Perhaps it was a hunger for fame and fortune, or a dread of death. David Cheap, the first lieutenant of the Centurion, the squadron’s flagship, was no different. A burly Scotsman in his early forties, with a protracted nose and intense eyes, he was in flight—from squabbles with his brother over their inheritance, from creditors chasing him, from debts that made it impossible for him to find a suitable bride. Onshore, Cheap seemed doomed, unable to navigate past life’s unexpected shoals. Yet, as he perched on the quarterdeck of a British man-of-war, cruising the vast oceans with a cocked hat and spyglass, he brimmed with confidence—even, some would say, a touch of haughtiness. The wooden world of a ship—a world bound by the Navy’s rigid regulations and the laws of the sea and, most of all, by the hardened fellowship of men—had provided him a refuge. Suddenly, he felt a crystalline order, a clarity of purpose. And Cheap’s newest posting, despite the innumerable risks that it carried, from plagues and drowning to enemy cannon fire, offered what he longed for: a chance to finally claim a wealthy prize and rise to captain his own ship.

The problem was that he could not get away from the damned land. He was trapped—cursed, really—at the dockyard in Portsmouth, along the English Channel, struggling with feverish futility to get the Centurion fitted out and ready to sail. Its massive wooden hull, a hundred and forty-four feet long and forty feet wide, was moored at a slip. Carpenters, caulkers, riggers, and joiners combed over its decks like rats (which were also plentiful). A cacophony of hammers and saws. The cobblestone streets past the shipyard were congested with rattling wheelbarrows and horse-drawn wagons, with porters, peddlers, pickpockets, sailors, and prostitutes. Periodically, a boatswain blew a chilling whistle, and crewmen stumbled from ale shops, parting from old or new sweethearts, hurrying to their departing ships in order to avoid their officers’ lashes.

It was January, 1740, and the British Empire was racing to mobilize for war against its imperial rival Spain. And, in a move that had suddenly raised Cheap’s prospects, the captain under whom he served on the Centurion, George Anson, had been plucked by the Admiralty to be a commodore and lead the squadron of five warships against the Spanish. The promotion was unexpected. As the son of an obscure country squire, Anson did not wield the level of patronage, the grease—or “interest,” as it was more politely called—that propelled many officers up the pole, along with their men. Anson, then forty-two, had joined the Navy at the age of fourteen, and served for nearly three decades without leading a major military campaign or snaring a lucrative prize.

Tall, with a long face and a high forehead, he had a remoteness about him. His blue eyes were inscrutable, and outside the company of a few trusted friends he rarely opened his mouth. One statesman, after meeting with him, noted, “Anson, as usual, said little.” Anson corresponded even more sparingly, as if he doubted the ability of words to convey what he saw or felt. “He loved reading little, and writing, or dictating his own letters less, and that seeming negligence . . . drew upon him the ill will of many,” a relative wrote. A diplomat later quipped that Anson was so unknowing about the world that he’d been “round it, but never in it.”

Nevertheless, the Admiralty had recognized in Anson what Cheap had also seen in him in the two years since he’d joined the Centurion’s crew: a formidable seaman. Anson had a mastery of the wooden world and, equally important, a mastery of himself—he remained cool and steady under duress. His relative noted, “He had high notions of sincerity and honor and practiced them without deviation.” In addition to Cheap, he had attracted a coterie of talented junior officers and protégés, all vying for his favor. One later informed Anson that he was more obliged to him than to his own father and would do anything to “act up to the good opinion you are pleased to have of me.” If Anson succeeded in his new role as the commodore of the squadron, he would be in a position to anoint any captain he wanted. And Cheap, who’d initially served as Anson’s second lieutenant, was now his right-hand man.

Like Anson, Cheap had spent much of his life at sea, a bruising existence that he’d at first hoped to escape. As Samuel Johnson once observed, “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned.” Cheap’s father had possessed a large estate in Fife, Scotland, and the sort of title—the second Laird of Rossie—that evoked nobility even if it did not quite confer it. His motto, emblazoned on the family’s crest, was Ditat virtus: “Virtue enriches.” He had seven children with his first wife, and, after she died, he had six more with his second, among them David.

In 1705, the year that David celebrated his eighth birthday, his father stepped out to fetch some goat’s milk and dropped dead. As was the custom, it was the oldest male heir—David’s half brother James—who inherited the bulk of the estate. And so David was buffeted by forces beyond his control, in a world divided between first sons and younger sons, between haves and have-nots. Compounding the upheaval, James, now ensconced as the third Laird of Rossie, frequently neglected to pay the allowance that had been bequeathed to his half brothers and half sister: some people’s blood was apparently thicker than others’. Driven to find work, David apprenticed to a merchant, but his debts mounted. So, in 1714, the year he turned seventeen, he ran off to sea, a decision that was evidently welcomed by his family—as his guardian wrote to his older brother, “The sooner he goes off it will be better for you and me.”

After these setbacks, Cheap seemed only more consumed by his festering dreams, more determined to bend what he called an “unhappy fate.” On his own, on an ocean distant from the world he knew, he might prove himself in elemental struggles—braving typhoons, outduelling enemy ships, rescuing his companions from calamities.

But, though Cheap had chased a few pirates—including the one-handed Irishman Henry Johnson, who fired his gun by resting the barrel on his stump—these earlier voyages had proved largely uneventful. He’d been sent to patrol the West Indies, generally considered the worst assignment in the Navy because of the spectre of disease. The Saffron Scourge. The Bloody Flux. The Breakbone Fever. The Blue Death.

But Cheap had endured. Wasn’t there something to be said for that? Moreover, he’d earned the trust of Anson and worked his way up to first lieutenant. No doubt it helped that they shared a disdain for reckless banter, or what Cheap deemed a “vaporing manner.” A Scottish minister who later became close to Cheap noted that Anson had employed him because he was “a man of sense and knowledge.” Cheap, the once forlorn debtor, was but one rung from his coveted captaincy. And, with the war with Spain having broken out, he was about to head into full-fledged battle for the first time.

The conflict was the result of the endless jockeying among the European powers to expand their empires. They each vied to conquer or control ever larger swaths of the earth, so that they could exploit and monopolize other peoples’ valuable natural resources and trade markets. In the process, they subjugated and destroyed innumerable Indigenous populations, justifying their ruthless self-interest—including a reliance on the ever-expanding Atlantic slave trade—by claiming that they were somehow spreading “civilization” to the benighted realms of the earth. Spain had long been the dominant empire in Latin America, but Great Britain, which already possessed colonies along the American Eastern Seaboard, was now in the ascendant—and determined to break its rival’s hold.

Then, in 1738, Robert Jenkins, a British merchant captain, was summoned to appear in Parliament, where he reportedly claimed that a Spanish officer had stormed his brig in the Caribbean and, accusing him of smuggling sugar from Spain’s colonies, cut off his left ear. Jenkins reputedly displayed his severed appendage, pickled in a jar, and pledged “my cause to my country.” The incident further ignited the passions of Parliament and pamphleteers, leading people to cry for blood—an ear for an ear—and a good deal of booty as well. The conflict became known as the War of Jenkins’s Ear.

British authorities soon devised a plan to launch an attack on a hub of Spain’s colonial wealth, Cartagena. A South American city on the Caribbean, it was where much of the silver extracted from Peruvian mines was loaded into armed convoys to be shipped to Spain. The British offensive—involving a fleet of a hundred and eighty-six ships, led by Admiral Edward Vernon—would be the largest amphibious assault in history. But there was also another, much smaller operation, the one assigned to Commodore Anson.

With five warships and a scouting sloop, he and some two thousand men would sail across the Atlantic and round Cape Horn, “taking, sinking, burning, or otherwise destroying” enemy ships and weakening Spanish holdings from the Pacific coast of South America to the Philippines. The British government, in concocting its scheme, wanted to avoid the impression that it was merely sponsoring piracy. Yet the heart of the plan called for an act of outright thievery: to snatch a Spanish galleon loaded with virgin silver and hundreds of thousands of silver coins. Twice a year, Spain sent such a galleon—it was not always the same ship—from Mexico to the Philippines to purchase silks and spices and other Asian commodities, which, in turn, were sold in Europe and the Americas. These exchanges provided crucial links in Spain’s global trading empire.

Cheap and the others ordered to carry out the mission were rarely privy to the agendas of those in power, but they were lured by a tantalizing prospect: a share of the treasure. The Centurion’s twenty-two-year-old chaplain, the Reverend Richard Walter, who later compiled an account of the voyage, described the galleon as “the most desirable prize that was to be met with in any part of the globe.”

If Anson and his men prevailed—“if it shall please God to bless our arms,” as the Admiralty put it—they would continue circling the earth before returning home. The Admiralty had given Anson a code and a cipher to use for his written communication, and an official warned that the mission must be carried out in the “most secret, expeditious manner.” Otherwise, Anson’s squadron might be intercepted and destroyed by a Spanish armada being assembled under the command of Don José Pizarro.

Cheap was facing his longest expedition—he might be gone for three years—and his most perilous. But he saw himself as a knight-errant of the sea in search of “the greatest prize of all the oceans.” And, along the way, he might become a captain yet.

But, if the squadron didn’t embark quickly, Cheap feared, the entire party would be annihilated by a force even more dangerous than the Spanish armada: the violent seas around Cape Horn. Only a few British sailors had successfully made this passage, where winds routinely blow at gale force, waves can climb to nearly a hundred feet, and icebergs lurk in the hollows. Seamen thought that the best chance to survive was during the austral summer, between December and February. The Reverend Walter cited this “essential maxim,” explaining that, during winter, there were not only fiercer seas and freezing temperatures but also fewer hours of daylight in which one could discern the uncharted coastline. All these reasons, he argued, would make navigating around this unknown shore the “most dismaying and terrible” endeavor.

But, since war had been declared, in October, 1739, the Centurion and the other men-of-war in the squadron—including the Gloucester, the Pearl, and the Severn—had been marooned in England, waiting to be repaired and fitted out for the next journey. Cheap watched helplessly as the days ticked by. January, 1740, came and went. Then February and March. It was nearly half a year since the war with Spain had been declared; still, the squadron was not ready to sail.

It should have been an imposing force. Men-of-war were among the most sophisticated machines yet conceived: buoyant wooden castles powered across oceans by wind and sail. Reflecting the dual nature of their creators, they were devised to be both murderous instruments and the homes in which hundreds of sailors lived together as a family. In a lethal, floating chess game, these pieces were deployed around the globe to achieve what Sir Walter Raleigh had envisioned: “Whosoever commands the seas commands the trade of the world; whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world.”

Cheap knew what a cracking ship the Centurion was. Swift and stout, and weighing about a thousand tons, she had, like the other warships in Anson’s squadron, three towering masts with crisscrossing yards—wooden spars from which the sails unfurled. The Centurion could fly as many as eighteen sails at a time. Its hull gleamed with varnish, and painted around the stern in gold relief were Greek mythological figures, including Poseidon. On the bow rode a sixteen-foot wooden carving of a lion, painted bright red. To increase the chances of surviving a barrage of cannonballs, the hull had a double layer of planks, giving it a thickness of more than a foot in places. The ship had several decks, each stacked upon the next, and two of them had rows of cannons on both sides—their menacing black muzzles pointing out of square gunports. Augustus Keppel, a fifteen-year-old midshipman who was one of Anson’s protégés, boasted that other men-of-war had “no chance in the world” against the mighty Centurion.

Yet building, repairing, and fitting out these watercraft was a herculean endeavor even in the best of times, and in a period of war it was chaos. The royal dockyards, which were among the largest manufacturing sites in the world, were overwhelmed with ships—leaking ships, half-constructed ships, ships needing to be loaded and unloaded. Anson’s vessels were laid up on what was known as Rotten Row. As sophisticated as men-of-war were with their sail propulsion and lethal gunnery, they were largely made from simple, perishable materials: hemp, canvas, and, most of all, timber. Constructing a single large warship could require as many as four thousand trees; a hundred acres of forest might be felled.

Most of the wood was hard oak, but it was still susceptible to the pulverizing elements of storm and sea. Teredo navalis —a reddish shipworm, which can grow longer than a foot—ate through hulls. (Columbus lost two ships to these creatures during his fourth voyage to the West Indies.) Termites also bored through decks and masts and cabin doors, as did deathwatch beetles. A species of fungus further devoured a ship’s wooden core. In 1684, Samuel Pepys, a secretary to the Admiralty, was stunned to discover that many new warships under construction were already so rotten that they were “in danger of sinking at their very moorings.”

The average man-of-war was estimated by a leading shipwright to last only fourteen years. And, to survive that long, a ship had to be virtually remade after each extensive voyage, with new masts and sheathing and rigging. Otherwise, it risked disaster. In 1782, while the hundred-and-eighty-foot Royal George—for a time the largest warship in the world—was anchored near Portsmouth, with a full crew on board, water began flooding its hull. It sank. The cause has been disputed, but an investigation blamed the “general state of decay of her timbers.” An estimated nine hundred people drowned.

Cheap learned that an inspection of the Centurion had turned up the usual array of sea wounds. A shipwright reported that the wooden sheathing on its hull was “so much worm eaten” that it had to be taken off and replaced. The foremast, toward the bow, contained a rotten cavity a foot deep, and the sails were, as Anson noted in his log, “much rat eaten.” The squadron’s other four warships faced similar problems. Moreover, each vessel had to be loaded with tons of provisions, including some forty miles of rope, more than fifteen thousand square feet of sails, and a farm’s worth of livestock—chickens, pigs, goats, and cattle. (It could be fiercely difficult to get such animals on board: steers “do not like the water,” a British captain complained.)

Cheap pleaded with the naval administration to finish readying the Centurion. But it was that familiar story of wartime: though much of the country had clamored for battle, the people were unwilling to pay enough for it. And the Navy was strained to a breaking point. Cheap could be volatile, his moods shifting like the winds, and here he was, stuck as a landsman, a pen pusher! He badgered dockyard officials to replace the Centurion’s damaged mast, but they insisted that the cavity could simply be patched. Cheap wrote to the Admiralty decrying this “very strange way of reasoning,” and officials eventually relented. But more time was lost.

And where was that bastard of the fleet, the Wager? Unlike the other men-of-war, it was not born for battle but had been a merchant vessel—a so-called East Indiaman, because it traded in that region. Intended for heavy cargo, it was tubby and unwieldy, a hundred-and-twenty-three-foot eyesore. After the war began, the Navy, needing additional ships, had purchased it from the East India Company for nearly four thousand pounds. Since then, it had been sequestered eighty miles northeast of Portsmouth, at Deptford, a royal dockyard on the Thames, where it was undergoing a metamorphosis: cabins were torn apart, holes cut into the outer walls, and a stairwell obliterated.

The Wager’s captain, Dandy Kidd, surveyed the work being done. Fifty-six years old, and reportedly a descendant of the infamous buccaneer William Kidd, he was an experienced seaman, and a superstitious one—he saw portents lurking in the winds and the waves. Only recently had he obtained what Cheap dreamed of: the command of his own ship. At least from Cheap’s perspective, Kidd had earned his promotion, unlike the captain of the Gloucester, Richard Norris, whose father, Sir John Norris, was a celebrated admiral; Sir John had helped to secure his son a position in the squadron, noting that there would be “both action and good fortune to those who survived.” The Gloucester was the only vessel in the squadron being swiftly repaired, prompting another captain to complain, “I lay three weeks in the dock and not a nail drove, because Sir John Norris’s son must first be served.”

Captain Kidd bore his own story. He’d left behind, at a boarding school, a five-year-old son, also named Dandy, who had no mother to raise him. What would happen to him if his father didn’t survive the voyage? Already Captain Kidd feared the omens. In his log, he wrote that his new ship nearly “tumbled over,” and he warned the Admiralty that she might be a “crank”—a ship that heeled abnormally. To give the hull ballast so the ship wouldn’t capsize, more than four hundred tons of pig iron and gravel stones were lowered through the hatches into the dark, dank, cavernous hold.

The workers toiled through one of England’s coldest winters on record, and, just as the Wager was ready to sail, Cheap learned to his dismay, something extraordinary happened: the Thames froze, shimmering from bank to bank with thick, unbreakable waves of ice. An official at Deptford advised the Admiralty that the Wager was imprisoned until the river melted. Two months passed before she was liberated.

In May, the old East Indiaman finally emerged from the Deptford Dockyard as a man-of-war. The Navy classified warships by their number of cannons, and, with twenty-eight, she was a sixth-rate—the lowest rank. She was christened in honor of Sir Charles Wager, the seventy-four-year-old First Lord of the Admiralty. The ship’s name seemed fitting: weren’t they all gambling with their lives?

As the Wager was piloted down the Thames, drifting with the tides along that central highway of trade, she floated past West Indiamen loaded with sugar and rum from the Caribbean, past East Indiamen with silks and spices from Asia, past blubber hunters returning from the Arctic with whale oil for lanterns and soaps. While the Wager was navigating this traffic, her keel ran aground on a shoal. Imagine being shipwrecked here! But it soon dislodged, and in July the ship arrived at last outside Portsmouth harbor, where Cheap laid eyes upon her. Seamen were merciless oglers of passing ships, pointing out their elegant curves or their hideous flaws. And, though the Wager had assumed the proud look of a man-of-war, she could not completely conceal her former self, and Captain Kidd beseeched the Admiralty, even at this late date, to give the vessel a fresh coat of varnish and paint so that she could shine like the other ships.

By the middle of July, nine bloodless months had gone by for the squadron since the war began. If the ships left promptly, Cheap was confident that they could reach Cape Horn before the end of the austral summer. But the men-of-war were still missing the most important element of all: men.

Because of the length of the voyage and the planned amphibious invasions, each warship in Anson’s squadron was supposed to carry an even greater number of seamen and marines than it was designed for. The Centurion, which typically held four hundred people, was expected to sail with some five hundred, and the Wager would be packed with about two hundred and fifty—nearly double its usual complement.

Cheap had waited and waited for crewmen to arrive. But the Navy had exhausted its supply of volunteers, and Great Britain had no military conscription. Robert Walpole, the country’s first Prime Minister, warned that the dearth of crews had rendered a third of the Navy’s ships unusable. “Oh! seamen, seamen, seamen!” he cried at a meeting.

While Cheap was struggling with other officers to scrounge up sailors for the squadron, he received more unsettling news: those men who had been recruited were falling sick. Their heads throbbed, and their limbs were so sore that they felt as if they’d been pummelled. In severe cases, these symptoms were compounded by diarrhea, vomiting, bursting blood vessels, and fevers reaching as high as a hundred and six degrees. (This led to delirium—“catching at imaginary objects in the air,” as a medical treatise put it.)

Some men succumbed even before they had gone to sea. Cheap counted at least two hundred sick and more than twenty-five dead on the Centurion alone. He had brought his young nephew Henry to apprentice on the expedition . . . and what if he perished? Even Cheap, who was so indomitable, was suffering from what he called a “very indifferent state of health.”

It was a devastating epidemic of “ship’s fever,” now known as typhus. No one then understood that the disease was a bacterial infection, transmitted by lice and other vermin. As boats transported unwashed recruits crammed together in filth, the men became lethal vectors, deadlier than a cascade of cannonballs.

Anson instructed Cheap to have the sick rushed to a makeshift hospital in Gosport, near Portsmouth, in the hope that they would recover in time for the voyage. The squadron still desperately needed men. But, as the hospital became overcrowded, most of the sick had to be lodged in surrounding taverns, which offered more liquor than medicine, and where three patients sometimes had to squeeze into a single cot. An admiral noted, “In this miserable way, they die very fast.”

After peaceful efforts to man the fleets failed, the Navy resorted to what a secretary of the Admiralty called a “more violent” strategy. Armed gangs were dispatched to press seafaring men into service—in effect, kidnapping them. The gangs roamed cities and towns, grabbing anyone who betrayed the telltale signs of a mariner: the familiar checkered shirt and wide-kneed trousers and round hat; the fingers smeared with tar, which was used to make virtually everything on a ship more water-resistant and durable. (Seamen were known as tars.) Local authorities were ordered to “seize all straggling seamen, watermen, bargemen, fishermen and lightermen.”

A seaman later described walking in London and having a stranger tap him on the shoulder and demand, “What ship?” The seaman denied that he was a sailor, but his tar-stained fingertips betrayed him. The stranger blew his whistle; in an instant, a posse appeared. “I was in the hands of six or eight ruffians whom I soon found to be a press gang,” the seaman wrote. “They dragged me hurriedly through several streets, amid bitter execrations bestowed on them from passersby and expressions of sympathy directed towards me.”

Press-gangs headed out in boats as well, scouring the horizon for incoming merchant ships—the most fertile hunting ground. Often, men seized were returning from distant voyages and hadn’t seen their families for years; given the risks of a subsequent long voyage during war, they might never see them again.

Cheap became close to a young midshipman on the Centurion named John Campbell, who had been pressed while serving on a merchant ship. A gang had invaded his vessel, and when he saw them hauling away an older man in tears he stepped forward and offered himself up in his place. The head of the press-gang remarked, “I would rather have a lad of spirit than a blubbering man.”

Anson was said to have been so struck by Campbell’s gallantry that he’d made him a midshipman. Most sailors, though, went to extraordinary lengths to evade the “body snatchers”—hiding in cramped holds, listing themselves as dead in muster books, and abandoning merchant ships before reaching a major port. When a press-gang surrounded a church in London, in 1755, in pursuit of a seaman inside, he managed, according to a newspaper report, to slip away disguised in “an old gentlewoman’s long cloak, hood and bonnet.”

Sailors who got snatched up were transported in the holds of small ships known as tenders, which resembled floating jails, with gratings bolted over the hatchways and marines standing guard with muskets and bayonets. “In this place we spent the day and following night huddled together, for there was not room to sit or stand separate,” one seaman recalled. “Indeed, we were in a pitiable plight, for numbers of them were sea-sick, some retching, others were smoking, whilst many were so overcome by the stench, that they fainted for want of air.”

Family members, upon learning that a relative—a son, or a brother, or a husband, or a father—had been apprehended, would often rush to where the tenders were departing, hoping to glimpse their loved one. Samuel Pepys describes, in his diary, a scene of pressed sailors’ wives gathered on a wharf near the Tower of London : “In my life, I never did see such a natural expression of passion as I did here in some women’s bewailing themselves, and running to every parcel of men that were brought, one after another, to look for their husbands, and wept over every vessel that went off, thinking they might be there, and looking after the ship as far as ever they could by moonlight, that it grieved me to the heart to hear them.”

Anson’s squadron received scores of pressed men. Cheap processed at least sixty-five for the Centurion; however distasteful he might have found the press, he needed every sailor he could get. Yet the unwilling recruits deserted at the first opportunity, as did volunteers who were having misgivings. In a single day, thirty men vanished from the Severn. Of the sick men sent to Gosport, countless took advantage of lax security to flee—or, as one admiral put it, “go off as soon as they can crawl.” Altogether, more than two hundred and forty men absconded from the squadron, including the Gloucester’s chaplain. When Captain Kidd dispatched a press-gang to find new recruits for the Wager, six members of the gang itself deserted.

Anson ordered the squadron to moor far enough outside Portsmouth harbor that swimming to freedom was impossible—a frequent tactic that led one trapped seaman to write to his wife, “I would give all I had if it was a hundred guineas if I could get on shore. I only lays on the deck every night. There is no hopes of my getting to you . . . . do the best you can for the children and God prosper you and them till I come back.”

Cheap, who believed that a good sailor must possess “honour, courage . . . steadiness,” was undoubtedly appalled by the quality of the recruits who lingered. It was common for local authorities, knowing the unpopularity of the press, to dump their undesirables. But these conscripts were wretched, and the volunteers were little better. An admiral described one bunch of recruits as being “full of the pox, itch, lame, King’s evil, and all other distempers, from the hospitals at London, and will serve only to breed an infection in the ships; for the rest, most of them are thieves, house breakers, Newgate [Prison] birds, and the very filth of London.” He concluded, “In all the former wars I never saw a parcel of turned over men half so bad, in short they are so very bad, that I don’t know how to describe it.”

To at least partly address the shortage of men, the government sent to Anson’s squadron a hundred and forty-three marines, who in those days were a branch of the Army, with their own officers. The marines were supposed to help with land invasions and also lend a hand at sea. Yet they were such raw recruits that they had never set foot on a ship and didn’t even know how to fire a weapon. The Admiralty admitted that they were “useless.” In desperation, the Navy took the extreme step of rounding up for Anson’s squadron five hundred invalid soldiers from the Royal Hospital, in Chelsea, a pensioner’s home established in the seventeenth century for veterans who were “old, lame, or infirm in ye service of the Crowne.” Many were in their sixties and seventies, and they were rheumatic, hard of hearing, partly blind, suffering from convulsions, or missing an assortment of limbs. Given their ages and debilities, these soldiers had been deemed unfit for active service. The Reverend Walter described them as the “most decrepit and miserable objects that could be collected.”

As these invalids made their way to Portsmouth, nearly half slipped away, including one who hobbled off on a wooden leg. “All those who had limbs and strength to walk out of Portsmouth deserted,” the Reverend Walter noted. Anson pleaded with the Admiralty to replace what his chaplain called “this aged and diseased detachment.” No recruits were available, though, and after Anson dismissed some of the most infirm men his superiors ordered them back on board.

Cheap watched the incoming invalids, many of them so weak that they had to be lifted onto the ships on stretchers. Their panicked faces betrayed what everyone secretly knew: they were sailing to their deaths. As the Reverend Walter acknowledged, “They would in all probability uselessly perish by lingering and painful diseases; and this, too, after they had spent the activity and strength of their youth in their country’s service.”

On August 23, 1740, after nearly a year of delays, the battle before the battle was over, with “everything being in readiness to proceed on the voyage,” as an officer of the Centurion wrote in his journal. Anson ordered Cheap to fire one of the guns. It was the signal for the squadron to unmoor, and at the sound of the blast the entire force—the five men-of-war and an eighty-four-foot scouting sloop, the Trial, as well as two small cargo ships, the Anna and the Industry, which would accompany them partway—stirred to life. Officers emerged from quarters; boatswains piped their whistles and cried, “All hands! All hands!”; crewmen raced about, extinguishing candles, lashing hammocks, and loosening sails. Everything around Cheap—Anson’s eyes and ears—seemed to be in motion, and then the ships began to move, too. Farewell to the debt collectors, the invidious bureaucrats, the endless frustrations. Farewell to all of it.

As the convoy made its way down the English Channel toward the Atlantic, it was surrounded by other departing ships, jockeying for wind and space. Several vessels collided, terrifying the uninitiated landsmen on board. And then the wind, as fickle as the gods, abruptly shifted in front of them. Anson’s squadron, unable to bear that close to the wind, was forced to return to its starting point. Twice more it embarked, only to retreat. On September 5th, the London Daily Post reported that the fleet was still “waiting for a favourable wind.” After all the trials and tribulations—Cheap’s trials and tribulations—the squadron seemed condemned to remain in this place.

Yet, on September 18th, as the sun was going down, the seamen caught a propitious breeze. Even some of the recalcitrant recruits were relieved to be finally under way. At least they would have tasks to distract them, and now they could pursue that serpentine temptation, the galleon. “The men were elevated with hopes of growing immensely rich,” a seaman on the Wager wrote in his journal, “and in a few years of returning to Old England loaded with the wealth of their enemies.”

Cheap assumed his commanding perch on the quarterdeck—an elevated platform by the stern that served as the officers’ bridge and housed the steering wheel and a compass. He inhaled the salted air and listened to the splendid symphony around him: the rocking of the hull, the snapping of the halyards, the splashing of waves against the prow. The ships glided in elegant formation, with the Centurion leading the way, her sails spread like wings.

After a while, Anson ordered a red pendant, signifying his rank as commodore of the fleet, to be hoisted on the Centurion’s mainmast.

The other captains fired their guns thirteen times each in salute—a thunderous clapping, a trail of smoke fading in the sky. The ships emerged from the Channel, born into the world anew, and Cheap, ever vigilant, saw the shore receding until, at last, he was surrounded by the deep blue sea.

This is drawn from “ The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder . ”

New Yorker Favorites

Why facts don’t change our minds .

The tricks rich people use to avoid taxes .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

How did polyamory get so popular ?

The ghostwriter who regrets working for Donald Trump .

Snoozers are, in fact, losers .

Fiction by Jamaica Kincaid: “Girl”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By James Wood

By Elizabeth Kolbert

By Adam Gopnik

By Graciela Mochkofsky

October Book Review | 'The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder'

High seas adventure and intrigue abound in the true story of the castaways of a British war vessel in 1741. This month’s book review covers “The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder” by David Grann.

The colonial Navies of England and Spain were plundering and fighting halfway across the world in the mid-18 th century. England launched a squadron of five ships including one named The Wager in 1741. Their mission was to attack a Spanish galleon off the coast of Patagonia and capture the silver, gold, and porcelain that Spain had pirated.

Over 250 men set off on The Wager’s ambitious voyage. All was not fun and swagger, however. The Admiralty’s officers had the most to gain from the bounty. The rest of the crew ranged from those forced into service to outlaws and others with dim prospects at home in England. The ships had dwindling provisions, and the crew endured rough seas, sickness, famine and despair. Most perilous was navigating the dreaded Drakes Passage around Cape Horn at the southern tip of the South American continent.

The Wager became separated from the other ships and shipwrecked along the western coast of Patagonia. What ensued was a wrenching experience of survival and mutiny against the ship’s captain. A gunner and a carpenter, low in the Navy’s hierarchy, led a rebellion of survivors who set off in a small makeshift vessel to return to England. So began their harrowing voyage east through the Strait of Magellan. Thirty made it as far as Brazil.

“The Wager” is a compilation of perspectives from various personal accounts of the voyage. Author David Grann, author of the celebrated, “Killers of the Flower Moon” researched the history of the journey in detail from ship logbooks, journals, correspondence, and newspapers. The product is one gripping story of endurance, suspense, deceit, and the testing of loyalty under extreme conditions. Ultimately, the surviving mutineers had one of their greatest challenges: surviving the English Navy’s system of court-martial.

This book draws you into 1741 high seas drama in the first few pages and never lets you go. David Grann has earned another winner on the bestseller list.

“The Wager” is available from the Park City and Summit County libraries.

As Scorsese preps his ‘Flower Moon,’ David Grann’s new book takes to the high seas

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder

By David Grann Doubleday: 352 pages, $30 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org , whose fees support independent bookstores.

What is it about sea stories? Great writers in the tradition of Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad and Patrick O’Brian have used the self-contained world of a ship and its crew to tell stories of fear, greed and rebellion. A shipboard drama, whether it’s a mutiny, a close-quarters battle or a desperate fight to survive the furious elements, shares in common with the locked-room mystery a cast of characters with warring motives and nowhere to go.

New Yorker writer David Grann knows a good story when he sees one; his most recent book, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” about a series of murders on the Osage Indian reservation in the early 1920s, went into multiple printings, and the movie version directed by Martin Scorsese is awaiting theatrical release. In “ The Wager : A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder,” he has found not just a good but a great story, fraught with duplicity, terror and occasional heroism.

With ‘Lost City of Z’ and ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ David Grann is a hot literary property

David Grann is what you might call a writer’s writer.

April 18, 2017

The story of “The Wager” begins in 1740. Britain was at war with Spain in a brutal struggle to claim uncharted territory. It was colonialism at its most naked and avaricious, and the battles were largely fought at sea. The Wager was one of eight ships in a squadron that launched from Portsmouth, England, and headed to South America, its goal to capture a Spanish galleon loaded with treasure — a prize that would enrich both the crew and the English government.

The Wager was a small ship, tasked with carrying trade goods, small weapons, gunpowder and the squadron’s supply of rum (the analogy of the “powder keg” unavoidably comes to mind). The crew was a combustible mix of regular sailors, marines and impressed crewmen — impressment being a kind of slavery wherein men were kidnapped and forced to serve for an indefinite period.

Five hundred invalids from the Royal Hospital in Chelsea, many in their 60s and 70s, were ordered to fill out the ranks. As old as 80 and as young as 6, the Wager crew “had been thrown together as if they were subjects in a whimsical experiment to test the limits of human sociability,” Grann writes.

That is putting it mildly. The venture seemed doomed from the start. The squadron immediately ran into trouble when typhus and then scurvy , a grotesque disease of vitamin C deficiency, struck down the majority of the crew. After another ship’s commander died, the Wager’s capable captain was transferred to replace him, and David Cheap, an untested officer who had never been in charge of a ship, was named captain of the Wager’s crew.

Entertainment & Arts

‘The Lost City of Z’ by David Grann

A fascinating account of retracing the Amazon journey of vanished explorer Percy Fawcett, thought to have inspired the creation of Indiana Jones.

Feb. 15, 2009

As the squadron approached the tip of South America, the weather worsened; the other ships in the squadron began to turn back. But Cheap, who had just grasped the prize of command over the ship, wouldn’t consider it, and ordered the Wager’s crew to sail into some of the wildest seas and worst weather on Earth.

Many writers have tried to convey just how terrifying the waters around South America’s Cape Horn were in the days of wooden ships and uncertain navigation, as boats battled wild winds, freezing mists and 90-foot waves against a surreal backdrop. One writer was succinct about this Mordor-like terrain: “a proper nursery for desperation.” All this before the Wager passed into Cape Horn, where gales reached 200 miles per hour and subzero temperatures coated the ship with a carapace of ice.

One trick Grann pulls off — again and again — is not showing his hand, and this review honors that accomplishment by not revealing the details of what happens next. Suffice it to say that the Wager and what was left of its crew ran onto the rocks of an exceedingly bleak island off the south coast of Chile.

Given the documentation Grann works with, the reader can intuit that not everyone is going to die (though many do). But as Cheap loses control of his desperate men, starvation, mutiny and murder ensue. British bad behavior scares off a tribe of Indigenous rescuers. And the escape attempts of those who try to make it off the island are so brutal, hair-raising and implausible, the reader is left wondering just what makes some human beings so determined to survive.

Another Grann specialty is on full display — creating a cast of indelible characters from the dustiest of sources: 18th century ship’s logs, surgeons’ textbooks, court-martial proceedings. What a fascinating, conflicted lot they are. Cheap, whose driving desire to prove himself completely extinguishes his common sense. John Bulkeley, the Wager’s gunner, a weapons expert and “instinctive leader” whose Bible-inspired narrative gifts would impel him to write an indelible account of events. “Bulkeley relished recording what he saw,” Grann writes. “It gave him a voice, even if no one but him would ever hear it.”

Then there was Midshipman Jack Byron, 16 when the Wager set sail, whose own account would inspire verse by his renegade grandson Lord Byron on the subject. In his poem “Don Juan,” Byron would memorialize the low moment when starving crewmen killed and ate his grandfather’s dog: What could they do? And hunger’s rage grew wild:/So Juan’s spaniel, spite of his entreating, Was kill’d, and portion’d out for present eating.”